Abstract

Objectives

To assess the association between far vision impairment (objective and subjective) and perceived stress among older adults from six low- and middle-income countries (LMICs, i.e., China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, and South Africa).

Methods

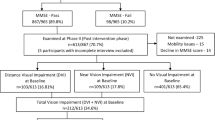

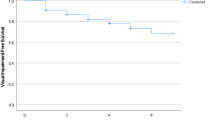

Data from the WHO Study on global AGEing and adult health were analyzed. Objective visual acuity was measured using the tumbling E LogMAR chart and was used as a four-category variable (no, mild, moderate, and severe visual impairment). Subjective visual impairment referred to difficulty in seeing and recognizing an object or a person across the road. Using two questions from the Perceived Stress Scale, a perceived stress variable was computed, and ranged from 0 (lowest stress) to 100 (highest stress). Multivariable linear regression with perceived stress as the outcome was conducted.

Results

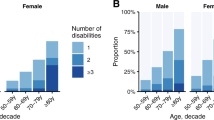

Data on 14,585 adults aged ≥65 years [mean (SD) age 72.6 (11.5) years; 55.0% females] were analyzed. Only severe objective visual impairment (versus no visual impairment) was significantly associated with higher levels of stress (b = 6.91; 95% CI = 0.94–12.89). In terms of subjective visual impairment, compared with no visual impairment, mild (b = 2.67; 95% CI = 0.56–4.78), moderate (b = 8.18; 95% CI = 5.84–10.52), and severe (b = 11.86; 95% CI = 9.11–14.61) visual impairment were associated with significantly higher levels of perceived stress.

Conclusions

This large study showed that far vision impairment was associated with increased perceived stress levels among older adults in LMICs. Increased availability of eye care services may reduce stress among those with visual impairment in LMICs, while more research is needed to better characterize the directionality of the far vision impairment–perceived stress relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Log in or create a free account to read this content

Gain free access to this article, as well as selected content from this journal and more on nature.com

or

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available in the Global Ageing and Adult Health Survey repository, available at http://www.who.int/healthinfo/sage/en.

References

World Health Organization. Ageing and health. 2018. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health. Accessed 9 Apr 2021.

GBD 2019 Blindness and Vision Impairment Collaborators, Vision Loss Expert Group of the Global Burden of Disease Study. Trends in prevalence of blindness and distance and near vision impairment over 30 years: an analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet Glob Health. 2021;9:e130–43.

Franzen SRP, Chandler C, Lang T. Health research capacity development in low and middle income countries: reality or rhetoric? A systematic meta-narrative review of the qualitative literature. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e012332.

World Health Organization. Blindness and vision impairment. 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment. Accessed 26 Nov 2020.

Sabel BA, Wang J, Cárdenas-Morales L, Faiq M, Heim C. Mental stress as consequence and cause of vision loss: the dawn of psychosomatic ophthalmology for preventive and personalized medicine. EPMA J 2018;9:133–60.

Gellman MD, Turner JR. Encyclopedia of behavioral medicine. New York: Springer-Verlag New York; 2013. p. 2116. https://www.springer.com/fr/book/9781441910059#otherversion=9781441910042.

Grignolo FM, Bongioanni C, Carenini BB. [Variations of intraocular pressure induced by psychological stress (author’s transl)]. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 1977;170:562–9.

Gelber GS, Schatz H. Loss of vision due to central serous chorioretinopathy following psychological stress. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:46–50.

Marc A, Stan C. [Effect of physical and psychological stress on the course of primary open angle glaucoma]. Oftalmologia 2013;57:60–6.

Williams RA, Brody BL, Thomas RG, Kaplan RM, Brown SI. The psychosocial impact of macular degeneration. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116:514–20.

Pinquart M, Pfeiffer JP. Psychological well-being in visually impaired and unimpaired individuals: a meta-analysis. Br J Vis Impairment. 2011;29:27–45.

Lehane CM, Dammeyer J, Wittich W. Intra- and interpersonal effects of coping on the psychological well-being of adults with sensory loss and their spouses. Disabil Rehabilitation. 2019;41:796–807.

Khairallah M, Kahloun R, Bourne R, Limburg H, Flaxman SR, Jonas JB, et al. Number of people blind or visually impaired by cataract worldwide and in world regions, 1990 to 2010. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:6762–9.

Jonas JB, Cheung CMG, Panda-Jonas S. Updates on the epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration. Asia Pac J Ophthalmol (Philos). 2017;6:493–7.

Cong R, Zhou B, Sun Q, Gu H, Tang N, Wang B. Smoking and the risk of age-related macular degeneration: a meta-analysis. Ann Epidemiol. 2008;18:647–56.

Laugero KD, Falcon LM, Tucker KL. Relationship between perceived stress and dietary and activity patterns in older adults participating in the Boston Puerto Rican Health Study. Appetite 2011;56:194–204.

Islam FMA, Chong EW, Hodge AM, Guymer RH, Aung KZ, Makeyeva GA, et al. Dietary patterns and their associations with age-related macular degeneration: The Melbourne Collaborative Cohort Study. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1428.e2.

Stubbs B, Veronese N, Vancampfort D, Prina AM, Lin P-Y, Tseng P-T, et al. Perceived stress and smoking across 41 countries: a global perspective across Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7597.

Jiang H, Wang L-N, Liu Y, Li M, Wu M, Yin Y, et al. Physical activity and risk of age-related cataract. Int J Ophthalmol. 2020;13:643–9.

Sabel BA, Wang J, Fähse S, Cárdenas-Morales L, Antal A. Personality and stress influence vision restoration and recovery in glaucoma and optic neuropathy following alternating current stimulation: implications for personalized neuromodulation and rehabilitation. EPMA J 2020;11:177–96.

Dada T, Mittal D, Mohanty K, Faiq MA, Bhat MA, Yadav RK, et al. Mindfulness meditation reduces intraocular pressure, lowers stress biomarkers and modulates gene expression in glaucoma: a randomized controlled trial. J Glaucoma. 2018;27:1061–7.

Zhang X, Bullard KM, Cotch MF, Wilson MR, Rovner BW, McGwin G, et al. Association between depression and functional vision loss in persons 20 years of age or older in the United States, NHANES 2005–2008. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:573–81.

Kowal P, Chatterji S, Naidoo N, Biritwum R, Fan W, Ridaura RL, et al. Data resource profile: the World Health Organization Study on Global Ageing and Adult Health (SAGE). Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1639–49.

DeVylder JE, Koyanagi A, Unick J, Oh H, Nam B, Stickley A. Stress sensitivity and psychotic experiences in 39 low- and middle-income countries. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42:1353–62.

Stubbs B, Koyanagi A, Thompson T, Veronese N, Carvalho AF, Solomi M, et al. The epidemiology of back pain and its relationship with depression, psychosis, anxiety, sleep disturbances, and stress sensitivity: data from 43 low- and middle-income countries. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;43:63–70.

Vancampfort D, Koyanagi A, Ward PB, Veronese N, Carvalho AF, Solmi M, et al. Perceived stress and its relationship with chronic medical conditions and multimorbidity among 229,293 community-dwelling adults in 44 low- and middle-income countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:979–89.

Koyanagi A, Oh H, Vancampfort D, Carvalho AF, Veronese N, Stubbs B, et al. Perceived stress and mild cognitive impairment among 32,715 community-dwelling older adults across six low- and middle-income countries. Gerontology 2019;65:155–63.

Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24:385–96.

Smith L, Shin JI, Jacob L, López-Sánchez GF, Oh H, Barnett Y, et al. The association between objective vision impairment and mild cognitive impairment among older adults in low- and middle-income countries. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021.

Ehrlich JR, Stagg BC, Andrews C, Kumagai A, Musch DC. Vision impairment and receipt of eye care among older adults in low- and middle-income countries. JAMA Ophthalmol 2019;137:146–58.

Rose GA. The diagnosis of ischaemic heart pain and intermittent claudication in field surveys. Bull World Health Organ. 1962;27:645–58.

Koyanagi A, Garin N, Olaya B, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S, Leonardi M, et al. Chronic conditions and sleep problems among adults aged 50 years or over in nine countries: a multi-country study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e114742.

Koyanagi A, Lara E, Stubbs B, Carvalho AF, Oh H, Stickley A, et al. Chronic physical conditions, multimorbidity, and mild cognitive impairment in low- and middle-income countries. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2018;66:721–7.

Verstraten PFJ, Brinkmann WLJH, Stevens NL, Schouten JSAG. Loneliness, adaptation to vision impairment, social support and depression among visually impaired elderly. Int Congr Ser. 2005;1282:317–21.

Huang L-J, Du W-T, Liu Y-C, Guo L-N, Zhang J-J, Qin M-M, et al. Loneliness, stress, and depressive symptoms among the Chinese rural empty nest elderly: a moderated mediation analysis. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2019;40:73–8.

Guan X, Fu M, Lin F, Zhu D, Vuillermin D, Shi L. Burden of visual impairment associated with eye diseases: exploratory survey of 298 Chinese patients. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e030561.

Kolawole OU, Ashaye AO, Mahmoud AO, Adeoti CO. Cataract blindness in Osun State, Nigeria: results of a survey. Middle East Afr J Ophthalmol. 2012;19:364–71.

Martínez de Toda I, Miguélez L, Siboni L, Vida C, De la Fuente M. High perceived stress in women is linked to oxidation, inflammation and immunosenescence. Biogerontology 2019;20:823–35.

Klein R, Myers CE, Cruickshanks KJ, Gangnon RE, Danforth LG, Sivakumaran TA, et al. Markers of inflammation, oxidative stress, and endothelial dysfunction and the 20-year cumulative incidence of early age-related macular degeneration: The Beaver Dam Eye Study. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2014;132:446–55.

Forsman E, Kivelä T, Vesti E. Lifetime visual disability in open-angle glaucoma and ocular hypertension. J Glaucoma. 2007;16:313–9.

Novak M, Björck L, Giang KW, Heden-Ståhl C, Wilhelmsen L, Rosengren A. Perceived stress and incidence of Type 2 diabetes: a 35-year follow-up study of middle-aged Swedish men. Diabet Med. 2013;30:e8–16.

Faulenbach M, Uthoff H, Schwegler K, Spinas GA, Schmid C, Wiesli P. Effect of psychological stress on glucose control in patients with Type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012;29:128–31.

Onakpoya OH, Kolawole BA, Adeoye AO, Adegbehingbe BO, Laoye O. Visual impairment and blindness in type 2 diabetics: Ife-Ijesa diabetic retinopathy study. Int Ophthalmol. 2016;36:477–85.

Ren C, Liu W, Li J, Cao Y, Xu J, Lu P. Physical activity and risk of diabetic retinopathy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Diabetol. 2019;56:823–37.

Bonovas S, Filioussi K, Tsantes A, Peponis V. Epidemiological association between cigarette smoking and primary open-angle glaucoma: a meta-analysis. Public Health. 2004;118:256–61.

Lee MJ, Wang J, Friedman DS, Boland MV, De Moraes CG, Ramulu PY. Greater physical activity is associated with slower visual field loss in glaucoma. Ophthalmology 2019;126:958–64.

El-Gasim M, Munoz B, West SK, Scott AW. Discrepancies in the concordance of self-reported vision status and visual acuity in the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. Ophthalmology 2012;119:106–11.

Yip JLY, Khawaja AP, Broadway D, Luben R, Hayat S, Dalzell N, et al. Visual acuity, self-reported vision and falls in the EPIC-Norfolk Eye study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:377–82.

Ramke J, Petkovic J, Welch V, Blignault I, Gilbert C, Blanchet K, et al. Interventions to improve access to cataract surgical services and their impact on equity in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;11:CD011307.

Kaluza G, Strempel I. Training in relaxation and visual imagery with patients who have open-angle glaucoma. Int J Rehab Health. 1995;1:261–73.

Amore FM, Paliotta S, Silvestri V, Piscopo P, Turco S, Reibaldi A. Biofeedback stimulation in patients with age-related macular degeneration: comparison between 2 different methods. Can J Ophthalmol. 2013;48:431–7.

Prior A, Fenger-Grøn M, Larsen KK, Larsen FB, Robinson KM, Nielsen MG, et al. The association between perceived stress and mortality among people with multimorbidity: a prospective population-based cohort study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016;184:199–210.

Acknowledgements

This paper uses data from WHO’s Study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). SAGE is supported by the US National Institute on Aging through Interagency Agreements OGHA 04034785, YA1323–08-CN-0020, Y1-AG-1005–01, and through research grants R01-AG034479 and R21-AG034263.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LJ contributed to the design of the study, managed the literature searches, wrote the first draft of the manuscript, and corrected the manuscript. KK, LS, GFL-S, SP, HO, JIS, ASA, and JMH contributed to the design of the study and corrected the manuscript. AK contributed to the design of the study, performed the statistical analyses, and corrected the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jacob, L., Kostev, K., Smith, L. et al. Association of objective and subjective far vision impairment with perceived stress among older adults in six low- and middle-income countries. Eye 36, 1274–1280 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01634-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-021-01634-7