Abstract

Temperament can be conceptualized as the baseline configuration of experience and behavior, contributing to individual differences in activity levels, emotional intensity, and thought patterns. This work aimed to investigate the biological correlates of temperament. First, we performed systematic reviews on the relationship of temperament with the brain’s function/structure (characterized via neuroimaging), as well as neurotransmitter signaling (measured in cerebrospinal fluid and blood). Then, we investigated the relationship of temperament with intrinsic brain activity (using resting-state functional MRI) in 122 subjects, as well as dopamine and serotonin levels (measured in platelets) in 25 subjects. The systematic reviews showed heterogeneous data. Our empirical studies showed that: the hyperthymic temperament is associated with decreased intrinsic brain activity in the medial prefrontal cortex/default-mode network, along with increased dopamine levels in platelets; conversely, the depressive temperament is associated with increased intrinsic brain activity in the medial prefrontal cortex/default-mode network, along with decreased dopamine levels in platelets. These data suggest that the hyperthymic temperament may be associated with a baseline configuration of brain activity tilted toward the sensorimotor areas at the expense of the associative areas (related to high dopamine signaling), favoring immediate interaction with the environment and a propensity for action and impulsive behavior; conversely, the depressive temperament may be associated with a baseline configuration of brain activity tilted toward the associative areas at the expense of the sensorimotor areas (related to low dopamine signaling), favoring detachment from the environment and a propensity for thinking/imagery and rumination. Accordingly, these temperaments may represent the physiological counterparts of the manic and depressive states of bipolar disorder.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during this study, as well as the codes used, are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

Favaretto E, Bedani F, Brancati GE, De Berardis D, Giovannini S, Scarcella L, et al. Synthesising 30 years of clinical experience and scientific insight on affective temperaments in psychiatric disorders: State of the art. J Affect Disord. 2024;362:406–15.

Goldsmith HH, Buss AH, Plomin R, Rothbart MK, Thomas A, Chess S, et al. Roundtable: what is temperament? Four approaches. Child Dev. 1987;58:505–29.

Kraepelin E. Manic depressive insanity and paranoia. Edinburgh: E. & S. Livingstone; 1921.

Strelau J. Temperament: a psychological perspective. New York: Plenum Press; 1998.

Akiskal KK, Akiskal HS. The theoretical underpinnings of affective temperaments: implications for evolutionary foundations of bipolar disorder and human nature. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:231–9.

Akiskal HS, Akiskal KK. TEMPS: temperament evaluation of memphis, pisa, Paris and San Diego. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:1–2.

Rovai L, Maremmani AG, Rugani F, Bacciardi S, Pacini M, Dell’Osso L, et al. Do Akiskal & Mallya’s affective temperaments belong to the domain of pathology or to that of normality? Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2013;17:2065–79.

Amaral DG, Strick PL The organization of the central nervous system. In: Kandel E, Schwartz J, Jessell T, Siegelbaum S, Hudspeth A Principles of neural science - Fifth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

Margulies DS, Ghosh SS, Goulas A, Falkiewicz M, Huntenburg JM, Langs G, et al. Situating the default-mode network along a principal gradient of macroscale cortical organization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:12574–9.

Huntenburg JM, Bazin PL, Margulies DS. Large-scale gradients in human cortical organization. Trends Cogn Sci. 2018;22:21–31.

Buzsaki G. Rhythms of the brain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006.

Zuo XN, Di Martino A, Kelly C, Shehzad ZE, Gee DG, Klein DF, et al. The oscillating brain: complex and reliable. Neuroimage. 2010;49:1432–45.

Gong ZQ, Zuo XN. Connectivity gradients in spontaneous brain activity at multiple frequency bands. Cereb Cortex. 2023;33:9718–28.

Gong ZQ, Zuo XN. Dark brain energy: Toward an integrative model of spontaneous slow oscillations. Phys Life Rev. 2025;52:278–97.

Amaral D The functional organization of perception and movement. In: Kandel E, Schwartz J, Jessell T, Siegelbaum S, Hudspeth A Principles of neural science - Fifth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012.

Craig AD. How do you feel? Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:655–66.

Evrard HC. The organization of the primate insular cortex. Front Neuroanat. 2019;13:43.

Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–41.

Seeley WW, Menon V, Schatzberg AF, Keller J, Glover GH, Kenna H, et al. Dissociable intrinsic connectivity networks for salience processing and executive control. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2349–56.

Yeo BT, Krienen FM, Sepulcre J, Sabuncu MR, Lashkari D, Hollinshead M, et al. The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity. J Neurophysiol. 2011;106:1125–65.

Wang P, Kong R, Kong X, Liegeois R, Orban C, Deco G, et al. Inversion of a large-scale circuit model reveals a cortical hierarchy in the dynamic resting human brain. Sci Adv. 2019;5:eaat7854.

Singer W. Neuronal synchrony: a versatile code for the definition of relations? Neuron. 1999;24:49–65. 111-125.

Dosenbach NU, Fair DA, Cohen AL, Schlaggar BL, Petersen SE. A dual-networks architecture of top-down control. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:99–105.

Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:676–82.

Raichle ME. The brain’s default mode network. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2015;38:433–47.

Buckner RL, Andrews-Hanna JR, Schacter DL. The brain’s default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1124:1–38.

Murphy C, Jefferies E, Rueschemeyer SA, Sormaz M, Wang HT, Margulies DS, et al. Distant from input: Evidence of regions within the default mode network supporting perceptually-decoupled and conceptually-guided cognition. Neuroimage. 2018;171:393–401.

Olson CR, Colby CL The organization of cognition. In: Kandel E, Schwartz J, Jessell T, Siegelbaum S, Hudspeth A Principles of neural science - Fifth edition. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

Bar M, Aminoff E, Mason M, Fenske M. The units of thought. Hippocampus. 2007;17:420–8.

Smallwood J. Distinguishing how from why the mind wanders: a process-occurrence framework for self-generated mental activity. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:519–35.

Conio B, Martino M, Magioncalda P, Escelsior A, Inglese M, Amore M, et al. Opposite effects of dopamine and serotonin on resting-state networks: review and implications for psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:82–93.

Bartholomew RA, Li H, Gaidis EJ, Stackmann M, Shoemaker CT, Rossi MA, et al. Striatonigral control of movement velocity in mice. Eur J Neurosci. 2016;43:1097–110.

Bentivoglio M, Morelli M Chapter I the organization and circuits of mesencephalic dopaminergic neurons and the distribution of dopamine receptors in the brain. In: Dunnett SB, Bentivoglio M, Björklund A, Hökfelt T Handbook of chemical neuroanatomy, 21: Dopamine. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science; 2005.

Dugue GP, Lorincz ML, Lottem E, Audero E, Matias S, Correia PA, et al. Optogenetic recruitment of dorsal raphe serotonergic neurons acutely decreases mechanosensory responsivity in behaving mice. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e105941.

Correia PA, Lottem E, Banerjee D, Machado AS, Carey MR, Mainen ZF. Transient inhibition and long-term facilitation of locomotion by phasic optogenetic activation of serotonin neurons. eLife. 2017;6:e20975.

Miyazaki KW, Miyazaki K, Tanaka KF, Yamanaka A, Takahashi A, Tabuchi S, et al. Optogenetic activation of dorsal raphe serotonin neurons enhances patience for future rewards. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2033–40.

Uchida N, Cohen JY. Slow motion. eLife. 2017;6:e20975.

McDannald MA. Serotonin: waiting but not rewarding. Curr Biol. 2015;25:R103–R104.

Ranade S, Pi HJ, Kepecs A. Neuroscience: waiting for serotonin. Curr Biol. 2014;24:R803–805.

Jacobs BL, Azmitia EC. Structure and function of the brain serotonin system. Physiol Rev. 1992;72:165–229.

Mosienko V, Beis D, Pasqualetti M, Waider J, Matthes S, Qadri F, et al. Life without brain serotonin: reevaluation of serotonin function with mice deficient in brain serotonin synthesis. Behav Brain Res. 2015;277:78–88.

Burnouf T, Walker TL. The multifaceted role of platelets in mediating brain function. Blood. 2022;140:815–27.

Canobbio I. Blood platelets: circulating mirrors of neurons? Res Pract Thromb Haemost. 2019;3:564–5.

Audhya T, Adams JB, Johansen L. Correlation of serotonin levels in CSF, platelets, plasma, and urine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:1496–501.

Chou ML, Babamale AO, Walker TL, Cognasse F, Blum D, Burnouf T. Blood-brain crosstalk: the roles of neutrophils, platelets, and neutrophil extracellular traps in neuropathologies. Trends Neurosci. 2023;46:764–79.

Martino M, Magioncalda P. A three-dimensional model of neural activity and phenomenal-behavioral patterns. Mol Psychiatry. 2024;29:639–52.

Martino M, Magioncalda P. Tracing the psychopathology of bipolar disorder to the functional architecture of intrinsic brain activity and its neurotransmitter modulation: a three-dimensional model. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:793–802.

Magioncalda P, Martino M. A unified model of the pathophysiology of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:202–11.

Wu H, Zheng Y, Zhan Q, Dong J, Peng H, Zhai J, et al. Covariation between spontaneous neural activity in the insula and affective temperaments is related to sleep disturbance in individuals with major depressive disorder. Psychol Med. 2021;51:731–40.

Conio B, Magioncalda P, Martino M, Tumati S, Capobianco L, Escelsior A, et al. Opposing patterns of neuronal variability in the sensorimotor network mediate cyclothymic and depressive temperaments. Hum Brain Mapp. 2019;40:1344–52.

Nilsson T, Bromander S, Anckarsater R, Kristiansson M, Forsman A, Blennow K, et al. Neurochemical measures co-vary with personality traits: forensic psychiatric findings replicated in a general population sample. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:525–30.

Hansen JY, Shafiei G, Markello RD, Smart K, Cox SML, Norgaard M, et al. Mapping neurotransmitter systems to the structural and functional organization of the human neocortex. Nat Neurosci. 2022;25:1569–81.

Rocchi G, Sterlini B, Tardito S, Inglese M, Corradi A, Filaci G, et al. Opioidergic system and functional architecture of intrinsic brain activity: implications for psychiatric disorders. Neuroscientist. 2020;26:343–58.

Akiskal HS, Akiskal K. Cyclothymic, hyperthymic, and depressive temperaments as subaffective variants of mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;11:43–62.

Akiskal HS, Mallya G. Criteria for the “Soft” bipolar spectrum: treatment. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1987;23:68–73.

Perugi G, Toni C, Maremmani I, Tusini G, Ramacciotti S, Madia A, et al. The influence of affective temperaments and psychopathological traits on the definition of bipolar disorder subtypes: a study on bipolar I Italian national sample. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:e41–e49.

Martino M, Magioncalda P, Huang Z, Conio B, Piaggio N, Duncan NW, et al. Contrasting variability patterns in the default mode and sensorimotor networks balance in bipolar depression and mania. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:4824–9.

Russo D, Martino M, Magioncalda P, Inglese M, Amore M, Northoff G. Opposing changes in the functional architecture of large-scale networks in bipolar mania and depression. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46:971–80.

Zhang J, Magioncalda P, Huang Z, Tan Z, Hu X, Hu Z, et al. Altered global signal topography and its different regional localization in motor cortex and hippocampus in mania and depression. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:902–10.

Magioncalda P, Martino M, Conio B, Escelsior A, Piaggio N, Presta A, et al. Functional connectivity and neuronal variability of resting state activity in bipolar disorder–reduction and decoupling in anterior cortical midline structures. Hum Brain Mapp. 2015;36:666–82.

Zhang Y, Huang C, Zhao J, Liu Y, Xia M, Wang X, et al. Dysfunction in sensorimotor and default mode networks in major depressive disorder with insights from global brain connectivity. Nat Ment Health. 2024;2:1371–81.

Lynch CJ, Elbau IG, Ng T, Ayaz A, Zhu S, Wolk D, et al. Frontostriatal salience network expansion in individuals in depression. Nature. 2024;633:624–33.

Cloninger CR, Svrakic DM, Przybeck TR. A psychobiological model of temperament and character. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:975–90.

Kagan J, Reznick JS, Clarke C, Snidman N, Garcia-Coll C. Behavioral inhibition to the unfamiliar. Child Dev. 1984;55:2212–25.

Zuo XN, Xing XX. Test-retest reliabilities of resting-state FMRI measurements in human brain functional connectomics: a systems neuroscience perspective. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2014;45:100–18.

Zuo XN, Xu T, Milham MP. Harnessing reliability for neuroscience research. Nat Hum Behav. 2019;3:768–71.

Dong HM, Margulies DS, Zuo XN, Holmes AJ. Shifting gradients of macroscale cortical organization mark the transition from childhood to adolescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118:e2024448118.

Dong HM, Zhang XH, Labache L, Zhang S, Ooi LQR, Yeo BTT, et al. Ventral attention network connectivity is linked to cortical maturation and cognitive ability in childhood. Nat Neurosci. 2024;27:2009–20.

Zhou ZX, Zuo XN. Editorial: lifespan connectome gradients for a road to mental health. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;63:25–28.

Gong Z, Biswal BB, Zuo X. Paradigm shift in psychiatric neuroscience: multidimensional integrative theory. MedlinePlus. 2024;1:100024.

Bethlehem RAI, Seidlitz J, White SR, Vogel JW, Anderson KM, Adamson C, et al. Brain charts for the human lifespan. Nature. 2022;604:525–33.

Zhou ZX, Chen LZ, Milham MP, Zuo XN. Six cornerstones for translational brain charts. Sci Bull. 2023;68:795–9.

Acknowledgements

MM received support from the Taiwan National Science and Technology Council (113-2628-B-038-010-MY3), Taipei Medical University (TMU112-F-001), and Higher Education Sprout Project of the Taiwan Ministry of Education (DP2-TMU-113-N-07; DP2-TMU-114-N-07). PM received support from the Taiwan National Science and Technology Council (110-2628-B-038-015; 111-2628-B-038-023; 112-2628-B-038-006; 113-2314-B-038-096-MY3) and Taipei Medical University (TMU111-AE1-B38). The authors thank Jeanette Yang for her valuable contribution to participant recruitment and data collection for sample II. The authors thank Shou-Cheng Lu, Li-Ping Yuan, and Min-Hua Lin, as well as the Department of Laboratory Medicine and the Blood Sampling Center at Shuang Ho Hospital (New Taipei City, Taiwan), for their assistance with blood sample collection and analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

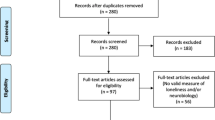

HTC conducted the umbrella review on the relationship of temperament with brain function and structure (including literature search, screening, and data extraction and elaboration), contributed to participant recruitment and data collection (sample II), contributed to the neuroimaging analysis, and contributed to writing the manuscript. ED performed the neuroimaging analysis. FRT conducted the platelet analysis. LS conducted the umbrella review on the relationship of temperament with neurotransmitter signaling (including literature search, screening, and data extraction and elaboration) and assisted with the platelet analysis. BC was responsible for participant recruitment and data collection (sample I) and contributed to the design of the empirical study on the relationship of temperament with intrinsic brain activity. MA supervised participant recruitment and data collection (sample I) and contributed to the design of the empirical study on the relationship of temperament with intrinsic brain activity. TB contributed to the design and supervision of the empirical study on the relationship of temperament with neurotransmitter signaling, and contributed to writing the manuscript. MM and PM conceived the study, supervised the overall project, interpreted the results, developed the theoretical framework, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods used in this work were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The empirical study on the relationship of temperament with intrinsic brain activity was approved by the Ethics Committee of San Martino Polyclinic Hospital (No. 82/13), and the empirical study on the relationship of temperament with neurotransmitter signaling was approved by the Joint Institutional Review Board of Taipei Medical University (N202102049). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, H.T., Martino, M., Dabiri, E. et al. Biological correlates of temperament: systematic reviews, empirical studies, and a conceptual framework linking neurotransmitter signaling, intrinsic brain activity, and the hyperthymic-depressive spectrum. Mol Psychiatry 30, 5880–5888 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03146-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03146-2