Abstract

Objective:

The Virginia lines of chickens have resulted from more than 55 generations of artificial selection for low (LWS) or high (HWS) juvenile body weight. We hypothesized that the relative hyperphagia and greater body weight in juvenile HWS chickens are associated with altered fatty acid oxidation efficiency and metabolic flexibility in tissues associated with energy sensing and storage, and relative cellular hypertrophy in white adipose tissue.

Methods:

Hypothalamus, liver, pectoralis major, gastrocnemius, abdominal fat, clavicular fat and subcutaneous fat were collected from the juvenile (56–65 days old) LWS and HWS chickens for metabolic, gene expression and histological assays.

Results:

The HWS chickens had reduced fatty acid oxidation efficiency in abdominal fat (P<0.0001) and reduced rates of oxidation in abdominal fat and gastrocnemius (P<0.0001) as compared with the LWS. There was reduced citrate synthase activity in white adipose tissue (P<0.0001) and greater metabolic inflexibility in skeletal muscle (P=0.006) of the HWS compared with the LWS. Greater pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) and forkhead box O1A (FoxO1) mRNA were found in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue of 56-day-old HWS than LWS. Expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ (PPARγ) in all adipose tissue depots was greater (P<0.05) in LWS than in HWS chickens. The HWS chickens had larger (P<0.0001) and fewer (P<0.0001) adipocytes per unit area than the LWS.

Conclusion:

Compared with the LWS, the HWS chickens have impaired metabolic flexibility and fatty acid oxidation efficiency due to greater pyruvate dehydrogenase activity to accommodate the influx of acetyl-CoA from fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue. These metabolic adaptations can be linked to differences in gene expression regulation, adipocyte cellularity and body composition between the lines, which may provide valuable insight into metabolic disorders in other species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Virginia lines of chickens have resulted from long-term (56 generations) divergent selection for low (LWS) or high (HWS) juvenile (56 days of age) body weight, respectively. Selection for body weight, with a more than 10-fold difference in body weight now observed between the lines at selection age, led to correlated responses in feeding behavior and body composition, whereby the LWS are relatively lean and hypophagic, whereas the HWS are heavier and hyperphagic as juveniles.1, 2, 3, 4 The severely hypophagic LWS individuals do not initiate feeding after hatch and die shortly after resorption of the yolk sac, whereas the ones that survive show delayed sexual maturity.2 Juvenile HWS have 10-fold greater abdominal fat (as a percentage of body weight) and adult females have 5% more total body fat than their respective LWS contemporaries.1,3,5, 6, 7 More than a decade of research on the feeding behavior of these lines has revealed a differential response in food intake and hypothalamic chemistry to appetite-associated neurotransmitters and relative hyperphagia in the HWS chicks.8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16 Regardless of the feeding state (fasted vs fed), 28-day old LWS chickens displayed greater lipolytic capacities in abdominal fat as compared with their HWS counterparts, providing evidence to help explain the slower rate of fat accumulation in the LWS chicks.17 Administration of oral nutrient boluses was associated with minimal fat deposition in the LWS, which occurred primarily through hypertrophy, whereas adipose tissue expansion in the HWS was through a combination of hyperplasia and hypertrophy.18,19 Previous research showed that the HWS chickens displayed relative impaired glucose tolerance and hyperglycemia as compared with the LWS,20 and also that the LWS chicks responded to exogenous insulin with hypophagia and hypoglycemia at a lower dose as compared with the HWS.21 Collectively, these studies suggest that LWS and HWS differ in energy metabolism in insulin-dependent tissues, such as skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue, and that differences in feeding behavior could be related to differences in nutrient sensing in the brain.

Metabolic flexibility is the ability of a system to adjust fuel (glucose, fatty acids and amino acids) oxidation on the basis of nutrient availability. Fuel availability is integrated at the cellular level by sensors that activate or inhibit specific metabolic pathways.22 The ability to alter substrate oxidation in response to nutritional state depends on the genetically influenced balance between oxidation and storage capacities.22 Competition between fatty acids and glucose for oxidation occurs at the level of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDHC), which generates acetyl-CoA from pyruvate.23

The PDHC is normally active in most tissues in the fed state,24 and suppressing PDHC activity is crucial to provide three-carbon compounds for glucose synthesis in fasted mammals.25 Conversely, inappropriate suppression of PDHC activity in skeletal muscle might promote the development of hyperglycemia by fueling excessive gluconeogenesis.23 PDHC is rendered inactive by phosphorylation of the α-subunit of its PDH component by PDH kinase (PDK).26 The expression of isoform PDK4 is a major determinant of total PDK activity.27,28 Fasting, diabetes and high-fat diet feeding are all associated with increased expression of PDK4 and total PDK activity in skeletal muscle.25,29 PDK4 expression is regulated by several transcription factors, such as FoxO and PPAR family members.30

In skeletal muscle, forkhead box O1A (FoxO1) regulates the switching from oxidation of carbohydrates to fatty acids31,32 and upregulates PDK4 mRNA during energy deprivation.33 Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ) is a nuclear receptor that regulates the transcription of PDK4.34,35 As a transcriptional coactivator of PPARγ, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator α (PGC1α) can enhance PDK4 expression36 and augment the function of FoxO1 in liver to regulate the transcription of gluconeogenic genes.32

We hypothesized that compared with the LWS, hyperphagia and adiposity in the juvenile HWS chickens are associated with reduced fat oxidation efficiency and metabolic inflexibility and differences in gene expression of metabolic flexibility-associated factors in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle, and relative cellular hypertrophy in white adipose tissue. The objective of this study was to explore the mechanisms underlying differences in energy homeostasis between the juvenile LWS and HWS chickens.

Materials and methods

Animals

All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Virginia Tech. The LWS and HWS chickens were established from a common founder population generated by crosses among seven inbred lines of White Plymouth Rock chickens.1,4 The lines have been maintained as closed populations by continuous selection for high or low body weight at 56 days of age. Description of the breeding and maintenance of the populations is published elsewhere.1,4,37 For the present experiments, feed and water were supplied ad libitum. The diet fed was the same as that which was fed throughout the selection experiment. Animals were fasted for 16 h before sample collection in all experiments and killed by cervical dislocation. Males were used for metabolic and histological assays, whereas both males and females were used for the gene expression assays.

Experiment 1: Fatty acid oxidation and citrate synthase activity assays

At 56 days of age, eight randomly selected chickens from each line were euthanized for collection of pectoralis major, abdominal fat and hypothalamus. At 61 days of age, pectoralis major and gastrocnemius were collected from another 14 randomly selected chickens (seven for each line) for fatty acid oxidation assays. The hypothalamus was dissected visually on the basis of the following anatomical landmarks: anterior cut made at the corticoseptomesencephalic tract, posterior cut at the third cranial nerves, lateral cut 2 mm parallel to the midline on both sides of the brain and finally the dorsal cut from the anterior commissure to 1.0 mm ventral to the posterior commissure.38

The tissue samples were diluted 1:20 (weight:volume) in a buffer containing 0.25 M sucrose, 1 mM EDTA, 0.01 M Tris-Cl and 2 mM ATP, pH 7.4. The sample was minced 200 times, transferred to a 2 ml glass homogenizing tube and homogenized on ice with a Polytron homogenizer and Teflon glass pestle for 30 s at 300 r.p.m. This was repeated in 30 s pulses alternating with 30 s on ice 12 times.

Fatty acid oxidation was assessed by measuring and summing 14CO2 production and 14C-labeled acid-soluble metabolites from the oxidation of [1-14C] palmitic acid (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) as previously described.39 Citrate synthase (CS) activity was measured only in abdominal fat. CS catalyzes the formation of citrate and CoASH from acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate and CoASH reduces 5,5′-dithiobis-2-nitrobenzoic acid (DTNB) levels. CS activity was determined from the reduction of DTNB over time. A volume of 10 ml of 1:5 diluted tissue homogenate was added in duplicate to 170 μl solution containing Tris buffer (0.1 M, pH 8.3), DTNB (1 mM, in 0.1 M Tris buffer) and oxaloacetate (0.01 M, in 0.1 M Tris buffer). Following a 2 min background reading, the spectrophotometer (SPECTRAmax ME, Molecular Devices Corporation, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) was calibrated and 30 μl of 3 mM acetyl-CoA was added to initiate the reaction. Absorbance was measured at 405 nm at 37 °C every 12 s for 7 min. Maximum CS activity was calculated and reported as nmol mg−1 min−1.

Experiment 2: Metabolic flexibility in different skeletal muscle fiber subtypes

For PDH activity and metabolic flexibility assays, randomly selected LWS and HWS chickens (n=7) were killed on day 61 for pectoralis major and gastrocnemius muscle collection as described above. Pyruvate oxidation was assessed by measuring 14CO2 production from the oxidation of [1-14C] pyruvate (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) as previously described.40,41 Metabolic flexibility was assessed by measuring [1-14C] pyruvate oxidation±non-labeled BSA (0.5%)-bound palmitic acid. Flexibility is denoted by the percentage decrease in pyruvate oxidation in the presence of free fatty acid (for example, a higher percentage is indicative of greater metabolic flexibility).

Experiment 3: Adipose tissue histology

At day 65, randomly selected LWS and HWS chickens (n=9) were killed and abdominal fat, clavicular fat (fat above the clavicle) and subcutaneous fat were removed, rinsed in phosphate-buffered saline, fixed in neutral-buffered formalin and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Samples were dehydrated in a graded ethanol series, paraffin embedded, sectioned at 5 μm, mounted and stained with hemotoxylin and eosin. For each tissue, fat was sectioned at three locations, with three sections mounted per slide. Images were captured with a Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope and DS-Ri1 color camera, and images analyzed using NIS-Elements Advanced Research Software (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA). Three images were captured on each section, and the density and area of all adipocytes within the field of an image were measured under 20 × magnification. The threshold method was used to count adipocytes. Adipocytes were treated as binary objects with the restriction that measurements must exceed 100 μm2. The mean area, mean equivalent diameter and mean circularity of each object and the total object numbers as well as the total area were recorded. Object density and the size distribution pattern in each image were also analyzed.

Experiment 4: Real-time PCR assays

Five male and five female chickens randomly selected from LWS and HWS were killed on days 28 and 56. The hypothalamus, liver, pectoralis major, gastrocnemius, abdominal fat, clavicular fat and subcutaneous fat were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Tissues were homogenized using 5 mm stainless steel beads (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA), Isol Lysis reagent (5-Prime, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and a Tissue Lyser II (Qiagen) and total RNA separated following the manufacturer’s instructions (5-Prime). The RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and RNase-free DNase I (Qiagen) were used for total RNA purification. The total RNA samples were evaluated for integrity by agarose-formaldehyde gel electrophoresis and concentration and purity assessed by spectrophotometry at 260/280/230 nm with a Nanophotometer Pearl (IMPLEN, Westlake Village, CA, USA).

First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 200 ng total RNA with a High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). Reactions were performed under the following conditions: 25 °C for 10 min, 37 °C for 120 min and 85 °C for 5 min. Primers for real time PCR were designed with Primer Express 3.0 software (Applied Biosystems) (Supplementary Table 1), and validated for amplification efficiency before use (95–105%). Real-time PCR was performed in duplicate in 10 μl volume reactions that contained 5 μl Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and 3 μl of 10-fold diluted cDNA using a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). PCR was performed under the following conditions: 95 °C for 20 s and 40 cycles of 90 °C for 3 s plus 60 °C for 30 s. A dissociation step consisting of 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, 95 °C for 15 s and 60 °C for 15 s was performed at the end of each PCR reaction to ensure amplicon specificity.

Statistical analysis

Fatty acid oxidation, PDH and CS activity and metabolic flexibility data were analyzed within each tissue, with genetic line (LWS or HWS) as the only effect in the statistical model. Real-time PCR data were analyzed using the ΔΔCT method, where β-actin served as the endogenous control and day 28 HWS liver served as the calibrator sample. Relative quantities calculated as 2−ΔΔCT were used for statistical analysis. Real-time PCR data were analyzed within each tissue, and the statistical model included the main effects of sex (male or female), genetic line, age (28 or 56 days) and the interactions between them. The statistical model for the adipocyte area and diameter data included the effects of fat depot (abdominal or clavicular), genetic line and the interaction between them. Data were analyzed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) using JMP Pro version 10.0 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) and the Fit Model platform. Means were separated using Tukey’s test. Data are presented as least square means±s.e.m. and statistical significance assigned at P<0.05.

Results

Fatty acid oxidation in skeletal muscle, abdominal fat and hypothalamus

Complete oxidation of [1-14C] palmitic acid leads to the formation of 14CO2, whereas an increase in incomplete oxidation of [1-14C] palmitic acid results in a corresponding rise in acylcarnitine production and accumulation, which reflects a state of mitochondrial stress that, in turn, disrupts glucose tolerance. However, higher acid-soluble metabolite (ASM) production is only seen as a detriment when not accompanied by higher CO2 production. Thus we use the ratio of CO2/ASM as a measure of β oxidative efficiency. Disruptions in this ratio may represent mitochondrial overload that is toxic to insulin signaling.

The rate of CO2 production from palmitate oxidation was greater in the 56-day-old LWS chickens than in the HWS chickens for both the abdominal fat (P=0.001) and the hypothalamus (P=0.003, Figure 1a). The rate of ASM production was greater (P=0.003) in the abdominal fat of HWS than the LWS chickens (Figure 1b). Total palmitate oxidation, as a sum of CO2 and ASM production, was greater (P=0.003) in the abdominal fat of HWS chickens as compared with the LWS (Figure 1c). The ratio of CO2/ASM production was greater (P<0.0001) in the abdominal fat of the LWS than the HWS chickens (Figure 1d). There were no differences observed in fatty acid oxidation between the LWS and HWS in the pectoralis major.

Fatty acid oxidation in abdominal fat, pectoralis major and hypothalamus of the 56-day-old male HWS and LWS chickens (n=8). (a) CO2 production, (b) acid soluble metabolite (ASM) production, (c) total palmitate oxidation (CO2 production+ASM production), (d) CO2/ASM ratio. **P<0.01; ***P<0.001. Values represent least squares means±s.e.m.

Fatty acid oxidation and metabolic flexibility in gastrocnemius and Pectoralis major

We next compared the fatty acid oxidation capacity and efficiency of fast-twitch white skeletal muscle (pectoralis major) and slow-twitch red skeletal muscle (gastrocnemius) in the 61-day-old LWS and HWS. The two tissues were considerably different in fatty acid oxidation (Figure 2). Although rates of CO2 (P=0.02, Figure 2a), ASM production (Figure 2b), total palmitate oxidation (Figure 2c) and fatty acid oxidation efficiency (Figure 2d) were all greater in the gastrocnemius of LWS as compared with HWS, the difference was significant only for CO2 production. In the pectoralis major, there were no significant differences in fatty acid oxidation between the lines.

Fatty acid oxidation in the pectoralis major and the gastrocnemius of the 61-day-old male HWS and LWS chickens (n=7). (a) CO2 production, (b) acid soluble metabolite (ASM) production, (c) total palmitate oxidation (CO2 production+ASM production), (d) CO2/ASM ratio. *P<0.05. Values represent least squares means±s.e.m.

While PDH activity did not differ between the 61-day-old HWS and LWS in either of the skeletal muscle tissues, metabolic flexibility (percent change in PDH activity in response to treatment with free fatty acids) was greater (P=0.006) in the pectoralis major of the LWS as compared with the HWS chickens (39.2±7.7 vs 0.3±8.8, respectively). The LWS chickens had much greater (P<0.0001) citrate synthase activity in abdominal fat as compared with the HWS chickens (130±9 vs 60±5 nmol mg−1 min−1, respectively).

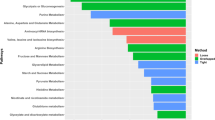

PDK4 mRNA abundance in different tissues

We measured the relative abundance of PDK4 mRNA in the pectoralis major, gastrocnemius, abdominal fat, clavicular fat, subcutaneous fat, hypothalamus and liver at days 28 and 56 (Supplementary Table 2). For brevity, within each tissue, only the highest order significant effects in the statistical model involving genetic line are depicted graphically (Figure 3). There were no significant differences in the liver. The pectoralis major (Figure 3A), gastrocnemius (Figure 3B), abdominal fat (Figure 3C) and subcutaneous fat (Figure 3D) displayed greater (P<0.05) PDK4 mRNA abundance in the HWS than the LWS chickens at 56 days, whereas there were no differences observed between the lines at day 28 in any of these tissues. There was a main effect of line on PDK4 expression in clavicular fat (P=0.02) where mRNA abundance was greater in the LWS than the HWS, irrespective of age. This was the only tissue for which expression was greater in the LWS compared with the HWS. There was an interaction of sex by line (P=0.002) on PDK4 abundance in the hypothalamus, where the HWS females expressed greater quantities of mRNA than the HWS females and the LWS males and females (Figure 3E).

Relative PDK4 mRNA abundance in different tissues of the 28-day and the 56-day-old male and female LWS and HWS chickens (n=10). (A) Two-way interaction of age × genetic line in the pectoralis major, (B) two-way interaction of age × genetic line in the gastrocnemius, (C) two-way interaction of age × genetic line in the abdominal fat, (D) two-way interaction of age × genetic line in the subcutaneous fat, (E) two-way interaction of sex × genetic line in the hypothalamus. Bars with different letters represent significant difference, P<0.05. Values represent least squares means±s.e.m.

FoxO1 expression in different tissues

FoxO1 showed differences in gene expression that were similar to PDK4 (Supplementary Table 2) and similarly, there were no significant differences in the liver. The HWS chickens had greater (P<0.01) levels of FoxO1 mRNA in both pectoralis major and gastrocnemius, irrespective of age. In subcutaneous fat, there was greater (P=0.02) expression of FoxO1 mRNA in HWS at day 56 compared with the LWS, and no difference between the lines at day 28 (Figure 4A). In clavicular fat, there was an age × sex × line interaction on gene expression, where mRNA abundance was greater in LWS males at day 28 than for the other line–sex combinations (Figure 4B). In the hypothalamus, there was a similar pattern causing the interaction, as mRNA was greatest at day 56 in the LWS males than the others (P<0.05, Figure 4C).

Relative FoxO1 mRNA quantities in different tissue of the 28-day-old and the 56-day-old male and female HWS and LWS chickens (n=10). (A) Two-way interaction of age × genetic line in the subcutaneous fat, (B) three-way interaction of age × sex × genetic line in the clavicular fat, and (C) three-way interaction of age × sex × genetic line in the hypothalamus. Bars with different letters represent significant difference, P<0.05. Values represent least squares means±s.e.m.

PPARγ and PGC1α mRNA abundance in different tissues

PPAR γ expression was similar for the genetic lines in the abdominal fat and the hypothalamus (Supplementary Table 2). Expression in liver was greater in the HWS than in the LWS (P=0.002). For both pectoralis major (Figure 5A) and gastrocnemius (Figure 5B), there was an interaction of age × line where expression was greater (P<0.05) in LWS than HWS at day 28, with no differences between the lines at day 56. In pectoralis major, there was a line × sex interaction on PPAR γ expression, where mRNA abundance was greater (P<0.05) in the LWS females than the HWS females (Figure 5C). There was a main effect of line on PPAR γ mRNA in both the clavicular fat and the subcutaneous fat, with greater (P<0.05) expression in the LWS as compared with the HWS chickens.

PPARγ and PGC1α expression in different tissues of the 28-day-old and the 56-day-old male and female HWS and LWS chickens (n=10). (A) Age × line interaction on PPAR γ mRNA in the pectoralis major, (B) age × line interaction on PPAR γ mRNA in the gastrocnemius, (C) sex × line interaction on PPAR γ mRNA in the pectoralis major, (D) interaction of genetic line × sex on PGC1 α mRNA levels in the gastrocnemius. Bars with different letters represent significant differences, P<0.05. Values represent least squares means±s.e.m.

For PGC1 α, the only significant difference between lines was in gastrocnemius, with an interaction of line × sex on mRNA (P=0.02; Supplementary Table 2). In the gastrocnemius, the HWS males expressed more PGC1 α than the LWS males and the HWS females (Figure 5D).

Adipocyte cellularity

Adipocyte areas were greater in the HWS than in the LWS for abdominal (P<0.0001) and clavicular fat (P<0.0001; Figure 6A). In the HWS, adipocytes were largest in clavicular fat, smallest in subcutaneous fat and intermediate in the abdominal fat (P<0.01). The mean diameters of fat cells showed similar differences, being greater in the HWS abdominal (P<0.0001) and clavicular fat (P<0.0001; Figure 6B). The patterns were similar for adipocyte diameter between fat depots in HWS, with largest cells in the clavicular fat and smallest in the subcutaneous fat (Figure 6B). Overall cellular density was greater (P<0.0001) in the LWS than in the HWS in both abdominal fat and clavicular fat (Figure 6C). In the HWS, there were more adipocytes per unit area in the subcutaneous fat than the clavicular fat (P<0.01). There was not enough subcutaneous fat to sample from the LWS, thus subcutaneous fat data are reported only for the HWS chickens.

Adipocyte cellularity in different adipose tissue depots of the 65-day-old male HWS and LWS chickens (n=9). (A) Mean area (μm2) of adipocytes in abdominal fat, clavicular fat and subcutaneous fat in the two genetic lines, (B) mean equivalent diameter (μm) of adipocytes in abdominal fat, clavicular fat and subcutaneous fat in the two genetic lines, (C) adipocytes density (per μm2) in abdominal fat, clavicular fat and subcutaneous fat in the two genetic lines, (D) adipocyte size distribution in different adipose tissues in the two genetic lines. Bars with different letters represent significant differences, P<0.05. In the bar graphs, values represent least squares means±s.e.m. Values in D represent mean numbers of adipocytes of a certain area (μm2).

General size distribution of adipocytes among fat tissues within the same line followed a similar pattern (Figure 6D). Most of the adipocytes in the HWS fat samples were between 1000 and 4000 μm2, with adipocytes as large as 9500 μm.2 The LWS, on the other hand, contained greater numbers of small cells, with most adipocytes between 500 and 2000 μm,2 and no adipocytes larger than 5200 μm2 (Figure 6D).

Discussion

Fatty acid oxidation and metabolic flexibility

Alterations in fatty acid oxidation in the hypothalamus could be associated with appetite dysregulation,42 and long-chain fatty acids serve as signals in modulating energy balance.43,44 In the hypothalamus, we observed greater rates of CO2 production from palmitate oxidation in the LWS chickens, indicative of greater total oxidation and perhaps a difference in energy sensing status.

In chickens, the pectoralis major is composed exclusively of type II, fast-twitch, white muscle fibers, whereas the gastrocnemius is composed mainly of type I, slow-twitch red muscle fiber subtypes.45 The LWS chickens showed greater fatty acid oxidation efficiency in abdominal fat and red muscle. In white muscle, there was no significant difference. This suggests that red muscle, which contains more mitochondria as compared with white muscle, is a site of enhanced fatty acid oxidation in the LWS chickens.

It was suggested that the high rate of lipolysis in abdominal fat prevented net fat accumulation in the 28-day-old LWS chickens, although the mechanism underlying the differences in metabolism were unknown.17 Those data combined with the present results suggest a greater availability of fatty acids for oxidation that are accompanied by greater rates of oxidation and oxidative efficiency in the LWS chickens.

As a pace-making enzyme in the first step of the TCA Cycle, CS can regulate entry of acetyl-CoA into the TCA cycle. It is also a widely used quantitative marker for mitochondrial content.46 In the 56-day-old LWS chickens, there was more than twofold greater CS activity, and threefold greater adipocyte density in LWS than HWS abdominal fat. These results are consistent with the fatty acid oxidation data, suggesting that the abdominal fat of LWS are more densely populated by mitochondria, and associated with greater rates of CO2 production. This corresponded to reduced rates of ASM production, indicating that the output of the TCA cycle is more closely matched to the rates of fatty acid oxidation, associated with enhanced oxidative efficiency in the LWS. The LWS chickens also showed much greater metabolic flexibility (down-regulating pyruvate dehydrogenase to accommodate the influx of acetyl-CoA from fatty acid oxidation) in response to treatment with palmitate in both adipose tissue and skeletal muscle.

Gene expression in different tissues

No major differences in gene expression were noted in the 28-day-old chickens, although metabolic assays were not performed at this age. Changes between 28 and 56 days of age could be due to the alterations in growth and body composition that occur during those four weeks.

Down-regulation of PDK4 and FoxO1 and increased expression of PPARγ could inhibit PDHC phosphorylation in both white and red muscle subtypes.28,45 As endogenous PPAR ligands, free fatty acids and their derivatives have been implicated to be responsible for enhanced PDK expression in fasting and diabetes.47 This was consistent with the greater fatty acid oxidation efficiency and relatively higher PPARγ mRNA expression in the LWS fat tissues and skeletal muscle. In the abdominal fat, there was strikingly higher fatty acid oxidation efficiency in the LWS, and this was also associated with greater activity of citrate synthase and less expression of PDK4, consistent with greater flux through the β-oxidation pathway. Total palmitate oxidation was greater in the HWS abdominal fat, consistent with the HWS being obese and having an overall greater capacity for energy oxidation. Although metabolic activities were not measured in clavicular or subcutaneous fat, both depots showed different patterns of gene expression, where PDK4 mRNA was greater in the LWS and HWS, respectively, whereas for PPAR γ, expression was greater in the LWS in both fat depots. Yet for all tissues where FoxO1 expression was greater in the HWS (subcutaneous fat and both skeletal muscle tissues), there was also greater expression of PDK4 in the HWS, suggestive of coordinate regulation. Although metabolic and histological assays were performed only on males, the gene expression differences for PPAR γ and PGC1 α in males and females suggest that there could be effects of body composition in juveniles on metabolism that are influenced by gender.

Adipocyte cellularity

The adipocytes in all three adipose tissues of HWS chickens were larger and sparser as compared with the LWS adipocytes. There were also ‘oversized’ adipocytes in the abdominal fat and clavicular fat in the HWS chickens, which are described as being markers for inflammation and insulin resistance in mammals.48 These results are consistent with those reported for the 280-day-old chickens from the 29th generation of selection,18 where the LWS had a greater number of small, unfilled adipocytes whereas the HWS had a fewer number of unfilled cells in the abdominal fat. In response to force-feeding, the LWS chickens accommodated the increased energy through expansion of pre-existing adipocytes whereas the HWS generated new cells to accommodate the lipids. It is intriguing that in our study with juveniles, the HWS had already reached the point where the abdominal fat contained primarily filled adipocytes, with very few unfilled cells. The average size of the fat cell was similar between all depots within the lines, which was unexpected given the differences in gene expression and differences in metabolism reported for visceral vs subcutaneous fat in mammals.

In conclusion, the underlying mechanisms in the complex network that regulates energy homeostasis are critical to understand in the research of obesity and metabolic syndrome. Results from our study suggest that in the relatively hypophagic and lean chickens, an enhanced ability to utilize fatty acids for energy and efficiently oxidize excess energy, prevents the accumulation of white adipose tissue, and greater fatty acid oxidation in the hypothalamus may indicate that the fuel sensing status in the LWS is disrupted such that satiety-inducing signals predominate in appetite control. Greater metabolic flexibility in the skeletal muscle of the LWS is also consistent with superior oxidative efficiency and capacity to oxidize lipids. Differences in metabolism were also associated with differences in gene expression in adipose tissue and skeletal muscle of several genes that encode factors involved in PDHC regulation that have an essential role in glucose and lipid metabolism. Information from this study may be useful in elucidating the molecular mechanisms underlying obesity and metabolic disorders.

References

Dunnington EA, Siegel PB . Long-term divergent selection for eight-week body weight in white Plymouth rock chickens. Poult Sci 1996; 75:1168–1179.

Zelenka DJ, Dunnington EA, Cherry JA, Siegel PB . Anorexia and sexual maturity in female white rock chickens. I. Increasing the feed intake. Behav Genet 1988; 18: 383–387.

Dunnington EA, Siegel PB, Cherry JA, Jones DE, Zelenka DJ . Physiological traits in adult female chickens after selection and relaxation of selection for 8-week body weight. J Anim Breedg Genet 1986; 103: 51–58.

Dunnington EA, Honaker CF, McGilliard ML, Siegel PB . Phenotypic responses of chickens to long-term, bidirectional selection for juvenile body weight—historical perspective. Poult Sci 2013; 92: 1724–1734.

Katanbaf MN, Dunnington EA, Siegel PB . Allomorphic relationships from hatching to 56 days in parental lines and F1 crosses of chickens selected 27 generations for high or low body weight. Growth Dev Aging 1988; 52: 11–21.

Burgener JA, Cherry JA, Siegel PB . The association between sartorial fat and fat deposition in meat-type chickens. Poultry Sci 1981; 60: 54–62.

Zhang W, Sumners LH, Siegel PB, Cline MA, Gilbert ER . Quantity of glucose transporter and appetite-associated factor mRNA in various tissues after insulin injection in chickens selected for low or high body weight. Physiol Genomics 2013; 45: 1084–1094.

Kuo AY, Cline MA, Werner E, Siegel PB, Denbow DM . Leptin effects on food and water intake in lines of chickens selected for high or low body weight. Physiol Behav 2005; 84: 459–464.

Newmyer BA, Siegel PB, Cline MA . Neuropeptide AF differentially affects anorexia in lines of chickens selected for high or low body weight. J Neuroendocrinol 2010; 22: 593–598.

Smith ML, Prall BC, Siegel PB, Cline MA . The threshold of insulin-induced hypophagia is lower in chicks selected for low rather than high juvenile body weight. Behav Brain Res 2011; 216: 719–722.

Cline MA, Kuo AY, Smith ML, Nandar W, Prall BC, Siegel PB et al. Differential feed intake responses to central corticotrophin releasing factor in lines of chickens divergently selected for low or high body weight. Comp Biochem Physiol Part A Mol Integr Physiol 2009; 152: 130–134.

Cline MA, Nandar W, Bowden C, Calchary W, Smith ML, Prall B et al. The threshold of amylin-induced anorexia is lower in chicks selected for low compared to high juvenile body weight. Behav Brain Res 2010; 208: 650–654.

Cline MA, Nandar W, Bowden C, Hein PP, Denbow DM, Siegel PB . Differential feeding responses to central alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone in genetically low and high body weight selected lines of chickens. Life Sci 2008; 83: 208–213.

Cline MA, Prall BC, Smith ML, Calchary WA, Siegel PB . Differential appetite-related responses to central neuropeptide S in lines of chickens divergently selected for low or high body weight. J Neuroendocrinol 2008; 20: 904–908.

Cline MA, Siders R, Newmyer BA, Smith ML, Siegel PB . Both calcitonin and calcitonin gene-related peptides' thresholds of hypophagia are considerably lower in chicks selected for high rather than low juvenile body weight. Physiol Behav 2010; 101: 254–259.

Newmyer BA, Nandar W, Webster RI, Gilbert E, Siegel PB, Cline MA . Neuropeptide Y is associated with changes in appetite-associated hypothalamic nuclei but not food intake in a hypophagic avian model. Behav Brain Res 2013; 236: 327–331.

Calabotta DF, Cherry JA, Siegel PB, Jones DE . Lipogenesis and lipolysis in fed and fasted chicks from high and low body weight lines. Poult Sci 1985; 64: 700–704.

Robey WW, Van Krey HP, Cherry JA, Siegel PB, Bliss BA . Adipocyte dynamics in the retroperitioneal fat depot of genetically selected adult high- and low-weight line chickens. Arch. Gerflugelk 1992; 56: 68–72.

Robey WW, Cherry JA, Siegel PB, Van Krey HP . Hyperplastic response of adipose tissue to caloric overconsumption in sexually mature chickens. Poult Sci 1988; 67: 800–808.

Sinsigalli NA, McMurtry JP, Cherry JA, Siegel PB . Glucose tolerance, plasma insulin and immunoreactive glucagon in chickens selected for high and low body weight. J Nutr 1987; 117: 941–947.

Smith ML, Prall BC, Siegel PB, Cline MA . The threshold of insulin-induced hypophagia is lower in chicks selected for low rather than high juvenile body weight. Behav Brain Res 2011; 216: 719–722.

Galgani JE, Moro C, Ravussin E . Metabolic flexibility and insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2008; 295: E1009–E1017.

Sugden MC . PDK4: a factor in fatness? Obes Res 2003; 11: 167–169.

Sugden MC, Holness MJ . Interactive regulation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and the carnitine palmitoyltransferase system. FASEB J 1994; 8: 54–61.

Holness MJ, Kraus A, Harris RA, Sugden MC . Targeted upregulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK)-4 in slow-twitch skeletal muscle underlies the stable modification of the regulatory characteristics of PDK induced by high-fat feeding. Diabetes 2000; 49: 775–781.

Kwon HS, Harris RA . Mechanisms responsible for regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 gene expression. Adv Enzyme Regul 2004; 44: 109–121.

Gudi R, Bowker-Kinley MM, Kedishvili NY, Zhao Y, Popov KM . Diversity of the pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase gene family in humans. J Biol Chem 1995; 270: 28989–28994.

Strumilo S . Short-term regulation of the mammalian pyruvate dehydrogenase complex. Acta Biochim Pol 2005; 52: 759–764.

Wu P, Inskeep K, Bowker-Kinley MM, Popov KM, Harris RA . Mechanism responsible for inactivation of skeletal muscle pyruvate dehydrogenase complex in starvation and diabetes. Diabetes 1999; 48: 1593–1599.

Constantin-Teodosiu D, Constantin D, Stephens F, Laithwaite D, Greenhaff PL . The role of FOXO and PPAR transcription factors in diet-mediated inhibition of PDC activation and carbohydrate oxidation during exercise in humans and the role of pharmacological activation of PDC in overriding these changes. Diabetes 2012; 61: 1017–1024.

Guarente L, Kenyon C . Genetic pathways that regulate ageing in model organisms. Nature 2000; 408: 255–262.

Gross DN, van den Heuvel AP, Birnbaum MJ . The role of FoxO in the regulation of metabolism. Oncogene 2008; 27: 2320–2336.

Furuyama T, Kitayama K, Yamashita H, Mori N . Forkhead transcription factor FOXO1 (FKHR)-dependent induction of PDK4 gene expression in skeletal muscle during energy deprivation. Biochem J 2003; 375: 365–371.

Sears DD, Hsiao A, Ofrecio JM, Chapman J, He W, Olefsky JM . Selective modulation of promoter recruitment and transcriptional activity of PPARgamma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 2007; 364: 515–521.

Wan Z, Thrush AB, Legare M, Frier BC, Sutherland LN, Williams DB et al. Epinephrine-mediated regulation of PDK4 mRNA in rat adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2010; 299: C1162–C1170.

Attia RR, Connnaughton S, Boone LR, Wang F, Elam MB, Ness GC et al. Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 4 (PDK4) by thyroid hormone: role of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator (PGC-1 alpha). J Biol Chem 2010; 285: 2375–2385.

Marquez GC, Speidel SE, Enns RM, Garrick DJ . Genetic diversity and population structure of American Red Angus cattle. J Anim Sci 2010; 88: 59–68.

Puelles L . The Chick Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates: An Atlas Featuring Neuromeric Subdivisions and Mammalian Homologies. 1st edn.Academic Press: Amsterdam; Boston, 2007.

Frisard MI, McMillan RP, Marchand J, Wahlberg KA, Wu Y, Voelker KA et al. Toll-like receptor 4 modulates skeletal muscle substrate metabolism. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2010; 298: E988–E998.

Power RA, Hulver MW, Zhang JY, Dubois J, Marchand RM, Ilkayeva O et al. Carnitine revisited: potential use as adjunctive treatment in diabetes. Diabetologia 2007; 50: 824–832.

Anderson AS, Roberts PC, Frisard MI, McMillan RP, Brown TJ, Lawless MH et al. Metabolic changes during ovarian cancer progression as targets for sphingosine treatment. Exp Cell Res 2013; 319: 1431–1442.

Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Jaswal JS . Targeting intermediary metabolism in the hypothalamus as a mechanism to regulate appetite. Pharmacol Rev 2010; 62: 237–264.

Lopez M, Vidal-Puig A . Brain lipogenesis and regulation of energy metabolism. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2008; 11: 483–490.

Serra D, Mera P, Malandrino MI, Mir JF, Herrero L . Mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation in obesity. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013; 19: 269–284.

Ashmore CR, Doerr L . Postnatal development of fiber types in normal and dystrophic skeletal muscle of the chick. Exp Neurol 1971; 30: 431–446.

Larsen S, Nielsen J, Hansen CN, Nielsen LB, Wibrand F, Stride N et al. Biomarkers of mitochondrial content in skeletal muscle of healthy young human subjects. J Physiol 2012; 590: 3349–3360.

Jeong JY, Jeoung NH, Park KG, Lee IK . Transcriptional regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase. Diabetes Metab J 2012; 36: 328–335.

Maffeis C, Silvagni D, Bonadonna R, Grezzani A, Banzato C, Tato L . Fat cell size, insulin sensitivity, and inflammation in obese children. J Pediatr 2007; 151: 647–652.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the Paul B Siegel Poultry Center Farm Manager, Mike Graham, for his outstanding support in the chicken trials.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on International Journal of Obesity website

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, S., McMillan, R., Hulver, M. et al. Chickens from lines selected for high and low body weight show differences in fatty acid oxidation efficiency and metabolic flexibility in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue. Int J Obes 38, 1374–1382 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2014.8

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Transcriptional profiling and pathway analysis reveal differences in pituitary gland function, morphology, and vascularization in chickens genetically selected for high or low body weight

BMC Genomics (2019)

-

Fasting differentially alters the hypothalamic proteome of chickens from lines with the propensity to be anorexic or obese

Nutrition & Diabetes (2019)

-

The effects of dietary macronutrient composition on lipid metabolism-associated factor gene expression in the adipose tissue of chickens are influenced by fasting and refeeding

BMC Obesity (2017)

-

Transcriptional analysis of abdominal fat in chickens divergently selected on bodyweight at two ages reveals novel mechanisms controlling adiposity: validating visceral adipose tissue as a dynamic endocrine and metabolic organ

BMC Genomics (2017)

-

Hypothalamic differences in expression of genes involved in monoamine synthesis and signaling pathways after insulin injection in chickens from lines selected for high and low body weight

neurogenetics (2015)