Abstract

Mental or neuropsychiatric disorders are widespread within our societies affecting one in every four people in the world. Very often the onset of a mental disorder (MD) occurs in early childhood and substantially reduces the quality of later life. Although the global burden of MDs is rising, mental health care is still suboptimal, partly due to insufficient understanding of the processes of disease development. New insights are needed to respond to this worldwide health problem. Next to the growing burden of MDs, there is a tendency to postpone pregnancy for various economic and practical reasons. In this review, we describe the current knowledge on the potential effect from advanced paternal age (APA) on development of autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and Tourette syndrome. Although literature did not clearly define an age cut-off for APA, we here present a comprehensive multifactorial model for the development of MDs, including the role of aging, de novo mutations, epigenetic mechanisms, psychosocial environment, and selection into late fatherhood. Our model is part of the Paternal Origins of Health and Disease paradigm and may serve as a foundation for future epidemiological research designs. This blueprint will increase the understanding of the etiology of MDs and can be used as a practical guide for clinicians favoring early detection and developing a tailored treatment plan. Ultimately, this will help health policy practitioners to prevent the development of MDs and to inform health-care workers and the community about disease determinants. Better knowledge of the proportion of all risk factors, their interactions, and their role in the development of MDs will lead to an optimization of mental health care and management.

Impact

-

We design a model of causation for MDs, integrating male aging, (epi)genetics, and environmental influences.

-

It adds new insights into the current knowledge about associations between APA and MDs.

-

In clinical practice, this comprehensive model may be helpful in early diagnosis and in treatment adopting a personal approach. It may help in identifying the proximate cause on an individual level or in a specific subpopulation. Besides the opportunity to measure the attributed proportions of risk factors, this model may be used as a blueprint to design prevention strategies for public health purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

World Health Organisation. Mental Disorders Affect One in Four People, Vol. 180, 29–34 (World Health Organization, 2001).

James, S. L. et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 Diseases and Injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 392, 1789–1858 (2018).

Regional Office for Africa. Atlas of Africa health statistics. https://aho.afro.who.int/data-and-statistics/af (2014).

Maselko, J. Social epidemiology and global mental health: expanding the evidence from high-income to low- and middle-income countries. Curr. Epidemiol. Rep. 4, 166–173 (2017).

WHO. Mental disorders. https://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-disorders (2019).

Schraeder, K. E. & Reid, G. J. Why wait? The effect of wait-times on subsequent help-seeking among families looking for children’s mental health services. J. Abnorm. Child Psychol. 43, 553–565 (2015).

Randall, M. et al. Diagnosing autism: Australian paediatric research network surveys. J. Paediatr. Child Health 52, 11–17 (2016).

Young, S. et al. Guidance for identification and treatment of individuals with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder based upon expert consensus. BMC Med. 18, 146, https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01585-y (2020).

World Health Organization. mhGAP Intervention Guide—For Mental, Neurological and Substance Abuse Disorders in Non-Specialized Health Settings. WHO Mental Health Gap Action Programme (mhGAP), 1–121 (WHO, 2016).

Hyman, S. L., Levy, S. E. & Myers, S. M. Identification, evaluation, and management of children with autism spectrum disorder. Pediatrics 145, e20193447 (2020).

Reiss, F. Socioeconomic inequalities and mental health problems in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Soc. Sci. Med. 90, 24–31 (2013).

Patalay, P. & Fitzsimons, E. Correlates of Mental Illness and Wellbeing in Children: Are They the Same? Results From the UK Millennium Cohort Study; J. Am. Acad.Child Adolesc. Psychiatry, Vol. 55, 771–783 (Dr. Dietrich Steinkopff, 2016).

Posner, J., Polanczyk, G. V. & Sonuga-Barke, E. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 395, 450–462 (2020).

Van Cauwenbergh, O., Di Serafino, A., Tytgat, J. & Soubry, A. Transgenerational epigenetic effects from male exposure to endocrine-disrupting compounds: a systematic review on research in mammals. Clin. Epigenet. 12, 65, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-020-00845-1 (2020).

Soubry, A., Hoyo, C., Jirtle, R. L. & Murphy, S. K. A paternal environmental legacy: evidence for epigenetic inheritance through the male germ line. BioEssays 36, 359–371 (2014).

Goyal, D. K. & Miyan, J. A. Neuro-immune abnormalities in autism and their relationship with the environment: a variable insult model for autism. Front. Endocrinol. 5, 29 (2014).

Schubert, C. Male biological clock possibly linked to autism, other disorders. Nat. Med. 14, 1170 (2008).

Greenberg, D. R. et al. Disease burden in offspring is associated with changing paternal demographics in the United States. Andrology 8, 342–347 (2020).

Brandt, J. S., Cruz Ithier, M. A., Rosen, T. & Ashkinadze, E. Advanced paternal age, infertility, and reproductive risks: a review of the literature. Prenatal Diagn. 39, 81–87 (2019).

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) (APA, 2013).

Sinzig, J. Autism spectrum disorders. Monatsschr. Kinderheilkd. 163, 673–680 (2015).

Wu, S. et al. Advanced parental age and autism risk in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 135, 29–41 (2017).

Wang, C., Geng, H., Liu, W. & Zhang, G. Prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal factors associated with autism: a meta-analysis. Medicine 96, e6696 (2017).

Oldereid, N. B. et al. The effect of paternal factors on perinatal and paediatric outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 24, 320–389 (2018).

Gao, Y. et al. Association of grandparental and parental age at childbirth with autism spectrum disorder in children. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e202868 (2020).

Janecka, M. et al. Parental age and differential estimates of risk for neuropsychiatric disorders: findings from the Danish Birth Cohort. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2018.09.447 (2019).

Merikangas, A. K. et al. Parental age and offspring psychopathology in the Philadelphia neurodevelopmental cohort. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 56, 391–400 (2017).

Geetha, B., Sukumar, C., Dhivyadeepa, E., Reddy, J. K. & Balachandar, V. Autism in India: a case–control study to understand the association between socio-economic and environmental risk factors. Acta Neurol. Belg. 119, 393–401 (2019).

Khaiman, C., Onnuam, K., Photchanakaew, S., Chonchaiya, W. & Suphapeetiporn, K. Risk factors for autism spectrum disorder in the Thai population. Eur. J. Pediatr. 174, 1365–1372 (2015).

Frans, E. M. & Sandin, S. Autism risk across generations: a population based study of advancing grandpaternal and paternal age. JAMA Psychiatry 70, 516 (2013).

WHO. Schizophrenia. WHO https://www.who.int/topics/schizophrenia/en/ (2014).

Weiser, M. et al. Understanding the association between advanced paternal age and schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Psychol. Med. 50, 431–437 (2020).

Wohl, M. & Gorwood, P. Paternal ages below or above 35 years old are associated with a different risk of schizophrenia in the offspring. Eur. Psychiatry 22, 22–26 (2007).

Miller, B. et al. Meta-analysis of paternal age and schizophrenia risk in male versus female offspring. Schizophr. Bull. 37, 1039–1047 (2011).

Cao, B. et al. Parental characteristics and the risk of schizophrenia in a Chinese population: a case-control study. Nord. J. Psychiatry 73, 90–95 (2019).

Panagiotidis, P. et al. Paternal and maternal age as risk factors for schizophrenia: a case–control study. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 22, 170–176 (2017).

Buizer-Voskamp, J. E. et al. Paternal age and psychiatric disorders: findings from a Dutch population registry. Schizophr. Res. 129, 128–132 (2011).

Wu, Y. et al. Advanced paternal age increases the risk of schizophrenia and obsessive–compulsive disorder in a Chinese Han population. Psychiatry Res. 198, 353–359 (2012).

de Kluiver, H., Buizer-Voskamp, J. E., Dolan, C. V. & Boomsma, D. I. Paternal age and psychiatric disorders: a review. Am. J. Med. Geneti. B 174, 202–213 (2017).

Frans, E. M. et al. Advanced paternal and grandpaternal age and schizophrenia: a three-generation perspective. Schizophr. Res. 133, 120–124 (2011).

Hvolgaard Mikkelsen, S., Olsen, J., Bech, B. H. & Obel, C. Parental age and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Int. J. Epidemiol. 46, 409–420 (2017).

McGrath, J. J. et al. A comprehensive assessment of parental age and psychiatric disorders. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 301–309 (2014).

D’Onofrio, B. M. et al. Paternal age at childbearing and offspring psychiatric and academic morbidity. JAMA Psychiatry 71, 432–438 (2014).

Chudal, R. et al. Parental age and the risk of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a nationwide, population-based cohort study. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 54, 487–494.e1 (2015).

Shimada, T. et al. Parental age and assisted reproductive technology in autism spectrum disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and Tourette syndrome in a Japanese population. Res. Autism Spectr. Disord 6, 500–507 (2011).

Cho, Y. J., Choi, R., Park, S. & Kwon, J. Parental smoking and depression, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: Korean national health and nutrition examination survey 2005-2014. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry 10, e12327 (2018).

St. Sauver, J. L. et al. Early life risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clin. Proc. 79, 1124–1131 (2004).

Gabis, L., Raz, R. & Kesner-Baruch, Y. Paternal age in autism spectrum disorders and ADHD. Pediatr. Neurol. 43, 300–302 (2010).

Wang, X. et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder risk: interaction between parental age and maternal history of attention- deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J. Dev. Behav. Pediatr. 00, 1–9 (2019).

Frans, E. M. et al. Advancing paternal age and bipolar disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 65, 1034–1040 (2008).

Byars, S. G. & Boomsma, J. J. Opposite differential risks for autism and schizophrenia based on maternal age, paternal age, and parental age differences. Evol. Med. Public Health 2016, 286–298 (2016).

Menezes, P. R. et al. Paternal and maternal ages at conception and risk of bipolar affective disorder in their offspring. Psychol. Med. 40, 477–485 (2010).

Laursen, T. M., Munk-Olsen, T., Nordentoft, M. & Mortensen, P. B. A comparison of selected risk factors for unipolar depressive disorder, bipolar affective disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia from a Danish population-based cohort. J. Clin. Psychiatry 68, 1673–1681 (2007).

Lehrer, D. S. et al. Paternal age effect: replication in schizophrenia with intriguing dissociation between bipolar with and without psychosis. Am. J. Med. Genet. B 171, 495–505 (2016).

Chudal, R. et al. Parental age and the risk of bipolar disorders. Bipolar Disord. 16, 624–632 (2014).

Brown, A., Bao, Y., McKeague, I., Shen, L. & Schaefer, C. Parental age and risk of bipolar disorder in offspring. Psychiatry Res. 208, 225–231 (2013).

Fountoulakis, K. N. et al. A case-control study of paternal and maternal age as risk factors in mood disorders. Int. J. Psychiatry Clin. Pract. 23, 90–98 (2019).

Chudal, R., Leivonen, S., Rintala, H., Hinkka-Yli-Salomäki, S. & Sourander, A. Parental age and the risk of obsessive compulsive disorder and Tourette syndrome/chronic tic disorder in a nationwide population-based sample. J. Affect. Disord. 223, 101–105 (2017).

Steinhausen, H. C., Bisgaard, C., Munk-Jørgensen, P. & Helenius, D. Family aggregation and risk factors of obsessive-compulsive disorders in a nationwide three-generation study. Depress. Anxiety 30, 1177–1184 (2013).

Brander, G. et al. Association of perinatal risk factors with obsessive-compulsive disorder a population-based birth cohort, sibling control study. JAMA Psychiatry 73, 1135–1144 (2016).

Brander, G., Pérez-Vigil, A., Larsson, H. & Mataix-Cols, D. Systematic review of environmental risk factors for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: a proposed roadmap from association to causation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 65, 36–62 (2016).

Chao, T.-K., Hu, J. & Pringsheim, T. Prenatal risk factors for Fourette syndrome: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14, 53 (2014).

The National Institute of Mental Health Information Resource Center. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/research/research-funded-by-nimh/rdoc/index.shtml (2020).

Rosenfield, P. J. et al. Later paternal age and sex differences in schizophrenia symptoms. Schizophr Res. 116, 191 (2010).

Opler, M. et al. Effect of parental age on treatment response in adolescents with schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. 151, 185–190 (2013).

Foutz, J. & Mezuk, B. Advanced paternal age and risk of psychotic-like symptoms in adult offspring. Schizophr. Res. 165, 123–127 (2015).

Romanus, S., Neven, P. & Soubry, A. Extending the developmental origins of health and disease theory: does paternal diet contribute to breast cancer risk in daughters? Breast Cancer Res. 18, 103, https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-016-0760-y (2016).

Soubry, A. Epigenetics as a driver of developmental origins of health and disease: did we forget the fathers? BioEssays 40, 1700113, https://doi.org/10.1002/bies.201700113 (2018).

Yin, J. & Schaaf, C. P. Autism genetics – an overview. Prenat. Diagn. 37, 14–30 (2017).

Foley, C., Corvin, A. & Nakagome, S. Genetics of schizophrenia: ready to translate? Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 19, 61 (2017).

Faraone, S. V. & Larsson, H. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol. Psychiatry 24, 562–575 (2019).

Stefansson, H. et al. Large recurrent microdeletions associated with schizophrenia. Nature 455, 232–236 (2008).

Xu, B. et al. Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with sporadic schizophrenia. Nat. Genet. 40, 880–885 (2008).

Frans, E. M., Lichtenstein, P., Hultman, C. M. & Kuja-Halkola, R. Age at fatherhood: heritability and associations with psychiatric disorders. Psychol. Med. 46, 2981–2988 (2016).

Malaspina, D. Paternal factors and schizophrenia risk: de novo mutations and imprinting. Schizophr. Bull. 27, 379–393 (2001).

Kennedy, J., Goudie, D. & Al, E. KAT6A syndrome: genotype–phenotype correlation in 76 patients with pathogenic KAT6A variants. Genet. Med. 21, 850–860 (2019).

Wilfert, A. B., Sulovari, A., Turner, T. N., Coe, B. P. & Eichler, E. E. Recurrent de novo mutations in neurodevelopmental disorders: properties and clinical implications. Genome Med. 9, 101 (2017).

O’ Roak, B. J. et al. Sporadic autism exomes reveal a highly interconnected protein network of de novo mutations. Nature 485, 246–250 (2012).

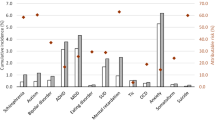

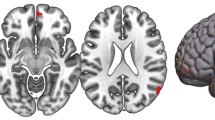

Kojima, M. et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of advanced paternal and maternal age at birth in autism spectrum disorder. Cereb. Cortex 29, 2524–2532 (2018).

Holmes, G. E., Bernstein, C. & Bernstein, H. Oxidative and other DNA damages as the basis of aging: a review. Mutat. Res. DNAging 275, 305–315 (1992).

Cawthon, R. M. et al. Germline mutation rates in young adults predict longevity and reproductive lifespan. Sci. Rep. 10, 10001 (2020).

Taylor, J. et al. Paternal-age-related de novo mutations and risk for five disorders. Nat. Commun. 10, 3043 (2019).

Janecka, M. et al. Advanced paternal age effects in neurodevelopmental disorders-review of potential underlying mechanisms. Transl. Psychiatry 7, e1019 (2017).

Kong, A. et al. Rate of de novo mutations and the importance of father-s age to disease risk. Nature 488, 471–475 (2012).

Goriely, A., McGrath, J. J., Hultman, C. M., Wilkie, A. O. M. & Malaspina, D. ‘Selfish spermatogonial selection’: a novel mechanism for the association between advanced paternal age and neurodevelopmental disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 170, 599–608 (2013).

Oldereid, N. B. et al. The effect of paternal factors on perinatal and paediatric outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum. Reprod. Update 24, 320–389 (2018).

Petersen, L., Mortensen, P. B. & Pedersen, C. B. Paternal age at birth of first child and risk of schizophrenia. Am. J. Psychiatry 168, 82–88 (2011).

Ek, M., Wicks, S., Svensson, A. C., Idring, S. & Dalman, C. Advancing paternal age and schizophrenia: the impact of delayed fatherhood. Schizophr. Bull. 41, 708–714 (2015).

Power, R. A. et al. Fecundity of patients with schizophrenia, autism, bipolar disorder, depression, anorexia nervosa, or substance abuse vs their unaffected siblings. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 70, 22–30 (2013).

Gratten, J. et al. Risk of psychiatric illness from advanced paternal age is not predominantly from de novo mutations. Nat. Genet. 48, 718–724 (2016).

Dempster, E. L. et al. Disease-associated epigenetic changes in monozygotic twins discordant for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Hum. Mol. Genet. 20, 4786–4796 (2011).

Milekic, M. H. et al. Age-related sperm DNA methylation changes are transmitted to offspring and associated with abnormal behavior and dysregulated gene expression. Mol. Psychiatry 20, 995–1001 (2015).

Jenkins, T. G. et al. Methylation alterations: possible implications in offspring disease susceptibility. PLoS Genet. 10, 1004458 (2014).

Lillycrop, K. A., Hoile, S. P., Grenfell, L. & Burdge, G. C. DNA methylation, ageing and the influence of early life nutrition. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 73, 413–421 (2014).

Soubry, A. Epigenetic inheritance and evolution: a paternal perspective on dietary influences. Progr. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 118, 79–85 (2015).

Soubry, A. et al. Paternal obesity is associated with IGF2 hypomethylation in newborns: results from a Newborn Epigenetics Study (NEST) cohort. BMC Med. 11, 29 (2013).

Soubry, A. et al. Newborns of obese parents have altered DNA methylation patterns at imprinted genes. Int. J. Obes. 39, 650–657 (2015).

Feinberg, J. I. et al. Paternal sperm DNA methylation associated with early signs of autism risk in an autism-enriched cohort. Int. J. Epidemiol. 44, 1199–1210 (2015).

Denomme, M. M. et al. Advanced paternal age directly impacts mouse embryonic placental imprinting. PLoS ONE 15, e0229904 (2020).

Van Opstal, J., Fieuws, S., Spiessens, C. & Soubry, A. Male age interferes with embryo growth in IVF treatment. Hum. Reprod. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep/deaa256 (2020).

Sharma, R. et al. Effects of increased paternal age on sperm quality, reproductive outcome and associated epigenetic risks to offspring. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 13, 35 (2015).

Miller, B. et al. Advanced paternal age and parental history of schizophrenia. Schizophr. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2011.08.013 (2011).

Puleo, C. M., Reichenberg, A., Smith, C. J., Kryzak, L. A. & Silverman, J. M. Do autism-related personality traits explain higher paternal age in autism? Mol. Psychiatry 13, 243–244 (2008).

Pinborg, A. et al. Epigenetics and assisted reproductive technologies. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 95, 10–15 (2016).

Nilsen, A. B. V., Waldenström, U., Rasmussen, S., Hjelmstedt, A. & Schytt, E. Characteristics of first-time fathers of advanced age: a Norwegian population-based study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 13, 29 (2013).

Babadagi, Z. et al. Associations between father temperament, character, rearing, psychopathology and child temperament in children aged 3–6 years. Psychiatr. Q. 89, 589–604 (2018).

Fedak, K. M., Bernal, A., Capshaw, Z. A. & Gross, S. Applying the Bradford Hill criteria in the 21st century: How data integration has changed causal inference in molecular epidemiology. Emerg. Themes Epidemiol. 12, 14 (2015).

Rothman, K. J. & Greenland, S. Causation and causal inference in epidemiology. Am. J. Public Health 95, S144–S150 (2005).

Grigoroiu-Serbanescu, M. et al. Paternal age effect on age of onset in bipolar I disorder is mediated by sex and family history. Am. J. Med. Genet. B 159 B, 567–579 (2012).

Kaarouch, I. et al. Paternal age: negative impact on sperm genome decays and IVF outcomes after 40 years. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 85, 271–280 (2018).

Rothman, K. J. Epidemiology: An Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2012).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a research grant from KU Leuven University (OT/14/109).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

I.V. developed the conception and design of this review, acquired the data, and wrote the interpretation to draft the manuscript, C.D. wrote the clinical aspects and relevance of this work and the interpretation of the study designs used. A.S. is the principal investigator who oversaw the conception and design of this review, and who contributed to the discussion and editing of the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and given their approval of submission for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vervoort, I., Delger, C. & Soubry, A. A multifactorial model for the etiology of neuropsychiatric disorders: the role of advanced paternal age. Pediatr Res 91, 757–770 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01435-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-021-01435-4