Abstract

Apolipoprotein B (apoB) is the main structural protein of LDLs, triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and lipoprotein(a), and is crucial for their formation, metabolism and atherogenic properties. In this Review, we present insights into the role of apoB-containing lipoproteins in atherogenesis, with an emphasis on the mechanisms leading to plaque initiation and growth. LDL, the most abundant cholesterol-rich lipoprotein in plasma, is causally linked to atherosclerosis. LDL enters the artery wall by transcytosis and, in vulnerable regions, is retained in the subendothelial space by binding to proteoglycans via specific sites on apoB. A maladaptive response ensues. This response involves modification of LDL particles, which promotes LDL retention and the release of bioactive lipid products that trigger inflammatory responses in vascular cells, as well as adaptive immune responses. Resident and recruited macrophages take up modified LDL, leading to foam cell formation and ultimately cell death due to inadequate cellular lipid handling. Accumulation of dead cells and cholesterol crystallization are hallmarks of the necrotic core of atherosclerotic plaques. Other apoB-containing lipoproteins, although less abundant, have substantially greater atherogenicity per particle than LDL. These lipoproteins probably contribute to atherogenesis in a similar way to LDL but might also induce additional pathogenic mechanisms. Several targets for intervention to reduce the rate of atherosclerotic lesion initiation and progression have now been identified, including lowering plasma lipoprotein levels and modulating the maladaptive responses in the artery wall.

Key points

-

LDL is the main carrier of cholesterol in the blood and of circulating cholesterol into the artery wall.

-

LDL is a proven causative factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and reducing the plasma levels of LDL substantially reduces cardiovascular risk.

-

Subendothelial retention of LDL and other apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins is the primary trigger for the development of atherosclerosis.

-

Retained LDL becomes modified in the artery wall, and the focal accumulation of modified lipoproteins triggers the recruitment of monocytes and macrophages.

-

Damage-associated molecular patterns, formed when retained LDL is modified, induce a maladaptive immune response.

-

Different species of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins are not equally atherogenic; triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants and lipoprotein(a) are markedly more atherogenic than LDL.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$189.00 per year

only $15.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Tsao, C. W. et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2022 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 145, e153–e639 (2022).

Ference, B. A. et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. 1. Evidence from genetic, epidemiologic, and clinical studies. A consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur. Heart J. 38, 2459–2472 (2017).

Boren, J. et al. Low-density lipoproteins cause atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: pathophysiological, genetic, and therapeutic insights: a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. Eur. Heart J. 41, 2313–2330 (2020).

Skalen, K. et al. Subendothelial retention of atherogenic lipoproteins in early atherosclerosis. Nature 417, 750–754 (2002).

Tabas, I., Williams, K. J. & Boren, J. Subendothelial lipoprotein retention as the initiating process in atherosclerosis: update and therapeutic implications. Circulation 116, 1832–1844 (2007).

Robinson, J. G. et al. Eradicating the burden of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease by lowering apolipoprotein B lipoproteins earlier in life. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 7, e009778 (2018).

Williams, K. J. & Tabas, I. The response-to-retention hypothesis of early atherogenesis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 15, 551–561 (1995).

Camejo, G., Lopez, A., Vegas, H. & Paoli, H. The participation of aortic proteins in the formation of complexes between low density lipoproteins and intima-media extracts. Atherosclerosis 21, 77–91 (1975).

Segrest, J. P., Jones, M. K., De Loof, H. & Dashti, N. Structure of apolipoprotein B-100 in low density lipoproteins. J. Lipid Res. 42, 1346–1367 (2001).

Segrest, J. P. et al. Apolipoprotein B-100: conservation of lipid-associating amphipathic secondary structural motifs in nine species of vertebrates. J. Lipid Res. 39, 85–102 (1998).

Boren, J., Taskinen, M. R., Bjornson, E. & Packard, C. J. Metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in health and dyslipidaemia. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 19, 577–592 (2022).

Frank, P. G. & Lisanti, M. P. Caveolin-1 and caveolae in atherosclerosis: differential roles in fatty streak formation and neointimal hyperplasia. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 15, 523–529 (2004).

Fernandez-Hernando, C. et al. Genetic evidence supporting a critical role of endothelial caveolin-1 during the progression of atherosclerosis. Cell Metab. 10, 48–54 (2009).

Frank, P. G., Pavlides, S. & Lisanti, M. P. Caveolae and transcytosis in endothelial cells: role in atherosclerosis. Cell Tissue Res. 335, 41–47 (2009).

Armstrong, S. M. et al. Novel assay for detection of LDL transcytosis across coronary endothelium reveals an unexpected role for SR-B1 [abstract]. Circulation 130 (Suppl. 2), A11607 (2014).

Kraehling, J. R. et al. Genome-wide RNAi screen ALK1 mediates LDL uptake and transcytosis in endothelial cells. Nat. Commun. 7, 13516 (2016).

Minick, C. R., Stemerman, M. G. & Insull, W. Jr Effect of regenerated endothelium on lipid accumulation in the arterial wall. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 74, 1724–1728 (1977).

Minick, C. R., Stemerman, M. B. & Insull, W. Jr Role of endothelium and hypercholesterolemia in intimal thickening and lipid accumulation. Am. J. Pathol. 95, 131–158 (1979).

Armstrong, S. M. et al. A novel assay uncovers an unexpected role for SR-BI in LDL transcytosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 108, 268–277 (2015).

Huang, L. et al. SR-B1 drives endothelial cell LDL transcytosis via DOCK4 to promote atherosclerosis. Nature 569, 565–569 (2019).

Sessa, W. C. Estrogen reduces LDL (low-density lipoprotein) transcytosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 38, 2276–2277 (2018).

Ghaffari, S., Naderi Nabi, F., Sugiyama, M. G. & Lee, W. L. Estrogen inhibits LDL (low-density lipoprotein) transcytosis by human coronary artery endothelial cells via GPER (G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor) and SR-BI (scavenger receptor class B type 1). Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 38, 2283–2294 (2018).

Mathur, P., Ostadal, B., Romeo, F. & Mehta, J. L. Gender-related differences in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Drugs Ther. 29, 319–327 (2015).

Bian, F., Yang, X. Y., Xu, G., Zheng, T. & Jin, S. CRP-induced NLRP3 inflammasome activation increases LDL transcytosis across endothelial cells. Front. Pharmacol. 10, 40 (2019).

Jia, X. et al. VCAM-1-binding peptide targeted cationic liposomes containing NLRP3 siRNA to modulate LDL transcytosis as a novel therapy for experimental atherosclerosis. Metabolism 135, 155274 (2022).

Arsenault, B. J., Carpentier, A. C., Poirier, P. & Despres, J. P. Adiposity, type 2 diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk: use and abuse of the body mass index. Atherosclerosis 394, 117546 (2024).

Bartels, E. D., Christoffersen, C., Lindholm, M. W. & Nielsen, L. B. Altered metabolism of LDL in the arterial wall precedes atherosclerosis regression. Circ. Res. 117, 933–942 (2015).

Mundi, S. et al. Endothelial permeability, LDL deposition, and cardiovascular risk factors – a review. Cardiovasc. Res. 114, 35–52 (2018).

van den Berg, B. M., Spaan, J. A., Rolf, T. M. & Vink, H. Atherogenic region and diet diminish glycocalyx dimension and increase intima-to-media ratios at murine carotid artery bifurcation. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 290, H915–H920 (2006).

Lewis, J. C., Taylor, R. G., Jones, N. D., St Clair, R. W. & Cornhill, J. F. Endothelial surface characteristics in pigeon coronary artery atherosclerosis. I. Cellular alterations during the initial stages of dietary cholesterol challenge. Lab. Invest. 46, 123–138 (1982).

Cancel, L. M., Ebong, E. E., Mensah, S., Hirschberg, C. & Tarbell, J. M. Endothelial glycocalyx, apoptosis and inflammation in an atherosclerotic mouse model. Atherosclerosis 252, 136–146 (2016).

Banerjee, S., Mwangi, J. G., Stanley, T. K., Mitra, R. & Ebong, E. E. Regeneration and assessment of the endothelial glycocalyx to address cardiovascular disease. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 60, 17328–17347 (2021).

Faber, M. The human aorta; sulfate-containing polyuronides and the deposition of cholesterol. Arch. Pathol. 48, 342–350 (1949).

Camejo, G. et al. Differences in the structure of plasma low-density lipoproteins and their relationship to the extent of interaction with arterial wall-components. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 275, 153–168 (1976).

Camejo, G. The interaction of lipids and lipoproteins with the intercellular matrix of arterial tissue: its possible role in atherogenesis. Adv. Lipid Res. 19, 1–53 (1982).

Camejo, G., Olofsson, S. O., Lopez, F., Carlsson, P. & Bondjers, G. Identification of Apo B-100 segments mediating the interaction of low density lipoproteins with arterial proteoglycans. Arteriosclerosis 8, 368–377 (1988).

Hirose, N., Blankenship, D. T., Krivanek, M. A., Jackson, R. L. & Cardin, A. D. Isolation and characterization of four heparin-binding cyanogen bromide peptides of human plasma apolipoprotein B. Biochemistry 26, 5505–5512 (1987).

Weisgraber, K. H. & Rall, S. C. Jr Human apolipoprotein B-100 heparin-binding sites. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 11097–11103 (1987).

Boren, J. et al. Identification of the principal proteoglycan-binding site in LDL. A single-point mutation in apo-B100 severely affects proteoglycan interaction without affecting LDL receptor binding. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 2658–2664 (1998).

Boren, J. et al. Identification of the low density lipoprotein receptor-binding site in apolipoprotein B100 and the modulation of its binding activity by the carboxyl terminus in familial defective apo-B100. J. Clin. Invest. 101, 1084–1093 (1998).

Chan, L. Apolipoprotein B, the major protein component of triglyceride-rich and low density lipoproteins. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 25621–25624 (1992).

Flood, C. et al. Identification of the proteoglycan binding site in apolipoprotein B48. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 32228–32233 (2002).

Flood, C. et al. Molecular mechanism for changes in proteoglycan binding on compositional changes of the core and the surface of low-density lipoprotein-containing human apolipoprotein B100. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 24, 564–570 (2004).

Camejo, G., Olsson, U., Hurt-Camejo, E., Baharamian, N. & Bondjers, G. The extracellular matrix on atherogenesis and diabetes-associated vascular disease. Atheroscler. Suppl. 3, 3–9 (2002).

Sartipy, P., Camejo, G., Svensson, L. & Hurt-Camejo, E. Phospholipase A2 modification of low density lipoproteins forms small high density particles with increased affinity for proteoglycans and glycosaminoglycans. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25913–25920 (1999).

Kugiyama, K. et al. Circulating levels of secretory type II phospholipase A2 predict coronary events in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation 100, 1280–1284 (1999).

The Lp-PLA2 Studies Collaboration et al.Lipoprotein-associated phospholipase A2 and risk of coronary disease, stroke, and mortality: collaborative analysis of 32 prospective studies. Lancet 375, 1536–1544 (2010).

Griffin, B. A. et al. Role of plasma triglyceride in the regulation of plasma low density lipoprotein (LDL) subfractions: relative contribution of small, dense LDL to coronary heart disease risk. Atherosclerosis 106, 241–253 (1994).

Austin, M. A., King, M. C., Vranizan, K. M. & Krauss, R. M. Atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype. A proposed genetic marker for coronary heart disease risk. Circulation 82, 495–506 (1990).

Nicholls, S. J. et al. Varespladib and cardiovascular events in patients with an acute coronary syndrome: the VISTA-16 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 311, 252–262 (2014).

Gregson, J. M. et al. Genetic invalidation of Lp-PLA2 as a therapeutic target: large-scale study of five functional Lp-PLA2-lowering alleles. Eur. J. Prev. Cardiol. 24, 492–504 (2017).

Schwenke, D. C. & Carew, T. E. Initiation of atherosclerotic lesions in cholesterol-fed rabbits. II. Selective retention of LDL vs. selective increases in LDL permeability in susceptible sites of arteries. Arteriosclerosis 9, 908–918 (1989).

Tran-Lundmark, K. et al. Heparan sulfate in perlecan promotes mouse atherosclerosis: roles in lipid permeability, lipid retention, and smooth muscle cell proliferation. Circ. Res. 103, 43–52 (2008).

Mahley, R. W. & Huang, Y. Atherogenic remnant lipoproteins: role for proteoglycans in trapping, transferring, and internalizing. J. Clin. Invest. 117, 94–98 (2007).

Hiukka, A. et al. ApoCIII-enriched LDL in type 2 diabetes displays altered lipid composition, increased susceptibility for sphingomyelinase, and increased binding to biglycan. Diabetes 58, 2018–2026 (2009).

Olin-Lewis, K. et al. ApoC-III content of apoB-containing lipoproteins is associated with binding to the vascular proteoglycan biglycan. J. Lipid Res. 43, 1969–1977 (2002).

Jayaraman, S. et al. Effects of triacylglycerol on the structural remodeling of human plasma very low- and low-density lipoproteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 1864, 1061–1071 (2019).

Willner, E. L. et al. Deficiency of acyl CoA:cholesterol acyltransferase 2 prevents atherosclerosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1262–1267 (2003).

Aviram, M., Lund-Katz, S., Phillips, M. C. & Chait, A. The influence of the triglyceride content of low density lipoprotein on the interaction of apolipoprotein B-100 with cells. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 16842–16848 (1988).

Hagensen, M. K. et al. Increased retention of LDL from type 1 diabetic patients in atherosclerosis-prone areas of the murine arterial wall. Atherosclerosis 286, 156–162 (2019).

O’Brien, K. D. et al. Comparison of apolipoprotein and proteoglycan deposits in human coronary atherosclerotic plaques: colocalization of biglycan with apolipoproteins. Circulation 98, 519–527 (1998).

Nakashima, Y., Fujii, H., Sumiyoshi, S., Wight, T. N. & Sueishi, K. Early human atherosclerosis: accumulation of lipid and proteoglycans in intimal thickenings followed by macrophage infiltration. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 1159–1165 (2007).

She, Z. G. et al. NG2 proteoglycan ablation reduces foam cell formation and atherogenesis via decreased low-density lipoprotein retention by synthetic smooth muscle cells. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 36, 49–59 (2016).

Tsiantoulas, D. et al. APRIL limits atherosclerosis by binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Nature 597, 92–96 (2021).

Brito, V. et al. Atheroregressive potential of the treatment with a chimeric monoclonal antibody against sulfated glycosaminoglycans on pre-existing lesions in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Front. Pharmacol. 8, 782 (2017).

Nakashima, Y., Chen, Y. X., Kinukawa, N. & Sueishi, K. Distributions of diffuse intimal thickening in human arteries: preferential expression in atherosclerosis-prone arteries from an early age. Virchows Arch. 441, 279–288 (2002).

Stary, H. C. et al. A definition of the intima of human arteries and of its atherosclerosis-prone regions. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Arterioscler. Thromb. 12, 120–134 (1992).

Kaprio, J., Norio, R., Pesonen, E. & Sarna, S. Intimal thickening of the coronary arteries in infants in relation to family history of coronary artery disease. Circulation 87, 1960–1968 (1993).

Allahverdian, S., Ortega, C. & Francis, G. A. Smooth muscle cell-proteoglycan-lipoprotein interactions as drivers of atherosclerosis. Handb. Exp. Pharmacol. 270, 335–358 (2022).

Kolodgie, F. D., Burke, A. P., Nakazawa, G. & Virmani, R. Is pathologic intimal thickening the key to understanding early plaque progression in human atherosclerotic disease? Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 27, 986–989 (2007).

Kijani, S., Vazquez, A. M., Levin, M., Boren, J. & Fogelstrand, P. Intimal hyperplasia induced by vascular intervention causes lipoprotein retention and accelerated atherosclerosis. Physiol. Rep. 5, e13334 (2017).

Kalan, J. M. & Roberts, W. C. Morphologic findings in saphenous veins used as coronary arterial bypass conduits for longer than 1 year: necropsy analysis of 53 patients, 123 saphenous veins, and 1865 five-millimeter segments of veins. Am. Heart J. 119, 1164–1184 (1990).

Williams, K. J. Arterial zones that take a pause in early plaque development. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 43, 650–653 (2023).

Lewis, E. A. et al. Capacity for LDL (low-density lipoprotein) retention predicts the course of atherogenesis in the murine aortic arch. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 43, 637–649 (2023).

Oorni, K. et al. Acidification of the intimal fluid: the perfect storm for atherogenesis. J. Lipid Res. 56, 203–214 (2015).

Tomas, L. et al. Altered metabolism distinguishes high-risk from stable carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Eur. Heart J. 39, 2301–2310 (2018).

Glise, L. et al. pH-dependent protonation of histidine residues is critical for electrostatic binding of low-density lipoproteins to human coronary arteries. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 42, 1037–1047 (2022).

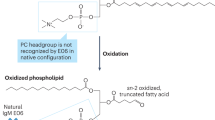

Lorey, M. B., Oorni, K. & Kovanen, P. T. Modified lipoproteins induce arterial wall inflammation during atherogenesis. Front. Cardiovasc. Med. 9, 841545 (2022).

Binder, C. J., Papac-Milicevic, N. & Witztum, J. L. Innate sensing of oxidation-specific epitopes in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 16, 485–497 (2016).

Esterbauer, H., Schaur, R. J. & Zollner, H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 11, 81–128 (1991).

Bochkov, V. N. et al. Generation and biological activities of oxidized phospholipids. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 12, 1009–1059 (2010).

Tsimikas, S. & Witztum, J. L. Oxidized phospholipids in cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21, 170–191 (2024).

Byun, Y. S. et al. Relationship of oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B-100 to cardiovascular outcomes in patients treated with intensive versus moderate atorvastatin therapy: the TNT trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 65, 1286–1295 (2015).

Gilliland, T. C. et al. Lipoprotein(a), oxidized phospholipids, and coronary artery disease severity and outcomes. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 81, 1780–1792 (2023).

Tsimikas, S. et al. Relationship of oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein B-100 particles to race/ethnicity, apolipoprotein(a) isoform size, and cardiovascular risk factors: results from the Dallas Heart Study. Circulation 119, 1711–1719 (2009).

Camejo, G., Fager, G., Rosengren, B., Hurt-Camejo, E. & Bondjers, G. Binding of low density lipoproteins by proteoglycans synthesized by proliferating and quiescent human arterial smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 14131–14137 (1993).

Chang, M. Y., Potter-Perigo, S., Tsoi, C., Chait, A. & Wight, T. N. Oxidized low density lipoproteins regulate synthesis of monkey aortic smooth muscle cell proteoglycans that have enhanced native low density lipoprotein binding properties. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 4766–4773 (2000).

Gustafsson, M. et al. Retention of low-density lipoprotein in atherosclerotic lesions of the mouse: evidence for a role of lipoprotein lipase. Circ. Res. 101, 777–783 (2007).

Pentikainen, M. O., Oksjoki, R., Oorni, K. & Kovanen, P. T. Lipoprotein lipase in the arterial wall: linking LDL to the arterial extracellular matrix and much more. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 22, 211–217 (2002).

Pentikainen, M. O., Oorni, K. & Kovanen, P. T. Lipoprotein lipase (LPL) strongly links native and oxidized low density lipoprotein particles to decorin-coated collagen. Roles for both dimeric and monomeric forms of LPL. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 5694–5701 (2000).

Babaev, V. R. et al. Macrophage lipoprotein lipase promotes foam cell formation and atherosclerosis in vivo. J. Clin. Invest. 103, 1697–1705 (1999).

Wilson, K., Fry, G. L., Chappell, D. A., Sigmund, C. D. & Medh, J. D. Macrophage-specific expression of human lipoprotein lipase accelerates atherosclerosis in transgenic apolipoprotein E knockout mice but not in C57BL/6 mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 21, 1809–1815 (2001).

Tabas, I. et al. Lipoprotein lipase and sphingomyelinase synergistically enhance the association of atherogenic lipoproteins with smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix. A possible mechanism for low density lipoprotein and lipoprotein(a) retention and macrophage foam cell formation. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 20419–20432 (1993).

Devlin, C. M. et al. Acid sphingomyelinase promotes lipoprotein retention within early atheromata and accelerates lesion progression. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 28, 1723–1730 (2008).

Oorni, K., Hakala, J. K., Annila, A., Ala-Korpela, M. & Kovanen, P. T. Sphingomyelinase induces aggregation and fusion, but phospholipase A2 only aggregation, of low density lipoprotein (LDL) particles. Two distinct mechanisms leading to increased binding strength of LDL to human aortic proteoglycans. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 29127–29134 (1998).

Wong, M. L. et al. Acute systemic inflammation up-regulates secretory sphingomyelinase in vivo: a possible link between inflammatory cytokines and atherogenesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 8681–8686 (2000).

Marathe, S., Kuriakose, G., Williams, K. J. & Tabas, I. Sphingomyelinase, an enzyme implicated in atherogenesis, is present in atherosclerotic lesions and binds to specific components of the subendothelial extracellular matrix. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 2648–2658 (1999).

Marathe, S., Choi, Y., Leventhal, A. R. & Tabas, I. Sphingomyelinase converts lipoproteins from apolipoprotein E knockout mice into potent inducers of macrophage foam cell formation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 20, 2607–2613 (2000).

Ruuth, M. et al. Susceptibility of low-density lipoprotein particles to aggregate depends on particle lipidome, is modifiable, and associates with future cardiovascular deaths. Eur. Heart J. 39, 2562–2573 (2018).

Sanda, G. M. et al. Aggregated LDL turn human macrophages into foam cells and induce mitochondrial dysfunction without triggering oxidative or endoplasmic reticulum stress. PLoS ONE 16, e0245797 (2021).

Steinfeld, N., Ma, C. J. & Maxfield, F. R. Signaling pathways regulating the extracellular digestion of lipoprotein aggregates by macrophages. Mol. Biol. Cell 35, ar5 (2024).

Cohen, J. C., Boerwinkle, E., Mosley, T. H. Jr. & Hobbs, H. H. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 354, 1264–1272 (2006).

Nissen, S. E. et al. Effect of torcetrapib on the progression of coronary atherosclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 1304–1316 (2007).

Sneck, M. et al. Conformational changes of apoB-100 in SMase-modified LDL mediate formation of large aggregates at acidic pH. J. Lipid Res. 53, 1832–1839 (2012).

Zernecke, A. et al. Meta-analysis of leukocyte diversity in atherosclerotic mouse aortas. Circ. Res. 127, 402–426 (2020).

Depuydt, M. A. C. et al. Microanatomy of the human atherosclerotic plaque by single-cell transcriptomics. Circ. Res. 127, 1437–1455 (2020).

de Winther, M. P. J. et al. Translational opportunities of single-cell biology in atherosclerosis. Eur. Heart J. 44, 1216–1230 (2023).

Williams, J. W. et al. Limited proliferation capacity of aortic intima resident macrophages requires monocyte recruitment for atherosclerotic plaque progression. Nat. Immunol. 21, 1194–1204 (2020).

Takaoka, M. et al. Early intermittent hyperlipidaemia alters tissue macrophages to fuel atherosclerosis. Nature 634, 457–465 (2024).

Moore, K. J. et al. Macrophage trafficking, inflammatory resolution, and genomics in atherosclerosis: JACC Macrophage in CVD Series (part 2). J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 72, 2181–2197 (2018).

Spann, N. J. et al. Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell 151, 138–152 (2012).

Cochain, C. et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals the transcriptional landscape and heterogeneity of aortic macrophages in murine atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 122, 1661–1674 (2018).

Piollet, M. et al. TREM2 protects from atherosclerosis by limiting necrotic core formation. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 3, 269–282 (2024).

Dib, L. et al. Lipid-associated macrophages transition to an inflammatory state in human atherosclerosis increasing the risk of cerebrovascular complications. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2, 656–672 (2023).

Zernecke, A. et al. Integrated single-cell analysis-based classification of vascular mononuclear phagocytes in mouse and human atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 119, 1676–1689 (2023).

Adkar, S. S. & Leeper, N. J. Efferocytosis in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21, 762–779 (2024).

Doran, A. C., Yurdagul, A. Jr. & Tabas, I. Efferocytosis in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 20, 254–267 (2020).

Seimon, T. A. et al. Atherogenic lipids and lipoproteins trigger CD36-TLR2-dependent apoptosis in macrophages undergoing endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 12, 467–482 (2010).

De Meyer, G. R. Y., Zurek, M., Puylaert, P. & Martinet, W. Programmed death of macrophages in atherosclerosis: mechanisms and therapeutic targets. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21, 312–325 (2024).

Lehti, S. et al. Extracellular lipids accumulate in human carotid arteries as distinct three-dimensional structures and have proinflammatory properties. Am. J. Pathol. 188, 525–538 (2018).

Oorni, K. & Kovanen, P. T. Enhanced extracellular lipid accumulation in acidic environments. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 17, 534–540 (2006).

Kiss, M. G. & Binder, C. J. The multifaceted impact of complement on atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 351, 29–40 (2022).

Duewell, P. et al. NLRP3 inflammasomes are required for atherogenesis and activated by cholesterol crystals. Nature 464, 1357–1361 (2010).

Rajamaki, K. et al. Cholesterol crystals activate the NLRP3 inflammasome in human macrophages: a novel link between cholesterol metabolism and inflammation. PLoS ONE 5, e11765 (2010).

Grebe, A., Hoss, F. & Latz, E. NLRP3 inflammasome and the IL-1 pathway in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 122, 1722–1740 (2018).

Ridker, P. M. et al. Antiinflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 1119–1131 (2017).

Fiolet, A. T. L. et al. Efficacy and safety of low-dose colchicine in patients with coronary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Eur. Heart J. 42, 2765–2775 (2021).

Ridker, P. M. From RESCUE to ZEUS: will interleukin-6 inhibition with ziltivekimab prove effective for cardiovascular event reduction? Cardiovasc. Res. 117, e138–e140 (2021).

Stewart, C. R. et al. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat. Immunol. 11, 155–161 (2010).

Sheedy, F. J. et al. CD36 coordinates NLRP3 inflammasome activation by facilitating intracellular nucleation of soluble ligands into particulate ligands in sterile inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 14, 812–820 (2013).

Que, X. et al. Oxidized phospholipids are proinflammatory and proatherogenic in hypercholesterolaemic mice. Nature 558, 301–306 (2018).

Busch, C. J. et al. Malondialdehyde epitopes are sterile mediators of hepatic inflammation in hypercholesterolemic mice. Hepatology 65, 1181–1195 (2017).

Mallat, Z. & Binder, C. J. The why and how of adaptive immune responses in ischemic cardiovascular disease. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 1, 431–444 (2022).

Ito, A. et al. Cholesterol accumulation in CD11c+ immune cells is a causal and targetable factor in autoimmune disease. Immunity 45, 1311–1326 (2016).

Gil-Pulido, J. & Zernecke, A. Antigen-presenting dendritic cells in atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 816, 25–31 (2017).

Zhivaki, D. & Kagan, J. C. Innate immune detection of lipid oxidation as a threat assessment strategy. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 22, 322–330 (2022).

Saigusa, R., Winkels, H. & Ley, K. T cell subsets and functions in atherosclerosis. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 17, 387–401 (2020).

Saigusa, R. et al. Single cell transcriptomics and TCR reconstruction reveal CD4 T cell response to MHC-II-restricted APOB epitope in human cardiovascular disease. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 1, 462–475 (2022).

Kimura, T. et al. Regulatory CD4+ T cells recognize major histocompatibility complex class II molecule-restricted peptide epitopes of apolipoprotein B. Circulation 138, 1130–1143 (2018).

Freuchet, A. et al. Identification of human exTreg cells as CD16+CD56+ cytotoxic CD4+ T cells. Nat. Immunol. 24, 1748–1761 (2023).

Calabretta, R. et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy induces inflammatory activity in large arteries. Circulation 142, 2396–2398 (2020).

Drobni, Z. D. et al. Association between immune checkpoint inhibitors with cardiovascular events and atherosclerotic plaque. Circulation 142, 2299–2311 (2020).

Suero-Abreu, G. A., Zanni, M. V. & Neilan, T. G. Atherosclerosis with immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: evidence, diagnosis, and management: JACC: Cardiooncology State-of-the-Art Review. JACC CardioOncol 4, 598–615 (2022).

Vuong, J. T. et al. Immune checkpoint therapies and atherosclerosis: mechanisms and clinical implications: JACC State-of-the-Art Review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 79, 577–593 (2022).

Depuydt, M. A. C. et al. Single-cell T cell receptor sequencing of paired human atherosclerotic plaques and blood reveals autoimmune-like features of expanded effector T cells. Nat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2, 112–125 (2023).

Fernandez, D. M. & Giannarelli, C. Immune cell profiling in atherosclerosis: role in research and precision medicine. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 19, 43–58 (2022).

Schafer, S. & Zernecke, A. CD8+ T cells in atherosclerosis. Cells 10, 37 (2020).

Dimayuga, P. C. et al. Identification of apoB-100 peptide-specific CD8+ T cells in atherosclerosis. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 6, e005318 (2017).

Porsch, F., Mallat, Z. & Binder, C. J. Humoral immunity in atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction: from B cells to antibodies. Cardiovasc. Res. 117, 2544–2562 (2021).

Centa, M. et al. Acute loss of apolipoprotein E triggers an autoimmune response that accelerates atherosclerosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 38, e145–e158 (2018).

Porsch, F. & Binder, C. J. Autoimmune diseases and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21, 780–807 (2024).

Mackay, F. & Schneider, P. Cracking the BAFF code. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 491–502 (2009).

Yla-Herttuala, S. et al. Rabbit and human atherosclerotic lesions contain IgG that recognizes epitopes of oxidized LDL. Arterioscler. Thromb. 14, 32–40 (1994).

Taleb, A. et al. High immunoglobulin-M levels to oxidation-specific epitopes are associated with lower risk of acute myocardial infarction. J. Lipid Res. 64, 100391 (2023).

Morgan-Hughes, J. A. et al. The molecular pathology of human respiratory chain defects. Rev. Neurol. 147, 450–454 (1991).

Gruber, S. et al. Sialic acid-binding immunoglobulin-like lectin G promotes atherosclerosis and liver inflammation by suppressing the protective functions of B-1 cells. Cell Rep. 14, 2348–2361 (2016).

Chou, M. Y. et al. Oxidation-specific epitopes are dominant targets of innate natural antibodies in mice and humans. J. Clin. Invest. 119, 1335–1349 (2009).

Deroissart, J. & Binder, C. J. Mapping the functions of IgM antibodies in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 20, 433–434 (2023).

Srikakulapu, P. et al. Perivascular adipose tissue harbors atheroprotective IgM-producing B cells. Front. Physiol. 8, 719 (2017).

Bjornson, E. et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoprotein remnants, low-density lipoproteins, and risk of coronary heart disease: a UK Biobank study. Eur. Heart J. 44, 4186–4195 (2023).

Bjornson, E. et al. Lipoprotein(a) is markedly more atherogenic than LDL: an apolipoprotein B-based genetic analysis. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83, 385–395 (2024).

Ginsberg, H. N. et al. Triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants: metabolic insights, role in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, and emerging therapeutic strategies – a consensus statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society. Eur. Heart J. 42, 4791–4806 (2021).

Kronenberg, F. et al. Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: a European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement. Eur. Heart J. 43, 3925–3946 (2022).

Sacks, F. M. & Campos, H. Clinical review 163: cardiovascular endocrinology: low-density lipoprotein size and cardiovascular disease: a reappraisal. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 88, 4525–4532 (2003).

Chapman, M. J. et al. LDL subclass lipidomics in atherogenic dyslipidemia: effect of statin therapy on bioactive lipids and dense LDL. J. Lipid Res. 61, 911–932 (2020).

Krauss, R. M. Small dense low-density lipoprotein particles: clinically relevant? Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 33, 160–166 (2022).

Anber, V., Millar, J. S., McConnell, M., Shepherd, J. & Packard, C. J. Interaction of very-low-density, intermediate-density, and low-density lipoproteins with human arterial wall proteoglycans. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 17, 2507–2514 (1997).

Varbo, A. et al. Remnant cholesterol as a causal risk factor for ischemic heart disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 61, 427–436 (2013).

Ference, B. A. et al. Association of triglyceride-lowering LPL variants and LDL-C-lowering LDLR variants with risk of coronary heart disease. JAMA 321, 364–373 (2019).

Packard, C. J., Boren, J. & Taskinen, M. R. Causes and consequences of hypertriglyceridemia. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 252 (2020).

Björnson, E. et al. Quantifying triglyceride-rich lipoprotein atherogenicity, associations with inflammation, and implications for risk assessment using non-HDL cholesterol. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 84, 1328–1338 (2024).

Sacks, F. M. The crucial roles of apolipoproteins E and C-III in apoB lipoprotein metabolism in normolipidemia and hypertriglyceridemia. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 26, 56–63 (2015).

Brown, W. V., Sacks, F. M. & Sniderman, A. D. JCL roundtable: apolipoproteins as causative elements in vascular disease. J. Clin. Lipidol. 9, 733–740 (2015).

Boren, J., Packard, C. J. & Taskinen, M. R. The roles of ApoC-III on the metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins in humans. Front. Endocrinol. 11, 474 (2020).

Salinas, C. A. A. & Chapman, M. J. Remnant lipoproteins: are they equal to or more atherogenic than LDL? Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 31, 132–139 (2020).

Van Lenten, B. J. et al. Receptor-mediated uptake of remnant lipoproteins by cholesterol-loaded human monocyte-macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 260, 8783–8788 (1985).

Varbo, A. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Remnant lipoproteins. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 28, 300–307 (2017).

Navarese, E. P. et al. Independent causal effect of remnant cholesterol on atherosclerotic cardiovascular outcomes: a mendelian randomization study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 43, e373–e380 (2023).

Varbo, A., Benn, M., Tybjaerg-Hansen, A. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Elevated remnant cholesterol causes both low-grade inflammation and ischemic heart disease, whereas elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol causes ischemic heart disease without inflammation. Circulation 128, 1298–1309 (2013).

Wadstrom, B. N., Pedersen, K. M., Wulff, A. B. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Inflammation compared to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol: two different causes of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Curr. Opin. Lipidol. 34, 96–104 (2023).

Zewinger, S. et al. Apolipoprotein C3 induces inflammation and organ damage by alternative inflammasome activation. Nat. Immunol. 21, 30–41 (2020).

Schwartz, E. A. & Reaven, P. D. Lipolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins, vascular inflammation, and atherosclerosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1821, 858–866 (2012).

Higgins, L. J. & Rutledge, J. C. Inflammation associated with the postprandial lipolysis of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins by lipoprotein lipase. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 11, 199–205 (2009).

De Caterina, R., Liao, J. K. & Libby, P. Fatty acid modulation of endothelial activation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 71, 213S–223S (2000).

Cabodevilla, A. G. et al. Eruptive xanthoma model reveals endothelial cells internalize and metabolize chylomicrons, leading to extravascular triglyceride accumulation. J. Clin. Invest. 131, e145800 (2021).

Goldberg, I. J., Cabodevilla, A. G. & Younis, W. In the beginning, lipoproteins cross the endothelial barrier. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 31, 854–860 (2024).

Kontush, A. & Chapman, M. J. Lipidomics as a tool for the study of lipoprotein metabolism. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 12, 194–201 (2010).

Mucinski, J. M. et al. Relationships between very low-density lipoproteins-ceramides, -diacylglycerols, and -triacylglycerols in insulin-resistant men. Lipids 55, 387–393 (2020).

Nieddu, G. et al. Molecular characterization of plasma HDL, LDL, and VLDL lipids cargos from atherosclerotic patients with advanced carotid lesions: a preliminary report. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 12449 (2022).

Nordestgaard, B. G., & Tybjaerg-Hansen, A. IDL, VLDL, chylomicrons and atherosclerosis. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 8, 92–98 (1992).

Boutagy, N. E. et al. Dynamic metabolism of endothelial triglycerides protects against atherosclerosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 134, e170453 (2024).

Jaffe, I. Z. & Karumanchi, S. A. Lipid droplets in the endothelium: the missing link between metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease? J. Clin. Invest. 134, e176347 (2024).

Kim, B. et al. Endothelial lipid droplets suppress eNOS to link high fat consumption to blood pressure elevation. J. Clin. Invest. 133, e173160 (2023).

Doi, H. et al. Remnant lipoproteins induce proatherothrombogenic molecules in endothelial cells through a redox-sensitive mechanism. Circulation 102, 670–676 (2000).

de Sousa, J. C. et al. Association between coagulation factors VII and X with triglyceride rich lipoproteins. J. Clin. Pathol. 41, 940–944 (1988).

Tsimikas, S., Moriarty, P. M. & Stroes, E. S. Emerging RNA therapeutics to lower blood levels of Lp(a): JACC Focus Seminar 2/4. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77, 1576–1589 (2021).

Reyes-Soffer, G. et al. Lipoprotein(a): a genetically determined, causal, and prevalent risk factor for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 42, e48–e60 (2022).

Burgess, S. et al. Association of LPA variants with risk of coronary disease and the implications for lipoprotein(a)-lowering therapies: a mendelian randomization analysis. JAMA Cardiol. 3, 619–627 (2018).

Madsen, C. M., Kamstrup, P. R., Langsted, A., Varbo, A. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Lipoprotein(a)-lowering by 50 mg/dL (105 nmol/L) may be needed to reduce cardiovascular disease 20% in secondary prevention: a population-based study. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 40, 255–266 (2020).

Marston, N. A. et al. Per-particle cardiovascular risk of lipoprotein(a) vs Non-Lp(a) apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 83, 470–472 (2024).

Bjornson, E., Adiels, M., Boren, J. & Packard, C. J. Lipoprotein(a) is a highly atherogenic lipoprotein: pathophysiological basis and clinical implications. Curr. Opin. Cardiol. 39, 503–510 (2024).

Boffa, M. B. & Koschinsky, M. L. Oxidized phospholipids as a unifying theory for lipoprotein(a) and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 16, 305–318 (2019).

Rader, D. J. & Bajaj, A. Lipoprotein(a) and oxidized phospholipids: partners in crime or individual perpetrators in cardiovascular disease? J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 81, 1793–1796 (2023).

D’Angelo, A. et al. The apolipoprotein(a) component of lipoprotein(a) mediates binding to laminin: contribution to selective retention of lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic lesions. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1687, 1–10 (2005).

McLean, J. W. et al. cDNA sequence of human apolipoprotein(a) is homologous to plasminogen. Nature 330, 132–137 (1987).

Koschinsky, M. L., Stroes, E. S. G. & Kronenberg, F. Daring to dream: targeting lipoprotein(a) as a causal and risk-enhancing factor. Pharmacol. Res. 194, 106843 (2023).

Boffa, M. B. & Koschinsky, M. L. Lipoprotein (a): truly a direct prothrombotic factor in cardiovascular disease? J. Lipid Res. 57, 745–757 (2016).

Boffa, M. B. et al. Potent reduction of plasma lipoprotein (a) with an antisense oligonucleotide in human subjects does not affect ex vivo fibrinolysis. J. Lipid Res. 60, 2082–2089 (2019).

von Depka, M. et al. Increased lipoprotein (a) levels as an independent risk factor for venous thromboembolism. Blood 96, 3364–3368 (2000).

Nowak-Gottl, U. et al. Increased lipoprotein(a) is an important risk factor for venous thromboembolism in childhood. Circulation 100, 743–748 (1999).

Marcucci, R. et al. Increased plasma levels of lipoprotein(a) and the risk of idiopathic and recurrent venous thromboembolism. Am. J. Med. 115, 601–605 (2003).

Vormittag, R. et al. Lipoprotein (a) in patients with spontaneous venous thromboembolism. Thromb. Res. 120, 15–20 (2007).

Kronenberg, F. et al. Frequent questions and responses on the 2022 lipoprotein(a) consensus statement of the European Atherosclerosis Society. Atherosclerosis 374, 107–120 (2023).

Bergmark, C. et al. A novel function of lipoprotein [a] as a preferential carrier of oxidized phospholipids in human plasma. J. Lipid Res. 49, 2230–2239 (2008).

Leibundgut, G. et al. Determinants of binding of oxidized phospholipids on apolipoprotein (a) and lipoprotein (a). J. Lipid Res. 54, 2815–2830 (2013).

Nie, J., Yang, J., Wei, Y. & Wei, X. The role of oxidized phospholipids in the development of disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 76, 100909 (2020).

Assini, J. M. et al. High levels of lipoprotein(a) in transgenic mice exacerbate atherosclerosis and promote vulnerable plaque features in a sex-specific manner. Atherosclerosis 384, 117150 (2023).

Dzobo, K. E. et al. Diacylglycerols and lysophosphatidic acid, enriched on lipoprotein(a), contribute to monocyte inflammation. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 44, 720–740 (2024).

Mach, F. et al. 2019 ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. Eur. Heart J. 41, 111–188 (2020).

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaboration Efficacy and safety of LDL-lowering therapy among men and women: meta-analysis of individual data from 174,000 participants in 27 randomised trials. Lancet 385, 1397–1405 (2015).

Tsimikas, S. Lipoprotein(a) in the year 2024: a look back and a look ahead. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 44, 1485–1490 (2024).

Kim, N. H. & Kim, S. G. Fibrates revisited: potential role in cardiovascular risk reduction. Diabetes Metab. J. 44, 213–221 (2020).

Das Pradhan, A. et al. Triglyceride lowering with pemafibrate to reduce cardiovascular risk. N. Engl. J. Med. 387, 1923–1934 (2022).

Doi, T., Langsted, A. & Nordestgaard, B. G. Remnant cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, and apoB absolute mass changes explain results of the PROMINENT trial. Atherosclerosis 393, 117556 (2024).

Tokgozoglu, L., Pirillo, A. & Catapano, A. L. Disconnect between triglyceride reduction and cardiovascular outcomes: lessons from the PROMINENT and CLEAR Outcomes trials. Eur. Heart J. 45, 2377–2379 (2024).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed substantially to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Cardiology thanks Katariina Öörni and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Borén, J., Packard, C.J. & Binder, C.J. Apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins in atherogenesis. Nat Rev Cardiol 22, 399–413 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-024-01111-0

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-024-01111-0

This article is cited by

-

Association of apolipoprotein B and excess apolipoprotein B with cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study of the UK Biobank

Lipids in Health and Disease (2026)

-

Residual cardiovascular risk in coronary artery disease: from pathophysiology to established and novel therapies

Nature Reviews Cardiology (2026)

-

A practical guide to the management of dyslipidaemia

Clinical Research in Cardiology (2026)

-

Cholesterol metabolism: molecular mechanisms, biological functions, diseases, and therapeutic targets

Molecular Biomedicine (2025)

-

Engineered immune-driven theranostics for clinical cardiology

Military Medical Research (2025)