Abstract

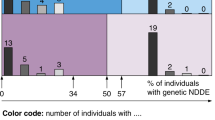

Syndromes caused by copy number variations are described as reciprocal when they result from deletions or duplications of the same chromosomal region. When comparing the phenotypes of these syndromes, various clinical features could be described as reversed, probably due to the opposite effect of these imbalances on the expression of genes located at this locus. The NFIX gene codes for a transcription factor implicated in neurogenesis and chondrocyte differentiation. Microdeletions and loss of function variants of NFIX are responsible for Sotos syndrome-2 (also described as Malan syndrome), a syndromic form of intellectual disability associated with overgrowth and macrocephaly. Here, we report a cohort of nine patients harboring microduplications encompassing NFIX. These patients exhibit variable intellectual disability, short stature and small head circumference, which can be described as a reversed Sotos syndrome-2 phenotype. Strikingly, such a reversed phenotype has already been described in patients harboring microduplications encompassing NSD1, the gene whose deletions and loss-of-function variants are responsible for classical Sotos syndrome. Even though the type/contre-type concept has been criticized, this model seems to give a plausible explanation for the pathogenicity of 19p13 microduplications, and the common phenotype observed in our cohort.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Miller DT, Adam MP, Aradhya S, et al. Consensus statement: chromosomal microarray is a first-tier clinical diagnostic test for individuals with developmental disabilities or congenital anomalies. Am J Hum Genet 2010;86:749–64.

Redon R, Ishikawa S, Fitch KR, et al. Global variation in copy number in the human genome. Nature 2006;444:444–54.

Zarrei M, MacDonald JR, Merico D, Scherer SW. A copy number variation map of the human genome. Nat Rev Genet 2015;16:172–83.

Franke M, Ibrahim DM, Andrey G, et al. Formation of new chromatin domains determines pathogenicity of genomic duplications. Nature 2016;538:265–9.

Liu P, Carvalho CM, Hastings P, Lupski JR. Mechanisms for recurrent and complex human genomic rearrangements. Curr Opin Genet Dev 2012;22:211–20.

Jacquemont S, Reymond A, Zufferey F, et al. Mirror extreme BMI phenotypes associated with gene dosage at the chromosome 16p11.2 locus. Nature 2011;478:97–102.

Sotos JF. Sotos syndrome 1 and 2. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 2014;12:2–16.

Malan V, Rajan D, Thomas S, et al. Distinct effects of allelic NFIX mutations on nonsense-mediated mRNA decay engender either a Sotos-like or a Marshall-Smith syndrome. Am J Hum Genet 2010;87:189–98.

Firth HV, Richards SM, Bevan AP, et al. DECIPHER: Database of Chromosomal Imbalance and Phenotype in Humans Using Ensembl Resources. Am J Hum Genet 2009;84:524–33.

Dolan M, Mendelsohn NJ, Pierpont ME, Schimmenti LA, Berry SA, Hirsch B. A novel microdeletion/microduplication syndrome of 19p13.13. Genet Med 2010;12:503–11.

Kent WJ, Sugnet CW, Furey TS, et al. The Human Genome Browser at UCSC. Genome Res 2002;12:996–1006.

Singleton BK, Burton NM, Green C, Brady RL, Anstee DJ. Mutations in EKLF/KLF1 form the molecular basis of the rare blood group In(Lu) phenotype. Blood 2008;112:2081–88.

Goodman SI, Stein DE, Schlesinger S, et al. Glutaryl-CoA dehydrogenase mutations in glutaric acidemia (type I): review and report of thirty novel mutations. Hum Mutat 1998;12:141–4.

Nangalia J, Massie CE, Baxter EJ, et al. Somatic CALR mutations in myeloproliferative neoplasms with nonmutated JAK2. N Engl J Med 2013;369:2391–405.

Kordasiewicz HB, Thompson RM, Clark HB, Gomez CM. C-termini of P/Q-type Ca2+ channel alpha1A subunits translocate to nuclei and promote polyglutamine-mediated toxicity. Hum Mol Genet 2006;15:1587–99.

Ophoff RA, Terwindt GM, Vergouwe MN, et al. Familial hemiplegic migraine and episodic ataxia type-2 are caused by mutations in the Ca2+ channel gene CACNL1A4. Cell 1996;87:543–52.

Labrum RW, Rajakulendran S, Graves TD, et al. Large scale calcium channel gene rearrangements in episodic ataxia and hemiplegic migraine: implications for diagnostic testing. J Med Genet 2009;46:786–91.

Chioza B, Wilkie H, Nashef L, et al. Association between the alpha(1a) calcium channel gene CACNA1A and idiopathic generalized epilepsy. Neurology 2001;56:1245–6.

Myers C, McMahon J, Schneider A, et al. De novo mutations in SLC1A2 and CACNA1A are important causes of epileptic encephalopathies. Am J Hum Genet 2016;99:287–98.

Zhuchenko O, Bailey J, Bonnen P, et al. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (SCA6) associated with small polyglutamine expansions in the α1A-voltage-dependent calcium channel. Nat Genet 1997;15:62–9.

Schoch K, Meng L, Szelinger S, et al. A recurrent de novo variant in NACC1 causes a syndrome characterized by infantile epilepsy, cataracts, and profound developmental delay. Am J Hum Genet 2017;100:343–51.

Roulet E, Bucher P, Schneider R, et al. Experimental analysis and computer prediction of CTF/NFI transcription factor DNA binding sites. J Mol Biol 2000;297:833–48.

Deneen B, Ho R, Lukaszewicz A, Hochstim CJ, Gronostajski RM, Anderson DJ. The transcription factor NFIA controls the onset of gliogenesis in the developing spinal cord. Neuron 2006;52:953–68.

Kang P, Lee HK, Glasgow SM, et al. Sox9 and NFIA coordinate a transcriptional regulatory cascade during the initiation of gliogenesis. Neuron 2012;74:79–94.

Wilczynska KM, Singh SK, Adams B, et al. Nuclear factor I isoforms regulate gene expression during the differentiation of human neural progenitors to astrocytes. Stem Cells 2009;27:1173–81.

das Neves L, Duchala CS, Tolentino-Silva F, et al. Disruption of the murine nuclear factor I-A gene (Nfia) results in perinatal lethality, hydrocephalus, and agenesis of the corpus callosum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999;96:11946–51.

Shu T, Butz KG, Plachez C, Gronostajski RM, Richards LJ. Abnormal development of forebrain midline glia and commissural projections in Nfia knock-out mice. J Neurosci 2003;23:203–12.

Piper M, Moldrich RX, Lindwall C, et al. Multiple non-cell-autonomous defects underlie neocortical callosal dysgenesis in Nfib-deficient mice. Neural Dev 2009;4:43.

Driller K, Pagenstecher A, Uhl M, et al. Nuclear factor I X deficiency causes brain malformation and severe skeletal defects. Mol Cell Biol 2007;27:3855–67.

Campbell CE, Piper M, Plachez C, et al. The transcription factor Nfix is essential for normal brain development. BMC Dev Biol 2008;8:52.

Heng YHE, Zhou B, Harris L, et al. NFIX regulates proliferation and migration within the murine SVZ neurogenic niche. Cereb Cortex 2015;25:3758–78.

Vidovic D, Harris L, Harvey TJ, et al. Expansion of the lateral ventricles and ependymal deficits underlie the hydrocephalus evident in mice lacking the transcription factor NFIX. Brain Res 2015;1616:71–87.

Martynoga B, Mateo JL, Zhou B, et al. Epigenomic enhancer annotation reveals a key role for NFIX in neural stem cell quiescence. Genes Dev 2013;27:1769–86.

Zhou B, Osinski JM, Mateo JL, et al. Loss of NFIX transcription factor biases postnatal neural stem/progenitor cells toward oligodendrogenesis. Stem Cells Dev 2015;24:2114–26.

Holmfeldt P, Pardieck J, Saulsberry AC, et al. Nfix is a novel regulator of murine hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell survival. Blood 2013;122:2987–96.

Rossi G, Antonini S, Bonfanti C, et al. Nfix regulates temporal progression of muscle regeneration through modulation of myostatin expression. Cell Rep 2016;14:2238–49.

Schanze D, Neubauer D, Cormier-Daire V, et al. Deletions in the 3’ part of the NFIX gene including a recurrent Alu-mediated deletion of exon 6 and 7 account for previously unexplained cases of Marshall-Smith syndrome. Hum Mutat 2014;35:1092–100.

Martinez F, Marín-Reina P, Sanchis-Calvo A, et al. Novel mutations of NFIX gene causing Marshall-Smith syndrome or Sotos-like syndrome: one gene, two phenotypes. Pediatr Res 2015;78:533–39.

Priolo M, Grosso E, Mammì C, et al. A peculiar mutation in the DNA-binding/dimerization domain of NFIX causes Sotos-like overgrowth syndrome: a new case. Gene 2012;511:103–5.

Yoneda Y, Saitsu H, Touyama M,et al. Missense mutations in the DNA-binding/dimerization domain of NFIX cause Sotos-like features. J Hum Genet 2012;57:207–11.

Shimojima K, Okamoto N, Tamasaki A, Sangu N, Shimada S, Yamamoto T. An association of 19p13.2 microdeletions with Malan syndrome and Chiari malformation. Am J Med Genet A 2015;167A:724–30.

Klaassens M, Morrogh D, Rosser EM, et al. Malan syndrome: Sotos-like overgrowth with de novo NFIX sequence variants and deletions in six new patients and a review of the literature. Eur J Hum Genet 2015;23:610–15.

Gurrieri F, Cavaliere ML, Wischmeijer A, et al. NFIX mutations affecting the DNA-binding domain cause a peculiar overgrowth syndrome (Malan syndrome): a new patients series. Eur J Med Genet 2015;58:488–91.

Zhang H, Lu X, Beasley J,et al. Reversed clinical phenotype due to a microduplication of Sotos syndrome region detected by array CGH: Microcephaly, developmental delay and delayed bone age. Am J Med Genet A 2011;155:1374–78.

Rosenfeld JA, Kim KH, Angle B, et al. Further evidence of contrasting phenotypes caused by reciprocal deletions and duplications: duplication of NSD1 causes growth retardation and microcephaly. Mol Syndromol 2013;3:247–254

Novara F, Stanzial F, Rossi E, et al. Defining the phenotype associated with microduplication reciprocal to Sotos syndrome microdeletion. Am J Med Genet A 2014;164A:2084–90.

Møller RS, Jensen LR, Maas SM, et al. X-linked congenital ptosis and associated intellectual disability, short stature, microcephaly, cleft palate, digital and genital abnormalities define novel Xq25q26 duplication syndrome. Hum Genet 2014;133:625–38.

Dikow N, Maas B, Gaspar H, et al. The phenotypic spectrum of duplication 5q35.2-q35.3 encompassing NSD1: Is it really a reversed sotos syndrome? Am J Med Genet A 2013;; 161:2158–66.

Nebel RA, Kirschen J, Cai J, Woo YJ, Cherian K, Abrahams BS. Reciprocal relationship between head size, an autism endophenotype, and gene dosage at 19p13.12 points to AKAP8 and AKAP8L. PLOS ONE 2015;10:e0129270.

Nimmakayalu M, Horton VK, Darbro B, et al. Apparent germline mosaicism for a novel 19p13.13 deletion disrupting NFIX and CACNA1A. Am J Med Genet A 2013;161:1105–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their families for participating in this study. We thank Wallid Deb from Universitary Hospital of Nantes for additional data supply, Dr Lucile Pinson and Dr Anouck Schneider from Universitary Hospital of Montpelier and Hilde van Esch from KU Leuven for the constructive discussions about their patients. This study makes use of data generated by the DECIPHER community. A full list of centers who contributed to the generation of the data is available from http://decipher.sanger.ac.uk and via email from decipher@sanger.ac.uk. Funding for this project was provided by the Wellcome Trust. We thank Arthur Sorlin, Dr Julia Lauer Zillhardt and Pr Damien Sanlaville for their help during the use of this database.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Trimouille, A., Houcinat, N., Vuillaume, ML. et al. 19p13 microduplications encompassing NFIX are responsible for intellectual disability, short stature and small head circumference. Eur J Hum Genet 26, 85–93 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-017-0037-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-017-0037-7