Abstract

Purpose

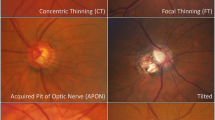

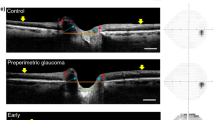

To investigate the association between the laminar dot sign (LDS) and the deep optic nerve head (ONH) structure in eyes with primary-open-angle glaucoma (POAG).

Methods

Eighty-four eyes of 84 patients with POAG were prospectively included. All of the patients underwent stereo optic disc photography (SDP), red-free retinal nerve fibre layer (RNFL) photography, SS-OCT, and standard automated perimetry. By evaluating the SDP, patients were classified into laminar dot sign (LDS) and non-LDS groups. The deep structure of the ONH including the anterior prelaminar depth (APLD) and prelaminar tissue thickness (PTT) were quantitated using SS-OCT. Progression was assessed by structural or functional deterioration during the average 4.3 ± 1.2 years of follow-up.

Results

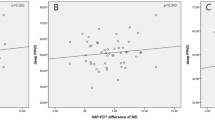

The LDS group had deeper APLD (405.47 ± 107.55 vs. 302.45 ± 149.51, P < 0.001) and thinner PTT (74.34 ± 24.46 vs. 137.29 ± 40.07, P = 0.001) relative to the non-LDS group. By multivariate analysis, thin PTT was significantly associated with the presence of LDS (odds ratio = 0.939, P < 0.001). Structural progression was detected in 45 eyes (84.9%) in the LDS group and 8 eyes (25.8%) in the non-LDS group. Functional progression was demonstrated in 29 eyes (34.5%) in the LDS group and 6 eyes (19.4%) in the non-LDS group. The eyes with LDS had a significantly higher risk of glaucoma progression (χ2 = 5.00, degree of freedom = 1, P = 0.033).

Conclusions

In eyes with POAG, the presence of LDS was associated with thinner prelaminar tissue and faster disease progression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

References

Hernandez MR, Igoe F, Neufeld AH. Extracellular matrix of the human optic nerve head. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;102:139–48.

Anderson DR, Hoyt WF. Ultrastructure of intraorbital portion of human and monkey optic nerve. Arch Ophthalmol. 1969;82:506–30.

Lee EJ, Kim TW, Kim M, Kim H. Influence of lamina cribrosa thickness and depth on the rate of progressive retinal nerve fiber layer thinning. Ophthalmology. 2015;122:721–9.

Kim DW, Jeoung JW, Kim YW, Girard MJ, Mari JM, Kim YK, et al. Prelamina and lamina cribrosa in glaucoma patients with unilateral visual field loss. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57:1662–70.

Parrish RK 2nd, Feuer WJ, Schiffman JC, Lichter PR, Musch DC. Five-year follow-up optic disc findings of the Collaborative Initial Glaucoma Treatment Study. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009;147:717–24. e1

Reis AS, O’Leary N, Stanfield MJ, Shuba LM, Nicolela MT, Chauhan BC. Laminar displacement and prelaminar tissue thickness change after glaucoma surgery imaged with optical coherence tomography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:5819–26.

Barrancos C, Rebolleda G, Oblanca N, Cabarga C, Munoz-Negrete FJ. Changes in lamina cribrosa and prelaminar tissue after deep sclerectomy. Eye. 2014;28:58–65.

Agoumi Y, Sharpe GP, Hutchison DM, Nicolela MT, Artes PH, Chauhan BC. Laminar and prelaminar tissue displacement during intraocular pressure elevation in glaucoma patients and healthy controls. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:52–9.

Trivli A, Koliarakis I, Terzidou C, Goulielmos GN, Siganos CS, Spandidos DA, et al. Normal-tension glaucoma: pathogenesis and genetics. Exp Ther Med. 2019;17:563–74.

Mozaffarieh M, Flammer J. New insights in the pathogenesis and treatment of normal tension glaucoma. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2013;13:43–49.

Huang D, Swanson EA, Lin CP, Schuman JS, Stinson WG, Chang W, et al. Optical coherence tomography. Science. 1991;254:1178–81.

Schuman JS, Pedut-Kloizman T, Pakter H, Wang N, Guedes V, Huang L, et al. Optical coherence tomography and histologic measurements of nerve fiber layer thickness in normal and glaucomatous monkey eyes. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48:3645–54.

Spaide RF, Koizumi H, Pozzoni MC. Enhanced depth imaging spectral-domain optical coherence tomography. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:496–500.

Srinivasan VJ, Adler DC, Chen Y, Gorczynska I, Huber R, Duker JS, et al. Ultrahigh-speed optical coherence tomography for three-dimensional and en face imaging of the retina and optic nerve head. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:5103–10.

Deleon-Ortega JE, Arthur SN, McGwin G Jr., Xie A, Monheit BE, Girkin CA. Discrimination between glaucomatous and nonglaucomatous eyes using quantitative imaging devices and subjective optic nerve head assessment. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:3374–80.

Vessani RM, Moritz R, Batis L, Zagui RB, Bernardoni S, Susanna R. Comparison of quantitative imaging devices and subjective optic nerve head assessment by general ophthalmologists to differentiate normal from glaucomatous eyes. J Glaucoma. 2009;18:253–61.

Read RM, Spaeth GL. The practical clinical appraisal of the optic disc in glaucoma: the natural history of cup progression and some specific disc-field correlations. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1974;78:Op255–74.

Healey PR, Mitchell P. Visibility of lamina cribrosa pores and open-angle glaucoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138:871–2.

Kim YW, Jeoung JW, Kim DW, Girard MJ, Mari JM, Park KH, et al. Clinical assessment of lamina cribrosa curvature in eyes with primary open-angle glaucoma. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0150260.

Girard MJ, Tun TA, Husain R, Acharyya S, Haaland BA, Wei X, et al. Lamina cribrosa visibility using optical coherence tomography: comparison of devices and effects of image enhancement techniques. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:865–74.

Mari JM, Strouthidis NG, Park SC, Girard MJ. Enhancement of lamina cribrosa visibility in optical coherence tomography images using adaptive compensation. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:2238–47.

Heijl A, Leske MC, Bengtsson B, Bengtsson B, Hussein M. Measuring visual field progression in the Early Manifest Glaucoma Trial. Acta Ophthalmol Scand. 2003;81:286–93.

Lee EJ, Kim TW, Weinreb RN. Reversal of lamina cribrosa displacement and thickness after trabeculectomy in glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1359–66.

Jung YH, Park HY, Jung KI, Park CK. Comparison of prelaminar thickness between primary open angle glaucoma and normal tension glaucoma patients. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0120634.

Burgoyne CF, Downs JC, Bellezza AJ, Suh JK, Hart RT. The optic nerve head as a biomechanical structure: a new paradigm for understanding the role of IOP-related stress and strain in the pathophysiology of glaucomatous optic nerve head damage. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2005;24:39–73.

Bellezza AJ, Rintalan CJ, Thompson HW, Downs JC, Hart RT, Burgoyne CF. Deformation of the lamina cribrosa and anterior scleral canal wall in early experimental glaucoma. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44:623–37.

Park SC, Brumm J, Furlanetto RL, Netto C, Liu Y, Tello C, et al. Lamina cribrosa depth in different stages of glaucoma. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:2059–64.

Malik R, Swanson WH, Garway-Heath DF. ‘Structure-function relationship’ in glaucoma: past thinking and current concepts. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2012;40:369–80.

Kass MA, Heuer DK, Higginbotham EJ, Johnson CA, Keltner JL, Miller JP, et al. The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study: a randomized trial determines that topical ocular hypotensive medication delays or prevents the onset of primary open-angle glaucoma. Arch Ophthalmol. 2002;120:701–13. discussion 829-30

Medeiros FA, Alencar LM, Zangwill LM, Bowd C, Sample PA, Weinreb RN. Prediction of functional loss in glaucoma from progressive optic disc damage. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127:1250–6.

Chauhan BC, Nicolela MT, Artes PH. Incidence and rates of visual field progression after longitudinally measured optic disc change in glaucoma. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2110–8.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bak, E., Lee, W.J., Kim, JS. et al. Deep optic nerve head morphology and glaucoma progression in eyes with and without laminar dot sign: a longitudinal comparative study. Eye 35, 936–944 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-1001-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-020-1001-2