Abstract

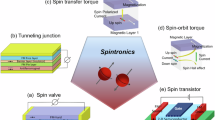

The demand for data processing in high-performance computing is growing rapidly. Extrapolating these trends to the long term suggests that a switch, which is more energy-efficient than a silicon complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) switch, is necessary to support future computing needs. Spintronic logic, which encodes information using spin and magnetism, can theoretically provide an energy-efficient switch; however, it is less mature than CMOS logic and has yet to be realized at the level of a full processor system, thus warranting an informed review of spintronic logic technologies with guidelines for future research directions. In this Review, we contextualize spintronic logic within the broader goals of beyond-CMOS computing. We then provide an overview of five types of spintronic logic, discussing the operating principles, advantages, advancements and challenges of each type. We highlight that future research in spintronic logic should focus on the realization of low-voltage operation, transparent benchmarking for application-level tasks, development of computing architectures that exploit unique features of spintronics such as non-volatility and high endurance, and adaptation of spintronic logic to circuits usable for both computing and memory. This Review provides motivation and direction for high-risk, high-reward research in spintronic logic that should be pursued in parallel with the CMOS road map.

Key points

-

Logic devices beyond the complementary metal-oxide semiconductor (CMOS) transistor must address multiple sources of energy loss to achieve system-level energy efficiency.

-

Spintronic devices for computing can be categorized into applications for high-performance computing, unconventional computing and CMOS+X.

-

Spintronic logic can theoretically address the needs of beyond-CMOS high-performance computing, but a demonstration of that goal has yet to be realized.

-

For five established spintronic logic types, the advantages, recent advancements in simulation, recent advancements in experiments and current challenges are discussed.

-

Benchmarking of spintronic logic should include transparent methods that both capture device imperfections and can be updated as the technology matures, and they should use application-level tasks that capture the unique benefits of the device.

-

Research priorities for spintronic logic are identified, including the need for voltage-driven switching, gain in more device concepts, higher output read-out signals, higher ratio of spintronic gates over silicon gates in spintronic circuits and new materials for faster dynamics.

-

High-risk, high-reward research in spintronic logic should be pursued in parallel with the CMOS road map.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

$119.00 per year

only $9.92 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on SpringerLink

- Instant access to the full article PDF.

USD 39.95

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Andrae, A. S. G. & Edler, T. On global electricity usage of communication technology: trends to 2030. Challenges 6, 117–157 (2015).

Jones, N. How to stop data centres from gobbling up the world’s electricity. Nature 561, 163–166 (2018).

IRDS. International Roadmap for Devices and Systems IRDS. IEEE https://irds.ieee.org (2023).

Manipatruni, S., Nikonov, D. E. & Young, I. A. Beyond CMOS computing with spin and polarization. Nat. Phys. 14, 338–343 (2018).

Sharma, V. & Rajawat, A. Review of approaches for radiation hardened combinational logic in CMOS silicon technology. IETE Tech. Rev. 35, 562–573 (2018).

Fanghui, R., Jander, A., Dhagat, P. & Nordman, C. Radiation tolerance of magnetic tunnel junctions with MgO tunnel barriers. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 59, 3034–3038 (2012).

Hughes, H. et al. Radiation studies of spin-transfer torque materials and devices. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 59, 3027–3033 (2012).

Alamdar, M. et al. Irradiation effects on perpendicular anisotropy spin–orbit torque magnetic tunnel junctions. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 68, 665–670 (2021).

Bennett, C. H. et al. Radiation response of domain-wall magnetic tunnel junction logic devices. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 71, 454–460 (2024).

Mochizuki, A., Kimura, H., Ibuki, M. & Hanyu, T. TMR-based logic-in-memory circuit for low-power VLSI. IEICE Trans. Fundamentals Electron. Commun. Computer Sci. 88, 1408–1415 (2005).

Gebregiorgis, A., Bishnoi, R. & Tahoori, M. B. Spintronic normally-off heterogenous system-on-chip design. In 2018 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conf. & Exhibition (DATE) 113–118 (IEEE, 2018). This paper shows how a normally-off system on chip can be designed by a hybrid architecture containing conventional CMOS bistable elements as well as different flavours of spintronic-based non-volatile storage elements.

Deng, E., Anghel, L., Prenat, G. & Zhao, W. Multi-context non-volatile content addressable memory using magnetic tunnel junctions. In 2016 IEEE/ACM Int. Symp. Nanoscale Architectures 103–108 (IEEE, 2016). This article shows that content-addressable memories can be made using MTJs.

Jin, H. et al. Domain wall-magnetic tunnel junction analog content addressable memory using current and projected data. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 23, 20–28 (2024).

Iwai, H. Future of nano CMOS technology. In 28th Symp. Microelectronics Technology and Devices (IEEE, 2013).

Radosavljevic, M. & Kavalieros, J. 3D-stacked CMOS takes Moore’s law to new heights. IEEE Spectrum 32–37 (IEEE, 2022).

Chang, C. H. et al. Critical process features enabling aggressive contacted gate pitch scaling for 3 nm CMOS technology and beyond. In Technical Digest—Int. Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 623–626 (IEEE, 2022).

Chung, Y.-Y. et al. First demonstration of GAA monolayer-MoS2 nanosheet nFET with 410 μA μm ID 1V VD at 40 nm gate length. In Technical Digest—Int. Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 823–826 (IEEE, 2022).

Rupp, K. microprocessor-trend-data. GitHub https://github.com/karlrupp/microprocessor-trend-data (2022).

Zhang, K. et al. SRAM design on 65-nm CMOS technology with dynamic sleep transistor for leakage reduction. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 40, 895–900 (2005).

Tachibana, F. et al. A 27% active and 85% standby power reduction in dual-power-supply SRAM using BL power calculator and digitally controllable retention circuit. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 49, 118–126 (2014).

Sabry Aly, M. M. et al. Energy-efficient abundant-data computing: the N3XT 1,000×. Computer 48, 24–33 (2015).

Singer, P. Scaling the BEOL: a toolbox filled with new processes, boosters and conductors. Semiconductor Digest. https://www.semiconductor-digest.com/scaling-the-beol-a-toolbox-filled-with-new-processes-boosters-and-conductors/ (2020). This article shows that interconnect energy dissipation is a dominant source of energy loss in modern CPUs and memories.

Prasad, D. & Naeemi, A. Interconnect design and technology optimization for conventional and emerging nanoscale devices: a physical design perspective. In Technical Digest—Int. Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 5.1.1–5.1.4 (IEEE, 2018).

Dang, F., Sun, X. K., Bin Liu, K., Xu, Y. F. & Liu, Y. H. A survey on clock synchronization in the industrial internet. J. Comput. Sci. Technol. 38, 146–165 (2023).

Likamwa, R., Hou, Y., Gao, Y., Polansky, M. & Zhong, L. RedEye: analog ConvNet image sensor architecture for continuous mobile vision. In 43rd Int. Symp. Computer Architecture (ISCA) 255–266 (IEEE, 2016).

Wilson, R. B. et al. Ultrafast magnetic switching of GdFeCo with electronic heat currents. Phys. Rev. B 95, 180409 (2017).

Guan, Y. et al. Ionitronic manipulation of current-induced domain wall motion in synthetic antiferromagnets. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–8 (2021).

Alam, S. M. et al. Versatile STT-MRAM architecture for memory and emerging applications. In IEEE 34th Magnetic Recording Conf. (TMRC) (IEEE, 2023).

Muller, J. et al. From emergence to prevalence: 22FDX® embedded STT-MRAM. In IEEE International Memory Workshop (IMW) (2022).

Naik, V. B. et al. STT-MRAM product reliability and cross-talk. In IEEE Electron Devices Technology and Manufacturing Conf. (EDTM) 366–368 (IEEE, 2022).

Jew, T. MRAM in microcontroller and microprocessor product applications. In Technical Digest—Int. Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 11.1.1–11.1.3 (IEEE, 2020).

Ross, A. et al. Multilayer spintronic neural networks with radiofrequency connections. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 1273–1280 (2023).

Sakhare, S. et al. Enablement of STT-MRAM as last level cache for the high performance computing domain at the 5nm node. In Technical Digest—Int. Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 18.3.1–18.3.4 (IEEE, 2018).

Kan, J. J. et al. A study on practically unlimited endurance of STT-MRAM. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 64, 3639–3646 (2017).

Ikeda, S. et al. A perpendicular-anisotropy CoFeB–MgO magnetic tunnel junction. Nat. Mater. 9, 721–724 (2010).

Streetman, B. & Banerjee, S. Solid State Electronic Devices, Global Edition (Pearson Education, 2015).

Rao, S. et al. A systematic assessment of W-doped CoFeB single free layers for low power STT-MRAM applications. Electronics 10, 2384 (2021).

Manipatruni, S. et al. Scalable energy-efficient magnetoelectric spin–orbit logic. Nature 565, 35–42 (2019). This article introduces the proposal of MESO logic.

Nikonov, D. E. & Young, I. A. Benchmarking of beyond-CMOS exploratory devices for logic integrated circuits. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits 1, 3–11 (2015).

Fedorova, N. S., Nikonov, D. E., Li, H., Young, I. A. & Íñiguez, J. First-principles Landau-like potential for BiFeO3 and related materials. Phys. Rev. B 106, 165122 (2022).

Fedorova, N. S. et al. Understanding magnetoelectric switching in BiFeO3 thin films. Phys. Rev. B 109, 085116 (2023).

Liu, H. et al. Synchronous circuit design with beyond-CMOS magnetoelectric spin-orbit devices toward 100-mV logic. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits 5, 1–9 (2019).

Li, H., Lin, C. C., Nikonov, D. E. & Young, I. A. Differential electrically insulated magnetoelectric spin–orbit logic circuits. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits 7, 18–25 (2021).

Li, H. et al. Physics-based models for magneto-electric spin–orbit logic circuits. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits 8, 10–18 (2022).

Liao, Y. C. et al. Evaluating the performances of the ultralow power magnetoelectric random access memory with a physics-based compact model of the antiferromagnet/ferromagnet bilayer. IEEE Trans. Electron. Devices 69, 2331–2337 (2022).

Rothe, R. et al. Energy efficient logic and memory design with beyond-CMOS magnetoelectric spin–orbit (MESO) technology toward ultralow supply voltage. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits 9, 124–133 (2023).

Pham, V. T. et al. Spin–orbit magnetic state readout in scaled ferromagnetic/heavy metal nanostructures. Nat. Electron. 3, 309–315 (2020). This article presents experimental observation of spin–orbit detection of magnetic states.

Groen, I. et al. Disentangling spin, anomalous, and planar Hall effects in ferromagnet-heavy-metal nanostructures. Phys. Rev. Appl. 15, 044010 (2021).

Prasad, B. et al. Ultralow voltage manipulation of ferromagnetism. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001943 (2020).

Debashis, P. et al. Low-voltage and high-speed switching of a magnetoelectric element for energy efficient compute. In Technical Digest—Int. Electron Devices Meeting (IEDM) 3641–3644 (IEEE, 2022).

Parsonnet, E. et al. Toward intrinsic ferroelectric switching in multiferroic BiFeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 067601 (2020).

Vaz, D. C. et al. Voltage-based magnetization switching and reading in magnetoelectric spin–orbit nanodevices. Nat. Commun. 15, 1902 (2024). This article demonstrates the latest experimental advances for MESO logic.

Choi, W. Y. et al. All-electrical spin-to-charge conversion in sputtered BixSe1–x. Nano Lett. 22, 7992–7999 (2022).

Herling, F. et al. Gate tunability of highly efficient spin-to-charge conversion by spin Hall effect in graphene proximitized with WSe2. APL Mater. 8, 071103 (2020).

Currivan, J. A., Jang, Y., Mascaro, M. D., Baldo, M. A. & Ross, C. A. Low energy magnetic domain wall logic in short, narrow, ferromagnetic wires. IEEE Magn. Lett. 3, 3000104 (2012).

Zogbi, N. et al. Parallel matrix multiplication using voltage-controlled magnetic anisotropy domain wall logic. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits. 9, https://doi.org/10.1109/jxcdc.2023.3266441 (2023). This work shows the high-performance compute capability and prospects for DW-MTJ logic, as well as a path towards lower-energy voltage control.

Alamdar, M. et al. Domain wall–magnetic tunnel junction spin–orbit torque devices and circuits for in-memory computing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 112401 (2021). This article presents an experimental demonstration of DW-MTJ devices and small circuits, operating with spin–orbit torque and electrically nucleated domain walls.

Xiao, T. P. et al. Energy and performance benchmarking of a domain wall–magnetic tunnel junction multibit adder. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits 5, 188–196 (2019).

Morris, D., Bromberg, D., Zhu, J. & Pileggi, L. mLogic: ultra-low voltage non-volatile logic circuits using STT-MTJ devices. In DAC Design Automation Conf. 486–491 (IEEE, 2012).

Jouppi, N. P. et al. In-datacenter performance analysis of a tensor processing unit. In Proc. 44th Annual Int. Symp. Computer Architecture 1–12 (2017).

Currivan-Incorvia, J. A. et al. Logic circuit prototypes for three-terminal magnetic tunnel junctions with mobile domain walls. Nat. Commun. 7, 10275 (2016).

Liu, S. et al. A domain wall–magnetic tunnel junction artificial synapse with notched geometry for accurate and efficient training of deep neural networks. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 202405 (2021).

Liu, S. et al. Bayesian neural networks using magnetic tunnel junction-based probabilistic in-memory computing. Front. Nanotechnol. 4, 1092820 (2022).

Leonard, T. et al. Shape-dependent multi-weight magnetic artificial synapses for neuromorphic computing. Adv. Electron. Mater. 8, 2200563 (2022). This work presents experimental DW-MTJs showing high control of the DW position.

Leonard, T., Liu, S., Jin, H. & Incorvia, J. A. C. Stochastic domain wall–magnetic tunnel junction artificial neurons for noise-resilient spiking neural networks. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 26 (2023).

Cui, C., Liu, S., Kwon, J. & Incorvia, J. A. C. Domain wall magnetic tunnel junction reliable integrate and fire neuron. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.14851 (2024).

Nikonov, D. E., Bourianoff, G. I. & Ghani, T. Proposal of a spin torque majority gate logic. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 32, 1128–1130 (2011).

Raymenants, E. et al. Nanoscale domain wall devices with magnetic tunnel junction read and write. Nat. Electron. 4, 392–398 (2021). This article presents important experiments on electrical control of domain walls for STMGs and DW-MTJs.

Vaysset, A. et al. Toward error-free scaled spin torque majority gates. AIP Adv. 6, 065304 (2016).

Yang, S. H., Ryu, K. S. & Parkin, S. Domain-wall velocities of up to 750 m s–1 driven by exchange-coupling torque in synthetic antiferromagnets. Nat. Nanotechnol. 10, 221–226 (2015).

Bhattacharya, D. et al. 3D interconnected magnetic nanowire networks as potential integrated multistate memristors. Nano Lett. 22, 10010–10017 (2022).

Becherer, M. et al. A monolithic 3D integrated nanomagnetic co-processing unit. Solid. State Electron. 115, 74–80 (2016). This work gives a clear path towards 3D integration of field-coupled NML, summarizing the basic building blocks for a digital co-processing unit.

Becherer, M. 3D nanomagnetic logic. In Emerging Non-Volatile Memory Technologies (eds Lew, W. S. et al.) 3–438 (Springer Nature Limited, 2021).

Hassan, N. et al. Secure logic locking with strain-protected nanomagnet logic. In ACM/IEEE Design Automation Conf. (DAC) 127–132 (IEEE, 2021).

Edwards, A. J. et al. Physically and algorithmically secure logic locking with hybrid CMOS/nanomagnet logic circuits. In Proc. 2022 Conf. Exhibition on Design, Automation & Test in Europe 17–22 (IEEE, 2022).

Breitkreutz, S. et al. Compact modeling of perpendicular nanomagnetic logic based on threshold gates. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 17–104 (2014).

Turvani, G., Riente, F., Plozner, E., Schmitt-Landsiedel, D. & Gamm, S. B. V. A compact physical model for the simulation of pNML-based architectures. AIP Adv. 7, 56005 (2017).

Žiemys, G. et al. Modeling and simulation of nanomagnetic logic with cadence virtuoso using Verilog-A. Solid. State Electron. 125, 247–253 (2016).

Garlando, U. et al. Architectural exploration of perpendicular nano magnetic logic based circuits. Integration 63, 275–282 (2018).

Riente, F. et al. MagCAD: tool for the design of 3-D magnetic circuits. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits 3, 65–73 (2017).

Riente, F. et al. ToPoliNano: a CAD tool for nano magnetic logic. IEEE Trans. Comput. Des. Integr. Circuits Syst. 36, 1061–1074 (2017).

Bhoi, B. K., Misra, N. K. & Pradhan, M. Synthesis and simulation study of non-restoring cell architecture layout in perpendicular nano-magnetic logic. J. Comput. Electron. 19, 407–418 (2020).

Kiermaier, J. et al. Information transport in field-coupled nanomagnetic logic devices. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 17B902 (2013).

Eichwald, I. et al. Nanomagnetic logic: error-free, directed signal transmission by an inverter chain. IEEE Trans. Magn. 48, 4332–4335 (2012).

Breitkreutz, S. et al. Nanomagnetic logic: demonstration of directed signal flow for field-coupled computing devices. In European Solid-State Device Research Conf. 323–326 (IEEE, 2011).

Breitkreutz, S. et al. Controlled reversal of Co/Pt dots for nanomagnetic logic applications. J. Appl. Phys. 111, 07A715 (2012).

Breitkreutz, S. et al. Majority gate for nanomagnetic logic with perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. IEEE Trans. Magn. 48, 4336–4339 (2012).

Papp, A. et al. Threshold gate-based circuits from nanomagnetic logic. IEEE Trans. Nanotechnol. 13, 990–996 (2014).

Breitkreutz, S. et al. 1-Bit full adder in perpendicular nanomagnetic logic using a novel 5-input majority gate. EPJ Web Conf. 75, 05001 (2014).

Eichwald, I. et al. Signal crossing in perpendicular nanomagnetic logic. J. Appl. Phys. 115, 17–510 (2014).

Eichwald, I. et al. Majority logic gate for 3D magnetic computing. Nanotechnology 25, 335202 (2014).

Ziemys, G. et al. Characterization of the magnetization reversal of perpendicular nanomagnetic logic clocked in the ns-range. AIP Adv. 6, 56404 (2016).

Mendsich, S., Ahrens, V., Kiechle, M., Papp, A. & Becherer, M. Perpendicular nanomagnetic logic based on low anisotropy Co\Ni multilayer. J. Magn. Magn Mater. 510, 166626 (2020).

Mendisch, S. et al. Controlling domain-wall nucleation in Ta/Co–Fe–B/MgO nanomagnets via local Ga+ ion irradiation. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16, 014039 (2021).

Favaro, D. et al. Enabling logic computation between Ta/CoFeB/MgO nanomagnets. IEEE Trans. Magn. 59, 1–10 (2023).

Khitun, A., Kang, Wang, L. & Wang, K. L. Non-volatile magnonic logic circuits engineering. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 34306 (2011).

Mahmoud, A. et al. Introduction to spin wave computing. J. Appl. Phys. 128, 161101 (2020).

Chumak, A. V., Vasyuchka, V. I., Serga, A. A. & Hillebrands, B. Magnon spintronics. Nat. Phys. 11, 453–461 (2015).

Kostylev, M. P., Serga, A. A., Schneider, T., Leven, B. & Hillebrands, B. Spin-wave logical gates. Appl. Phys. Lett. 87, 1–3 (2005).

Lee, K. S. & Kim, S. K. Conceptual design of spin wave logic gates based on a Mach–Zehnder-type spin wave interferometer for universal logic functions. J. Appl. Phys. 104, 53909 (2008).

Kostylev, M. P., Serga, A. A., Schneider, T., Leven, B. & Hillebrands, B. Theory of dipole-exchange spin wave spectrum for ferromagnetic films with mixed exchange boundary conditions. J. Phys. C: Solid. State Phys. 19, 7013 (1986).

Ciubotaru, F., Devolder, T., Manfrini, M., Adelmann, C. & Radu, I. P. All electrical propagating spin wave spectroscopy with broadband wavevector capability. Appl. Phys. Lett. 109, 12403 (2016).

Klingler, S. et al. Design of a spin-wave majority gate employing mode selection. Appl. Phys. Lett. 105, 152410 (2014).

Mahmoud, A. et al. Spin wave based full adder. In Proc. IEEE Int. Symp. Circuits and Systems 1–5 (IEEE, 2021).

Mahmoud, A. N. et al. A spin wave-based approximate 4:2 compressor: seeking the most energy-efficient digital computing paradigm. IEEE Nanotechnol. Mag. 16, 47–56 (2022).

Zografos, O. et al. Design and benchmarking of hybrid CMOS-Spin Wave Device Circuits compared to 10nm CMOS. In Int. Conf. Nanotechnology 686–689 (IEEE, 2015).

Mahmoud, A. et al. Would Magnonic Circuits Outperform CMOS Counterparts? In Proc. ACM Great Lakes Symp. VLSI (GLSVLSI) 309–313 (ACM, 2022).

Fischer, T. et al. Experimental prototype of a spin-wave majority gate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 152401 (2017).

Kanazawa, N. et al. The role of Snell’s law for a magnonic majority gate. Sci. Rep. 7, 1–8 (2017).

Talmelli, G. et al. Reconfigurable submicrometer spin-wave majority gate with electrical transducers. Sci. Adv. 6, 4042–4060 (2020). This article presents an experimental demonstration of spin wave logic.

Mahmoud, A. N. et al. Spin wave normalization toward all magnonic circuits. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I 68, 536–549 (2021).

Wang, Q. et al. A magnonic directional coupler for integrated magnonic half-adders. Nat. Electron. 3, 765–774 (2020).

Vanderveken, F. et al. Lumped circuit model for inductive antenna spin-wave transducers. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–13 (2022).

Mitrofanova, A., Safin, A., Kravchenko, O., Nikitov, S. & Kirilyuk, A. Optically initialized and current-controlled logical element based on antiferromagnetic-heavy metal heterostructures for neuromorphic computing. Appl. Phys. Lett. 120, 072402 (2022).

Yang, Q. et al. Realization of high spin injection through chiral molecules and its application in logic device. IEEE Electron. Device Lett. 43, 1862–1865 (2022).

Arava, H. et al. Computational logic with square rings of nanomagnets. Nanotechnology 29, 265205 (2018).

Rakheja, S., Flatté, M. E. & Kent, A. D. Voltage-controlled topological spin switch for ultralow-energy computing: performance modeling and benchmarking. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 054009 (2019).

Allwood, D. A. et al. Magnetic domain-wall logic. Science 309, 1688–1692 (2005).

Luo, Z. et al. Current-driven magnetic domain-wall logic. Nature 579, 214–218 (2020).

Perricone, R. et al. An energy efficient non-volatile flip-flop based on CoMET technology. In Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conf. Exhibition (DATE) 390–395 (IEEE, 2019).

Friedman, J. S. et al. Cascaded spintronic logic with low-dimensional carbon. Nat. Commun. 8, 15635 (2017).

Khokhriakov, D. et al. Multifunctional spin logic operations in graphene spin circuits. Phys. Rev. Appl. 18, 64063 (2022).

Pan, C. & Naeemi, A. An expanded benchmarking of beyond-CMOS devices based on Boolean and neuromorphic representative circuits. IEEE J. Explor. Solid-State Comput. Devices Circuits 3, 101–110 (2017). This work expands the benchmarking framework for spintronic logic by considering both Boolean and non-Boolean circuits and by adding new devices such as three magnetoelectric devices and new flavours of all-spin logic and charge-coupled spin logic.

Acknowledgements

J.A.C.I., T.P.X. and N.Z. acknowledge funding through the Rad Edge Grand Challenge project, which is part of the Laboratory Directed Research and Development Program at Sandia National Laboratories. M.B. acknowledges support by the German Research Foundation (DFG) project numbers 114933698, 229838035 and 403505866. S.C., C.A. and F. Catthoor acknowledge support by imec’s Industrial Affiliate Programs on Magnetic Memory and on Exploratory Logic. F. Casanova acknowledges funding by ‘FEINMAN 2.0’ Intel Science Technology Center, the Spanish Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities (MCIU) MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 (Grant No. CEX2020-001038-M) and MICIU/AEI and ERDF/EU (Grant No. PID2021-122511OB-I00). This article has been authored by an employee of National Technology & Engineering Solutions of Sandia, LLC under Contract No. DE-NA0003525 with the US Department of Energy (DOE); the employee owns all right, title and interest in and to the article and is solely responsible for its contents. The US Government retains and the publisher, by accepting the article for publication, acknowledges that the US Government retains a non-exclusive, paid-up, irrevocable, worldwide licence to publish or reproduce the published form of this article or allow others to do so, for US Government purposes. The DOE will provide public access to these results of federally sponsored research in accordance with the DOE Public Access Plan (https://www.energy.gov/downloads/doe-public-access-plan). This paper describes objective technical results and analysis. Any subjective views or opinions that might be expressed in the paper do not necessarily represent the views of the DOE or the US Government.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors researched data for the article and substantially contributed to discussion of content. J.A.C.I., S.C., T.P.X., N.Z., A.N., C.A., F. Catthoor and F. Casanova wrote the article. J.A.C.I., S.C., T.P.X. and N.Z. reviewed and edited the manuscript before submission.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Reviews Electrical Engineering thanks Dmitri E. Nikonov, Joseph S. Friedman and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Incorvia, J.A.C., Xiao, T.P., Zogbi, N. et al. Spintronics for achieving system-level energy-efficient logic. Nat Rev Electr Eng 1, 700–713 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s44287-024-00103-z

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s44287-024-00103-z

This article is cited by

-

Spintronic memristors for computing

npj Spintronics (2025)