Abstract

Background

Fetal cardiac output is typically assessed using gestational age (GA) or estimated fetal weight (EFW), but the optimal reference remains unclear due to limited validation.

Methods

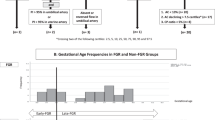

We retrospectively analyzed prospectively collected data from singleton fetuses at 27 + 2 to 29 + 6 weeks of gestation. Subjects included those with small for gestational age (SGA; EFW <10th percentile), large for gestational age (LGA; EFW > 90th percentile), and appropriate for gestational age (AGA), all without structural abnormalities. Associations between fetal cardiac output and both GA and EFW were evaluated using generalized additive models.

Results

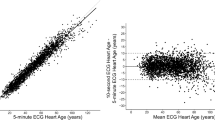

Among 443 fetuses with EFWs ranging from 873 to 1631 g, GA showed no significant association with any cardiac parameter (p ≥ 0.282). In contrast, EFW demonstrated significant and largely linear associations with all parameters (p < 0.001, F ≥ 16.7), consistent across GA and EFW ranges. Cardiac parameter distributions by EFW were similar across AGA, SGA, and LGA groups.

Conclusion

EFW showed stronger and more consistent correlations with fetal cardiac parameters than GA, supporting its use as a more reliable reference for fetal cardiac evaluation across different growth statuses.

Impact

-

Fetal cardiac output is typically assessed using reference ranges based on either gestational age (GA) or estimated fetal weight (EFW), both derived from appropriate for gestational age (AGA) fetuses.

-

We showed that EFW is superior to GA for fetal cardiac evaluation.

-

Including non-AGA fetuses confirmed they can be assessed similarly to AGA fetuses.

-

The new EFW-based reference ranges offer a uniform standard, enabling more definitive assessments across varied fetal growth.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 14 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $18.50 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data underlying this article will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

Dewey, F. E., Rosenthal, D., Murphy, D. J., Froelicher, V. F. & Ashley, E. A. Does size matter?. Circulation 117, 2279–2287 (2008).

Eriksen-Volnes, T. et al. Normalized echocardiographic values from guideline-directed dedicated views for cardiac dimensions and left ventricular function. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 16, 1501–1515 (2023).

Strom, J. B. et al. Reference values for indexed echocardiographic chamber sizes in older adults: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 13, e034029 (2024).

Olivieri, L. J. et al. Normal right and left ventricular volumes prospectively obtained from cardiovascular magnetic resonance in awake, healthy, 0-12 year old children. J. Cardiovasc. Magn. Reson. 22, 11 (2020).

Mielke, G. & Benda, N. Cardiac output and central distribution of blood flow in the human fetus. Circulation 103, 1662–1668 (2001).

Mao, Y. K. et al. Z-score reference ranges for pulsed-wave Doppler indices of the cardiac outflow tracts in normal fetuses. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 35, 811–825 (2019).

Rocha, L. A., Rolo, L. C., Nardozza, L. M. M., Tonni, G. & Araujo Junior, E. Z-score reference ranges for fetal heart functional measurements in a large Brazilian pregnant women sample. Pediatr. Cardiol. 40, 554–562 (2019).

Vigneswaran, T. V. et al. Reference ranges for the size of the fetal cardiac outflow tracts from 13 to 36 weeks gestation: a single-center study of over 7000 cases. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 11, e007575 (2018).

Rudolph, A. M. Distribution and regulation of blood flow in the fetal and neonatal lamb. Circ. Res. 57, 811–821 (1985).

Rasanen, J., Wood, D. C., Weiner, S., Ludomirski, A. & Huhta, J. C. Role of the pulmonary circulation in the distribution of human fetal cardiac output during the second half of pregnancy. Circulation 94, 1068–1073 (1996).

Kiserud, T., Ebbing, C., Kessler, J. & Rasmussen, S. Fetal cardiac output, distribution to the placenta and impact of placental compromise. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 28, 126–136 (2006).

Sutton, M. S., Groves, A., MacNeill, A., Sharland, G. & Allan, L. Assessment of changes in blood flow through the lungs and foramen ovale in the normal human fetus with gestational age: a prospective Doppler echocardiographic study. Br. Heart J. 71, 232–237 (1994).

Sutton, M. G. S. J., Plappert, T. & Doubilet, P. Relationship between placental blood flow and combined ventricular output with gestational age in normal human fetus. Cardiovasc. Res. 25, 603–608 (1991).

Hadlock, F. P., Deter, R. L., Harrist, R. B. & Park, S. K. Estimating fetal age: computer-assisted analysis of multiple fetal growth parameters. Radiology 152, 497–501 (1984).

Itabashi, K., Miura, F., Uehara, R. & Nakamura, Y. New Japanese neonatal anthropometric charts for gestational age at birth. Pediatr. Int 56, 702–708 (2014).

Smrcek, J. M. et al. Detection rate of early fetal echocardiography and in utero development of congenital heart defects. J. Ultrasound Med. 25, 187–196 (2006).

Satomi, G. Guidelines for fetal echocardiography. Pediatr. Int. 57, 1–21 (2015).

Carvalho, J. et al. Isuog practice guidelines (updated): fetal cardiac screening. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 61, 788–803 (2023).

van Nisselrooij, A. E. L. et al. Why are congenital heart defects being missed?. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 55, 747–757 (2020).

Sun, H. Y., Proudfoot, J. A. & McCandless, R. T. Prenatal detection of critical cardiac outflow tract anomalies remains suboptimal despite revised obstetrical imaging guidelines. Congenit. heart Dis. 13, 748–756 (2018).

Lytzen, R. et al. Live-born major congenital heart disease in denmark: incidence, detection rate, and termination of pregnancy rate from 1996 to 2013. JAMA Cardiol. 3, 829–837 (2018).

Kirk, J. S. et al. Sonographic screening to detect fetal cardiac anomalies: a 5-year experience with 111 abnormal cases. Obstet. Gynecol. 89, 227–232 (1997).

Moon-Grady, A. J. et al. Guidelines and recommendations for performance of the fetal echocardiogram: an update from the american society of echocardiography. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 36, 679–723 (2023).

Anandakumar, C. et al. Early asymmetric iugr and aneuploidy. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 22, 365–370 (1996).

Dall’Asta, A. et al. Etiology and perinatal outcome of periviable fetal growth restriction associated with structural or genetic anomaly. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 55, 368–374 (2020).

Langer, O. Fetal macrosomia: etiologic factors. Clin. Obstet. Gynecol. 43, 283–297 (2000).

Carvalho, J. S. et al. Isuog Practice Guidelines (Updated): Sonographic Screening Examination of the Fetal Heart. (2013).

Luewan, S. et al. Z Score reference ranges of fetal cardiac output from 12 to 40 weeks of pregnancy. J. Ultrasound Med. 39, 515–527 (2020).

Hatle, L. Doppler Ultrasound in Cardiology. Physical Principles and Clinical Applications, 77–89 (1982).

Arduini, D., Rizzo, G. & Romanini, C. Fetal cardiac output measurements in normal and pathologic states. 271–280 (Raven Press, 1995).

Shinozuka, N. Ellipse tracing fetal growth assessment using abdominal circumference: JSUM standardization committee for fetal measurements. J. Med. Ultrasound 8, 87–94 (2000).

Lausman, A., Kingdom, J. & Maternal Fetal Medicine, C. Intrauterine growth restriction: screening, diagnosis, and management. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 35, 741–748 (2013).

Salomon, L. J. et al. Isuog practice guidelines: ultrasound assessment of fetal biometry and growth. Ultrasound Obstet. Gynecol. 53, 715–723 (2019).

Zuur, A. F., Ieno, E. N., Walker, N. J., Saveliev, A. A. & Smith, G. M. Mixed Effects Models and Extensions in Ecology with R Vol. 574 (Springer, 2009).

Vuong, Q.-H. et al. Bayesian analysis for social data: a step-by-step protocol and interpretation. MethodsX 7, 100924 (2020).

Brooks, S., Gelman, A., Jones, G. & Meng, X.-L. Handbook of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (CRC Press, 2011).

Vats, D., Flegal, J. M. & Jones, G. L. Multivariate output analysis for Markov chain Monte Carlo. Biometrika 106, 321–337 (2019).

McElreath, R. Statistical Rethinking: A Bayesian Course with Examples in R and Stan (Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018).

Lynch, S. M. Introduction to Applied Bayesian Statistics and Estimation for Social Scientists, 1 (Springer, 2007).

Verburg, B. O. et al. Fetal hemodynamic adaptive changes related to intrauterine growth: the Generation R Study. Circulation 117, 649–659 (2008).

Itakura, A. et al. Guidelines for obstetrical practice in Japan: Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Japan Association of Obstetricians and Gynecologists 2020 edition. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 49, 5–53 (2023).

Acknowledgements

During the preparation of this study the authors used ChatGPT4 and DeepL for translational and academic editing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Sho Tano: conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article. Tatsuwo Inamura, Mina Kato, and Manami Ito: conception and design of the study, acquisition of data review and editing. Takehiko Takeda: acquisition of data review and editing. Fumie Kinoshita: data analysis. Kazuya Fuma, Seiko Matsuo, Takafumi Ushida, and Kenji Imai: review and editing. Hiroaki Kajiyama and Tomomi Kotani: revising the article critically for important intellectual content. Yasuyuki Kishigami and Hidenori Oguchi: conception and design of the study, and revising the article critically for important intellectual content.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tano, S., Inamura, T., Kato, M. et al. Estimated fetal weight or gestational age: which is crucial for fetal cardiac evaluation?. Pediatr Res (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04584-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-025-04584-y