Abstract

Objective

Maternal presence in the Neonatal Intensive Care (NICU) supports infant and maternal health, yet mothers face visitation challenges. Based on intersectionality theory, we hypothesized that mothers of Black infants with lower socioeconomic status (SES) living further from the hospital would demonstrate the lowest rates of maternal presence.

Study design

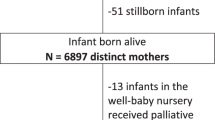

We extracted infant race, Medicaid status, and maternal home address from 238 infant medical charts. The primary outcome was rate of maternal presence. Generalized linear modeling and binomial regression were employed for analysis.

Results

Medicaid status was the strongest single predictor of lower rates of maternal presence. Having lower SES was associated with lower rates of maternal presence in mothers of white infants, and living at a distance from the hospital was associated with lower maternal presence in mothers of higher SES.

Conclusions

Interventions to support maternal presence in the NICU should address resource-related challenges experienced by mothers of lower SES.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

De-identified dataset may be made available upon request to authors.

References

March of Dimes. 2019 March of Dimes Report Card. March of DImes. 2019. Accessed August 22, 2020. https://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/US_REPORTCARD_FINAL.pdf

Trumello C, Candelori C, Cofini M, et al. Mothers’ depression, anxiety, and mental representations after preterm birth: A study during the infant’s hospitalization in a neonatal intensive care unit. Front Public Health. 2018;6:359 https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2018.00359

Ionio C, Colombo C, Brazzoduro V, et al. Mothers and fathers in NICU: the impact of preterm birth on parental distress. Eur J Psychol. 2016;12:604–21. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v12i4.1093

Zelkowitz P, Papageorgiou A, Bardin C, Wang T. Persistent maternal anxiety affects the interaction between mothers and their very low birthweight children at 24 months. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:51–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2008.06.010

Nist MD, Spurlock EJ, Pickler RH. Barriers and facilitators of parent presence in the neonatal intensive care unit. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2024;49:137–44. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMC.0000000000001000

McCarty DB, Letzkus L, Attridge E, Dusing SC. Efficacy of therapist supported interventions from the neonatal intensive care unit to home: a meta-review of systematic reviews. Clin Perinatol. 2023;50:157–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clp.2022.10.004

Socioeconomic Factors | CDC. Accessed May 31, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/health_equity/socioeconomic.htm

Greene MM, Rossman B, Patra K, Kratovil A, Khan S, Meier PP. Maternal psychological distress and visitation to the neonatal intensive care unit. Acta Paediatr. 2015;104:e306–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12975

Head Zauche L, Zauche MS, Dunlop AL, Williams BL. Predictors of parental presence in the neonatal intensive care unit. Adv Neonatal Care. 2020;20:251–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANC.0000000000000687

Thiele K, Buckman C, Naik TK, Tumin D, Kohler JA. Ronald McDonald House accommodation and parental presence in the neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2021;41:2570–2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01115-5

Whitehill L, Smith J, Colditz G, Le T, Kellner P, Pineda R. Socio-demographic factors related to parent engagement in the NICU and the impact of the SENSE program. Early Hum Dev. 2021;163:105486 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2021.105486

Caldwell JT, Ford CL, Wallace SP, Wang MC, Takahashi LM. Intersection of living in a rural versus urban area and race/ethnicity in explaining access to health care in the united states. Am J Public Health. 2016;106:1463–9. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2016.303212

Makkar A, McCoy M, Hallford G, Escobedo M, Szyld E. A hybrid form of telemedicine: a unique way to extend intensive care service to neonates in medically underserved areas. Telemed J E Health. 2018;24:717–21. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2017.0155

Pineda R, Bender J, Hall B, Shabosky L, Annecca A, Smith J. Parent participation in the neonatal intensive care unit: Predictors and relationships to neurobehavior and developmental outcomes. Early Hum Dev. 2018;117:32–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2017.12.008

Jacobs EA, Rolle I, Ferrans CE, Whitaker EE, Warnecke RB. Understanding African Americans’ views of the trustworthiness of physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:642–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00485.x

Wiltshire J, Allison JJ, Brown R, Elder K. African American women perceptions of physician trustworthiness: a factorial survey analysis of physician race, gender and age. AMS Public Health. 2018;5:122–34. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2018.2.122

Hendricks-Muñoz KD, Li Y, Kim YS, Prendergast CC, Mayers R, Louie M. Maternal and neonatal nurse perceived value of kangaroo mother care and maternal care partnership in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Perinatol. 2013;30:875–80. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0033-1333675

Martin AE, D’Agostino JA, Passarella M, Lorch SA. Racial differences in parental satisfaction with neonatal intensive care unit nursing care. J Perinatol. 2016;36:1001–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/jp.2016.142

Witt RE, Malcolm M, Colvin BN, Gill MR, Ofori J, Roy S, et al. Racism and quality of neonatal intensive care: voices of black mothers. Pediatrics. 2022;150. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-056971

Witt RE, Colvin BN, Lenze SN, Forbes ES, Parker MGK, Hwang SS, et al. Lived experiences of stress of Black and Hispanic mothers during hospitalization of preterm infants in neonatal intensive care units. J Perinatol. 2022;42:195–201. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01241-0

Ajayi KV, Page R, Montour T, Garney WR, Wachira E, Adeyemi L. “We are suffering. Nothing is changing.” Black mother’s experiences, communication, and support in the neonatal intensive care unit in the United States: a qualitative study. Ethn Health. 2024;29:77–99. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2023.2259642

LaVeist TA. Disentangling race and socioeconomic status: a key to understanding health inequalities. J Urban Health. 2005;82:iii26–34. https://doi.org/10.1093/jurban/jti061

Powers SA, Taylor K, Tumin D, Kohler JA. Measuring parental presence in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Perinatol. 2022;39:134–43. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1715525

Carbado DW, Crenshaw KW, Mays VM, Tomlinson B. INTERSECTIONALITY: mapping the movements of a theory. Du Bois Rev. 2013;10:303–12. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1742058X13000349

Mahendran M, Lizotte D, Bauer GR. Quantitative methods for descriptive intersectional analysis with binary health outcomes. SSM Popul Health. 2022;17:101032 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2022.101032

Shuman A, Umble K, McCarty DB. Accuracy of electronic health record documentation of parental presence: A data validation and quality improvement analysis. Cureus. 2024. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.63110.

NC Medicaid. Managed Care Eligibility for Newborns: What Providers Need to Know. January 2023. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://medicaid.ncdhhs.gov/media/9529/open

RMH of Chapel Hill - Ronald McDonald House Charities of the Triangle. Accessed April 25, 2024. https://rmhctriangle.org/our-programs/rmh-of-chapel-hill/

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, Buchner A. G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods. 2007;39:175–91. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

Schober P, Vetter TR. Logistic regression in medical research. Anesth Analg. 2021;132:365–6. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000005247

StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software. StataCorp LLC; 2023.

Brown LP, York R, Jacobsen B, Gennaro S, Brooten D. Very low birth-weight infants: parental visiting and telephoning during initial infant hospitalization. Nurs Res. 1989;38:233–6.

Latva R, Lehtonen L, Salmelin RK, Tamminen T. Visiting less than every day: a marker for later behavioral problems in Finnish preterm infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2004;158:1153–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.12.1153

Garten L, Maass E, Schmalisch G, Bührer C. O father, where art thou? Parental NICU visiting patterns during the first 28 days of life of very low-birth-weight infants. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs. 2011;25:342–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/JPN.0b013e318233b8c3

Raiskila S, Axelin A, Toome L, Caballero S, Tandberg BS, Montirosso R, et al. Parents’ presence and parent-infant closeness in 11 neonatal intensive care units in six European countries vary between and within the countries. Acta Paediatr. 2017;106:878–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.13798

Hannah-Jones Nikole, New York Times Company. The 1619 Project: A New Origin Story. First. One World; 2021:400.

Klawetter S, Neu M, Roybal KL, Greenfield JC, Scott J, Hwang S. Mothering in the NICU: a qualitative exploration of maternal engagement. Soc Work Health Care. 2019;58:746–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/00981389.2019.1629152

Greenfield JC, Klawetter S. Parental leave policy as a strategy to improve outcomes among premature infants. Health Soc Work. 2016;41:17–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlv079

Callahan EJ, Brasted WS, Myerberg DZ, Hamilton S. Prolonged travel time to neonatal intensive care unit does not affect content of parental visiting: a controlled prospective study. J Rural Health. 1991;7:73–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-0361.1991.tb00705.x

Giacoia GP, Rutledge D, West K. Factors affecting visitation of sick newborns. Clin Pediatr (Philos). 1985;24:259–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/000992288502400506

Urban Institute. The Neighborhood Change in Urban America. Population Growth and Decline in City Neighborhoods. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/60281/310594-Population-Growth-and-Decline-in-City-Neighborhoods.PDF

Bourque SL, Weikel BW, Palau MA, Greenfield JC, Hall A, Klawetter S, et al. The association of social factors and time spent in the NICU for mothers of very preterm infants. Hosp Pediatr. 2021;11:988–96. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2021-005861

Gonya J, Nelin LD. Factors associated with maternal visitation and participation in skin-to-skin care in an all referral level IIIc NICU. Acta Paediatr. 2013;102:e53–6. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.12064

van Veenendaal NR, van Kempen AAMW, Franck LS, O’Brien K, Limpens J, van der Lee JH, et al. Hospitalising preterm infants in single family rooms versus open bay units: A systematic review and meta-analysis of impact on parents. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;23:100388 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100388

Saxton SN, Walker BL, Dukhovny D. Parents matter: examination of family presence in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Perinatol. 2021;38:1023–30. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1701506

Franck LS, Ferguson D, Fryda S, Rubin N. The child and family hospital experience: is it influenced by family accommodation. Med Care Res Rev. 2015;72:419–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558715579667

Bourque SL, Williams VN, Scott J, Hwang SS. The role of distance from home to hospital on parental experience in the NICU: a qualitative study. Children (Basel). 2023;10. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10091576

Spittle AJ, McKinnon C, Huang L, Burnett A, Cameron K, Doyle LW, et al. Missing out on precious time: Extending paid parental leave for parents of babies admitted to neonatal intensive or special care units for prolonged periods. J Paediatr Child Health. 2022;58:376–81. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.15836

McCarty DB, Ferrari RM, Golden S, Zvara BJ, Wilson WD, Shanahan ME. Identifying Facilitators and Barriers to Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Visitation in Mothers of Low Socioeconomic Status: A Qualitative Investigation. Children 2024;11:1390. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11111390

Witt D, Brawer R, Plumb J. Cultural factors in preventive care: African-Americans. Prim Care. 2002;29:487–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0095-4543(02)00009-x

Kalluri NS, Melvin P, Belfort MB, Gupta M, Cordova-Ramos EG, Parker MG. Maternal language disparities in neonatal intensive care unit outcomes. J Perinatol. 2022;42:723–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01250-z

Klawetter S, Greenfield JC, Speer SR, Brown K, Hwang SS. An integrative review: maternal engagement in the neonatal intensive care unit and health outcomes for U.S.-born preterm infants and their parents. AMS Public Health. 2019;6:160–83. https://doi.org/10.3934/publichealth.2019.2.160

Grundt H, Tandberg BS, Flacking R, Drageset J, Moen A. Associations between single-family room care and breastfeeding rates in preterm infants. J Hum Lact. 2021;37:593–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890334420962709

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted with support and resources provided by Chris Wiesen, PhD at the Odum Institute for Research in Social Science at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Funding

This research was funded by the Foundation for Physical Therapy Research, Promotion of Doctoral Studies Award (DM).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DM conceptualized and designed study, conducted and interpreted analyses, and drafted the manuscript; MS supervised all aspects of the research; MS, RF, SG, BZ, and WW contributed to the design of the study, interpretation of results, and contributed to manuscript revisions.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the Belmont Report of ethical principles for human subjects research. Approval was obtained from the UNC Office of Research Ethics and UNC Institutional Review Board (Reference ID 430343). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

McCarty, D.B., Golden, S.D., Ferrari, R.M. et al. Sociodemographic characteristics of maternal presence in neonatal intensive care: an intersectional analysis. J Perinatol 45, 1226–1232 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-02175-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-024-02175-z