Abstract

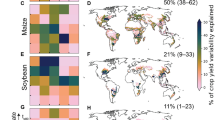

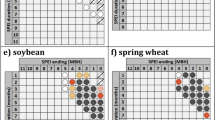

Compound hazards, like simultaneous occurrence of unusually dry and hot (DH) weather, cause cascading socio-economic damages that surpass univariate hazards. In the context of agricultural production, DH events triggered by pressure and moisture flux anomalies are responsible for some of the most severe agricultural losses across the globe. Most analyses focus on characterizing compound events in individual regions, and the extent of spatial synchrony of DH events and their impacts on crop production has yet to be quantified. Here, using observation-based gridded precipitation and temperature data, we find that the frequency of widespread spatial synchrony–defined as five or more regions simultaneously experiencing DH events–has increased nearly ten-fold over the past four decades, while confined events are declining. This rapid synchronization, especially in recent decades, reflects a non-linear response to global warming. At global scale, substantially larger productivity losses are observed during widespread DH events as compared to the spatially confined DH events. Wheat cropland exhibits the strongest losses during synchronized DH events, followed by maize, with weaker effects for rice. The results highlight the importance of considering the growing occurrence of spatially widespread DH events in assessments of agricultural risk, alongside analyses of individual regional extremes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

This study uses National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Climate Prediction Centre’s (CPC) Global Unified Gauge-Based Analysis of Daily Precipitation and Temperature dataset, which are freely available at https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cpc.globalprecip.html and https://psl.noaa.gov/data/gridded/data.cpc.globaltemp.html. The monthly crop-physical area data for the three selected staple crops (Rice, Maize, and Wheat) was obtained from the “GAEZ + _2015 Monthly Cropland Data”, which is retrieved https://mygeohub.org/publications/60/1. Daily estimates of global gross primary productivity (GPP) were obtained from the FluxSat v2.0 dataset, available at https://daac.ornl.gov/VEGETATION/guides/FluxSat_GPP_FPAR.html. The crop yield and population estimates are retrieved from https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

Code availability

The codes used in this study are developed in Python 3.11, and are made available via GitHub: http://github.com/waqar7006/Synchronized_compound_dry_hot_events.

References

García-Herrera, R., Díaz, J., Trigo, R. M., Luterbacher, J. & Fischer, E. M. A review of the European summer heat wave of 2003. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 40, 267–306 (2010).

Wegren, S. K. Food security and Russia’s 2010 drought. Eurasia. Geogr. Econ. 52, 140–156 (2011).

Christian, J. I., Basara, J. B., Hunt, E. D., Otkin, J. A. & Xiao, X. Flash drought development and cascading impacts associated with the 2010 Russian heatwave. Environ. Res. Lett. 15, 094078 (2020).

Beillouin, D., Schauberger, B., Bastos, A., Ciais, P. & Makowski, D. Impact of extreme weather conditions on European crop production in 2018. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 375, 20190510 (2020).

Mishra, A., Ray, L. K. & Reddy, V. M. Effects of compound hydro-meteorological extremes on rice yield in different cultivation practices in India. Theor. Appl Climatol. 155, 4507–4520 (2024).

Zscheischler, J. et al. A typology of compound weather and climate events. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 1, 333–347 (2020).

Lesk, C. et al. Compound heat and moisture extreme impacts on global crop yields under climate change. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 872–889 (2022).

Fahad, S. et al. Crop production under drought and heat stress: plant responses and management options. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1147 (2017).

Rezaei, E. E. et al. Climate change impacts on crop yields. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 4, 831–846 (2023).

Purushothaman, R. et al. Association of mid-reproductive stage canopy temperature depression with the molecular markers and grain yields of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) germplasm under terminal drought. Field Crops Res. 174, 1–11 (2015).

Bador, M. et al. Future summer mega-heatwave and record-breaking temperatures in a warmer France climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 12, 074025 (2017).

Abdelhakim, L. O. A., Zhou, R. & Ottosen, C.-O. Physiological responses of plants to combined drought and heat under elevated CO2. Agronomy 12, 2526 (2022).

Jarrett, U., Miller, S. & Mohtadi, H. Dry spells and global crop production: a multi-stressor and multi-timescale analysis. Ecol. Econ. 203, 107627 (2023).

Hunt, E. et al. Agricultural and food security impacts from the 2010 Russia flash drought. Weather Clim. Extremes 34, 100383 (2021).

Mishra, V., Thirumalai, K., Singh, D. & Aadhar, S. Future exacerbation of hot and dry summer monsoon extremes in India. Npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 3, 10 (2020).

Ridder, N. N. et al. Global hotspots for the occurrence of compound events. Nat. Commun. 11, 5956 (2020).

Koster, R. D. et al. Regions of strong coupling between soil moisture and precipitation. Science 305, 1138–1140 (2004).

Saharwardi, M. S. et al. Rising occurrence of compound droughts and heatwaves in the Arabian Peninsula linked to large-scale atmospheric circulations. Sci. Total Environ. 978, 179433 (2025).

Zscheischler, J. & Seneviratne, S. I. Dependence of drivers affects risks associated with compound events. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700263 (2017).

Alizadeh, M. R. et al. A century of observations reveals increasing likelihood of continental-scale compound dry-hot extremes. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz4571 (2020).

Herrera-Estrada, J. E. et al. Reduced moisture transport linked to drought propagation across North America. Geophys. Res. Lett. 46, 5243–5253 (2019).

Zhuang, Y. et al. Anthropogenic warming has ushered in an era of temperature-dominated droughts in the western United States. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn9389 (2024).

He, Y., Hu, X., Xu, W., Fang, J. & Shi, P. Increased probability and severity of compound dry and hot growing seasons over world’s major croplands. Sci. Total Environ. 824, 153885 (2022).

Mazdiyasni, O. & AghaKouchak, A. Substantial increase in concurrent droughts and heatwaves in the United States. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 11484–11489 (2015).

Mukherjee, S. & Mishra, A. K. Increase in compound drought and heatwaves in a warming world. Geophys. Res. Lett. 48, e2020GL090617 (2021).

Hassan, W. ul, Nayak, M. A. & Azam, M. F. Intensifying spatially compound heatwaves: Global implications to crop production and human population. Sci. Total Environ. 932, 172914 (2024).

Hassan, W. U. & Nayak, M. A. Global teleconnections in droughts caused by oceanic and atmospheric circulation patterns. Environ. Res. Lett. 16, 014007 (2020).

Singh, J., Ashfaq, M., Skinner, C. B., Anderson, W. B. & Singh, D. Amplified risk of spatially compounding droughts during co-occurrences of modes of natural ocean variability. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 4, 7 (2021).

Boers, N. et al. Complex networks reveal global pattern of extreme-rainfall teleconnections. Nature 566, 373–377 (2019).

Kornhuber, K. et al. Amplified Rossby waves enhance risk of concurrent heatwaves in major breadbasket regions. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 48–53 (2020).

Rogers, C. D., Kornhuber, K., Perkins-Kirkpatrick, S. E., Loikith, P. C. & Singh, D. Sixfold increase in historical Northern Hemisphere concurrent large heatwaves driven by warming and changing atmospheric circulations. J. Clim. 35, 1063–1078 (2022).

Branstator, G. Circumglobal teleconnections, the jet stream waveguide, and the North Atlantic Oscillation. J. Clim. 15, 1893–1910 (2002).

Alexander, M. A. et al. The atmospheric bridge: The influence of ENSO teleconnections on air–sea interaction over the global oceans. J. Clim. 15, 2205–2231 (2002).

Bevacqua, E., Zappa, G., Lehner, F. & Zscheischler, J. Precipitation trends determine future occurrences of compound hot–dry events. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 350–355 (2022).

Zhou, S., Yu, B. & Zhang, Y. Global concurrent climate extremes exacerbated by anthropogenic climate change. Sci. Adv. 9, eabo1638 (2023).

Stendel, M., Francis, J., White, R., Williams, P. D. & Woollings, T. The jet stream and climate change. In Climate change 327–357 (Elsevier, 2021).

Corti, S., Molteni, F. & Palmer, T. N. Signature of recent climate change in frequencies of natural atmospheric circulation regimes. Nature 398, 799–802 (1999).

Kornhuber, K. et al. Risks of synchronized low yields are underestimated in climate and crop model projections. Nat. Commun. 14, 3528 (2023).

Gaupp, F., Hall, J., Hochrainer-Stigler, S. & Dadson, S. Changing risks of simultaneous global breadbasket failure. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 54–57 (2020).

Mehrabi, Z. & Ramankutty, N. Synchronized failure of global crop production. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 780–786 (2019).

Bellemare, M. F. Rising food prices, food price volatility, and social unrest. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 97, 1–21 (2015).

Zscheischler, J. et al. A few extreme events dominate global interannual variability in gross primary production. Environ. Res. Lett. 9, 035001 (2014).

Schumacher, D. L. et al. Amplification of mega-heatwaves through heat torrents fuelled by upwind drought. Nat. Geosci. 12, 712–717 (2019).

Miralles, D. G., Gentine, P., Seneviratne, S. I. & Teuling, A. J. Land–atmospheric feedbacks during droughts and heatwaves: state of the science and current challenges. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1436, 19–35 (2019).

Heino, M. et al. Increased probability of hot and dry weather extremes during the growing season threatens global crop yields. Sci. Rep. 13, 3583 (2023).

He, Y., Fang, J., Xu, W. & Shi, P. Substantial increase of compound droughts and heatwaves in wheat growing seasons worldwide. Int. J. Climatol. 42, 5038–5054 (2022).

Zhu, P., Abramoff, R., Makowski, D. & Ciais, P. Uncovering the past and future climate drivers of wheat yield shocks in Europe with machine learning. Earths. Future 9, e2020EF001815 (2021).

Siebert, S. et al. The digital global map of irrigation areas–development and validation of map version 4. In Conference on International Agricultural Research for Development (Tropentag) (2006) https://www.tropentag.de/2006/abstracts/full/211.pdf.

Grogan, D., Frolking, S., Wisser, D., Prusevich, A. & Glidden, S. Global gridded crop harvested area, production, yield, and monthly physical area data circa 2015. Sci. Data 9, 15 (2022).

Liliane, T. N. & Charles, M. S. Factors affecting yield of crops. In Agronomy-Climate Change & Food Security 9 (IntechOpen, 2020) https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.90672.

Yao, Y., Liu, Y., Zhou, S., Song, J. & Fu, B. Soil moisture determines the recovery time of ecosystems from drought. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 3562–3574 (2023).

Jiao, T., Williams, C. A., De Kauwe, M. G., Schwalm, C. R. & Medlyn, B. E. Patterns of post-drought recovery are strongly influenced by drought duration, frequency, post-drought wetness, and bioclimatic setting. Glob. Change Biol. 27, 4630–4643 (2021).

Sheffield, J., Wood, E. F. & Roderick, M. L. Little change in global drought over the past 60 years. Nature 491, 435–438 (2012).

Zhang, P. et al. Abrupt shift to hotter and drier climate over inner East Asia beyond the tipping point. Science 370, 1095–1099 (2020).

Huang, J. et al. Recently amplified arctic warming has contributed to a continual global warming trend. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 875–879 (2017).

Dang, C. et al. Climate warming-induced phenology changes dominate vegetation productivity in Northern Hemisphere ecosystems. Ecol. Indic. 151, 110326 (2023).

Zhang, Y., Xu, M., Chen, H. & Adams, J. Global pattern of NPP to GPP ratio derived from MODIS data: effects of ecosystem type, geographical location and climate. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 18, 280–290 (2009).

CPC, C. Global Temperature and Unified Precipitation data provided by the NOAA PSL (PSL, 2020).

Reichle, R. H. et al. Assessment of MERRA-2 land surface hydrology estimates. J. Clim. 30, 2937–2960 (2017).

Hersbach, H. et al. The ERA5 global reanalysis. Quart. J. R. Meteor. Soc. 146, 1999–2049 (2020).

Beck, H. E. et al. Global-scale evaluation of 22 precipitation datasets using gauge observations and hydrological modeling. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 21, 6201–6217 (2017).

Frolking, S. et al. GAEZ+ _2015 global gridded crop harvest area, crop production, and crop yield-Metadata. Harvard Dataverse https://data.apps.fao.org/map/catalog/srv/api/records/7f8f21a1-452d-4ab5-a83a-f2cbccd15027/attachments/GAEZ%202015%20metadata.pdf (2020).

Grogan, D., Prusevich, A., Frolking, S., Wisser, D. & Glidden, S. GAEZ _2015 Monthly Cropland Data: Global gridded monthly crop physical area for 26 irrigated and rainfed crops. MyGeoHUB. https://doi.org/10.13019/J2BH-VB41 (2021).

Joiner, J. & Yoshida, Y. Satellite-based reflectances capture large fraction of variability in global gross primary production (GPP) at weekly time scales. Agric. For. Meteorol. 291, 108092 (2020).

FAOSTAT. Food and Agriculture Organization Corporate Statistical Database. https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (2025).

McKee, T. B., Doesken, N. J. & Kleist, J. The relationship of drought frequency and duration to time scales. In Proceedings of the 8th Conference on Applied Climatology, 17, 179–183 (Boston, 1993).

Vicente-Serrano, S. M., Beguería, S. & López-Moreno, J. I. A multiscalar drought index sensitive to global warming: the standardized precipitation evapotranspiration index. J. Clim. 23, 1696–1718 (2010).

Hassan, W. ul, Nayak, M. A. & Lyngwa, R. V. Recent changes in heatwaves and maximum temperatures over a complex terrain in the Himalayas. Sci. Total Environ. 794, 148706 (2021).

Hassan, W. et al. Unveiling the devastating effect of the spring 2022 mega-heatwave on the South Asian snowpack. Commun. Earth Environ. 5, 707 (2024).

Forster, P., Storelvmo, T. & Alterskjæ, K. IPCC sixth assessment report (AR6) working group 1: the physical science basis, chap. 7. (2021).

Iturbide, M. et al. An update of IPCC climate reference regions for subcontinental analysis of climate model data: definition and aggregated datasets. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 12, 2959–2970 (2020).

Enfield, D. B., Mestas-Nuñez, A. M. & Trimble, P. J. The Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation and its relation to rainfall and river flows in the continental U.S. Geophys. Res. Lett. 28, 2077–2080 (2001).

Lee, S. et al. Rapidly changing east asian marine heatwaves under a warming climate. JGR Oceans 128, e2023JC019761 (2023).

Chan, D. & Wu, Q. Attributing observed SST trends and subcontinental land warming to anthropogenic forcing during 1979–2005. J. Clim. 28, 3152–3170 (2015).

Benjamini, Y. & Yekutieli, D. The control of the false discovery rate in multiple testing under dependency. Ann. Stat. 29, 1165–1188 (2001).

Zscheischler, J. et al. Impact of large-scale climate extremes on biospheric carbon fluxes: An intercomparison based on MsTMIP data. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 28, 585–600 (2014).

Balashov, N. V. et al. Flood Impacts on Net Ecosystem Exchange in the Midwestern and Southern United States in 2019. JGR Atmos. 128, e2022JD037697 (2023).

Piao, S. et al. The impacts of climate extremes on the terrestrial carbon cycle: a review. Sci. China Earth Sci. 62, 1551–1563 (2019).

Marquardt, D. W. Comment: you should standardize the predictor variables in your regression models. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 75, 87–91 (1980).

Jiang, L. et al. Identification and characterization of global compound heat wave: comparison from four datasets of ERA5, Berkeley Earth, CHIRTS and CPC. Clim. Dyn. 62, 631–648 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Climate Change Center, an initiative of the National Center for Meteorology (NCM), Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (Ref No: RGC/03/4829-01-01). We extend our sincere gratitude to our colleagues at the National Institute of Technology Srinagar and Climate Change Center, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology for their support, insightful discussions, and constructive feedback throughout this study. We would like to thank the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s MODIS project, for archiving and enabling public access to their data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

W.U.H. conceived and designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. M.A.N., M.S.S, H.G., H.P.D., C.A., D.Y. helped in design and co-wrote the manuscript. I.H., and Y.A. supervised and helped in editing and writing final draft. All authors participated in the interpretation of results.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Earth and Environment thanks Lina Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Primary Handling Editors: Fiona Tang, Aliénor Lavergne, and Mengjie Wang. [A peer review file is available].

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan, W.u., Nayak, M.A., Saharwardi, M.S. et al. The growing threat of spatially synchronized dry-hot events to global ecosystem productivity. Commun Earth Environ (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-026-03203-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-026-03203-w