Abstract

Objective:

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) reduces plasma glucose and triglycerides, and increases free fatty acid oxidation in animal models of diabetes. The aim of the present study was to assess the relationships of serum FGF21 with glucose oxidation (GOx) and lipid oxidation (LOx) in the baseline and insulin-stimulated conditions in lean and obese subjects.

Design:

Cross-sectional study.

Subjects:

Eighty-four subjects with normal glucose tolerance, 42 lean (body mass index (BMI) <25 kg m−2) and 42 overweight or obese (BMI between 25 and 40 kg m−2).

Measurements:

Euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp and indirect calorimetry in the baseline state and during last 30 min of the clamp. The change in respiratory quotient (ΔRQ) in response to insulin was used as a measure of metabolic flexibility. Serum FGF21 was determined in the baseline state and after the clamp.

Results:

Obese subjects had higher LOx in the baseline and insulin-stimulated conditions, lower insulin-stimulated GOx and ΔRQ (all P<0.05). Fasting serum FGF21 did not differ between the groups. Insulin infusion resulted in an increase in serum FGF21 in the obese (P=0.0001), but not in the lean group (P=0.76). Postclamp serum FGF21 was higher in the obese subjects (P=0.0007). In this group, postclamp FGF21 was related to LOx during the clamp (r=0.32, P=0.044), change in GOx and LOx in response to insulin (r=−0.44, P=0.005; r=0.47, P=0.002; respectively) and ΔRQ (r=−0.50, P=0.001).

Conclusions:

An increase in serum FGF21 in response to insulin in obese subjects might represent inappropriate response, possibly associated with metabolic inflexibility in obesity and insulin resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21), a member of FGF family, has been demonstrated to exert important metabolic actions.1 It increases glucose uptake by adipocytes, independently and additively to insulin.1 Administration of FGF21 to diabetic rodents reduces plasma glucose and triglycerides (TG), and increases insulin sensitivity.1 FGF21-transgenic mice demonstrate lower glucose levels, less liver fat, more brown adipose tissue and better insulin sensitivity in comparison with their wild-type littermates, and are resistant to diet-induced obesity.1 Some studies have provided evidence that the important mechanism of beneficial FGF21 action involves an increase in fatty acid oxidation, possibly through an induction of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator protein 1α (PGC1α)2, 3, 4 and also a rise in resting energy expenditure (REE).5

In humans, circulating FGF21 is increased in insulin-resistant states, such as obesity,6 impaired glucose tolerance,7 type 2 diabetes7, 8 and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.9 An inverse relationship with whole-body insulin sensitivity and a positive correlation with hepatic insulin resistance have also been reported.7 In another study, no association with insulin sensitivity has been found, although serum FGF21 has been observed to be related to measures of adiposity, lipid parameters and γ-glutamyltransferase activity.10 It has been hypothesized that an increase in circulating FGF21 in insulin-resistant conditions may represent a resistance to this factor or a compensatory response.6 In line with this, obese mice exhibit an impaired response to exogenous FGF21.(ref.11) However, the concept of FGF21-resistance in obesity has been challenged, as ob/ob and diet-induced obese mice were found to demonstrate preserved metabolic response to exogenous FGF21, and glucose-lowering and weight-loss effects of the compound were even enhanced in these animals in comparison with their lean littermates.12

The regulation of circulating FGF21 levels is complex and not completely understood. Liver and circulating FGF21 were induced by fasting and high-fat/low-carbohydrate ketogenic diet.2 It has been demonstrated that free fatty acids (FFA) increase circulating FGF21 concentration, thus potentially explaining its elevated levels in fasting, but also in obesity and type 2 diabetes.13 Hyperinsulinemia also increased circulating FGF21(refs 13, 14, 15, 16) as well as its adipose tissue and muscle expression in humans.14, 16 In another study, insulin was reported to have a relatively minor role in the regulation of circulating FGF21 under physiological conditions.17 In patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes, short-term subcutaneous insulin infusion decreased plasma FGF21.(ref. 18) The issue whether the regulation of circulating FGF21 by insulin is dependent on overweight/obesity has not been extensively studied so far.

Insulin resistance is associated with the so-called ‘metabolic inflexibility’, that is, impaired switch from lipid oxidation (LOx) to glucose oxidation (GOx) in response to insulin,19 as assessed by an impaired increase in respiratory quotient (RQ) in response to insulin. Given the actions of FGF21, it is a potential attractive candidate for the modulation of metabolic flexibility. However, there are limited data on the relation of FGF21 with GOx and LOx in humans.

The aim of the present study was to assess the relationships of serum FGF21 with GOx and LOx in the baseline and insulin-stimulated conditions in lean and obese subjects.

Subjects and methods

Subjects

We examined 84 subjects with normal glucose tolerance, 42 lean (body mass index (BMI) <25 kg m−2, 14 males and 28 females) and 42 overweight or obese (BMI >25 kg m−2, 9 males and 33 females), matched for age. None of the participants had morbid obesity, ischemic heart disease, hypertension, peripheral vascular disease, infection or any other serious medical problem; all were non-smokers and none was taking drugs known to affect carbohydrate or lipid metabolism. Glucose tolerance status was estimated on the basis of an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) according to WHO criteria, and all participants had normal glucose tolerance. All analyses were performed after an overnight fast. In women, all analyses were performed between day 3 and 5 of their menstrual cycle. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University, Bialystok, Poland. All participants gave written informed consent before entering the study.

Anthropometric measurements

Anthropometric measurements were performed as previously described.20 The BMI was calculated as body weight × height−2 and expressed in kg × m−2. The waist circumference was measured at the smallest circumference between the rib cage and the iliac crest, with the subject in the standing position. The percent of body fat was assessed by bioelectric impedance analysis using a Tanita TBF-511 Body Fat Analyzer (Tanita Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

Insulin sensitivity

Insulin sensitivity was evaluated with the euglycemic hyperinsulinemic clamp technique, according to DeFronzo et al.,21 as described previously.20, 22 In the morning of the study, two venous catheters were inserted into antecubital veins, one for the infusion of insulin and glucose, and the other in the contralateral hand for blood sampling, with that hand heated to ∼60 °C. Insulin (Actrapid HM, Novo Nordisk, Copenhagen, Denmark) was given as a primed-continuous intravenous infusion for 120 min at 40 mU m−2 min−1, resulting in constant hyperinsulinemia of approximately−100 μIU ml−1. Arterialized blood glucose was obtained every 5 min, and 20% dextrose (1.11 mol l−1) infusion was adjusted to maintain plasma glucose levels at 5 mmol l−1. The rate of whole-body glucose uptake (M value) was calculated as the mean glucose infusion rate during the last 40 min of the clamp period, corrected for glucose space and normalized per kg fat-free mass.

Indirect calorimetry

In the baseline conditions, before the clamp (for 30 min) and during the last 30 min of the clamp, indirect calorimetry was performed using the ventilated hood technique (Oxycon Pro, Viasys GmbH—Erich Jaeger, Hochberg, Germany), as described previously.22 The measurements were taken while the subjects were lying in the supine position. The average gas exchange recorded over the two 30-min periods was used to calculate REE, and the rates of GOx and LOx. Total glucose metabolism was calculated from the clamp study. The non-oxidative glucose metabolism was calculated in insulin-stimulated conditions by subtracting GOx from total glucose metabolism. The change in RQ (ΔRQ) in response to insulin was used as a measure of metabolic flexibility.

Biochemical analyses

Plasma glucose was measured immediately by the enzymatic method using a glucose analyzer YSI 2300 STAT Plus (YSI Inc., Yellow Springs, OH, USA). Serum insulin was determined with a monoclonal immunoradiometric assay (Medgenix Diagnostics, Fleunes, Belgium). Serum total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein–cholesterol and TG were assessed by enzymatic methods (Cormay, Warsaw, Poland), and low-density lipoprotein–cholesterol was calculated with Friedewald’s formula. Serum FFAs were assayed using a commercially available kit (Wako Chemicals, Richmond, VA, USA). Serum FGF21 concentration in all subjects was measured before and after the clamp by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (BioVendor Laboratory Medicine, Modrice, Czech Republic), with sensitivity of 7 pg ml−1, and intra-assay and inter-assay coefficients of variation below 3.7% and 3.9%, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The statistics were performed with the STATISTICA 8.0 software (Krakow, Poland). Parameters with abnormal distribution (FGF21, insulin, TG, FFA) were log-transformed before analyses. In the Results, these parameters were again transformed to absolute values for the purpose of data presentation. Serum FGF21 levels before and after the clamp were compared using a paired Student’s t-test. Differences between the groups were estimated with an unpaired Student’s t-test. The relationships between variables were evaluated using the Pearson’s product–moment correlation analysis and multiple regression analysis. The level of significance was accepted at P<0.05.

Results

The clinical characteristics of the study groups are presented in Table 1. By definition, the obese group had higher BMI, waist circumference and the percent of body fat (all P<0.0001). Also, the obese group had higher postload glucose, fasting and postload insulin (all P<0.001) and TG (P=0.002), and lower high-density lipoprotein–cholesterol (P=0.036) (Table 1).

During the clamp, no difference was observed in steady-state insulin (lean, 99.74±24.69 vs obese, 107.52±31.00 μIU ml−1; NS) and FFA (lean, 0.14±0.08 vs obese 0.18±0.16 mmol l−1; NS) between the groups. The obese group had lower insulin sensitivity (P<0.001), non-oxidative glucose metabolism (P=0.002), RQ and GOx during the clamp (both P=0.003), and higher LOx in the baseline state and during the clamp (P=0.02 and P=0.01; respectively). Metabolic flexibility was impaired in this group (P=0.02) (Table 2). REE was higher in the obese group both in the baseline conditions and during the clamp (P<0.001 and P=0.001; respectively) (Table 2). In the baseline state, this difference remained significant after calculating the REE/fat-free mass ratio (30.12±3.37 vs 32.97±4.28 kcal per day per kg fat-free mass; P=0.0016).

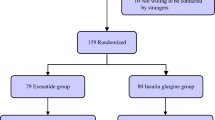

Fasting serum FGF21 did not differ between the lean and obese groups. Hyperinsulinemia resulted in an increase in serum FGF21 in the obese (P=0.0001), but not in the lean group (P=0.76). In consequence, postclamp serum FGF21 was higher in the obese group (P=0.0007) (Figure 1). The increase in FGF21 during the clamp was also present when overweight (n=21, 126.15±110.96 vs 158.67±105.60 ng l−1; P=0.013) and obese subjects (n=21, 137.78±104.74 vs 222.11±144.63 ng l−1; P=0.003) were analyzed separately. In all the conditions, no difference was observed in serum FGF21 between men and women. No correlations were found between basal or postclamp FGF21 and steady-state insulin or FFA in the entire group or within the subgroups of lean and overweight/obese subjects.

In the obese group, postclamp FGF21 was related to high-density lipoprotein–cholesterol (r=−0.32, P=0.047), RQ and LOx during the clamp (r=−0.32 and r=0.32; respectively, both P=0.044), change in GOx and LOx in response to insulin (r=−0.44, P=0.005; Figure 2a and r=0.47, P=0.002; Figure 2b, respectively; that is, the higher postclamp FGF21, the lower increase in GOx and lower decrease in LOx during the clamp) and ΔRQ (r=−0.50, P=0.001) (Figure 2c). These correlations were not observed in the lean group. No relationships between the changes in FGF21 and those in the substrate oxidation rates were noted.

In the obese group, after adjustment for gender, BMI and fasting insulin, associations with ΔGOx (β=−0.37, P=0.016), ΔLOx (β=0.43, P=0.006) and ΔRQ (r=−0.44, P=0.004) were still significant, whereas those with RQ and LOx during the clamp were close to significant (β=−0.29, P=0.08 and β=0.29, P=0.08; respectively).

Table 3 shows correlations of fasting and postclamp serum FGF21 with other estimated parameters in the entire study group. These relationships were not significant when lean and obese subjects were analyzed separately.

Discussion

The main finding of our study was that serum FGF21 was increased in response to insulin infusion in overweight/obese, but not in lean subjects, and that it was associated with substrate oxidation in insulin-stimulated conditions.

Fasting serum FGF21 did not differ between lean and overweight/obese subjects. This result is not consistent with other studies,6, 15 which reported an increase in circulating, fasting FGF21 in obesity. This difference may be potentially explained by much younger age in our study group and relatively uncomplicated obesity. Also, in the study of Mraz et al.,15 the mean BMI in the obese group was within morbid obesity range, being substantially higher than in our study.

Serum FGF21 was increased in response to insulin infusion in overweight/obese subjects, but not in lean individuals. Upregulation of circulating FGF21 by insulin has been reported in previous studies.13, 14, 15, 16 Insulin upregulates adipose tissue FGF21 mRNA expression,16 and this may be a potential mechanism underlying the increased serum FGF21 observed in the obese subjects. In a study performed by Vienberg et al.,16 the effect of insulin infusion on serum FGF21 was observed despite the fact that obesity was an exclusion criterion.16 However, our data are in agreement with those of Mraz et al.,15 who observed no increase in serum FGF21 in lean subjects. In their study, a rise was found only in obese subjects with type 2 diabetes.15 Obese subjects with normal glucose tolerance were not examined in that particular experiment,15 in contrast to our study.

In the current study, both fasting and postclamp FGF21 were positively related to REE, and postclamp FGF21 was also related to substrate oxidation in insulin-stimulated conditions, particularly in the obese subjects. No association between FGF21 and REE was reported by Vienberg et al.,16 possibly because of different inclusion criteria than in our study, as mentioned above.

In the fasting state, it is favorable to rely mainly on fatty acid oxidation, as it may prevent ectopic fat accumulation in the liver, muscles and other tissues. However, in response to insulin, GOx increases and fatty acid oxidation decreases rapidly. This process is important for the postprandial glucose metabolism and, as already mentioned, is called metabolic flexibility.19 The obese subjects in our study demonstrated impaired metabolic flexibility. In consequence, in insulin-stimulated conditions their GOx rate was lower and LOx rate was higher in comparison with lean subjects.

In our opinion, it is important that FGF21 is associated with substrate oxidation mainly in insulin-stimulated conditions and mainly in obesity. An increase in fatty acid oxidation is the well-described action of FGF21 ,and we think that the above correlations, which show that FGF21 increases with a rise in LOx, indirectly suggest that this action is preserved. Thus, our results may be interpreted in line with the previously mentioned study, showing normal metabolic response to FGF21 in two animal models of obesity and insulin resistance.12 In the present study, FGF21 was directly associated with LOx in the insulin-stimulated conditions, that is, when maintaining fatty acid oxidation might not necessarily be beneficial. Indeed, postclamp FGF21 was inversely related to metabolic flexibility. Thus, we propose the hypothesis that obesity and insulin resistance represent a state of inappropriate FGF21 regulation, rather than FGF21-resistance. This may be of potential importance, as hyperinsulinemia obtained during the clamp may mimic postprandial insulin response in obese subjects.

Our study has its limitations. We interpret our results on the basis of correlative analysis, referring to the previously known FGF21 metabolic actions. However, as there are limited human data on the relationship between FGF21 and substrate oxidation, we believe that our results may be useful for further studies.

In conclusion, an increase in serum FGF21 in response to insulin in obese subjects might represent inappropriate response, possibly associated with metabolic inflexibility in obesity and insulin resistance.

References

Kharitonenkov A, Shiyanova TL, Koester A, Ford AM, Micanovic R, Galbreath EJ et al. FGF-21 as a novel metabolic regulator. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 1627–1635.

Badman MK, Pissios P, Kennedy AR, Koukos G, Flier JS, Maratos-Flier E . Hepatic fibroblast growth factor 21 is regulated by PPARα and is a key mediator of hepatic lipid metabolism in ketotic states. Cell Metab 2007; 5: 426–437.

Potthoff MJ, Inagaki T, Satapati S, Ding X, He T, Goetz R et al. FGF21 induces PGC1α and regulates carbohydrate metabolism during the adaptive starvation response. PNAS 2009; 106: 10853–10858.

Inagaki T, Dutchak P, Zhao G, Ding X, Gautron L, Parameswara V et al. Endocrine regulation of the fasting response by PPARα-mediated induction of fibroblast growth factor 21. Cell Metab 2007; 5: 415–425.

Xu J, Lloyd DJ, Hale C, Stanislaus S, Chen M, Sivits G et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 reverses hepatic steatosis, increases energy expenditure, and improves insulin sensitivity in diet-induced obese mice. Diabetes 2009; 58: 25–259.

Zhang X, Yeung DC, Karpisek M, Stejskal D, Zhou ZG, Liu F et al. Serum FGF21 levels are increased in obesity and are independently associated with the metabolic syndrome in humans. Diabetes 2008; 57: 1246–1253.

Chavez AO, Molina-Carrion M, Abdul-Ghani M, Folli F, DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D . Circulating fibroblast growth factor 21 is elevated in impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes and correlates with muscle and hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes Care 2009; 32: 1542–1546.

Chen WW, Li L, Yang GY, Li K, Qi XY, Zhu W et al. Circulating FGF-21 levels in normal subjects and in newly diagnosed patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes 2008; 116: 65–68.

Dushay J, Chui PC, Gopalakrishnan GS, Varela-Rey M, Crawley M, Fisher FM et al. Increased fibroblast growth factor 21 in obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology 2010; 139: 456–463.

Li H, Bao Y, Xu A, Pan X, Lu J, Wu H et al. Serum fibroblast growth factor 21 is associated with adverse lipid profiles and γ-glutamyltransferase but not insulin sensitivity in Chinese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2009; 94: 2151–2156.

Fisher FM, Chui PC, Antonellis PJ, Bina HA, Kharitonenkov A, Flier JS et al. Obesity is a fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21)-resistant state. Diabetes 2010; 59: 2781–2789.

Hale C, Chen MM, Stanislaus S, Chinookoswong N, Hager T, Wang M et al. Lack of overt FGF21 resistance in two mouse models of obesity and insulin resistance. Endocrinology 2012; 153: 69–80.

Mai K, Andres J, Biedasek K, Weicht J, Bobbert T, Sabath M et al. Free fatty acids link metabolism and regulation of insulin-sensitizing fibroblast growth factor 21. Diabetes 2009; 58: 1532–1538.

Hojman P, Pedersen M, Nielsen AR, Krogh-Madsen R, Yfanti C, Akerstrom T et al. Fibroblastgrowth factor 21 is induced in human skeletal muscles by hyperinsulinemia. Diabetes 2009; 58: 2797–2801.

Mraz M, Bartlova M, Lacinova Z, Michalsky D, Kasalicky M, Haluzikova D et al. Serum concentrations and tissue expression of a novel endocrine regulator fibroblast growth factor-21 in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity. Clin Endocrinol 2009; 71: 369–375.

Vienberg SG, Brons C, Nilsson E, Astrup A, Vaag A, Andersen B . Impact of short-term high-fat feeding and insulin-stimulated FGF21 in subjects with low birth weight and controls. Eur J Endocrinol 2012; 167: 49–57.

Mai K, Bobbert T, Groth C, Assmann A, Meinus S, Kraatz J et al. Physiological modulation of circulating FGF21: relevance of free fatty acids and insulin. Am J Physiol 2010; 299: E126–E130.

Yang M, Dong J, Liu H, Li L, Yang G . Effects of short-term continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion on fasting plasma fibroblast growth factor-21 levels in patients with newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e26359.

Kelley DE . Skeletal muscle fat oxidation: timing and flexibility are everything. J Clin Invest 2005; 115: 1699–1702.

Karczewska-Kupczewska M, Kowalska I, Nikołajuk A, Adamska A, Zielińska M, Kamińska N et al. Circulating brain-derived neurotrophic factor concentration is downregulated by intralipid/heparin infusion or high-fat meal in young healthy male subjects. Diabetes Care 2012; 35: 358–362.

DeFronzo RA, Tobin JD, Andres R . Glucose clamp technique: a method for quantifying insulin secretion and resistance. Am J Physiol 1979; 237: E214–E223.

Karczewska-Kupczewska M, Strączkowski M, Adamska A, Nikołajuk A, Otziomek E, Górska M et al. Insulin sensitivity, metabolic flexibility, and serum adiponectin concentration in women with anorexia nervosa. Metabolism 2010; 59: 473–477.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Grant UDA-POIG.01.03.01-00-128/08, from the Program Innovative Economy 2007–2013, part-financed by the European Union within the European Regional Development Fund, and grant 3-50689 from Medical University of Białystok, Poland.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Strączkowski, M., Karczewska-Kupczewska, M., Adamska, A. et al. Serum fibroblast growth factor 21 in human obesity: regulation by insulin infusion and relationship with glucose and lipid oxidation. Int J Obes 37, 1386–1390 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.10

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2013.10

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Deficiency of fibroblast growth factor 21 aggravates obesity-induced atrophic responses in skeletal muscle

Journal of Inflammation (2019)

-

Fasting and glucose induced thermogenesis in response to three ambient temperatures: a randomized crossover trial in the metabolic syndrome

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2018)

-

Opposite alterations in FGF21 and FGF19 levels and disturbed expression of the receptor machinery for endocrine FGFs in obese patients

International Journal of Obesity (2015)

-

Obesity and carotid artery remodeling

Nutrition & Diabetes (2015)

-

The role of the Nrf2/Keap1 pathway in obesity and metabolic syndrome

Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders (2015)