Abstract

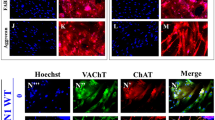

Point mutations in cysteine string protein-α (CSPα) cause dominantly inherited adult-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis (ANCL), a rapidly progressing and lethal neurodegenerative disease with no treatment. ANCL mutations are proposed to trigger CSPα aggregation/oligomerization, but the mechanism of oligomer formation remains unclear. Here we use purified proteins, mouse primary neurons and patient-derived induced neurons to show that the normally palmitoylated cysteine string region of CSPα loses palmitoylation in ANCL mutants. This allows oligomerization of mutant CSPα via ectopic binding of iron–sulfur (Fe–S) clusters. The resulting oligomerization of mutant CSPα causes its mislocalization and consequent loss of its synaptic SNARE-chaperoning function. We then find that pharmacological iron chelation mitigates the oligomerization of mutant CSPα, accompanied by partial rescue of the downstream SNARE defects and the pathological hallmark of lipofuscin accumulation. Thus, the iron chelators deferiprone (L1) and deferoxamine (Dfx), which are already used to treat iron overload in humans, offer a new approach for treating ANCL.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

$32.99 / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$259.00 per year

only $21.58 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Source data for Figs. 1–5 are provided with this paper.

References

Chamberlain, L. H. & Burgoyne, R. D. The cysteine-string domain of the secretory vesicle cysteine-string protein is required for membrane targeting. Biochem J. 335, 205–209 (1998).

Tobaben, S. et al. A trimeric protein complex functions as a synaptic chaperone machine. Neuron 31, 987–999 (2001).

Sharma, M., Burré, J. & Südhof, T. C. CSPα promotes SNARE-complex assembly by chaperoning SNAP-25 during synaptic activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 30–39 (2011).

Südhof, T. C. & Rothman, J. E. Membrane fusion: grappling with SNARE and SM proteins. Science 323, 474–477 (2009).

Benitez, B. A. et al. Exome-sequencing confirms DNAJC5 mutations as cause of adult neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis. PLoS ONE 6, e26741 (2011).

Nosková, L. et al. Mutations in DNAJC5, encoding cysteine-string protein alpha, cause autosomal-dominant adult-onset neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 89, 241–252 (2011).

Velinov, M. et al. Mutations in the gene DNAJC5 cause autosomal dominant Kufs disease in a proportion of cases: study of the Parry family and 8 other families. PLoS ONE 7, e29729 (2012).

Josephson, S. A., Schmidt, R. E., Millsap, P., McManus, D. Q. & Morris, J. C. Autosomal dominant Kufs’ disease: a cause of early onset dementia. J. Neurol. Sci. 188, 51–60 (2001).

Henderson, M. X. et al. Neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis with DNAJC5/CSPα mutation has PPT1 pathology and exhibit aberrant protein palmitoylation. Acta Neuropathol. 131, 621–637 (2015).

Zhang, Y.-Q. & Chandra, S. S. Oligomerization of cysteine string protein alpha mutants causing adult neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1842, 2136–2146 (2014).

Greaves, J. et al. Palmitoylation-induced aggregation of cysteine-string protein mutants that cause neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 37330–37339 (2012).

Diez-Ardanuy, C., Greaves, J., Munro, K. R., Tomkinson, N. C. & Chamberlain, L. H. A cluster of palmitoylated cysteines are essential for aggregation of cysteine-string protein mutants that cause neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Sci. Rep. 7, 10 (2017).

Dailey, H. A., Finnegan, M. G. & Johnson, M. K. Human ferrochelatase is an iron–sulfur protein. Biochemistry 33, 403–407 (1994).

Johansson, C., Kavanagh, K. L., Gileadi, O. & Oppermann, U. Reversible sequestration of active site cysteines in a 2Fe-2S-bridged dimer provides a mechanism for glutaredoxin 2 regulation in human mitochondria. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 3077–3082 (2007).

Mesecke, N., Mittler, S., Eckers, E., Herrmann, J. M. & Deponte, M. Two novel monothiol glutaredoxins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae provide further insight into iron-sulfur cluster binding, oligomerization, and enzymatic activity of glutaredoxins. Biochemistry 47, 1452–1463 (2008).

Gundersen, C. B., Mastrogiacomo, A., Faull, K. & Umbach, J. A. Extensive lipidation of a Torpedo cysteine string protein. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 19197–19199 (1994).

Zinsmaier, K. E. et al. A cysteine-string protein is expressed in retina and brain of Drosophila. J. Neurogenet. 7, 15–29 (1990).

Kohan, S. A. et al. Cysteine string protein immunoreactivity in the nervous system and adrenal gland of rat. J. Neurosci. 15, 6230–6238 (1995).

Martin, J. J. Adult type of neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis. Dev. Neurosci. 13, 331–338 (1991).

Goebel, H. H. & Braak, H. Adult neuronal ceroid-lipofuscinosis. Clin. Neuropathol. 8, 109–119 (1989).

Maio, N. & Rouault, T. A. Mammalian Fe–S proteins: definition of a consensus motif recognized by the co-chaperone HSC20. Metallomics 8, 1032–1046 (2016).

Rouault, T. A. Biogenesis of iron–sulfur clusters in mammalian cells: new insights and relevance to human disease. Dis. Model. Mech. 5, 155–164 (2012).

Chamberlain, L. H. & Burgoyne, R. D. The molecular chaperone function of the secretory vesicle cysteine string proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 31420–31426 (1997).

Zinsmaier, K. E., Eberle, K. K., Buchner, E., Walter, N. & Benzer, S. Paralysis and early death in cysteine string protein mutants of Drosophila. Science 263, 977–980 (1994).

Umbach, J. A. et al. Presynaptic dysfunction in Drosophila csp mutants. Neuron 13, 899–907 (1994).

Chandra, S., Gallardo, G., Fernández-Chacón, R., Schlüter, O. M. & Südhof, T. C. α-Synuclein cooperates with CSPα in preventing neurodegeneration. Cell 123, 383–396 (2005).

Sharma, M. et al. CSPα knockout causes neurodegeneration by impairing SNAP-25 function. EMBO J. 31, 829–841 (2012).

Malkin, R. & Rabinowitz, J. C. The reactivity of clostridial ferredoxin with iron chelating agents and 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid. Biochemistry 6, 3880–3891 (1967).

Tong, W.-H. & Rouault, T. A. Functions of mitochondrial ISCU and cytosolic ISCU in mammalian iron–sulfur cluster biogenesis and iron homeostasis. Cell Metab. 3, 199–210 (2006).

Baldus, W. P., Fairbanks, V. F., Dickson, E. R. & Baggenstoss, A. H. Deferoxamine-chelatable iron in hemochromatosis and other disorders of iron overload. Mayo Clin. Proc. 53, 157–165 (1978).

Hoffbrand, A. V., Cohen, A. & Hershko, C. Role of deferiprone in chelation therapy for transfusional iron overload. Blood 102, 17–24 (2003).

Abbruzzese, G. et al. A pilot trial of deferiprone for neurodegeneration with brain iron accumulation. Haematologica 96, 1708–1711 (2011).

Habgood, M. D. et al. Investigation into the correlation between the structure of hydroxypyridinones and blood-brain barrier permeability. Biochem. Pharmacol. 57, 1305–1310 (1999).

Fredenburg, A. M., Sethi, R. K., Allen, D. D. & Yokel, R. A. The pharmacokinetics and blood-brain barrier permeation of the chelators 1,2 dimethly-, 1,2 diethyl-, and 1-[ethan-1’ol]-2-methyl-3-hydroxypyridin-4-one in the rat. Toxicology 108, 191–199 (1996).

Fernández-Chacón, R. et al. The synaptic vesicle protein CSPα prevents presynaptic degeneration. Neuron 42, 237–251 (2004).

Braun, J. E. & Scheller, R. H. Cysteine string protein, a DnaJ family member, is present on diverse secretory vesicles. Neuropharmacology 34, 1361–1369 (1995).

Chamberlain, L. H. & Burgoyne, R. D. Activation of the ATPase activity of heat-shock proteins Hsc70/Hsp70 by cysteine-string protein. Biochem J. 322, 853–858 (1997).

Pang, Z. P. et al. Induction of human neuronal cells by defined transcription factors. Nature 476, 220–223 (2011).

Zhang, Y.-Q. et al. Identification of CSPα clients reveals a role in dynamin 1 regulation. Neuron 74, 136–150 (2012).

Anderson, G. W., Goebel, H. H. & Simonati, A. Human pathology in NCL. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1832, 1807–1826 (2013).

Hall, N. A., Lake, B. D., Dewji, N. N. & Patrick, A. D. Lysosomal storage of subunit c of mitochondrial ATP synthase in Batten’s disease (ceroid-lipofuscinosis). Biochem J. 275, 269–272 (1991).

Netz, D. J., Mascarenhas, J., Stehling, O., Pierik, A. J. & Lill, R. Maturation of cytosolic and nuclear iron-sulfur proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 303–312 (2014).

Piga, A. et al. Deferiprone. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1202, 75–78 (2010).

Jordan, M., Schallhorn, A. & Wurm, F. M. Transfecting mammalian cells: optimization of critical parameters affecting calcium-phosphate precipitate formation. Nucleic Acids Res. 24, 596–601 (1996).

Alvarez, S. W. et al. NFS1 undergoes positive selection in lung tumours and protects cells from ferroptosis. Nature 551, 639–643 (2017).

Maximov, A., Pang, Z. P., Tervo, D. G. R. & Südhof, T. C. Monitoring synaptic transmission in primary neuronal cultures using local extracellular stimulation. J. Neurosci. Methods 161, 75–87 (2007).

Lois, C., Hong, E. J., Pease, S., Brown, E. J. & Baltimore, D. Germline transmission and tissue-specific expression of transgenes delivered by lentiviral vectors. Science 295, 868–872 (2002).

Dull, T. et al. A third-generation lentivirus vector with a conditional packaging system. J. Virol. 72, 8463–8471 (1998).

Yee, J. K. et al. A general method for the generation of high-titer, pantropic retroviral vectors: highly efficient infection of primary hepatocytes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 91, 9564–9568 (1994).

Tamarit, J., Irazusta, V., Moreno-Cermeño, A. & Ros, J. Colorimetric assay for the quantitation of iron in yeast. Anal. Biochem. 351, 149–151 (2006).

Riemer, J., Hoepken, H. H., Czerwinska, H., Robinson, S. R. & Dringen, R. Colorimetric ferrozine-based assay for the quantitation of iron in cultured cells. Anal. Biochem. 331, 370–375 (2004).

Fogo, J. K. & Popowsky, M. Spectrophotometric determination of hydrogen sulfide - methylene blue method. Anal. Chem. 21, 732–734 (1949).

Wernig, M. et al. Tau EGFP embryonic stem cells: an efficient tool for neuronal lineage selection and transplantation. J. Neurosci. Res. 69, 918–924 (2002).

Ikegaki, N. & Kennett, R. H. Glutaraldehyde fixation of the primary antibody-antigen complex on nitrocellulose paper increases the overall sensitivity of immunoblot assay. J. Immunol. Methods 124, 205–210 (1989).

Acknowledgements

We thank T. C. Südhof for kindly sharing the CSPα knockout mouse line and antibodies against CSPα and neuronal SNARE proteins, and G. Petsko for his advice on experimental approaches and the manuscript. Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source (CHESS) experiments were supported by the National Science Foundation under award DMR-1332208. This work was supported by grants from Alzheimer’s Association (NIRG-15-363678 to MS), American Federation for Aging Research (New Investigator in Alzheimer’s Research Grant, to M.S.), NIH National Institute for Aging (1R01AG052505, to M.S.) and National Institute for Neurological Disorders and Stroke (1R01NS095988, to M.S.) and (1R01NS102181, to J.B.), as well as F31 studentship (NS098623, to N.N.N.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

N.N.N., B.E., P.K., Y.N., J.B. and M.S. designed, performed and analyzed all experiments except the X-ray fluorescence experiment, which was performed and analyzed by R.H. and Q.H. N.D. and M.T.V. contributed ANCL patient fibroblasts to the study. N.N.N., J.B. and M.S. wrote the manuscript. M.S. conceived the project and directed the research.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Peer review information Beth Moorefield was the primary editor on this article and managed its editorial process and peer review in collaboration with the rest of the editorial team.

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary figures with legends.

Source data

Source Data Fig. 1

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 2

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 3

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 4

Unprocessed western blots.

Source Data Fig. 5

Unprocessed western blots.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Naseri, N.N., Ergel, B., Kharel, P. et al. Aggregation of mutant cysteine string protein-α via Fe–S cluster binding is mitigated by iron chelators. Nat Struct Mol Biol 27, 192–201 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-020-0375-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-020-0375-y

This article is cited by

-

CHIP protects lysosomes from CLN4 mutant-induced membrane damage

Nature Cell Biology (2025)

-

Cysteine string protein α and a link between rare and common neurodegenerative dementias

npj Dementia (2025)

-

Lysosomal exocytosis releases pathogenic α-synuclein species from neurons in synucleinopathy models

Nature Communications (2022)