Abstract

Cancer of unknown primary (CUP) is a metastatic malignancy for which a primary site of origin cannot be identified despite a thorough and standardized diagnostic work-up, and accounts for 1–3% of all malignancies. An unfavourable subgroup of CUP has a poor prognosis, with a median overall survival of <1 year when treated with current standard-of-care platinum-based chemotherapy. Virtually no progress in elucidating the disease biology and improving outcomes for patients with unfavourable CUP has been made over the past several decades, including a failure of initial randomized clinical trials to demonstrate the superiority of tissue-of-origin (ToO) identification by gene-expression profiling and subsequent primary-site-directed treatment over standard chemotherapy. However, large-cohort randomized trials have now shown that molecularly guided therapy improves outcomes for patients with CUP harbouring an actionable target, both in a tissue-agnostic as well as a primary tumour site-specific context. Moreover, data from non-randomized phase II trials suggest that immunotherapy using immune-checkpoint inhibitors can be beneficial even in patients with CUP that has relapsed after, or is refractory to, standard chemotherapy. In addition, a plethora of refined and novel strategies, including DNA and RNA sequencing, DNA-methylation profiling, circulating tumour DNA analysis, and artificial intelligence-based pathology, have been leveraged to facilitate ToO identification. In light of these developments, we review current ToO methodologies and compare the evidence supporting the use of a primary tumour site-guided approach versus a histology-agnostic approach to the management of CUP. We also discuss whether CUP can be viewed as a model disease for the development of histology-agnostic precision oncology treatment strategies.

Key points

-

Several methods based on DNA or RNA sequencing, transcriptomics microarrays, DNA-methylation profiling, circulating tumour DNA analysis and artificial intelligence-based pathology have been developed to predict the tissue of origin (ToO) of cancer of unknown primary (CUP) with high accuracy; however, no benchmarking and reporting standards have been established to date, making it challenging to judge the value of different tests.

-

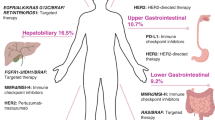

Next-generation sequencing can aid in the differential diagnosis, ToO identification and detection of therapeutic targets in patients with unfavourable CUP.

-

Randomized trials have revealed that molecularly guided therapy and immunotherapy improve progression-free survival compared with standard platinum-based chemotherapy in patients with newly diagnosed unfavourable CUP, in both ToO-informed and histology-agnostic settings.

-

Non-randomized trials suggest that second-line treatment with immune-checkpoint inhibitors can increase response rates and prolongs survival in patients with a high tumour mutational burden and/or PD-L1 expression.

-

Comprehensive genomic profiling should be performed at initial diagnosis in all patients with unfavourable CUP, and liquid biopsy circulating tumour DNA assays can overcome the technical difficulties and scarcity of tumour material commonly associated with tissue biopsy approaches.

-

Access to molecular testing as well as to molecularly guided treatment and immunotherapy for patients with CUP remains limited in many countries.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$189.00 per year

only $15.75 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Halsted, W. S. I. The results of radical operations for the cure of carcinoma of the breast. Ann. Surg. 46, 1–19 (1907).

Holmes, F. F. & Fouts, T. L. Metastatic cancer of unknown primary site. Cancer 26, 816–820 (1970).

Kramer, A. et al. Cancer of unknown primary: ESMO clinical practice guideline for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann. Oncol. 34, 228–246 (2023).

Binder, C., Matthes, K. L., Korol, D., Rohrmann, S. & Moch, H. Cancer of unknown primary-epidemiological trends and relevance of comprehensive genomic profiling. Cancer Med. 7, 4814–4824 (2018).

Hemminki, K., Bevier, M., Hemminki, A. & Sundquist, J. Survival in cancer of unknown primary site: population-based analysis by site and histology. Ann. Oncol. 23, 1854–1863 (2012).

Mileshkin, L. et al. Cancer-of-unknown-primary-origin: a SEER-medicare study of patterns of care and outcomes among elderly patients in clinical practice. Cancers 14, https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers14122905 (2022).

Pavlidis, N., Briasoulis, E., Hainsworth, J. & Greco, F. A. Diagnostic and therapeutic management of cancer of an unknown primary. Eur. J. Cancer 39, 1990–2005 (2003).

Briasoulis, E. et al. Carboplatin plus paclitaxel in unknown primary carcinoma: a phase II Hellenic Cooperative Oncology Group study. J. Clin. Oncol. 18, 3101–3107 (2000).

Greco, F. A. et al. Carcinoma of unknown primary site. Cancer 89, 2655–2660 (2000).

Greco, F. A. et al. Carcinoma of unknown primary site: phase II trials with docetaxel plus cisplatin or carboplatin. Ann. Oncol. 11, 211–215 (2000).

Hainsworth, J. D. & Greco, F. A. Treatment of patients with cancer of an unknown primary site. N. Engl. J. Med. 329, 257–263 (1993).

Culine, S. et al. Cisplatin in combination with either gemcitabine or irinotecan in carcinomas of unknown primary site: results of a randomized phase II study-trial for the French study group on carcinomas of unknown primary (GEFCAPI 01). J. Clin. Oncol. 21, 3479–3482 (2003).

Gross-Goupil, M. et al. Cisplatin alone or combined with gemcitabine in carcinomas of unknown primary: results of the randomised GEFCAPI 02 trial. Eur. J. Cancer 48, 721–727 (2012).

Hainsworth, J. D. et al. Molecular gene expression profiling to predict the tissue of origin and direct site-specific therapy in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site: a prospective trial of the Sarah Cannon Research Institute. J. Clin. Oncol. 31, 217–223 (2013).

Moran, S. et al. Epigenetic profiling to classify cancer of unknown primary: a multicentre, retrospective analysis. Lancet Oncol. 17, 1386–1395 (2016).

Hayashi, H. et al. Randomized phase II trial comparing site-specific treatment based on gene expression profiling with carboplatin and paclitaxel for patients with cancer of unknown primary site. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 570–579 (2019).

Fizazi, K. M. et al. I. A phase III trial of empiric chemotherapy with cisplatin and gemcitabine or systemic treatment tailored by molecular gene expression analysis in patients with carcinomas of an unknown primary (CUP) site (GEFCAPI 04). Ann. Oncol. 30, v851–v934 (2019).

Rassy, E. & Pavlidis, N. Progress in refining the clinical management of cancer of unknown primary in the molecular era. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 17, 541–554 (2020).

Pauli, C. et al. A challenging task: identifying patients with cancer of unknown primary (CUP) according to ESMO guidelines: the CUPISCO trial experience. Oncologist 26, e769–e779 (2021).

Pisacane, A. et al. Real-world histopathological approach to malignancy of undefined primary origin (MUO) to diagnose cancers of unknown primary (CUPs). Virchows Arch. 482, 463–475 (2023).

Beauchamp, K. et al. Carcinoma of unknown primary (CUP): an update for histopathologists. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 42, 1189–1200 (2023).

Ramos-Herberth, F. I., Karamchandani, J., Kim, J. & Dadras, S. S. SOX10 immunostaining distinguishes desmoplastic melanoma from excision scar. J. Cutan. Pathol. 37, 944–952 (2010).

Qaseem, A., Usman, N., Jayaraj, J. S., Janapala, R. N. & Kashif, T. Cancer of unknown primary: a review on clinical guidelines in the development and targeted management of patients with the unknown primary site. Cureus 11, e5552 (2019).

Ettinger, D. S. et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines occult primary. J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw. 9, 1358–1395 (2011).

Yoon, E. C. et al. TRPS1, GATA3, and SOX10 expression in triple-negative breast carcinoma. Hum. Pathol. 125, 97–107 (2022).

Gurel, B. et al. NKX3.1 as a marker of prostatic origin in metastatic tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 34, 1097–1105 (2010).

Lugli, A., Tzankov, A., Zlobec, I. & Terracciano, L. M. Differential diagnostic and functional role of the multi-marker phenotype CDX2/CK20/CK7 in colorectal cancer stratified by mismatch repair status. Mod. Pathol. 21, 1403–1412 (2008).

Velut, Y. et al. SMARCA4-deficient lung carcinoma is an aggressive tumor highly infiltrated by FOXP3+ cells and neutrophils. Lung Cancer 169, 13–21 (2022).

Herpel, E. et al. SMARCA4 and SMARCA2 deficiency in non-small cell lung cancer: immunohistochemical survey of 316 consecutive specimens. Ann. Diagn. Pathol. 26, 47–51 (2017).

Noh, S. & Shim, H. Optimal combination of immunohistochemical markers for subclassification of non-small cell lung carcinomas: a tissue microarray study of poorly differentiated areas. Lung Cancer 76, 51–55 (2012).

Labib, O. H. et al. The diagnostic value of arginase-1, FTCD, and MOC-31 expression in early detection of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and in differentiation between HCC and metastatic adenocarcinoma to the liver. J. Gastrointest. Cancer 51, 88–101 (2020).

Gorbokon, N. et al. PAX8 expression in cancerous and non-neoplastic tissue: a tissue microarray study on more than 17,000 tumors from 149 different tumor entities. Virchows Arch. 485, 491–507 (2024).

Miettinen, M. et al. SALL4 expression in germ cell and non-germ cell tumors: a systematic immunohistochemical study of 3215 cases. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 38, 410–420 (2014).

Haberecker, M., Topfer, A., Melega, F., Moch, H. & Pauli, C. A systematic comparison of pan-Trk immunohistochemistry assays among multiple cancer types. Histopathology 82, 1003–1012 (2023).

Shreenivas, A. et al. ALK fusions in the pan-cancer setting: another tumor-agnostic target? NPJ Precis. Oncol. 7, 101 (2023).

Meric-Bernstam, F. et al. Efficacy and safety of trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2-expressing solid tumors: primary results from the DESTINY-PanTumor02 phase II trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 47–58 (2024).

Tanizaki, J. et al. Open-label phase II study of the efficacy of nivolumab for cancer of unknown primary. Ann. Oncol. 33, 216–226 (2022).

Bochtler, T. et al. Integrated histogenetic analysis reveals BAP1-mutated epithelioid mesothelioma in a patient with cancer of unknown primary. J. Natl Compr. Canc. Netw. 16, 677–682 (2018).

Bochtler, T. et al. Comparative genetic profiling aids diagnosis and clinical decision making in challenging cases of CUP syndrome. Int. J. Cancer 145, 2963–2973 (2019).

Kramer, A. et al. Molecularly guided therapy versus chemotherapy after disease control in unfavourable cancer of unknown primary (CUPISCO): an open-label, randomised, phase 2 study. Lancet 404, 527–539 (2024).

Fusco, M. J. et al. Evaluation of targeted next-generation sequencing for the management of patients diagnosed with a cancer of unknown primary. Oncologist 27, e9–e17 (2022).

Varghese, A. M. et al. Clinical and molecular characterization of patients with cancer of unknown primary in the modern era. Ann. Oncol. 28, 3015–3021 (2017).

Ross, J. S. et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of carcinoma of unknown primary origin: retrospective molecular classification considering the CUPISCO study design. Oncologist 26, e394–e402 (2021).

Westphalen, C. B. et al. Baseline mutational profiles of patients with carcinoma of unknown primary origin enrolled in the CUPISCO study. ESMO Open 8, 102035 (2023).

Pouyiourou, M. et al. Nivolumab and ipilimumab in recurrent or refractory cancer of unknown primary: a phase II trial. Nat. Commun. 14, 6761 (2023).

Bochtler, T. et al. Prognostic impact of copy number alterations and tumor mutational burden in carcinoma of unknown primary. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 61, 551–560 (2022).

Gatalica, Z., Xiu, J., Swensen, J. & Vranic, S. Comprehensive analysis of cancers of unknown primary for the biomarkers of response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Eur. J. Cancer 94, 179–186 (2018).

Moser, T. & Heitzer, E. Surpassing sensitivity limits in liquid biopsy. Science 383, 260–261 (2024).

Alix-Panabieres, C. & Pantel, K. Advances in liquid biopsy: from exploration to practical application. Cancer Cell https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccell.2024.11.009 (2024).

Kato, S. et al. Utility of genomic analysis in circulating tumor DNA from patients with carcinoma of unknown primary. Cancer Res. 77, 4238–4246 (2017).

Kato, S. et al. Therapeutic actionability of circulating cell-free DNA alterations in carcinoma of unknown primary. JCO Precis. Oncol. 5, PO.21.00011 (2021).

Bayle, A. et al. Liquid versus tissue biopsy for detecting actionable alterations according to the ESMO scale for clinical actionability of molecular targets in patients with advanced cancer: a study from the French National Center for Precision Medicine (PRISM). Ann. Oncol. 33, 1328–1331 (2022).

Raez, L. E. et al. Liquid biopsy versus tissue biopsy to determine front line therapy in metastatic non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Clin. Lung Cancer 24, 120–129 (2023).

Park, S. et al. High concordance of actionable genomic alterations identified between circulating tumor DNA-based and tissue-based next-generation sequencing testing in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: the Korean Lung Liquid Versus Invasive Biopsy Program. Cancer 127, 3019–3028 (2021).

Benavides, M. et al. Clinical utility of comprehensive circulating tumor DNA genotyping compared with standard of care tissue testing in patients with newly diagnosed metastatic colorectal cancer. ESMO Open 7, 100481 (2022).

Laprovitera, N. et al. Genetic characterization of cancer of unknown primary using liquid biopsy approaches. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 9, 666156 (2021).

Pouyiourou, M. et al. Frequency and prognostic value of circulating tumor cells in cancer of unknown primary. Clin. Chem. 70, 297–306 (2024).

Zhu, L. & Wang, N. 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography-computed tomography as a diagnostic tool in patients with cervical nodal metastases of unknown primary site: a meta-analysis. Surg. Oncol. 22, 190–194 (2013).

Roh, J. L. et al. Utility of combined 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography and computed tomography in patients with cervical metastases from unknown primary tumors. Oral. Oncol. 45, 218–224 (2009).

Rusthoven, K. E., Koshy, M. & Paulino, A. C. The role of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in cervical lymph node metastases from an unknown primary tumor. Cancer 101, 2641–2649 (2004).

Moller, A. K. et al. A prospective comparison of 18F-FDG PET/CT and CT as diagnostic tools to identify the primary tumor site in patients with extracervical carcinoma of unknown primary site. Oncologist 17, 1146–1154 (2012).

Sivakumaran, T. et al. Evaluating the utility of 18F-FDG PET/CT in cancer of unknown primary. J. Nucl. Med. 65, 1557–1563 (2024).

Soni, N. et al. Role of FDG PET/CT for detection of primary tumor in patients with extracervical metastases from carcinoma of unknown primary. Clin. Imaging 78, 262–270 (2021).

Moller, A. K. et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT as a diagnostic tool in patients with extracervical carcinoma of unknown primary site: a literature review. Oncologist 16, 445–451 (2011).

Burglin, S. A., Hess, S., Hoilund-Carlsen, P. F. & Gerke, O. 18F-FDG PET/CT for detection of the primary tumor in adults with extracervical metastases from cancer of unknown primary: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 96, e6713 (2017).

Gu, B. et al. Imaging of tumor stroma using 68Ga-FAPI PET/CT to improve diagnostic accuracy of primary tumors in head and neck cancer of unknown primary: a comparative imaging trial. J. Nucl. Med. 65, 365–371 (2024).

Bazarbachi, A. H., Magrini, N., Aziz, Z. & Fojo, T. Evidence for a reduction in number of cycles of immune checkpoint inhibitors. Lancet Oncol. 26, 9–11 (2025).

Robert, C. et al. Seven-year follow-up of the phase III KEYNOTE-006 study: pembrolizumab versus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 41, 3998–4003 (2023).

Schank, T. E. et al. Complete metabolic response in FDG-PET-CT scan before discontinuation of immune checkpoint inhibitors correlates with long progression-free survival. Cancers 13, 2616 (2021).

Tan, A. C. et al. FDG-PET response and outcome from anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Ann. Oncol. 29, 2115–2120 (2018).

Handorf, C. R. et al. A multicenter study directly comparing the diagnostic accuracy of gene expression profiling and immunohistochemistry for primary site identification in metastatic tumors. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 37, 1067–1075 (2013).

Tothill, R. W. et al. An expression-based site of origin diagnostic method designed for clinical application to cancer of unknown origin. Cancer Res. 65, 4031–4040 (2005).

Monzon, F. A. et al. Multicenter validation of a 1,550-gene expression profile for identification of tumor tissue of origin. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 2503–2508 (2009).

Pillai, R. et al. Validation and reproducibility of a microarray-based gene expression test for tumor identification in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded specimens. J. Mol. Diagn. 13, 48–56 (2011).

Tothill, R. W. et al. Development and validation of a gene expression tumour classifier for cancer of unknown primary. Pathology 47, 7–12 (2015).

Posner, A. et al. A comparison of DNA sequencing and gene expression profiling to assist tissue of origin diagnosis in cancer of unknown primary. J. Pathol. 259, 81–92 (2023).

Fuentes Bayne, H. E. et al. Personalized therapy selection by integration of molecular cancer classification by the 92-gene assay and tumor profiling in patients with cancer of unknown primary. JCO Precis. Oncol. 8, e2400191 (2024).

Ye, Q. et al. Development and clinical validation of a 90-gene expression assay for identifying tumor tissue origin. J. Mol. Diagn. 22, 1139–1150 (2020).

Ma, X. J. et al. Molecular classification of human cancers using a 92-gene real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction assay. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 130, 465–473 (2006).

Erlander, M. G. et al. Performance and clinical evaluation of the 92-gene real-time PCR assay for tumor classification. J. Mol. Diagn. 13, 493–503 (2011).

Kerr, S. E. et al. Multisite validation study to determine performance characteristics of a 92-gene molecular cancer classifier. Clin. Cancer Res. 18, 3952–3960 (2012).

Kurahashi, I. et al. A microarray-based gene expression analysis to identify diagnostic biomarkers for unknown primary cancer. PLoS ONE 8, e63249 (2013).

Liu, X. et al. Site-specific therapy guided by a 90-gene expression assay versus empirical chemotherapy in patients with cancer of unknown primary (Fudan CUP-001): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 25, 1092–1102 (2024).

Grewal, J. K. et al. Application of a neural network whole transcriptome-based pan-cancer method for diagnosis of primary and metastatic cancers. JAMA Netw. Open 2, e192597 (2019).

Zhao, Y. et al. CUP-AI-Dx: a tool for inferring cancer tissue of origin and molecular subtype using RNA gene-expression data and artificial intelligence. EBioMedicine 61, 103030 (2020).

Michuda, J. et al. Validation of a transcriptome-based assay for classifying cancers of unknown primary origin. Mol. Diagn. Ther. 27, 499–511 (2023).

He, B. et al. A cross-cohort computational framework to trace tumor tissue-of-origin based on RNA sequencing. Sci. Rep. 13, 15356 (2023).

Hong, J., Hachem, L. D. & Fehlings, M. G. A deep learning model to classify neoplastic state and tissue origin from transcriptomic data. Sci. Rep. 12, 9669 (2022).

Capper, D. et al. DNA methylation-based classification of central nervous system tumours. Nature 555, 469–474 (2018).

Zhang, S. et al. DNA methylation profiling to determine the primary sites of metastatic cancers using formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues. Nat. Commun. 14, 5686 (2023).

Conway, A. M. et al. A cfDNA methylation-based tissue-of-origin classifier for cancers of unknown primary. Nat. Commun. 15, 3292 (2024).

De Wilde, J. et al. A fast, affordable, and minimally invasive diagnostic test for cancer of unknown primary using DNA methylation profiling. Lab. Invest. 104, 102091 (2024).

Moon, I. et al. Machine learning for genetics-based classification and treatment response prediction in cancer of unknown primary. Nat. Med. 29, 2057–2067 (2023).

Darmofal, M. et al. Deep-learning model for tumor-type prediction using targeted clinical genomic sequencing data. Cancer Discov. 14, 1064–1081 (2024).

Penson, A. et al. Development of genome-derived tumor type prediction to inform clinical cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 6, 84–91 (2020).

Mohrmann, L. et al. Comprehensive genomic and epigenomic analysis in cancer of unknown primary guides molecularly-informed therapies despite heterogeneity. Nat. Commun. 13, 4485 (2022).

Schipper, L. J. et al. Complete genomic characterization in patients with cancer of unknown primary origin in routine diagnostics. ESMO Open 7, 100611 (2022).

Nguyen, L., Van Hoeck, A. & Cuppen, E. Machine learning-based tissue of origin classification for cancer of unknown primary diagnostics using genome-wide mutation features. Nat. Commun. 13, 4013 (2022).

Chakraborty, S., Martin, A., Guan, Z., Begg, C. B. & Shen, R. Mining mutation contexts across the cancer genome to map tumor site of origin. Nat. Commun. 12, 3051 (2021).

Rebello, R. J. et al. Whole genome sequencing improves tissue-of-origin diagnosis and treatment options for cancer of unknown primary. Nat. Commun. 16, 4422 (2025).

Soh, K. P., Szczurek, E., Sakoparnig, T. & Beerenwinkel, N. Predicting cancer type from tumour DNA signatures. Genome Med. 9, 104 (2017).

Jiao, W. et al. A deep learning system accurately classifies primary and metastatic cancers using passenger mutation patterns. Nat. Commun. 11, 728 (2020).

Salvadores, M., Mas-Ponte, D. & Supek, F. Passenger mutations accurately classify human tumors. PLoS Comput. Biol. 15, e1006953 (2019).

Moor, M. et al. Foundation models for generalist medical artificial intelligence. Nature 616, 259–265 (2023).

Tian, F. et al. Prediction of tumor origin in cancers of unknown primary origin with cytology-based deep learning. Nat. Med. 30, 1309–1319 (2024).

Lu, M. Y. et al. AI-based pathology predicts origins for cancers of unknown primary. Nature 594, 106–110 (2021).

Lu, M. Y. et al. A visual-language foundation model for computational pathology. Nat. Med. 30, 863–874 (2024).

Chen, R. J. et al. Towards a general-purpose foundation model for computational pathology. Nat. Med. 30, 850–862 (2024).

Massard, C., Loriot, Y. & Fizazi, K. Carcinomas of an unknown primary origin-diagnosis and treatment. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 8, 701–710 (2011).

Huebner, G. et al. Paclitaxel and carboplatin vs gemcitabine and vinorelbine in patients with adeno- or undifferentiated carcinoma of unknown primary: a randomised prospective phase II trial. Br. J. Cancer 100, 44–49 (2009).

Pentheroudakis, G. et al. Docetaxel and carboplatin combination chemotherapy as outpatient palliative therapy in carcinoma of unknown primary: a multicentre Hellenic cooperative oncology group phase II study. Acta Oncol. 47, 1148–1155 (2008).

Mukai, H., Katsumata, N., Ando, M. & Watanabe, T. Safety and efficacy of a combination of docetaxel and cisplatin in patients with unknown primary cancer. Am. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 32–35 (2010).

Randen, M., Rutqvist, L. E. & Johansson, H. Cancer patients without a known primary: incidence and survival trends in Sweden 1960-2007. Acta Oncol. 48, 915–920 (2009).

Culine, S., Ychou, M., Fabbro, M., Romieu, G. & Cupissol, D. 5-fluorouracil and leucovorin as second-line chemotherapy in carcinomas of unknown primary site. Anticancer. Res. 21, 1455–1457 (2001).

Hainsworth, J. D. et al. Gemcitabine in the second-line therapy of patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site: a phase II trial of the Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network. Cancer Invest. 19, 335–339 (2001).

Hainsworth, J. D. et al. Oxaliplatin and capecitabine in the treatment of patients with recurrent or refractory carcinoma of unknown primary site: a phase 2 trial of the Sarah Cannon Oncology Research Consortium. Cancer 116, 2448–2454 (2010).

Hainsworth, J. D. et al. Combination chemotherapy with gemcitabine and irinotecan in patients with previously treated carcinoma of an unknown primary site: a Minnie Pearl Cancer Research Network phase II trial. Cancer 104, 1992–1997 (2005).

Moller, A. K., Pedersen, K. D., Abildgaard, J., Petersen, B. L. & Daugaard, G. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin as second-line treatment in patients with carcinoma of unknown primary site. Acta Oncol. 49, 431–435 (2010).

Hayashi, H. et al. Site-specific and targeted therapy based on molecular profiling by next-generation sequencing for cancer of unknown primary site: a nonrandomized phase 2 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 6, 1931–1938 (2020).

Greco, F. A., Labaki, C. & Rassy, E. Molecular diagnosis and site-specific therapy in cancer of unknown primary: an important milestone. Lancet Oncol. 25, 955–956 (2024).

Rassy, E. & Andre, F. New clinical trials in CUP and a novel paradigm in cancer classification. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 21, 833–834 (2024).

van Mourik, A. et al. Six-year experience of Australia’s first dedicated cancer of unknown primary clinic. Br. J. Cancer 129, 301–308 (2023).

Bochtler, T. et al. Outcomes of patients (pts) with unfavourable, non-squamous cancer of unknown primary (CUP) progressing after induction chemotherapy (CTX) in the global, open-label, phase II CUPISCO study. Ann. Oncol. 35, S296–S297 (2024).

Mosele, M. F. et al. Recommendations for the use of next-generation sequencing (NGS) for patients with advanced cancer in 2024: a report from the ESMO Precision Medicine Working Group. Ann. Oncol. 35, 588–606 (2024).

Botticelli, A. et al. The Rome trial from histology to target: the road to personalize targeted therapy and immunotherapy. Ann. Oncol. 35, 1202 (2024).

Huey, R. W. et al. Feasibility and value of genomic profiling in cancer of unknown primary: real-world evidence from prospective profiling study. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 115, 994–997 (2023).

Marchetti, P. et al. Combined tissue and liquid biopsy improves outcomes in advanced solid tumors: an exploratory analysis of the ROME trial. Cancer Res. 85, 6372 (2025).

Massard, C. et al. High-throughput genomics and clinical outcome in hard-to-treat advanced cancers: results of the MOSCATO 01 trial. Cancer Discov. 7, 586–595 (2017).

Le Tourneau, C. et al. Molecularly targeted therapy based on tumour molecular profiling versus conventional therapy for advanced cancer (SHIVA): a multicentre, open-label, proof-of-concept, randomised, controlled phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 16, 1324–1334 (2015).

Budczies, J. et al. Tumour mutational burden: clinical utility, challenges and emerging improvements. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 21, 725–742 (2024).

Gandara, D. R. et al. Tumor mutational burden and survival on immune checkpoint inhibition in >8000 patients across 24 cancer types. J. Immunother. Cancer 13, e010311 (2025).

Raghav, K. P. et al. Efficacy of pembrolizumab in patients with advanced cancer of unknown primary (CUP): a phase 2 non-randomized clinical trial. J. Immunother. Cancer 10, e004822 (2022).

Posner, A. et al. Immune and genomic biomarkers of immunotherapy response in cancer of unknown primary. J. Immunother. Cancer 11, e005809 (2023).

Fuentes, H. E. et al. Outcomes and molecular profiles in sarcomatoid carcinoma of unknown primary: the Mayo Clinic experience. Oncologist https://doi.org/10.1093/oncolo/oyae333 (2024).

Andre, F., Rassy, E., Marabelle, A., Michiels, S. & Besse, B. Forget lung, breast or prostate cancer: why tumour naming needs to change. Nature 626, 26–29 (2024).

Ilie, M., Heeke, S., Horgan, D. & Hofman, P. Navigating change in tumor naming: exploring the complexities and considerations of shifting toward molecular classifications. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 3183–3186 (2024).

Stenzinger, A. & Klauschen, F. Forget lung, breast or prostate cancer? Why we shouldn’t abandon tumour names yet. Nature 627, 38 (2024).

Larkin, J., Beland, C., Ramalingam, S. & Lyon, A. R. Personalized cancer care can’t rely on molecular testing alone. Nature 627, 38 (2024).

Zheng, C. & Xu, R. Predicting cancer origins with a DNA methylation-based deep neural network model. PLoS ONE 15, e0226461 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. HiTAIC: hierarchical tumor artificial intelligence classifier traces tissue of origin and tumor type in primary and metastasized tumors using DNA methylation. Nar. Cancer 5, zcad017 (2023).

Sun, M. et al. Tissue of origin prediction for cancer of unknown primary using a targeted methylation sequencing panel. Clin. Epigenetics 16, 25 (2024).

Tothill, R. W. et al. Massively-parallel sequencing assists the diagnosis and guided treatment of cancers of unknown primary. J. Pathol. 231, 413–423 (2013).

Liang, Y. et al. A deep learning framework to predict tumor tissue-of-origin based on copy number alteration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 8, 701 (2020).

He, B. et al. A machine learning framework to trace tumor tissue-of-origin of 13 types of cancer based on DNA somatic mutation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1866, 165916 (2020).

Abraham, J. et al. Machine learning analysis using 77,044 genomic and transcriptomic profiles to accurately predict tumor type. Transl. Oncol. 14, 101016 (2021).

Chen, K. et al. A molecular approach integrating genomic and DNA methylation profiling for tissue of origin identification in lung-specific cancer of unknown primary. J. Transl. Med. 20, 158 (2022).

Tanizaki, J. et al. Nivolumab for cancer of unknown primary (CUP): clinical efficacy and biomarker analysis from NivoCUP2 expanded access program (WJOG14620M). Ann. Oncol. 35, S305–S306 (2024).

Subbiah, V. et al. FIGHT-101, a first-in-human study of potent and selective FGFR 1-3 inhibitor pemigatinib in pan-cancer patients with FGF/FGFR alterations and advanced malignancies. Ann. Oncol. 33, 522–533 (2022).

Pant, S. et al. Erdafitinib in patients with advanced solid tumours with FGFR alterations (RAGNAR): an international, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol. 24, 925–935 (2023).

Rodón, J. et al. Pemigatinib in previously treated solid tumors with activating FGFR1–FGFR3 alterations: phase 2 FIGHT-207 basket trial. Nat. Med. 30, 1645–1654 (2024).

Smit, E. F. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer (DESTINY-Lung01): primary results of the HER2-overexpressing cohorts from a single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 25, 439–454 (2024).

Raghav, K. et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in patients with HER2-positive advanced colorectal cancer (DESTINY-CRC02): primary results from a multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 25, 1147–1162 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The work of M.P. was supported by the physician scientist programme of the Medical Faculty of the University of Heidelberg. The work of A.K. is funded by the Priority Program Translational Oncology of the Deutsche Krebshilfe (grant 70115167) and the proof-of-concept trial programme of the National Center for Tumour Diseases (NCT) Heidelberg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.P., C.P., K.P., A.S. and A.K. researched data for the article and wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to discussions of content and reviewed and/or edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

T.B. has received travel support from F. Hoffmann-La Roche and served as study oncologist for the CUPISCO trial (which was sponsored by F. Hoffmann-La Roche). C.P. has received research funding from F. Hoffmann-La Roche and served as study pathologist for the CUPISCO trial. H.M. has received research funding and honoraria for lectures from, and has served as a consultant on data safety monitoring boards or advisory boards for Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, F. Hoffmann-La Roche, Merck and Stemline Therapeutics. K.P. has received honoraria from Eppendorf, Menarini, MSD, NRICH, Roche and Sysmex. A.S. has acted as adviser for Aignostics, Amgen, Astellas, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Beigene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, Illumina, Incyte, Janssen, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, MSD, Novartis, Pfizer, Qlucore, Roche, Sanofi, Servier, Takeda and Thermo Fisher, and has received research funding from Bayer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Chugai and Incyte. A.K. has received research funding from Bristol Myers Squibb, F. Hoffmann-La Roche and Molecular Health; consulting fees, travel support and/or remuneration for advisory board participation from F. Hoffmann-La Roche; and served as study oncologist for the CUPISCO trial. M.P. and A.B. declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology thanks R. Tothill and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Pouyiourou, M., Bochtler, T., Pauli, C. et al. Rethinking cancer of unknown primary: from diagnostic challenge to targeted treatment. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 22, 781–799 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-025-01060-8

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-025-01060-8

This article is cited by

-

Bridging the gap: targeted treatment strategies for cancer of unknown primary

memo - Magazine of European Medical Oncology (2026)