Abstract

Food allergy is an acute IgE-mediated reaction that occurs in response to food components and affects 1–10% of the global population. It is often thought to be a disease of the gastrointestinal tract, in which oral exposure to a food allergen induces an IgE-sensitizing response that primes the host immune system to react to the eliciting allergen following subsequent oral exposure. However, emerging evidence from clinical and basic research studies suggests that maladaptive immune responses in the skin also contribute to the development of food allergy. These responses can promote the development of food-specific IgE and reshape the gut immune microenvironment in a manner that predisposes to IgE-mediated activation of mast cells and clinical manifestations of allergic disease following subsequent food exposures. In this Review, we discuss how different routes of exposure to food antigens can contribute to allergic sensitization and describe how mast cells ultimately drive the allergic reaction to these food allergens.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Prausnitz, C. & Küstner, H. In Clinical Aspects of Immunology (eds Gell, P. G. H. & Coombs, R. R. A.) 808–816 (Blackwell, 1962).

Cohen, S. G. & Zelaya-Quesada, M. Prausnitz and Küstner phenomenon: the P-K reaction. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 114, 705–710 (2004).

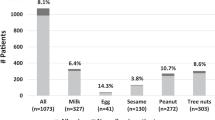

Ad hoc joint Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations/World Health Organization expert consultation on risk assessment of food allergens. Part 1: review and validation of Codex Alimentarius priority allergen list through risk assessment: meeting report (FAO/WHO, 2022).

Santos, A. F. et al. EAACI guidelines on the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy. Allergy 78, 3057–3076 (2023).

Hemmings, O. et al. Combining allergen components improves the accuracy of peanut allergy diagnosis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 10, 189–199 (2022).

Lieberman, J. A. et al. The utility of peanut components in the diagnosis of IgE-mediated peanut allergy among distinct populations. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 1, 75–82 (2013).

Zhuang, W. et al. The genome of cultivated peanut provides insight into legume karyotypes, polyploid evolution and crop domestication. Nat. Genet. 51, 865–876 (2019).

Bhat, R. S. et al. Genome-wide landscapes of genes and repeatome reveal the genomic differences between the two subspecies of peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Crop. Des. 2, 100029 (2023).

Breiteneder, H. & Mills, E. N. Molecular properties of food allergens. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 115, 14–23 (2005).

Shreffler, W. G. et al. The major glycoprotein allergen from Arachis hypogaea, Ara h 1, is a ligand of dendritic cell-specific ICAM-grabbing nonintegrin and acts as a Th2 adjuvant in vitro. J. Immunol. 177, 3677–3685 (2006).

Hill, D. A., Grundmeier, R. W., Ram, G. & Spergel, J. M. The epidemiologic characteristics of healthcare provider-diagnosed eczema, asthma, allergic rhinitis, and food allergy in children: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 16, 133 (2016).

Papapostolou, N., Xepapadaki, P., Gregoriou, S. & Makris, M. Atopic dermatitis and food allergy: a complex interplay what we know and what we would like to learn. J. Clin. Med. 11, 4232 (2022).

Mehta, Y. & Fulmali, D. G. Relationship between atopic dermatitis and food allergy in children. Cureus 14, e33160 (2022).

Strid, J., Hourihane, J., Kimber, I., Callard, R. & Strobel, S. Disruption of the stratum corneum allows potent epicutaneous immunization with protein antigens resulting in a dominant systemic Th2 response. Eur. J. Immunol. 34, 2100–2109 (2004).

Cerovic, V., Pabst, O. & Mowat, A. M. The renaissance of oral tolerance: merging tradition and new insights. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 25, 42–56 (2025). An in-depth summary of the key cellular and moleulcar processes that regulate oral tolerance.

Esterhazy, D. et al. Classical dendritic cells are required for dietary antigen-mediated induction of peripheral Treg cells and tolerance. Nat. Immunol. 17, 545–555 (2016). Describes the hierarchy of classical dendritic cell subsets in the induction of peripheral Treg cells and their redundancy during the development of oral tolerance.

Tordesillas, L. & Berin, M. C. Mechanisms of oral tolerance. Clin. Rev. Allergy Immunol. 55, 107–117 (2018).

Liu, E. G., Yin, X., Swaminathan, A. & Eisenbarth, S. C. Antigen-presenting cells in food tolerance and allergy. Front. Immunol. 11, 616020 (2020).

Schulz, O. et al. Intestinal CD103+, but not CX3CR1+, antigen sampling cells migrate in lymph and serve classical dendritic cell functions. J. Exp. Med. 206, 3101–3114 (2009).

Sun, T., Nguyen, A. & Gommerman, J. L. Dendritic cell subsets in intestinal immunity and inflammation. J. Immunol. 204, 1075–1083 (2020).

Husby, S., Mestecky, J., Moldoveanu, Z., Holland, S. & Elson, C. O. Oral tolerance in humans. T cell but not B cell tolerance after antigen feeding. J. Immunol. 152, 4663–4670 (1994).

Mowat, A. M. To respond or not to respond — a personal perspective of intestinal tolerance. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 18, 405–415 (2018).

Coombes, J. L. & Maloy, K. J. Control of intestinal homeostasis by regulatory T cells and dendritic cells. Semin. Immunol. 19, 116–126 (2007).

Sun, C. M. et al. Small intestine lamina propria dendritic cells promote de novo generation of Foxp3 T reg cells via retinoic acid. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1775–1785 (2007). The authors demonstrate that lamina propria dendritic cells promote Treg cell conversion dependent on TGFβ and retinoic acid.

Coombes, J. L. et al. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. J. Exp. Med. 204, 1757–1764 (2007).

Hong, S. W. et al. Immune tolerance of food is mediated by layers of CD4+ T cell dysfunction. Nature 607, 762–768 (2022). This study shows that exposure to food antigens causes cognate CD4+ naive T cells to form a complex set of non-canonical hyporesponsive T helper cell subsets that lack the inflammatory functions and have the potential to produce regulatory T cells.

Hadis, U. et al. Intestinal tolerance requires gut homing and expansion of FoxP3+ regulatory T cells in the lamina propria. Immunity 34, 237–246 (2011).

Stefka, A. T. et al. Commensal bacteria protect against food allergen sensitization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, 13145–13150 (2014).

Satitsuksanoa, P., Jansen, K., Globinska, A., van de Veen, W. & Akdis, M. Regulatory immune mechanisms in tolerance to food allergy. Front. Immunol. 9, 2939 (2018).

Lockhart, A. et al. Dietary protein shapes the profile and repertoire of intestinal CD4+ T cells. J. Exp. Med. 220, e20221816 (2023).

Barcik, W., Untersmayr, E., Pali-Scholl, I., O’Mahony, L. & Frei, R. Influence of microbiome and diet on immune responses in food allergy models. Drug Discov. Today Dis. Model. 17-18, 71–80 (2015).

Tan, J. et al. Dietary fiber and bacterial SCFA enhance oral tolerance and protect against food allergy through diverse cellular pathways. Cell Rep. 15, 2809–2824 (2016).

Tan, J. K., McKenzie, C., Mariño, E., Macia, L. & Mackay, C. R. Metabolite-sensing G protein-coupled receptors-facilitators of diet-related immune regulation. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 35, 371–402 (2017).

Underdown, B. J. & Schiff, J. M. Immunoglobulin A: strategic defense initiative at the mucosal surface. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 4, 389–417 (1986).

Brandtzaeg, P. et al. The human gastrointestinal secretory immune system in health and disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. Suppl. 114, 17–38 (1985).

Seikrit, C. & Pabst, O. The immune landscape of IgA induction in the gut. Semin. Immunopathol. 43, 627–637 (2021).

Hapfelmeier, S. et al. Reversible microbial colonization of germ-free mice reveals the dynamics of IgA immune responses. Science 328, 1705–1709 (2010).

Frehn, L. et al. Distinct patterns of IgG and IgA against food and microbial antigens in serum and feces of patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. PLoS ONE 9, e106750 (2014).

Zhang, B. et al. Divergent T follicular helper cell requirement for IgA and IgE production to peanut during allergic sensitization. Sci. Immunol. 5, eaay2754 (2020).

Sloper, K. S., Brook, C. G., Kingston, D., Pearson, J. R. & Shiner, M. Eczema and atopy in early childhood: low IgA plasma cell counts in the jejunal mucosa. Arch. Dis. Child. 56, 939–942 (1981).

Kukkonen, K. et al. High intestinal IgA associates with reduced risk of IgE-associated allergic diseases. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 21, 67–73 (2010).

Konstantinou, G. N. et al. Egg-white-specific IgA and IgA2 antibodies in egg-allergic children: is there a role in tolerance induction? Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 25, 64–70 (2014).

Wright, B. L. et al. Component-resolved analysis of IgA, IgE, and IgG4 during egg OIT identifies markers associated with sustained unresponsiveness. Allergy 71, 1552–1560 (2016).

Järvinen, K. M., Laine, S. T., Järvenpää, A. L. & Suomalainen, H. K. Does low IgA in human milk predispose the infant to development of cow’s milk allergy? Pediatr. Res. 48, 457–462 (2000).

Savilahti, E. et al. Low colostral IgA associated with cow’s milk allergy. Acta Paediatr. Scand. 80, 1207–1213 (1991).

Calbi, M. & Giacchetti, L. Low breast milk IgA and high blood eosinophil count in breast-fed newborns determine higher risk for developing atopic eczema after an 18-month follow-up. J. Investig. Allergol. Clin. Immunol. 8, 161–164 (1998).

Järvinen, K. M. et al. Role of maternal elimination diets and human milk IgA in the development of cow’s milk allergy in the infants. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 44, 69–78 (2014).

Savilahti, E., Siltanen, M., Kajosaari, M., Vaarala, O. & Saarinen, K. M. IgA antibodies, TGF-β1 and -β2, and soluble CD14 in the colostrum and development of atopy by age 4. Pediatr. Res. 58, 1300–1305 (2005).

Mosconi, E. et al. Breast milk immune complexes are potent inducers of oral tolerance in neonates and prevent asthma development. Mucosal Immunol. 3, 461–474 (2010).

Elesela, S. et al. Mucosal IgA immune complex induces immunomodulatory responses in allergic airway and intestinal TH2 disease. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 152, 1607–1618.e1601 (2023).

Liu, E. G. et al. Food-specific immunoglobulin A does not correlate with natural tolerance to peanut or egg allergens. Sci. Transl. Med. 14, eabq0599 (2022). This study showed that gut peanut-specific IgA does not predict protection from development of future peanut allergy in infants and calls into question the presumed protective role of food-specific IgA in food allergy.

Hoh, R. A. et al. Origins and clonal convergence of gastrointestinal IgE+ B cells in human peanut allergy. Sci. Immunol. 5, eaay4209 (2020).

Suárez-Fariñas, M. et al. Nonlesional atopic dermatitis skin is characterized by broad terminal differentiation defects and variable immune abnormalities. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127, 954–964.e951-954 (2011).

Tsakok, T. et al. Does atopic dermatitis cause food allergy? A systematic review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 137, 1071–1078 (2016).

Rogers, A. J., Celedón, J. C., Lasky-Su, J. A., Weiss, S. T. & Raby, B. A. Filaggrin mutations confer susceptibility to atopic dermatitis but not to asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120, 1332–1337 (2007).

Thyssen, J. P. et al. Filaggrin gene mutations are not associated with food and aeroallergen sensitization without concomitant atopic dermatitis in adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135, 1375–1378.e1371 (2015).

Irvine, A. D., McLean, W. H. I. & Leung, D. Y. M. Filaggrin mutations associated with skin and allergic diseases. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1315–1327 (2011).

Lack, G. Epidemiologic risks for food allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 121, 1331–1336 (2008). Description of the dual-allergen exposure hypothesis, proposing that oral antigen exposure leads to a tolerogenic response whereas environmental exposure to food antigens through an impaired skin barrier leads to allergic sensitization.

Strid, J., Hourihane, J., Kimber, I., Callard, R. & Strobel, S. Epicutaneous exposure to peanut protein prevents oral tolerance and enhances allergic sensitization. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 35, 757–766 (2005). Experimental evidence showing that epicutaneous exposure to peanut protein can prevent induction of oral tolerance.

Strid, J., Thomson, M., Hourihane, J., Kimber, I. & Strobel, S. A novel model of sensitization and oral tolerance to peanut protein. Immunology 113, 293–303 (2004).

Miller, S. D. & Hanson, D. G. Inhibition of specific immune responses by feeding protein antigens. IV. Evidence for tolerance and specific active suppression of cell-mediated immune responses to ovalbumin. J. Immunol. 123, 2344–2350 (1979).

van Halteren, A. G. et al. Regulation of antigen-specific IgE, IgG1, and mast cell responses to ingested allergen by mucosal tolerance induction. J. Immunol. 159, 3009–3015 (1997).

Menon, G. K. New insights into skin structure: scratching the surface. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 54 (Suppl. 1), S3–S17 (2002).

Zomer, H. D. & Trentin, A. G. Skin wound healing in humans and mice: challenges in translational research. J. Dermatol. Sci. 90, 3–12 (2018).

Du Toit, G. et al. Randomized trial of peanut consumption in infants at risk for peanut allergy. N. Engl. J. Med. 372, 803–813 (2015). Critical clinical study showing that early oral introduction of peanut decreases the risk of developing peanut allergy among high-risk children.

Brough, H. A. et al. Atopic dermatitis increases the effect of exposure to peanut antigen in dust on peanut sensitization and likely peanut allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 135, 164–170 (2015). Important clinical evidence that early environmental peanut exposure increases the risk of peanut sensitization and allergy in young atopic children and this effect is augmented in children with a history of atopic dermatitis.

Johansen, P., von Moos, S., Mohanan, D., Kündig, T. M. & Senti, G. New routes for allergen immunotherapy. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 8, 1525–1533 (2012).

Hervé, P. L. et al. Recent advances in epicutaneous immunotherapy and potential applications in food allergy. Front. Allergy 4, 1290003 (2023).

Vallery-Radot, P. & Hangenau, J. Asthme d’origine équine. Essai de désensibilisation par des cutiréactions répétées. Bull. Soc. Méd. H.ôp. Paris 45, 1251–1260 (1921).

Pautrizel, R., Cabanieu, G., Bricaud, H. & Broustet, P. [Allergenic group specificity & therapeutic consequences in asthma; specific desensitization method by epicutaneous route]. Sem. Hop. 33, 1394–1403 (1957).

Blamoutier, P., Blamoutier, J. & Guibert, L. [Treatment of pollinosis with pollen extracts by the method of cutaneous quadrille ruling]. Presse Med. 67, 2299–2301 (1959).

Senti, G., von Moos, S. & Kündig, T. M. Epicutaneous immunotherapy for aeroallergen and food allergy. Curr. Treat. Options Allergy 1, 68–78 (2014).

Mondoulet, L., Dioszeghy, V., Thébault, C., Benhamou, P. H. & Dupont, C. Epicutaneous immunotherapy for food allergy as a novel pathway for oral tolerance induction. Immunotherapy 7, 1293–1305 (2015).

Fallon, P. G. et al. A homozygous frameshift mutation in the mouse Flg gene facilitates enhanced percutaneous allergen priming. Nat. Genet. 41, 602–608 (2009). Key experimental evidence showing that antigen transfer through a defective epidermal barrier is a key mechanism underlying increased IgE sensitization.

Moniaga, C. S. & Kabashima, K. Filaggrin in atopic dermatitis: flaky tail mice as a novel model for developing drug targets in atopic dermatitis. Inflamm. Allergy Drug Targets 10, 477–485 (2011).

Moniaga, C. S. et al. Flaky tail mouse denotes human atopic dermatitis in the steady state and by topical application with Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus extract. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 2385–2393 (2010).

Oyoshi, M. K., Murphy, G. F. & Geha, R. S. Filaggrin-deficient mice exhibit TH17-dominated skin inflammation and permissiveness to epicutaneous sensitization with protein antigen. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 124, 485–493, 493 e481 (2009).

Scharschmidt, T. C. et al. Filaggrin deficiency confers a paracellular barrier abnormality that reduces inflammatory thresholds to irritants and haptens. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 124, 496–506, 506.e1-6 (2009).

Kezic, S. et al. Filaggrin loss-of-function mutations are associated with enhanced expression of IL-1 cytokines in the stratum corneum of patients with atopic dermatitis and in a murine model of filaggrin deficiency. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129, 1031–1039.e1031 (2012).

Nakai, K. et al. Reduced expression of epidermal growth factor receptor, E-cadherin, and occludin in the skin of flaky tail mice is due to filaggrin and loricrin deficiencies. Am. J. Pathol. 181, 969–977 (2012).

Schülke, S. & Albrecht, M. Mouse models for food allergies: where do we stand? Cells 8, 546 (2019).

Kanagaratham, C., Sallis, B. F. & Fiebiger, E. Experimental models for studying food allergy. Cell. Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 356–369.e351 (2018). Summary of the strengths and weaknesses of mouse models of food allergy.

Graham, M. T. & Nadeau, K. C. Lessons learned from mice and man: mimicking human allergy through mouse models. Clin. Immunol. 155, 1–16 (2014).

Searle, A. G. & Spearman, R. I. ‘Matted’, a new hair-mutant in the house-mouse: genetics and morphology. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol. 5, 93–102 (1957).

Lane, P. W. Two new mutations in linkage group XVI of the house mouse. Flaky tail varitint-waddler-J. J. Hered. 63, 135–140 (1972).

Palmer, C. N. et al. Common loss-of-function variants of the epidermal barrier protein filaggrin are a major predisposing factor for atopic dermatitis. Nat. Genet. 38, 441–446 (2006).

Sandilands, A. et al. Comprehensive analysis of the gene encoding filaggrin uncovers prevalent and rare mutations in ichthyosis vulgaris and atopic eczema. Nat. Genet. 39, 650–654 (2007).

Saunders, S. P. et al. Tmem79/Matt is the matted mouse gene and is a predisposing gene for atopic dermatitis in human subjects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 132, 1121–1129 (2013).

Presland, R. B. et al. Loss of normal profilaggrin and filaggrin in flaky tail (ft/ft) mice: an animal model for the filaggrin-deficient skin disease ichthyosis vulgaris. J. Invest. Dermatol. 115, 1072–1081 (2000).

Sasaki, T. et al. A homozygous nonsense mutation in the gene for Tmem79, a component for the lamellar granule secretory system, produces spontaneous eczema in an experimental model of atopic dermatitis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 132, 1111–1120.e1114 (2013).

Egawa, G. & Kabashima, K. Multifactorial skin barrier deficiency and atopic dermatitis: essential topics to prevent the atopic march. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 138, 350–358.e351 (2016).

Saunders, S. P. et al. Spontaneous atopic dermatitis is mediated by innate immunity, with the secondary lung inflammation of the atopic march requiring adaptive immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 137, 482–491 (2016).

Tominaga, M. & Takamori, K. Peripheral itch sensitization in atopic dermatitis. Allergol. Int. 71, 265–277 (2022).

Ebina-Shibuya, R. & Leonard, W. J. Role of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in allergy and beyond. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 23, 24–37 (2023).

Hasegawa, T., Oka, T. & Demehri, S. Alarmin cytokines as central regulators of cutaneous immunity. Front. Immunol. 13, 876515 (2022).

Galand, C. et al. IL-33 promotes food anaphylaxis in epicutaneously sensitized mice by targeting mast cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 138, 1356–1366 (2016).

Oyoshi, M. K., Larson, R. P., Ziegler, S. F. & Geha, R. S. Mechanical injury polarizes skin dendritic cells to elicit a TH2 response by inducing cutaneous thymic stromal lymphopoietin expression. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 126, 976–984, 984 e971-975 (2010).

Leyva-Castillo, J. M., Hener, P., Jiang, H. & Li, M. TSLP produced by keratinocytes promotes allergen sensitization through skin and thereby triggers atopic march in mice. J. Invest. Dermatol. 133, 154–163 (2013).

Bartnikas, L. M. et al. Epicutaneous sensitization results in IgE-dependent intestinal mast cell expansion and food-induced anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 131, 451–460 e451-456 (2013). Experimental evidence showing that mechanical skin injury in the presence of food antigen was sufficient to induce sensitizing TH2 cell and IgE responses in the skin and predispose to food allergy.

Brandt, E. B. et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin rather than IL-33 drives food allergy after epicutaneous sensitization to food allergen. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 151, 1660–1666.e1664 (2023).

Seo, S. H., Kim, S., Kim, S. E., Chung, S. & Lee, S. E. Enhanced thermal sensitivity of TRPV3 in keratinocytes underlies heat-induced pruritogen release and pruritus in atopic dermatitis. J. Invest. Dermatol. 140, 2199–2209.e2196 (2020).

Vu, A. T. et al. Extracellular double-stranded RNA induces TSLP via an endosomal acidification- and NF-κB-dependent pathway in human keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 131, 2205–2212 (2011).

Moniaga, C. S. et al. Protease activity enhances production of thymic stromal lymphopoietin and basophil accumulation in flaky tail mice. Am. J. Pathol. 182, 841–851 (2013).

Brough, H. A. et al. Epicutaneous sensitization in the development of food allergy: what is the evidence and how can this be prevented? Allergy 75, 2185–2205 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Exploring the role of Staphylococcus aureus in inflammatory diseases. Toxins 14, 464 (2022).

Saloga, J. et al. Inhibition of the development of immediate hypersensitivity by staphylococcal enterotoxin B. Eur. J. Immunol. 24, 3140–3147 (1994).

Ganeshan, K. et al. Impairing oral tolerance promotes allergy and anaphylaxis: a new murine food allergy model. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 123, 231–238.e234 (2009).

Savinko, T. et al. Topical superantigen exposure induces epidermal accumulation of CD8+ T cells, a mixed Th1/Th2-type dermatitis and vigorous production of IgE antibodies in the murine model of atopic dermatitis. J. Immunol. 175, 8320–8326 (2005).

Forbes-Blom, E., Camberis, M., Prout, M., Tang, S. C. & Le Gros, G. Staphylococcal-derived superantigen enhances peanut induced Th2 responses in the skin. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 42, 305–314 (2012).

Ito, T. et al. TSLP-activated dendritic cells induce an inflammatory T helper type 2 cell response through OX40 ligand. J. Exp. Med. 202, 1213–1223 (2005). Experimental evidence showing that TSLP also promotes the differentiation of naive CD4+ T cells into TH2 cells via induction of OX40L on dendritic cell populations.

Rochman, I., Watanabe, N., Arima, K., Liu, Y. J. & Leonard, W. J. Cutting edge: direct action of thymic stromal lymphopoietin on activated human CD4+ T cells. J. Immunol. 178, 6720–6724 (2007).

Omori, M. & Ziegler, S. Induction of IL-4 expression in CD4+ T cells by thymic stromal lymphopoietin. J. Immunol. 178, 1396–1404 (2007).

Ochiai, S. et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin drives the development of IL-13+ Th2 cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115, 1033–1038 (2018).

Pattarini, L. et al. TSLP-activated dendritic cells induce human T follicular helper cell differentiation through OX40-ligand. J. Exp. Med. 214, 1529–1546 (2017).

Noti, M. et al. Exposure to food allergens through inflamed skin promotes intestinal food allergy through the thymic stromal lymphopoietin–basophil axis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 133, 1390–1399 (2014). The authors show that epicutaneous sensitization on a disrupted skin barrier is associated with accumulation of TSLP-elicited basophils, which are required for intestinal food allergy.

Leyva-Castillo, J. M. et al. IL-4 acts on skin-derived dendritic cells to promote the TH2 response to cutaneous sensitization and the development of allergic skin inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 154, 1462–1471.e3 (2024).

Noah, T. K. et al. IL-13-induced Intestinal secretory epithelial cell antigen passages are required for IgE-mediated food-induced anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 144, 1058–1073.e3 (2019). Demonstration that SAPs channel food antigens across the small intestine epithelium and regulate the onset of food allergic reactions.

Lee, J. B. et al. IL-25 and CD4+ TH2 cells enhance type 2 innate lymphoid cell-derived IL-13 production, which promotes IgE-mediated experimental food allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 137, 1216–1225 e1215 (2016).

Ahrens, R. et al. Intestinal mast cell levels control severity of oral antigen-induced anaphylaxis in mice. Am. J. Pathol. 180, 1535–1546 (2012).

Forbes, E. E. et al. IL-9- and mast cell-mediated intestinal permeability predisposes to oral antigen hypersensitivity. J. Exp. Med. 205, 897–913 (2008). Demonstration of the important role for increased mast cell numbers in the gut in food allergy.

Dokoshi, T. et al. Dermal injury drives a skin to gut axis that disrupts the intestinal microbiome and intestinal immune homeostasis in mice. Nat. Commun. 15, 3009 (2024).

Leyva-Castillo, J. M. et al. Mechanical skin injury promotes food anaphylaxis by driving intestinal mast cell expansion. Immunology 50, 1262–1275.e1264 (2019). Experimental demonstration that skin-derived IL-33 alters the gut immune environment driving intestinal mast cell expansion and predisposes to food allergy.

Schwartz, L. B., Metcalfe, D. D., Miller, J. S., Earl, H. & Sullivan, T. Tryptase levels as an indicator of mast-cell activation in systemic anaphylaxis and mastocytosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 316, 1622–1626 (1987).

Francis, A. et al. Neutrophil activation during acute human anaphylaxis: analysis of MPO and sCD62L. Clin. Exp. Allergy 47, 361–370 (2017).

Stone, S. F. et al. Elevated serum cytokines during human anaphylaxis: identification of potential mediators of acute allergic reactions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 124, 786–792 e784 (2009).

Kaliner, M., Sigler, R., Summers, R. & Shelhamer, J. H. Effects of infused histamine: analysis of the effects of H-1 and H-2 histamine receptor antagonists on cardiovascular and pulmonary responses. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 68, 365–371 (1981).

Vigorito, C. et al. Cardiovascular effects of histamine infusion in man. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 5, 531–537 (1983).

Sampson, H. A. & Jolie, P. L. Increased plasma histamine concentrations after food challenges in children with atopic dermatitis. N. Engl. J. Med. 311, 372–376 (1984). First evidence of increased plasma histamine concentrations during a food allergic reaction.

Reimann, H. J., Ring, J., Ultsch, B. & Wendt, P. Intragastral provocation under endoscopic control (IPEC) in food allergy: mast cell and histamine changes in gastric mucosa. Clin. Allergy 15, 195–202 (1985).

Lin, R. Y. et al. Histamine and tryptase levels in patients with acute allergic reactions: an emergency department-based study. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 106, 65–71 (2000).

Sampson, H. A., Mendelson, L. & Rosen, J. P. Fatal and near-fatal anaphylactic reactions to food in children and adolescents. N. Engl. J. Med. 327, 380–384 (1992).

Ohtsuka, T. et al. Time course of plasma histamine and tryptase following food challenges in children with suspected food allergy. Ann. Allergy 71, 139–146 (1993).

Vadas, P., Perelman, B. & Liss, G. Platelet-activating factor, histamine, and tryptase levels in human anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 131, 144–149 (2013).

Santos, A. F. et al. Basophil activation test discriminates between allergy and tolerance in peanut-sensitized children. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 134, 645–652 (2014).

Bergmann, M. M. & Santos, A. F. Basophil activation test in the food allergy clinic: its current use and future applications. Expert Rev. Clin. Immunol. 20, 1297–1304 (2024).

Savage, J. H. et al. Kinetics of mast cell, basophil, and oral food challenge responses in omalizumab-treated adults with peanut allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 130, 1123–1129.e1122 (2012).

Hussain, M. et al. Basophil-derived IL-4 promotes epicutaneous antigen sensitization concomitant with the development of food allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 141, 223–234.e225 (2018).

Muto, T. et al. The role of basophils and proallergic cytokines, TSLP and IL-33, in cutaneously sensitized food allergy. Int. Immunol. 26, 539–549 (2014).

Kashiwakura, J. I. et al. The basophil–IL-4–mast cell axis is required for food allergy. Allergy 74, 1992–1996 (2019).

Reber, L. L. et al. Selective ablation of mast cells or basophils reduces peanut-induced anaphylaxis in mice. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 132, 881–888.e881-811 (2013).

Arias, K. et al. Distinct immune effector pathways contribute to the full expression of peanut-induced anaphylactic reactions in mice. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 127, 1552–1561.e1551 (2011).

Smit, J. J. et al. Contribution of classic and alternative effector pathways in peanut-induced anaphylactic responses. PLoS ONE 6, e28917 (2011).

Finkelman, F. D., Khodoun, M. V. & Strait, R. Human IgE-independent systemic anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 137, 1674–1680 (2016).

Brandt, E. B. et al. Mast cells are required for experimental oral allergen-induced diarrhea. J. Clin. Invest. 112, 1666–1677 (2003).

Kucuk, Z. Y. et al. Induction and suppression of allergic diarrhea and systemic anaphylaxis in a murine model of food allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 129, 1343–1348 (2012).

Dua, S. et al. Diagnostic value of tryptase in food allergic reactions: a prospective study of 160 adult peanut challenges. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 6, 1692–1698.e1691 (2018).

Osterfeld, H. et al. Differential roles for the IL-9/IL-9 receptor alpha-chain pathway in systemic and oral antigen-induced anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125, 469–476 e462 (2010).

Ptaschinski, C., Rasky, A. J., Fonseca, W. & Lukacs, N. W. Stem cell factor neutralization protects from severe anaphylaxis in a murine model of food allergy. Front. Immunol. 12, 604192 (2021).

Boyce, J. A. et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of food allergy in the united states: summary of the NIAID-sponsored expert panel report. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 126, 1105–1118 (2010).

Silverman, H. J., Van Hook, C. & Haponik, E. F. Hemodynamic changes in human anaphylaxis. Am. J. Med. 77, 341–344 (1984).

Brown, S. G. The pathophysiology of shock in anaphylaxis. Immunol. Allergy Clin. North Am. 27, 165–175 (2007).

Fisher, M. M. Clinical observations on the pathophysiology and treatment of anaphylactic cardiovascular collapse. Anaesth. Intensive Care 14, 17–21 (1986). This study established hypovolemia as a primary mechanism of cardiovascular collapse in severe anaphylaxis.

Beaupre, P. N. et al. Intraoperative detection of changes in left ventricular segmental wall motion by transesophageal two-dimensional echocardiography. Am. Heart J. 107, 1021–1023 (1984).

Fisher, M. Blood volume replacement in acute anaphylactic cardiovascular collapse related to anaesthesia. Br. J. Anaesth. 49, 1023–1026 (1977).

Turner, P. J. et al. Can we identify patients at risk of life-threatening allergic reactions to food? Allergy 71, 1241–1255 (2016).

Turner, P. J. & Campbell, D. E. Epidemiology of severe anaphylaxis: can we use population-based data to understand anaphylaxis? Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 16, 441–450 (2016).

Ruiz-Garcia, M. et al. Cardiovascular changes during peanut-induced allergic reactions in human subjects. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 147, 633–642 (2021). Demonstration that significant cardiovascular changes in mild and more severe peanut-induced reactions.

Fineman, S. M. Optimal treatment of anaphylaxis: antihistamines versus epinephrine. Postgrad. Med. 126, 73–81 (2014).

Whyte, A. F. et al. Emergency treatment of anaphylaxis: concise clinical guidance. Clin. Med. 22, 332–339 (2022).

Wang, J. & Sampson, H. A. Food anaphylaxis. Clin. Exp. Allergy 37, 651–660 (2007).

Munoz, J. & Bergman, R. K. Mechanism of anaphylactic death in the mouse. Nature 205, 199–200 (1965).

Bergmann, R. K. & Munoz, J. Circulatory chnages in anaphylaxis and histamine toxicity in mice. J. Immunol. 95, 1–8 (1965).

Strait, R. T., Morris, S. C., Smiley, K., Urban, J. F. Jr. & Finkelman, F. D. IL-4 exacerbates anaphylaxis. J. Immunol. 170, 3835–3842 (2003). First demonstration that IL-4 can enhance the IgE- and histamine-mediated increase in shock.

Wechsler, J. B., Schroeder, H. A., Byrne, A. J., Chien, K. B. & Bryce, P. J. Anaphylactic responses to histamine in mice utilize both histamine receptors 1 and 2. Allergy 68, 1338–1340 (2013).

Makabe-Kobayashi, Y. et al. The control effect of histamine on body temperature and respiratory function in IgE-dependent systemic anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 110, 298–303 (2002).

Finkelman, F. D. Anaphylaxis: lessons from mouse models. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 120, 506–515 (2007).

Morris, S. C. et al. Optimizing drug inhibition of IgE-mediated anaphylaxis in mice. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 149, 671–684.e679 (2022).

Andriopoulou, P., Navarro, P., Zanetti, A., Lampugnani, M. G. & Dejana, E. Histamine induces tyrosine phosphorylation of endothelial cell-to-cell adherens junctions. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 19, 2286–2297 (1999).

Hox, V. et al. Diminution of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 signaling inhibits vascular permeability and anaphylaxis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 138, 187–199 (2016).

Chislock, E. M. & Pendergast, A. M. Abl family kinases regulate endothelial barrier function in vitro and in mice. PLoS ONE 8, e85231 (2013).

Mikelis, C. M. et al. RhoA and ROCK mediate histamine-induced vascular leakage and anaphylactic shock. Nat. Commun. 6, 6725 (2015).

Wallez, Y. et al. Src kinase phosphorylates vascular endothelial-cadherin in response to vascular endothelial growth factor: identification of tyrosine 685 as the unique target site. Oncogene 26, 1067–1077 (2007).

Weis, S., Cui, J., Barnes, L. & Cheresh, D. Endothelial barrier disruption by VEGF-mediated Src activity potentiates tumor cell extravasation and metastasis. J. Cell Biol. 167, 223–229 (2004).

Deo, D. D., Bazan, N. G. & Hunt, J. D. Activation of platelet-activating factor receptor-coupled Gαq leads to stimulation of Src and focal adhesion kinase via two separate pathways in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 3497–3508 (2004).

Strait, R., Morrist, S. C. & Finkelman, F. D. Cytokine enhancement of anaphylaxis. Novartis Found. Symp. 257, 80–91, discussion 91–100, 276–185 (2004).

Yamani, A. et al. The vascular endothelial specific IL-4 receptor alpha-ABL1 kinase signaling axis regulates the severity of IgE-mediated anaphylactic reactions. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 142, 1159–1172.e1155 (2018). Shows that IL-4 exacerbation of histamine-induced shock in mice was dependent on vascular endothelial expression of IL-4Rα.

Krempski, J. et al. IL-4-STAT6 axis amplifies histamine-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction and hypovolemic shock. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 154, 719–734 (2024). Shows that IL-4 can amplify histamine-induced vascular ednothelial dysfunction via active de novo protein synthesis and transcriptional activity via STAT6-dependent signaling pathways.

Bao, C. et al. A mast cell–thermoregulatory neuron circuit axis regulates hypothermia in anaphylaxis. Sci. Immunol. 8, eadc9417 (2023). Shows that IgE-mediated activation of mast cells can also lead to the activation of a thermoregulatory neural circuit that contributes to the transient hypothermic response.

Randhawa, P. K. & Jaggi, A. S. TRPV1 channels in cardiovascular system: a double edged sword? Int. J. Cardiol. 228, 103–113 (2017).

Brandt, E. B. et al. Oral antigen-induced intestinal anaphylaxis requires IgE-dependent mast cell degranulation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 111, S339 (2003).

Yamani, A. et al. Dysregulation of intestinal epithelial CFTR-dependent Cl− ion transport and paracellular barrier function drives gastrointestinal symptoms of food-induced anaphylaxis in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 14, 135–143 (2021).

Perdue, M. H., Masson, S., Wershil, B. K. & Galli, S. J. Role of mast cells in ion transport abnormalities associated with intestinal anaphylaxis. Correction of the diminished secretory response in genetically mast cell-deficient W/Wv mice by bone marrow transplantation. J. Clin. Invest. 87, 687–693 (1991).

Crowe, S. E., Sestini, P. & Perdue, M. H. Allergic reactions of rat jejunal mucosa. Ion transport responses to luminal antigen and inflammatory mediators. Gastroenterology 99, 74–82 (1990).

Kellum, J. M., Wu, J. & Donowitz, M. Enteric neural pathways inhibitory to rabbit duodenal serotonin release. Surgery 96, 139–145 (1984).

Collins, D., Hogan, A. M., Skelly, M. M., Baird, A. W. & Winter, D. C. Cyclic AMP-mediated chloride secretion is induced by prostaglandin F2α in human isolated colon. Br. J. Pharmacol. 158, 1771–1776 (2009).

Mourad, F. H., O’Donnell, L. J., Ogutu, E., Dias, J. A. & Farthing, M. J. Role of 5-hydroxytryptamine in intestinal water and electrolyte movement during gut anaphylaxis. Gut 36, 553–557 (1995).

Ooe, M., Asano, K., Haga, K. & Setoguchi, M. [Effect of Y-25130, a selective 5-HT3 receptor antagonist, on the intestinal fluid secretion in rats].Nihon Yakurigaku Zasshi 101, 299–307 (1993).

Mroz, M. S. et al. Farnesoid X receptor agonists attenuate colonic epithelial secretory function and prevent experimental diarrhoea in vivo. Gut 63, 808–817 (2014).

Turner, M. W. et al. Intestinal hypersensitivity reactions in the rat. I. Uptake of intact protein, permeability to sugars and their correlation with mucosal mast-cell activation. Immunology 63, 119–124 (1988).

King, S. J., Miller, H. R., Newlands, G. F. & Woodbury, R. G. Depletion of mucosal mast cell protease by corticosteroids: effect on intestinal anaphylaxis in the rat. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 82, 1214–1218 (1985).

Scudamore, C. L., Thornton, E. M., McMillan, L., Newlands, G. F. & Miller, H. R. Release of the mucosal mast cell granule chymase, rat mast cell protease-II, during anaphylaxis is associated with the rapid development of paracellular permeability to macromolecules in rat jejunum. J. Exp. Med. 182, 1871–1881 (1995).

Groschwitz, K. R. & Hogan, S. P. Intestinal barrier function: molecular regulation and disease pathogenesis. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 124, 3–20 (2009). Review summarizing the role of intestinal epithelial barrier in disease susceptability.

Turner, J. R. Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 9, 799–809 (2009).

Pejler, G., Abrink, M., Ringvall, M. & Wernersson, S. Mast cell proteases. Adv. Immunol. 95, 167–255 (2007).

Bankova, L. G. et al. Mouse mast cell proteases 4 and 5 mediate epidermal injury through disruption of tight junctions. J. Immunol. 192, 2812–2820 (2014).

Lawrence, C. E., Paterson, Y. Y., Wright, S. H., Knight, P. A. & Miller, H. R. Mouse mast cell protease-1 is required for the enteropathy induced by gastrointestinal helminth infection in the mouse. Gastroenterology 127, 155–165 (2004).

Groschwitz, K. R. et al. Mast cells regulate homeostatic intestinal epithelial migration and barrier function by a chymase/Mcpt4-dependent mechanism. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 22381–22386 (2009).

Groschwitz, K. R., Wu, D., Osterfeld, H., Ahrens, R. & Hogan, S. P. Chymase-mediated intestinal epithelial permeability is regulated by a protease-activating receptor/matrix metalloproteinase-2-dependent mechanism. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 304, G479–G489 (2013).

Jacob, C. et al. Mast cell tryptase controls paracellular permeability of the intestine. Role of protease-activated receptor 2 and beta-arrestins. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 31936–31948 (2005).

Wilcz-Villega, E. M., McClean, S. & O’Sullivan, M. A. Mast cell tryptase reduces junctional adhesion molecule-A (JAM-A) expression in intestinal epithelial cells: implications for the mechanisms of barrier dysfunction in irritable bowel syndrome. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 108, 1140–1151 (2013).

Scudamore, C. L. et al. Basal secretion and anaphylactic release of rat mast cell protease-II (RMCP-II) from ex vivo perfused rat jejunum: translocation of RMCP-II into the gut lumen and its relation to mucosal histology. Gut 37, 235–241 (1995).

Iding, J. et al. Standardized quantification of mast cells in the gastrointestinal tract in adults. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 12, 472–481 (2024).

Tison, B. E. et al. Number and distribution of mast cells in the pediatric gastrointestinal tract. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 125, AB182 (2010).

Arinobu, Y. et al. Developmental checkpoints of the basophil/mast cell lineages in adult murine hematopoiesis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. Usa. 102, 18105–18110 (2005).

Hallgren, J. & Gurish, M. F. Mast cell progenitor trafficking and maturation. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 716, 14–28 (2011).

Gurish, M. F. & Boyce, J. A. Mast cells: ontogeny, homing, and recruitment of a unique innate effector cell. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 117, 1285–1291 (2006).

Bankova, L. G., Dwyer, D. F., Liu, A. Y., Austen, K. F. & Gurish, M. F. Maturation of mast cell progenitors to mucosal mast cells during allergic pulmonary inflammation in mice. Mucosal Immunol. 8, 596–606 (2015).

Gurish, M. F. et al. Intestinal mast cell progenitors require CD49dβ7 (α4β7 integrin) for tissue-specific homing. J. Exp. Med. 194, 1243–1252 (2001).

Abonia, J. P. et al. Constitutive homing of mast cell progenitors to the intestine depends on autologous expression of the chemokine receptor CXCR2. Blood 105, 4308–4313 (2005).

Pennock, J. L. & Grencis, R. K. The mast cell and gut nematodes: damage and defence. Chem. Immunol. Allergy 90, 128–140 (2006).

St John, A. L., Rathore, A. P. S. & Ginhoux, F. New perspectives on the origins and heterogeneity of mast cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 23, 55–68 (2023).

Gurish, M. F. & Austen, K. F. The diverse role of mast cells. J. Exp. Med. 194, 1–5 (2001).

Reimann, H. J. & Lewin, J. Gastric mucosal reactions in patients with food allergy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 83, 1212–1219 (1988).

Bengtsson, U. et al. IgE-positive duodenal mast cells in patients with food-related diarrhea. Int. Arch. Allergy Appl. Immunol. 95, 86–91 (1991).

Li, Y., Qi, X., Zhao, D., Urban, J. F. & Huang, H. IL-3 expands pre-basophil and mast cell progenitors by upregulating the IL-3 receptor expression. Cell. Immunol. 374, 104498 (2022).

Bischoff, S. C., Sellge, G., Schwengberg, S., Lorentz, A. & Manns, M. P. Stem cell factor-dependent survival, proliferation and enhanced releasability of purified mature mast cells isolated from human intestinal tissue. Int. Arch. Allergy Immunol. 118, 104–107 (1999).

Bischoff, S. C. et al. IL-4 enhances proliferation and mediator release in mature human mast cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 8080–8085 (1999).

Pajulas, A. et al. Interleukin-9 promotes mast cell progenitor proliferation and CCR2-dependent mast cell migration in allergic airway inflammation. Mucosal Immunol. 16, 432–445 (2023).

Matsuzawa, S. et al. IL-9 enhances the growth of human mast cell progenitors under stimulation with stem cell factor. J. Immunol. 170, 3461–3467 (2003).

Nagata, K. & Nishiyama, C. IL-10 in mast cell-mediated immune responses: anti-inflammatory and proinflammatory roles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 4972 (2021).

Burton, O. T. et al. Direct effects of IL-4 on mast cells drive their intestinal expansion and increase susceptibility to anaphylaxis in a murine model of food allergy. Mucosal Immunol. 6, 740–750 (2013).

Tomar, S. et al. IL-4-BATF signaling directly modulates IL-9 producing mucosal mast cell (MMC9) function in experimental food allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 147, 280–295 (2021).

Chen, C. Y. et al. Induction of interleukin-9-producing mucosal mast cells promotes susceptibility to IgE-mediated experimental food allergy. Immunity 43, 788–802 (2015). Identified TH2 cells and a population of Lin−IL-4hiIL-17RB−KIT+ ST2+ cells as the sources of IL-9 in the food-allergic GI tract.

Barros, K. V. et al. Evidence for involvement of IL-9 and IL-22 in cows’ milk allergy in infants. Nutrients 9, 1048 (2017).

Kulis, M. et al. High- and low-dose oral immunotherapy similarly suppress pro-allergic cytokines and basophil activation in young children. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 49, 180–189 (2019).

Son, A., Baral, I., Falduto, G. H. & Schwartz, D. M. Locus of (IL-9) control: IL9 epigenetic regulation in cellular function and human disease. Exp. Mol. Med. 56, 1331–1339 (2024).

Pajulas, A., Zhang, J. & Kaplan, M. H. The world according to IL-9. J. Immunol. 211, 7–14 (2023).

Wambre, E. et al. A phenotypically and functionally distinct human TH2 cell subpopulation is associated with allergic disorders. Sci. Transl. Med. 9, eaam9171 (2017). Important clinical demonstration that activated peanut-reactive TH2 cells that express IL-9 are increased in frequency in peanut-allergic individuals following oral food challenge with peanut protein.

Hung, L., Zientara, B. & Berin, M. C. Contribution of T cell subsets to different food allergic diseases. Immunol. Rev. 326, 35–47 (2024).

Makiya, M. A. et al. Distinct CRTH2+ CD161+ (peTh2) memory CD4+ T-cell cytokine profiles in food allergy and eosinophilic gastrointestinal disorders. Clin. Exp. Allergy. 53, 1031–1040 (2023).

Brough, H. A. et al. IL-9 is a key component of memory TH cell peanut-specific responses from children with peanut allergy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 134, 1329–1338.e1310 (2014).

Xie, J. et al. Elevated antigen-driven IL-9 responses are prominent in peanut allergic humans. PLoS ONE 7, e45377 (2012).

Jabeen, R. et al. Th9 cell development requires a BATF-regulated transcriptional network. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 4641–4653 (2013).

Tsuda, M. et al. A role for BATF3 in TH9 differentiation and T-cell-driven mucosal pathologies. Mucosal Immunol. 12, 644–655 (2019).

Abdul Qayum, A. et al. The Il9 CNS-25 regulatory element controls mast cell and basophil IL-9 production. J. Immunol. 203, 1111–1121 (2019).

Mascarell, L. et al. Oral dendritic cells mediate antigen-specific tolerance by stimulating TH1 and regulatory CD4+ T cells. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 122, 603–609.e605 (2008).

Shojaei, A. H., Berner, B. & Xiaoling, L. Transbuccal delivery of acyclovir: I. In vitro determination of routes of buccal transport. Pharm. Res. 15, 1182–1188 (1998).

Campisi, G. et al. Human buccal mucosa as an innovative site of drug delivery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 16, 641–652 (2010).

McDole, J. R. et al. Goblet cells deliver luminal antigen to CD103+ dendritic cells in the small intestine. Nature 483, 345–349 (2012). Original description of goblet cell-associated antigen passages.

Wasserman, R. L., Jones, D. H. & Windom, H. H. Oral immunotherapy for food allergy: the FAST perspective. Ann. Allergy, Asthma Immunol. 121, 272–275 (2018).

Trevisonno, J. et al. Age-related food aversion and anxiety represent primary patient barriers to food oral immunotherapy. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. Pract. 12, 1809–1818.e1803 (2024).

Basso, A. S. et al. Neural correlates of IgE-mediated food allergy. J. Neuroimmunol. 140, 69–77 (2003).

Costa-Pinto, F. A., Basso, A. S., Britto, L. R., Malucelli, B. E. & Russo, M. Avoidance behavior and neural correlates of allergen exposure in a murine model of asthma. Brain Behav. Immun. 19, 52–60 (2005).

Cara, D. C., Conde, A. A. & Vaz, N. M. Immunological induction of flavor aversion in mice. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 27, 1331–1341 (1994).

Cara, D. C., Conde, A. A. & Vaz, N. M. Immunological induction of flavour aversion in mice. II. Passive/adoptive transfer and pharmacological inhibition. Scand. J. Immunol. 45, 16–20 (1997).

Plum, T. et al. Mast cells link immune sensing to antigen-avoidance behaviour. Nature 620, 634–642 (2023). Demonstrated that allergen-specific avoidance behaviour depends on mast cells and IgE.

Borner, T. et al. GDF15 induces anorexia through nausea and emesis. Cell Metab. 31, 351–362.e355 (2020).

Zhang, C. et al. Area postrema cell types that mediate nausea-associated behaviors. Neuron 109, 461–472.e465 (2021).

Coll, A. P. et al. GDF15 mediates the effects of metformin on body weight and energy balance. Nature 578, 444–448 (2020).

Florsheim, E. B. et al. Immune sensing of food allergens promotes avoidance behaviour. Nature 620, 643–650 (2023). Experimental evidence showing that allergen-induced avoidance behaviour required cysteinyl leukotrienes and that cysteinyl leukotrienes promote GDF15 secretion from IECs.

Ramesh, M. & Lieberman, J. A. Adult-onset food allergies. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol. 119, 111–119 (2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

N.W.L. is the Chief Scientific Officer for Opsidio, which is developing antibodies to stem cell factor to target mast cells. S.P.H. receives research funding from Regeneron Pharmaceuticals.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Immunology thanks H. Sampson, P. Turner and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Glossary

- Alarmins

-

Alarmins are endogenous damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) released during cellular stress, trauma or necrosis that function as early immunological danger signals. Three key epithelial-derived alarmins — TSLP, IL-25 and IL-33 act primarily through innate lymphoid cells type 2 (ILC2s) and dendritic cells to orchestrate type 2 immune responses and contribute to the pathobiology and pathophysiology of allergic responses.

- Atopic dermatitis

-

Also known as eczema, is the most common chronic skin disease of young children characterized by pruritic (itching) skin lesions. A chronic inflammatory response induces redness, swelling, itching and cracking of the skin layer, which causes weakening of the skin barrier and permits environmental and food allergen penetration.

- Filaggrin

-

Filaggrin (filament-aggregating protein) is a key structural protein essential for terminal differentiation of the epidermis and formation of the skin barrier.

- Oral tolerance

-

An active process of local and systemic immune unresponsiveness to orally delivered antigens, including food.

- Petechiae

-

A skin condition that appears as small red, purple or brown spots resulting from capillary leakage.

- TMEM79

-

A transmembrane protein that contributes to epidermal integrity and skin barrier function.

- Tryptase

-

Alpha-tryptase is a mast cell-derived protease.

- Wheal-and-flare reaction

-

The wheal-and-flare response is a type of immediate hypersensitivity reaction that can occur within minutes of an allergen being injected into the skin. It is characterized by the raising of the skin (swelling) at the injection site because of fluid leaking into the tissue (wheal). This followed by redness of the skin, resulting from the dilation of blood vessels (flare). A wheal-and-flare reaction is a result of immunoglobulin E-dependent basophils and mast cells activation.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lukacs, N.W., Hogan, S.P. Food allergy: begin at the skin, end at the mast cell?. Nat Rev Immunol 25, 783–797 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-025-01185-y

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41577-025-01185-y