Abstract

A key research program within the meaning in life (MIL) literature aims to identify the key contributors to MIL. The experience of existential mattering, purpose in life and a sense of coherence are currently posited as three primary contributors to MIL. However, it is unclear whether they encompass all information people consider when judging MIL. Based on the ideas of classic and contemporary MIL scholars, the current research examines whether valuing one’s life experiences, or experiential appreciation, constitutes another unique contributor to MIL. Across seven studies, we find support for the idea that experiential appreciation uniquely predicts subjective judgements of MIL, even after accounting for the contribution of mattering, purpose and coherence to these types of evaluations. Overall, these findings support the hypothesis that valuing one’s experiences is uniquely tied to perceptions of meaning. Implications for the incorporation of experiential appreciation as a fundamental antecedent of MIL are discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data, full materials and supplementary analyses for studies 2–7 can be found in Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://osf.io/4yx9p/. See notes in OSF for access information for materials and data in study 1, as well as information about another large sample adult study (see ‘MIDUS Study’).

Code availability

As for data availability, all statistical code files including SPSS, Mplus and HLM are available in OSF at https://osf.io/4yx9p/.

References

Frankl, V. E. The Doctor and the Soul: from Psychotherapy to Logotherapy (Vintage, 1986).

Hicks, J. A. & King, L. A. Positive mood and social relatedness as information about meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271108 (2009).

Costin, V. & Vignoles, V. L. Meaning is about mattering: evaluating coherence, purpose, and existential mattering as precursors of meaning in life judgments. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000225 (2020).

George, L. S. & Park, C. L. The Multidimensional Existential Meaning Scale: a tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life. J. Posit. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1209546 (2017).

Martela, F. & Steger, M. F. The three meanings of meaning in life: distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. J. Posit. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623 (2016).

Steger, M. F., Frazier, P., Oishi, S. & Kaler, M. The meaning in life questionnaire: assessing the presence of and search for meaning in life. J. Couns. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.53.1.80 (2006).

Heintzelman, S. J. & King, L. A. Life is pretty meaningful. Am. Psychol. 69, 561–574 (2014).

Christy, A. G., Rivera, G., Chen, K. & Hicks, J. A. in Positive Psychology: Established and Emerging Issues (ed. Dunn, D. S.) 220–235 (Routledge, 2017).

Krause, N. Religious meaning and subjective well-being in late life. J. Gerontol. B https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/58.3.S160 (2003).

Reker, G. T., Peacock, E. J. & Wong, P. T. Meaning and purpose in life and well-being: a life-span perspective. J. Gerontol. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronj/42.1.44 (1987).

Ryff, C. D. & Keyes, C. L. M. The structure of psychological well-being revisited. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719 (1995).

Steger, M. F., & Kashdan, T. B. Stability and specificity of meaning in life and life satisfaction over one year. J. Happiness Stud. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9011-8 (2007).

Steger, M. F., Kawabata, Y., Shimai, S. & Otake, K. The meaningful life in Japan and the United States: levels and correlates of meaning in life. J. Res. Personal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.09.003 (2008).

Zika, S. & Chamberlain, K. On the relation between meaning in life and psychological well‐being. Br. J. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1992.tb02429.x (1992).

Harlow, L. L., Newcomb, M. D., & Bentler, P. M. Depression, self-derogation, substance use, and suicide ideation: lack of purpose in life as a mediational factor. J. Clin. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198601)42:1%3C5::AID-JCLP2270420102%3E3.0.CO;2-9 (1986).

Klinger, E. in The Human Quest for Meaning: a Handbook of Psychological Research and Clinical Applications (eds. Wong P. T. P. & Fry P. S.) 27–50 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1998).

Tanno, K. et al. Associations of ikigai as a positive psychological factor with all-cause mortality and cause-specific mortality among middle-aged and elderly Japanese people: findings from the Japan Collaborative Cohort Study. J. Psychosom. Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2008.10.018 (2009).

Baumeister, R. F. Meanings of Life (Guilford Press, 1991).

Battista, J. & Almond, R. The development of meaning in life. Psychiatry 36, 409–427 (1973).

Klinger, E. Meaning and Void: Inner Experience and the Incentives in People’s Lives (Univ. of Minnesota Press, 1977).

McKnight, P. E., & Kashdan, T. B. Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: an integrative, testable theory. Rev. Gen. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017152 (2009).

Wong, P. T. in Meaning in Positive and Existential Psychology (eds. Batthyany, A. & Russo-Netzer, P.) 149–184 (Springer, 2014).

de Muijnck, W. The meaning of lives and the meaning of things. J. Happiness Stud. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9382-y (2013).

Frankl, V. E. Logotherapy and existentialism. Psychother-Theor. Res. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0087982 (1967).

King, L. A. & Hicks, J. A. Detecting and constructing meaning in life events. J. Posit. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760902992316 (2009).

Heintzelman, S. J., Trent, J. & King, L. A. Encounters with objective coherence and the experience of meaning in life. Psychol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612465878 (2013).

Kim, J. & Hicks, J. A. Happiness begets children? Evidence for a bi-directional link between well-being and number of children. J. Posit. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1025420 (2016).

Nelson, S. K. et al. In defense of parenthood: children are associated with more joy than misery. Psychol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612447798 (2013).

Audi, R. Intrinsic value and meaningful life. Philos. Pap. https://doi.org/10.1080/05568640509485162 (2005).

King, L. A., Hicks, J. A., Krull, J. L. & Del Gaiso, A. K. Positive affect and the experience of meaning in life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.179 (2006).

Hicks, J. A. & King, L. A. Religious commitment and positive mood as information about meaning in life. J. Res. Personal. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2007.04.003 (2008).

Hicks, J. A. & King, L. A. Subliminal mere exposure and explicit and implicit positive affective responses. Cogn. Emot. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2010.497409 (2011).

Muthén, L. K. & Muthén, B. O. Mplus User’s Guide 8th edn (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2017).

Little, T. D., Rhemtulla, M., Gibson, K. & Schoemann, A. M. Why the items versus parcels controversy needn’t be one. Psychol. Method. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033266 (2013).

Rosenthal, R., Rosnow, R. L. & Rubin, D. B. Contrasts and Effect Sizes in Behavioral Research: a Correlational Approach (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2000).

Oishi, S., Lun, J., & Sherman, G. D. Residential mobility, self-concept, and positive affect in social interactions. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.1.131 (2007).

Hayes, A. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis (Guilford, 2018).

Preacher, K. J. & Hayes, A. F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 (2008).

Rivera, G. N., Vess, M., Hicks, J. A. & Routledge, C. Awe and meaning: elucidating complex effects of awe experiences on meaning in life. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2604 (2020).

Goodman, F. R., Disabato, D. J. & Kashdan, T. B. Reflections on unspoken problems and potential solutions for the well-being juggernaut in positive psychology. J. Posit. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1818815 (2020).

George, L. S. & Park, C. L. Are meaning and purpose distinct? An examination of correlates and predictors. J. Posit. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2013.805801 (2013).

Rosenberg, M. & McCullough, B. C. Mattering: inferred significance and mental health among adolescents. Res. Community Ment. Health 2, 163–182 (1981).

Carver, C. S. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: consider the brief COPE. Int. J. Behav. Med. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6 (1997).

Butler, J. & Kern, M. L. The PERMA-Profiler: a brief multidimensional measure of flourishing. Int. J. Wellbeing. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v6i3.526 (2016).

Aust, F., Diedenhofen, B., Ullrich, S. & Musch, J. Seriousness checks are useful to improve data validity in online research. Behav. Res. Methods. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-012-0265-2 (2013).

Schnell, T. The Sources of Meaning and Meaning in Life Questionnaire (SoMe): relations to demographics and well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903271074 (2009).

Frankl, V. E. Man’s Search for Meaning: an Introduction to Logotherapy (Pocket, 1963).

Weathers F. W. et al. PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5) (National Center for PTSD, 2013); www.ptsd.va.gov

Watson, D., Clark, L. A. & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063 (1988).

Costello, A. B. & Osborne, J. W. Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: four recommendations for getting the most from your analysis. Pract. Assess. Res. Evaluation. https://doi.org/10.7275/jyj1-4868 (2005).

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. Sociol. Method. Res. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124192021002005 (1992).

Brown, T. A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research (Guilford Press, 2015).

Hu, L. T. & Bentler, P. M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Modeling. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 (1999).

Byrne, B. M., Shavelson, R. J. & Muthén, B. Testing for the equivalence of factor covariance and mean structures: the issue of partial measurement invariance. Psychol. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.456 (1989).

Kray, L. J. et al. From what might have been to what must have been: counterfactual thinking creates meaning. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017905 (2010).

Heintzelman, S. J. & King, L. A. (The feeling of) meaning-as-information. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Rev. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868313518487 (2014).

Waytz, A., Hershfield, H. E. & Tamir, D. I. Mental simulation and meaning in life. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038322 (2015).

Valdesolo, P. & Graham, J. Awe, uncertainty, and agency detection. Psychol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613501884 (2014).

Piff, P. K. et al. Awe, the small self, and prosocial behavior. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000018 (2015).

Gordon, A. M. et al. The dark side of the sublime: distinguishing a threat-based variant of awe. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000120 (2017).

Rudd, M., Vohs, K. D. & Aaker, J. Awe expands people’s perception of time, alters decision making, and enhances well-being. Psychol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612438731 (2012).

McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A. & Tsang, J.-A. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112 (2002).

Heintzelman, S. J. & King, L. A. Routines and meaning in life. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167218795133 (2019).

Schlegel, R. J., Hicks, J. A., King, L. A. & Arndt, J. Feeling like you know who you are: perceived true self-knowledge and meaning in life. Person. Soc. Psychol. Bull. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211400424 (2011).

Acknowledgements

None of these studies were supported by funding sources. We thank B. Schmeichel, M. Vess and K. McLean for comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.A.H., P.H., Z.L., R.J.S., J.K. and F.M. contributed to the conception of the core research idea and at least one study design. J.A.H., P.H., R.J.S., J.K. and C.S. performed analysis and interpreted data. J.A.H., P.H., R.J.S., J.K., C.S. and F.M. prepared the manuscript. N.E. and D.F.C. collected and preprocessed the data from study 1. H.Z. collected and preprocessed the data from study 2, sample B. All authors approved the final version of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Vlad Costin and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Extended data

Extended Data Fig. 1 Meaning relevant coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic predicting global meaning in life in Study 1.

LA = Life appreciation.

Extended Data Fig. 2 Exploratory factor analysis: Rotated pattern matrix of experiential appreciation scale in Study 2.

Sample A: n = 469.

Extended Data Fig. 3 Bivariate correlations among study variables in Study 2.

MIL = meaning in life. EA = experiential appreciation. PA = positive affect. NA = negative affect. Correlation coefficients and descriptive statistics below the diagonal represent Sample A; those above the diagonal represent Sample B. All correlation coefficients are statistically significant at p < .001, except for the correlations between COVID-19-related stress and purpose at p = .006, and PA at p = .001 and the correlation between EA and NA at p = .032 for Sample B.

Extended Data Fig. 4 Within-person correlations between study variables in Study 3.

MIL = meaning in life. EA = experiential appreciation. PA = positive affect. NA = negative affect.

Extended Data Fig. 5

Examples of meaningful experiences rated high in experiential appreciation and relatively low in mattering, purpose, and coherence in Study 4.

Extended Data Fig. 6 Bivariate correlations among key variables in Study 5.

MIL = meaning in life. EA = experiential appreciation. PA = positive affect. NA = negative affect. All correlation coefficients are statistically significant at p < .001, except for the correlation between small self and global MIL at p < .01, and the non-significant correlation between PA and small self.

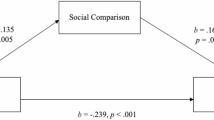

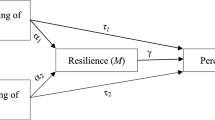

Extended Data Fig. 7 Conceptual model for indirect effects of awe induction on meaning in life.

a, Experiential aprreciation, small Self, and positive affect as mediators. b, Experiential aprreciation and tripartite components of meaning as mediators. The latter model and its modified one were used in Studies 5 and 6.

Extended Data Fig. 8 Bivariate correlations among key variables in Study 6.

MIL = meaning in life. EA = experiential appreciation. PA = positive affect. All correlation coefficients are statistically significant at p < .001, except for the correlation between small self and global MIL, small self and mattering, and small self and purpose at p < .01, and the non-significant correlations between small self and EA and PA and small self.

Extended Data Fig. 9 Bivariate correlations among key variables in Study 7.

MIL = meaning in life. EA = experiential appreciation. PA = positive affect. NA = negative affect. All correlation coefficients are statistically significant at p < .001, except for the correlation between NA and mattering, vividness and EA, and vividness and PA at p < .01, the correlation between vividness and mattering at p < .05, and the non-significant correlation between NA and EA.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, J., Holte, P., Martela, F. et al. Experiential appreciation as a pathway to meaning in life. Nat Hum Behav 6, 677–690 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01283-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01283-6

This article is cited by

-

The Overlooked Self-Transcendent Nature of Meaning in Life: Having a Positive Impact on Others

Journal of Happiness Studies (2026)

-

Beyond Suffering: Existential Positive Psychology as a Framework for Centering Meaning in Addiction Treatment

International Journal of Applied Positive Psychology (2025)

-

Cancer patients’ perceptions of the meaning in life: a qualitative meta-synthesis

Supportive Care in Cancer (2025)

-

Creating Kinship with Nature and Boosting Well-Being: Testing Two Novel Character Strengths-Based Nature Connectedness Interventions

Journal of Happiness Studies (2025)

-

Meaning-augmentation motive: Valuing meaning in life facilitates preference for experiential over material purchases

Motivation and Emotion (2025)