Abstract

Objective:

Maternal overweight/obesity and depression are among the most prevalent pregnancy complications, and although individually they are associated with poor pregnancy outcomes, their combined effects are unknown. Owing to this, the objective of this study was to determine the prevalences and the individual and combined effects of depression and overweight/obesity on neonatal outcomes.

Methods:

A retrospective cohort study of all singleton hospital births at >20 weeks gestation in Ontario, Canada (April 2007 to March 2010) was conducted. The primary outcome measure was a composite neonatal outcome, which included: stillbirth, neonatal death, preterm birth, birth weight <2500 g, <5% or >95%, admission to a neonatal special care unit, or a 5-min Apgar score <7.

Results:

Among the 70 605 included women, 49.7% had a healthy pre-pregnancy BMI, whereas 50.3% were overweight/obese; depression was reported in 5.0% and 6.2%, respectively. Individually, depression and excess pre-pregnancy weight were associated with an increased risk of adverse neonatal outcomes, but the highest risk was seen when they were both present (16% of non-depressed healthy weight pregnant women, 19% of depressed healthy weight women, 20% of non-depressed overweight/obese women and 24% of depressed overweight/obese women). These higher risks of adverse neonatal outcomes persisted after accounting for potential confounding variables, such as maternal age, education and pre-existing health problems (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.22, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.13–1.33, adjusted OR 1.23, 95% CI 1.18–1.28 and adjusted OR 1.42, 95% CI 1.31–1.54, in the last three groups above, respectively, relative to non-depressed healthy weight women). There was no significant interaction between weight category and depression (P=0.2956).

Conclusions:

When dually present, maternal overweight/obesity and depression combined have the greatest impact on the risk of adverse neonatal outcomes. Our findings have important public health implications given the exorbitant proportions of both of these risk factors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Two pregnancy complications have become excessively prevalent: maternal excess weight and depression. The continuum of overweight and obesity is now the most common complication of pregnancy. In the United Kingdom, 33%1 to 41%2 of pregnant women are overweight or obese, as are 45% of those in Northern Ireland,3 while in the United States, regional variation ranges from 12%4 to 38%5 of pregnant women being overweight and 11%6 to 40%5 obese. Depression affects 5–15% of women during pregnancy according to a recent systematic review.7 A recent systematic review highlighted the co-prevalence of obesity and depression during pregnancy, but did not examine outcomes of the pregnancies.8

Maternal overweight/obesity and depression are individually associated with a number of similar adverse neonatal outcomes, but previous studies have typically not accounted for the presence of both. Women with a high body mass index (BMI) are at increased risk of very preterm birth, with the risk increasing according to pre-pregnancy BMI, such that overweight, obese and very obese women have a 16%, 45% and 82% increased risk, respectively, relative to healthy weight women, as reported in a meta-analysis of 84 studies.9 Similarly, depressed women have higher risks of preterm birth10 and their infants have lower Apgar scores.11 Other adverse neonatal outcomes, such as low Apgar scores12, 13 and admission to a neonatal intensive care unit,12, 14 are also increased in obese women.

Despite the intuitive conclusion that many pregnant women likely experience both overweight/obesity and depression, and that the combined exposure may be associated with an even greater risk of poor pregnancy outcomes than the risk of the individual exposures, there has been limited information on their dual effects. We aimed to determine the combined prevalences of overweight/obesity and depression and their individual and combined associations with adverse infant outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study design

We performed a retrospective cohort study according to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guideline.15 We identified all births in all Ontario hospitals between 1 April 2007 and 31 March 2010.

Data source

We used a population-based database that captures information on all hospital births in the province of Ontario, Canada, the most populous province in the country16 (the Better Outcomes Registry and Network, BORN).17 Data quality is maintained by formal training of new users, and logic-checking mechanisms that are built into the system to minimize missing or erroneous data. A recent quality audit of BORN data found that the percent agreement with chart data for our included variables was typically in the mid-high 90s, with minor exceptions.18 As neither psychiatric illness nor BMI were included in that audit, we audited 2009 data and found a kappa of 0.73 for psychiatric illness and a correlation of 0.99 for pre-pregnancy BMI, comparing physician records with BORN data (unpublished data). Antepartum information is entered in pre-birth registration clinics and on labour floors before birth, whereas postpartum information, such as feeding at discharge, is entered by nurses on the postpartum floors before maternal/infant discharge.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

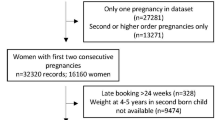

We included all hospital births of singletons delivered at >20 weeks gestation. Planned home births, which constitute a small proportion of all births in Ontario, are not included in BORN and were not part of this study. We excluded: twins and higher order multiples as they have higher risks of adverse perinatal outcomes, infants of women who had given birth previously in the same hospital during the study period for the sake of statistical independence, infants born to women who were underweight at the start of pregnancy as they did not fit our research question and infants born to women lacking information on depression or weight status (Figure 1).

Exposure and outcomes

The first main exposure, overweight/obesity, was defined as a pre-pregnancy BMI 25.0–29.9 kg m–2 (overweight) or BMI ⩾30.0 kg m–2 (obesity). The reference group was healthy weight, defined as pre-pregnancy BMI 18.5–24.9 kg m–2. Both height and pre-pregnancy weight were also typically obtained from patient self-report as recorded in the medical charts. BMI was either provided in the database or was calculated based on the pre-pregnancy weight and height.

The other main exposure, depression, was defined according to patient self-report as either depression during the current pregnancy or a previous history of depression. Thus, ‘depression’ was not based on a clinical diagnosis using the criteria from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV (DSM-IV), but instead it was based on the results of screening that occurs as standard practise during pregnancy. For secondary analyses, we examined depression during the current pregnancy only.

The primary outcome was a composite of adverse neonatal outcomes, which included: stillbirth, neonatal death, preterm birth <37 weeks, low birth weight <2500 g, small for gestational age <5% for gestation and sex, large for gestational age >95% for gestation and sex, admission to a neonatal intensive care unit or special nursery or Apgar score <7 at 5 minutes. A composite outcome was chosen because the association between pregnancy complications and the overall health of the infant is the most clinically relevant question (that is, the clinician is primarily concerned with delivering a healthy baby and is not necessarily focused on any one aspect of the infant’s health). The individual conditions that were included in the composite outcome were selected because they are deemed to be associated with the greatest morbidity and are common neonatal outcomes.

The main secondary outcomes were the individual components included in the composite outcome, as well as small for gestational age <3 and <10%, large for gestational age >90 and >97%, macrosomia >4500 g, neonatal resuscitation, phototherapy, shoulder dystocia, infant feeding at discharge, Apgar score at 1 and at 5 min, gestational age, arterial cord pH, arterial base excess, venous cord pH and venous base excess.

Potential confounding variables

There were a number of potential confounding variables that were controlled for in our analyses, which may be associated with maternal weight and/or depression, as well as one or more of the adverse neonatal outcomes comprising the primary composite outcome. The following continuous variables were included: maternal age (as the midpoint of the corresponding 5-year interval), parity, the number of previous term births and the number of previous preterm births. Although individual participants’ education level, income and employment status were not available, we did have information on the proportion of individuals with education greater than high school in the participants’ neighbourhood, the median neighbourhood income (entered in $20 000 increments in the regression model) and the median proportions employed and in the labour force in their neighbourhood. These data were defined according to Statistics Canada census data19 based on the postal code. The following binary variables were included: education (having more than a high school education), speaking English at home (self-reported by the participant, which meant to serve as a proxy for race/ethnicity, because we did not have other variables on race/ethnicity, but felt it was an important potential confounding variable), previous caesarean, smoking during pregnancy, any drug/alcohol/medication use during pregnancy, physical health problems, other mental health problems (besides depression, specifically anxiety during this pregnancy, previous history of anxiety or other mental illness), pregestational diabetes, use of in vitro fertilization technology, having a first trimester prenatal visit, attending prenatal classes and infant sex. Type of antenatal care provider was also included as a potential confounding variable (categorical variable coded as exclusive care by: midwife, family physician, nurse practitioner or obstetrician, or no exclusive care provider). Preeclampsia, gestational diabetes and other antepartum complications may be part of the causal pathway from maternal overweight/obesity to poor neonatal outcomes, and were thus not adjusted for in our analyses.

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics were compared between four groups of women: women without depression and with a healthy pre-pregnancy BMI, women with depression and with a healthy BMI, women without depression who were overweight/obese and women with depression who were overweight/obese. Continuous data were compared using an analysis of variance, and proportions were compared using a χ2 test, with a two-tailed P-value. The associations between each exposure variable (depression and/or pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity as binary variables) and the outcome were examined using univariate logistic regression, followed by multivariable logistic regression, which also adjusted for the a priori selected potential confounding variables listed above. Point estimates were reported as odds ratios (OR) with accompanying 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

A priori, we performed a power calculation. Assuming an overall event rate of 10% and a doubling in risk among depressed women, we would expect to see poor outcomes in 9.5% of non-depressed women, and would have over 99% power to detect this. Similarly, assuming an overall event rate of 10% and a doubling in risk among overweight/obese women, we would expect to see poor outcomes in 6.25% of healthy weight women, and would have over 99% power to detect the doubling in risk, with a two-tailed alpha of 5%. Assuming that poor neonatal outcomes will occur 10% of the time, and that the relative risk (RR) of a poor outcome is doubled in the depressed healthy weight women compared with their non-depressed healthy weight counterparts, and that the risk is also doubled in overweight non-depressed women as compared with their healthy weight non-depressed counterparts, if the risk of a poor outcome is 6.1% in the non-depressed healthy weight group, we would have 84% power to detect an interaction effect between depression and excess weight.

Missing predictor variables were imputed using multiple imputation.20, 21 Analyses were performed using SAS-PC statistical software (version 9.2; SAS institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The study was approved by the Faculty of Health Sciences/McMaster University Research Ethics Board.

Results

There were 416 971 hospital births between 1 April 2007 and 31 March 2010 in Ontario, Canada (Figure 1). From these, we excluded infants who did not meet our inclusion criteria, yielding 70 605 infants who were included in our analyses.

Descriptive analyses

More than half of women in the study were overweight or obese according to their pre-pregnancy BMI (50.3%); 5.0% of women of healthy weight reported being depressed during the current pregnancy or having a history of depression, compared with 6.2% of overweight/obese women. Other baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1, with key characteristics highlighted here. On average, women who were depressed were slightly younger than their non-depressed similar weight counterparts (29.2 years—depressed healthy weight women versus 30.4 years—non-depressed healthy weight women, and 29.4 years—depressed overweight/obese women versus 30.4 years—non-depressed overweight/obese women, P<0.001). Depressed women lived in neighbourhoods that had a lower median family income compared with non-depressed women, as did women who were overweight/obese compared with those who were of healthy weight ($77 561—non-depressed healthy weight women, $71 569—depressed healthy weight women, $73 969—non-depressed overweight/obese women and $69 620—depressed overweight/obese women, P<0.001).

Depressed women had a higher prevalence of smoking during the pregnancy (28% of healthy weight women and 28% of overweight/obese women) compared with non-depressed women (9.2% of healthy weight women and 12% of overweight/obese, P<0.001). Similarly, a significantly greater proportion of depressed women reported any illicit drug, alcohol or prescription medication use during pregnancy (12% of healthy weight women and 16% of overweight/obese women), about 10 times the proportion of non-depressed women (1.5% of healthy weight women and 1.7% of overweight/obese women, P<0.001).

Women who did not have BMI information recorded (N=37 468) and were thus excluded from our analyses were on average 29.8 years of age (s.d. 5.7), lived in neighbourhoods with a median family income of $70 169, and 45.0% of them were nulliparous. Women who were excluded because they did not have depression status recorded (N=2958) were on average 28.4 years of age (s.d. 5.3), lived in neighbourhoods with a median family income of $66 908 and 44.6% of them were nulliparous.

Univariate analysis

The adverse neonatal composite outcome occurred in 16% of non-depressed healthy weight pregnant women, 19% of depressed healthy weight women, 20% of non-depressed overweight/obese women and 24% of depressed overweight/obese women (Table 2). The results were almost identical between the primary analysis (depression defined as occurring during the current pregnancy or a previous history of depression) and the secondary analysis (depression defined as occurring only during the current pregnancy).

Depressed women and overweight/obese women experienced preterm birth more often than their reference groups, with the highest prevalence in women who were depressed and overweight/obese (6.0% of non-depressed healthy weight women versus 7.2% of depressed healthy weight women, and 6.6% of non-depressed overweight/obese women versus 8.2% of depressed overweight/obese women, P<0.001; Table 3). Although higher prevalences of low birth weight <2500 g would be expected in groups experiencing a higher prevalence of preterm birth, this did not hold among overweight/obese women, in whom the depressed group had a lower prevalence (3.9% versus 4.4% in the non-depressed group). Besides the absolute cut off of <2500 g, small infant size is also commonly reported after taking into account gestational age and sex, using percentiles. Small for gestational age, whether defined as <10, <5 or <3%, was more common among non-depressed women than their similar weight depressed counterparts (P<0.001 for all three outcomes). The prevalence of macrosomia (>4500 g) was the highest among the depressed overweight/obese women (1.1% in non-depressed healthy weight women, 1.7% in depressed healthy weight women, 2.8% in non-depressed overweight/obese women and 3.3% in depressed overweight/obese women, P<0.001), as was large for gestational age, whether defined as >90, >95 or >97%, (P<0.001 for all three outcomes).

Admission to the neonatal intensive care unit was higher among infants born to depressed women and overweight/obese women, with the highest prevalence among women with both conditions (5.5% of non-depressed healthy weight women versus 6.4% of depressed healthy weight women, and 6.2% of non-depressed overweight/obese women versus 7.0% of depressed overweight/obese women, P=0.001), as was newborn resuscitation and shoulder dystocia.

Multivariable logistic regression

The higher risk of the adverse neonatal composite outcome persisted after accounting for other factors (adjusted OR 1.22, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.33 in depressed healthy weight women; OR 1.23, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.28 in non-depressed overweight/obese women; and OR 1.42, 95% CI: 1.31, 1.54 in depressed overweight/obese women, all relative to non-depressed healthy weight women) (Table 4). We had hypothesized that there would be a significant interaction between depression and weight category (BMI ⩾25 kg m–2), however, there was not, (P=0.29).

In the secondary analysis, relative to non-depressed women of healthy weight, the adjusted OR for the adverse neonatal composite outcome in healthy weight women who reported being depressed during the current pregnancy was 1.34 (95% CI: 1.11, 1.62), OR 1.23 (95% CI: 1.18, 1.28) in non-depressed overweight/obese women and OR 1.36 (95% CI: 1.22, 1.53) in depressed overweight/obese women (Table 4).

For our secondary outcomes, we found that compared with non-depressed women of healthy weight, the adjusted OR of preterm birth <37 weeks was 1.22 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.42) in depressed healthy weight women, OR 1.01 (95% CI: 0.94, 1.07) in non-depressed overweight/obese women and OR 1.19 (95% CI: 1.05, 1.34) in depressed overweight/obese women, whereas the adjusted OR of macrosomia >90% was 1.24 (95% CI: 1.08, 1.42), OR 1.82 (95% CI: 1.73, 1.92) and OR 2.08 (95% CI: 1.88, 2.30), respectively.

The adverse neonatal outcomes persisted when the analyses (post hoc) were restricted to infants born at term, with adjusted OR 1.22 (95% CI: 1.11, 1.34) in depressed healthy weight women, OR 1.33 (95% CI: 1.27, 1.40) in non-depressed overweight/obese women and OR 1.52 (95% CI: 1.37, 1.68) in depressed overweight/obese women, respectively.

As a sensitivity analysis, we compared results with and without multiple imputation and found no important differences (data not shown).

Discussion

In this large, retrospective cohort study, we found that individually, depression and excess pre-pregnancy weight were each associated with an increased risk of adverse neonatal outcomes, but the highest risk was seen when they were both present. These higher risks of adverse neonatal outcomes persisted after accounting for potential confounders (adjusted OR 1.22, 95% CI: 1.13, 1.33 in depressed healthy weight women; OR 1.23, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.28 in non-depressed overweight/obese women; and OR 1.42, 95% CI: 1.31, 1.54, in depressed overweight/obese women, relative to non-depressed healthy weight women). Although for infants the increases in the risks are modest in magnitude, the high prevalences of overweight/obesity and depression signify that these risks are important on the population level, and are thus a serious public health concern.

Contextualizing our findings in relation to previous literature is challenging, as studies typically fail to account for depression when examining weight, and vice versa. A previous meta-analysis demonstrated that overweight/obese women have an increased risk of preterm birth <33 weeks (pooled RR 1.26, 95% CI: 1.14, 1.39), a decreased risk of growth restriction in their infants (pooled RR 0.79, 95% CI: 0.73, 0.86) and no significant effect on the risk of having a low birth weight infant (pooled RR 0.90, 95% CI: 0.79, 1.01 in developed countries).9 Similarly, a previous meta-analysis demonstrated that depression is associated with preterm birth (pooled adjusted RR 1.24, 95% CI: 1.04, 1.47), although growth restriction was not significantly affected (adjusted RR 1.17, 95% CI: 0.82, 1.64).10 The risk of low birth weight was also increased for depressed women, although this increase in risk was smaller in developed countries relative to developing ones (RR 1.10, 95% CI: 1.01, 1.21 in the United States).10

Biologic basis for the increase in adverse infant outcomes that we found have been hypothesized to include, in the case of obesity, hyperlipidaemia, which may be associated with thrombosis and decreased perfusion of the placenta,22 high levels of C-reactive protein23 and other inflammatory cytokines,24 and overall enhanced protease activity, which may degrade fetal membranes, predisposing the mother to premature rupture of membranes and preterm birth.25 Depression is characterized by a decreased immunity, with a higher propensity for infections.26 In depressed women, an increase in hypothalmic–pituitary–adrenal activity27, 28 may lead to elevated levels of both cortisol,29 which may be associated with preterm birth, and norepinephrine,29 which may result in reduced uterine blood flow and decreased fetal growth.30 Alternatively, the negative effects of depression on pregnancy outcomes may be explained by indirect pathways, whereby substance abuse, poor nutrition and lack of volition to follow care providers’ recommendations act as mediators in the association.31, 32, 33

Strengths of our study include the large sample size, which not only allowed us to account for a number of important confounding variables, but also provided us with enough power to test for interaction between depression and excess weight. Besides BORN’s own audit, we audited the data to ensure high data quality for our key exposure variables that had not been previously assessed. Furthermore, we performed a number of a priori and post hoc sensitivity analyses in order to ensure that our findings were not merely spurious associations that resulted from inadequate data or a biased sample, and found that our original findings were in fact confirmed.

This study has limitations. First of all, despite our extensive efforts to include all appropriate confounders in our regression analyses, there is potential for residual confounding. We were unable to explore other outcomes of interest, such as infant speech and language development and cognitive test scores, because the BORN database does not collect any follow-up information after mother–infant discharge from the hospital.

We examined self-reported antenatal depression, not based on DSM-IV criteria. Although this may result in a higher proportion of women self-identifying as depressed, previous studies have shown that one- and two-question tools correlate well with clinical depression.34, 35 The prevalence we found was within the range reported in the literature,7 and perhaps most importantly, these data mirror the clinical scenario in obstetric care providers’ offices, where patients are asked about depression without using formal DSM-IV criteria. We did not have information on medication usage, which might mitigate depressive symptoms but could also potentially worsen other outcomes.

We excluded women with unknown BMI or depression status, who compared with the women included in our analyses were slightly younger, lived in neighbourhoods with a lower median family income and a greater proportion of whom were nulliparous, thus limiting the generalizability of our results. Similarly, our data set was restricted to hospitals that collected information on pre-pregnancy BMI or pre-pregnancy weight and height, thus limiting the generalizability of our results to women who delivered in hospitals that did not collect this information.

Furthermore, although there is potential for measurement bias as a result of misclassification of women’s weight status, as self-reported weight and height were used to calculate BMI, any such misclassification likely underestimates the studied associations. Research has shown that women tend to under-report their weight and over-report their height, resulting in a lower overall BMI score.36 Since this exposure misclassification is likely to be non-differential with respect to the outcome—experiencing an adverse neonatal outcome—the estimated ORs are expected to be biased towards the null, and thus the true associations may be even greater. Similarly, any misclassification of women’s depression status is also likely to be non-differential with respect to the outcome, and thus the reported associations between depression and weight status, and adverse neonatal outcomes may be underestimated.

Our findings expand the knowledge on two very important pregnancy complications, however, future research is still required to identify the impact of treated versus untreated depression, as well as the effects of overweight/obesity and depression on antenatal and intrapartum outcomes, long-term maternal and infant outcomes (for example, cognitive development), and on preterm birth stratified into spontaneous or induced, which will help inform the aetiology of disease. In summary, we found that overweight/obesity and depression combined are associated with a greater risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes than the individual risks, which has significant public health implications, given that each is at extremely high proportions. The results will help inform care providers about the potential neonatal impact, and may help to guide screening and counselling of women both pre-conception and during pregnancy.

References

Heslehurst N, Ells LJ, Simpson H, Batterham A, Wilkinson J, Summerbell CD . Trends in maternal obesity incidence rates, demographic predictors, and health inequalities in 36,821 women over a 15-year period. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2007; 114: 187–194.

Chereshneva M, Hinkson L, Oteng-Ntim E . The effects of booking body mass index on obstetric and neonatal outcomes in an inner city UK tertiary referral centre. Obstet Med 2008; 1: 88–91.

Scott-Pillai R, Spence D, Cardwell C, Hunter A, Holmes V . The impact of body mass index on maternal and neonatal outcomes: a retrospective study in a UK obstetric population, 2004-2011. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2013; 120: 932–939.

Savitz DA, Dole N, Herring AH, Kaczor D, Murphy J, Siega-Riz AM et al. Should spontaneous and medically indicated preterm births be separated for studying aetiology? Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2005; 19: 97–105.

Roman H, Goffinet F, Hulsey TF, Newman R, Robillard PY, Hulsey TC . Maternal body mass index at delivery and risk of caesarean due to dystocia in low risk pregnancies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2008; 87: 163–170.

Salihu HM, Lynch O, Alio AP, Liu J . Obesity subtypes and risk of spontaneous versus medically indicated preterm births in singletons and twins. Am J Epidemiol 2008; 168: 13–20.

Chatillon O, Even C . Antepartum depression: prevalence, diagnosis and treatment. Encephale 2010; 36: 443–451.

Molyneaux E, Poston L, Ashurst-Williams S, Howard L . Obesity and mental disorders during pregnancy and postpartum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2014; 123: 857–867.

McDonald SD, Han Z, Mulla S, Beyene J, on behalf of the Knowledge Synthesis Group. Overweight and obesity in mothers and risk of preterm birth and low birth weight infants: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ 2010; 341: c3428.

Grote NK, Bridge JA, Gavin AR, Melville JL, Iyengar S, Katon WJ . A meta-analysis of depression during pregnancy and the risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, and intrauterine growth restriction. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2010; 67: 1012–1024.

Goedhart G, Snijders AC, Hesselink AE, van Poppel MN, Bonsel GJ, Vrijkotte TG . Maternal depressive symptoms in relation to perinatal mortality and morbidity: results from a large multiethnic cohort study. Psychosom Med 2010; 72: 769–776.

Abenhaim HA, Kinch RA, Morin L, Benjamin A, Usher R . Effect of prepregnancy body mass index categories on obstetrical and neonatal outcomes. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2007; 275: 39–43.

Sebire NJ, Jolly M, Harris JP, Wadsworth J, Joffe M, Beard RW et al. Maternal obesity and pregnancy outcome: a study of 287,213 pregnancies in London. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2001; 25: 1175–1182.

Kumari AS . Pregnancy outcome in women with morbid obesity. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2001; 73: 101–107.

von EE, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP . The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet 2007; 370: 1453–1457.

Perinatal Partnership Program of Eastern and Southeastern Ontario (PPPESO). Annual Perinatal Statistical Report 2006-07. Accessed 11 July 2011. Available at https://www.nidaydatabase.com/info/pdf/200607 AnnualReportFinal.pdf. Statistics Canada. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. 2007.

The Niday Perinatal Database. Better Outcomes Registry & Network (BORN) Ontario. https://www.nidaydatabase.com 2011.

Dunn S, Bottomley J, Ali A, Walker M . 2008 Niday perinatal database quality audit: report of a quality assurance project. Chronic Dis Inj Can 2011; 32: 32–42.

Postal Code Conversion File (PCCF) 2006 Reference guide. Statistics Canada. Accessed 5 July 2011 http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/92f0153g/92f0153g2007001-eng.pdf 30-1-2007. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada., Statistics Canada. 24-10-2011.

Rubin DB . Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. Wiley: New York, 1987.

Little RJA, Rubin DB . Statistical Analysis with Missing Data 2nd edn. Wiley: New York, 2002.

Miller GJ . Lipoproteins and the haemostatic system in atherothrombotic disorders. Baillieres Clin Haematol 1994; 7: 713–732.

Retnakaran R, Hanley AJ, Raif N, Connelly PW, Sermer M, Zinman B . C-reactive protein and gestational diabetes: the central role of maternal obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003; 88: 3507–3512.

Madan JC, Davis JM, Craig WY, Collins M, Allan W, Quinn R et al. Maternal obesity and markers of inflammation in pregnancy. Cytokine 2009; 47: 61–64.

Nohr EA, Bech BH, Vaeth M, Rasmussen KM, Henriksen TB, Olsen J . Obesity, gestational weight gain and preterm birth: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Paediatr Perinatal Epidemiol 2007; 21: 5–14.

Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry 2010; 67: 446–457.

Rich-Edwards JW, Mohllajee AP, Kleinman K, Hacker MR, Majzoub J, Wright RJ et al. Elevated midpregnancy corticotropin-releasing hormone is associated with prenatal, but not postpartum, maternal depression. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 1946–1951.

Kammerer M, Taylor A, Glover V . The HPA axis and perinatal depression: a hypothesis. Arch Womens Ment Health 2006; 9: 187–196.

Diego MA, Jones NA, Field T, Hernandez-Reif M, Schanberg S, Kuhn C et al. Maternal psychological distress, prenatal cortisol, and fetal weight. Psychosom Med 2006; 68: 747–753.

Stevens AD, Lumbers ER . Effects of intravenous infusions of noradrenaline into the pregnant ewe on uterine blood flow, fetal renal function, and lung liquid flow. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 1995; 73: 202–208.

Nagahawatte NT, Goldenberg RL . Poverty, maternal health, and adverse pregnancy outcomes. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008; 1136: 80–85.

Norbeck JS, Tilden VP . Life stress, social support, and emotional disequilibrium in complications of pregnancy: a prospective, multivariate study. J Health Soc Behav 1983; 24: 30–46.

Coverdale JH, Chervenak FA, McCullough LB, Bayer T . Ethically justified clinically comprehensive guidelines for the management of the depressed pregnant patient. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1996; 174: 169–173.

Chochinov HM, Wilson KG, Enns M, Lander S . "Are you depressed?" Screening for depression in the terminally ill. Am J Psychiatry 1997; 154: 674–676.

Whooley MA, Avins AL, Miranda J, Browner WS . Case-finding instruments for depression. Two questions are as good as many. J Gen Intern Med 1997; 12: 439–445.

Gosse MA . How accurate is self-reported BMI? Nutr Bull 2014; 39: 105–114.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Regional Medical Association (RMA) grant, and Sarah D McDonald is supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) New Investigator Award # CNl 95357. RMA and CIHR had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDonald, S., McKinney, B., Foster, G. et al. The combined effects of maternal depression and excess weight on neonatal outcomes. Int J Obes 39, 1033–1040 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.44

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.44

This article is cited by

-

Maternal body mass index moderates antenatal depression effects on infant birthweight

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Antenatal and postnatal depression in women with obesity: a systematic review

Archives of Women's Mental Health (2017)

-

Time trends and risk factor associated with premature birth and infants deaths due to prematurity in Hubei Province, China from 2001 to 2012

BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth (2015)

-

Pregnancy complications associated with the co-prevalence of excess maternal weight and depression

International Journal of Obesity (2015)