Abstract

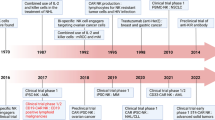

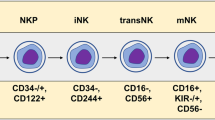

Natural killer (NK) cells comprise a unique population of innate lymphoid cells endowed with intrinsic abilities to identify and eliminate virally infected cells and tumour cells. Possessing multiple cytotoxicity mechanisms and the ability to modulate the immune response through cytokine production, NK cells play a pivotal role in anticancer immunity. This role was elucidated nearly two decades ago, when NK cells, used as immunotherapeutic agents, showed safety and efficacy in the treatment of patients with advanced-stage leukaemia. In recent years, following the paradigm-shifting successes of chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered adoptive T cell therapy and the advancement in technologies that can turn cells into powerful antitumour weapons, the interest in NK cells as a candidate for immunotherapy has grown exponentially. Strategies for the development of NK cell-based therapies focus on enhancing NK cell potency and persistence through co-stimulatory signalling, checkpoint inhibition and cytokine armouring, and aim to redirect NK cell specificity to the tumour through expression of CAR or the use of engager molecules. In the clinic, the first generation of NK cell therapies have delivered promising results, showing encouraging efficacy and remarkable safety, thus driving great enthusiasm for continued innovation. In this Review, we describe the various approaches to augment NK cell cytotoxicity and longevity, evaluate challenges and opportunities, and reflect on how lessons learned from the clinic will guide the design of next-generation NK cell products that will address the unique complexities of each cancer.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Maude, S. L. et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 439–448 (2018).

Schuster, S. J. et al. Tisagenlecleucel in adult relapsed or refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 45–56 (2019).

Neelapu, S. S. et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 2531–2544 (2017).

Park, J. H. et al. Long-term follow-up of CD19 CAR therapy in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 449–459 (2018).

June, C. H., O’Connor, R. S., Kawalekar, O. U., Ghassemi, S. & Milone, M. C. CAR T cell immunotherapy for human cancer. Science 359, 1361–1365 (2018).

Wang, M. et al. KTE-X19 CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 1331–1342 (2020).

Munshi, N. C. et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 705–716 (2021).

Raje, N. et al. Anti-BCMA CAR T-cell therapy bb2121 in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 1726–1737 (2019).

Melenhorst, J. J. et al. Decade-long leukaemia remissions with persistence of CD4+ CAR T cells. Nature 602, 503–509 (2022). This landmark article reports the sustained remissions and in vivo persistence of CD19-CAR T cells for more than 10 years after infusion, and hence highlights the long-term durability of clinical responses achieved using genetically engineered T cells.

Malmberg, K.-J. et al. Natural killer cell-mediated immunosurveillance of human cancer. Semin. Immunol. 31, 20–29 (2017).

Lanier, L. L. Up on the tightrope: natural killer cell activation and inhibition. Nat. Immunol. 9, 495–502 (2008).

Joncker, N. T., Fernandez, N. C., Treiner, E., Vivier, E. & Raulet, D. H. NK cell responsiveness is tuned commensurate with the number of inhibitory receptors for self-MHC class I: the rheostat model. J. Immunol. 182, 4572–4580 (2009). This study elucidates the nature of NK cell responsiveness, which relies on the integration of both inhibitory and activating signalling cues to ensure self-tolerance and immunosurveillance over abnormal cells.

Joncker, N. T., Shifrin, N., Delebecque, F. & Raulet, D. H. Mature natural killer cells reset their responsiveness when exposed to an altered MHC environment. J. Exp. Med. 207, 2065–2072 (2010).

Burshtyn, D. N. et al. Recruitment of tyrosine phosphatase HCP by the killer cell inhibitor receptor. Immunity 4, 77–85 (1996).

Yokoyama, W. M. & Kim, S. How do natural killer cells find self to achieve tolerance? Immunity 24, 249–257 (2006).

Brodin, P., Lakshmikanth, T., Johansson, S., Kärre, K. & Höglund, P. The strength of inhibitory input during education quantitatively tunes the functional responsiveness of individual natural killer cells. Blood 113, 2434–2441 (2009).

Imai, K., Matsuyama, S., Miyake, S., Suga, K. & Nakachi, K. Natural cytotoxic activity of peripheral-blood lymphocytes and cancer incidence: an 11-year follow-up study of a general population. Lancet 356, 1795–1799 (2000).

Guerra, N. et al. NKG2D-deficient mice are defective in tumor surveillance in models of spontaneous malignancy. Immunity 28, 571–580 (2008).

López-Soto, A., Gonzalez, S., Smyth, M. J. & Galluzzi, L. Control of metastasis by NK cells. Cancer Cell 32, 135–154 (2017).

Abel, A. M., Yang, C., Thakar, M. S. & Malarkannan, S. Natural killer cells: development, maturation, and clinical utilization. Front. Immunol. 9, 1869 (2018).

Dalle, J.-H. et al. Characterization of cord blood natural killer cells: implications for transplantation and neonatal infections. Pediatr. Res. 57, 649–655 (2005).

Strauss-Albee, D. M. et al. Human NK cell repertoire diversity reflects immune experience and correlates with viral susceptibility. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 297ra115–297ra115 (2015).

Prager, I. & Watzl, C. Mechanisms of natural killer cell-mediated cellular cytotoxicity. J. Leukoc. Biol. 105, 1319–1329 (2019).

Wang, W., Erbe, A. K., Hank, J. A., Morris, Z. S. & Sondel, P. M. NK cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. 6, 368 (2015).

O’Leary, J. G., Goodarzi, M., Drayton, D. L. & von Andrian, U. H. T cell- and B cell-independent adaptive immunity mediated by natural killer cells. Nat. Immunol. 7, 507–516 (2006). This seminal study demonstrates that NK cells can mediate durable recall responses upon antigen re-exposure, establishing the concept of NK cell adaptive memory.

Sun, J. C., Beilke, J. N. & Lanier, L. L. Adaptive immune features of natural killer cells. Nature 457, 557–561 (2009). This important article reveals self-renewing ‘memory’ NK cell subsets that can undergo secondary expansion and elicit strong adaptive immune responses upon viral challenge when transferred to naive animals.

Cooper, M. A. et al. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 1915–1919 (2009). This work pioneers the concept of cytokine-induced memory-like NK cells which elicit robust recall responses when transferred to naïve hosts.

Romee, R. et al. Cytokine activation induces human memory-like NK cells. Blood 120, 4751–4760 (2012).

Romee, R. et al. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells exhibit enhanced responses against myeloid leukemia. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 357ra123 (2016).

Shapiro, R. M. et al. Expansion, persistence, and efficacy of donor memory-like NK cells infused for post-transplant relapse. J. Clin. Investig. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI154334 (2022).

Platonova, S. et al. Profound coordinated alterations of intratumoral NK cell phenotype and function in lung carcinoma. Cancer Res. 71, 5412–5422 (2011).

Sun, C. et al. High NKG2A expression contributes to NK cell exhaustion and predicts a poor prognosis of patients with liver cancer. Oncoimmunology 6, e1264562 (2017).

Spanholtz, J. et al. High log-scale expansion of functional human natural killer cells from umbilical cord blood CD34-positive cells for adoptive cancer immunotherapy. PLoS ONE 5, e9221 (2010).

Dolstra, H. et al. Successful transfer of umbilical cord blood CD34+ hematopoietic stem and progenitor-derived NK cells in older acute myeloid leukemia patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 4107–4118 (2017).

Liu, E. et al. Cord blood NK cells engineered to express IL-15 and a CD19-targeted CAR show long-term persistence and potent antitumor activity. Leukemia 32, 520–531 (2018). This article reports the first successful clinical application of CAR-modified NK immunotherapy in patients with CD19-positive haematologic malignancies.

Berrien-Elliott, M. M. et al. Multidimensional analyses of donor memory-like NK cells reveal new associations with response after adoptive immunotherapy for leukemia. Cancer Discov. 10, 1854–1871 (2020).

Liu, E. et al. Use of CAR-transduced natural killer cells in CD19-positive lymphoid tumors. N. Engl. J. Med. 382, 545–553 (2020).

Gong, J.-H., Maki, G. & Klingemann, H. G. Characterization of a human cell line (NK-92) with phenotypical and functional characteristics of activated natural killer cells. Leukemia 8, 652–658 (1994).

Tang, X. et al. First-in-man clinical trial of CAR NK-92 cells: safety test of CD33-CAR NK-92 cells in patients with relapsed and refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Am. J. Cancer Res. 8, 1083–1089 (2018).

Zhang, C. et al. Chimeric antigen receptor-engineered NK-92 cells: an off-the-shelf cellular therapeutic for targeted elimination of cancer cells and induction of protective antitumor immunity. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2017.00533 (2017).

Hoogstad-van Evert, J. S. et al. Umbilical cord blood CD34+ progenitor-derived NK cells efficiently kill ovarian cancer spheroids and intraperitoneal tumors in NOD/SCID/IL2Rgnull mice. Oncoimmunology 6, e1320630 (2017).

Knorr, D. A. et al. Clinical-scale derivation of natural killer cells from human pluripotent stem cells for cancer therapy. Stem Cell Transl. Med. 2, 274–283 (2013).

Li, Y., Hermanson, D. L., Moriarity, B. S. & Kaufman, D. S. Human iPSC-derived natural killer cells engineered with chimeric antigen receptors enhance anti-tumor activity. Cell Stem Cell 23, 181–192.e5 (2018). This article demonstrates the first successful generation of iPSC-derived CAR NK cells.

Goldenson, B. H. et al. Umbilical cord blood and iPSC-derived natural killer cells demonstrate key differences in cytotoxic activity and KIR profiles. Front. Immunol. 11, https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.561553 (2020).

Zhu, H. et al. Pluripotent stem cell-derived NK cells with high-affinity noncleavable CD16a mediate improved antitumor activity. Blood 135, 399–410 (2020).

Kim, K. et al. Epigenetic memory in induced pluripotent stem cells. Nature 467, 285–290 (2010).

Bar-Nur, O., Russ, H. A., Efrat, S. & Benvenisty, N. Epigenetic memory and preferential lineage-specific differentiation in induced pluripotent stem cells derived from human pancreatic islet β cells. Cell Stem Cell 9, 17–23 (2011).

Goodridge, J. P. et al. FT596: translation of first-of-kind multi-antigen targeted off-the-shelf CAR-NK cell with engineered persistence for the treatment of B cell malignancies. Blood 134, 301–301 (2019).

Bachanova, V. et al. Safety and efficacy of FT596, a first-in-class, multi-antigen targeted, off-the-shelf, iPSC-derived CD19 CAR NK cell therapy in relapsed/refractory B-cell lymphoma. Blood 138, 823 (2021).

Goodridge, J. P. et al. Abstract 1550: FT576 path to first-of-kind clinical trial: translation of a versatile multi-antigen specific off-the-shelf NK cell for treatment of multiple myeloma. Cancer Res. 81, 1550 (2021).

Strati, P. et al. Preliminary results of a phase I trial of FT516, an off-the-shelf natural killer (NK) cell therapy derived from a clonal master induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line expressing high-affinity, non-cleavable CD16 (hnCD16), in patients (pts) with relapsed/refractory (R/R) B-cell lymphoma (BCL). J. Clin. Oncol. 39, 7541–7541 (2021).

Imai, C., Iwamoto, S. & Campana, D. Genetic modification of primary natural killer cells overcomes inhibitory signals and induces specific killing of leukemic cells. Blood 106, 376–383 (2005). This article describes the first successful generation of CAR NK cells using a 41BB-co-stimulated CD19-directed synthetic CAR.

Ruggeri, L. et al. Effectiveness of donor natural killer cell alloreactivity in mismatched hematopoietic transplants. Science 295, 2097–2100 (2002). This seminal work demonstrates that alloreactive NK cells confer a potent graft-versus-leukaemia effect and protect against GvHD in recipients of T cell-depleted HLA-haploidentical allogeneic transplantation (TCD-haplo-alloHSCT).

Ruggeri, L. et al. Role of natural killer cell alloreactivity in HLA-mismatched hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood 94, 333–339 (1999).

Davies, S. M. et al. Evaluation of KIR ligand incompatibility in mismatched unrelated donor hematopoietic transplants. Killer immunoglobulin-like receptor. Blood 100, 3825–3827 (2002).

Ruggeri, L. et al. Donor natural killer cell allorecognition of missing self in haploidentical hematopoietic transplantation for acute myeloid leukemia: challenging its predictive value. Blood 110, 433–440 (2007).

Ciurea, S. O. et al. Decrease post-transplant relapse using donor-derived expanded NK-cells. Leukemia 36, 155–164 (2022).

Hsu, K. C. et al. Improved outcome in HLA-identical sibling hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia predicted by KIR and HLA genotypes. Blood 105, 4878–4884 (2005).

Verheyden, S., Schots, R., Duquet, W. & Demanet, C. A defined donor activating natural killer cell receptor genotype protects against leukemic relapse after related HLA-identical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Leukemia 19, 1446–1451 (2005).

Venstrom, J. M. et al. HLA-C-dependent prevention of leukemia relapse by donor activating KIR2DS1. N. Engl. J. Med. 367, 805–816 (2012).

Boudreau, J. E. et al. KIR3DL1/HLA-B subtypes govern acute myelogenous leukemia relapse after hematopoietic cell transplantation. J. Clin. Oncol. 35, 2268 (2017).

Schetelig, J. et al. External validation of models for KIR2DS1/KIR3DL1-informed selection of hematopoietic cell donors fails. Blood 135, 1386–1395 (2020).

Beelen, D. W. et al. Genotypic inhibitory killer immunoglobulin-like receptor ligand incompatibility enhances the long-term antileukemic effect of unmodified allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in patients with myeloid leukemias. Blood 105, 2594–2600 (2005).

Bishara, A. et al. The beneficial role of inhibitory KIR genes of HLA class I NK epitopes in haploidentically mismatched stem cell allografts may be masked by residual donor-alloreactive T cells causing GVHD. Tissue Antigens 63, 204–211 (2004).

Schaffer, M., Malmberg, K. J., Ringdén, O., Ljunggren, H. G. & Remberger, M. Increased infection-related mortality in KIR-ligand-mismatched unrelated allogeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. Transplantation 78, 1081–1085 (2004).

Mehta, R. S. & Rezvani, K. Can we make a better match or mismatch with KIR genotyping? Hematol. Am. Soc. Hematol. Educ. Program. 2016, 106–118 (2016).

Schmidts, A. et al. Rational design of a trimeric APRIL-based CAR-binding domain enables efficient targeting of multiple myeloma. Blood Adv. 3, 3248–3260 (2019).

Leivas, A. et al. NKG2D-CAR-transduced natural killer cells efficiently target multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 11, 146 (2021).

Chang, Y. H. et al. A chimeric receptor with NKG2D specificity enhances natural killer cell activation and killing of tumor cells. Cancer Res. 73, 1777–1786 (2013).

Biederstädt, A. & Rezvani, K. Engineering the next generation of CAR-NK immunotherapies. Int. J. Hematol. 114, 554–571 (2021).

Daher, M. & Rezvani, K. Outlook for new CAR-based therapies with a focus on CAR NK cells: what lies beyond CAR-engineered T cells in the race against cancer. Cancer Disco 11, 45–58 (2021).

Lanier, L. L., Corliss, B. C., Wu, J., Leong, C. & Phillips, J. H. Immunoreceptor DAP12 bearing a tyrosine-based activation motif is involved in activating NK cells. Nature 391, 703–707 (1998). This seminal article elucidates the role of DAP12 as an activating NK cell immunoreceptor through cross-linking with killer cell immunoglobin-like receptor (KIR) family molecules.

Zhao, R. et al. DNAX-activating protein 10 co-stimulation enhances the anti-tumor efficacy of chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Oncoimmunology 8, e1509173 (2018).

Ng, Y. Y. et al. T cells expressing NKG2D CAR with a DAP12 signaling domain stimulate lower cytokine production while effective in tumor eradication. Mol. Ther. 29, 75–85 (2021).

Töpfer, K. et al. DAP12-based activating chimeric antigen receptor for NK cell tumor immunotherapy. J. Immunol. 194, 3201 (2015).

Billadeau, D. D., Upshaw, J. L., Schoon, R. A., Dick, C. J. & Leibson, P. J. NKG2D-DAP10 triggers human NK cell-mediated killing via a Syk-independent regulatory pathway. Nat. Immunol. 4, 557–564 (2003). This article uncovers the role of the activating NKG2D–DAP10 immune receptor recognition complex which can induce NK cell-mediated killing in a SYK-independent manner.

Frigault, M. J. et al. Identification of chimeric antigen receptors that mediate constitutive or inducible proliferation of T cells. Cancer Immunol. Res. 3, 356–367 (2015).

Long, A. H. et al. 4-1BB costimulation ameliorates T cell exhaustion induced by tonic signaling of chimeric antigen receptors. Nat. Med. 21, 581–590 (2015). This important article lays out the principle of antigen-independent tonic CAR signalling which can induce T cell exhaustion impairing antitumour efficacy.

Watanabe, N. et al. Fine-tuning the CAR spacer improves T-cell potency. Oncoimmunology 5, e1253656 (2016).

Mamonkin, M. et al. Tonic 4-1BB signaling from chimeric antigen receptors (CARs) impairs expansion of T cells due to Fas-mediated apoptosis. J. Immunol. 196 (Suppl 1), 143.7 (2016).

Feucht, J. et al. Calibration of CAR activation potential directs alternative T cell fates and therapeutic potency. Nat. Med. 25, 82–88 (2019).

Bridgeman, J. S. et al. CD3ζ-based chimeric antigen receptors mediate T cell activation via cis- and trans-signalling mechanisms: implications for optimization of receptor structure for adoptive cell therapy. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 175, 258–267 (2014).

Bridgeman, J. S. et al. The optimal antigen response of chimeric antigen receptors harboring the CD3ζ transmembrane domain is dependent upon incorporation of the receptor into the endogenous TCR/CD3 complex. J. Immunol. 184, 6938–6949 (2010).

Muller, Y. D. et al. The CD28-transmembrane domain mediates chimeric antigen receptor heterodimerization with CD28. Front. Immunol. 12, 639818 (2021).

Savoldo, B. et al. CD28 costimulation improves expansion and persistence of chimeric antigen receptor-modified T cells in lymphoma patients. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 1822–1826 (2011).

Cronk, R. J., Zurko, J. & Shah, N. N. Bispecific chimeric antigen receptor T cell therapy for B cell malignancies and multiple myeloma. Cancers 12, 2523 (2020).

Zah, E. et al. Systematically optimized BCMA/CS1 bispecific CAR-T cells robustly control heterogeneous multiple myeloma. Nat. Commun. 11, 2283 (2020).

Shah, N. N. et al. Bispecific anti-CD20, anti-CD19 CAR T cells for relapsed B cell malignancies: a phase 1 dose escalation and expansion trial. Nat. Med. 26, 1569–1575 (2020).

Wallstabe, L. et al. ROR1-CAR T cells are effective against lung and breast cancer in advanced microphysiologic 3D tumor models. JCI Insight https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.126345 (2019).

Srivastava, S. et al. Logic-gated ROR1 chimeric antigen receptor expression rescues T cell-mediated toxicity to normal tissues and enables selective tumor targeting. Cancer Cell 35, 489–503.e8 (2019).

Cho, J. H. et al. Engineering advanced logic and distributed computing in human CAR immune cells. Nat. Commun. 12, 792 (2021).

Garrison, B. S. et al. FLT3 OR CD33 NOT EMCN logic gated CAR-NK cell therapy (SENTI-202) for precise targeting of AML. Blood 138 (suppl. 1), 2799 (2021).

Gonzalez, A. et al. Abstract LB028: Development of logic-gated CAR-NK cells to reduce target-mediated healthy tissue toxicities. Cancer Res. 81, LB028 (2021).

Mensali, N. et al. NK cells specifically TCR-dressed to kill cancer cells. EBioMedicine 40, 106–117 (2019).

Shao, H. et al. TCR mispairing in genetically modified T cells was detected by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Mol. Biol. Rep. 37, 3951–3956 (2010).

Wiernik, A. et al. Targeting natural killer cells to acute myeloid leukemia in vitro with a CD16×33 bispecific killer cell engager and ADAM17 inhibition. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 3844–3855 (2013).

Vallera, D. A. et al. Heterodimeric bispecific single-chain variable-fragment antibodies against EpCAM and CD16 induce effective antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against human carcinoma cells. Cancer Biother. Radiopharm. 28, 274–282 (2013).

Gleason, M. K. et al. CD16xCD33 bispecific killer cell engager (BiKE) activates NK cells against primary MDS and MDSC CD33+ targets. Blood 123, 3016–3026 (2014).

Schmohl, J., Gleason, M., Dougherty, P., Miller, J. S. & Vallera, D. A. Heterodimeric bispecific single chain variable fragments (scFv) killer engagers (BiKEs) enhance NK-cell activity against CD133+ colorectal cancer cells. Target. Oncol. 11, 353–361 (2016).

Kerbauy, L. N. et al. Combining AFM13, a bispecific CD30/CD16 antibody, with cytokine-activated blood and cord blood-derived NK cells facilitates CAR-like responses against CD30+ malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 3744–3756 (2021).

Reusch, U. et al. A novel tetravalent bispecific TandAb (CD30/CD16A) efficiently recruits NK cells for the lysis of CD30+ tumor cells. MAbs 6, 727–738 (2014).

Schmohl, J. U. et al. Tetraspecific scFv construct provides NK cell mediated ADCC and self-sustaining stimuli via insertion of IL-15 as a cross-linker. Oncotarget 7, 73830–73844 (2016).

Vallera, D. A. et al. IL15 trispecific killer engagers (TriKE) make natural killer cells specific to CD33+ targets while also inducing persistence, in vivo expansion, and enhanced function. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 3440–3450 (2016).

Schmohl, J. U. et al. Engineering of anti-CD133 trispecific molecule capable of inducing NK expansion and driving antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Cancer Res. Treat. 49, 1140 (2017).

Arvindam, U. S. et al. A trispecific killer engager molecule against CLEC12A effectively induces NK-cell mediated killing of AML cells. Leukemia 35, 1586–1596 (2021).

Gauthier, L. et al. Multifunctional natural killer cell engagers targeting NKp46 trigger protective tumor immunity. Cell 177, 1701–1713.e16 (2019). This report outlines a novel tri-specific NK cell engager molecule that cross-links the two NK cell activating receptors CD16 and NKp46 with a specific tumour antigen.

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04074746 (2020).

Bryceson, Y. T., March, M. E., Ljunggren, H. G. & Long, E. O. Synergy among receptors on resting NK cells for the activation of natural cytotoxicity and cytokine secretion. Blood 107, 159–166 (2006).

Rosario, M. et al. The IL-15-based ALT-803 complex enhances FcγRIIIa-triggered NK cell responses and in vivo clearance of B cell lymphomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 596–608 (2016).

de Rham, C. et al. The proinflammatory cytokines IL-2, IL-15 and IL-21 modulate the repertoire of mature human natural killer cell receptors. Arthritis Res. Ther. 9, R125 (2007).

Gang, M. et al. CAR-modified memory-like NK cells exhibit potent responses to NK-resistant lymphomas. Blood 136, 2308–2318 (2020).

Dong, H. et al. Engineered memory-like NK cars targeting a neoepitope derived from intracellular NPM1c exhibit potent activity and specificity against acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 136, 3–4 (2020).

Lasek, W., Zagożdżon, R. & Jakobisiak, M. Interleukin 12: still a promising candidate for tumor immunotherapy? Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 63, 419–435 (2014).

McMichael, E. L. et al. IL-21 enhances natural killer cell response to cetuximab-coated pancreatic tumor cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 23, 489–502 (2017).

Miller, J. S. Therapeutic applications: natural killer cells in the clinic. Hematology 2013, 247–253 (2013).

Anton, O. M. et al. Trans-endocytosis of intact IL-15Rα–IL-15 complex from presenting cells into NK cells favors signaling for proliferation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 522–531 (2020).

Tarannum, M. & Romee, R. Cytokine-induced memory-like natural killer cells for cancer immunotherapy. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 12, 592 (2021).

Felices, M. et al. Continuous treatment with IL-15 exhausts human NK cells via a metabolic defect. JCI Insight https://doi.org/10.1172/jci.insight.96219 (2018).

Sarhan, D. et al. Adaptive NK cells resist regulatory T-cell suppression driven by IL37. Cancer Immunol. Res. 6, 766–775 (2018).

Nuñez, S. Y. et al. Human M2 macrophages limit NK cell effector functions through secretion of TGF-β and engagement of CD85j. J. Immunol. 200, 1008–1015 (2018).

Tumino, N. et al. Interaction between MDSC and NK cells in solid and hematological malignancies: impact on HSCT. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.638841 (2021).

Zalfa, C. & Paust, S. Natural killer cell interactions with myeloid derived suppressor cells in the tumor microenvironment and implications for cancer immunotherapy. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.633205 (2021).

Ni, J. et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing of tumor-infiltrating NK cells reveals that inhibition of transcription factor HIF-1α unleashes NK cell activity. Immunity 52, 1075–1087.e8 (2020).

Van Wilpe, S. et al. Lactate dehydrogenase: a marker of diminished antitumor immunity. Oncoimmunology 9, 1731942 (2020).

Cascone, T. et al. Increased tumor glycolysis characterizes immune resistance to adoptive T cell therapy. Cell Metab. 27, 977–-987.e4 (2018).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01791595 (2013).

Jin, D. et al. CD73 on tumor cells impairs antitumor T-cell responses: a novel mechanism of tumor-induced immune suppression. Cancer Res. 70, 2245–2255 (2010).

Stagg, J. et al. Anti-CD73 antibody therapy inhibits breast tumor growth and metastasis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 1547–1552 (2010).

Allard, B., Longhi, M. S., Robson, S. C. & Stagg, J. The ectonucleotidases CD39 and CD73: novel checkpoint inhibitor targets. Immunol. Rev. 276, 121–144 (2017).

Perrot, I. et al. Blocking antibodies targeting the CD39/CD73 immunosuppressive pathway unleash immune responses in combination cancer therapies. Cell Rep. 27, 2411–2425.e9 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04148937 (2020).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03454451 (2018).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03616886 (2018).

Young, A. et al. Co-inhibition of CD73 and A2AR adenosine signaling improves anti-tumor immune responses. Cancer Cell 30, 391–403 (2016).

Young, A. et al. A2AR adenosine signaling suppresses natural killer cell maturation in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 78, 1003 (2018).

Lupo, K. & Matosevic, S. 123 Natural killer cells engineered with an inducible, responsive genetic construct targeting TIGIT and CD73 to relieve immunosuppression within the GBM microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 8, A74–A75 (2020).

Giuffrida, L. et al. CRISPR/Cas9 mediated deletion of the adenosine A2A receptor enhances CAR T cell efficacy. Nat. Commun. 12, 3236 (2021).

Kim, T.-D. et al. Human microRNA-27a* targets Prf1 and GzmB expression to regulate NK-cell cytotoxicity. Blood, J. Am. Soc. Hematol. 118, 5476–5486 (2011).

Yvon, E. S. et al. Cord blood natural killer cells expressing a dominant negative TGF-β receptor: implications for adoptive immunotherapy for glioblastoma. Cytotherapy 19, 408–418 (2017).

Daher, M. et al. The TGF-β/SMAD signaling pathway as a mediator of NK cell dysfunction and immune evasion in myelodysplastic syndrome. Blood 130, 53–53 (2017).

Shaim, H. et al. Targeting the αv integrin/TGF-β axis improves natural killer cell function against glioblastoma stem cells. J. Clin. Investig. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI142116 (2021).

Stojanovic, A., Fiegler, N., Brunner-Weinzierl, M. & Cerwenka, A. CTLA-4 Is expressed by activated mouse NK cells and inhibits NK cell IFN-γ production in response to mature dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 192, 4184–4191 (2014).

Russick, J. et al. Natural killer cells in the human lung tumor microenvironment display immune inhibitory functions. J. Immunother. Cancer 8, e001054 (2020).

Sanseviero, E. et al. Anti-CTLA-4 activates intratumoral NK cells and combined with IL15/IL15Rα complexes enhances tumor control. Cancer Immunol. Res. 7, 1371–1380 (2019).

Judge, S. J. et al. Minimal PD-1 expression in mouse and human NK cells under diverse conditions. J. Clin. Investig. 130, 3051–3068 (2020).

Judge, S. J., Murphy, W. J. & Canter, R. J. Characterizing the dysfunctional NK cell: assessing the clinical relevance of exhaustion, anergy, and senescence. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 10, 49–49 (2020).

Davis, Z. et al. Low-density PD-1 expression on resting human natural killer cells is functional and upregulated after transplantation. Blood Adv. 5, 1069–1080 (2021).

Hsu, J. et al. Contribution of NK cells to immunotherapy mediated by PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. J. Clin. Investig. 128, 4654–4668 (2018).

Dong, W. et al. The mechanism of anti-PD-L1 antibody efficacy against PD-L1-negative tumors identifies NK cells expressing PD-L1 as a cytolytic effector. Cancer Discov. 9, 1422–1437 (2019).

Newman, J. & Horowitz, A. NK cells seize PD1 from leukaemia cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 21, 345–345 (2021).

Wilk, A. J. et al. A single-cell atlas of the peripheral immune response in patients with severe COVID-19. Nat. Med. 26, 1070–1076 (2020).

da Silva, I. P. et al. Reversal of NK-cell exhaustion in advanced melanoma by Tim-3 blockade. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2, 410–422 (2014).

Farkas, A. M. et al. Tim-3 and TIGIT mark natural killer cells susceptible to effector dysfunction in human bladder cancer. J. Immunol. 200, 124.114 (2018).

Chauvin, J.-M. et al. IL15 stimulation with TIGIT blockade reverses CD155-mediated NK-cell dysfunction in melanoma. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 5520–5533 (2020).

Sarhan, D. et al. Adaptive NK cells with low TIGIT expression are inherently resistant to myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Res. 76, 5696–5706 (2016).

Zhang, Q. et al. Blockade of the checkpoint receptor TIGIT prevents NK cell exhaustion and elicits potent anti-tumor immunity. Nat. Immunol. 19, 723–732 (2018).

Ali, A. et al. LAG-3 modulation of natural killer cell immunoregulatory function. J. Immunol. 202, 76.77 (2019).

Kohrt, H. E. et al. Anti-KIR antibody enhancement of anti-lymphoma activity of natural killer cells as monotherapy and in combination with anti-CD20 antibodies. Blood 123, 678–686 (2014).

Vey, N. et al. Randomized phase 2 trial of Lirilumab (anti-KIR monoclonal antibody, mAb) as maintenance treatment in elderly patients (pts) with acute myeloid leukemia (AML): results of the Effikir trial. Blood 130, 889–889 (2017).

Vey, N. et al. A phase 1 study of Lirilumab (antibody against killer immunoglobulin-like receptor antibody KIR2D; IPH2102) in patients with solid tumors and hematologic malignancies. Oncotarget 9, 17675–17688 (2018).

Kim, S. et al. Licensing of natural killer cells by host major histocompatibility complex class I molecules. Nature 436, 709–713 (2005). This seminal work lays out the concept of NK cell ‘licensing’ through which NK cells acquire functional competence and self-tolerance by interaction of inhibitory receptors and self-MHC molecules.

Kim, S. et al. HLA alleles determine differences in human natural killer cell responsiveness and potency. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 3053–3058 (2008).

André, P. et al. Anti-NKG2A mAb is a checkpoint inhibitor that promotes anti-tumor immunity by unleashing both T and NK cells. Cell 175, 1731–1743.e13 (2018).

Kamiya, T., Seow, S. V., Wong, D., Robinson, M. & Campana, D. Blocking expression of inhibitory receptor NKG2A overcomes tumor resistance to NK cells. J. Clin. Investig. 129, 2094–2106 (2019).

Delconte, R. B. et al. CIS is a potent checkpoint in NK cell–mediated tumor immunity. Nat. Immunol. 17, 816–824 (2016). This important article identifies the intracellular NK cell checkpoint CIS, which negatively regulates IL-15 signalling.

Delconte, R. B. et al. NK cell priming from endogenous homeostatic signals is modulated by CIS. Front. Immunol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.00075 (2020).

Daher, M. et al. Targeting a cytokine checkpoint enhances the fitness of armored cord blood CAR-NK cells. Blood 137, 624–636 (2021).

Zhu, H. et al. Metabolic reprograming via deletion of CISH in human iPSC-derived NK cells promotes in vivo persistence and enhances anti-tumor activity. Cell Stem Cell 27, 224–237.e6 (2020).

Coca, S. et al. The prognostic significance of intratumoral natural killer cells in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Cancer 79, 2320–2328 (1997).

Ishigami, S. et al. Prognostic value of intratumoral natural killer cells in gastric carcinoma. Cancer 88, 577–583 (2000).

Villegas, F. R. et al. Prognostic significance of tumor infiltrating natural killer cells subset CD57 in patients with squamous cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 35, 23–28 (2002).

Donskov, F. & von der Maase, H. Impact of immune parameters on long-term survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 1997–2005 (2006).

Geissler, K. et al. Immune signature of tumor infiltrating immune cells in renal cancer. Oncoimmunology 4, e985082 (2015).

Wendel, M., Galani, I. E., Suri-Payer, E. & Cerwenka, A. Natural killer cell accumulation in tumors is dependent on IFN-γ and CXCR3 ligands. Cancer Res. 68, 8437–8445 (2008).

Mlecnik, B. et al. Biomolecular network reconstruction identifies T-cell homing factors associated with survival in colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology 138, 1429–1440 (2010).

Park, M. H., Lee, J. S. & Yoon, J. H. High expression of CX3CL1 by tumor cells correlates with a good prognosis and increased tumor-infiltrating CD8+ T cells, natural killer cells, and dendritic cells in breast carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 106, 386–392 (2012).

Castriconi, R. et al. Molecular mechanisms directing migration and retention of natural killer cells in human tissues. Front. Immunol. 9, 2324 (2018).

Levy, E. R., Clara, J. A., Reger, R. N., Allan, D. S. J. & Childs, R. W. RNA-seq analysis reveals CCR5 as a key target for CRISPR gene editing to regulate in vivo NK cell trafficking. Cancers https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers13040872 (2021).

Wennerberg, E., Kremer, V., Childs, R. & Lundqvist, A. CXCL10-induced migration of adoptively transferred human natural killer cells toward solid tumors causes regression of tumor growth in vivo. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 64, 225–235 (2015).

Somanchi, S. S., Somanchi, A., Cooper, L. J. N. & Lee, D. A. Engineering lymph node homing of ex vivo–expanded human natural killer cells via trogocytosis of the chemokine receptor CCR7. Blood 119, 5164–5172 (2012).

Carlsten, M. et al. Efficient mRNA-based genetic engineering of human NK cells with high-affinity CD16 and CCR7 augments rituximab-induced ADCC against lymphoma and targets NK cell migration toward the lymph node-associated chemokine CCL19. Front. immunol. 7, 105 (2016).

Müller, N. et al. Engineering NK cells modified with an EGFRvIII-specific chimeric antigen receptor to overexpress CXCR4 improves immunotherapy of CXCL12/SDF-1α-secreting glioblastoma. J. Immunother. 38, 197 (2015).

Kremer, V. et al. Genetic engineering of human NK cells to express CXCR2 improves migration to renal cell carcinoma. J. ImmunoTher. Cancer 5, 73 (2017).

Ponzetta, A. et al. Multiple myeloma impairs bone marrow localization of effector natural killer cells by altering the chemokine microenvironment. Cancer Res. 75, 4766–4777 (2015).

Bonanni, V., Antonangeli, F., Santoni, A. & Bernardini, G. Targeting of CXCR3 improves anti-myeloma efficacy of adoptively transferred activated natural killer cells. J. ImmunoTher. Cancer 7, 290 (2019).

Lee, J. et al. An antibody designed to improve adoptive NK-cell therapy inhibits pancreatic cancer progression in a murine model. Cancer Immunol. Res. 7, 219 (2019).

Ng, Y. Y., Tay, J. C. & Wang, S. CXCR1 expression to improve anti-cancer efficacy of intravenously injected CAR-NK cells in mice with peritoneal xenografts. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 16, 75–85 (2020).

Walle, T. et al. Radiotherapy orchestrates natural killer cell dependent antitumor immune responses through CXCL8. Sci. Adv. 8, eabh4050 (2022).

Larson, R. C. & Maus, M. V. Recent advances and discoveries in the mechanisms and functions of CAR T cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 21, 145–161 (2021).

Sterner, R. C. & Sterner, R. M. CAR-T cell therapy: current limitations and potential strategies. Blood Cancer J. 11, 69 (2021).

Gill, S. & Brudno, J. N. CAR T-cell therapy in hematologic malignancies: clinical role, toxicity, and unanswered questions. Am. Soc. Clin. Oncol. Educ. Book https://doi.org/10.1200/EDBK_320085 (2021).

Shah, N. N. & Fry, T. J. Mechanisms of resistance to CAR T cell therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 16, 372–385 (2019).

Strati, P. & Neelapu, S. S. CAR-T failure: beyond antigen loss and T cells. Blood 137, 2567–2568 (2021).

Biederstädt, A. & Rezvani, K. How I treat high-risk acute myeloid leukemia using pre-emptive adoptive cellular immunotherapy. Blood https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.2021012411 (2022).

Abdel-Hakeem, M. S. et al. Epigenetic scarring of exhausted T cells hinders memory differentiation upon eliminating chronic antigenic stimulation. Nat. Immunol. 22, 1008–1019 (2021). This article elucidates how exhausted T cell subsets fail to restore their full functional capacity upon elimination of antigenic stimulation due to persistent epigenetic scarring.

Yates, K. B. et al. Epigenetic scars of CD8+ T cell exhaustion persist after cure of chronic infection in humans. Nat. Immunol. 22, 1020–1029 (2021). This report demonstrates the fixed nature of exhausted T cell epigenetic signatures following resolution of chronic antigenic stimulation.

Biederstädt, A. et al. SUMO pathway inhibition targets an aggressive pancreatic cancer subtype. Gut 69, 1472–1482 (2020).

Kumar, S. et al. Targeting pancreatic cancer by TAK-981: a SUMOylation inhibitor that activates the immune system and blocks cancer cell cycle progression in a preclinical model. Gut https://doi.org/10.1136/gutjnl-2021-324834 (2022).

Demel, U. M. et al. Activated SUMOylation restricts MHC class I antigen presentation to confer immune evasion in cancer. J. Clin. Investig. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI152383 (2022).

Saha, K. et al. The NIH Somatic Cell Genome Editing program. Nature 592, 195–204 (2021). This report lays out the aims and scope of the NIH SCGE Consortium.

Tsai, S. Q. et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR–Cas nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 187–197 (2015).

Tsai, S. Q. et al. CIRCLE-seq: a highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR–Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat. Methods 14, 607–614 (2017).

Dobosy, J. R. et al. RNase H-dependent PCR (rhPCR): improved specificity and single nucleotide polymorphism detection using blocked cleavable primers. BMC Biotechnol. 11, 80 (2011).

Hu, J. et al. Detecting DNA double-stranded breaks in mammalian genomes by linear amplification-mediated high-throughput genome-wide translocation sequencing. Nat. Protoc. 11, 853–871 (2016).

Gillmore, J. D. et al. CRISPR–Cas9 in vivo gene editing for transthyretin amyloidosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 385, 493–502 (2021). This seminal work demonstrates the first successful clinical application of in vivo CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing.

Aghajanian, H. et al. Targeting cardiac fibrosis with engineered T cells. Nature 573, 430–433 (2019).

Rurik, J. G. et al. CAR T cells produced in vivo to treat cardiac injury. Science 375, 91–96 (2022). This study demonstrates the first successful in vivo engineering of CAR T cells using a CD5-directed lipid nanoparticle containing CAR-encoding mRNA.

Bender, R. R., Muth, A., Schneider, I. C., Maisner, A. & Buchholz, C. J. Developing an engineered nipah virus glycoprotein based lentiviral vector system retargeted to cell surface receptors of choice. Mol. Ther. 23, S2 (2015).

Micklethwaite, K. P. et al. Investigation of product-derived lymphoma following infusion of piggyBac-modified CD19 chimeric antigen receptor T cells. Blood 138, 1391–1405 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02742727 (2016).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT00995137 (2009).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT01974479 (2013).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02892695 (2016).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03056339 (2017).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03824951 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03690310 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05020678 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04245722 (2020).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04639739 (2020).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04887012 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04796675 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04796688 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05379647 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05336409 (2022).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04023071 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03692767 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03824964 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02944162 (2016).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05008575 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05215015 (2020).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05092451 (2022).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03559764 (2018).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03940833 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05008536 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05182073 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04614636 (2020).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04623944 (2020).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03415100 (2018).

Xiao, L. et al. Adoptive transfer of NKG2D CAR mRNA-engineered natural killer cells in colorectal cancer patients. Mol. Ther. 27, 1114–1125 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05213195 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05247957 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT02839954 (2016).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03383978 (2017).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03692663 (2018).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03692637 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04630769 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03940820 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03931720 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT03941457 (2019).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04551885 (2020).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04847466 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT05194709 (2021).

US National Library of Medicine. ClinicalTrials.gov https://ClinicalTrials.gov/show/NCT04324996 (2020).

Wu, L. et al. lenalidomide enhances natural killer cell and monocyte-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity of rituximab-treated CD20+ tumor cells. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 4650–4657 (2008).

Tai, Y. T. et al. Immunomodulatory drug lenalidomide (CC-5013, IMiD3) augments anti-CD40 SGN-40-induced cytotoxicity in human multiple myeloma: clinical implications. Cancer Res. 65, 11712–11720 (2005).

Nahas, M. R. et al. Hypomethylating agent alters the immune microenvironment in acute myeloid leukaemia (AML) and enhances the immunogenicity of a dendritic cell/AML vaccine. Br. J. Haematol. 185, 679–690 (2019).

Hicks, K. C. et al. Epigenetic priming of both tumor and NK cells augments antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity elicited by the anti-PD-L1 antibody avelumab against multiple carcinoma cell types. OncoImmunology 7, e1466018 (2018).

Leung, E. Y. L. et al. NK cells augment oncolytic adenovirus cytotoxicity in ovarian cancer. Mol. Ther. Oncolytics 16, 289–301 (2020).

Marotel, M., Hasim, M. S., Hagerman, A. & Ardolino, M. The two-faces of NK cells in oncolytic virotherapy. Cytokine Growth Factor. Rev. 56, 59–68 (2020).

Cichocki, F. et al. GSK3 inhibition drives maturation of NK cells and enhances their antitumor activity. Cancer Res. 77, 5664–5675 (2017).

Parameswaran, R. et al. Repression of GSK3 restores NK cell cytotoxicity in AML patients. Nat. Commun. 7, 11154 (2016).

van Hall, T. et al. Monalizumab: inhibiting the novel immune checkpoint NKG2A. J. Immunother. Cancer 7, 263 (2019).

Yalniz, F. F. et al. A pilot trial of Lirilumab with or without azacitidine for patients with myelodysplastic syndrome. Clin. Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 18, 658–663.e2 (2018).

Bachier, C. et al. A phase 1 study of NKX101, an allogeneic CAR natural killer (NK) cell therapy, in subjects with relapsed/refractory (R/R) acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or higher-risk myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS). Blood 136, 42–43 (2020).

Pinz, K. G. et al. Targeting T-cell malignancies using anti-CD4 CAR NK-92 cells. Oncotarget 8, 112783–112796 (2017).

Romanski, A. et al. CD19-CAR engineered NK-92 cells are sufficient to overcome NK cell resistance in B-cell malignancies. J. Cell Mol. Med. 20, 1287–1294 (2016).

You, F. et al. A novel CD7 chimeric antigen receptor-modified NK-92MI cell line targeting T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Am. J. Cancer Res. 9, 64–78 (2019).

Xu, Y. et al. 2B4 costimulatory domain enhancing cytotoxic ability of anti-CD5 chimeric antigen receptor engineered natural killer cells against T cell malignancies. J. Hematol. Oncol. 12, 49 (2019).

Martín, E. M. et al. Exploring NKG2D and BCMA-CAR NK-92 for adoptive cellular therapy to multiple myeloma. Clin. Lymphoma, Myeloma Leuk. 19, e24–e25 (2019).

Jiang, H. et al. Transfection of chimeric anti-CD138 gene enhances natural killer cell activation and killing of multiple myeloma cells. Mol. Oncol. 8, 297–310 (2014).

Han, J. et al. CAR-engineered NK cells targeting wild-type EGFR and EGFRvIII enhance killing of glioblastoma and patient-derived glioblastoma stem cells. Sci. Rep. 5, 11483 (2015).

Chu, J. et al. CS1-specific chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-engineered natural killer cells enhance in vitro and in vivo antitumor activity against human multiple myeloma. Leukemia 28, 917–927 (2014).

Chen, K. H. et al. Preclinical targeting of aggressive T-cell malignancies using anti-CD5 chimeric antigen receptor. Leukemia 31, 2151–2160 (2017).

Chen, K. H. et al. Novel anti-CD3 chimeric antigen receptor targeting of aggressive T cell malignancies. Oncotarget 7, 56219–56232 (2016).

Vallera, D. A. et al. NK-cell-mediated targeting of various solid tumors using a B7-H3 tri-specific killer engager in vitro and in vivo. Cancers https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers12092659 (2020).

Cooper, L. J. et al. T-cell clones can be rendered specific for CD19: toward the selective augmentation of the graft-versus-B-lineage leukemia effect. Blood 101, 1637–1644 (2003).

Imai, C. et al. Chimeric receptors with 4-1BB signaling capacity provoke potent cytotoxicity against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 18, 676–684 (2004).

Maher, J., Brentjens, R. J., Gunset, G., Rivière, I. & Sadelain, M. Human T-lymphocyte cytotoxicity and proliferation directed by a single chimeric TCRζ/CD28 receptor. Nat. Biotechnol. 20, 70–75 (2002).

Schubert, M.-L. et al. Third-generation CAR T cells targeting CD19 are associated with an excellent safety profile and might improve persistence of CAR T cells in treated patients. Blood 134, 51–51 (2019).

Bjordahl, R. et al. Abstract 1539: development of off-the-shelf B7H3 chimeric antigen receptor NK cell therapeutic with broad applicability across many solid tumors. Cancer Res. 81, 1539 (2021).

Basar, R. et al. Generation of glucocorticoid-resistant SARS-CoV-2 T cells for adoptive cell therapy. Cell Rep. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109432 (2021).

Shalem, O. et al. Genome-scale CRISPR–Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science 343, 84–87 (2014).

Wang, T., Wei, J. J., Sabatini, D. M. & Lander, E. S. Genetic screens in human cells using the CRISPR–Cas9 system. Science 343, 80–84 (2014).

Manguso, R. T. et al. In vivo CRISPR screening identifies Ptpn2 as a cancer immunotherapy target. Nature 547, 413–418 (2017).

Patel, S. J. et al. Identification of essential genes for cancer immunotherapy. Nature 548, 537–542 (2017).

Pan, D. et al. A major chromatin regulator determines resistance of tumor cells to T cell-mediated killing. Science 359, 770–775 (2018).

Shang, W. et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screen identifies FAM49B as a key regulator of actin dynamics and T cell activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 115, E4051 (2018).

Ishizuka, J. J. et al. Loss of ADAR1 in tumours overcomes resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Nature 565, 43–48 (2019).

Lawson, K. A. et al. Functional genomic landscape of cancer-intrinsic evasion of killing by T cells. Nature 586, 120–126 (2020).

Sheffer, M. et al. Genome-scale screens identify factors regulating tumor cell responses to natural killer cells. Nat. Genet. 53, 1196–1206 (2021). This report uses an orthogonal approach combining genome-wide CRISPR screening with multiplexed cancer cell line screening to decipher cancer type-specific vulnerabilities towards NK cells.

Ting, P. Y. et al. Guide Swap enables genome-scale pooled CRISPR–Cas9 screening in human primary cells. Nat. Methods 15, 941–946 (2018).

Shifrut, E. et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screens in primary human T cells reveal key regulators of immune function. Cell 175, 1958–1971.e15 (2018).

Wang, D. et al. CRISPR screening of CAR T cells and cancer stem cells reveals critical dependencies for cell-based therapies. Cancer Discov. 11, 1192–1211 (2021).

Roth, T. L. et al. Pooled knockin targeting for genome engineering of cellular immunotherapies. Cell 181, 728–744.e21 (2020).

Legut, M. et al. A genome-scale screen for synthetic drivers of T cell proliferation. Nature 603, 728–735 (2022).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. S. Moyes for providing editing support during the preparation of this manuscript. A.B. received support from the German Research Foundation as Walter Benjamin Postdoctoral Fellow (464778766). This work was supported, in part, by generous philanthropic contributions to The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Moon Shots Program, The Sally Cooper Murray endowment, generous support of Ann and Clarence Cazalot, and Lyda Hill Philanthropies; and by grants from CPRIT (RP160693), a Stand Up To Cancer Dream Team Research Grant (Grant number: SU2C-AACR-DT-29-19), grants from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1 R01 CA211044-01, 5 P01CA148600-03, and P50CA100632-16), the Specialized Program of Research Excellence (SPORE) in Brain Cancer Grant (P50CA127001) and a grant to MD Anderson Cancer Center from the NIH (CA016672). The SU2C research grant is administered by the American Association for Cancer Research, the scientific partner of SU2C.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

K.R. and The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have an institutional financial conflict of interest with Takeda Pharmaceutical and Affimed GmbH. K.R. participates on the Scientific Advisory Board for GemoAb, AvengeBio, Virogin Biotech, GSK, Bayer, Navan Technologies and Caribou Biosciences. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Cancer thanks E. Vivier, who co-reviewed with P. Andre, and A. Cerwenka and S. Gill for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Glossary

- Autologous chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy

-

A patient-specific cellular therapy in which the patient’s own T cells are genetically modified to express a chimeric antigen receptor.

- Lymphopenic

-

A lower than normal number of lymphocytes in the blood.

- Allogeneic setting

-

The therapy setting in which adoptive cell therapies are generated from material obtained from a different individual of the same species.

- Graft-versus-host disease

-

(GvHD). A potentially fatal condition that results from the response of allogeneic T cells against the host tissues of recipients who are immunosuppressed, which can occur after adoptive cell therapy or allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

- Killer cell immunoglobulin-like receptors

-

(KIRs). A family of polymorphic activating and inhibitory transmembrane proteins that regulate natural killer cell development and function through interactions with major histocompatibility complex class I molecules.

- Induced pluripotent stem cells

-

(iPSCs). Cells that result from the reprogramming of adult somatic cells into an embryonic-like pluripotent stem cell state, capable of self-renewal and differentiation into tissues originated from the three germ layers (endoderm, mesoderm and ectoderm).

- Apheresis

-

The process that allows for collection of specific components from blood, such as white blood cells, by separating the cellular and soluble fractions, retaining what is of interest and returning the remainder to circulation.

- Chimeric antigen receptors

-

(CARs). Genetically engineered cell surface receptors designed to recognize specific proteins on tumour cells.

- Tonic signalling

-

The constitutive signalling mediated by a chimeric antigen receptor in a ligand-independent manner.

- Logic gated

-

A term derived from electronics that refers to implementation of a Boolean strategy to execute a logical function on one or more input signals to generate a single output signal.

- Licensing

-

A process of education in maturing natural killer (NK) cells that is driven by the interaction of inhibitory receptors and self-major histocompatibility complex class I molecules, which potentiates NK cell responses to activating signals.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Laskowski, T.J., Biederstädt, A. & Rezvani, K. Natural killer cells in antitumour adoptive cell immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 22, 557–575 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-022-00491-0

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41568-022-00491-0

This article is cited by

-

Advances in cancer immunotherapy: historical perspectives, current developments, and future directions

Molecular Cancer (2025)

-

Interleukin-21 engineering enhances CD19-specific CAR-NK cell activity against B-cell lymphoma via enriched metabolic pathways

Experimental Hematology & Oncology (2025)

-

Directly reprogrammed NK cells driven by BCL11B depletion enhance targeted immunotherapy against pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

Journal of Hematology & Oncology (2025)

-

5-FU@HFn combined with decitabine induces pyroptosis and enhances antitumor immunotherapy for chronic myeloid leukemia

Journal of Nanobiotechnology (2025)

-

IRG1/itaconate enhances efferocytosis by activating Nrf2-TIM4 signaling pathway to alleviate con A induced autoimmune liver injury

Cell Communication and Signaling (2025)