Abstract

Study design

This was an animal study.

Objectives

Local inflammation is attenuated below high thoracic SCI, where innervation of major lymphoid organs is involved. However, whether inflammatory responses are affected after low thoracic SCI, remains undetermined. The aim of this study was to characterize the influence of low thoracic SCI on carrageenan-induced paw swelling in intact and paralyzed limbs, at acute and subacute stages.

Setting

University and hospital-based research center, Mexico City, Mexico.

Methods

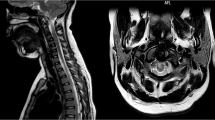

Rats received a severe contusive SCI at T9 spinal level or sham injury. Then, 1 and 15 days after lesion, carrageenan or vehicle was subcutaneously injected in forelimb and hindlimb paws. Paw swelling was measured over a 6-h period using a plethysmometer.

Results

Swelling increased progressively reaching the maximum 6 h post-carrageenan injection. Swelling increase in sham-injured rats was approximately 130% and 70% compared with baseline values of forelimbs and hindlimbs, respectively. Paws injected with saline exhibited no measurable swelling. Carrageenan-induced paw swelling 1-day post-SCI was suppressed in both intact and paralyzed limbs. Fifteen days post-injury, the swelling response to carrageenan was completely reestablished in forelimbs, whereas in hindlimbs it remained significantly attenuated compared with sham-injured rats.

Conclusions

SCI at low spinal level affects the induced swelling response in a different way depending on both, the neurological status of challenged regions and the stage of injury. These findings suggest that neurological compromise of the main immunological organs is not a prerequisite for the local swelling response to be affected after injury.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Guizar-Sahagun G, Castaneda-Hernandez G, Garcia-Lopez P, Franco-Bourland R, Grijalva I, Madrazo I. Pathophysiological mechanisms involved in systemic and metabolic alterations secondary to spinal cord injury. Proc West Pharmacol Soc. 1998;41:237–40.

Guizar-Sahagun G, Velasco-Hernandez L, Martinez-Cruz A, Castaneda-Hernandez G, Bravo G, Rojas G, et al. Systemic microcirculation after complete high and low thoracic spinal cord section in rats. J Neurotrauma. 2004;21:1614–23.

Sun X, Jones ZB, Chen XM, Zhou L, So KF, Ren Y. Multiple organ dysfunction and systemic inflammation after spinal cord injury: a complex relationship. J Neuroinflamm. 2016;13:260.

Riegger T, Conrad S, Liu K, Schluesener HJ, Adibzahdeh M, Schwab JM. Spinal cord injury-induced immune depression syndrome (SCI-IDS). Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:1743–7.

Cotton BA, Pryor JP, Chinwalla I, Wiebe DJ, Reilly PM, Schwab CW. Respiratory complications and mortality risk associated with thoracic spine injury. J Trauma. 2005;59:1400–7.

Brommer B, Engel O, Kopp MA, Watzlawick R, Muller S, Pruss H, et al. Spinal cord injury-induced immune deficiency syndrome enhances infection susceptibility dependent on lesion level. Brain. 2016;139:692–707.

Gris D, Hamilton EF, Weaver LC. The systemic inflammatory response after spinal cord injury damages lungs and kidneys. Exp Neurol. 2008;211:259–70.

Basbaum AI, Levine JD. The contribution of the nervous system to inflammation and inflammatory disease. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1991;69:647–51.

Lin Q, Wu J, Willis WD. Dorsal root reflexes and cutaneous neurogenic inflammation after intradermal injection of capsaicin in rats. J Neurophysiol. 1999;82:2602–11.

Chiu IM, von Hehn CA, Woolf CJ. Neurogenic inflammation and the peripheral nervous system in host defense and immunopathology. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1063–7.

Backhaus M, Citak M, Tilkorn DJ, Meindl R, Schildhauer TA, Fehmer T. Pressure sores significantly increase the risk of developing a Fournier’s gangrene in patients with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:1143–6.

Marbourg JM, Bratasz A, Mo X, Popovich PG. Spinal cord injury suppresses cutaneous inflammation: implications for peripheral wound healing. J Neurotrauma. 2017;34:1149–55.

Reinke JM, Sorg H. Wound repair and regeneration. Eur Surg Res. 2012;49:35–43.

Macneil BJ, Nance DM. Skin inflammation and immunity after spinal cord injury. Neuroimmune Biol. 2001;1:459–73.

Young W. MASCIS spinal cord contusion model. In: Chen J, Xu ZC, Xu XM, Zhang JH, editors. Animal models of acute neurological injuries.. Totowa, NJ, USA: Humana Press; 2009. p. 411–21.

Posadas I, Bucci M, Roviezzo F, Rossi A, Parente L, Sautebin L, et al. Carrageenan-induced mouse paw oedema is biphasic, age-weight dependent and displays differential nitric oxide cyclooxygenase-2 expression. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:331–8.

Ditunno J, Little J, Tessler A, Burns A. Spinal shock revisited: a four-phase model. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:383–95.

Morris CJ. Carrageenan-induced paw edema in the rat and mouse. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;225:115–21.

Annamalai P, Thangam EB. Local and systemic profiles of inflammatory cytokines in carrageenan-induced paw inflammation in rats. Immunol Invest. 2017;46:274–83.

Willis WD Jr.. Dorsal root potentials and dorsal root reflexes: a double-edged sword. Exp Brain Res. 1999;124:395–421.

Valencia-de Ita S, Lawand NB, Lin Q, Castaneda-Hernandez G, Willis WD. Role of the Na+-K+-2Cl- cotransporter in the development of capsaicin-induced neurogenic inflammation. J Neurophysiol. 2006;95:3553–61.

Granger DN, Senchenkova E (eds). Inflammation and the microcirculation. In: Colloquium series on integrated systems physiology: from molecule to function. Morgan & ClaypoolLife Sciences; San Rafael, CA, USA 2010. p. 1-87.

Lucin KM, Sanders VM, Jones TB, Malarkey WB, Popovich PG. Impaired antibody synthesis after spinal cord injury is level dependent and is due to sympathetic nervous system dysregulation. Exp Neurol. 2007;207:75–84.

Lotz M, Vaughan JH, Carson DA. Effect of neuropeptides on production of inflammatory cytokines by human monocytes. Science. 1988;241:1218–21.

Deruddre S, Combettes E, Estebe JP, Duranteau J, Benhamou D, Beloeil H, et al. Effects of a bupivacaine nerve block on the axonal transport of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) in a rat model of carrageenan-induced inflammation. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:652–9.

Frisbie JH. Microvascular instability in tetraplegic patients: preliminary observations. Spinal Cord. 2004;42:290–3.

West C, Alyahya A, Laher I, Krassioukov A. Peripheral vascular function in spinal cord injury: a systematic review. Spinal Cord. 2013;51:10–19.

Phillips A, Matin N, Frias B, Zheng M, Jia M, West C, et al. Rigid and remodelled: cerebrovascular structure and function after experimental high‐thoracic spinal cord transection. J Physiol. 2016;594:1677–88.

Mignini F, Streccioni V, Amenta F. Autonomic innervation of immune organs and neuroimmune modulation. Auton Autacoid Pharmacol. 2003;23:1–25.

Zhang Y, Guan Z, Reader B, Shawler T, Mandrekar-Colucci S, Huang K, et al. Autonomic dysreflexia causes chronic immune suppression after spinal cord injury. J Neurosci. 2013;33:12970–81.

Acknowledgements

We thank Angelina Martinez-Cruz for her invaluable technical assistance with spine surgery.

Funding

AR-C received a fellowship grant (number 378379) from the National Council for Science and Technology (CONACYT, http://www.conacyt.mx/pci/index.php) to support her doctoral studies.

Author contributions

AR-C was responsible for design of methodology, writing the protocol, performing the experimental procedures, collecting and analyzing data, interpreting results, and writing original draft. LC-A was responsible for design of methodology, management and coordination of research activity, planning, and execution, as well as analysis and interpretation of data. GC-H was responsible for conception and design of the study, providing study materials, animals, and analysis tools, analysis and interpretation of data, writing original draft, and presentation of the critically revised work. LF-P was responsible for oversight and leadership the research activity planning and execution, including mentorship external to the core team, and analysis and interpretation of data. GG-S was responsible for conception and design of the study, review of the protocol, analysis and interpretation of data, writing original draft, and presentation of the critically revised work. All authors revised and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Cal y Mayor, A., Cruz-Antonio, L., Castañeda-Hernández, G. et al. Time-dependent changes in paw carrageenan-induced inflammation above and below the level of low thoracic spinal cord injury in rats. Spinal Cord 56, 964–970 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0144-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-018-0144-5

This article is cited by

-

Pharmacokinetics and anti-inflammatory effect of naproxen in rats with acute and subacute spinal cord injury

Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Archives of Pharmacology (2020)