Abstract

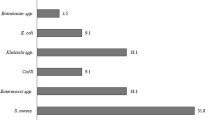

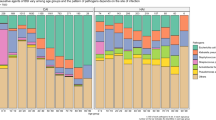

Bloodstream infections (BSIs) are common in hospitals, often life-threatening and increasing in prevalence. Microorganisms in the blood are usually rapidly cleared by the immune system and filtering organs but, in some cases, they can cause an acute infection and trigger sepsis, a systemic response to infection that leads to circulatory collapse, multiorgan dysfunction and death. Most BSIs are caused by bacteria, although fungi also contribute to a substantial portion of cases. Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus, Klebsiella pneumoniae and Candida albicans are leading causes of BSIs, although their prevalence depends on patient demographics and geographical region. Each species is equipped with unique factors that aid in the colonization of initial sites and dissemination and survival in the blood, and these factors represent potential opportunities for interventions. As many pathogens become increasingly resistant to antimicrobials, new approaches to diagnose and treat BSIs at all stages of infection are urgently needed. In this Review, we explore the prevalence of major BSI pathogens, prominent mechanisms of BSI pathogenesis, opportunities for prevention and diagnosis, and treatment options.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kontula, K. S. K., Skogberg, K., Ollgren, J., Järvinen, A. & Lyytikäinen, O. Population-based study of bloodstream infection incidence and mortality rates, Finland, 2004-2018. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 27, 2560–2569 (2021).

Diekema, D. J. et al. The microbiology of bloodstream infection: 20-year trends from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 63, e00355-19 (2019).

Wisplinghoff, H. et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 39, 309–317 (2004).

Marra, A. R. et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in Brazilian hospitals: analysis of 2,563 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 1866–1871 (2011).

Verway, M. et al. Prevalence and mortality associated with bloodstream organisms: a population-wide retrospective cohort study. J. Clin. Microbiol. 60, e0242921 (2022).

Wisplinghoff, H. et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in pediatric patients in United States hospitals: epidemiology, clinical features and susceptibilities. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 22, 686–691 (2003).

Smith, D. A. & Nehring, S. M. Bacteremia (StatPearls Publishing, 2023).

Casadevall, A. & Pirofski, L. A. The damage-response framework of microbial pathogenesis. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 1, 17–24 (2003).

Seifert, H. The clinical importance of microbiological findings in the diagnosis and management of bloodstream infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48, S238–S245 (2009).

Viscoli, C. Bloodstream infections: the peak of the iceberg. Virulence 7, 248–251 (2016).

Holmes, C. L., Anderson, M. T., Mobley, H. L. T. & Bachman, M. A. Pathogenesis of gram-negative bacteremia. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 34, e00234-20 (2021).

Kwiecinski, J. M. & Horswill, A. R. Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections: pathogenesis and regulatory mechanisms. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 53, 51–60 (2020).

Shon, A. S., Bajwa, R. P. & Russo, T. A. Hypervirulent (hypermucoviscous) Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new and dangerous breed. Virulence 4, 107–118 (2013).

Russo, T. A. & Marr, C. M. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32, e00001-19 (2019).

Brouwer, M. C., Tunkel, A. R. & van de Beek, D. Epidemiology, diagnosis, and antimicrobial treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23, 467–492 (2010).

Durand, M. L. Endophthalmitis. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 19, 227–234 (2013).

Wertheim, H. F. et al. The role of nasal carriage in Staphylococcus aureus infections. Lancet Infect. Dis. 5, 751–762 (2005).

Singer, M. et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315, 801–810 (2016).

Hajj, J., Blaine, N., Salavaci, J. & Jacoby, D. The “centrality of sepsis”: a review on incidence, mortality, and cost of care. Healthcare 6, 90 (2018).

Antimicrobial Resistance Collaborators. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022).

O’Neill, J. Tackling Drug-Resistant Infections Globally: Final Report and Recommendations (Review on Antimicrobial Resistance, 2016).

Dehbanipour, R. & Ghalavand, Z. Anti-virulence therapeutic strategies against bacterial infections: recent advances. Germs 12, 262–275 (2022).

Naber, C. K. Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and management strategies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48, S231–S237 (2009).

Wilson, J. et al. Trends in sources of meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteraemia: data from the national mandatory surveillance of MRSA bacteraemia in England, 2006-2009. J. Hosp. Infect. 79, 211–217 (2011).

Becker, K., Heilmann, C. & Peters, G. Coagulase-negative staphylococci. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 27, 870–926 (2014).

Francois Watkins, L. K. et al. Epidemiology of invasive group B streptococcal infections among nonpregnant adults in the United States, 2008-2016. JAMA Intern. Med. 179, 479–488 (2019).

Kallonen, T. et al. Systematic longitudinal survey of invasive Escherichia coli in England demonstrates a stable population structure only transiently disturbed by the emergence of ST131. Genome Res. 27, 1437–1449 (2017).

Decano, A. G. & Downing, T. An Escherichia coli ST131 pangenome atlas reveals population structure and evolution across 4,071 isolates. Sci. Rep. 9, 17394 (2019).

Mills, E. G. et al. A one-year genomic investigation of Escherichia coli epidemiology and nosocomial spread at a large US healthcare network. Genome Med. 14, 147 (2022).

Brumwell, A. et al. Escherichia coli ST131 associated with increased mortality in bloodstream infections from urinary tract source. J. Clin. Microbiol. 61, e0019923 (2023).

Burgaya, J. et al. The bacterial genetic determinants of Escherichia coli capacity to cause bloodstream infections in humans. PLoS Genet. 19, e1010842 (2023).

Daga, A. P. et al. Escherichia coli bloodstream infections in patients at a university hospital: virulence factors and clinical characteristics. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9, 191 (2019).

Martin, R. M. & Bachman, M. A. Colonization, infection, and the accessory genome of Klebsiella pneumoniae. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 8, 4 (2018).

Magill, S. S. et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 1198–1208 (2014).

Anderson, M. T., Mitchell, L. A., Zhao, L. & Mobley, H. L. T. Citrobacter freundii fitness during bloodstream infection. Sci. Rep. 8, 11792 (2018).

Subashchandrabose, S. et al. Acinetobacter baumannii genes required for bacterial survival during bloodstream infection. mSphere 1, e00013-15 (2016).

Crepin, S. et al. The lytic transglycosylase MltB connects membrane homeostasis and in vivo fitness of Acinetobacter baumannii. Mol. Microbiol. 109, 745–762 (2018).

Crépin, S. et al. The UDP-GalNAcA biosynthesis genes gna-gne2 are required to maintain cell envelope integrity and in vivo fitness in multi-drug resistant Acinetobacter baumannii. Mol. Microbiol. 113, 153–172 (2020).

Smith, S. N., Hagan, E. C., Lane, M. C. & Mobley, H. L. Dissemination and systemic colonization of uropathogenic Escherichia coli in a murine model of bacteremia. mBio 1, e00262-10 (2010).

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/media/pdfs/ar-threats-2013-508.pdf (2013).

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 Antibiotic Resistance Threats Report https://www.cdc.gov/antimicrobial-resistance/data-research/threats/index.html (2019).

Kang, C. I. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: risk factors for mortality and influence of delayed receipt of effective antimicrobial therapy on clinical outcome. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37, 745–751 (2003).

Vitkauskienė, A., Skrodenienė, E., Dambrauskienė, A., Macas, A. & Sakalauskas, R. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: resistance to antibiotics, risk factors, and patient mortality. Medicina 46, 490–495 (2010).

Pfaller, M. A., Diekema, D. J., Turnidge, J. D., Castanheira, M. & Jones, R. N. Twenty years of the SENTRY antifungal surveillance program: results for Candida species from 1997-2016. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 6, S79–S94 (2019).

Bongomin, F., Gago, S., Oladele, R. O. & Denning, D. W. Global and multi-national prevalence of fungal diseases-estimate precision. J. Fungi 3, 57 (2017).

Pappas, P. G. et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of candidiasis: 2016 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 62, e1–e50 (2016).

Mitchell, B. G. et al. The incidence of nosocomial bloodstream infection and urinary tract infection in Australian hospitals before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time series study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 12, 61 (2023).

Anderson, F. M. et al. Candida albicans selection for human commensalism results in substantial within-host diversity without decreasing fitness for invasive disease. PLoS Biol. 21, e3001822 (2023).

Satoh, K. et al. Candida auris sp. nov., a novel ascomycetous yeast isolated from the external ear canal of an inpatient in a Japanese hospital. Microbiol. Immunol. 53, 41–44 (2009).

Doğan, Ö. et al. Effect of initial antifungal therapy on mortality among patients with bloodstream infections with different Candida species and resistance to antifungal agents: a multicentre observational study by the Turkish Fungal Infections Study Group. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 56, 105992 (2020).

Al-Musawi, T. S., Alkhalifa, W. A., Alasaker, N. A., Rahman, J. U. & Alnimr, A. M. A seven-year surveillance of Candida bloodstream infection at a university hospital in KSA. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 16, 184–190 (2021).

Snitkin, E. S. et al. Tracking a hospital outbreak of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae with whole-genome sequencing. Sci. Transl. Med. 4, 148ra116 (2012).

Yarovoy, J. Y., Monte, A. A., Knepper, B. C. & Young, H. L. Epidemiology of community-onset Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. West J. Emerg. Med. 20, 438–442 (2019).

Woodward, S. E. et al. Gastric acid and escape to systemic circulation represent major bottlenecks to host infection by Citrobacter rodentium. ISME J. 17, 36–46 (2023).

Borenshtein, D. & Schauer, D. B. In: The Prokaryotes: Volume 6: Proteobacteria: Gamma Subclass (eds Martin, D. et al.) 90-98 (Springer, 2006).

Broadley, S. P. et al. Dual-track clearance of circulating bacteria balances rapid restoration of blood sterility with induction of adaptive immunity. Cell Host Microbe 20, 36–48 (2016).

Otto, G., Magnusson, M., Svensson, M., Braconier, J. & Svanborg, C. pap genotype and P fimbrial expression in Escherichia coli causing bacteremic and nonbacteremic febrile urinary tract infection. Clin. Infect. Dis. 32, 1523–1531 (2001).

Rijavec, M., Müller-Premru, M., Zakotnik, B. & Žgur-Bertok, D. Virulence factors and biofilm production among Escherichia coli strains causing bacteraemia of urinary tract origin. J. Med. Microbiol. 57, 1329–1334 (2008).

Krawczyk, B. et al. Characterisation of Escherichia coli isolates from the blood of haematological adult patients with bacteraemia: translocation from gut to blood requires the cooperation of multiple virulence factors. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 34, 1135–1143 (2015).

Schwarzer, C., Fischer, H. & Machen, T. E. Chemotaxis and binding of Pseudomonas aeruginosa to scratch-wounded human cystic fibrosis airway epithelial cells. PLoS One 11, e0150109 (2016).

Santana, D. J. et al. A Candida auris-specific adhesin, Scf1, governs surface association, colonization, and virulence. Science 381, 1461–1467 (2023).

Huang, H. Y. et al. Usefulness of EQUAL Candida Score for predicting outcomes in patients with candidaemia: a retrospective cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 26, 1501–1506 (2020).

Lee, W. J. et al. Pediatric Candida bloodstream infections complicated with mixed and subsequent bacteremia: the clinical characteristics and impacts on outcomes. J. Fungi 8, 1155 (2022).

Chen, Y. N. et al. Clinical and microbiological characteristics of neonates with candidemia and impacts of therapeutic strategies on the outcomes. J. Fungi 8, 465 (2022).

de Groot, P. W., Bader, O., de Boer, A. D., Weig, M. & Chauhan, N. Adhesins in human fungal pathogens: glue with plenty of stick. Eukaryot. Cell 12, 470–481 (2013).

Ramage, G., Martínez, J. P. & López-Ribot, J. L. Candida biofilms on implanted biomaterials: a clinically significant problem. FEMS Yeast Res. 6, 979–986 (2006).

Kuipers, A. et al. The Staphylococcus aureus polysaccharide capsule and Efb-dependent fibrinogen shield act in concert to protect against phagocytosis. Microbiology 162, 1185–1194 (2016).

Gorrie, C. L. et al. Gastrointestinal carriage is a major reservoir of Klebsiella pneumoniae infection in intensive care patients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 65, 208–215 (2017).

Martin, R. M. et al. Molecular epidemiology of colonizing and infecting isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae. mSphere 1, e00261-16 (2016).

Vornhagen, J. et al. A plasmid locus associated with Klebsiella clinical infections encodes a microbiome-dependent gut fitness factor. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009537 (2021).

Hudson, A. W., Barnes, A. J., Bray, A. S., Ornelles, D. A. & Zafar, M. A. Klebsiella pneumoniae l-fucose metabolism promotes gastrointestinal colonization and modulates its virulence determinants. Infect. Immun. 90, e0020622 (2022).

Wong Fok Lung, T. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae induces host metabolic stress that promotes tolerance to pulmonary infection. Cell Metab. 34, 761–774.e9 (2022).

Ahn, D. et al. An acquired acyltransferase promotes Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 respiratory infection. Cell Rep. 35, 109196 (2021).

Xiong, H. et al. Innate lymphocyte/Ly6Chi monocyte crosstalk promotes Klebsiella pneumoniae clearance. Cell 165, 679–689 (2016).

Xiong, H. et al. Distinct contributions of neutrophils and CCR2+ monocytes to pulmonary clearance of different Klebsiella pneumoniae strains. Infect. Immun. 83, 3418–3427 (2015).

Sá-Pessoa, J. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae reduces SUMOylation to limit host defense responses. mBio 11, e01733-20 (2020).

Bachman, M. A. et al. Genome-wide identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae fitness genes during lung infection. mBio 6, e00775 (2015).

Lawlor, M. S., Hsu, J., Rick, P. D. & Miller, V. L. Identification of Klebsiella pneumoniae virulence determinants using an intranasal infection model. Mol. Microbiol. 58, 1054–1073 (2005).

Bachman, M. A., Lenio, S., Schmidt, L., Oyler, J. E. & Weiser, J. N. Interaction of lipocalin 2, transferrin, and siderophores determines the replicative niche of Klebsiella pneumoniae during pneumonia. mBio 3, e00224-11 (2012).

Clark, J. R. & Maresso, A. M. Comparative pathogenomics of Escherichia coli: polyvalent vaccine target identification through virulome analysis. Infect. Immun. 89, e0011521 (2021).

McCarthy, K. L., Wailan, A. M., Jennison, A. V., Kidd, T. J. & Paterson, D. L. P. aeruginosa blood stream infection isolates: a “full house” of virulence genes in isolates associated with rapid patient death and patient survival. Microb. Pathog. 119, 81–85 (2018).

Inclan, Y. F. et al. A scaffold protein connects type IV pili with the Chp chemosensory system to mediate activation of virulence signaling in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 101, 590–605 (2016).

Persat, A., Inclan, Y. F., Engel, J. N., Stone, H. A. & Gitai, Z. Type IV pili mechanochemically regulate virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 7563–7568 (2015).

Geiser, T. K., Kazmierczak, B. I., Garrity-Ryan, L. K., Matthay, M. A. & Engel, J. N. Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoT inhibits in vitro lung epithelial wound repair. Cell Microbiol. 3, 223–236 (2001).

Rutherford, V. et al. Environmental reservoirs for exoS+ and exoU+ strains of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Env. Microbiol. Rep. 10, 485–492 (2018).

Shaver, C. M. & Hauser, A. R. Relative contributions of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ExoU, ExoS, and ExoT to virulence in the lung. Infect. Immun. 72, 6969–6977 (2004).

Garrity-Ryan, L. et al. The arginine finger domain of ExoT contributes to actin cytoskeleton disruption and inhibition of internalization of Pseudomonas aeruginosa by epithelial cells and macrophages. Infect. Immun. 68, 7100–7113 (2000).

Rangel, S. M., Diaz, M. H., Knoten, C. A., Zhang, A. & Hauser, A. R. The role of ExoS in dissemination of Pseudomonas aeruginosa during pneumonia. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004945 (2015).

Golovkine, G. et al. VE-cadherin cleavage by LasB protease from Pseudomonas aeruginosa facilitates type III secretion system toxicity in endothelial cells. PLoS Pathog. 10, e1003939 (2014).

Heggers, J. P. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A: its role in retardation of wound healing: the 1992 lindberg award. J. Burn Care Rehabil. 13, 512–518 (1992).

Pont, S., Janet-Maitre, M., Faudry, E., Cretin, F. & Attrée, I. Molecular mechanisms involved in Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1386, 325–345 (2022).

Guttman, J. A. & Finlay, B. B. Tight junctions as targets of infectious agents. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1788, 832–841 (2009).

Vikström, E., Bui, L., Konradsson, P. & Magnusson, K. E. The junctional integrity of epithelial cells is modulated by Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing molecule through phosphorylation-dependent mechanisms. Exp. Cell Res. 315, 313–326 (2009).

Vikström, E., Tafazoli, F. & Magnusson, K. E. Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing molecule N-(3 oxododecanoyl)-l-homoserine lactone disrupts epithelial barrier integrity of Caco-2 cells. FEBS Lett. 580, 6921–6928 (2006).

Johnson, J. R. et al. Host characteristics and bacterial traits predict experimental virulence for Escherichia coli bloodstream isolates from patients with urosepsis. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2, ofv083 (2015).

Spurbeck, R. R. et al. Escherichia coli isolates that carry vat, fyuA, chuA, and yfcV efficiently colonize the urinary tract. Infect. Immun. 80, 4115–4122 (2012).

Shea, A. E., Frick-Cheng, A. E., Smith, S. N. & Mobley, H. L. T. Phenotypic assessment of clinical Escherichia coli isolates as an indicator for uropathogenic potential. mSystems 7, e0082722 (2022).

Royer, G. et al. Epistatic interactions between the high pathogenicity island and other iron uptake systems shape Escherichia coli extra-intestinal virulence. Nat. Commun. 14, 3667 (2023).

Holden, V. I., Breen, P., Houle, S., Dozois, C. M. & Bachman, M. A. Klebsiella pneumoniae siderophores induce inflammation, bacterial dissemination, and HIF-1α stabilization during pneumonia. mBio 7, e01397-16 (2016).

Rogga, V. & Kosalec, I. Untying the anchor for the lipopolysaccharide: lipid A structural modification systems offer diagnostic and therapeutic options to tackle polymyxin resistance. Arh. Hig. Rada Toksikol. 74, 145–166 (2023).

Wang, C. Y. et al. Prc contributes to Escherichia coli evasion of classical complement-mediated serum killing. Infect. Immun. 80, 3399–3409 (2012).

Som, N. & Reddy, M. Cross-talk between phospholipid synthesis and peptidoglycan expansion by a cell wall hydrolase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2300784120 (2023).

Khadka, S. et al. Urine-mediated suppression of Klebsiella pneumoniae mucoidy is counteracted by spontaneous Wzc variants altering capsule chain length. mSphere 8, e0028823 (2023).

Walker, K. A., Treat, L. P., Sepúlveda, V. E. & Miller, V. L. The small protein RmpD drives hypermucoviscosity in Klebsiella pneumoniae. mBio 11, e01750-20 (2020).

Mike, L. A. et al. A systematic analysis of hypermucoviscosity and capsule reveals distinct and overlapping genes that impact Klebsiella pneumoniae fitness. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009376 (2021).

Marr, C. M. & Russo, T. A. Hypervirulent Klebsiella pneumoniae: a new public health threat. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 17, 71–73 (2019).

Crosby, H. A. et al. The Staphylococcus aureus global regulator MgrA modulates clumping and virulence by controlling surface protein expression. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005604 (2016).

McAdow, M. et al. Preventing Staphylococcus aureus sepsis through the inhibition of its agglutination in blood. PLoS Pathog. 7, e1002307 (2011).

Surewaard, B. G. J. et al. α-Toxin induces platelet aggregation and liver injury during Staphylococcus aureus sepsis. Cell Host Microbe 24, 271–284.e3 (2018).

Liesenborghs, L., Verhamme, P. & Vanassche, T. Staphylococcus aureus, master manipulator of the human hemostatic system. J. Thromb. Haemost. 16, 441–454 (2018).

Claes, J. et al. Clumping factor A, von Willebrand factor-binding protein and von Willebrand factor anchor Staphylococcus aureus to the vessel wall. J. Thromb. Haemost. 15, 1009–1019 (2017).

Gupta, E. et al. Unravelling the differential host immuno-inflammatory responses to Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli infections in sepsis. Vaccines 10, 1648 (2022).

Bassetti, M. et al. Characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia and predictors of early and late mortality. PLoS One 12, e0170236 (2017).

García-Solache, M. & Rice, L. B. The enterococcus: a model of adaptability to its environment. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 32, e00058-18 (2019).

Hong, Y. Q. & Ghebrehiwet, B. Effect of Pseudomonas aeruginosa elastase and alkaline protease on serum complement and isolated components C1q and C3. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 62, 133–138 (1992).

Laarman, A. J. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alkaline protease blocks complement activation via the classical and lectin pathways. J. Immunol. 188, 386–393 (2012).

Schmidtchen, A., Holst, E., Tapper, H. & Björck, L. Elastase-producing Pseudomonas aeruginosa degrade plasma proteins and extracellular products of human skin and fibroblasts, and inhibit fibroblast growth. Microb. Pathog. 34, 47–55 (2003).

Schultz, D. R. & Miller, K. D. Elastase of Pseudomonas aeruginosa: inactivation of complement components and complement-derived chemotactic and phagocytic factors. Infect. Immun. 10, 128–135 (1974).

Weber, B., Nickol, M. M., Jagger, K. S. & Saelinger, C. B. Interaction of Pseudomonas exoproducts with phagocytic cells. Can. J. Microbiol. 28, 679–685 (1982).

Pedersen, S. S., Kharazmi, A., Espersen, F. & Høiby, N. Pseudomonas aeruginosa alginate in cystic fibrosis sputum and the inflammatory response. Infect. Immun. 58, 3363–3368 (1990).

Pier, G. B., Coleman, F., Grout, M., Franklin, M. & Ohman, D. E. Role of alginate O acetylation in resistance of mucoid Pseudomonas aeruginosa to opsonic phagocytosis. Infect. Immun. 69, 1895–1901 (2001).

Kintz, E., Scarff, J. M., DiGiandomenico, A. & Goldberg, J. B. Lipopolysaccharide O-antigen chain length regulation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa serogroup O11 strain PA103. J. Bacteriol. 190, 2709–2716 (2008).

Hallström, T. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase (Lpd) to bind to the human terminal pathway regulators vitronectin and clusterin to inhibit terminal pathway complement attack. PLoS One 10, e0137630 (2015).

Patricio, P., Paiva, J. A. & Borrego, L. M. Immune response in bacterial and Candida sepsis. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 9, 105–113 (2019).

Kashem, S. W. et al. Candida albicans morphology and dendritic cell subsets determine T helper cell differentiation. Immunity 42, 356–366 (2015).

Lionakis, M. S., Iliev, I. D. & Hohl, T. M. Immunity against fungi. JCI Insight 2, e93156 (2017).

Holmes, C. L. et al. Insight into neutrophil extracellular traps through systematic evaluation of citrullination and peptidylarginine deiminases. J. Immunol. Res. 2019, 2160192 (2019).

Johnson, C. J. et al. The extracellular matrix of Candida albicans biofilms impairs formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005884 (2016).

Kernien, J. F., Johnson, C. J. & Nett, J. E. Conserved inhibition of neutrophil extracellular trap release by clinical Candida albicans biofilms. J. Fungi 3, 49 (2017).

Johnson, C. J., Davis, J. M., Huttenlocher, A., Kernien, J. F. & Nett, J. E. Emerging fungal pathogen candida auris evades neutrophil attack. mBio 9, e01403-18 (2018).

Huang, X. et al. Capsule type defines the capability of Klebsiella pneumoniae in evading Kupffer cell capture in the liver. PLoS Pathog. 18, e1010693 (2022).

Holmes, C. L. et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae causes bacteremia using factors that mediate tissue-specific fitness and resistance to oxidative stress. PLoS Pathog. 19, e1011233 (2023).

Holmes, C. L. et al. The ADP-heptose biosynthesis enzyme gmhb is a conserved gram-negative bacteremia fitness factor. Infect. Immun. 90, e0022422 (2022).

Søgaard, M., Nørgaard, M., Dethlefsen, C. & Schønheyder, H. C. Temporal changes in the incidence and 30-day mortality associated with bacteremia in hospitalized patients from 1992 through 2006: a population-based cohort study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 52, 61–69 (2011).

Poolman, J. T. & Anderson, A. S. Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus: leading bacterial pathogens of healthcare associated infections and bacteremia in older-age populations. Expert Rev. Vaccines 17, 607–618 (2018).

Uslan, D. Z. et al. Age- and sex-associated trends in bloodstream infection: a population-based study in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Arch. Intern. Med. 167, 834–839 (2007).

Graff, L. R. et al. Antimicrobial therapy of gram-negative bacteremia at two university-affiliated medical centers. Am. J. Med. 112, 204–211 (2002).

Vidal, F. et al. Bacteraemia in adults due to glucose non-fermentative Gram-negative bacilli other than P. aeruginosa. QJM 96, 227–234 (2003).

Kaasch, A. J. et al. Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection: a pooled analysis of five prospective, observational studies. J. Infect. 68, 242–251 (2014).

Quagliarello, B. et al. Strains of Staphylococcus aureus obtained from drug-use networks are closely linked. Clin. Infect. Dis. 35, 671–677 (2002).

Bou-Antoun, S. et al. Descriptive epidemiology of Escherichia coli bacteraemia in England, April 2012 to March 2014. Eur. Surveill. 21, 30329 (2016).

Anderson, D. J. et al. Seasonal variation in Klebsiella pneumoniae bloodstream infection on 4 continents. J. Infect. Dis. 197, 752–756 (2008).

Rao, K. et al. Risk factors for Klebsiella infections among hospitalized patients with preexisting colonization. mSphere 6, e0013221 (2021).

Boyer, K. M. & Gotoff, S. P. Strategies for chemoprophylaxis of GBS early-onset infections. Antibiot. Chemother. 35, 267–280 (1985).

Verani, J. R., McGee, L., Schrag, S. J. & Division of Bacterial Diseases, National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Prevention of perinatal group B streptococcal disease — revised guidelines from CDC, 2010. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 59, 1–36 (2010).

Mergenhagen, K. A. et al. Determining the utility of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus nares screening in antimicrobial stewardship. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, 1142–1148 (2020).

Popovich, K. J. et al. SHEA/IDSA/APIC practice recommendation: strategies to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus transmission and infection in acute-care hospitals: 2022 update. Infect. Control. Hosp. Epidemiol. 44, 1039–1067 (2023).

Seidelman, J. L., Mantyh, C. R. & Anderson, D. J. Surgical site infection prevention: a review. JAMA 329, 244–252 (2023).

Nicolle, L. E. et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 68, e83–e110 (2019).

Tops, S. C. M. et al. Rectal culture-based versus empirical antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent infectious complications in men undergoing transrectal prostate biopsy: a randomized, nonblinded multicenter trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 76, 1188–1196 (2023).

Jacewicz, M. et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no antibiotic prophylaxis in transperineal prostate biopsies (NORAPP): a randomised, open-label, non-inferiority trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 22, 1465–1471 (2022).

Taur, Y. et al. Intestinal domination and the risk of bacteremia in patients undergoing allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin. Infect. Dis. 55, 905–914 (2012).

Sun, Y. et al. Measurement of Klebsiella intestinal colonization density to assess infection risk. mSphere 6, e0050021 (2021).

Vornhagen, J. et al. Combined comparative genomics and clinical modeling reveals plasmid-encoded genes are independently associated with Klebsiella infection. Nat. Commun. 13, 4459 (2022).

Gargiullo, L., Del Chierico, F., D’Argenio, P. & Putignani, L. Gut microbiota modulation for multidrug-resistant organism decolonization: present and future perspectives. Front. Microbiol. 10, 1704 (2019).

Lee, C. C. et al. Prediction of community-onset bacteremia among febrile adults visiting an emergency department: rigor matters. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 73, 168–173 (2012).

Fabre, V. et al. Does this patient need blood cultures? A scoping review of indications for blood cultures in adult nonneutropenic inpatients. Clin. Infect. Dis. 71, 1339–1347 (2020).

López-Cortés, L. E. et al. Efficacy and safety of a structured de-escalation from antipseudomonal β-lactams in bloodstream infections due to Enterobacterales (SIMPLIFY): an open-label, multicentre, randomised trial. Lancet Infect. Dis. 24, 375–385 (2024).

Yahav, D. et al. Seven versus 14 days of antibiotic therapy for uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia: a noninferiority randomized controlled trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 69, 1091–1098 (2019).

Holland, T. L. et al. Effect of algorithm-based therapy vs usual care on clinical success and serious adverse events in patients with staphylococcal bacteremia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 320, 1249–1258 (2018).

von Dach, E. et al. Effect of C-reactive protein-guided antibiotic treatment duration, 7-day treatment, or 14-day treatment on 30-day clinical failure rate in patients with uncomplicated gram-negative bacteremia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 323, 2160–2169 (2020).

Iversen, K. et al. Partial oral versus intravenous antibiotic treatment of endocarditis. N. Engl. J. Med. 380, 415–424 (2019).

Kawasuji, H. et al. Effectiveness and safety of linezolid versus vancomycin, teicoplanin, or daptomycin against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Antibiotics 12, 697 (2023).

Sutton, J. D. et al. Oral β-lactam antibiotics vs fluoroquinolones or trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for definitive treatment of Enterobacterales bacteremia from a urine source. JAMA Netw. Open 3, e2020166 (2020).

Tong, S. Y. C. et al. Effect of vancomycin or daptomycin with vs without an antistaphylococcal β-lactam on mortality, bacteremia, relapse, or treatment failure in patients with MRSA bacteremia: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 323, 527–537 (2020).

Cosgrove, S. E. et al. Initial low-dose gentamicin for Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia and endocarditis is nephrotoxic. Clin. Infect. Dis. 48, 713–721 (2009).

Babich, T. et al. Combination versus monotherapy as definitive treatment for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteraemia: a multicentre retrospective observational cohort study. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 76, 2172–2181 (2021).

Kaye, K. S. et al. Colistin monotherapy versus combination therapy for carbapenem-resistant organisms. NEJM Evid. 2, https://doi.org/10.1056/evidoa2200131 (2023).

Jones, F., Hu, Y. & Coates, A. The efficacy of using combination therapy against multi-drug and extensively drug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in clinical settings. Antibiotics 11, 323 (2022).

Tschudin-Sutter, S., Fosse, N., Frei, R. & Widmer, A. F. Combination therapy for treatment of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections. PLoS One 13, e0203295 (2018).

McDanel, J. S. et al. Comparative effectiveness of beta-lactams versus vancomycin for treatment of methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infections among 122 hospitals. Clin. Infect. Dis. 61, 361–367 (2015).

Kim, S. H. et al. Outcome of vancomycin treatment in patients with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52, 192–197 (2008).

Albin, O. R., Patel, T. S. & Kaye, K. S. Meropenem-vaborbactam for adults with complicated urinary tract and other invasive infections. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 16, 865–876 (2018).

Thabit, A. K. et al. Antibiotic penetration into bone and joints: an updated review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 81, 128–136 (2019).

Nau, R., Sörgel, F. & Eiffert, H. Penetration of drugs through the blood-cerebrospinal fluid/blood-brain barrier for treatment of central nervous system infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 23, 858–883 (2010).

Drwiega, E. N. & Rodvold, K. A. Penetration of antibacterial agents into pulmonary epithelial lining fluid: an update. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 61, 17–46 (2022).

McKenzie, C. Antibiotic dosing in critical illness. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 66, ii25–31, (2011).

Silva, J. T. & López-Medrano, F. Cefiderocol, a new antibiotic against multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Rev. Esp. Quimioter. 34, 41–43 (2021).

Donlan, R. M. Biofilms: microbial life on surfaces. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 8, 881–890 (2002).

Thwaites, G. E. et al. Adjunctive rifampicin for Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia (ARREST): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 391, 668–678 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Use of bacteriophage in the treatment of experimental animal bacteremia from imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Int. J. Mol. Med. 17, 309–317 (2006).

Zagaliotis, P., Michalik-Provasek, J., Gill, J. J. & Walsh, T. J. Therapeutic bacteriophages for gram-negative bacterial infections in animals and humans. Pathog. Immun. 7, 1–45 (2022).

Fleitas Martínez, O., Cardoso, M. H., Ribeiro, S. M. & Franco, O. L. Recent advances in anti-virulence therapeutic strategies with a focus on dismantling bacterial membrane microdomains, toxin neutralization, quorum-sensing interference and biofilm inhibition. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 9, 74 (2019).

Ford, C. A., Hurford, I. M. & Cassat, J. E. Antivirulence strategies for the treatment of Staphylococcus aureus infections: a mini review. Front. Microbiol. 11, 632706 (2020).

Braun, L. & Cossart, P. Interactions between Listeria monocytogenes and host mammalian cells. Microbes Infect. 2, 803–811 (2000).

Hamon, M. A., Ribet, D., Stavru, F. & Cossart, P. Listeriolysin O: the Swiss army knife of Listeria. Trends Microbiol. 20, 360–368 (2012).

Vázquez-Boland, J. A. et al. Listeria pathogenesis and molecular virulence determinants. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 14, 584–640 (2001).

Alvarez-Dominguez, C., Roberts, R. & Stahl, P. D. Internalized Listeria monocytogenes modulates intracellular trafficking and delays maturation of the phagosome. J. Cell Sci. 110, 731–743 (1997).

Lasa, I., David, V., Gouin, E., Marchand, J. B. & Cossart, P. The amino-terminal part of ActA is critical for the actin-based motility of Listeria monocytogenes; the central proline-rich region acts as a stimulator. Mol. Microbiol. 18, 425–436 (1995).

Vázquez-Boland, J. A., Wagner, M. & Scortti, M. Why are some Listeria monocytogenes genotypes more likely to cause invasive (brain, placental) infection? mBio 11, https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.03126-20 (2020).

Helmy, K. Y. et al. CRIg: a macrophage complement receptor required for phagocytosis of circulating pathogens. Cell 124, 915–927 (2006).

Kim, K. H. et al. CRIg signals induce anti-intracellular bacterial phagosome activity in a chloride intracellular channel 3-dependent manner. Eur. J. Immunol. 43, 667–678 (2013).

de Jong, H. K., Parry, C. M., van der Poll, T. & Wiersinga, W. J. Host-pathogen interaction in invasive Salmonellosis. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002933 (2012).

Li, W. et al. Strategies adopted by Salmonella to survive in host: a review. Arch. Microbiol. 205, 362 (2023).

Colonne, P. M., Winchell, C. G. & Voth, D. E. Hijacking host cell highways: manipulation of the host actin cytoskeleton by obligate intracellular bacterial pathogens. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 6, 107 (2016).

Figueira, R. & Holden, D. W. Functions of the Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 (SPI-2) type III secretion system effectors. Microbiology 158, 1147–1161 (2012).

Maudet, C. et al. Bacterial inhibition of Fas-mediated killing promotes neuroinvasion and persistence. Nature 603, 900–906 (2022).

Vazquez-Torres, A. et al. Extraintestinal dissemination of Salmonella by CD18-expressing phagocytes. Nature 401, 804–808 (1999).

McClelland, M. et al. Comparison of genome degradation in Paratyphi A and Typhi, human-restricted serovars of Salmonella enterica that cause typhoid. Nat. Genet. 36, 1268–1274 (2004).

Clancy, C. J. & Nguyen, M. H. Diagnosing invasive candidiasis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 56, e01909-17 (2018).

Banerjee, R. et al. Randomized trial evaluating clinical impact of RAPid IDentification and susceptibility testing for gram-negative bacteremia: RAPIDS-GN. Clin. Infect. Dis. 73, e39–e46 (2021).

Blauwkamp, T. A. et al. Analytical and clinical validation of a microbial cell-free DNA sequencing test for infectious disease. Nat. Microbiol. 4, 663–674 (2019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Microbiology thanks Naomi O’Grady, Jesús Rodríguez-Baño, Harald Seifert and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Holmes, C.L., Albin, O.R., Mobley, H.L.T. et al. Bloodstream infections: mechanisms of pathogenesis and opportunities for intervention. Nat Rev Microbiol 23, 210–224 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-024-01105-2

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-024-01105-2