Abstract

Study design

Cross-sectional study

Objective

To evaluate alternative scoring approaches for the modified Spinal Cord Injury Secondary Conditions Scale (SCI-SCS) using severity- and mortality-based weights, and to examine their associations with functioning and self-reported health in individuals with SCI.

Setting

Community

Methods

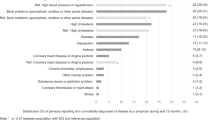

We analyzed data from 10,347 participants in the International Spinal Cord Injury Survey (InSCI). Eight scoring approaches were constructed from 14 secondary health conditions and a depression item, varying by severity coding and by whether mortality weights were applied equally or condition-specifically. Associations with functioning (ICF-based composite score) and self-reported health were assessed using Pearson and Spearman correlations, with additional country-level analyses to explore variability.

Results

All scoring approaches were negatively correlated with both outcomes, indicating that higher secondary health condition burden was associated with worse functioning and poorer health. The score combining the modified SCI-SCS with condition-specific mortality weights showed the highest correlations, though differences from the unweighted score were small. Both scores demonstrated moderate associations with the outcomes. Country-level analyses revealed variability, partly related to sample size, but overall patterns were consistent.

Conclusion

The modified SCI-SCS demonstrated moderate and robust associations with functioning and self-reported health, supporting its use as a pragmatic proxy of overall health status in individuals with SCI. Weighting by mortality risks yielded only marginal gains, suggesting that the unweighted score remains a suitable option for research and practice. These findings advance the use of self-reported measures to capture health burden in SCI and encourage further validation with independent outcomes and across diverse contexts.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the International Spinal Cord Injury Community Survey (InSCI) Study Center, but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are however available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of the InSCI Study Center. To request the data please contact ana.ona@paraplegie.ch.

References

World Health Organization, International Spinal Cord Society. International perspectives on spinal cord injury: World Health Organization; 2013.

Brinkhof MW, Al-Khodairy A, Eriks-Hoogland I, Fekete C, Hinrichs T, Hund-Georgiadis M, et al. Health conditions in people with spinal cord injury: Contemporary evidence from a population-based community survey in Switzerland. J Rehabil Med. 2016;48:197–209.

Strøm V, Månum G, Arora M, Joseph C, Kyriakides A, OSTERTHUN R, et al. Physical health conditions in persons with spinal cord injury across 21 countries worldwide. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2022;54:jrm00302.

Cao Y, DiPiro N, Krause JS. Health factors and spinal cord injury: a prospective study of risk of cause-specific mortality. Spinal Cord. 2019;57:594–602.

Valderas JM, Starfield B, Sibbald B, Salisbury C, Roland M. Defining comorbidity: implications for understanding health and health services. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2009;7:357–63.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1987;40:373–83.

Seekins T, Smith N, McCleary T, Clay J, Walsh J. Secondary disability prevention: Involving consumers in the development of a public health surveillance instrument. Journal of Disability Policy Studies. 1990;1:21–36.

Sangha O, Stucki G, Liang MH, Fossel AH, Katz JN. The self‐administered comorbidity questionnaire: a new method to assess comorbidity for clinical and health services research. Arthritis Care & Research: Official Journal of the American College of Rheumatology. 2003;49:156–63.

Aubert CE, Fankhauser N, Marques-Vidal P, Stirnemann J, Aujesky D, Limacher A, et al. Multimorbidity and healthcare resource utilization in Switzerland: a multicentre cohort study. BMC health services research. 2019;19:1–9.

Buddeke J, Bots ML, van Dis I, Visseren FL, Hollander M, Schellevis FG, et al. Comorbidity in patients with cardiovascular disease in primary care: a cohort study with routine healthcare data. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69:e398–e406.

Seekins T, Ravesloot C. Secondary conditions experienced by adults with injury-related disabilities in Montana. Topics in Spinal Cord Injury Rehabilitation. 2000;6:43–53.

Kalpakjian CZ, Scelza WM, Forchheimer MB, Toussaint LL. Preliminary reliability and validity of a spinal cord injury secondary conditions scale. The journal of spinal cord medicine. 2007;30:131–9.

Arora M, Harvey L, Lavrencic L, Bowden J, Nier L, Glinsky J, et al. A telephone-based version of the spinal cord injury–secondary conditions scale: a reliability and validity study. Spinal Cord. 2016;54:402–5.

Stucki G, Bickenbach J. The international spinal cord injury survey and the learning health system for spinal cord injury. American journal of physical medicine & rehabilitation. 2017;96:S2–S4.

Stucki G, Bickenbach J. The implementation challenge and the learning health system for SCI initiative. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:S55–S60.

Cieza A. The international spinal cord injury survey and the learning health system for spinal cord injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:S1.

Gross-Hemmi MH, Post MW, Ehrmann C, Fekete C, Hasnan N, Middleton JW, et al. Study protocol of the international spinal cord injury (InSCI) community survey. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:S23–S34.

Fekete C, Brach M, Ehrmann C, Post MW, Stucki G. Cohort profile of the international spinal cord injury (InSCI) community survey implemented in 22 countries. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2020;101:2103–11.

Fekete C, Post MW, Bickenbach J, Middleton J, Prodinger B, Selb M, et al. A structured approach to capture the lived experience of spinal cord injury: data model and questionnaire of the international spinal cord injury community survey. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96:S5–S16.

Fekete C, Gurtner B, Simon K, Gemperli A, Gmünder HP, Hund-Georgiadis M, et al. Inception cohort of the swiss spinal cord injury cohort study (SwiSCI): design, participant characteristics, response rates and non-response. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2021;53:jrm00159.

Post MW, Brinkhof MW, von, Elm E, Boldt C, Brach M, et al. Design of the Swiss spinal cord injury cohort study. American Journal of Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation. 2011;90:S5–S16.

Krause JS, Cao Y, DeVivo MJ, DiPiro ND. Risk and protective factors for cause-specific mortality after spinal cord injury. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2016;97:1669–78.

Sabariego C, Ehrmann C, Bickenbach J, Pacheco Barzallo D, Schedin Leiulfsrud A, Strøm V, et al. Ageing, functioning patterns and their environmental determinants in the spinal cord injury (sci) population: a comparative analysis across eleven european countries implementing the international spinal cord injury community survey. Plos one. 2023;18:e0284420.

Lorem G, Cook S, Leon DA, Emaus N, Schirmer H. Self-reported health as a predictor of mortality: A cohort study of its relation to other health measurements and observation time. Scientific Reports. 2020;10:4886.

Chamberlain JD, Meier S, Mader L, von Groote PM, Brinkhof MW. Mortality and longevity after a spinal cord injury: systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;44:182–98.

Fekete C, Debnar C, Scheel-Sailer A, Gemperli A. Does the socioeconomic status predict health service utilization in persons with enhanced health care needs? Results from a population-based survey in persons with spinal cord lesions from Switzerland. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21:94.

Pacheco Barzallo D, Gross-Hemmi M, Bickenbach J, Juocevičius A, Popa D, Wahyuni LK, et al. Quality of life and the health system: a 22-country comparison of the situation of people with spinal cord injury. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2020;101:2167–76.

Barzallo DP, Gross-Hemmi M, Bickenbach J, Juocevičius A, Popa D, Wahyuni LK, et al. Quality of life and the health system: a 22-country comparison of the situation of people with spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2020;101:2167–76.

Acknowledgements

This study is based on data from the International Spinal Cord Injury (InSCI) Community Survey (Ref. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2017;96[suppl]: S23-S34). The members of the InSCI Steering Committee are J. Middleton, J. Patrick Engkasan, G. Stucki, M. Brach, J. Bickenbach, M. Gross-Hemmi, C. Thyrian, L. Battistella, J. Li, B. Perrouin-Verbe, C. Gutenbrunner, C. Rapidi, L.K. Wahyuni, M. Zampolini, E. Saitoh, B.S. Lee, A. Juocevicius, N. Hasnan, A. Hajjioui, M.W.M. Post, V Strøm, P. Tederko, D. Popa, C. Joseph, M. Avellanet, M. Baumberger, A. Kovindha, and R. Escorpizo.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 801076, through the SSPH n Global PhD Fellowship Programme in Public Health Sciences (GlobalP3HS) of the Swiss School of Public Health.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AO and DP were involved in the conceptualization and formal analysis of the study. AO performed the statistical analysis and wrote the original draft. DP reviewed and approved the methodology. DP, VS, CS, and AG critically reviewed and interpreted the results. All the authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

Authors must declare whether or not there are any competing financial interests in relation to the work described.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval and consent to participate are not required for this study. The InSCI Study Group ensures that all the research teams from the participant countries follow international standards for ethical approval and obtain consent to participate in each country. In addition, all the data from the International Spinal Cord Injury Survey (InSCI) are anonymized, and all research bases on data from this community survey, including the present study, need to be evaluated and approved before obtaining the data.

Consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the InSCI Study Group protocol for best practices in cross-cultural surveys.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Oña, A., Strøm, V., Sabariego, C. et al. Evaluating the modified spinal cord injury secondary conditions scale (SCI-SCS) combining severity and mortality-based weights. Spinal Cord (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-026-01167-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41393-026-01167-4