Abstract

Background/Objectives

Dry eye disease (DED) is an exceedingly common diagnosis in patients, yet recent analyses have demonstrated patient education materials (PEMs) on DED to be of low quality and readability. Our study evaluated the utility and performance of three large language models (LLMs) in enhancing and generating new patient education materials (PEMs) on dry eye disease (DED).

Subjects/Methods

We evaluated PEMs generated by ChatGPT-3.5, ChatGPT-4, Gemini Advanced, using three separate prompts. Prompts A and B requested they generate PEMs on DED, with Prompt B specifying a 6th-grade reading level, using the SMOG (Simple Measure of Gobbledygook) readability formula. Prompt C asked for a rewrite of existing PEMs at a 6th-grade reading level. Each PEM was assessed on readability (SMOG, FKGL: Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level), quality (PEMAT: Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool, DISCERN), and accuracy (Likert Misinformation scale).

Results

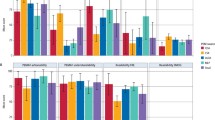

All LLM-generated PEMs in response to Prompt A and B were of high quality (median DISCERN = 4), understandable (PEMAT understandability ≥70%) and accurate (Likert Score=1). LLM-generated PEMs were not actionable (PEMAT Actionability <70%).

ChatGPT-4 and Gemini Advanced rewrote existing PEMs (Prompt C) from a baseline readability level (FKGL: 8.0 ± 2.4, SMOG: 7.9 ± 1.7) to targeted 6th-grade reading level; rewrites contained little to no misinformation (median Likert misinformation=1 (range: 1–2)). However, only ChatGPT-4 rewrote PEMs while maintaining high quality and reliability (median DISCERN = 4).

Conclusion

LLMs (notably ChatGPT-4) were able to generate and rewrite PEMs on DED that were readable, accurate, and high quality. Our study underscores the value of leveraging LLMs as supplementary tools to improving PEMs.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 18 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $14.39 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are available within the manuscript and within its supporting supplementary information.

References

Craig JP, Nichols KK, Akpek EK, Caffery B, Dua HS, Joo CK, et al. TFOS DEWS II definition and classification report. Ocul Surf. 2017;15:276–83.

Farrand KF, Fridman M, Stillman IÖ, Schaumberg DA. Prevalence of diagnosed dry eye disease in the United States among adults aged 18 years and older. Am J Ophthalmol. 2017;182:90–8.

Elhusseiny AM, Khalil AA, El Sheikh RH, Bakr MA, Eissa MG, El Sayed YM. New approaches for diagnosis of dry eye disease. Int J Ophthalmol. 2019;12:1618–28.

Zhang X, Zhao L, Deng S, Sun X, Wang N. Dry eye syndrome in patients with diabetes mellitus: prevalence, etiology, and clinical characteristics. J Ophthalmol. 2016;2016:8201053.

de Paiva CS. Effects of aging in dry eye. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 2017;57:47–64.

Wróbel-Dudzińska D, Osial N, Stępień PW, Gorecka A, Żarnowski T. Prevalence of dry eye symptoms and associated risk factors among university students in Poland. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:1313.

Elhusseiny AM, Eleiwa TK, Yacoub MS, George J, ElSheikh RH, Haseeb A, et al. Relationship between screen time and dry eye symptoms in pediatric population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ocul Surf. 2021;22:117–9.

Xu L, Zhang W, Zhu XY, Suo T, Fan XQ, Fu Y. Smoking and the risk of dry eye: a meta-analysis. Int J Ophthalmol. 2016;9:1480–6.

Uchino M, Schaumberg DA. Dry eye disease: impact on quality of life and vision. Curr Ophthalmol Rep. 2013;1:51–7.

Miljanović B, Dana R, Sullivan DA, Schaumberg DA. Impact of dry eye syndrome on vision-related quality of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143:409–15.

Inomata T, Iwagami M, Nakamura M, Shiang T, Yoshimura Y, Fujimoto K, et al. Characteristics and risk factors associated with diagnosed and undiagnosed symptomatic dry eye using a smartphone application. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138:58–68.

Wang MTM, Diprose WK, Craig JP. Epidemiologic research in dry eye disease and the utility of mobile health technology. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2020;138:69–70.

Weiss BD Health literacy: help your patients understand: a continuing medical education (CME) program that provides tools to enhance patient care, improve office productivity, and reduce healthcare costs. Chicago, Ill.: American Medical Association Foundation and American Medical Association; 2003.

Brega AG, Barnard J, Mabachi NM, Weiss BD, DeWalt DA, Brach C, et al. AHRQ Health Literacy Universal Precautions Toolkit [Internet]. 2nd Edition. Rockville, MD: Agnecy for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2020 [cited 2024 Mar 7]. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/improve/precautions/toolkit.html.

Huang G, Fang CH, Agarwal N, Bhagat N, Eloy JA, Langer PD. Assessment of online patient education materials from major ophthalmologic associations. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133:449–54.

Agarwal N, Hansberry DR, Sabourin V, Tomei KL, Prestigiacomo CJ. A comparative analysis of the quality of patient education materials from medical specialties. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1257.

Hansberry DR, Agarwal N, Shah R, Schmitt PJ, Baredes S, Setzen M, et al. Analysis of the readability of patient education materials from surgical subspecialties. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:405–12.

Oydanich M, Kuklinski E, Asbell PA. Assessing the quality, reliability, and readability of online information on dry eye disease. Cornea. 2022;41:1023–8.

Edmunds MR, Barry RJ, Denniston AK. Readability assessment of online ophthalmic patient information. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2013;131:1610–6.

Arvisais-Anhalt S, Gonias SL, Murray SG. Establishing priorities for implementation of large language models in pathology and laboratory medicine. Acad Pathol. 2024;11:100101.

Kianian R, Sun D, Crowell EL, Tsui E. The use of large language models to generate education materials about uveitis. Oph Retin. 2024;8:195–201.

OpenAI. Introducing ChatGPT [Internet]. 2022 [cited 2024 Mar 7]. Available from: https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt.

Open AI, Achiam J, Adler S, Agarwal S, Ahmad L, Akkaya I, et al. GPT-4 Technical Report [Internet]. arXiv. 2024. http://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774 [cited 2024 Mar 7]. Available from.

Gemini Team, Anil R, Borgeaud S, Wu Y, Alayrac JB, Yu J, et al. Gemini: a family of highly capable multimodal models [Internet]. arXiv; 2023 [cited 2024 Mar 7]. Available from: http://arxiv.org/abs/2312.11805.

Insights C The Value of Google Result Positioning [Internet]. Westborough: Chitika Inc; 2013 Jun [cited 2024 Mar 7] p. 0–10. Available from: https://research.chitika.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/chitikainsights-valueofgoogleresultspositioning.pdf.

Kincaid JP, Fishburne JR, Robert PR, Richard LC, Brad S Derivation of New Readability Formulas (Automated Readability Index, Fog Count and Flesch Reading Ease Formula) for Navy Enlisted Personnel: [Internet]. Fort Belvoir, VA: Defense Technical Information Center; 1975 Feb [cited 2024 Mar 7]. Available from: http://www.dtic.mil/docs/citations/ADA006655.

Mc Laughlin GH. SMOG grading-a new readability formula. J Read. 1969;12:639–46.

Martin CA, Khan S, Lee R, Do AT, Sridhar J, Crowell EL, et al. Readability and suitability of online patient education materials for glaucoma. Ophthalmol Glaucoma. 2022;5:525–30.

Kirchner A, Kulkarni V, Rajkumar J, Usman A, Hassan S, Lee EY. Readability assessment of patient-facing online educational content for pyoderma gangrenosum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:1127–8.

Crabtree L, Lee E. Assessment of the readability and quality of online patient education materials for the medical treatment of open-angle glaucoma. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2022;7:e000966.

Readability Formulas [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 7]. Readability Scoring System. Available from: https://readabilityformulas.com/readability-scoring-system.php#formulaResults.

Charnock D, Shepperd S, Needham G, Gann R. DISCERN: an instrument for judging the quality of written consumer health information on treatment choices. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:105–11.

AHRQ. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2020 [cited 2024 Mar 7]. The Patient Education Materials Assessment Tool (PEMAT) and User’s Guide: Introduction. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/health-literacy/patient-education/pemat1.html.

Veeramani A, Johnson AR, Lee BT, Dowlatshahi AS Readability, Understandability, Usability, and Cultural Sensitivity of Online Patient Educational Materials (PEMs) for Lower Extremity Reconstruction: A Cross-Sectional Study. Plast Surg (Oakv). 2022 Sep;22925503221120548.

Shoemaker SJ, Wolf MS, Brach C. Development of the patient education materials assessment tool (PEMAT): a new measure of understandability and actionability for print and audiovisual patient information. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;96:395–403.

Pan A, Musheyev D, Bockelman D, Loeb S, Kabarriti AE. Assessment of artificial intelligence chatbot responses to top searched queries about cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2023;9:1437–40.

Loeb S, Sengupta S, Butaney M, Macaluso JN, Czarniecki SW, Robbins R, et al. Dissemination of misinformative and biased information about prostate cancer on YouTube. Eur Urol. 2019;75:564–7.

Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T, Wedding D, Gwet KL. A comparison of Cohen’s Kappa and Gwet’s AC1 when calculating inter-rater reliability coefficients: a study conducted with personality disorder samples. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:61.

Wu Z, Schmitz-Valckenberg S, Blodi BA, Holz FG, Jaffe GJ, Liakopoulos S, et al. Reticular Pseudodrusen: Interreader Agreement of Evaluation on OCT Imaging in Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmology Science [Internet]. 2023 Dec [cited 2024 Mar 7];3. Available from: https://www.ophthalmologyscience.org/article/S2666-9145(23)00057-X/fulltext.

OpenAI. OpenAI Platform. Prompt Engineering. Available from: https://platform.openai.com.

Reed JM. Using generative AI to produce images for nursing education. Nurse Educator. 2023;48:246.

Wang C, Liu S, Yang H, Guo J, Wu Y, Liu J. Ethical considerations of using ChatGPT in health care. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e48009.

OpenAI. Terms of use. 2024 [cited 2024 Aug 22]. Terms of use. Available from: https://openai.com/policies/row-terms-of-use/.

Jacobs W, Amuta AO, Jeon KC Health information seeking in the digital age: An analysis of health information seeking behavior among US adults. Cogent Social Sciences [Internet]. 2017 Jan [cited 2024 Aug 23]; Available from: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/23311886.2017.1302785.

Lewandowski D In: Understanding search engines. Cham: Springer; 2023. p. 1–10.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

QAD was responsible for data analysis, and contribution to drafting of the original draft of the manuscript. ADB and AME were responsible for patient education material review, and critical review of the final manuscript. MZC was responsible for data visualization, assistance with software, and critical review of the final manuscript. AFA, SEA, SDK, DAR, AA, and MM were responsible for data collection, contributing to the writing of the original manuscript draft, and performing a critical review of the final manuscript. DBW, ABS, HNS, and AME contributed to study design and conceptualization, collective supervision over project tasks, administrative support, and performing a critical review of the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dihan, Q.A., Brown, A.D., Chauhan, M.Z. et al. Leveraging large language models to improve patient education on dry eye disease. Eye 39, 1115–1122 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-024-03476-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-024-03476-5

This article is cited by

-

Factors associated with the experience of AI tools for creating health education materials: cross-sectional study using an extended UTAUT model

BMC Medical Education (2026)

-

The role of large language models in improving the readability of orthopaedic spine patient educational material

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research (2025)