Abstract

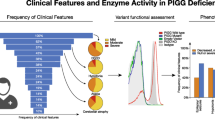

PIGC encodes a protein essential for the biosynthesis of glycophosphatidylinositol-anchored proteins (GPI-APs). So far, three families with biallelic PIGC variants have been reported to exhibit developmental delay/intellectual disability and seizures. Our aim was to further elucidate the clinical and biomolecular characteristics of PIGC pathogenic or likely pathogenic variants. We established a cohort of 18 previously unreported probands. Clinical data were collected, and causative variants were identified though genome/exome sequencing. Variants were modelled in silico using AlphaFold2. Flow cytometry was performed to analyze the cell-surface expression of GPI-APs. The probands displayed a severe neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by developmental and cognitive impairment, early-onset and treatment-resistant seizures, and premature death affecting 10 out of 18 individuals (median age of 40 months, ranging from 40 days to 7 years). Additional features included brain imaging abnormalities (14/15), hypotonia (15/18), and skeletal anomalies (5/17). One patient exhibited mildly elevated alkaline phosphatase levels. All harbored biallelic PIGC variants, with 14 out of 18 of those being homozygous variants. Analysis of samples derived from probands and cellular models showed reduced cell surface levels of GPI-APs. This study confirms the association of PIGC biallelic variants with refractory seizures, severe developmental and cognitive impairments, and highlights their association with childhood-onset mortality. Additionally, it shows that dysfunctional PIGC results in defective biosynthesis of GPI-AP.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All clinical data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Fujita M, Kinoshita T. GPI-anchor remodeling: potential functions of GPI-anchors in intracellular trafficking and membrane dynamics. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1821:1050–8.

Kinoshita T, Fujita M. Biosynthesis of GPI-anchored proteins: special emphasis on GPI lipid remodeling. J Lipid Res. 2016;57:6–24.

Fujita M, Kinoshita T. Structural remodeling of GPI anchors during biosynthesis and after attachment to proteins. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:1670–7.

Wu T, Yin F, Guang S, He F, Yang L, Peng J. The Glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis pathway in human diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15:129.

Bellai-Dussault K, Nguyen TTM, Baratang NV, Jimenez-Cruz DA, Campeau PM. Clinical variability in inherited glycosylphosphatidylinositol deficiency disorders. Clin Genet. 2019;95:112–21.

Kinoshita T. Biosynthesis and biology of mammalian GPI-anchored proteins. Open Biol. 2020;10:190290.

Shamseldin HE, Tulbah M, Kurdi W, Nemer M, Alsahan N, Al Mardawi E, et al. Identification of embryonic lethal genes in humans by autozygosity mapping and exome sequencing in consanguineous families. Genome Biol. 2015;16:116.

Edvardson S, Murakami Y, Nguyen TT, Shahrour M, St-Denis A, Shaag A, et al. Mutations in the phosphatidylinositol glycan C (PIGC) gene are associated with epilepsy and intellectual disability. J Med Genet. 2017;54:196–201.

Pons L, Sabatier I, Alix E, Faoucher M, Labalme A, Sanlaville D, et al. Multisystem disorders, severe developmental delay and seizures in two affected siblings, expanding the phenotype of PIGC deficiency. Eur J Med Genet. 2020;63:103994.

Investigators GPP, Smedley D, Smith KR, Martin A, Thomas EA, McDonagh EM, et al. 100,000 Genomes Pilot on Rare-Disease Diagnosis in Health Care - Preliminary Report. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:1868–80.

Faundes V, Newman WG, Bernardini L, Canham N, Clayton-Smith J, Dallapiccola B, et al. Histone lysine methylases and demethylases in the landscape of human developmental disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102:175–87.

Jackson A, Banka S, Stewart H, Genomics England Research C, Robinson H, Lovell S, et al. Recurrent KCNT2 missense variants affecting p.Arg190 result in a recognizable phenotype. Am J Med Genet A. 2021;185:3083–91.

Pagnamenta AT, Jackson A, Perveen R, Beaman G, Petts G, Gupta A, et al. Biallelic TMEM260 variants cause truncus arteriosus, with or without renal defects. Clin Genet. 2022;101:127–33.

Jackson A, Moss C, Chandler KE, Balboa PL, Bageta ML, Petrof G, et al. Biallelic TUFT1 variants cause woolly hair, superficial skin fragility and desmosomal defects. Br J Dermatol. 2023;188:75–83.

Ionita-Laza I, McCallum K, Xu B, Buxbaum JD. A spectral approach integrating functional genomic annotations for coding and noncoding variants. Nat Genet. 2016;48:214–20.

Shihab HA, Rogers MF, Gough J, Mort M, Cooper DN, Day IN, et al. An integrative approach to predicting the functional effects of non-coding and coding sequence variation. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:1536–43.

Chun S, Fay JC. Identification of deleterious mutations within three human genomes. Genome Res. 2009;19:1553–61.

Jagadeesh KA, Wenger AM, Berger MJ, Guturu H, Stenson PD, Cooper DN, et al. M-CAP eliminates a majority of variants of uncertain significance in clinical exomes at high sensitivity. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1581–6.

Schwarz JM, Rodelsperger C, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster evaluates disease-causing potential of sequence alterations. Nat Methods. 2010;7:575–6.

Choi Y, Sims GE, Murphy S, Miller JR, Chan AP. Predicting the functional effect of amino acid substitutions and indels. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46688.

Kumar P, Henikoff S, Ng PC. Predicting the effects of coding non-synonymous variants on protein function using the SIFT algorithm. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:1073–81.

Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405–24.

Inoue N, Watanabe R, Takeda J, Kinoshita T. PIG-C, one of the three human genes involved in the first step of glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis is a homologue of Saccharomyces cerevisiae GPI2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;226:193–9.

Hug N, Longman D, Caceres JF. Mechanism and regulation of the nonsense-mediated decay pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:1483–95.

Inoue WatanabeR, Westfall N, Taron B, Orlean CH, Takeda P, Kinoshita J. T. The first step of glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis is mediated by a complex of PIG-A, PIG-H, PIG-C and GPI1. EMBO J. 1998;17:877–85.

Miyata T, Takeda J, Iida Y, Yamada N, Inoue N, Takahashi M, et al. The cloning of PIG-A, a component in the early step of GPI-anchor biosynthesis. Science. 1993;259:1318–20.

Kamitani T, Chang HM, Rollins C, Waneck GL, Yeh ET. Correction of the class H defect in glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchor biosynthesis in Ltk- cells by a human cDNA clone. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20733–6.

Watanabe R, Murakami Y, Marmor MD, Inoue N, Maeda Y, Hino J, et al. Initial enzyme for glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis requires PIG-P and is regulated by DPM2. EMBO J. 2000;19:4402–11.

Murakami Y, Siripanyaphinyo U, Hong Y, Tashima Y, Maeda Y, Kinoshita T. The initial enzyme for glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis requires PIG-Y, a seventh component. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5236–46.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the families for cooperating in this study. This research was made possible through access to data in the National Genomic Research Library, which is managed by Genomics England Limited (a wholly owned company of the Department of Health and Social Care). The National Genomic Research Library holds data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and data collected as part of their participation in research. The National Genomic Research Library is funded by the National Institute for Health Research and NHS England. The Wellcome Trust, Cancer Research UK and the Medical Research Council have also funded research infrastructure.

Funding

AB is funded by a BRIDGE - Translational Excellence Programme grant funded by the Novo Nordisk Foundation, grant agreement number: NNF20SA0064340. PMC is supported by awards from the CIHR and the FRQS. MZ is supported by Science and Technology Development Fund (STDF) grant 33650. MIUR project “Dipartimenti di Eccellenza 2023-2027” to the Department of Neurosciences “Rita Levi Montalcini” (University of Turin); Italian Ministry for Education, University and Research (Ministero dell’Istruzione, dell’Università e della Ricerca - MIUR) PRIN2020 code 20203P8C3X. The whole-exome sequencing was performed as part of the Autism Sequencing Consortium and was supported by the NIMH (MH111661). This research was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Oxford Biomedical Research Centre (BRC) Programme and the Wellcome Trust (203141/Z/16/Z). This study has been delivered through the NIHR Manchester BRC (NIHR203308). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the, the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Dr Adam Jackson is supported by Solve-RD. The Solve-RD project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 779257.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: A.B., P.M.C.; Writing-review & editing: A.B., M.C.B., P.M.C.; Methodology: S.S., H.B., T.T.M.N.; Investigation – functional experiments: S.S., H.B., T.T.M.N., T.K., Y.M., D.L., P.M.C.; Writing-original draft: S.S.; Reviewed the final draft: A.B., M.C.B., S.S., H.B., M.S.Z., T.T.M.N., A.A.S., D.C., A.B., G.B.F., E.H., I.K., T.B., A.K., J.G.G., H.H., N.D., A.J., S.D., G.E.R.C., S.B., T.K., R.M., Y.M., P.M.C.; Investigation - proband recruitment, clinical and diagnostic evaluation: M.C.B., M.S.Z., A.A.S., D.C., A.B., G.B.F., E.H., I.K., T.B., A.K., J.G.G., H.H., N.D., A.J., S.D.H., S.B., A.J.M, A.S., H.M.E., M.T., M.H., M.N., P.N., R.A.J., R.A., P.M.C.; Funding acquisition: P.M.C., A.B.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

We declare that the authors do not have any conflict of interest, and all have read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics declaration

The study protocol was approved by CHU Sainte-Justine Research Ethics Board (#MP-21-2016-962). Samples were collected from probands and families after written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians, and the data was de-identified. A written medical photography consent was obtained from the parents of P6, P9, P10, P11, and P12.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bayat, A., Borroto, M.C., Salian, S. et al. PIGC-related encephalopathy: Lessons learned from 18 new probands. Eur J Hum Genet 33, 1636–1646 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-025-01923-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41431-025-01923-9