Abstract

Objectives:

The optimal screening measures for obesity in children remain controversial. Our study aimed to determine the anthropometric measurement at age 10 years that most strongly predicts the incidence of cardio-metabolic risk factors at age 13 years.

Subjects/Methods:

This was a prospective cohort study of a population-based cohort of 438 children followed between age 7 and 13 years of age. The main exposure variables were adiposity at age 10 years determined from body mass index (BMI) Z-score, waist circumference (WC) Z-score, waist-to-hip ratio and waist-to-height ratio. Outcome measures included systolic (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP), fasting high-density (HDL-c) and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-c), triglycerides, insulin and glucose (homeostasis model of assessment, HOMA), and the presence of metabolic syndrome (MetS).

Results:

WC Z-score at age 10 years was a stronger predictor of SBP (β 0.21, R2 0.38, P<0.001 vs β 0.30, R2 0.20, P<0.001) and HOMA (β 0.51, R2 0.25, P<0.001 vs 0.40, R2 0.19, P<0.001) at age 13 years compared with BMI Z-score. WC relative to height and hip was stronger predictors of cardio- metabolic risk than BMI Z-score or WC Z-score. The relative risk (RR) of incident MetS was greater for an elevated BMI Z-score than for an elevated WC (girls: RR 2.52, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.46–4.34 vs RR 1.56, 95% CI 1.18–2.07) and (boys: RR 2.86, 95% CI 1.79–4.62 vs RR 2.09, 95% CI 1.59–2.77).

Conclusions:

WC was a better predictor of SBP and HOMA compared with BMI or WC expressed relative to height or hip circumference. BMI was associated with higher odds of MetS compared with WC. Thus, BMI and WC may each be clinically relevant markers of different cardio-metabolic risk factors, and important in informing obesity-related prevention and treatment strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over the last several decades, obesity has become an increasingly prevalent threat to the health of adults and children in the developed and developing world.1, 2, 3 Overweight and obesity are associated with several cardio-metabolic diseases in adults including hypertension, dyslipidemia, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, polycystic ovarian syndrome, coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes.4, 5, 6 The presence of adverse changes in cardiac and vascular function and type 2 diabetes in children illustrates the importance of clinical measures of obesity-related cardio-metabolic disease risk in the pediatric population.7, 8, 9

The method used to classify youth as overweight or obese is a controversial topic for several reasons. First, BMI percentiles used to define ‘overweight’ and ‘obese’ in children are not based on an increased risk of cardiometabolic endpoints.10, 11, 12, 13 Second, it is unclear whether a measure of general obesity and central obesity is the appropriate method to assess obesity-related cardiometabolic risk. Some studies suggest that a measure of waist circumference (WC) does not provide additional prognostic value for cardio-metabolic risk.14, 15, 16 In contrast, other studies suggest that WC is a robust predictor of insulin resistance, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) concentrations and blood pressure independent of BMI.17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22

The primary objective of this study was to compare the performance of clinical measures of obesity: BMI Z-score, WC Z-score, waist-to-hip ratio and waist-to-height ratio at 10 years of age in predicting cardio-metabolic risk at 13 years of age in a longitudinal birth cohort of Manitoban children. A secondary objective of the study was to determine whether risk prediction could be increased by a combination of these anthropometric measures. Finally, a third objective was to determine whether the anthropometric measures perform differently in risk prediction based on sex.

Materials and methods

Population

Data were extracted from the longitudinal follow-up of the 1995 SAGE birth cohort in Manitoba, Canada.23 Of the 16 320 children born in Manitoba in 1995, 13 980 (~86%) remained in the province at the start of the study in 2002. Participants were recruited through mail out questionnaire. In total, 3598 surveys were returned (~26%) and 800 participants (6%) were invited to participate from a random sampling of rural, urban and northern First Nation reserve locations. Of the 800 invitees, 723 (90%) parents agreed to participate. Participants were evaluated at ages 8, 10 and 13 years. Data collected at the 10- and 13-year visit included: anthropometric measures including height, weight, waist and hip circumference, blood pressure and fasting blood work (lipid profile, insulin and glucose levels). Additional data collected at age 8 years (initial cohort visit) included: self-reported ethnicity, household income, maternal education, diagnosis of asthma and medication use. All participants who had complete anthropometric data at age 10 years and 13 years and complete cardiometabolic data at 13 years were included in the study.

All children provided written assent and parents consented to participation in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The Human Research Ethics Board of the University of Manitoba, Canada granted ethical approval.

Exposure variables

The primary exposure variables were BMI Z score, WC and waist relative to height and hip circumference. BMI calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (meters). BMI was calculated from measurements of height and weight. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm in triplicate without shoes on a standardized clinical Harpenden stadiometer with an average of three measures recorded. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kilogram in triplicate on a standard clinical grade electronic scale with an average of the three measures recorded. BMI Z-scores were calculated from the age- and sex-specific means and standard deviations of the US CDC reference population.24 Overweight and obesity were classified on BMI Z-score age- and sex-specific cut points published in the International task force on obesity guidelines.25 WC was measured against the skin at the natural waist (midpoint between the top of the iliac crest and the lower ribs) with a non-elastic flexible tape measure. WC Z-scores were calculated from age- and sex-specific means and standard deviations from a Canadian reference population.26 Canadian standardized reference data for WC have been determined by measurements at the narrowest point of the waist. The difference between study and standard measurement techniques was the same for all children and not expected to significantly impact the relationship between waist measures as Z-scores and metabolic outcomes. Waist- to-hip ratios and waist-to-height ratios were calculated and analyzed as continuous variables.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome variables were systolic blood pressure (SBP), serum lipoproteins, insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome (MetS). Blood pressure was measured in triplicate on the right arm sitting at rest using a Dynamap automated sphygmomanometer (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) with an appropriately sized blood pressure cuff. An average of the three readings was recorded.

The MetS was treated as a binary outcome using cut points for SBP, serum triglycerides, WC, fasting glucose and low high density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) that were statistically derived to reflect cut points in adults.27 Adolescents were classified as having the MetS if they had three or more of five co-morbidities.

Serum samples were collected in the morning following a 10-h fast. Plasma glucose was measured on a Roche Modular P analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) with a UV test principle (hexokinase method). Insulin was measured on an Immulite, solid-phase, two-site chemiluminescent immunometric assay. Serum lipoproteins and triglycerides were measured on a Roche Modular P analyzer. LDL-c was calculated using the Friedwald equation (LDL-c=total cholesterol−(HDL-c−(TG/2.2))). Homeostasis model of assessment (HOMA) was calculated from fasting serum insulin and glucose levels as a measure of insulin sensitivity.28

Confounding variables

Confounding variables were determined a priori through a review of the literature. Pubertal status was classified as prepubertal or pubertal using serum levels of estrogen (⩽50 pmol l−1 prepubertal) and testosterone (⩽1.0 prepubertal) in conjunction with a self-dministered Tanner stage questionnaire. Asthma was diagnosed on a clinical basis by a physician at each visit and was coded as present or absent. Ethnicity was self-reported on parental questionnaires. If either parent declared First Nations (n=78) or Metis (n=6) ethnicity, then the child was coded as Indigenous. The remaining population self-declared as Caucasian (n=625) or Filipino (n=13) and these two groups were collapsed into a non-Indigenous category. Maternal education and household income were self-reported on a multiple choice questionnaire. Educational attainment was divided based on two categories, high school diploma completed (yes/no) and post-secondary education completed (yes/no). Annual household income brackets included: (a) <$10 000, (b) $10 000–19 999, (c) $20 000–29 999, (d) $30 000–39 999, (e) $40 000–49 999, (f) $50 000–59 999, (g) $60 000–69 999, (h) $70 000–79 999 and (i) ⩾$80 000. Income was then divided into three subgroups for the purposes of this study; (a) $0–39 999, (b) $40 000–69 999 and (c) ⩾$70 000. Statistics comparing the effect of the original income brackets with the newly formed brackets did not reveal a difference.

Statistical analysis

Sample size

This was a pre-existing data set therefore sample size for the data set was predetermined. All of the data available was used in the current analysis to increase the power of the study. Post hoc power analysis was done to determine whether subgroup analysis of sexes would be adequately powered (>80%) to detect clinically significant differences in the outcome MetS (event rate at the population mean BMI, 2% vs event rate at a BMI 2 standard deviations above the mean, 20%); rates determined from previously published Manitoba cohorts with 20% missing data, two-tailed alpha 0.05 and n=200 participants (available n for each of the sexes) the power was 86%. Similar sample size was calculated using the means and s.d. of WC measures assuming an increase in WC by 2s.d. would increase the event rate from 1 to 20%. Sample size analysis was performed with SPSS samplepower software (V 3.0.0) (IBM Canada, Markham, ON, Canada).

Descriptive analysis

All data were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Cross-sectional univariate analyses were performed to evaluate the association of each individual anthropometric measure on its original scale on each of the cardio-metabolic outcomes at ages 10 and 13 years. Strength of correlation between anthropometric measures and each of the outcome measures was assessed by the Pearsons correlation coefficients.

MetS was treated as a binary outcome measure and multivariable logistic regression analysis was performed to test for associations between various measures of adiposity, adjusting for confounders. Final regression analyses were adjusted for a priori identified confounders including: age at time of the risk factor measurements, asthma diagnosis, ethnicity, maternal education, annual household income and pubertal stage. Regression analyses adjusting for the effects of other measures of adiposity were done to identify the independent effects of each clinical measure. To examine whether a combination of adiposity measures would outperform each measure individually, a multivariate linear regression was performed by adding each measure sequentially to a base model adjusted for potential confounders (age, ethnicity, asthma, income, maternal education, pubertal status). Collinearity within the models with >1 anthropometric measure included was examined. For models with tolerance <0.2, the anthropometric measure with the weaker association was removed.

Missing data

Subjects with missing data in any one of the five components of the MetS (HDL-c, LDL-c, SBP, DBP and Glucose) were excluded from the final logistic regression analysis (n=28). The group of subjects with missing data at age 13 years had a higher proportion of First Nations participants and lower maternal education. There was no difference between subjects with and without missing data at age 13 years for any of the anthropometric measures or pubertal measures. Examination of patterns of missing data revealed most missing data were consistent with a subject not completing the final study visit at all (n=18 ) or completing the clinical but not laboratory measures (n=10), thus variables were not missing at random as laboratory values tended to be missing together. Analysis of a complete data set using multiple imputations for missing data resulted in similar significant relationships as reported in this manuscript.

Statistical analysis was performed using STATA version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and SPSS (for missing values analysis and sample size calculations).

Results

Participant characteristics

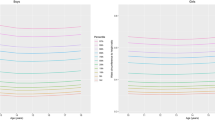

Participant characteristics are provided in Table 1. Among the youth retained in the final analysis, 56% were boys, 24.1% (136/563) were overweight and 11.7% (66/563) were obese at age 10 years, while 23.9% (105/438) were overweight and 12.6% (55/438) were obese at age 13 years. Measures of adiposity for each participant at 10 and 13 years did not differ significantly from one visit to the next demonstrating tracking of adiposity measures from childhood into adolescence.

None of the participants met the criteria for the MetS at the 10-year visit. Incidence of the MetS at age 13 years was 15.1 and 12.7% in boys and girls, respectively. Significant differences between the sexes were identified in weight Z-score at 10 years (P=0.01), waist-to-hip ratio at 10 years (P<0.001) and 13 years (P<0.001), and WC at age 10 years (P<0.05). Waist-to-height ratio was not significantly different between the sexes. As expected, stage of puberty significantly differed between the sexes with more girls than boys attaining pubertal status at both ages 10 years (75.6 vs 38.2%, P<0.001) and 13 years (94.2 vs 61.7%, P<0.001) (Table 1). Boys displayed lower serum triglycerides at age 10 years (P=0.03) and HOMA (P=0.01) and SBP (P=0.04) at 13 years compared with girls (Table 2).

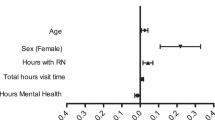

Multivariable linear regression of measures of adiposity on metabolic risk

BMI Z-score (β 0.30, P<0.001) and WC Z-score (β 0.21, P 0.001) were significant predictors of SBP in girls (Table 3). In boys, BMI Z-score (β 0.23, P<0.001), WC Z-score (β 0.43, P<0.001), waist-to-hip ratio (β 0.20, P 0.002) and waist-to-height ratio (β 0.28, P<0.001) were all significant predictors of SBP (Table 4). When HOMA was predicted in both boys and girls all anthropometric measures were found to be significant predictors (Tables 3 and 4). When fasting lipids were predicted in girls, HDL-c and triglycerides were predicted by BMI Z-score (β −0.27, P<0.001; β 0.27, P 0.003), WC Z-score (β −0.37, P<0.001; β 0.30, P 0.002) and waist-to-height ratio (β −0.38, P<0.001; β 0.42, P<0.001). Diastolic blood pressure (DBP) and LDL-c were not significantly predicted by any of the anthropometric variables in girls. In boys, LDL-c, HDL-c and triglycerides were predicted by BMI Z-score (β 0.14, P<0.02; β 0.14, P<0.001; β 0.31, P<0.001), WC Z-score (β 0.26, P<0.001; β −0.42, P<0.001; β 0.43, P<0.001), waist-to-hip ratio (β 0.28, P<0.001; β −0.27, P<0.001; β 0.35, P<0.001) and waist-to-height ratio (β 0.29, P<0.001; β −0.38, P<0.001; β 0.42, P<0.001).

When comparing predictive capacity of the different anthropometric measures between the sexes, LDL-c was significantly predicted by WC Z-score (β 0.26, P 0.001), and waist-to-hip ratio (β 0.28, P<0.001) in boys only. Waist-to-hip and waist-to-height ratios did not perform better at predicting any of the cardio-metabolic risk factors than either BMI Z-score or WC Z-score.

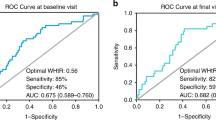

The odds of having the MetS at age 13 years in girls was 2.52 times higher (95% confidence interval (CI): 1.46,4.34, P<0.001), and in boys was 2.86 times higher (95% CI 1.79, 4.62, P<0.001), for every incremental increase in BMI Z-score at age 10–11 years (Table 5). The odds of having the MetS at age 12–13 years in girls was 1.56 times higher (95% CI: 1.18, 2.07, P<0.002), and in boys was 2.09 times higher (95% CI 1.59, 2.77, P<0.001), for every incremental increase in WC score at age 10–11 years (Table 6).

Discussion

In children, all three measures of adiposity were independently associated with components of cardiovascular risk and the MetS. In general, anthropometric measurements were better predictors of higher SBP, lower HDL-c and higher measures of insulin resistance (HOMA) than for higher DBP, higher LDL cholesterol and serum triglyceride levels for both boys and girls. This suggests a differential influence of adiposity on different cardio-metabolic risk factors. In addition, WC accounted for a larger proportion of the variance in SBP and of insulin resistance (as measured by HOMA) compared with BMI Z-score suggesting that the distribution of adiposity may have a larger role in the development of these specific risk factors.

A gender difference was seen in the ability of the anthropometric measures to predict individual cardio-metabolic risk factors. Waist-based measurements at age 10 years performed better in boys than in girls in predicting higher LDL-c, lower HDL-c and higher triglycerides at age 13 years. Additionally, the relative risk of developing the MetS related to each of the anthropometric measures was greater in boys than in girls. The importance of adiposity and specifically, central adiposity, on cardio-metabolic risk appears to be different for boys and girls, a finding that persisted even when models were controlled for the differences in pubertal status between the sexes.

Waists-to-hip ratio measurements were no better than WC Z-score alone in accounting for the variance in any of the risk factors. This is likely due to the additional error introduced by having two separate measurements as components of this measure. Our analysis did not demonstrate any significant improvement in predictive capability by the addition of one anthropometric measure to the other (BMI Z-score plus WC). However, there was a difference in which measure had a stronger predictive capacity of individual outcomes with WC being retained in the models for SBP, serum HDL cholesterol and insulin resistance (HOMA).

Our findings are consistent with other studies demonstrating overweight and obesity track throughout childhood into adolescence and are associated with increases in prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in adolescence. In contrast to several other prospective longitudinal cohort studies in children,14, 16 our study found that WC measures were a stronger predictor of increased SBP, insulin resistance and lower HDL cholesterol suggesting that it is a clinically important measure in children to predict future risk. This is consistent with other cross-sectional studies in pediatrics identifying WC as an independent predictor of insulin resistance,21 lipid profiles29 and a clustering of cardio-metabolic risk factors.30 It is possible that the differences in pubertal stage when the cardio-metabolic risk factors are measured influence the role of each anthropometric measurement. Previous studies have identified strong influences of puberty on distributions of adiposity and development of insulin resistance and the MetS.31, 32, 33 A large proportion of our children were prepubertal when assessed at a mean age of 10 years and in early puberty when assessed at a mean age of 13 years, whereas the previous longitudinal studies assessed outcomes at age 15 years which is late in puberty.

In addition, the other prospective studies used longitudinal birth cohorts where data had been collected in several different sites potentially adding to the inherent individual variability for measuring WC. Our study was a smaller birth cohort study in a single province with all participants coming into a single clinical research center for measurements by the same two research coordinators trained on WC and hip circumference measurements. This may have improved the performance of waist-based measures to predict some of the cardio-metabolic risks.

This study was conducted on a large population-based sample. This is the population for which clinically simple and reliable anthropometric measures of risk such as BMI Z-score and WC are needed. In addition, data were available for a variety of confounders including proxy measures for socioeconomic status, which is known to influence cardio-metabolic risk.

A limitation of the study is the loss to follow-up at age 13 years with only 67.6% of the original cohort of children having complete outcome data at the 13-year visit. Missing data analysis suggested participants and those lost to follow-up were not different in terms of the measured baseline values. However, we cannot account for any differences in unmeasured factors, which may influence adiposity or cardio-metabolic risk. As this study was a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data other variables including maternal and paternal BMI, and birth weight, which are known to influence childhood adiposity could not be examined or adjusted for. The purpose of this study however was to determine a clinical marker of cardio- metabolic risk and therefore even if the anthropometric measure was a marker of a different causative factor, if it is a consistent marker then it will be clinically useful. The small number of youth at age 13 years who met criteria for the MetS may have influenced our ability to determine the effect of each anthropometric measure on the odds of meeting the MetS criteria at age 13 years.

This study reports important prospective associations of both WC and BMI Z-score at 10 years of age and the prediction of the presence of cardio-metabolic risk factors at 13 years of age. Currently, many national guidelines on the prevention, evaluation and management of overweight and obesity in childhood only recommend BMI as an indication of overweight and obesity.10, 11, 12 Indeed many guidelines suggest screening for obesity-related complications including type 2 diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidemia based on BMI cut points.10, 12 Our study adds to the evidence that WC has clinical utility in the evaluation of overweight and obesity in youth, supporting its inclusion in the routine primary care evaluation of children. Importantly, our results suggest that WC is a better predictor of elevated SBP and insulin resistance than BMI and may be a more important measure to define the risk of hypertension and T2DM in children. Our study also demonstrated a differential risk for adverse health outcomes conferred by central adiposity compared with whole body adiposity. In addition, these risks appear to be different for boys and girls, with additional predictive capacity of waist-based measures for LDL-cholesterol in boys only.

Our study adds to the current growing body of knowledge regarding childhood clinical markers of future cardio-metabolic risk, and extends this literature with the addition of more recent anthropometric measures of risk (waist-to-hip and waist-to-height ratio). These findings can inform future standard clinical practice guidelines, and education (messaging) to families, and future research in childhood obesity. Waist-based measures may be more appropriate exposure measures in certain ages and pubertal stages to assess future weight-related morbidity. Future studies investigating the role of interventions to reduce waist-based measures and effect outcomes such as metabolic and cardiovascular risk will be an important next step to determine how WC in childhood affects an individual’s long-term health.

References

Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, Gobin R, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet 2010; 375: 2215–2222.

Selassie M, Sinha AC . The epidemiology and aetiology of obesity: a global challenge. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol 2011; 25: 1–9.

Leiter LA, Fitchett DH, Gilbert RE, Gupta M, Mancini GB, McFarlane PA et al. Identification and management of cardiometabolic risk in Canada: a position paper by the cardiometabolic risk working group (executive summary). Can J Cardiol 2011; 27: 124–131.

Grundy SM . Pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk. JACC 2012; 59: 635–643.

Prasad H, Ryan DA, Celzo MF, Stapleton D . Metabolic syndrome: definition and therapeutic implications. Postgrad Med 2012; 124: 21–30.

Biro FM, Wien M . Childhood obesity and adult morbidities. Am J Clin Nutr 2010; 91: 1499S–1505S.

Wen LM, Baur LA, Simpson JM, Rissel C, Wardle K, Flood VM . Effectiveness of home based early intervention on children's BMI at age 2: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2012; 344: e3732.

Capizzi M, Leto G, Petrone A, Zampetti S, Papa RE, Osimani M et al. Wrist circumference is a clinical marker of insulin resistance in overweight and obese children and adolescents. Circulation 2011; 123: 1757–1762.

Tremblay MS . Major initiatives related to childhood obesity and physical inactivity in Canada: the year in review. Can J Public Health 2012; 103: 164–169.

Lau DC, Douketis JD, Morrison KM, Hramiak IM, Sharma AM, Ur E . 2006 Canadian clinical practice guidelines on the management and prevention of obesity in adults and children [summary]. CMAJ 2007; 176: S1–13.

Pemberton VL, McCrindle BW, Barkin S, Daniels SR, Barlow SE, Binns HJ et al. Report of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute's Working Group on obesity and other cardiovascular risk factors in congenital heart disease. Circulation 2010; 121: 1153–1159.

August GP, Caprio S, Fennoy I, Freemark M, Kaufman FR, Lustig RH et al. Prevention and treatment of pediatric obesity: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline based on expert opinion. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2008; 93: 4576–4599.

Logue J, Thompson L, Romanes F, Wilson DC, Thompson J, Sattar N . Management of obesity: summary of SIGN guideline. BMJ 2010; 340: c154.

Garnett SP, Baur LA, Srinivasan S, Lee JW, Cowell CT . Body mass index and waist circumference in midchildhood and adverse cardiovascular disease risk clustering in adolescence. Am J Clin Nutr 2007; 86: 549–555.

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Srinivasan SR, Chen W, Malina RM, Bouchard C et al. Combined influence of body mass index and waist circumference on coronary artery disease risk factors among children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2005; 115: 1623–1630.

Lawlor DA, Benfield L, Logue J, Tilling K, Howe LD, Fraser A et al. Association between general and central adiposity in childhood, and change in these, with cardiovascular risk factors in adolescence: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2010; 341: c6224.

Tybor DJ, Lichtenstein AH, Dallal GE, Daniels SR, Must A . Independent effects of age-related changes in waist circumference and BMI z scores in predicting cardiovascular disease risk factors in a prospective cohort of adolescent females. Am J Clin Nutr 2011; 93: 392–401.

Janssen I, Katzmarzyk PT, Ross R . Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. Am J Clin Nutr 2004; 79: 379–384.

Maffeis C, Pietrobelli A, Grezzani A, Provera S, Tato L . Waist circumference and cardiovascular risk factors in prepubertal children. Obes Res 2001; 9: 179–187.

Maffeis C, Banzato C, Talamini G . Waist-to-height ratio, a useful index to identify high metabolic risk in overweight children. J Pediatr 2008; 152: 207–213.

Lee S, Bacha F, Gungor N, Arslanian SA . Waist circumference is an independent predictor of insulin resistance in black and white youths. J Pediatr 2006; 148: 188–194.

Khoury M, Manlhiot C, Dobbin S, Gibson D, Chahal N, Wong H et al. Role of waist measures in characterizing the lipid and blood pressure assessment of adolescents classified by body mass index. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2012; 166: 719–724.

Kozyrskyj AL, HayGlass KT, Sandford AJ, Pare PD, Chan-Yeung M, Becker AB . A novel study design to investigate the early-life origins of asthma in children (SAGE study). Allergy 2009; 64: 1185–1193.

Statistics USA: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES): Z-Score Reference for Height, Weight and BMI. http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts Height; Accessed June 2012.

Cole TJ, Bellizzi MC, Flegal KM, Dietz WH . Establishing a standard definition for child overweight and obesity worldwide: international survey. BMJ 2000; 320: 1240–1243.

Katzmarzyk PT . Waist circumference percentiles for Canadian youth 11-18y of age. Eur J Clin Nutr 2004; 58: 1011–1015.

Jolliffe CJ, Janssen I . Development of age-specific adolescent metabolic syndrome criteria that are linked to the Adult Treatment Panel III and International Diabetes Federation criteria. JACC 2007; 49: 891–898.

Ginsberg HN . Insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease. J Clin Invest 2000; 106: 453–458.

Flodmark CE, Sveger T, Nilsson-Ehle P . Waist measurement correlates to a potentially atherogenic lipoprotein profile in obese 12-14-year-old children. Acta Paediatr 1994; 83: 941–945.

Savva SC, Tornaritis M, Savva ME, Kourides Y, Panagi A, Silikiotou N et al. Waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio are better predictors of cardiovascular disease risk factors in children than body mass index. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 2000; 24: 1453–1458.

Agatston A . Cardiology patient page. Why America is fatter and sicker than ever. Circulation 2012; 126: e3–e5.

Staiano AE, Katzmarzyk PT . Ethnic and sex differences in body fat and visceral and subcutaneous adiposity in children and adolescents. Int J Obes (2005) 2012; 36: 1261–1269.

Stockl D, Meisinger C, Peters A, Thorand B, Huth C, Heier M et al. Age at menarche and its association with the metabolic syndrome and its components: results from the KORA F4 study. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e26076.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the children and their families for their participation in the SAGE cohort study. We would also like to thank the Pediatric allergy and immunology research group specifically, Mrs Rishma Choonidas, Mr Saiful Huq, Mrs Brenda Gerwing and Mr Henry Huang who provided insight and guidance into data collection, storage and interpretation. Funding for the SAGE cohort was provided by CIHR and AllerGen NCE (PIs Becker and Kozyrskyj wave 1 data collection; Co-PI Becker wave 2 data collection).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wicklow, B., Becker, A., Chateau, D. et al. Comparison of anthropometric measurements in children to predict metabolic syndrome in adolescence: analysis of prospective cohort data. Int J Obes 39, 1070–1078 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.55

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ijo.2015.55

This article is cited by

-

Sociodemographic characteristics are associated with prevalence of high-risk waist circumference and high-risk waist-to-height ratio in U.S. adolescents

BMC Pediatrics (2021)

-

Predictors of Metabolic Complications in Obese Indian Children and Adolescents

The Indian Journal of Pediatrics (2021)

-

Association of breastfeeding duration, birth weight, and current weight status with the risk of elevated blood pressure in preschoolers

European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2020)

-

Gender-specific mediators of the association between parental education and adiposity among adolescents: the HEIA study

Scientific Reports (2019)

-

Genetic contribution to waist-to-hip ratio in Mexican children and adolescents based on 12 loci validated in European adults

International Journal of Obesity (2019)