Abstract

In the silkworm, Bombyx mori, the female is the heterogametic (ZW) sex and the male is homogametic (ZZ). The female heterogamety is a typical situation in the insect order Lepidoptera. Although the W chromosome in silkworm is strongly female determining, no W-linked gene for a morphological character has been found on it. The Z chromosome carries important traits of economic value as well as genes for various phenotypic traits, but only 2% of molecular information based on its relative size is known. Studies conducted so far indicate that the Z-linked genes are not dosage compensated. In the present study, we constructed a genetic map of randomly amplified polymorphic DNA fragments (RAPD), simple sequence repeats (SSR), and fluorescent intersimple sequence repeat PCR (FISSR) markers for the Z chromosome using a backcross mapping population. A total of 16 Z-linked markers were identified, characterized, and mapped using od, a recessive trait for translucent skin as an anchor marker yielding a total recombination map of 334.5 cM. The linkage distances obtained suggested that the markers were distributed throughout the Z chromosome. Four RAPD and four SSR markers that were linked to W chromosome were also identified. The proposed mapping approach should be useful to identify and map sex-linked traits in the silkworm. The economic and evolutionary significance of Z- and W-linked genes in silkworm, in particular, and lepidopterans, in general, is discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In many organisms, sex is determined by a set of dimorphic sex chromosomes (X and Y) that are thought to have evolved from an autosome (Ohno, 1967; Bull, 1983; Guttman and Charlesworth, 1998). Sex chromosomes have evolved independently many times, and Y chromosomes lack genetic recombination over most or all of their length (Jegalian and Page, 1998; Charlesworth and Charlesworth, 2000). In Drosophila melanogaster and humans, the Y chromosome has lost most of its active genes (Carvalho et al, 2001; Lahn et al, 2001), and those remaining appear largely to affect male-specific functions. For example, several genes have been identified on the Y chromosome of D. melanogaster that are expressed during spermatogenesis and influence fitness primarily through their effect on male reproductive success (Chippindale and Rice, 2001; Carvalho, 2002). Similarly, in humans, apart from the testis-determining factor, the Y chromosome contains only a few genes or gene families, many of which have testes-specific functions (Lahn et al, 2001). Recently, Skaletsky et al (2003) reported that more than 63 million base pairs (Mb) of the Y chromosome are male-specific, consisting of some 23 Mb of euchromatin and a variable amount of heterochromatin.

In the domesticated silkworm, Bombyx mori, the chromosomal sex determination is reversed: the male is the homogametic sex (ZZ) and the female is heterogametic (ZW). The ZW bivalent is reported to have no crossing over (Sturtevant, 1915; Tazima, 1978). These features have been confirmed in other lepidopteran insects (Traut, 1977), and may prove valuable for the detection of sex-linked characters, and for studying the evolution of sex chromosomes. Female sex in silkworm is determined by the presence of a single W chromosome, regardless of the number of autosomes or Z chromosomes (Hasimoto, 1930); hence, the W chromosome is assumed to carry a primary determinant for femaleness. Using irradiated chromosome fragments, Tazima (1964) confirmed this model of sex determination in B. mori and showed that the primary sex determinants are localized at one end of the W chromosome.

Although more than 200 visible mutations have been placed on silkworm linkage maps (Fujii et al, 1998), no gene for a morphological character has so far been mapped to the W chromosome. In search of W chromosome-specific markers, Abe et al (1995, 1996, 1998a, 2000) and Ohbayashi et al (1996) identified five RAPDs. Using these markers for subsequent cloning and sequencing of W-derived BAC clones, they revealed that the W chromosome is largely composed of nested, full-length retrotransposable elements (Abe et al, 1998b, 2000, 2001). Owing to their high repetition, these kinds of sequences are difficult to use for chromosome walking, or even for isolation of contigs of interest. Identification of additional W-linked markers would be useful for establishing a global map to facilitate the assembly of W contigs, and for finding sex-determining gene(s). Further, intensive analysis of the W chromosome of B. mori could shed light on its organization and evolution.

The classical linkage map of the Z chromosome of B. mori contains 15 morphological traits dispersed over 50 cM (centiMorgans) (Fujii et al, 1998). They include a number of important traits of economic value, such as late maturity (Lm), which affects voltinism (number of life cycles in a year), moltinism (number of larval moults per life cycle), and quantitative traits such as cocoon weight and cocoon shell weight (Tazima, 1978). In addition, the Z chromosome harbors genes for various phenotypic traits expressed in the egg, larva, and moth, such as Giant egg (Ge), Green eggshell color (Gre), elongated larval body (e), chocolate larval color (sch), translucent larval skin (od), and Vestigial wing (Vg). Recently, Yasukochi (1998) identified 18 Z-linked RAPD markers, and Koike et al (2003) identified 13 additional genes in a contiguous 320 kb walk of the Z-chromosome starting with the sex-linked marker, Bmkettin, a homolog of the D. kettin muscle protein gene (Suzuki et al, 1998, 1999).

Characteristics affecting reproductive isolation and host race formation appear to be predominantly sex linked in many groups of lepidoptera (Sperling, 1994). Thus, analysis of Z-linked genes especially those controlling maturity, diapause, body size, etc. in silkworm will help in evaluating the role of these traits in speciation and evolution. Analysis of the repeat content and the interspersed elements on the Z chromosome and their distribution across the chromosome may help to elucidate dosage compensation for genes that have not previously been investigated (Suzuki et al, 1998).

Molecular linkage maps using a variety of markers have been constructed for the silkworm (Nagaraju and Goldsmith, 2002; Goldsmith et al, 2005). In the present study, a mapping population was constructed specifically to identify and map sex chromosome-linked markers. Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA fragments (RAPD), simple sequence repeats (SSR), and fluorescent intersimple sequence repeat PCR (FISSR) markers were identified, characterized, and analyzed to construct a molecular linkage map of the Z chromosome.

Materials and methods

Silkworm strains

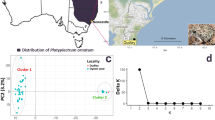

A silkworm strain that carries a Z-linked mutation, translucent larval skin (od), was used as a reference for Z chromosome mapping. Normal and translucent larvae can be unambiguously identified in a segregating population. F1 hybrids were raised by crossing a diapausing, translucent (Zod) female with a wild-type (ZPM) Pure Mysore male. A backcross population was raised by crossing an F1 hybrid male to a translucent (Zod) female in order to obtain a recombination map of the Z chromosome (Figure 1).

DNA extraction

All DNA extractions were performed on moths frozen in liquid nitrogen (after oviposition, in the case of females) using the method of Nagaraja and Nagaraju (1995).

RAPD analysis

RAPD analysis was carried out using 560 random primers (OPA to OPZ, OPAA and OPAH kits) obtained from Operon Technologies, Alameda, CA, USA. The amplification of genomic DNA was performed according to Nagaraja and Nagaraju (1995).

SSR analysis

SSR analysis was performed using primer sets for 216 different microsatellite loci derived from a variety of sources: a subgenomic library (Reddy et al, 1999), GenBank submissions (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov), expressed sequence tags (ESTs) from SilkBase (http://www.ab.a.u-tokyo.ac.jp/silkbase, Mita et al, 2003), Z-linked BAC clones (Koike et al, 2003), and whole genome shotgun (WGS) sequence data (http://www.ddbj.nig.ac.jp/whatsnew/040423-e.html, Mita et al, 2004). PCR amplification was performed in a 10 μl volume containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dNTPs, 0.1 U of AmpliTaq Gold (Perkin Elmer), 4 μM primer, and 10–20 ng of genomic DNA. The thermal cycling conditions were as follows: initial denaturation of 2 min at 94°C, 35 cycles of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 56°C, and 2 min at 72°C, and a final extension of 10 min at 72°C. The products were separated on a 3% metaphor agarose (FMC) gel.

FISSR-PCR analysis

A total of 43 FISSR-PCR primers labeled on the 5′ end with TAMRA fluorescent dye were screened and PCR amplification was performed as described in Nagaraju et al (2002).

Sequence analysis of Z- and W-specific markers

Z-chromosome linked RAPD, SSR, and FISSR markers and W-specific SSR markers were sequenced using an automated ABI 373 DNA sequencer and analyzed using tools available on the NCBI database. The sequences of RAPD, SSR, and FISSR were deposited in GenBank.

Identification of Z- and W-derived markers

In the backcross population (BC) derived from F1 (♂) (translucent (od) (♀) X Pure Mysore (♂)) × translucent (od) (♀), the od female Z-linked markers, as expected, appear only in F1 males and segregate in the ratio of 1:1 among BC females, whereas all BC males carry markers (Table 1). In these crosses, the Pure Mysore strain Z-linked markers will not appear in a sex-specific manner in the F1 offspring (Table 1), but will segregate in the BC and can only be identified as sex linked by using the reciprocal cross, which was not performed in the present study. Therefore, the BC raised in the present study facilitated identification only of od strain Z-linked markers. The markers that were present only in the females of the parents, F1, and BC were considered as W-linked markers. For autosomal markers, all the F1 offspring were identical, while backcross males and females showed segregation in the ratio of 1:1 for Pure Mysore-derived markers.

Genotyping

The Z-linked DNA markers derived from the translucent (od) strain will appear only in the F1 males (Table 1). The RAPD and FISSR-PCR Z-linked markers segregated as dominant markers and the SSR markers segregated as codominant markers. All markers were scored as present (coded as 1) or absent (coded as 0) in the backcross only if they were present in the od strain and in the F1 males.

Construction of genetic map of Z chromosome

A genetic map of the Z chromosome was constructed based on the segregation of markers in 55 backcross offspring. Goodness of fit to the expected segregation ratio (1:1) of presence or absence of an amplified product at each marker locus was tested in the 40 BC females by Chi-square (χ2) analysis. The genetic relationship among markers was determined by maximum likelihood (Bailey, 1961) analysis, and the segregation pattern of marker data was analyzed using MAPMAKER version 3.0 with the backcross data as an input file. A minimum LOD score of 3.0 (Log10 of the odds ratio) was used for the pair-wise linkage analysis. Genotyping was carried out with the ERROR DETECTION option, and the recombination values were converted into map distances (in cM) by applying the Kosambi mapping function (Kosambi, 1944).

Results and discussion

Z-linked markers

Out of 560 RAPD primers used in the present study, 13 primers (2.3%) generated Z-linked markers (Table 2). In the backcross females, Z-linked RAPD markers derived from the translucent (od) strain should segregate in a ratio of 1:1 in translucent and normal larvae (Figure 2). Out of the 13 Z-linked RAPD markers, the segregation pattern of 10 markers was consistent with a 1:1 ratio (P (χ2) ⩾0.01), whereas markers OPA-07.1352, OPR-11.1200 OPT-14.583, and TA(CAG)4 deviated slightly from this expected ratio (Table 3).

An example of inheritance and segregation of Z-chromosome-specific RAPD markers generated by primer OPF-02.1240. (a) Parents: Translucent (od) and Pure Mysore and F1 offspring of translucent (od) and Pure Mysore; (b–d) Back cross (BC) offspring of F1 and od. The Z-chromosome-specific marker is indicated by an arrow. M: Lambda HindIII digest size marker. Lanes 1–55 represent the number of BC offspring used for the analysis.

In the present study, out of the 216 SSR loci that were characterized from different silkworm genomic resources (Prasad et al, 2004), two loci, Bmsat95 [(GA)23] and Bmsat208 [(TA)20], showed a Z-linked pattern of inheritance (Table 2) with a segregation that was consistent with the 1:1 ratio (P (χ2) ⩾0.01) (Table 3). The sequence of Bmsat95 showed no homology to any of the sequences in the public databases. Bmsat208 was found to be present in the Z-linked BAC clone 12L3 (Koike et al, 2003) in the intergenic region of Bmtkz, a B. mori tyrosine kinase-like protein, and in BmubcD4, – a B. mori ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme-like protein (Table 4).

Of 43 FISSR primers anchored either at the 5′ or 3′ end that were tested, only one 5′ anchored primer (TA(CAG)4) showed Z linkage (Table 2). The segregation pattern deviated slightly from a 1:1 ratio (P (χ2) ⩾0.01) (Table 3). The sequence of the Z-linked product showed no homology to any of the sequences in the public databases (Table 4).

Construction of Z chromosome genetic map

In the present study, the cumulative segregation data of 16 Z-linked markers of various kinds were used to construct a Z chromosome genetic map. Most of the Z-linked markers were ordered at LOD 3 using the ‘ripple’ command of MAPMAKER (Figure 3). Map length, distance between the markers and gaps were represented in centiMorgan calculated using the Kosambi mapping function. The LOD score for linkage was less than 3 for the largest gap in the map. The average spacing of the Z-linked markers was 20 cM, and the total map covered approximately 334.5 cM. All the RAPD markers, except OPA-07.1352, showed linkage to the phenotypic translucent (od) marker within 55.3 cM. The total length of the map was reduced by 8% from 365 to 334.5 cM when genotyping errors were detected with the MAPMAKER ERROR DETECTION option. The largest reduction was obtained for marker Sat 208 (69%) followed by OPU14 (33%), OPG06, and OPT14 (23%).

The recombination length of the Z chromosome calculated in this study was approximately four times larger than the estimated 80 cM span reported for an RAPD map composed of 18 markers (Yasukochi, 1998), and the 50 cM length of the classical Z chromosome map composed of 15 morphological markers (Fujii et al, 1998). The relatively large gaps by the terminal markers have greatly expanded the total map distance reported here, where relatively high recombination rates were observed (Figure 3). Nevertheless, the 16 markers appeared to be well distributed all along the Z chromosome and covered many gaps and unmapped loci in the preexisting maps. Similar expansion of map length was observed in Apis mellifera, where one of the linkage groups (group I) is more than twice the total length of the D. melanogaster genome (Solignac et al, 2004). Genotyping errors can also result in a significant increase in recombination length (Brzustowicz et al, 1993), but this is unlikely in the present experiments, since the number of genotypes analyzed was few (55) and only reproducible markers that showed the expected pattern of inheritance were scored. Tan and Ma (1998) have theoretically demonstrated that with the addition of new markers, the map length will increase when the marker density is not saturated; conversely, it may decrease when the marker density is saturated. This hypothesis has been supported experimentally for the rice linkage map, which covered 4026.3 cM using 762 markers (Causse et al, 1994), but only 1521.6 cM using 2275 markers (Harushima et al, 1998). In A. mellifera, Solignac et al (2004) observed a decrease in the number of linkage groups and unlinked loci with addition of more markers. Tan et al (2001) also reported an increased length for a silkworm AFLP map composed of 356 markers compared to the RAPD map containing 1018 markers (Yasukochi, 1998), due to large gaps at several locations. Taking these observations together, it is likely that our Z chromosome map has reached an expanded state and the addition of many more markers would reduce the overall map length.

Sequencing and characterizing of Z-linked markers

Of the 16 Z-linked markers, six RAPD, two SSR, and one FISSR markers were sequenced and analyzed for homology with the nucleotide and protein sequences in public databases, including the silkworm WGS sequence. The markers identified several contigs, the sequences of which revealed interesting features (Table 4). The OPU-14.920 sequence was present in two contigs, namely contig52248 and contig147849. Contig52248 showed homology to a part of the adaptin_N domain of the AP-1γ gene of D. melanogaster, which encodes a component of the synaptic vesicle, while contig147849 had no homology with any of the sequences in GenBank. The RAPD OPR-09.1105 was present in contig21903, which showed a stretch of homology to the gene, CG11851, of D. melanogaster, which encodes a product with mannosyltransferase activity involved in amino-acid glycosylation. The OPT-14.583 sequence was identified in contig1401, which shared homology with known ubiquitous non-LTR (long terminal repeat) LINE-1 type repetitive sequences and Bm1 elements of B. mori. Non-LTR LINE-1-like elements are widely distributed in eucaryotes and comprise approximately 30% of the human genome; a recent study has shown that the X chromosome is rich in non-LTR retrotransposon Alu repetitive sequences relative to the Y chromosome and autosomes (Jurka et al, 2004). Bm1 elements are a family of short (130–470 bp) tRNA/U1RNA-derived retroposons or SINEs containing variable 3′ poly (A) tracts, which comprise an estimated 5% of the silkworm genome (Okada et al, 1997). The silkworm Z chromosome has double the repetitive elements of autosomes, a trend which is similar to the X chromosomes in mammals and D. melanogaster. These elements are implicated in X chromosome inactivation and dosage compensation in these organisms (Bailey et al, 2000; Huijser et al, 1987). Since the silkworm is reported to lack dosage compensation (Suzuki et al, 1999), these observations call for further analysis including many more Z-linked genes. In particular, it may be interesting to evaluate the functional significance of such enriched elements on Z chromosome. Since only 2% of molecular information is available for the Z chromosome (Koike et al, 2003), the markers identified in the present study will be particularly useful in the assembly and analysis of Z-linked sequences.

A number of Z-linked characters have significant effects on traits of economic importance for sericulture (Nakada, 1970; Tazima, 1978). In particular, the so-called maturity genes (early maturity, lm; moderate maturity, +Lm, and late maturity, Lm) are said to be major genes controlling the duration of larval life, body weight, and silk fiber length (Tazima, 1978). Homozygous early maturing larvae (lm) are known to make smaller cocoons with short silk fibers, whereas late maturing larvae (Lm) usually grow bigger and produce more silk (Morohoshi, 1949). From population studies carried out in the early 1940s, it is known that several genes that control voltinism modulate the effects of Lm, shifting expected growth rate, larval span, and consequently body weight (Nagatomo, 1942). These genes are, however, difficult to identify without being able to assign map locations and track them precisely in genetic crosses. Further efforts in the development of a high-density silkworm Z chromosome map may aid in the analysis and positional cloning of such important gene(s).

In many groups of Lepidoptera, genes affecting reproductive isolation are sex linked. Interspecific hybridization of many species of wild silk moths has revealed that many reciprocal crosses result in sterile F1 offspring (Jolly et al, 1969; Nagaraju and Jolly, 1985; Shimada and Kobayashi, 1992). Recent studies in other Lepidoptera have shown that the Z-linked genes associated with mating preferences may play a role in host race formation (Sperling, 1994) and speciation (Iyengar et al, 2002). Female F1 offspring produced in interspecific crosses between two species of sexually dimorphic Colias butterflies prefer to mate with males of the paternal species, indicating that Z-linked genes played a role in their speciation (Grula and Taylor, 1980). The Z chromosome analysis in the silk moth, being a genetically and molecularly tractable lepidopteran model system, thus has an important bearing on the understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in reproductive isolation, host race formation, and body weight differences.

W-linked markers

In the present study, screening with 560 random primers, 216 SSR loci, and 43 FISSR primers resulted in the identification of four RAPD markers and four SSR alleles that were W-specific (Figure 4a–e; see Table 5 for W-specific RAPD and SSR primer sequences). Upon sequencing, we found that the W-linked SSR markers were basically allelic variants of sequences derived from WGS contigs covering 11.3 kb (Table 6). Analysis of the contig sequences revealed the presence of different transposable elements making up approximately 26.5% of the sequence; the remaining sequences showed no homology to any of the sequences in the GenBank database. Contig gi54081682 containing the Bmsat153 locus harbored Yamato, a B. mandarina Pao-like LTR retrotransposon (Abe et al, 2001). The Bmsat155 locus was found to be present in Contig gi54071509, which contained a Bm1 repetitive element and a non-LTR retrotransposon, respectively. Contig gi54079028 identified by Bmsat156 contained TREST1, a telomeric repeat sequence (Okazaki et al, 1993). The present study revealed low abundance of W-specific markers, probably because the W chromosome is composed mainly of retrotransposable elements (Abe et al, 1998b, 2000; Sahara et al, 2003), which are also found on other chromosomes suggesting that there is very little W-specific DNA. By using polyploid strains, Hasimoto first showed that the W chromosome carries the major determinant for femaleness in the silkworm (Hasimoto, 1930); subsequent studies carried out by Tazima (1941, 1944) and Hasimoto (1948) with irradiated autosomal fragments harboring genes for phenotypic traits translocated to the W chromosome provided further evidence for its female determining role. More than 90% of the characterized W– chromosome-derived sequence is comprised of retrotransposable elements (Abe et al, 2000; Sahara et al, 2003). This is in contrast to the Z chromosome, where 15.4% of repetitive elements were observed in a contiguous 320 kb sequence (Koike et al, 2003). These results indicate that most of the W chromosome is fairly degraded and lacks genetic activity. This presents a similar situation as in the case of Y chromosomes of D. melanogaster and mammals (Carvalho et al, 2001; Lahn et al, 2001).

Identification of W chromosome-specific RAPD (a–d) and SSR (e) markers; (a) OPA-09, (b) OPC-09, (c) OPI-18, (d) OPM-06, and (e) Bmsat153, Bmsat155, Bmsat156, and Bmsat159 in translucent (od) females (♀), F1 males (♂), F1 females (♀), and Pure Mysore (PM) male (♂). Arrow indicates W-specific markers. M: Lambda HindIII digest size marker.

The RAPD markers identified in the present study will aid in retrieving additional contigs for further analysis and characterization of W chromosome-specific sequences, which will augment the ongoing efforts to identify the putative female determining gene(s). These include a set of sex-limited Ze strains that carry reciprocal translocation between Z and the third chromosome, which also contains a small portion of the W chromosome that determines femaleness (Hasimoto, 1953).

Comparative genetic mapping is an effective tool for the study of genome evolution in phylogenetically distant species that represent key stages in insect evolution. Using both physical and genetic methods, orthologous W- and Z chromosome genes of the silkworm can be identified and mapped in other insect species or in other higher order organisms. The Z- and W-linked markers, together with those reported by earlier studies, provide the much needed genetic resources to address these issues.

References

Abe H, Kanehara M, Terada T, Ohbayashi F, Shimada T, Kawai S et al (1998a). Identification of novel random amplified polymorphic DNAs (RAPDs) on the W chromosome of the domesticated silkworm, Bombyx mori, and the wild silkworm, B. mandarina, and their retrotransposable element-related nucleotide sequences. Genes Genet Syst 73: 243–254.

Abe H, Ohbayashi F, Shimada T, Sugasaki T, Kawai S, Mita K et al (2000). Molecular structure of a novel gypsy-Ty3-like retrotransposon Kabuki and nested retrotransposable elements on the W chromosome of the silkworm Bombyx mori. Mol Gen Genet 263: 916–924.

Abe H, Ohbayashi F, Shimada T, Sugasaki T, Kawai S, Oshiki T (1998b). A complete full-length non-LTR retrotransposon, BMC1, on the W chromosome of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Genes Genet Syst 73: 353–358.

Abe H, Ohbayashi F, Sugasaki T, Kanehara M, Terada T, Shimada T et al (2001). Two novel Pao-like retrotansposons (Kamikaze and Yamato) of the silkworm Bombyx mori and B. mandarina and common structural features of Pao-like elements. Mol Genet Genomics 265: 375–385.

Abe H, Shimada T, Kawai S, Ohbayashi F, Harada T, Yokoyama T et al (1996). Nucleotide sequence of the random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) on the W chromosome of the domesticated silkworm, Bombyx mori (Lepidoptera: Bombycidae). Appl Entomol Zool 31: 633–637.

Abe H, Shimada T, Yokoyama T, Oshiki T, Kobayashi M (1995). Identification of random amplified polymorphic DNAs on the W chromosome of the Chinese 137 strain of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. J Seric Sci Jpn 64: 19–22.

Bailey JA, Carrel L, Chakravarti A, Eichler EE (2000). Molecular evidence for relationship between LINE-1 elements and X chromosome inactivation: the Lyon repeat hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 6634–6639.

Bailey NTJ (1961). Introduction to the Mathematical Theory of Genetic Linkage. Clarendon press: Oxford, UK.

Brzustowicz LM, Merette C, Xie X, Townsend L, Gilliam TC, Ott J (1993). Molecular and statistical approaches to the detection and correction of errors in genotype databases. Am J Hum Genet 53: 1137–1145.

Bull JJ (1983). Evolution of Sex-Determining Mechanisms. Menlo Park: Benjamin-Cummings.

Carvalho AB (2002). Origin and evolution of the Drosophila Y chromosome. Curr Opin Gen Dev 12: 664–668.

Carvalho AB, Dobo BA, Vibranovski MD, Clark AG (2001). Identification of five new genes on the Y chromosome of the Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 13225–13230.

Causse MA, Fulton TM, Cho YG, Ahn SN, Chunwongse J, Wu K et al (1994). Saturated molecular map of the rice genome based on an interspecific backcross population. Genetics 138: 1251–1274.

Charlesworth B, Charlesworth D (2000). The degeneration of Y-chromosomes. Phil Trans R Soc Lond B 355: 1563–1572.

Chippindale AK, Rice WR (2001). Y chromosome polymorphism is a strong determinant of male fitness in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 5677–5682.

Fujii H, Banno Y, Doira H, Kihara H, Kawaguchi Y (1998). Genetical Stocks and Mutations of Bombyx mori: Important Genetic Resources. Institute of Genetic Resources, Kyushu University: Fukuoka, Japan.

Goldsmith MR, Shimada T, Abe H (2005). Genetics and genomics of the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Ann Rev Entomol 50: 71–100.

Grula JW, Taylor Jr OR (1980). The effect of X-chromosome inheritance on mate selection behaviour in the sulfur butterflies, Colias eurytheme and C. philodice. Evolution 34: 688–695.

Guttman DS, Charlesworth D (1998). An X-linked gene with a degenerate Y-linked homologue in a dioecious plant. Nature 393: 263–266.

Harushima Y, Yano M, Shomura A, Sato M, Shimano T, Kuboki Y et al (1998). A high-density rice genetic linkage map with 2275 markers using a single F2 population. Genetics 148: 479–494.

Hasimoto H (1930). Heredity superfluous legs in the silkworm. Jpn J Genet 6: 45–54.

Hasimoto H (1948). Sex-limited zebra, an X-ray mutation in the silkworm. J Seric Sci Jpn 16: 62–64 (in Japanese).

Hasimoto H (1953). Genetical studies of Bombyx mori L. on the lethal gene which affects the male. J Seric Sci Jpn 22: 200–204 (in Japanese with Esperanto summary).

Huijser P, Hennig W, Dijkhof R (1987). Poly (dC-dA/dG-dT) repeats in the Drosophila genome: a key function for dosage compensation and position effects? Chromosoma 95: 209–215.

Iyengar VK, Reeve HK, Eisner T (2002). Paternal inheritance of a female moth's mating preference. Nature 419: 830–832.

Jegalian K, Page DC (1998). A proposed path by which genes common to mammalian X and Y-chromosomes evolve to become X inactivated. Nature 394: 776–780.

Jolly MS, Narasimhanna MN, Sinha SS, Sen SK (1969). Interspecific hybridization in Antheraea. Ind J Hered 1: 45–48.

Jurka J, Kohany O, Pavlicek A, Kapitonov VV, Jurka MV (2004). Duplication, co-clustering, and selection of human Alu retrotransposons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 1268–1272.

Koike Y, Mita K, Suzuki MG, Maeda S, Abe H, Osoegawa K et al (2003). Genomic sequence of a 320-kb segment of the Z chromosome of Bombyx mori containing a kettin ortholog. Mol Genet Genom 269: 137–149.

Kosambi DD (1944). The estimation of map distances from recombination values. Ann Eugen 12: 172–175.

Lahn BT, Pearson NM, Jagalian K (2001). The human Y chromosome, in the light of evolution. Nat Rev Genet 2: 207–216.

Mita K, Kasahara M, Sasaki S, Nagayasu Y, Yamada T, Kanamori H et al (2004). The genome sequence of silkworm, Bombyx mori. DNA Res 11: 27–35.

Mita K, Morimyo M, Okano K, Koike Y, Nohata J, Kawasaki H et al (2003). The construction of an EST database for Bombyx mori and its application. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 14121–14126.

Morohoshi S (1949). Developmental Mechanism in Bombyx mori. Meibundo: Tokyo.

Nagaraja GM, Nagaraju J (1995). Genome fingerprinting of the silkworm, Bombyx mori, using random arbitrary primers. Electrophoresis 16: 1633–1638.

Nagaraju J, Goldsmith MR (2002). Silkworm genomics-Progress and prospects. Curr Sci 83: 415–425.

Nagaraju J, Jolly MS (1985). Interspecific hybrids of Antheraea pernyi and A. roylei – a cytogenetic reassessment. Theo Appl Genet 72: 269–273.

Nagaraju J, Kathirvel M, Subbaiah EV, Muthulakshmi M, Kumar LD (2002). FISSR-PCR: a simple and sensitive assay for high throughput genotyping and genetic mapping. Mol Cell Probes 16: 67–72.

Nagatomo T (1942). On the inheritance of voltinism in the silkworm. J Seric Sci Jpn 13: 114–115.

Nakada T (1970). Researches on the sex-linked inheritance of the cocoon weight of reciprocal crossings. J Fac Agric Hokkaido Univ 56: 348–358.

Ohbayashi F, Shimada T, Sugasaki T, Kawai S, Yokoyama T, Oshiki T et al (1996). A common random amplified polymorphic DNA in the silkworm, Bombyx mori is shared by W-chromosomes onto which the normal marking, Sable, and Black genes are translocated respectively. J Seric Sci Jpn 65: 395–398 (in Japanese).

Ohno S (1967). Sex Chromosomes and Sex-Linked Genes. Springer: Berlin.

Okada N, Hamada M, Ogiwara I, Ohshima K (1997). SINEs and LINEs share common 3′ sequences: a review. Gene 205: 229–243.

Okazaki S, Tsuchida K, Maekawa H, Ishikawa H, Fujiwara H (1993). Identification of a pentanucleotide telomeric sequence, (TTAGG)n, in the silkworm Bombyx mori and in other insects. Mol Cell Biol 13: 1424–1432.

Prasad MD, Muthulakshmi M, Madhu M, Sunil Archak, Mita K, Nagaraju J (2004). Survey and analysis of microsatellites in the silkworm, Bombyx mori: frequency, distribution, mutations, marker potential and their conservation in heterologous species. Genetics 169: 197–214.

Reddy KD, Abraham EG, Nagaraju J (1999). Micro satellites of the silkworm, Bombyx mori: abundance, polymorphism and strain characterization. Genome 42: 1057–1065.

Sahara K, Yoshido A, Kawamura N, Onuma A, Abe H, Mita K et al (2003). W-derived BAC probes as a new tool for identification of the W chromosome and its aberrations in Bombyx mori. Chromosoma 112: 48–55.

Shimada T, Kobayashi M (1992). Fertility of F1 hybrids between Antheraea yamamai (Guerin-Meneville) and Antheraea pernyi (G-M). In: Akai H, Kato Y, Kiuchi M, Kobayashi J (eds) Wild Silkmoths'91, International Society of Wild Silkmoths: Japan. pp 186–195.

Skaletsky H, Kuroda-kawaguchi T, Minx PJ, Cordum HS, Hiller L, Brown LG et al (2003). The male-specific region of the human Y chromosome is a mosaic of discrete sequence classes. Nature 423: 825–837.

Solignac M, Vautrin D, Baudry E, Mougle F, Loiseau A, Cornuet JM (2004). A microsatellite-based linkage map of the Honeybee, Apis mellifera L. Genetics 167: 253–262.

Sperling F (1994). Sex-linked genes and species differences in lepidoptera. Can Entomol 126: 807–818.

Sturtevant AH (1915). No crossing over in the female of the silkworm moth. Am Nat 49: 42–44.

Suzuki MG, Shimada T, Kobayashi M (1998). Absence of dosage compensation at the transcriptional level of a sex-linked gene in a female heterogametic insect, Bombyx mori. Heredity 81: 275–283.

Suzuki MG, Shimada T, Kobayashi M (1999). Bmkettin, homologue of the Drosophila kettin gene, is located on the Z chromosome in Bombyx mori and is not dosage compensated. Heredity 82: 170–179.

Tan YD, Ma R-L (1998). Estimates of lengths of genome and chromosomes of rice using molecular markers. J Biomath 13: 1022–1027 (Chinese).

Tan YD, Wan C, Zhu Y, Lu C, Xiang Z, Deng HW (2001). An amplified fragment length polymorphism map of the silkworm. Genetics 157: 1277–1284.

Tazima Y (1941). A simple method of sex discrimination by means of larval markings in Bombyx mori. J Seric Sci Jpn 12: 184–188 (in Japanese).

Tazima Y (1944). Studies on chromosome aberrations in the silkworm. II. Translocation involving second and W-chromosomes. Bull Seric Exp Stn 12: 109–181 (in Japanese with English summary).

Tazima Y (1964). The Genetics of the Silkworm. Logos press: London and Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

Tazima Y (1978). The Silkworm: an Important Laboratory Tool. Kodansha Ltd: Tokyo, Japan. pp 53–81.

Traut W (1977). A study of recombination, formation of chiasmata and synaptonemal complexes in female and male meiosis of Ephestia kuehniella (Lepidoptera). Genetics 47: 135–142.

Yasukochi Y (1998). A dense genetic map of the silkworm, Bombyx mori, covering all chromosomes based on 1018 molecular markers. Genetics 150: 1513–1525.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professors M Goldsmith and T Shimada for their critical reading of the manuscript and valuable suggestions. We are grateful to Dr K Mita for sharing sequence data. GM is the recipient of a Postdoctoral fellowship from the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India. VS is a recipient of a Senior Research Fellowship from the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research, Department of Science and Technology, Government of India. The work was supported by grants to JN from the Department of Biotechnology, India-Japan Cooperative Science Programme (IJCSP), and International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Nagaraja, G., Mahesh, G., Satish, V. et al. Genetic mapping of Z chromosome and identification of W chromosome-specific markers in the silkworm, Bombyx mori. Heredity 95, 148–157 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800700

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.hdy.6800700

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Application of biotechnology in sericulture: Progress, scope and prospect

The Nucleus (2022)

-

Novel female-specific splice form of dsx in the silkworm, Bombyx mori

Genetica (2011)

-

A rearrangement of the Z chromosome topology influences the sex-linked gene display in the European corn borer, Ostrinia nubilalis

Molecular Genetics and Genomics (2011)

-

Isolation and characterization of sex chromosome rearrangements generating male muscle dystrophy and female abnormal oogenesis in the silkworm, Bombyx mori

Genetica (2007)