Abstract

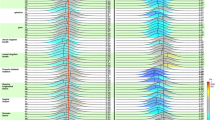

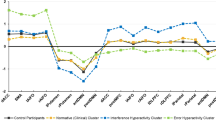

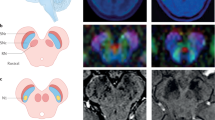

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is an impairing psychiatric condition, which often onsets in childhood. Growing research highlights dopaminergic alterations in adult OCD, yet pediatric studies are limited by methodological constraints. This is the first study to utilize neuromelanin-sensitive MRI as a proxy for dopaminergic function among children with OCD. N = 135 youth (6–14-year-olds) completed high-resolution neuromelanin-sensitive MRI across two sites; n = 64 had an OCD diagnosis. N = 47 children with OCD completed a second scan after cognitive-behavioral therapy. Voxel-wise analyses identified that neuromelanin-MRI signal was higher among children with OCD compared to those without (483 voxels, permutation-corrected p = 0.018). Effects were significant within both the substania nigra pars compacta (p = 0.004, Cohen’s d = 0.51) and ventral tegmental area (p = 0.006, d = 0.50). Follow-up analyses indicated that more severe lifetime symptoms (t = −2.72, p = 0.009) and longer illness duration (t = −2.22, p = 0.03) related to lower neuromelanin-MRI signal. Despite significant symptom reduction with therapy (p < 0.001, d = 1.44), neither baseline nor change in neuromelanin-MRI signal associated with symptom improvement. Current results provide the first demonstration of the utility of neuromelanin-MRI in pediatric psychiatry, specifically highlighting in vivo evidence for midbrain dopamine alterations in treatment-seeking youth with OCD. Neuromelanin-MRI likely indexes accumulating alterations over time, herein, implicating dopamine hyperactivity in OCD. Given evidence of increased neuromelanin signal in pediatric OCD but negative association with symptom severity, additional work is needed to parse potential longitudinal or compensatory mechanisms. Future studies should explore the utility of neuromelanin-MRI biomarkers to identify early risk prior to onset, parse OCD subtypes or symptom heterogeneity, and explore prediction of pharmacotherapy response.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abudy A, Juven-Wetzler A, Sonnino R, Zohar J. Serotonin and beyond: a neurotransmitter perspective of OCD. In: Obsessive-compulsive disorder. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. 220–43.

Sinopoli VM, Burton CL, Kronenberg S, Arnold PD. A review of the role of serotonin system genes in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2017;80:372–81.

Ivarsson T, Skarphedinsson G, Kornør H, Axelsdottir B, Biedilæ S, Heyman I, et al. The place of and evidence for serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) for obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) in children and adolescents: Views based on a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2015;227:93–103.

Kotapati VP, Khan AM, Dar S, Begum G, Bachu R, Adnan M, et al. The effectiveness of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adolescents and children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:523.

Koo MS, Kim EJ, Roh D, Kim CH. Role of dopamine in the pathophysiology and treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:275–90.

Denys D, Zohar J, Westenberg HG. The role of dopamine in obsessive-compulsive disorder: preclinical and clinical evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:11–7.

Westenberg HGM, Fineberg NA, Denys D. Neurobiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder:serotonin and beyond. CNS Spectr. 2007;12:14–27.

Wood J, Ahmari SE. A framework for understanding the emerging role of corticolimbic-ventral striatal networks in OCD-associated repetitive behaviors. Front Syst Neurosci. 2015;9:171.

Hesse S, Muller U, Lincke T, Barthel H, Villmann T, Angermeyer MC, et al. Serotonin and dopamine transporter imaging in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2005;140:63–72.

Perani D, Garibotto V, Gorini A, Moresco RM, Henin M, Panzacchi A, et al. In vivo PET study of 5HT(2A) serotonin and D(2) dopamine dysfunction in drug-naive obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuroimage. 2008;42:306–14.

Olver JS, O’Keefe G, Jones GR, Burrows GD, Tochon-Danguy HJ, Ackermann U, et al. Dopamine D1 receptor binding in the striatum of patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:321–6.

Kim C-H, Koo M-S, Cheon K-A, Ryu Y-H, Lee J-D, Lee H-S. Dopamine transporter density of basal ganglia assessed with [123I]IPT SPET in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:1637–43.

Denys D, de Vries F, Cath D, Figee M, Vulink N, Veltman DJ, et al. Dopaminergic activity in Tourette syndrome and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;23:1423–31.

van der Wee NJ, Stevens H, Hardeman JA, Mandl RC, Denys DA, van Megen HJ, et al. Enhanced dopamine transporter density in psychotropic-naive patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder shown by [123I]{beta}-CIT SPECT. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2201–6.

Voon V, Potenza MN, Thomsen T. Medication-related impulse control and repetitive behaviors in Parkinson’s disease. Curr Opin Neurol. 2007;20:484–92.

Voon V, Fox SH. Medication-related impulse control and repetitive behaviors in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:1089–96.

Sesia T, Bizup B, Grace AA. Evaluation of animal models of obsessive-compulsive disorder: correlation with phasic dopamine neuron activity. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2013;16:1295–307.

Turk AZ, Lotfi Marchoubeh M, Fritsch I, Maguire GA, SheikhBahaei S. Dopamine, vocalization, and astrocytes. Brain Lang. 2021;219:104970.

Kalueff AV, Stewart AM, Song C, Berridge KC, Graybiel AM, Fentress JC. Neurobiology of rodent self-grooming and its value for translational neuroscience. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016;17:45–59.

Cools R, D’Esposito M. Inverted-U-shaped dopamine actions on human working memory and cognitive control. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:e113–e125.

Cassidy CM, Zucca FA, Girgis RR, Baker SC, Weinstein JJ, Sharp ME, et al. Neuromelanin-sensitive MRI as a noninvasive proxy measure of dopamine function in the human brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:5108–17.

Sulzer D, Cassidy C, Horga G, Kang UJ, Fahn S, Casella L, et al. Neuromelanin detection by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and its promise as a biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2018;4:11.

Poulin J-F, Caronia G, Hofer C, Cui Q, Helm B, Ramakrishnan C, et al. Mapping projections of molecularly defined dopamine neuron subtypes using intersectional genetic approaches. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21:1260–71.

Sonne J, Reddy V, Beato MR. Neuroanatomy, Substantia Nigra. StatPearls: StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

Moore RY, Bloom FE. Central catecholamine neuron systems: anatomy and physiology of the dopamine systems. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1978;1:129–69.

Meiser J, Weindl D, Hiller K. Complexity of dopamine metabolism. Cell Commun Signal. 2013;11:34.

Zecca L, Zucca FA, Wilms H, Sulzer D. Neuromelanin of the substantia nigra: a neuronal black hole with protective and toxic characteristics. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:578–80.

Zecca L, Tampellini D, Gerlach M, Riederer P, Fariello RG, Sulzer D. Substantia nigra neuromelanin: structure, synthesis, and molecular behaviour. Mol Pathol. 2001;54:414–8.

Sulzer D, Bogulavsky J, Larsen KE, Behr G, Karatekin E, Kleinman MH, et al. Neuromelanin biosynthesis is driven by excess cytosolic catecholamines not accumulated by synaptic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11869–74.

Brammerloh M, Morawski M, Weigelt I, Reinert T, Lange C, Pelicon P, et al. Toward an early diagnostic marker of Parkinson’s: measuring iron in dopaminergic neurons with MR relaxometry. biorxiv. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.01.170563.

Ito H, Kawaguchi H, Kodaka F, Takuwa H, Ikoma Y, Shimada H, et al. Normative data of dopaminergic neurotransmission functions in substantia nigra measured with MRI and PET: Neuromelanin, dopamine synthesis, dopamine transporters, and dopamine D2 receptors. Neuroimage. 2017;158:12–7.

Langley J, Huddleston DE, Chen X, Sedlacik J, Zachariah N, Hu X. A multicontrast approach for comprehensive imaging of substantia nigra. Neuroimage. 2015;112:7–13.

Wengler K, He X, Abi-Dargham A, Horga G. Reproducibility assessment of neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging protocols for region-of-interest and voxelwise analyses. Neuroimage. 2019;208:116457.

van der Pluijm M, Cassidy C, Zandstra M, Wallert E, de Bruin K, Booij J, et al. Reliability and reproducibility of neuromelanin-sensitive imaging of the substantia nigra: a comparison of three different sequences. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021;53:712–21.

Castellanos G, Fernandez-Seara MA, Lorenzo-Betancor O, Ortega-Cubero S, Puigvert M, Uranga J, et al. Automated neuromelanin imaging as a diagnostic biomarker for Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2015;30:945–52.

Kawaguchi H, Shimada H, Kodaka F, Suzuki M, Shinotoh H, Hirano S, et al. Principal component analysis of multimodal neuromelanin MRI and dopamine transporter PET data provides a specific metric for the nigral dopaminergic neuronal density. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0151191.

Sasaki M, Shibata E, Tohyama K, Takahashi J, Otsuka K, Tsuchiya K, et al. Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging of locus ceruleus and substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease. Neuroreport 2006;17:1215–8.

Cho SJ, Bae YJ, Kim JM, Kim D, Baik SH, Sunwoo L, et al. Diagnostic performance of neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging for patients with Parkinson’s disease and factor analysis for its heterogeneity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radio. 2021;31:1268–80.

Wang L, Yan Y, Zhang L, Liu Y, Luo R, Chang Y. Substantia nigra neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging in patients with different subtypes of Parkinson disease. J Neural Transm. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00702-020-02295-8.

Biondetti E, Gaurav R, Yahia-Cherif L, Mangone G, Pyatigorskaya N, Valabregue R, et al. Spatiotemporal changes in substantia nigra neuromelanin content in Parkinson’s disease. Brain 2020;143:2757–70.

Kashihara K, Shinya T, Higaki F. Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging of nigral volume loss in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Clin Neurosci. 2011;18:1093–6.

Ohtsuka C, Sasaki M, Konno K, Kato K, Takahashi J, Yamashita F, et al. Differentiation of early-stage parkinsonisms using neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2014;20:755–60.

Ohtsuka C, Sasaki M, Konno K, Koide M, Kato K, Takahashi J, et al. Changes in substantia nigra and locus coeruleus in patients with early-stage Parkinson’s disease using neuromelanin-sensitive MR imaging. Neurosci Lett. 2013;541:93–8.

Reimão S, Ferreira S, Nunes RG, Pita Lobo P, Neutel D, Abreu D, et al. Magnetic resonance correlation of iron content with neuromelanin in the substantia nigra of early-stage Parkinson’s disease. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:368–74.

Safai A, Prasad S, Chougule T, Saini J, Pal PK, Ingalhalikar M. Microstructural abnormalities of substantia nigra in Parkinson’s disease: A neuromelanin sensitive MRI atlas based study. Hum Brain Mapp. 2020;41:1323–33.

Hirsch E, Graybiel AM, Agid YA. Melanized dopaminergic neurons are differentially susceptible to degeneration in Parkinson’s disease. Nature 1988;334:345–8.

Shibata E, Sasaki M, Tohyama K, Otsuka K, Endoh J, Terayama Y, et al. Use of neuromelanin-sensitive MRI to distinguish schizophrenic and depressive patients and healthy individuals based on signal alterations in the substantia nigra and locus ceruleus. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:401–6.

Watanabe Y, Tanaka H, Tsukabe A, Kunitomi Y, Nishizawa M, Hashimoto R, et al. Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging reveals increased dopaminergic neuron activity in the substantia nigra of patients with schizophrenia. PLoS One. 2014;9:e104619.

Yamashita F, Sasaki M, Fukumoto K, Otsuka K, Uwano I, Kameda H, et al. Detection of changes in the ventral tegmental area of patients with schizophrenia using neuromelanin-sensitive MRI. Neuroreport 2016;27:289–94.

Jalles C, Chendo I, Levy P, Reimão S. Neuromelanin changes in first episode psychosis with substance abuse. Schizophr Res. 2020;220:283–4.

Ueno F, Iwata Y, Nakajima S, Caravaggio F, Rubio JM, Horga G, et al. Neuromelanin accumulation in patients with schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;132:1205–13.

Van Der Pluijm M, De Haan L, Booij J, Van de Giessen E. Neuromelanin MRI as biomarker for treatment resistance in first episode schizophrenia patients. Neurosci Appl. 2022;1:100077.

Tavares M, Reimão S, Chendo I, Carvalho M, Levy P, Nunes RG. Neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging of the substantia nigra in first episode psychosis patients consumers of illicit substances. Schizophr Res. 2018;197:620–1.

Meltzer HY, Stahl SM. The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: a review. Schizophr Bull. 1976;2:19–76.

Zecca L, Fariello R, Riederer P, Sulzer D, Gatti A, Tampellini D. The absolute concentration of nigral neuromelanin, assayed by a new sensitive method, increases throughout the life and is dramatically decreased in Parkinson’s disease. FEBS Lett. 2002;510:216–20.

March JS, Franklin M, Nelson A, Foa E. Cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy for pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30:8–18.

March JS, Mulle K. OCD in children and adolescents. New York, NY: Guilford Publications; 1998.

Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao UMA, Flynn C, Moreci P, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–8.

Scahill L, Riddle MA, McSwiggin-Hardin M, Ort SI, King RA, Goodman WK, et al. Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale: reliability and validity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:844–52.

Hanna GL. Schedule for obsessive-compulsive and other behavioral syndromes (SOCOBS). Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2013.

Foa EB, Coles M, Huppert JD, Pasupuleti RV, Franklin ME, March J. Development and validation of a child version of the obsessive compulsive inventory. Behav Ther. 2010;41:121–32.

Casey BJ, Cannonier T, Conley MI, Cohen AO, Barch DM, Heitzeg MM, et al. The Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study: Imaging acquisition across 21 sites. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2018;32:43–54.

Wengler K, Ashinoff BK, Pueraro E, Cassidy CM, Horga G, Rutherford BR. Association between neuromelanin-sensitive MRI signal and psychomotor slowing in late-life depression. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021;46:1233–9.

Salzman G, Kim J, Horga G, Wengler K. Standardized data acquisition for neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging of the substantia nigra. J Vis Exp. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3791/62493.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2020. https://www.R-project.org/.

Pauli WM, Nili AN, Tyszka JM. A high-resolution probabilistic in vivo atlas of human subcortical brain nuclei. Sci Data. 2018;5:180063.

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–8.

Friedman J, Hastie T, Tibshirani R. Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. J Stat Softw. 2010;33:1–22.

Kelley AE, Stinus L. Disappearance of hoarding behavior after 6-hydroxydopamine lesions of the mesolimbic dopamine neurons and its reinstatement with l-dopa. Behav Neurosci. 1985;99:531–45.

McLaughlin T, Blum K, Steinberg B, Modestino EJ, Fried L, Baron D, et al. Pro-dopamine regulator, KB220Z, attenuates hoarding and shopping behavior in a female, diagnosed with SUD and ADHD. J Behav Addict. 2018;7:192–203.

O’Sullivan SS, Djamshidian A, Evans AH, Loane CM, Lees AJ, Lawrence AD. Excessive hoarding in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2010;25:1026–33.

Yang H-D, Wang Q, Wang Z, Wang D-H. Food hoarding and associated neuronal activation in brain reward circuitry in Mongolian gerbils. Physiol Behav. 2011;104:429–36.

Stein DJ, Seedat S, Potocnik F. Hoarding: a review. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 1999;36:35–46.

Abramowitz JS, Wheaton MG, Storch EA. The status of hoarding as a symptom of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46:1026–33.

Pertusa A, Fullana MA, Singh S, Alonso P, Menchón JM, Mataix-Cols D. Compulsive hoarding: OCD symptom, distinct clinical syndrome, or both? Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:1289–98.

Rachman S, Elliott CM, Shafran R, Radomsky AS. Separating hoarding from OCD. Behav Res Ther. 2009;47:520–2.

Samuels JF, Bienvenu OJ III, Pinto A, Fyer AJ, McCracken JT, Rauch SL, et al. Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder: results from the OCD Collaborative Genetics Study. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45:673–86.

Mataix-Cols D, Frost RO, Pertusa A, Clark LA, Saxena S, Leckman JF, et al. Hoarding disorder: a new diagnosis for DSM-V? Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:556–72.

Kellett S, Greenhalgh R, Beail N, Ridgway N. Compulsive hoarding: an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2010;38:141–55.

Black DW, Monahan P, Gable J, Blum N, Clancy G, Baker P. Hoarding and treatment response in 38 nondepressed subjects with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59:420–5.

Kings CA, Moulding R, Knight T. You are what you own: reviewing the link between possessions, emotional attachment, and the self-concept in hoarding disorder. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 2017;14:51–8.

Seedat S, Stein DJ. Hoarding in obsessive-compulsive disorder and related disorders: a preliminary report of 15 cases. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2002;56:17–23.

Frost RO, Gross RC. The hoarding of possessions. Behav Res Ther. 1993;31:367–81.

Grisham JR, Brown TA, Liverant GI, Campbell-Sills L. The distinctiveness of compulsive hoarding from obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2005;19:767–79.

Tolin DF. Understanding and treating hoarding: a biopsychosocial perspective. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67:517–26.

Shibata E, Sasaki M, Tohyama K, Kanbara Y, Otsuka K, Ehara S, et al. Age-related changes in locus ceruleus on neuromelanin magnetic resonance imaging at 3 Tesla. Magn Reson Med Sci. 2006;5:197–200.

Halliday GM, Fedorow H, Rickert CH, Gerlach M, Riederer P, Double KL. Evidence for specific phases in the development of human neuromelanin. J Neural Transm. 2006;113:721–8.

Horga G, Wengler K, Cassidy CM. Neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging as a proxy marker for catecholamine function in psychiatry. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:788–9.

Trujillo P, Petersen KJ, Cronin MJ, Lin Y-C, Kang H, Donahue MJ, et al. Quantitative magnetization transfer imaging of the human locus coeruleus. Neuroimage. 2019;200:191–8.

Watanabe T, Tan Z, Wang X, Martinez-Hernandez A, Frahm J. Magnetic resonance imaging of noradrenergic neurons. Brain Struct Funct. 2019;224:1609–25.

Cyr M, Pagliaccio D, Yanes-Lukin P, Fontaine M, Rynn MA, Marsh R. Altered network connectivity predicts response to cognitive-behavioral therapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:1232–40.

Cyr M, Pagliaccio D, Yanes-Lukin P, Goldberg P, Fontaine M, Rynn MA, et al. Altered fronto-amygdalar functional connectivity predicts response to cognitive behavioral therapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38:836–45.

Pagliaccio D, Middleton R, Hezel D, Steinman S, Snorrason I, Gershkovich M, et al. Task-based fMRI predicts response and remission to exposure therapy in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:20346–53.

Pagliaccio D, Cha J, He X, Cyr M, Yanes-Lukin P, Goldberg P, et al. Structural neural markers of response to cognitive behavioral therapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61:1299–308.

Shi TC, Pagliaccio D, Cyr M, Simpson HB, Marsh R. Network-based functional connectivity predicts response to exposure therapy in unmedicated adults with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021;46:1035–44.

Ducasse D, Boyer L, Michel P, Loundou A, Macgregor A, Micoulaud-Franchi JA, et al. D2 and D3 dopamine receptor affinity predicts effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in obsessive-compulsive disorders: a metaregression analysis. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:3765–70.

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by funds from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH115024, PIs: Marsh & Fitzgerald) as was the efforts of the authors: Dr. Pagliaccio (R21 MH125044, R01 MH126181), Dr. Horga (R01 MH117323, R01 MH114965), Dr. Wengler (F32 MH125540). Preliminary findings from this work were presented at the 2021 meeting of the Society for Biological Psychiatry (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.02.212). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Pagliaccio confirms that he had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DP analyzed study data and prepared the manuscript. KW and GH developed the neuromelanin-MRI protocol and processing pipeline. MF oversaw MRI data collection and quality control. KD, HB, and EB conducted and oversaw clinical assessment procedures. MR, SP, and CR collected study data and performed data quality control. DP, KDF, and RM designed the study and oversaw study procedures. All authors contributed to manuscript review and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

KW and GH report having filed patents for analysis and use of neuromelanin imaging in central nervous system disorders, licensed to Terran Biosciences, but have received no royalties. All other authors reported no biomedical financial interests or potential conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pagliaccio, D., Wengler, K., Durham, K. et al. Probing midbrain dopamine function in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder via neuromelanin-sensitive magnetic resonance imaging. Mol Psychiatry 28, 3075–3082 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02105-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-023-02105-z

This article is cited by

-

Neuromelanin-sensitive MRI for mechanistic research and biomarker development in psychiatry

Neuropsychopharmacology (2025)

-

Neurobiology of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder from Genes to Circuits: Insights from Animal Models

Neuroscience Bulletin (2024)