Abstract

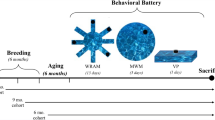

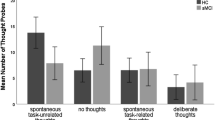

Spatial pattern separation (SPS) is a memory process that enables the discrimination of similar spatial locations. This process is vulnerable to pathophysiological changes in the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but the translational potential of its testing remains unclear. This study aimed to evaluate the potential of SPS testing as a translational cognitive marker for identifying early AD and enabling direct comparisons of cognitive outcomes in animals and humans. We used a validated SPS task to examine biomarker-defined participants with amnestic mild cognitive impairment due to AD (AD aMCI; n = 56) and cognitively normal (CN) participants (n = 60). An animal version of this task, based on a modified Morris Water Maze task, was used to test six-month-old transgenic TgF344-AD rats (n = 38) and wild-type (WT) rats (n = 36). AD aMCI participants performed worse than CN participants, with performance declining as distance decreased. These results remained unchanged when adjusted for memory performance. TgF344-AD rats performed worse than WT rats in a probe trial with a 90° SPS design, but not in probe trials with an 180° SPS design or no SPS demands. The discriminatory power of the task was similar in the human and animal experiments. The findings demonstrate comparable SPS deficits in the early stages of AD in both humans and rodent models, which are not attributable to general memory impairment. SPS testing enables direct comparisons to be made between the cognitive performance of rats and humans, making it a promising approach for translational AD research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

All primary data from this study are detailed within the article. Any additional information and dataset required to reanalyse the data reported in this paper are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alzheimers Dement. 20, 3708–3821. https://doi.org/10.1002/ALZ.13809 (2024).

Cummings, J. et al. Alzheimer’s disease drug development pipeline: 2023. Alzheimers Dement. Transl Res. Clin. Interv. 9, e12385. https://doi.org/10.1002/TRC2.12385 (2023).

Sims, J. R. et al. Donanemab in early symptomatic Alzheimer disease: the TRAILBLAZER-ALZ 2 randomized clinical trial. JAMA 330, 512–527. https://doi.org/10.1001/JAMA.2023.13239 (2023).

van Dyck, C. et al. Lecanemab in early Alzheimer’s disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 388, 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2212948 (2023).

Laczó, J. et al. Scopolamine disrupts place navigation in rats and humans: a translational validation of the Hidden Goal Task in the Morris water maze and a real maze for humans. Psychopharmacol. (Berl). 234, 535–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00213-016-4488-2 (2017).

Hort, J. et al. Effect of donepezil in Alzheimer disease can be measured by a computerized human analog of the Morris water maze. Neurodegener. Dis. 13, 192–196. https://doi.org/10.1159/000355517 (2014).

Guo, H. B. et al. Donepezil improves learning and memory deficits in APP/PS1 mice by inhibition of microglial activation. Neuroscience 290, 530–542. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.01.058 (2015).

Knierim, J. J. & Neunuebel, J. P. Tracking the flow of hippocampal computation: pattern separation, pattern completion, and attractor dynamics. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 129, 38–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NLM.2015.10.008 (2016).

Braak, H. & Braak, E. Staging of Alzheimer’s disease-related neurofibrillary changes. Neurobiol. Aging 16, 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-4580(95)00021-6 (1995).

Yassa, M. A. & Stark, C. E. L. Pattern separation in the hippocampus. Trends Neurosci. 34, 515–525. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TINS.2011.06.006 (2011).

Leal, S. L. & Yassa, M. A. Integrating new findings and examining clinical applications of pattern separation. Nat. Neurosci. 21, 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-017-0065-1 (2018).

Hunsaker, M. R. & Kesner, R. P. The operation of pattern separation and pattern completion processes associated with different attributes or domains of memory. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 37, 36–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUBIOREV.2012.09.014 (2013).

Bennett, I. J. & Stark, C. E. L. Mnemonic discrimination relates to perforant path integrity: An ultra-high resolution diffusion tensor imaging study. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 129, 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NLM.2015.06.014 (2016).

Giocomo, L. M. & Hasselmo, M. E. Neuromodulation by glutamate and acetylcholine can change circuit dynamics by regulating the relative influence of afferent input and excitatory feedback. Mol. Neurobiol. 36, 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12035-007-0032-Z (2007).

Clewett, D., Huang, R. & Davachi, L. Locus coeruleus activation resets hippocampal event representations and separates adjacent memories. Neuron 113, 2521–2535.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEURON.2025.05.013 (2025).

Sassin, I. et al. Evolution of Alzheimer’s disease-related cytoskeletal changes in the basal nucleus of Meynert. Acta Neuropathol. 100, 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/S004019900178 (2000).

Geula, C. et al. Cholinergic neuronal and axonal abnormalities are present early in aging and in Alzheimer disease. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 67, 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1097/NEN.0B013E31816A1DF3 (2008).

Schmitz, T. W. & Nathan Spreng, R. Basal forebrain degeneration precedes and predicts the cortical spread of Alzheimer’s pathology. Nat. Commun. 7, 13249. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms13249 (2016).

Gilbert, P. E. & Kesner, R. P. Role of the rodent hippocampus in paired-associate learning involving associations between a stimulus and a spatial location. Behav. Neurosci. 116, 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1037//0735-7044.116.1.63 (2002).

Ikonen, S. et al. Cholinergic system regulation of spatial representation by the hippocampus. Hippocampus 12, 386–397. https://doi.org/10.1002/hipo.1109 (2002).

Parizkova, M. et al. Spatial pattern separation in early Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 76, 121–138. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-200093 (2020).

Segal, S. K. et al. Norepinephrine-mediated emotional arousal facilitates subsequent pattern separation. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 97, 465–469. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NLM.2012.03.010 (2012).

Laczó, M. et al. Spatial pattern separation testing differentiates Alzheimer’s disease biomarker-positive and biomarker-negative older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 13, 774600. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnagi.2021.774600 (2021).

Cohen, R. M. et al. A transgenic Alzheimer rat with plaques, tau pathology, behavioral impairment, oligomeric Aβ, and frank neuronal loss. J. Neurosci. 33, 6245–6256. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3672-12.2013 (2013).

Sheardova, K. et al. Czech Brain Aging Study (CBAS): prospective multicentre cohort study on risk and protective factors for dementia in the Czech Republic. BMJ Open 9, e030379. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJOPEN-2019-030379 (2019).

Laczó, M. et al. Different profiles of spatial navigation deficits in Alzheimer’s disease biomarker-positive versus biomarker-negative older adults with amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14, 886778. https://doi.org/10.3389/FNAGI.2022.886778/XML (2022).

Albert, M. S. et al. The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 7, 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.JALZ.2011.03.008 (2011).

Laczó, M. et al. Spatial navigation deficits in early Alzheimer’s disease: the role of biomarkers and APOE genotype. J. Neurol. 272, 438. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00415-025-13151-8 (2025).

Holden, H. M. et al. Spatial pattern separation in cognitively normal young and older adults. Hippocampus 22, 1826–1832. https://doi.org/10.1002/HIPO.22017 (2012).

Bezdicek, O. et al. Czech version of Rey Auditory Verbal Learning test: normative data. Aging Neuropsychol. Cogn. 21, 693–721. https://doi.org/10.1080/13825585.2013.865699 (2014).

Nikolai, T. et al. The Uniform Data Set, Czech version: normative data in older adults from an international perspective. J. Alzheimers Dis. 61, 1233–1240. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-170595 (2018).

Drozdová, K. et al. Normative data for the Rey‑ Osterrieth Complex Figure Test in older Czech adults. Ces. Slov. Neurol. Neurochir. 78, 542–549 (2015).

Mazancova, A. F. et al. The reliability of clock drawing test scoring systems modeled on the normative data in healthy aging and nonamnestic mild cognitive impairment. Assessment 24, 945–957. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191116632586 (2017).

Bezdicek, O. et al. Czech version of the Trail Making Test: normative data and clinical utility. Arch. Clin. Neuropsychol. 27, 906–914. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acs084 (2012).

Nikolai, T. et al. Verbal fluency tests – Czech normative study for older persons. Ces. Slov. Neurol. Neurochir. 78, 292–299. https://doi.org/10.14735/AMCSNN2015292 (2015).

Zemanova, N. et al. Validity study of the Boston Naming Test Czech version. Ces. Slov. Neurol. Neurochir. 79, 307–316. https://doi.org/10.14735/amcsnn2016307 (2016).

Sheikh, J. I. & Yesavage, J. A. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin. Gerontol. 5, 165–173. https://doi.org/10.1300/j018v05n01_09 (1986).

Beck, A. T. et al. An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: psychometric properties. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 56, 893–897. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893 (1988).

Vanderstichele, H. et al. Standardization of preanalytical aspects of cerebrospinal fluid biomarker testing for alzheimer’s disease diagnosis: A consensus paper from the Alzheimer’s Biomarkers Standardization Initiative. Alzheimers Dement. 8, 65–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2011.07.004 (2012).

Cerman, J. et al. Cerebrospinal fluid ratio of phosphorylated tau protein and beta amyloid predicts amyloid PET positivity. Ces. Slov. Neurol. Neurochir. 83, 173–179. https://doi.org/10.14735/AMCSNN2020173 (2020).

Matuskova, V. et al. Mild behavioral impairment in early alzheimer’s disease and its association with APOE and BDNF risk genetic polymorphisms. Alzheimers Res. Ther. 16, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13195-024-01386-Y (2024).

Belohlavek, O. et al. Improved beta-amyloid PET reproducibility using two-phase acquisition and grey matter delineation. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging. 46, 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00259-018-4140-y (2019).

Laczó, J. et al. The effect of TOMM40 on spatial navigation in amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol. Aging. 36, 2024–2033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2015.03.004 (2015).

Ashburner, J. Computational anatomy with the SPM software. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 27, 1163–1174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mri.2009.01.006 (2009).

Teipel, S. J. et al. Measurement of basal forebrain atrophy in Alzheimer’s disease using MRI. Brain 128, 2626–2644. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awh589 (2005).

Teipel, S. J. et al. Brain atrophy in primary progressive aphasia involves the cholinergic basal forebrain and Ayala’s nucleus. Psychiatry Res. 221, 187–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PSCYCHRESNS.2013.10.003 (2014).

Wolf, D. et al. Association of basal forebrain volumes and cognition in normal aging. Neuropsychologia 53, 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2013.11.002 (2014).

Parizkova, M. et al. The effect of Alzheimer’s disease on spatial navigation strategies. Neurobiol. Aging. 64, 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.12.019 (2018).

Ashburner, J. A fast diffeomorphic image registration algorithm. Neuroimage 38, 95–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.007 (2007).

Kondo, H. & Zaborszky, L. Topographic organization of the basal forebrain projections to the perirhinal, postrhinal, and entorhinal cortex in rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 524, 2503–2515. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.23967 (2016).

Jack, C. R. et al. MR-based hippocampal volumetry in the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurology 42, 183–183. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.42.1.183 (1992).

Nataraj, A., Blahna, K. & Jezek, K. Insights from TgF344-AD, a double transgenic rat model in Alzheimer’s disease research. Physiol. Res. 74, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.33549/physiolres.935464 (2025).

Sone, K. et al. Changes of estrous cycles with aging in female F344/n rats. Exp. Anim. 56, 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1538/expanim.56.139 (2007).

Becegato, M. et al. Impaired discriminative avoidance and increased plasma corticosterone levels induced by vaginal lavage procedure in rats. Physiol. Behav. 232, 113343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2021.113343 (2021).

Maei, H. R. et al. What is the most sensitive measure of water maze probe test performance? Front. Integr. Neurosci. 3, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/neuro.07.004.2009 (2009).

Lee, A. C. H., Scahill, V. L. & Graham, K. S. Activating the medial temporal lobe during oddity judgment for faces and scenes. Cereb. Cortex 18, 683–696. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhm104 (2008).

Berron, D. et al. Age-related functional changes in domain-specific medial temporal lobe pathways. Neurobiol. Aging 65, 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.12.030 (2018).

Mesulam, M. et al. Cholinergic innervation of cortex by the basal forebrain: cytochemistry and cortical connections of the septal area, diagonal band nuclei, nucleus basalis (substantia innominata), and hypothalamus in the rhesus monkey. J. Comp. Neurol. 214, 170–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/cne.902140206 (1983).

Webb, C. E. et al. Beta-amyloid burden predicts poorer mnemonic discrimination in cognitively normal older adults. Neuroimage 221, 117199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117199 (2020).

Maass, A. et al. Alzheimer’s pathology targets distinct memory networks in the ageing brain. Brain 142, 2492–2509. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awz154 (2019).

Thal, D. R. et al. Phases of Aβ-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 58, 1791–1800. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.58.12.1791 (2002).

Sanchez, J. S. et al. The cortical origin and initial spread of medial temporal tauopathy in Alzheimer’s disease assessed with positron emission tomography. Sci. Transl. Med. 13, eabc0655. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abc0655 (2021).

Huijbers, W. et al. Amyloid deposition is linked to aberrant entorhinal activity among cognitively normal older adults. J. Neurosci. 34, 5200–5210. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3579-13.2014 (2014).

Adams, J. N. et al. Entorhinal–hippocampal circuit integrity is related to mnemonic discrimination and amyloid-β pathology in older adults. J. Neurosci. 42, 8742–8753. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.1165-22.2022 (2022).

Marks, S. M. et al. Tau and β-amyloid are associated with medial temporal lobe structure, function, and memory encoding in normal aging. J. Neurosci. 37, 3192–3201. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.3769-16.2017 (2017).

Fernández-Cabello, S. et al. Basal forebrain volume reliably predicts the cortical spread of Alzheimer’s degeneration. Brain 143, 993–1009. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awaa012 (2020).

Braak, H. & Del Tredici, K. The pathological process underlying Alzheimer’s disease in individuals under thirty. Acta Neuropathol. 121, 171–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00401-010-0789-4 (2010).

Theofilas, P. et al. Locus coeruleus volume and cell population changes during Alzheimer’s disease progression: A stereological study in human postmortem brains with potential implication for early-stage biomarker discovery. Alzheimers Dement. 13, 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2016.06.2362 (2017).

Swanson, L. W., Köhler, C. & Björklund, A. The limbic region. I: The septohippocampal system. Handb. Chem. Neuroanat. 5, 125–277 (1987).

Walling, S. G. & Harley, C. W. Locus ceruleus activation initiates delayed synaptic potentiation of perforant path input to the dentate gyrus in awake rats: a novel beta-adrenergic- and protein synthesis-dependent mammalian plasticity mechanism. J. Neurosci. 24, 598–604. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4426-03.2004 (2004).

Gephine, L. et al. Vulnerability of spatial pattern separation in 5xFAD Alzheimer’s disease mouse model. J. Alzheimers Dis. 97, 1889–1900. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-231112 (2024).

Zhu, H. et al. Impairments of spatial memory in an Alzheimer’s disease model via degeneration of hippocampal cholinergic synapses. Nat. Commun. 8, 1676. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01943-0 (2017).

Herbeaux, K. et al. Passive immunization against amyloid peptide restores pattern separation deficits in early stage of amyloid pathology but not in normal aging. Explor. Neuroprotective Ther. 5, 1004108. https://doi.org/10.37349/ENT.2025.1004108 (2025).

Kim, K. R. et al. Impaired pattern separation in Tg2576 mice is associated with hyperexcitable dentate gyrus caused by Kv4.1 downregulation. Mol. Brain 14, 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13041-021-00774-x (2021).

Gilbert, P. E., Kesner, R. P. & Decoteau, W. E. Memory for spatial location: role of the hippocampus in mediating spatial pattern separation. J. Neurosci. 18, 804–810. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-02-00804.1998 (1998).

McTighe, S. M. et al. A new touchscreen test of pattern separation: effect of hippocampal lesions. Neuroreport 20, 881–885. https://doi.org/10.1097/WNR.0B013E32832C5EB2 (2009).

Berkowitz, L. E. et al. Progressive impairment of directional and spatially precise trajectories by TgF344-Alzheimer’s disease rats in the Morris water task. Sci. Rep. 8, 16153. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41598-018-34368-W (2018).

Rorabaugh, J. M. et al. Chemogenetic locus coeruleus activation restores reversal learning in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 140, 3023–3038. https://doi.org/10.1093/BRAIN/AWX232 (2017).

Izquierdo, A. et al. The neural basis of reversal learning: An updated perspective. Neuroscience 345, 12–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.03.021 (2017).

Kelberman, M. A. et al. Consequences of hyperphosphorylated tau in the locus coeruleus on behavior and cognition in a rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. J. Alzheimers Dis. 86, 1037–1059. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-215546 (2022).

Kelberman, M. A. et al. Age-dependent dysregulation of locus coeruleus firing in a transgenic rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 125, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2023.01.016 (2023).

Saucier, D. M. et al. Sex differences in object location memory and spatial navigation in Long-Evans rats. Anim. Cogn. 11, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-007-0096-1/metrics (2008).

Zorzo, C., Arias, J. L. & Méndez, M. Are there sex differences in spatial reference memory in the Morris water maze? A large-sample experimental study. Learn. Behav. 52, 179–190. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13420-023-00598-w (2024).

Yagi, S. et al. Sex and strategy use matters for pattern separation, adult neurogenesis, and immediate early gene expression in the hippocampus. Hippocampus 26, 87–101. https://doi.org/10.1002/HIPO.22493 (2016).

Rodríguez, C. A., Agulair, R. & Chamizo, V. D. Landmark learning in a navigation task is not affected by the female rats’ estrus cycle. Psicológica 32, 279–299 (2011).

Shinohara, M. et al. Regional distribution of synaptic markers and APP correlate with distinct clinicopathological features in sporadic and familial Alzheimer’s disease. Brain 137, 1533–1549. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awu046 (2014).

Roher, A. E., Maarouf, C. L. & Kokjohn, T. A. Familial presenilin mutations and sporadic Alzheimer’s disease pathology: Is the assumption of biochemical equivalence justified? J. Alzheimers Dis. 50, 645–658. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-150757 (2016).

Bac, B. et al. The TgF344-AD rat: behavioral and proteomic changes associated with aging and protein expression in a transgenic rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol. Aging 123, 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.NEUROBIOLAGING.2022.12.015 (2023).

Goodman, A. M. et al. Heightened hippocampal β-adrenergic receptor function drives synaptic potentiation and supports learning and memory in the TgF344-AD rat model during prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. J. Neurosci. 41, 5747–5761. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0119-21.2021 (2021).

Smith, L. A., Goodman, A. M. & McMahon, L. L. Dentate granule cells are hyperexcitable in the TgF344-AD rat model of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Synaptic Neurosci. 14, 826601. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2022.826601 (2022).

Berg, M. et al. Partial normalization of hippocampal oscillatory activity during sleep in TgF344-AD rats coincides with increased cholinergic synapses at early-plaque stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 13, 96. https://doi.org/10.1186/S40478-025-02016-W (2025).

Fowler, C. F. et al. Neurochemical and cognitive changes precede structural abnormalities in the TgF344-AD rat model. Brain Commun. 4, fcac072. https://doi.org/10.1093/BRAINCOMMS/FCAC072 (2022).

Polis, B. & Samson, A. O. Addressing the discrepancies between animal models and human Alzheimer’s disease pathology: implications for translational research. J. Alzheimers Dis. 98, 1199–1218. https://doi.org/10.3233/JAD-240058 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms M. Dokoupilova, Ms R. Svatkova, Ms V. Sedlakova, Ms N. Daniskova, Ms Z. Svacova, Dr H. Horakova, Dr V. Matuskova, Dr K. Veverova, Ms A. Katonova, Ms V. Jurasova, and Dr T. Nikolai for help with data collection; Dr J. Cerman, Dr I. Trubacik Mokrisova, and Dr J. Novakova Martinkova for help with participant recruitment; Mrs M. Radostova and Mrs V. Markova for technical support.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute for Neurological Research (Programme EXCELES, ID Project No. LX22NPO5107) – Funded by the European Union – Next Generation EU (ML, KM, NK, MV, JH, AS, JS, JL), Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic — conceptual development of research organization, University Hospital Motol, Prague, Czech Republic grant nr. 00064203 (ML, MV, JH, JL), the Institutional Support of Excellence 3 2. LF UK (Grant No. 6980382) (ML, JL, JH), Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic, grant nr. NW25-04-00337 (ML, JL), the Grant Agency of Charles University (Grant No. 40125) (ML), the Czech Science Foundation (GACR) registration number 22–33968S (ML, SB, MV, JH, JL) and 21–16667K (AS), Alzheimer’s Foundation (ML), and Martina Roeselová Memorial Fellowship (ML).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ML, KM, AS, JS and JL designed the study, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. ML, KM, and JL analysed the data. NK and SB collected and interpreted the data, and critically reviewed the manuscript. JH and MV provided funding and critically reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

JH is a medical advisor at Neurona lab, Terrapino mobile app, consulted for Eisai, Eli Lilly, Biogen, Schwabe, and holds stock options in Alzheon. Other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

In the human study, all participants provided written informed consent, and the study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Motol University Hospital (consent number EK701/16). The study was performed in accordance with Alzheimer’s Association guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. In the animal study, the experimental and housing conditions were approved by the Resort Committee of Animal Welfare (51-2022-P) and complied with the European Community Council Directive (2010/63/EC).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Laczó, M., Maleninska, K., Khazaalova, N. et al. Spatial pattern separation deficits in early Alzheimer’s disease are comparable in humans and animal models. Sci Rep (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36266-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-026-36266-y