Abstract

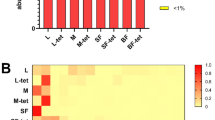

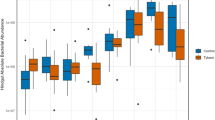

The sugar beet weevil is considered one of the most economically important insect pests in sugar beet cultivation. A promising biological control strategy involves the natural interaction between entomopathogenic fungi and arthropods. The successful application of M. brunneum as part of integrated biological control strategies against the sugar beet weevil has already been demonstrated resulting in lethal mycosis. However, the efficacy of this strain is affected by multiple factors. The intestinal microbiome of insects harbours beneficial microbes that possess various functions, such as defence mechanisms against insect-pathogens. Thus, investigating intestinal microbial interactions in combination with Metarhizium-application could reveal microbes that modulate susceptibility to pathogens. This study investigated whether intestinal microbial interactions influence mycosis caused by M. brunneum and M. robertsii. We analysed the intestinal microbiome of both treated and untreated sugar beet weevils, distinguishing between mycotic and non-mycotic individuals at the time of death. Notably, Pantoea and Enterobacter were significantly associated with mycotic individuals and may act as a potential antagonist to Metarhizium. In contrast, healthy individuals harboured diverse microbial communities that may provide a protective barrier against entomopathogens. However, the intestinal microbiome of non-mycotic specimens also comprised genera with presumed insecticidal properties, including Serratia, Penicillium and Cladosporium. The last two were also observed in the intestines of male individuals, which were generally at a higher risk of mortality. Further investigation is needed to confirm their insecticidal potential in the sugar beet weevil. A combined application could improve the efficacy of Metarhizium-based biocontrol, contributing to more sustainable pest management strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

The sequence data is available at NCBI and can be accessed with the BioProject accession number PRJNA1330021 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA1330021).

References

Chen, S., Zhang, C., Liu, J., Ni, H. & Wu, Z. Current status and prospects of the global sugar beet industry. Sugar Tech. 26, 1199–1207 (2024).

Oerke, E. C. & Dehne, H. W. Safeguarding production—losses in major crops and the role of crop protection. Crop Prot. 23, 275–285 (2004).

EPPO Global Database. Asproparthenis punctiventris (CLEOPU). https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/CLEOPU/distribution (2025).

Tielecke Biologie, Epidemiologie und Bekämpfung des Rübenderbrüßlers (Bothynoderes punctiventris Germ.). 2 (1952).

Drmić, Z. The sugar-beet Weevil (Bothynoderes Punctiventris Germar 1824., Col.: Curculionidae): Life cycle, Ecology and Area Wide Control by Mass Trapping (Agronomski fakultet, 2016).

Viric Gasparic, H., Lemic, D., Drmic, Z., Cacija, M. & Bazok, R. The efficacy of seed treatments on major sugar beet pests: possible consequences of the recent neonicotinoid ban. Agronomy 11, 1277 (2021).

Harvey, J. A. et al. Scientists’ warning on climate change and insects. Ecol. Monogr. 93, e1553 (2023).

Maienfisch, P., Brandl, F., Kobel, W., Rindlisbacher, A. & Senn, R. CGA 293’343: A Novel, Broad-Spectrum neonicotinoid insecticide. in Nicotinoid Insecticides and the Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor (eds Yamamoto, I. & Casida, J. E.) 177–209 (Springer Japan, Tokyo, doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-4-431-67933-2_8. (1999).

Health, E. U. and Food Safety. Neonicotinoids. (2023).

Lacey, L. A. et al. Insect pathogens as biological control agents: Back to the future. jip https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jip.2015.07.009 (2015).

Mantzoukas, S., Kitsiou, F., Natsiopoulos, D. & Eliopoulos, P. A. Entomopathogenic fungi: interactions and applications. Encyclopedia 2, 646–656 (2022).

Wang, Y., Han, L., Xia, Y. & Xie, J. The entomopathogenic fungus metarhizium anisopliae affects feeding preference of Sogatella furcifera and its potential targets’ identification. JoF 8, 506 (2022).

Khoja, S. et al. Volatiles of the entomopathogenic fungus, metarhizium brunneum, attract and kill plant parasitic nematodes. Biol. Control. 152, 104472 (2021).

Bai, J. et al. Analysis of intestinal microbial diversity of four species of grasshoppers and determination of cellulose digestibility. Insects 13, 432 (2022).

Zottele, M. et al. Integrated Biological Control of the Sugar Beet Weevil Asproparthenis punctiventris with the Fungus Metarhizium brunneum: New Application Approaches. Pathogens 12, 99 (2023).

Ahmad, I., Jiménez-Gasco, M. D. M., Luthe, D. S., Shakeel, S. N. & Barbercheck, M. E. Endophytic metarhizium Robertsii promotes maize growth, suppresses insect growth, and alters plant defense gene expression. Biol. Control. 144, 104167 (2020).

Islam, W., Noman, A., Naveed, H., Huang, Z. & Chen, H. Y. H. Role of environmental factors in shaping the soil Microbiome. Environ. Sci. Pollut Res. 27, 41225–41247 (2020).

Zhang, Y., Zhang, S. & Xu, L. The pivotal roles of gut microbiota in insect plant interactions for sustainable pest management. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 9, 66 (2023).

Zhang, W. et al. Cross-talk between immunity and behavior: insights from entomopathogenic fungi and their insect hosts. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 48, fuae003 (2024).

Engel, P. & Moran, N. A. The gut microbiota of insects – diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 37, 699–735 (2013).

St. Leger, R. J. The evolution of complex Metarhizium-insect-plant interactions. Fungal Biology. 128, 2513–2528 (2024).

Kryukov, V. Y. et al. Fungus metarhizium Robertsii and neurotoxic insecticide affect gut immunity and microbiota in Colorado potato beetles. Sci. Rep. 11, 1299 (2021).

Kabaluk, T., Li-Leger, E. & Nam, S. Metarhizium brunneum – An enzootic wireworm disease and evidence for its suppression by bacterial symbionts. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 150, 82–87 (2017).

Hassani, M. A., Durán, P. & Hacquard, S. Microbial interactions within the plant holobiont. Microbiome 6, 58 (2018).

Compant, S. et al. Harnessing the plant Microbiome for sustainable crop production. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-024-01079-1 (2024).

Pyatnitzkiï, G. K. Ecological basis of the control measures against the beet weevil on old beet fields. in Summary of the scientific research work of the institute of Plant protection for the year 1939 (Lenin Acad. agric Sci., 1940).

Drmić, Z., Čačija, M., Virić Gašparić, H., Lemić, D. & Bažok, R. Phenology of the sugar beet weevil, Bothynoderes punctiventris germar (Coleoptera: Curculionidae), in Croatia. Bull. Entomol. Res. 109, 518–527 (2019).

European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) et al. Peer review of the pesticide risk assessment of the active substance Metarhizium brunneum BIPESCO 5/F52. EFS2 18 et al. (2020).

Zottele, M. et al. Biological diabrotica management and monitoring of metarhizium diversity in Austrian maize fields following mass application of the entomopathogen metarhizium brunneum. Appl. Sci. 11, 9445 (2021).

Wöber, D. et al. The role of microbial communities in maintaining post-harvest sugar beet storability. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 222, 113401 (2025).

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat. Methods. 9, 357–359 (2012).

Andrews, S. FastQC: a quality control tool for high throughput sequence data. (2010).

Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. (2011).

Callahan, B. J. et al. DADA2: High-resolution sample inference from illumina amplicon data. Nat. Methods. 13, 581–583 (2016).

Rivers, A. R., Weber, K. C., Gardner, T. G., Liu, S. & Armstrong, S. D. ITSxpress: software to rapidly trim internally transcribed spacer sequences with quality scores for marker gene analysis. F1000Res 7, 1418 (2018).

Quast, C. et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, D590–D596 (2012).

Nilsson, R. H. et al. The UNITE database for molecular identification of fungi: handling dark taxa and parallel taxonomic classifications. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, D259–D264 (2019).

R Core Team. A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2022).

Linz, A. M. et al. Bacterial Community Composition and Dynamics Spanning Five Years in Freshwater Bog Lakes. mSphere 2, e00169-17 (2017).

Saary, P., Forslund, K., Bork, P. & Hildebrand, F. RTK: efficient rarefaction analysis of large datasets. Bioinformatics 33, 2594–2595 (2017).

IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (IBM Corp, 2019).

Allignol, A. & Latouche, A. C. R. A. N. Task View: Survival Analysis. (2025).

Kassambara, A., Marcin, K. & Przemyslaw, B. survminer: Drawing Survival Curves using ‘ggplot2’. (2025).

Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis. (2016).

Lathi, L. & Shetty, S. (2012). microbiome R package.

Oksanen, J. et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. 2.6–6.1 https://doi.org/10.32614/CRAN.package.vegan (2001).

Hubert, M., Reynkens, T., Schmitt, E. & Verdonck, T. Sparse PCA for High-Dimensional data with outliers. Technometrics 58, 424–434 (2016).

McMurdie, P. J. & Holmes, S. Phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of Microbiome census data. PLoS ONE. 8, e61217 (2013).

Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 15, 550 (2014).

Gu, Z., Eils, R. & Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 32, 2847–2849 (2016).

Mallick, H. et al. Multivariable association discovery in population-scale meta-omics studies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 17, e1009442 (2021).

Foster, Z. S. L., Sharpton, T. J., Grünwald, N. J. & Metacoder An R package for visualization and manipulation of community taxonomic diversity data. PLoS Comput. Biol. 13, e1005404 (2017).

Jarmer, L. Auftreten des Rübenderbrüsslers (Asproparthenis punctiventris) in Ostösterreich unter besonderer Berücksichtigung von Witterungsverhältnissen. Master thesis (2022).

Stenberg, J. A. et al. When is it biological control? A framework of definitions, mechanisms, and classifications. J. Pest Sci. 94, 665–676 (2021).

Lou, Y., Wang, G., Zhang, W. & Xu, L. Adaptation strategies of insects to their environment by collecting and utilizing external microorganisms. Integr. Zool. 20, 208–212 (2025).

Dittmann, L., Spangl, B. & Koschier, E. H. Suitability of amaranthaceae and Polygonaceae species as food source for the sugar beet weevil asproparthenis punctiventris germar. J. Plant. Dis. Prot. 130, 67–75 (2023).

Keller, S. & Zimmermann, G. Mycopathogens of Soil Insects. (Academic, 1989).

Zhang, W. et al. Unlocking agro-ecosystem sustainability: exploring the bottom‐up effects of microbes, plants, and insect herbivores. Integr. Zool. 20, 465–484 (2025).

Mondal, S., Somani, J., Roy, S., Babu, A. & Pandey, A. K. Insect microbial symbionts: Ecology, Interactions, and biological significance. Microorganisms 11, 2665 (2023).

Yasika, Y. & Shivakumar, M. S. A comprehensive account of functional role of insect gut Microbiome in insect orders. J. Nat. Pesticide Res. 11, 100110 (2025).

Peral-Aranega, E. et al. New insight into the bark beetle Ips typographus bacteriome reveals unexplored diversity potentially beneficial to the host. Environ. Microbiome. 18, 53 (2023).

Lähn, K., Wolf, G., Ulrich-Eberius, C. & Koch, E. Cultural characteristics and in vitro antagonistic activity of two isolates of Mortierella alpina peyronel / Kulturmerkmale und in vitro antagonistische Aktivität Zweier isolate von Mortierella alpina peyronel. Z. für Pflanzenkrankheiten Und Pflanzenschutz / J. Plant. Dis. Prot. 109, 166–179 (2002).

DiLegge, M. J., Manter, D. K. & Vivanco, J. M. A novel approach to determine generalist nematophagous microbes reveals Mortierella globalpina as a new biocontrol agent against meloidogyne spp. Nematodes. Sci. Rep. 9, 7521 (2019).

Sacristán-Pérez-Minayo, G., López-Robles, D. J. & Rad, C. Miranda-Barroso, L. Microbial inoculation for productivity improvements and potential biological control in sugar beet crops. Front. Plant. Sci. 11, 604898 (2020).

Berg, G. et al. Plant microbial diversity is suggested as the key to future biocontrol and health trends. FEMS Microbiol. Ecology 93, fix050 (2017).

The Human Microbiome Project Consortium. Structure, function and diversity of the healthy human Microbiome. Nature 486, 207–214 (2012).

Fierer, N., Wood, S. A. & De Bueno, C. P. How microbes can, and cannot, be used to assess soil health. Soil Biol. Biochem. 153, 108111 (2021).

Hummadi, E. H. et al. Antimicrobial volatiles of the insect pathogen metarhizium brunneum. JoF 8, 326 (2022).

Landry, M., Comeau, A. M., Derome, N., Cusson, M. & Levesque, R. C. Composition of the Spruce budworm (Choristoneura fumiferana) midgut microbiota as affected by rearing conditions. PLoS ONE. 10, e0144077 (2015).

Dillon, R. J. & Charnley, A. K. Chemical barriers to gut infection in the desert locust: in vivo production of antimicrobial phenols associated with the bacterium Pantoea agglomerans. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 66, 72–75 (1995).

Aw, K. M. S. & Hue, S. M. Mode of infection of metarhizium spp. Fungus and their potential as biological control agents. JoF 3, 30 (2017).

Vasseur-Coronado, M. et al. Ecological role of volatile organic compounds emitted by Pantoea agglomerans as interspecies and interkingdom signals. Microorganisms 9, 1186 (2021).

Brancini, G. T. P., Hallsworth, J. E., Corrochano, L. M. & Braga, G. Ú. L. Photobiology of the keystone genus metarhizium. J. Photochem. Photobiol., B. 226, 112374 (2022).

Nicoletti, R., Andolfi, A., Becchimanzi, A. & Salvatore, M. M. Anti-Insect properties of penicillium secondary metabolites. Microorganisms 11, 1302 (2023).

Yin, G. et al. Genomic analyses of penicillium species have revealed patulin and citrinin gene clusters and novel loci involved in Oxylipin production. JoF 7, 743 (2021).

Nicoletti, R., Russo, E. & Becchimanzi, A. Cladosporium—Insect Relationships JoF 10, 78 (2024).

Quiroz-Castañeda, R. E. et al. Identification of a new Alcaligenes faecalis strain MOR02 and assessment of its toxicity and pathogenicity to insects. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 1–10 (2015).

Tang, X., Wang, X., Cheng, X., Wang, X. & Fang, W. Metarhizium fungi as plant symbionts. New Plant Prot. 2, e23 (2025).

Flyg, C. & Xanthopoulos, K. G. Insect pathogenic properties of Serratia Marcescens. Passive and active resistance to insect immunity studied with Protease-Deficient and Phage-Resistant mutants. Microbiology 129, 453–464 (1983).

Tao, A. et al. Characterization of a novel chitinolytic Serratia marcescens strain TC-1 with broad insecticidal spectrum. AMB Expr. 12, 100 (2022).

Akhtar, M. R., Younas, M. & Xia, X. Pathogenicity of Serratia marcescens strains as biological control agent: implications for sustainable pest management. Insect Sci. 1744-7917 (13489). https://doi.org/10.1111/1744-7917.13489 (2025).

Barman, S. & Bhattacharya, S. S. & Chandra Mandal, N. Serratia. in Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology 27–36 (Academic Press, 2020). https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-823414-3.00003-4

Hopkins, B. R. & Kopp, A. Evolution of sexual development and sexual dimorphism in insects. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 69, 129–139 (2021).

Cordeschi, G., Canestrelli, D. & Porretta, D. Sex-biased phenotypic plasticity affects sexual dimorphism patterns under changing environmental conditions. Sci. Rep. 14, 892 (2024).

Belmonte, R. L., Corbally, M. K., Duneau, D. F. & Regan, J. C. Sexual dimorphisms in innate immunity and responses to infection in drosophila melanogaster. Front. Immunol. 10, 3075 (2020).

Teder, T., Kaasik, A., Taits, K. & Tammaru, T. Why do males emerge before females? Sexual size dimorphism drives sexual bimaturism in insects. Biol. Rev. 96, 2461–2475 (2021).

Singer, M. C. Sexual selection for small size in male butterflies. Am. Nat. 119, 440–443 (1982).

Zonneveld, C. Being big or emerging early? Polyandry and the Trade-Off between size and emergence in male butterflies. Am. Nat. 147, 946–965 (1996).

Liao, A., Cavigliasso, F., Savary, L. & Kawecki, T. J. Effects of an entomopathogenic fungus on the reproductive potential of Drosophila males. Ecol. Evol. 14, e11242 (2024).

Drmić, Z. et al. Area-wide mass trapping by pheromone‐based attractants for the control of sugar beet weevil (Bothynoderes punctiventris Germar, coleoptera: Curculionidae). Pest Manag. Sci. 73, 2174–2183 (2017).

Koschier, E. H., Dittmann, L. & Spangl, B. Olfactory responses of asproparthenis punctiventris germar to leaf odours of amaranthaceae plants. Insects 15, 297 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Martina Dokal and Marion Seiter from AGRANA Research & Innovation Center GmbH (Austria) for providing us with weevil samples. Our thanks also go to Maria Zottele and Hermann Strasser of the University of Innsbruck (Austria) for their valuable support and expertise in shaping this work, which has been financially supported by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Climate and Environmental Protection, Regions and Water Management of the Republic of Austria (Project Nr. 101749).

Funding

This study has been financially supported by the Federal Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Climate and Environmental Protection, Regions and Water Management of the Republic of Austria (Project Nr. 101749).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EMM developed and supervised the project. MW and KW designed the bioassays. MW, KW and SM conducted the experiments. MW and SM performed the statistical analysis of the bioassay. KHH prepared the microbial data, including DNA extraction, quality control and sequencing. DW and FC analysed the microbiome. DW visualised and interpreted the data. DW drafted the manuscript. EMM interpreted the data and revised the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wöber, D., Wernicke, M., Cerqueira, F. et al. Intestinal microbiome interactions influence Metarhizium-based biocontrol efficacy against the sugar beet weevil. Sci Rep (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36038-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36038-8