Abstract

Human height is a model polygenic trait — additive effects of many individual variants create continuous, genetically determined variation in this phenotype. Height can also be severely affected by single-gene variants in monogenic disorders, often causing severe alterations in stature relative to population averages. Deciphering the genetic basis of height provides understanding into the biology of growth and is also of relevance to disease, as increased or decreased height relative to population averages has been epidemiologically and genetically associated with an altered risk of cancer or cardiometabolic diseases. With recent large-scale genome-wide association studies of human height reaching saturation, its genetic architecture has become clearer. Genes implicated by both monogenic and polygenic studies converge on common developmental or cellular pathways that affect stature, including at the growth plate, a key site of skeletal growth. In this Review, we summarize the genetic contributors to height, from ultra-rare monogenic disorders that severely affect growth to common alleles that act across multiple pathways.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Tanner, J. M. A History of the Study of Human Growth (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1981).

Galton, F. Regression towards mediocrity in hereditary stature. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 5, 329–348 (1885).

Rimoin, D. L., Merimee, T. J., Rabinowitz, D. & McKusick, V. A. Genetic aspects of clinical endocrinology. Recent Prog. Horm. Res. 24, 365–437 (1968).

Fisher, R. A. The correlation between relatives on the supposition of Mendelian inheritance. Trans. R. Soc. Edinb. 52, 399–433 (1918).

Polderman, T. J. et al. Meta-analysis of the heritability of human traits based on fifty years of twin studies. Nat. Genet. 47, 702–709 (2015).

Silventoinen, K. et al. Heritability of adult body height: a comparative study of twin cohorts in eight countries. Twin Res. 6, 399–408 (2003).

Perkins, J. M., Subramanian, S. V., Davey Smith, G. & Ozaltin, E. Adult height, nutrition, and population health. Nutr. Rev. 74, 149–165 (2016).

Kannam, J. P., Levy, D., Larson, M. & Wilson, P. W. Short stature and risk for mortality and cardiovascular disease events. The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 90, 2241–2247 (1994).

Njolstad, I., Arnesen, E. & Lund-Larsen, P. G. Sex differences in risk factors for clinical diabetes mellitus in a general population: a 12-year follow-up of the Finnmark Study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 147, 49–58 (1998).

Lai, F. Y. et al. Adult height and risk of 50 diseases: a combined epidemiological and genetic analysis. BMC Med. 16, 187 (2018).

Raghavan, S. et al. A multi-population phenome-wide association study of genetically-predicted height in the Million Veteran Program. PLoS Genet. 18, e1010193 (2022).

Tripaldi, R., Stuppia, L. & Alberti, S. Human height genes and cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1836, 27–41 (2013).

Albanes, D., Jones, D. Y., Schatzkin, A., Micozzi, M. S. & Taylor, P. R. Adult stature and risk of cancer. Cancer Res. 48, 1658–1662 (1988).

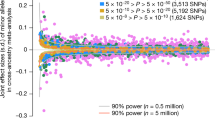

Yengo, L. et al. A saturated map of common genetic variants associated with human height. Nature 610, 704–712 (2022). The most comprehensive map to date of genome-wide association study signals associated with height.

Unger, S. et al. Nosology of genetic skeletal disorders: 2023 revision. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 191, 1164–1209 (2023).

Ranke, M. B. & Wit, J. M. Growth hormone — past, present and future. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 14, 285–300 (2018).

Amselem, S. et al. Laron dwarfism and mutations of the growth hormone-receptor gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 321, 989–995 (1989). Together with Godowski et al. (1989), the first reports linking variants in genes encoding the growth hormone pathway with monogenic forms of short stature.

Godowski, P. J. et al. Characterization of the human growth hormone receptor gene and demonstration of a partial gene deletion in two patients with Laron-type dwarfism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 86, 8083–8087 (1989). Together with Amselem et al. (1989), the first reports linking variants in genes encoding the growth hormone pathway with monogenic forms of short stature.

Begemann, M. et al. Paternally inherited IGF2 mutation and growth restriction. N. Engl. J. Med. 373, 349–356 (2015).

Domene, H. M. et al. Deficiency of the circulating insulin-like growth factor system associated with inactivation of the acid-labile subunit gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 350, 570–577 (2004).

Kofoed, E. M. et al. Growth hormone insensitivity associated with a STAT5b mutation. N. Engl. J. Med. 349, 1139–1147 (2003).

Woods, K. A., Camacho-Hubner, C., Savage, M. O. & Clark, A. J. Intrauterine growth retardation and postnatal growth failure associated with deletion of the insulin-like growth factor I gene. N. Engl. J. Med. 335, 1363–1367 (1996).

Dattani, M. T. & Malhotra, N. A review of growth hormone deficiency. Paediatr. Child Health 29, 285–292 (2019).

Guevara-Aguirre, J. et al. Despite higher body fat content, Ecuadorian subjects with Laron syndrome have less insulin resistance and lower incidence of diabetes than their relatives. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 28, 76–78 (2016).

Laron, Z. & Kauli, R. Fifty seven years of follow-up of the Israeli cohort of Laron Syndrome patients — from discovery to treatment. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 28, 53–56 (2016). This paper describes a comprehensive survey of individuals with Laron syndrome, including apparent protection from cancer.

Savarirayan, R. et al. Growth parameters in children with achondroplasia: a 7-year, prospective, multinational, observational study. Genet. Med. 24, 2444–2452 (2022).

Harada, D. et al. Final adult height in long-term growth hormone-treated achondroplasia patients. Eur. J. Pediatr. 176, 873–879 (2017).

Shiang, R. et al. Mutations in the transmembrane domain of FGFR3 cause the most common genetic form of dwarfism, achondroplasia. Cell 78, 335–342 (1994).

Rousseau, F. et al. Mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in achondroplasia. Nature 371, 252–254 (1994).

Savarirayan, R. et al. International consensus statement on the diagnosis, multidisciplinary management and lifelong care of individuals with achondroplasia. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol. 18, 173–189 (2022).

Cheung, M. S. et al. Growth reference charts for children with hypochondroplasia. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 194, 243–252 (2024).

French, T. & Savarirayan, R. in GeneReviews® (eds Adam, M. P. et al.) (Univ. of Washington, Seattle, 1993).

Kant, S. G. et al. A novel variant of FGFR3 causes proportionate short stature. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 172, 763–770 (2015).

Mamada, M. et al. Prevalence of mutations in the FGFR3 gene in individuals with idiopathic short stature. Clin. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 15, 61–64 (2006).

Costantini, A., Guasto, A. & Cormier-Daire, V. TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways in skeletal dysplasia with short and tall stature. Annu. Rev. Genomics Hum. Genet. 24, 225–253 (2023).

Wu, M., Wu, S., Chen, W. & Li, Y. P. The roles and regulatory mechanisms of TGF-β and BMP signaling in bone and cartilage development, homeostasis and disease. Cell Res. 34, 101–123 (2024).

Bartels, C. F. et al. Mutations in the transmembrane natriuretic peptide receptor NPR-B impair skeletal growth and cause acromesomelic dysplasia, type Maroteaux. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 75, 27–34 (2004).

Hisado-Oliva, A. et al. Mutations in C-natriuretic peptide (NPPC): a novel cause of autosomal dominant short stature. Genet. Med. 20, 91–97 (2018).

Vasques, G. A. et al. Heterozygous mutations in natriuretic peptide receptor-B (NPR2) gene as a cause of short stature in patients initially classified as idiopathic short stature. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98, E1636–E1644 (2013).

Hannema, S. E. et al. An activating mutation in the kinase homology domain of the natriuretic peptide receptor-2 causes extremely tall stature without skeletal deformities. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 98, E1988–E1998 (2013).

Miura, K. et al. An overgrowth disorder associated with excessive production of cGMP due to a gain-of-function mutation of the natriuretic peptide receptor 2 gene. PLoS ONE 7, e42180 (2012).

Boudin, E. et al. Bi-allelic loss-of-function mutations in the NPR-C receptor result in enhanced growth and connective tissue abnormalities. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 103, 288–295 (2018).

Bocciardi, R. et al. Overexpression of the C-type natriuretic peptide (CNP) is associated with overgrowth and bone anomalies in an individual with balanced t(2;7) translocation. Hum. Mutat. 28, 724–731 (2007).

Arnold, A. et al. Mutation of the signal peptide-encoding region of the preproparathyroid hormone gene in familial isolated hypoparathyroidism. J. Clin. Invest. 86, 1084–1087 (1990).

Duchatelet, S., Ostergaard, E., Cortes, D., Lemainque, A. & Julier, C. Recessive mutations in PTHR1 cause contrasting skeletal dysplasias in Eiken and Blomstrand syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 1–5 (2005).

Jobert, A. S. et al. Absence of functional receptors for parathyroid hormone and parathyroid hormone-related peptide in Blomstrand chondrodysplasia. J. Clin. Invest. 102, 34–40 (1998).

Schipani, E., Kruse, K. & Juppner, H. A constitutively active mutant PTH-PTHrP receptor in Jansen-type metaphyseal chondrodysplasia. Science 268, 98–100 (1995).

Minina, E. et al. BMP and Ihh/PTHrP signaling interact to coordinate chondrocyte proliferation and differentiation. Development 128, 4523–4534 (2001).

Lanske, B. et al. PTH/PTHrP receptor in early development and Indian hedgehog-regulated bone growth. Science 273, 663–666 (1996).

Hellemans, J. et al. Homozygous mutations in IHH cause acrocapitofemoral dysplasia, an autosomal recessive disorder with cone-shaped epiphyses in hands and hips. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 72, 1040–1046 (2003).

Vasques, G. A. et al. IHH gene mutations causing short stature with nonspecific skeletal abnormalities and response to growth hormone therapy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 103, 604–614 (2018).

Gleghorn, L., Ramesar, R., Beighton, P. & Wallis, G. A mutation in the variable repeat region of the aggrecan gene (AGC1) causes a form of spondyloepiphyseal dysplasia associated with severe, premature osteoarthritis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 77, 484–490 (2005).

Tompson, S. W. et al. A recessive skeletal dysplasia, SEMD aggrecan type, results from a missense mutation affecting the C-type lectin domain of aggrecan. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84, 72–79 (2009).

Domowicz, M. S., Cortes, M., Henry, J. G. & Schwartz, N. B. Aggrecan modulation of growth plate morphogenesis. Dev. Biol. 329, 242–257 (2009).

Laing, A. F., Lowell, S. & Brickman, J. M. Gro/TLE enables embryonic stem cell differentiation by repressing pluripotent gene expression. Dev. Biol. 397, 56–66 (2015).

Watanabe, H., Nakata, K., Kimata, K., Nakanishi, I. & Yamada, Y. Dwarfism and age-associated spinal degeneration of heterozygote cmd mice defective in aggrecan. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 94, 6943–6947 (1997).

Griffith, E. et al. Mutations in pericentrin cause Seckel syndrome with defective ATR-dependent DNA damage signaling. Nat. Genet. 40, 232–236 (2008).

Li, G. M. Mechanisms and functions of DNA mismatch repair. Cell Res. 18, 85–98 (2008).

Rauch, A. et al. Mutations in the pericentrin (PCNT) gene cause primordial dwarfism. Science 319, 816–819 (2008).

Farcy, S., Hachour, H., Bahi-Buisson, N. & Passemard, S. Genetic primary microcephalies: when centrosome dysfunction dictates brain and body size. Cells https://doi.org/10.3390/cells12131807 (2023).

Bond, J. et al. A centrosomal mechanism involving CDK5RAP2 and CENPJ controls brain size. Nat. Genet. 37, 353–355 (2005).

Al-Dosari, M. S., Shaheen, R., Colak, D. & Alkuraya, F. S. Novel CENPJ mutation causes Seckel syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 47, 411–414 (2010).

Guernsey, D. L. et al. Mutations in centrosomal protein CEP152 in primary microcephaly families linked to MCPH4. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87, 40–51 (2010).

Kalay, E. et al. CEP152 is a genome maintenance protein disrupted in Seckel syndrome. Nat. Genet. 43, 23–26 (2011).

Martin, C. A. et al. Mutations in PLK4, encoding a master regulator of centriole biogenesis, cause microcephaly, growth failure and retinopathy. Nat. Genet. 46, 1283–1292 (2014).

Makhdoom, E. U. H. et al. Modifier genes in microcephaly: a report on WDR62, CEP63, RAD50 and PCNT variants exacerbating disease caused by biallelic mutations of ASPM and CENPJ. Genes https://doi.org/10.3390/genes12050731 (2021).

Guernsey, D. L. et al. Mutations in origin recognition complex gene ORC4 cause Meier–Gorlin syndrome. Nat. Genet. 43, 360–364 (2011). Together with Bicknell et al. (2011, ref. 68) and Bicknell et al. (2011, ref. 69), these studies describe the first monogenic disorders related to DNA replication origin licensing causing a form of microcephalic primordial dwarfism, Meier–Gorlin syndrome.

Bicknell, L. S. et al. Mutations in the pre-replication complex cause Meier–Gorlin syndrome. Nat. Genet. 43, 356–359 (2011). Together with Guernsey et al. (2011) and Bicknell et al. (2011), these studies describe the first monogenic disorders related to DNA replication origin licensing causing a form of microcephalic primordial dwarfism, Meier–Gorlin syndrome.

Bicknell, L. S. et al. Mutations in ORC1, encoding the largest subunit of the origin recognition complex, cause microcephalic primordial dwarfism resembling Meier–Gorlin syndrome. Nat. Genet. 43, 350–355 (2011). Together with Guernsey et al. (2011) and Bicknell et al. (2011), these studies describe the first monogenic disorders related to DNA replication origin licensing causing a form of microcephalic primordial dwarfism, Meier–Gorlin syndrome.

Burrage, L. C. et al. De novo GMNN mutations cause autosomal-dominant primordial dwarfism associated with Meier–Gorlin syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 97, 904–913 (2015).

Fenwick, A. L. et al. Mutations in CDC45, encoding an essential component of the pre-initiation complex, cause Meier–Gorlin syndrome and craniosynostosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 99, 125–138 (2016).

Vetro, A. et al. MCM5: a new actor in the link between DNA replication and Meier–Gorlin syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 25, 646–650 (2017).

Knapp, K. M. et al. Linked-read genome sequencing identifies biallelic pathogenic variants in DONSON as a novel cause of Meier–Gorlin syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 57, 195–202 (2020).

Knapp, K. M. et al. MCM complex members MCM3 and MCM7 are associated with a phenotypic spectrum from Meier–Gorlin syndrome to lipodystrophy and adrenal insufficiency. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 29, 1110–1120 (2021).

Nabais Sa, M. J. et al. Biallelic GINS2 variant p.(Arg114Leu) causes Meier–Gorlin syndrome with craniosynostosis. J. Med. Genet. 59, 776–780 (2022).

McQuaid, M. E. et al. Hypomorphic GINS3 variants alter DNA replication and cause Meier–Gorlin syndrome. JCI Insight 7, e155648 (2022).

Nielsen-Dandoroff, E., Ruegg, M. S. G. & Bicknell, L. S. The expanding genetic and clinical landscape associated with Meier–Gorlin syndrome. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 31, 859–868 (2023).

Bongers, E. M. et al. Meier–Gorlin syndrome: report of eight additional cases and review. Am. J. Med. Genet. 102, 115–124 (2001).

Pachlopnik Schmid, J. et al. Polymerase epsilon1 mutation in a human syndrome with facial dysmorphism, immunodeficiency, livedo, and short stature (‘FILS syndrome’). J. Exp. Med. 209, 2323–2330 (2012).

Reynolds, J. J. et al. Mutations in DONSON disrupt replication fork stability and cause microcephalic dwarfism. Nat. Genet. 49, 537–549 (2017).

Cottineau, J. et al. Inherited GINS1 deficiency underlies growth retardation along with neutropenia and NK cell deficiency. J. Clin. Invest. 127, 1991–2006 (2017).

Mace, E. M. et al. Human NK cell deficiency as a result of biallelic mutations in MCM10. J. Clin. Invest. 130, 5272–5286 (2020).

Bellelli, R. & Boulton, S. J. Spotlight on the replisome: aetiology of DNA replication-associated genetic diseases. Trends Genet. 37, 317–336 (2021).

O’Driscoll, M., Ruiz-Perez, V. L., Woods, C. G., Jeggo, P. A. & Goodship, J. A. A splicing mutation affecting expression of ataxia–telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein (ATR) results in Seckel syndrome. Nat. Genet. 33, 497–501 (2003). This paper describes the first identification of a gene causing microcephalic primordial dwarfism, in this case, Seckel syndrome.

Ogi, T. et al. Identification of the first ATRIP-deficient patient and novel mutations in ATR define a clinical spectrum for ATR-ATRIP Seckel syndrome. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002945 (2012).

Tibelius, A. et al. Microcephalin and pericentrin regulate mitotic entry via centrosome-associated Chk1. J. Cell Biol. 185, 1149–1157 (2009).

Klingseisen, A. & Jackson, A. P. Mechanisms and pathways of growth failure in primordial dwarfism. Genes Dev. 25, 2011–2024 (2011).

Rao, E. et al. Pseudoautosomal deletions encompassing a novel homeobox gene cause growth failure in idiopathic short stature and Turner syndrome. Nat. Genet. 16, 54–63 (1997).

Montalbano, A. et al. Retinoic acid catabolizing enzyme CYP26C1 is a genetic modifier in SHOX deficiency. EMBO Mol. Med. 8, 1455–1469 (2016).

Hawkes, G. et al. Identification and analysis of individuals who deviate from their genetically-predicted phenotype. PLoS Genet. 19, e1010934 (2023).

Liang, J. S. et al. A newly recognised microdeletion syndrome of 2p15–16.1 manifesting moderate developmental delay, autistic behaviour, short stature, microcephaly, and dysmorphic features: a new patient with 3.2 Mb deletion. J. Med. Genet. 46, 645–647 (2009).

Coe, B. P. et al. Refining analyses of copy number variation identifies specific genes associated with developmental delay. Nat. Genet. 46, 1063–1071 (2014).

Barua, S. et al. 3q27.1 microdeletion causes prenatal and postnatal growth restriction and neurodevelopmental abnormalities. Mol. Cytogenet. 15, 7 (2022).

Wetzel, A. S. & Darbro, B. W. A comprehensive list of human microdeletion and microduplication syndromes. BMC Genom. Data 23, 82 (2022).

Ottesen, A. M. et al. Increased number of sex chromosomes affects height in a nonlinear fashion: a study of 305 patients with sex chromosome aneuploidy. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 152A, 1206–1212 (2010).

Dauber, A. et al. Genome-wide association of copy-number variation reveals an association between short stature and the presence of low-frequency genomic deletions. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 751–759 (2011).

Dietz, H. in GeneReviews® (eds Adam, M. P. et al.) (Univ. of Washington, Seattle, 1993).

Sedes, L. et al. Fibrillin-1 deficiency in the outer perichondrium causes longitudinal bone overgrowth in mice with Marfan syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 31, 3281–3289 (2022).

Pilia, G. et al. Mutations in GPC3, a glypican gene, cause the Simpson–Golabi–Behmel overgrowth syndrome. Nat. Genet. 12, 241–247 (1996).

Filmus, J., Capurro, M. & Rast, J. Glypicans. Genome Biol. 9, 224 (2008).

Cohen, A. S. et al. A novel mutation in EED associated with overgrowth. J. Hum. Genet. 60, 339–342 (2015).

Imagawa, E. et al. Mutations in genes encoding polycomb repressive complex 2 subunits cause Weaver syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 38, 637–648 (2017).

Drosos, Y. et al. NSD1 mediates antagonism between SWI/SNF and polycomb complexes and is required for transcriptional activation upon EZH2 inhibition. Mol. Cell 82, 2472–2489 e2478 (2022).

Kurotaki, N. et al. Haploinsufficiency of NSD1 causes Sotos syndrome. Nat. Genet. 30, 365–366 (2002).

Luscan, A. et al. Mutations in SETD2 cause a novel overgrowth condition. J. Med. Genet. 51, 512–517 (2014).

Chen, M. et al. Mutation pattern and genotype–phenotype correlations of SETD2 in neurodevelopmental disorders. Eur. J. Med. Genet. 64, 104200 (2021).

Kosho, T. et al. Clinical correlations of mutations affecting six components of the SWI/SNF complex: detailed description of 21 patients and a review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 161A, 1221–1237 (2013).

Malan, V. et al. Distinct effects of allelic NFIX mutations on nonsense-mediated mRNA decay engender either a Sotos-like or a Marshall–Smith syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 87, 189–198 (2010).

Bernier, R. et al. Disruptive CHD8 mutations define a subtype of autism early in development. Cell 158, 263–276 (2014).

Tatton-Brown, K. et al. Mutations in epigenetic regulation genes are a major cause of overgrowth with intellectual disability. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 100, 725–736 (2017).

Tatton-Brown, K. et al. Mutations in the DNA methyltransferase gene DNMT3A cause an overgrowth syndrome with intellectual disability. Nat. Genet. 46, 385–388 (2014).

Jeffries, A. R. et al. Growth disrupting mutations in epigenetic regulatory molecules are associated with abnormalities of epigenetic aging. Genome Res. 29, 1057–1066 (2019).

Bell-Hensley, A. et al. Skeletal abnormalities in mice with Dnmt3a missense mutations. Bone 183, 117085 (2024).

Smith, A. M. et al. Functional and epigenetic phenotypes of humans and mice with DNMT3A overgrowth syndrome. Nat. Commun. 12, 4549 (2021).

Russler-Germain, D. A. et al. The R882H DNMT3A mutation associated with AML dominantly inhibits wild-type DNMT3A by blocking its ability to form active tetramers. Cancer Cell 25, 442–454 (2014).

Lui, J. C. et al. Loss-of-function variant in SPIN4 causes an X-linked overgrowth syndrome. JCI Insight 8, e167074 (2023).

Hauer, N. N. et al. Clinical relevance of systematic phenotyping and exome sequencing in patients with short stature. Genet. Med. 20, 630–638 (2018).

Li, Q. et al. Molecular diagnostic yield of exome sequencing and chromosomal microarray in short stature: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 177, 1149–1157 (2023).

Visscher, P. M. et al. Assumption-free estimation of heritability from genome-wide identity-by-descent sharing between full siblings. PLoS Genet. 2, e41 (2006).

Campbell, H. & Rudan, I. Interpretation of genetic association studies in complex disease. Pharmacogenomics J. 2, 349–360 (2002).

Yang, J. et al. Genome partitioning of genetic variation for complex traits using common SNPs. Nat. Genet. 43, 519–525 (2011).

Pers, T. H. et al. Biological interpretation of genome-wide association studies using predicted gene functions. Nat. Commun. 6, 5890 (2015).

McCarthy, M. I. et al. Genome-wide association studies for complex traits: consensus, uncertainty and challenges. Nat. Rev. Genet. 9, 356–369 (2008).

Visscher, P. M. et al. 10 years of GWAS discovery: biology, function, and translation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 101, 5–22 (2017).

Hawkes, G. et al. Whole-genome sequencing in 333,100 individuals reveals rare non-coding single variant and aggregate associations with height. Nat. Commun. 15, 8549 (2024).

Lango Allen, H. et al. Hundreds of variants clustered in genomic loci and biological pathways affect human height. Nature 467, 832–838 (2010). This study was the first comprehensive genome-wide association study of height.

Marouli, E. et al. Rare and low-frequency coding variants alter human adult height. Nature 542, 186–190 (2017).

Lee, S. et al. Optimal unified approach for rare-variant association testing with application to small-sample case–control whole-exome sequencing studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 224–237 (2012).

Zuk, O. et al. Searching for missing heritability: designing rare variant association studies. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E455–E464 (2014).

Nicolae, D. L. Association tests for rare variants. Annu. Rev. Genom. Hum. Genet. 17, 117–130 (2016).

Backman, J. D. et al. Exome sequencing and analysis of 454,787 UK Biobank participants. Nature 599, 628–634 (2021).

Karczewski, K. J. et al. Systematic single-variant and gene-based association testing of thousands of phenotypes in 394,841 UK Biobank exomes. Cell Genom. 2, 100168 (2022).

Jurgens, S. J. et al. Analysis of rare genetic variation underlying cardiometabolic diseases and traits among 200,000 individuals in the UK Biobank. Nat. Genet. 54, 240–250 (2022).

Barton, A. R., Sherman, M. A., Mukamel, R. E. & Loh, P. R. Whole-exome imputation within UK Biobank powers rare coding variant association and fine-mapping analyses. Nat. Genet. 53, 1260–1269 (2021).

Kichaev, G. et al. Leveraging polygenic functional enrichment to improve GWAS power. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 104, 65–75 (2019).

Shi, S. et al. A Genomics England haplotype reference panel and imputation of UK Biobank. Nat. Genet. 56, 1800–1803 (2024).

Berndt, S. I. et al. Genome-wide meta-analysis identifies 11 new loci for anthropometric traits and provides insights into genetic architecture. Nat. Genet. 45, 501–512 (2013).

Estrada, K. et al. A genome-wide association study of northwestern Europeans involves the C-type natriuretic peptide signaling pathway in the etiology of human height variation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 3516–3524 (2009).

Gudbjartsson, D. F. et al. Many sequence variants affecting diversity of adult human height. Nat. Genet. 40, 609–615 (2008).

Dateki, S. ACAN mutations as a cause of familial short stature. Clin. Pediatr. Endocrinol. 26, 119–125 (2017).

Weedon, M. N. et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 20 loci that influence adult height. Nat. Genet. 40, 575–583 (2008).

Wood, A. R. et al. Defining the role of common variation in the genomic and biological architecture of adult human height. Nat. Genet. 46, 1173–1186 (2014).

Baronas, J. M. et al. Genome-wide CRISPR screening of chondrocyte maturation newly implicates genes in skeletal growth and height-associated GWAS loci. Cell Genom. 3, 100299 (2023).

Fukuzawa, R. et al. Autopsy case of microcephalic osteodysplastic primordial ‘dwarfism’ type II. Am. J. Med. Genet. 113, 93–96 (2002).

Sarig, O. et al. Short stature, onychodysplasia, facial dysmorphism, and hypotrichosis syndrome is caused by a POC1A mutation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 337–342 (2012).

Geister, K. A. et al. LINE-1 mediated insertion into Poc1a (Protein of Centriole 1A) causes growth insufficiency and male infertility in mice. PLoS Genet. 11, e1005569 (2015).

Marchini, A. et al. The short stature homeodomain protein SHOX induces cellular growth arrest and apoptosis and is expressed in human growth plate chondrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 37103–37114 (2004).

Lui, J. C. Growth disorders caused by variants in epigenetic regulators: progress and prospects. Front. Endocrinol. 15, 1327378 (2024).

Choufani, S. et al. DNA methylation signature for EZH2 functionally classifies sequence variants in three PRC2 complex genes. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 106, 596–610 (2020).

Hood, R. L. et al. The defining DNA methylation signature of Floating–Harbor syndrome. Sci. Rep. 6, 38803 (2016).

Mirzamohammadi, F. et al. Polycomb repressive complex 2 regulates skeletal growth by suppressing Wnt and TGF-β signalling. Nat. Commun. 7, 12047 (2016). An interesting paper that makes strong links between the developmental regulator polycomb repressive complex 2 and skeletal growth.

Lui, J. C. et al. EZH1 and EZH2 promote skeletal growth by repressing inhibitors of chondrocyte proliferation and hypertrophy. Nat. Commun. 7, 13685 (2016).

Benonisdottir, S. et al. Epigenetic and genetic components of height regulation. Nat. Commun. 7, 13490 (2016).

Zoledziewska, M. et al. Height-reducing variants and selection for short stature in Sardinia. Nat. Genet. 47, 1352–1356 (2015).

Sakai, L. Y., Keene, D. R., Renard, M. & De Backer, J. FBN1: the disease-causing gene for Marfan syndrome and other genetic disorders. Gene 591, 279–291 (2016).

Peeters, S., De Kinderen, P., Meester, J. A. N., Verstraeten, A. & Loeys, B. L. The fibrillinopathies: new insights with focus on the paradigm of opposing phenotypes for both FBN1 and FBN2. Hum. Mutat. 43, 815–831 (2022).

Ko, J. M. et al. Skeletal overgrowth syndrome caused by overexpression of C-type natriuretic peptide in a girl with balanced chromosomal translocation, t(1;2)(q41;q37.1). Am. J. Med. Genet. A 167A, 1033–1038 (2015).

Toydemir, R. M. et al. A novel mutation in FGFR3 causes camptodactyly, tall stature, and hearing loss (CATSHL) syndrome. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 79, 935–941 (2006).

Kake, T. et al. Chronically elevated plasma C-type natriuretic peptide level stimulates skeletal growth in transgenic mice. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 297, E1339–E1348 (2009).

Tsuji, T. & Kunieda, T. A loss-of-function mutation in natriuretic peptide receptor 2 (Npr2) gene is responsible for disproportionate dwarfism in cn/cn mouse. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 14288–14292 (2005).

Lorget, F. et al. Evaluation of the therapeutic potential of a CNP analog in a Fgfr3 mouse model recapitulating achondroplasia. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 91, 1108–1114 (2012).

Heyn, P. et al. Gain-of-function DNMT3A mutations cause microcephalic dwarfism and hypermethylation of polycomb-regulated regions. Nat. Genet. 51, 96–105 (2019).

Wu, H. et al. Dnmt3a-dependent nonpromoter DNA methylation facilitates transcription of neurogenic genes. Science 329, 444–448 (2010).

Franco, L. M. et al. A syndrome of short stature, microcephaly and speech delay is associated with duplications reciprocal to the common Sotos syndrome deletion. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 18, 258–261 (2010). An interesting case report illustrating how reciprocal structural genomic alterations can have the opposite effect on height.

Quintero-Rivera, F. et al. 5q35 duplication presents with psychiatric and undergrowth phenotypes mediated by NSD1 overexpression and mTOR signaling downregulation. Hum. Genet. 140, 681–690 (2021).

Estrada, K. et al. Identifying therapeutic drug targets using bidirectional effect genes. Nat. Commun. 12, 2224 (2021).

Fatumo, S. et al. A roadmap to increase diversity in genomic studies. Nat. Med. 28, 243–250 (2022).

Martin, A. R. et al. Increasing diversity in genomics requires investment in equitable partnerships and capacity building. Nat. Genet. 54, 740–745 (2022).

Carroll, S. R. et al. Using indigenous standards to implement the care principles: setting expectations through tribal research codes. Front. Genet. 13, 823309 (2022).

Carroll, S. R. et al. Extending the CARE principles from tribal research policies to benefit sharing in genomic research. Front. Genet. 13, 1052620 (2022).

Yasoda, A. et al. Systemic administration of C-type natriuretic peptide as a novel therapeutic strategy for skeletal dysplasias. Endocrinology 150, 3138–3144 (2009).

Weinberg, D. N. et al. Two competing mechanisms of DNMT3A recruitment regulate the dynamics of de novo DNA methylation at PRC1-targeted CpG islands. Nat. Genet. 53, 794–800 (2021).

Aref-Eshghi, E. et al. Evaluation of DNA methylation episignatures for diagnosis and phenotype correlations in 42 Mendelian neurodevelopmental disorders. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 108, 1161–1163 (2021).

Peeters, S. et al. DNA methylation profiling and genomic analysis in 20 children with short stature who were born small for gestational age. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. https://doi.org/10.1210/clinem/dgaa465 (2020).

To, K. et al. A multi-omic atlas of human embryonic skeletal development. Nature 635, 657–667 (2024).

Kelly, A. et al. Age-based reference ranges for annual height velocity in US children. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 99, 2104–2112 (2014).

Kornak, U. & Mundlos, S. Genetic disorders of the skeleton: a developmental approach. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 73, 447–474 (2003).

Hutchings, J. J., Escamilla, R. F., Deamer, W. C. & Li, C. H. Metabolic changes produced by human growth hormone (Li) in a pituitary dwarf. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 19, 759–769 (1959).

Raben, M. S. Treatment of a pituitary dwarf with human growth hormone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 18, 901–903 (1958).

Degenerative neurologic disease in patients formerly treated with human growth hormone: report of the committee on growth hormone use of the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society, May 1985. J. Pediatr. 107, 10–12 (1985).

Flodh, H. Human growth hormone produced with recombinant DNA technology: development and production. Acta Paediatr. Scand. Suppl. 325, 1–9 (1986).

Kucharska, A. et al. The effects of growth hormone treatment beyond growth promotion in patients with genetic syndromes: a systematic review of the literature. Int. J. Mol. Sci. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms251810169 (2024).

Savarirayan, R. et al. C-type natriuretic peptide analogue therapy in children with achondroplasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 381, 25–35 (2019). The first clinical trial reporting effects of C-type natriuretic peptide therapy in individuals with achondroplasia.

Savarirayan, R. et al. Once-daily, subcutaneous vosoritide therapy in children with achondroplasia: a randomised, double-blind, phase 3, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Lancet 396, 684–692 (2020).

Savarirayan, R. et al. Rationale, design, and methods of a randomized, controlled, open-label clinical trial with open-label extension to investigate the safety of vosoritide in infants, and young children with achondroplasia at risk of requiring cervicomedullary decompression surgery. Sci. Prog. 104, 368504211003782 (2021).

Savarirayan, R. et al. Safe and persistent growth-promoting effects of vosoritide in children with achondroplasia: 2-year results from an open-label, phase 3 extension study. Genet. Med. 23, 2443–2447 (2021).

Savarirayan, R. et al. Vosoritide therapy in children with achondroplasia aged 3–59 months: a multinational, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 8, 40–50 (2024).

Savarirayan, R. et al. Oral infigratinib therapy in children with achondroplasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 392, 865–874 (2025).

Savarirayan, R., Hoover-Fong, J., Yap, P. & Fredwall, S. O. New treatments for children with achondroplasia. Lancet Child. Adolesc. Health 8, 301–310 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank D. Aiylam, M. Babinksi, S. Vitale (Boston Children’s Hospital) and E. Nielsen Dandoroff (University of Otago) for assistance in compiling monogenic short and tall stature gene lists. J.N.H. is supported by NIH R01DK075787. R.S. is partly supported by NHMRC Leadership Fellow grant 2018081.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Genetics thanks Julian C. Lui; Ola Nilsson, who co-reviewed with Chrisanne Dsouza; and Gudrun Rappold for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Related links

ClinGen: https://clinicalgenome.org/

DECIPHER: https://www.deciphergenomics.org/

Genebass: https://app.genebass.org/

OMIM: https://omim.org/

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bicknell, L.S., Hirschhorn, J.N. & Savarirayan, R. The genetic basis of human height. Nat Rev Genet 26, 604–619 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-025-00834-1

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41576-025-00834-1

This article is cited by

-

GH1 gene polymorphism in Polish children and adolescents with short stature – reanalysis based on diverse growth hormone secretion

Endocrine (2026)

-

Autoimmune thyroid disease and pituitary adenoma in a female patient with 18p deletion syndrome: a case report and review of the literature

BMC Endocrine Disorders (2025)

-

Cellular and genetic mechanisms that shape the development and evolution of tail vertebral proportion in mice and jerboas

Nature Communications (2025)

-

Polymorphism of the HMGA2 gene in Polish children and adolescents with short stature and diverse growth hormone secretion

Journal of Applied Genetics (2025)