Abstract

In physical human–robot interaction, both humans and robots need to adapt to ensure synergetic behavior. This study investigated how humans respond to robots moving with different velocity profiles. In unconstrained human movements, velocity scales with the trajectory’s curvature, i.e., moving fast at linear segments while slowing down at curved segments. Two experiments examined humans tracking a robot that traced an elliptic path with different velocity profiles, while instructed to minimize interaction forces. Results showed involuntary forces were higher when the robot moved with constant velocity or exaggerated the biological velocity-curvature scaling. Specifically, higher angular velocities in the robot were associated with greater tangential and normal forces. Experiment 1 tested whether biomechanical constraints caused these forces by reversing movement direction, but observed differences were small. Experiment 2 explored human adaptation across three practice sessions and found that interaction forces decreased for non-biological profiles only when real-time visual feedback was provided. The force-velocity modulations weakened, indicating that humans learned to predict and compensate for inertial forces. These findings highlight the need to consider human motor limitations and learning processes in physical interaction. The results have practical implications for collaborative and wearable robots where physical contact and coordination between humans and robots are critical.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Data sets generated during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Argall, B. D. & Billard, A. G. A survey of tactile human robot interactions. Robotics and Autonomous Systems 58, 1159–1176 (2010).

De Santis, A., Siciliano, B., De Luca, A. & Bicchi, A. An atlas of physical human robot interaction. Mechanism and Machine Theory 43, 253–270 (2008).

Khatib, O., Yokoi, K., Brock, O., Chang, K. & Casal, A. Robots in human environments: Basic autonomous capabilities. International Journal of Robotics Research 18, 684–696 (1999).

Admoni, H., Shah, J. & Srinivasa, S. Editorial: Special issue on human–robot interaction. International Journal of Robotics Research 36, 459–460 (2017).

Shah, J., Wiken, J., Williams, B. & Breazeal, C. Improved human–robot team performance using chaski, a human-inspired plan execution system. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Human–Robot Interaction (HRI), 29–36 (2011).

Kwon, W. Y. & Suh, I. H. A temporal Bayesian network with application to design of a proactive robotic assistant. In Proceedings of the 2012 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 3685–3690 (2012).

Hoffman, G. Evaluating fluency in human robot collaboration. IEEE Transactions on Human–Machine Systems 49, 209–218 (2019).

Scalera, L., Lozer, F., Giusti, A. & Gasparetto, A. An experimental evaluation of robot-stopping approaches for improving fluency in collaborative robotics. Robotica. 42, 1386–1402 (2024).

Hoffman, G. & Breazeal, C. Cost-based anticipatory action selection for human robot fluency. IEEE Transactions in Robotics 23, 952–961 (2007).

Rosenberger, P. et al. Object-independent human-to-robot handovers using real time robotic vision. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 6, 17–23 (2021).

Tsumugiwa, T., Yokogawa, R. & Hara, K. Variable impedance control with virtual stiffness for human–robot cooperative peg-in-hole task. In Proceedings of the 2002 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Vol. 2, 1075–1081 (2002).

Sirintuna, D., Giammarino, A. & Ajoudani, A. An object deformation-agnostic framework for human robot collaborative transportation. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 21, 1986–1999 (2024).

Ajoudani, A. et al. Progress and prospects of the human robot collaboration. Autonomous Robots 42, 957–975 (2018).

Ghonasgi, K., Higgins, T., Huber, M. E. & O Malley, M. K. Crucial hurdles to achieving human–robot harmony. Science Robotics. 9 (2024).

Khoramshahi, M. & Billard, A. A dynamical system approach to task-adaptation in physical human robot interaction. Autonomous Robots 43, 927–946 (2019).

Hadfield-Menell, D., Dragan, A., Abbeel, P. & Russell, S. Cooperative inverse reinforcement learning. In Proceedings of the 30th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 3916–3924 (2016).

Landi, C. T., Ferraguti, F., Sabattini, L., Secchi, C. & Fantuzzi, C. Admittance control parameter adaptation for physical human–robot interaction. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2911–2916 (2017).

Lamy, X., Colledani, F., Geffard, F., Measson, Y. & Morel, G. Achieving efficient and stable comanipulation through adaptation to changes in human arm impedance. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 265–271 (2009).

Lasota, P. A. & Shah, J. A. Analyzing the effects of human-aware motion planning on close-proximity human robot collaboration. Human Factors 57, 21–33 (2015).

Huggins, M. et al. Practical guidelines for intent recognition: BERT with minimal training data evaluated in real-world HRI application. In Proceedings of the 2021 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human–Robot Interaction (HRI), 341–350 (2021).

Franceschi, P., Pedrocchi, N. & Beschi, M. Identification of human control law during physical human robot interaction. Mechatronics 92, 102986 (2023).

Luo, J. et al. A physical human robot interaction framework for trajectory adaptation based on human motion prediction and adaptive impedance control. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 1–12 (2024).

Bobu, A., Peng, A., Agrawal, P., Shah, J. A. & Dragan, A. D. Aligning human and robot representations. In Proceedings of the 2024 ACM/IEEE International Conference on human–Robot Interaction (HRI), 42–54 (2024).

Ding, Y., Wilhelm, F., Faulhammer, L. & Thomas, U. With proximity servoing towards safe human–robot-interaction. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 4907–4912 (2019).

Nascimento, H., Mujica, M. & Benoussaad, M. Collision avoidance in human–robot interaction using kinect vision system combined with robot s model and data. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 10293–10298 (2020).

Liu, H. et al. Real-time and efficient collision avoidance planning approach for safe human–robot interaction. Journal of Intelligent and Robotic Systems 105, 93 (2022).

Ikeura, R., Moriguchi, T. & Mizutani, K. Optimal variable impedance control for a robot and its application to lifting an object with a human. In Proceedings of the 11th IEEE International Workshop on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 500–505 (2002).

Sadrfaridpour, B. & Wang, Y. Collaborative assembly in hybrid manufacturing cells: An integrated framework for human robot interaction. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 15, 1178–1192 (2018).

Losey, D. P. & O’Malley, M. K. Learning the correct robot trajectory in real-time from physical human interactions. Journal of Human-Robot Interaction 9, 1:1–1:19 (2019).

Cheng, X., Eden, J., Berret, B., Takagi, A. & Burdet, E. Interacting humans and robots can improve sensory prediction by adapting their viscoelasticity ArXiv:2410.13755 [cs] (2024).

Huber, M., Rickert, M., Knoll, A., Brandt, T. & Glasauer, S. human–robot interaction in handing-over tasks. In Proceeedings of the 17th IEEE International Symposium on Robot and Human Interactive Communication (RO-MAN), 107–112 (2008).

Zhao, G., Ahmad Sharbafi, M., Vlutters, M., van Asseldonk, E. & Seyfarth, A. Bio-inspired balance control assistance can reduce metabolic energy consumption in human walking. IEEE Transactions Neural Systems Rehabilitation Engineering 27, 1760–1769 (2019).

Glasauer, S., Huber, M., Basili, P., Knoll, A. & Brandt, T. Interacting in time and space: Investigating human–human and human–robot joint action. In 19th International Symposium in Robot and Human Interactive Communication, 252–257 (2010).

Maurice, P., Huber, M. E., Hogan, N. & Sternad, D. Velocity-curvature patterns limit human robot physical interaction. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters 3, 249–256 (2018).

Edraki, M., Maurice, P. & Sternad, D. Humans need augmented feedback to physically track non-biological robot movements. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 9872–9878 (2023).

Asadi, E., Li, B. & Chen, I.-M. Pictobot: A cooperative painting robot for interior finishing of industrial developments. IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine 25, 82–94 (2018).

Izawa, J., Rane, T., Donchin, O. & Shadmehr, R. Motor adaptation as a process of reoptimization. Journal of Neuroscience 28, 2883–2891 (2008).

Babic, J., Oztop, E. & Kawato, M. Human motor adaptation in whole body motion. Scientific Reports 6 (2016).

Lokesh, R. & Sternad, D. Human control of underactuated objects: adaptation to uncertain nonlinear dynamics ensures stability. In IEEE Transactions on Medical Robotics and Bionics , 1–1 (2024).

Ganesh, G. et al. Two is better than one: Physical interactions improve motor performance in humans. Scientific Reports 4, 3824 (2014).

Kato, S., Yamanobe, N., Venture, G., Yoshida, E. & Ganesh, G. The where of handovers by humans: Effect of partner characteristics, distance and visual feedback. PLoS ONE 14 (2019).

Takagi, A., Hirashima, M., Nozaki, D. & Burdet, E. Individuals physically interacting in a group rapidly coordinate their movement by estimating the collective goal. eLife 8, e41328 (2019).

Russo, M., Maselli, A., Sternad, D. & Pezzulo, G. Predictive Strategies for the Control of Complex Motor Skills: Recent Insights into Individual and Joint Actions. Current Opinions in Behavioral Sciences, 63, 101519 (2025).

Amirshirzad, N., Kumru, A. & Oztop, E. Human adaptation to human robot shared control. IEEE Transactions on Human–Machine Systems 49, 126–136 (2019).

Ikemoto, S., Amor, H. B., Minato, T., Jung, B. & Ishiguro, H. Physical human–robot interaction: Mutual learning and adaptation. IEEE Robotics and Automation Magazine 19, 24–35 (2012).

Nikolaidis, S., Hsu, D. & Srinivasa, S. human–robot mutual adaptation in collaborative tasks: Models and experiments. International Journal of Robotics Research 36, 618–634 (2017).

West, A. M. et al. Dynamic primitives limit human force regulation during motion. IEEE Robotics and Automation Letters (2022).

Linde, R. V. D. & Lammertse, P. HapticMaster a generic force controlled robot for human interaction. Industrial Robot: An International J 30, 515–524 (2003).

Lacquaniti, F., Terzuolo, C. & Viviani, P. The law relating the kinematic and figural aspects of drawing movements. Acta Psychologica 54, 115–130 (1983).

Viviani, P. & Schneider, R. A developmental study of the relationship between geometry and kinematics in drawing movements. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 17, 198–218 (1991).

Schaal, S. & Sternad, D. Origins and violations of the 2/3 power law in rhythmic three-dimensional arm movements. Experimental Brain Research 136, 60–72 (2001).

Karklinsky, M. et al. Robust human-inspired power law trajectories for humanoid HRP-2 robot. In Proceedings of the 6th IEEE International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), 106–113 (2016).

Tukey, J. The Problem of Multiple Comparisons. (Princeton University, 1953).

Pinheiro, J. et al. nlme: Linear and Nonlinear Mixed Effects Models (2024).

Fitts, P. The information capacity of the human motor system in controlling the amplitude of movement. Journal of Experimental Psychology (1954).

Schwartz, A. B. Direct cortical representation of drawing. Science 265, 540–542 (1994).

Gribble, P. L. & Ostry, D. J. Origins of the power law relation between movement velocity and curvature: modeling the effects of muscle mechanics and limb dynamics. Journal of Neurophysiology 76, 2853–2860 (1996).

Sternad, D. & Schaal, S. Segmentation of endpoint trajectories does not imply segmented control. Experimental Brain Research 124, 118–136 (1999).

Viviani, P. & Stucchi, N. Biological movements look uniform: Evidence of motor-perceptual interactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance 18, 603–623 (1992).

Feyzabadi, S. et al. Human force discrimination during active arm motion for force feedback design. IEEE Transactions on Haptics 6, 309–319 (2013).

Hermus, J., Doeringer, J., Sternad, D. & Hogan, N. Dynamic primitives in constrained action: systematic changes in the zero-force trajectory. Journal of Neurophysiology 131, 1–15 (2024).

Meier, B. & Cock, J. Offline consolidation in implicit sequence learning. Cortex 57, 156–166 (2014).

Crossman, E. R. F. W. A theory of the acquisition of speed-skill. Ergonomics 2, 153–166 (1959).

Park, S.-W., Dijkstra, T. & Sternad, D. Learning to never forget time scales and specificity of long-term memory of a motor skill. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 7 (2013).

Cohen, R. G. & Sternad, D. Variability in motor learning: relocating, channeling and reducing noise. Experimental Brain Research 193, 69–83 (2009).

Proctor, R. W. & Reeve, T. G. (eds) Stimulus-Response Compatibility: An Integrated Perspective (North-Holland, 1990).

Zhou, M., Jones, D., Schwaitzberg, S. & Cao, C. Role of haptic feedback and cognitive load in surgical skill acquisition. In Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, 51, 631–635 (2007).

Stepp, C. E., Dellon, B. T. & Matsuoka, Y. Contextual effects on robotic experiments of sensory feedback for object manipulation. In Proceedings of the 3rd IEEE RAS EMBS International Conference on Biomedical Robotics and Biomechatronics (BioRob), 58–63 (2010).

Nguyen, H.-N. & Lee, D. Hybrid force/motion control and internal dynamics of quadrotors for tool operation. In Proceedings of the 2013 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), 3458–3464 (2013).

De Luca, A. & Mattone, R. Sensorless robot collision detection and hybrid force/motion control. In Proceedings of the 2005 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 999–1004 (2005).

Ortenzi, V., Stolkin, R., Kuo, J. & Mistry, M. Hybrid motion/force control: A review. Advanced Robotics 31, 1102–1113 (2017).

Casadio, M., Pressman, A. & Mussa-Ivaldi, F. A. Learning to push and learning to move: the adaptive control of contact forces. Frontiers in Computational Neuroscience 9 (2015).

Mohebbi, A. Human–robot interaction in rehabilitation and assistance: a review. Current Robotics Report 1, 131–144 (2020).

Eden, J. et al. Principles of human movement augmentation and the challenges in making it a reality. Nature Communications 13, 1345 (2022).

Funding

This study was supported in part by the NIH-R37-HD087089 and NIH-R01-CRCNS-NS120579 grants awarded to D.S., and P.M. was supported by ANR-20-CE33-004.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.E., P.M., and D.S. contributed to the conception of the work and the design of the study; M.E. generated the data, prepared the figures, and drafted the manuscript. M.E. and H.S. analyzed the data. H.S., P.M., and D.S. contributed to the analysis and visualization. M.E., P.M., and D.S. finalized the writing of the manuscript. P.M. and D.S. secured research funding. M.E., H.S., P.M., and D.S. approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent

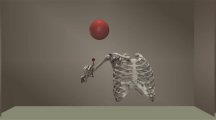

Informed consent was obtained from the first author, Mahdiar Edraki, for the publication of their photograph shown in Fig. 1B.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information 2.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Edraki, M., Serré, H., Maurice, P. et al. Force-velocity coupling limits human adaptation in physical human–robot interaction. Sci Rep (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34959-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-34959-4