Abstract

As globalization and cultural diversity continue to evolve, donation behavior in cultural heritage preservation has gained increasing importance. However, existing studies primarily focus on economic incentives, often overlooking the roles of intrinsic psychological motivations and cultural adaptability. This study integrates the Theory of Planned Behavior to explore how generativity, cultural intelligence, and intergenerational differences are related to donation behavior. Using stratified random sampling, 1463 valid samples were collected, and PLS-SEM analysis was employed to examine both the direct and indirect associations between generativity, cultural intelligence, and donation behavior. The results show that cultural intelligence acts as a mediating variable, illustrating the relationship between generativity and donation intentions and behavior, and as a moderating variable, enhancing the impact of subjective norms on donation behavior. Additionally, generativity is positively related to donation behavior and enhances donation intentions by increasing cultural intelligence. The older generation is more likely to donate, as cultural intelligence and generativity are positively associated with donation intentions and behavior, while younger generations place more emphasis on cultural intelligence when making donation decisions. This study introduces the “Cultural Generativity Behavior Model,” incorporating cultural intelligence and generativity into the framework of cultural heritage donation behavior and extending TPB. It highlights the mediating role of cultural intelligence between generativity and donation behavior and demonstrates the moderating effect of intergenerational differences on the relationship between cultural intelligence and donation behavior, further expanding the applicability of TPB across different age groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultural heritage connects history, culture, and modern society, reflecting the cultural, social, and historical values of communities1. With increasing globalization, the preservation of heritage is crucial not only for maintaining history but also for fostering cultural identity and social cohesion2,3. However, globalization, urbanization, and growing pressure from tourism have led to irreversible damage at many cultural heritage sites4. Despite growing public awareness of heritage preservation, funding shortages remain a major challenge in cultural heritage protection, particularly in areas where government resources are limited or tourism-driven revenue falls short of preservation needs5,6,7.

Encouraging donation behavior among local residents and stakeholders is a practical approach to supporting preservation efforts8,9,10. In the context of cultural heritage, donation behavior is influenced by a complex interplay of psychological, cultural, and social factors11. Existing literature primarily focuses on psychological factors such as emotional attachment, cultural attitudes, perceived value, and community engagement12,13,14,15. However, there is limited research exploring how residents form donation intentions through complex psychological motivations and socio-cultural adaptation16,17. While many studies examine economic drivers or environmental attitudes in heritage donations, research on psychological and socio-cultural factors, particularly intergenerational differences, remains sparse18,19. This gap partly stems from traditional top-down approaches in cultural heritage management, which often overlook in-depth studies of residents’ intrinsic psychological motivations and cultural adaptability.

To fill this gap, this study introduces two core concepts: generativity and cultural intelligence. Generativity, rooted in developmental psychology, refers to the desire to guide and contribute to future generations and is increasingly recognized as a critical motivator for prosocial behavior20. In the context of cultural heritage, individuals with high generativity may view their contributions as a legacy for future generations, thereby increasing their willingness to donate to preservation efforts19,21.

Importantly, generativity and cultural intelligence are interconnected, and there may be a mediating relationship between the two. Research suggests that generativity may influence attitudes toward cultural heritage preservation and donation behavior indirectly by enhancing individuals’ cultural intelligence22,23,24. Cultural intelligence, in turn, helps individuals adapt to multicultural environments and could transform intrinsic motivations into concrete behaviors, such as donations for heritage preservation25,26,27. However, this mediating role of cultural intelligence remains largely unexplored, particularly in multicultural settings, and represents a significant research gap.

Further complicating the issue are intergenerational differences28. Existing research often treats residents as a homogeneous group, overlooking variations in generativity and cultural intelligence across generational cohorts. Studies indicate that different generational groups may have distinct perceptions of cultural heritage and varying psychological mechanisms (e.g., emotional or place attachment), which can influence their support for tourism development and cultural preservation19,29,30. However, the impact of generativity and cultural intelligence on donation behavior across generations has received limited attention. Therefore, understanding the moderating role of intergenerational differences is crucial in examining these influences.

To fill the aforementioned research gaps, the objectives of this study are as follows:

-

(1)

To explore the pathway relationships between psychological and cultural factors (generativity and cultural intelligence) and residents’ donation behavior in cultural heritage preservation.

-

(2)

To examine the moderating mechanism of intergenerational differences in the influence of generativity and cultural intelligence on behavioral attitudes.

-

(3)

To analyze the mediating effect of cultural intelligence between generativity and donation behavior, and further investigate how this mediation manifests across different generational groups.

-

(4)

To construct a behavioral model from a cultural and psychological perspective, based on the Theory of Planned Behavior, integrating the core elements of intergenerational differences, generativity, and cultural intelligence, and revealing their complex influence pathways on donation behavior in cultural heritage preservation.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a detailed literature review on generativity, cultural intelligence, and donation behavior. Section 3 outlines the research design and methodology. Section 4 presents the results and discussion. Finally, Section 5 concludes with the study’s conclusions and future outlook.

Literature review and research hypotheses

Theory of planned behavior and donations for cultural heritage

Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB), proposed by31, is a well-established framework that predicts individual behavioral decisions across various domains. The model has been applied in a range of fields, including health32, environmental science33, tourism management34, and education35. In environmental protection, TPB helps explain psychological motivations for pro-environmental behavior36,37 and public support for policies.

In the field of cultural heritage preservation, TPB has been effectively used to analyze the intentions and behaviors of residents, particularly regarding their donation behaviors. For example38, examined how place attachment, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control influence residents’ attitudes and intentions39. extended TPB to examine the relationship between collective characteristics and individual behavior in community renewal. while18 focused on cultural heritage donation behavior, highlighting the importance of subjective norms and perceived behavioral control.

Although Behavioral Intention (BI) is a strong predictor of behavior, there is often a gap between intention and action. This intention-behavior gap is particularly evident in cultural heritage donations, where many residents express strong intentions to donate but fail to follow through40,41. Understanding what factors convert intentions into actions is critical for addressing this gap. TPB identifies Attitude (AB), Subjective Norms (SN), and Perceived Behavioral Control (PBC) as key determinants of BI, with PBC also directly influencing Donation Behavior (DB)31. Addressing this gap is essential for developing effective cultural heritage preservation strategies. In this context, individuals with positive attitudes toward cultural preservation are more likely to form strong intentions to donate18,39, especially when they place higher value on cultural heritage. Consequently, we hypothesize that:

H1: AB is positively related to BI.

Similarly, SN, which reflect the social pressures perceived by individuals regarding the behavior in question, are significant predictors of BI. TPB suggests that when individuals believe others (family, peers, or society) expect them to engage in a behavior, they are more likely to follow through with that behavior. In the context of cultural heritage donations, individuals are more likely to form intentions to donate if donating is perceived as a normative behavior31. Thus, we hypothesize that:

H2: SN are positively related to BI.

Finally, PBC plays a crucial role in shaping BI and determining whether individuals feel capable of performing the behavior. In DB, when individuals perceive they have the necessary resources or means to contribute, they are more likely to form the intention to donate42. Research has shown that higher levels of perceived control over the donation process increase the likelihood of forming BI18. Therefore, we hypothesize that:

H3: PBC is positively related to BI.

Lastly, BI is a robust predictor of actual behavior. Individuals with stronger intentions are more likely to follow through with their intended behavior, assuming no significant external barriers exist31,42. In the context of cultural heritage donations, individuals with stronger intentions are more likely to follow through with their donations, leading us to hypothesize that:

H4: BI is positively related to DB.

The influence of psychological and cultural factors

Although the TPB model is widely applied to explain individual behavior, relying solely on TPB cannot fully account for the more complex psychological and cultural factors involved in cultural heritage DB42. Therefore, this study introduces Generativity (G) and Cultural Intelligence (CQ) as additional variables to provide a more comprehensive explanation of DB in cultural heritage preservation. G reflects individuals’ emphasis on intergenerational responsibility, which may shape their donation motivations, while CQ represents their ability to adapt in multicultural contexts, potentially enhancing their understanding of cultural heritage values and willingness to protect them. By incorporating these concepts, this paper presents a theoretical framework that better captures the psychological and cultural factors influencing DB.

Generativity and its impact on behavior

G refers to individuals’ concern for future generations and their desire to ensure a positive legacy through actions like creation, guidance, and education43,44. expanded on this concept, proposing multiple dimensions, including cultural demand, generative desire, generative concern, belief in the species, commitment, generative action, and personal narration.

Generativity not only reflects individuals’ contributions to their family but also encompasses a broader sense of social responsibility and cultural transmission. For example45, found that individuals with high levels of G are more likely to demonstrate greater awareness of environmental issues, which could motivate them to take proactive actions, such as participating in environmental protection activities or donating resources46. further examined how G relates to AB and behaviors, especially in the realm of social responsibility.

In cultural heritage preservation, G is considered an important psychological driver that is associated with residents’ participation in preservation activities. For instance21, found that individuals with higher levels of G tend to engage in cultural heritage preservation activities, as it fulfills their need for self-actualization and enhances their sense of social responsibility19. found that individuals with strong G are more likely to support cultural heritage preservation through donations or other contributions. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H5: G is positively related to AB.

Cultural intelligence and its role in heritage preservation

Cultural Intelligence (CQ) refers to an individual’s ability to adapt, communicate, and work effectively in multicultural environments47. CQ is divided into four dimensions: cognitive CQ, metacognitive CQ, motivational CQ, and behavioral CQ48,49. Cognitive CQ refers to understanding the norms, practices, and beliefs across different cultures50, while metacognitive CQ involves an individual’s ability to reflect on cultural knowledge51. Motivational CQ reflects one’s willingness and confidence to adapt to unfamiliar cultural environments52, and behavioral CQ refers to the ability to display flexible behavior in cross-cultural situations51.

In cross-cultural interactions and globalized environments, CQ may influence individuals’ AB. For example, in multinational companies, managers with high CQ tend to be better equipped to understand diverse cultural work habits and communication styles, which can improve their decision-making abilities53,54. Similarly, residents with higher CQ may have a better understanding of the value of cultural heritage, which could lead to more positive attitudes (AB) toward donations52,55.

CQ may be associated with PBC, which could increase individuals’ confidence and adaptability in complex cultural contexts, potentially enhancing their sense of control over DB. This could result in a stronger BI to donate. Additionally, in communities with higher levels of CQ, cultural communication is likely to be more effective, allowing residents to better disseminate donation values, fostering social cohesion and cultural identity. This may strengthen the positive influence of SN on DB22. Therefore, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

H6: CQ is positively related to AB.

H7: CQ is positively related to PBC, thereby potentially enhancing individuals’ BI.

H8: CQ positively moderates the relationship between SN and DB.

The moderating role of intergenerational differences

Intergenerational differences (ID) refer to variations in values, behaviors, and psychological motivations across generations, shaped by distinct socialization backgrounds and historical experiences56,57. Baby Boomers (1946-1964) tend to prioritize stability and loyalty58, Generation X (1965-1980) is more likely to value flexibility and personal growth59, Millennials (1981-1996) are often characterized by their emphasis on work-life balance60, and Generation Z (1997 and beyond) is often defined by reliance on digital technology and instant feedback61.

In cultural heritage preservation, these ID can influence DB by shaping generational attitudes towards cultural responsibility and legacy62. Baby Boomers and Generation X are typically associated with stronger G, driven by long-term social responsibility, while Generation Z, with lower levels of G, tends to prioritize more immediate social effects and personal achievement63. Millennials and Generation Z, having grown up in a multicultural and digital era, are generally associated with higher levels of CQ, which can enhance their AB and DB64.

Millennials are more inclined to engage in projects with international influence and cultural significance65, while Generation Z’s DB appears to be more influenced by peer pressure and social recognition, with a preference for immediate social rewards66. Based on these ID, the study proposes the following hypotheses:

H9: ID moderates the relationship between G and AB.

H10: ID moderates the relationship between CQ and AB.

The mediating role of CQ

Generativity (G), as a motivation to care for future generations and contribute to society, typically drives individuals to engage in positive behaviors21. However, G does not directly influence all Attitudes toward Behavior (AB); instead, it may indirectly affect AB through Cultural Intelligence (CQ). CQ may enhance individuals’ ability to understand and adapt to cultural diversity, potentially enabling their generative concerns to shape more positive attitudes toward Donations Behavior (DB)22,23.

When individuals possess higher CQ, they may be better able to appreciate the diversity and value of cultural heritage, which may lead to more positive attitudes toward DB. This mediating effect suggests that G, through CQ, enhances AB and ultimately influences DB24.

Moreover, CQ plays a key mediating role between G and actual DB. Individuals with strong G typically recognize that donations are an effective way to contribute to society, and CQ helps them navigate cross-cultural complexities, thereby boosting their confidence in turning motivations into actual DB50,52. CQ not only motivates individuals to donate but also helps them convert this motivation into action. This mediating effect highlights CQ’s potential role in supporting the transition from generativity to actual DB67. Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H11: G is indirectly related to AB through CQ.

H12: G is indirectly related to DB through CQ.

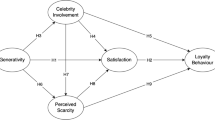

Based on this literature review and these hypotheses, the research model in Fig. 1 was constructed. This model explores the influence of G, CQ, SN, PBC, AB, BI, and ID on cultural heritage donation behavior. It hypothesizes that CQ not only directly affects DB but also moderates the relationship between SN and DB. Additionally, G may indirectly influence AB and DB through CQ, while ID may moderate the effects of G and CQ on AB.

Research areas and methods

Research areas

This study was conducted at three culturally significant sites in Guangzhou, China: the Chen Clan Ancestral Hall, Shamian Island, and Huangpu Ancient Port. These locations were selected for their cultural, historical, and social significance, providing insights into the relationships between G, CQ, and DB across different generations (see Fig. 2).

The selection of these sites was based on several criteria. First, their rich cultural heritage fosters a strong emotional connection with local residents, making them ideal for examining how generativity influences donation behavior. Second, the historical significance of each site provides a backdrop for understanding generational differences in cultural identity and responsibility. Finally, the role of these sites in the local community and tourism sector offers a practical perspective on cross-generational attitudes toward heritage conservation.

Chen Clan Ancestral Hall: Built in 1894, this cultural landmark represents Lingnan architectural art and embodies a strong sense of historical and cultural identity68,69. It is an ideal site for studying the influence of generativity on donation behavior, as residents actively contribute to its conservation for future generations.

Shamian Island: A former foreign concession, this site preserves European-style architecture, reflecting Guangzhou’s history as an international metropolis70. The multicultural environment makes it suitable for examining CQ, as residents’ ability to adapt and understand cultural differences provides crucial insights into cross-cultural dynamics.

Huangpu Ancient Port: As a historic trade hub along the Maritime Silk Road, Huangpu offers a rich commercial and cultural history71. This site is particularly useful for studying generational differences in donation behavior, as its historical significance in global trade highlights the diverse attitudes toward cultural heritage preservation across generations.

These three sites, representing traditional Lingnan culture, multicultural influences, and historical trade heritage, provide diverse data for exploring the impact of generativity and cultural intelligence on donation behavior across generations. The diversity of these research sites enhances the generalizability of the findings, offering valuable empirical support for developing cultural heritage conservation policies.

Questionnaire design and variable measurement

The survey tool was designed based on validated existing scales, with adjustments made to certain items to meet the specific needs of this study. Generativity (G) was measured using the Loyola Generativity Scale (LGS) developed by44. This scale, widely used to assess individuals’ contributions to society and their concern for future generations, has demonstrated high reliability and validity, making it a key tool for measuring generativity.

CQ was measured using the Cultural Intelligence Scale (CQS) developed by50. This scale covers four dimensions: cognitive, metacognitive, motivational, and behavioral CQ, and is widely used in studies on cross-cultural adaptation and understanding. It is known for its strong cross-cultural applicability.

In addition to G and CQ, BI and DB in this study were measured using the TPB framework by31. Following the TPB structure, the questionnaire assessed AB, SN, PBC, BI, and DB. All items were rated using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The specific design for variable measurement is shown in Table 1.

Sample selection

This study employed a stratified random sampling method to ensure that the four generational cohorts—Baby Boomers, Generation X, Millennials, and Generation Z—were adequately represented. Stratification by age allowed the study to specifically examine generational differences in DB, which is a key focus of this research. The sample aimed to gather approximately 300–400 valid responses from each cohort, resulting in a total of 1,463 valid responses across all groups. This distribution ensures that each generational group is well-represented, while also accounting for slight variations in response rates72. In addition to generational stratification, the participant selection process also reflected demographic diversity in terms of gender, education, and income levels. This diversity ensures that the data represent a broad segment of the population, which provides a robust foundation for analyzing the relationships between G, CQ, and DB73.

Data collection

Data were collected through a survey-based approach, using both online and offline channels to ensure broad representativeness and accessibility. A total of 1500 questionnaires were distributed, resulting in 1463 valid responses, yielding a response rate of 97.53%. This high response rate highlights the reliability of the data and minimizes concerns about non-response bias. The online survey was administered through a professional platform using random sampling techniques74, allowing for the inclusion of respondents from various age groups and backgrounds. Anonymity was ensured to encourage honest responses and minimize potential biases such as social desirability75.

Simultaneously, offline surveys were distributed around the study sites in collaboration with site managers and community staff. This approach ensured that part of the sample included residents who were physically present at the research locations, providing further context-specific data. Survey coordinators assisted respondents on-site, ensuring accurate data collection and minimizing any misunderstandings. Before full-scale data collection, a pilot test involving 50 participants was conducted to ensure the clarity and reliability of the questionnaire. Feedback from the pilot test led to minor revisions, enhancing the survey’s effectiveness.

Data analysis methods

The data were analyzed using Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), chosen for its flexibility in accommodating data distribution assumptions and handling complex path models75. PLS-SEM is particularly suited for exploratory research, especially for examining the impact of socio-cultural and psychological factors on behavior, which aligns closely with the objectives of this study76. Additionally, PLS-SEM is popular for its robustness with smaller sample sizes, generating reliable results even when sample sizes are relatively small77. However, this study employed a large sample size (1,463 valid responses), ensuring both the feasibility and robustness of the analysis while further enhancing the reliability of the study’s conclusions. For missing data, as the missing rate was very low, a casewise deletion method was applied, and this approach did not affect the integrity of the final sample78.

Results

Sample demographics

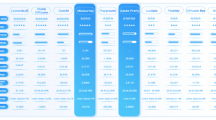

A total of 1463 valid samples were collected in this survey, covering diverse cultural heritage backgrounds, age, gender, education level, income level, and occupation types. Table 2 shows the distribution of the sample across key variables.

The majority of participants came from Huangpu Ancient Port (36.8%), followed by the Chen Clan Ancestral Hall (31.9%) and Shamian Island (31.2%). The gender distribution was nearly equal, with 49.9% male and 50.1% female participants. Most participants were aged between 28 and 43 (40.5%), with the next largest group being those aged 60 or older (23.1%), followed by those aged 44-59 (14.3%). 22.1% were aged 27 or younger. In terms of education, 44.4% had a bachelor’s degree or higher, while 36.3% had a high school diploma or less. Regarding income, 39.2% of participants earned between ¥5,001 and ¥8000 per month, while 11.6% earned under ¥3000 per month. The largest occupational group was employees, making up 58.2% of the sample. These demographics provide a balanced representation of gender, age, and occupation, supporting a solid analysis of G, CQ, and DB.

Descriptive statistics of variables

To validate the proposed model and hypotheses, PLS analysis was performed using standard statistical software. Descriptive statistics were calculated for the key variables, G, CQ, SN, BI, and DB, with mean, skewness, and kurtosis values presented in Table 3.This study focuses on how CQ and G function as key psychological factors influencing DB, as well as exploring their complex interactions through moderation analysis.

The results in Table 3 show that the total scale of this study consists of 35 items. The mean values for the G items range from 3.72 to 3.95, indicating that most respondents expressed a high level of recognition regarding intergenerational responsibility and willingness to contribute to society. The mean values for CQ range from 3.07 to 3.54, reflecting variations in individuals’ ability to adapt to multicultural environments. The mean values for AB, SN, and PBC range from 3.4 to 3.5, suggesting that respondents generally hold positive attitudes toward cultural heritage donations and exhibit strong donation awareness and confidence under social norms. The mean values for BI and DB range from 3.1 to 3.7, indicating that donation intentions and actual behavior are relatively positive, though there is still room for improvement.

Additionally, the skewness values range from −1.083 to 0.063, with absolute values less than 3; the kurtosis values range from −1.088 to 0.681, all below 8. These results demonstrate that the data for these 23 items follow a normal distribution and can be directly used for statistical analyses such as reliability and validity tests79.

Reliability and convergent validity analysis

Reliability analysis is used to assess the internal consistency and stability of the scale. When Cronbach’s α value exceeds 0.7, it indicates a high level of consistency among the items in the scale, reflecting strong reliability80. Convergent validity measures the degree to which different items, when measuring the same latent construct, converge in their results. According to the standards, composite reliability (CR) should exceed 0.7, and the average variance extracted (AVE) should be greater than 0.5 to confirm convergent validity81.

Table 4 shows the reliability and validity indicators for each latent variable. The Cronbach’s α values for all latent variables exceed 0.7, ranging between 0.878 and 0.929, indicating good internal consistency. The CR for each variable exceeds 0.7, and the AVE is greater than 0.5, further confirming the convergent validity of the scale.

To evaluate discriminant validity, this study used the Fornell-Larcker criterion, with results shown in Table 5. The square root of the AVE for each latent variable is higher than its correlation coefficients with other latent variables, indicating good discriminant validity at the construct level.

Additionally, the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) in Table 6 was used to further validate discriminant validity. HTMT assesses the distinction between constructs by comparing the ratio of correlations between traits and within traits82. In this study, the HTMT values for all latent variables are below 0.85, meeting the conservative threshold, which suggests good discriminant validity among the latent variables.

Structural equation modeling results

In the structural equation modeling (SEM) analysis, this study used partial least squares (PLS) to test the hypothesized relationships between the variables. Path coefficients were used to reveal the direction and strength of the influence between latent variables75. To verify the validity of the model and hypotheses, this study utilized SmartPLS 3.2.9 for visualization and employed the Bootstrapping resampling method to calculate the significance of the path coefficients82.

Figure 3 presents the Cultural Generativity Behavioral Model of this study, which includes the path relationships and coefficients between variables such as G, CQ, SN, BI, and DB. This figure visually illustrates the interactions between the variables and their significance levels, further demonstrating the crucial role of CQ as both a moderator and mediator in the model. The specific path coefficients and their significance levels are detailed in Table 7 below.

Table 7 presents the structural equation modeling results, offering insights into the relationships between SN, CQ, G, and DB. Path coefficients, T-values, and P-values were used to evaluate the hypotheses.

H1: AB is positively associated with BI, consistent with the TPB framework, which indicates that attitude is related to forming intentions.

H2: SN is positively associated with BI, indicating that social expectations may influence individuals’ intentions to engage in donation behavior.

H3: PBC is positively associated with BI, highlighting the potential role of self-efficacy in decision-making.

H4: BI is positively associated with DB, aligning with TPB’s suggestion that intention is related to actual behavior.

H5: G is positively associated with AB, suggesting that generativity may be a factor influencing positive attitudes.

H6: CQ is strongly associated with AB, indicating that cultural understanding may contribute to positive attitudes toward donation behavior.

H7: CQ is positively associated with PBC, suggesting that cultural intelligence may help enhance individuals’ confidence in managing donation behaviors.

H8: CQ moderates the relationship between SN and DB, indicating that cultural intelligence may play a role in interpreting social expectations.

H9: No significant association was found between ID and the relationship between G and AB.

H10: ID moderates the relationship between CQ and AB, indicating that intergenerational differences may influence the impact of CQ on attitudes.

H11: CQ mediates the relationship between G and AB, suggesting that cultural intelligence may help translate generative motives into positive attitudes.

H12: CQ also mediates the relationship between G and DB, suggesting that CQ may play a role in converting generativity into actual donation behavior.

Research conclusions and outlook

Discussion

This study used PLS-SEM to examine the influence of CQ and G on DB, exploring their roles as mediators and moderators in the context of the TPB.

Firstly, the study confirmed the influence of AB on BI, which is consistent with the assumptions of the TPB. The individual’s perception of the value of cultural heritage and the personal significance they attach to participating in its preservation significantly affect their donation intentions. In the context of globalization and cultural diversity, cultural identity may shape AB toward DB. Therefore, policymakers should consider developing educational programs and activities that enhance cultural identity and encourage the public to adopt more positive attitudes toward cultural heritage preservation.

Regarding SN and PBC, the study found that they play an important role in shaping donation intentions. This result aligns with previous research by83. PBC, in particular, highlighted how individuals might overcome cultural barriers in cross-cultural contexts and enhance their donation intentions84. The sense of control may significantly encourage individuals to make DB. Therefore, policymakers should consider improving individuals’ sense of control when promoting donation intentions by simplifying donation processes and offering incentives, especially in multicultural settings. Additionally, CQ training, as an effective tool, could help individuals understand and adapt to different cultural views on donations, thereby enhancing their confidence in DB.

The study also confirmed that BI is a strong predictor of actual DB. This finding aligns with the core assumption in the TPB, suggesting that BI influences behavior42. In other words, the stronger the donation intention, the more likely it is that the donation will take place. Therefore, policymakers should focus on strengthening the public’s awareness of cultural heritage preservation and organizing awareness campaigns to indirectly facilitate actual donation behavior.

Regarding generativity, the study highlights the critical role of intergenerational responsibility and social contribution motivation in cultural heritage DB. Generativity motivates individuals to fulfill their sense of intergenerational responsibility through DB, injecting psychological drive into heritage preservation. The findings support the viewpoint of ref. 85, emphasizing the central role of intergenerational responsibility in DB. Generativity is not only an intrinsic motivation driving DB but also reflects societal expectations of individual actions, particularly in the context of public welfare and cultural heritage preservation. Strengthening intergenerational responsibility helps increase donation intentions and enhances the sustainability of DB. Policymakers should pay attention to the influence of generativity by promoting intergenerational education and cultural heritage activities, particularly strengthening intergenerational communication and responsibility transmission at the family and community levels.

The impact of CQ on DB further underscores the importance of CQ in donation decision-making. Individuals with high CQ are better able to understand the diversity and value of cultural heritage, which fosters more positive donation attitudes in cross-cultural contexts. This result aligns with the research of86, showing that CQ not only enhances individuals’ recognition of cultural heritage but also promotes donation intentions by boosting self-efficacy. Therefore, improving CQ helps individuals overcome cultural barriers in the donation process and empowers them to make effective donation decisions. Additionally, CQ enhances individuals’ understanding and adaptability to cross-cultural donation decisions, further improving the sustainability of donation intentions and behaviors.

Lastly, the study also found that CQ significantly moderates the relationship between SN and DB. This indicates that cultural intelligence can enhance the influence of social expectations on individuals’ DB. When individuals possess higher CQ, they are better able to understand and internalize external social norms, making it easier for them to engage in DB. Therefore, in addition to enhancing individuals’ CQ, policymakers should focus on fostering social responsibility for cultural heritage protection through social advocacy and education. Initiatives such as cultural intelligence training programs and cross-cultural learning could further support residents’ engagement in DB.

The study did not support the moderating effect of ID on the relationship between G and AB. This result suggests that cultural heritage DB is more driven by factors such as CQ and donation intentions, rather than the moderating effect of age. In previous studies, older generations often exhibited stronger intergenerational responsibility and higher generativity, which aligns with their motivation for pro-social behaviors87,88. However, in this study, this pattern was not significant, potentially due to several factors.

First, the imbalance in sample sizes across different age groups during data collection may have affected the significance of the results. For example, the 28-43 age group had a significantly higher sample size compared to other groups, and there were also regional differences in sample distribution across specific heritage sites (e.g., Chen Clan Ancestral Hall and Shamian). This imbalance may have limited the statistical power to detect the moderating effect of intergenerational differences.

Second, the study analyzed age as a linear variable, whereas intergenerational differences often exhibit a nonlinear relationship. For instance, different generational groups may display complex layered characteristics in cultural identity and social responsibility. The linear analysis method may not have fully captured these potential nonlinear effects, which may have impacted the significance of the results.

Moreover, in certain cultural contexts, family culture may have mitigated the moderating effect of age on the relationship between generativity and behavioral attitudes. For example, at heritage sites like the Chen Clan Ancestral Hall, family culture may encourage members of the Chen family to be more active in cultural heritage preservation, regardless of their age. This phenomenon suggests that cultural heritage preservation may not only be seen as an intergenerational responsibility but also as an expression of family identity.

Future research should consider adopting more precise measurement methods (such as multi-group analysis or treating age as a categorical variable) and balance the sample distribution across age groups during data collection. Additionally, future studies should incorporate the specific cultural contexts of heritage sites to further explore the complex impact of cultural and intergenerational factors on donation behavior.

The significant moderating effect of ID between CQ and AB suggests that older individuals are more likely to develop more positive donation attitudes through higher CQ. This may be due to their richer cross-cultural experience and deeper cultural understanding, which enables them to recognize the multifaceted value and significance of cultural heritage preservation. Older individuals tend to have more cross-cultural experiences and a deeper understanding of cultural heritage issues, making them more likely to actively engage in donation behaviors. Compared to younger individuals, older individuals can better understand the social and cultural significance of donation behavior through CQ, further enhancing their donation intentions.

CQ, as a mediating variable, amplifies the influence of G on donation attitudes. G drives individuals to focus on intergenerational responsibility and social contribution, while CQ enables this motivation to have a greater impact on AB. Through the mediation of CQ, G is transformed into more specific donation intentions and behaviors. Therefore, DB is not solely driven by emotional or moral responsibility but is also influenced by cultural adaptation and a deeper understanding of multiculturalism. Policymakers should focus on enhancing CQ, enabling residents to better understand and address cross-cultural challenges, thus strengthening their donation intentions.

CQ’s mediating role between G and DB further supports the idea that G not only affects DB through AB but also indirectly promotes the practice of DB through CQ. Research indicates that CQ bridges the gap between cultural heritage preservation and DB, particularly in cross-cultural contexts, where CQ increases individuals’ willingness to donate. This finding offers a new perspective for promoting cultural heritage donations, suggesting that by enhancing CQ, both the volume of donations and the sustainability of DB can be increased.

Theoretical contributions

This study builds upon the traditional TPB and introduces the “Cultural Generativity Behavioral Model,” incorporating two key variables—CQ and (G—into the study of DB. This approach further enriches the existing theoretical framework. The theoretical contributions of this paper are primarily reflected in the following three aspects:

Introduction of CQ as a Core Variable in the TPB Framework: By developing the “Cultural Generativity Behavioral Model,” this study integrates CQ as a central element within the TPB. While traditional TPB models primarily focus on AB, SN, PBC, this study emphasizes the significant role of CQ in a multicultural context. CQ not only influences the relationship between SN and DB but also impacts individual attitudes and donation intentions via G as a motivational factor. This addition brings a new dimension to the TPB, particularly important in today’s globalized, culturally diverse world.

Mediating Role of CQ in Generativity’s Influence on Behavior: CQ is a mediator that influences the relationship between G, AB, and DB. Through this mediation, CQ explains how individuals translate their sense of intergenerational responsibility and social contribution into positive attitudes and donation behaviors. This theoretical contribution sheds light on how psychological motivations, such as generativity, interact with cross-cultural competence, deepening our understanding of how G influences DB. The findings provide a more comprehensive model for understanding prosocial behavior, especially in multicultural settings, and highlight the importance of CQ in the formation of such behaviors.

Moderating Role of ID: The study also highlights the moderating effect of ID between CQ and AB. It shows that older individuals, with their extensive cross-cultural experience, are more likely to be influenced by CQ in forming their attitudes. This contribution expands research on behavior across generations, showing that the moderating role of ID is particularly important in donation behaviors related to cultural heritage preservation. This finding offers theoretical support for future research on donation behavior across generations and helps inform policies aimed at engaging different age groups in heritage conservation.

Practical contributions

The findings of this study provide important practical insights for policymakers and cultural heritage managers. Firstly, the results suggest that enhancing the public’s CQ can significantly boost individuals’ intentions to donate to cultural heritage preservation. Policymakers and managers can promote cultural education programs within schools and communities and organize cross-cultural experience activities to help the public understand and embrace the value of different cultures, thereby improving CQ. Specific measures include organizing exhibitions, lectures, or workshops related to cultural heritage to attract public participation and cultivate cultural sensitivity and identity. These initiatives not only enhance the public’s understanding of cultural diversity but also encourage interaction across generations, laying the foundation for intergenerational cultural transmission.

Furthermore, the policies in Guangzhou aimed at promoting cultural heritage preservation provide a practical framework for encouraging DB. According to the city’s cultural heritage preservation policies, the local government has been committed to protecting and revitalizing historical cultural heritage. As noted in the “Guangzhou Historical and Cultural City Protection and Development Consensus,” the government has strengthened the protection of historical cultural landmarks and revitalized historical neighborhoods and cultural sites through a five-year action plan. For example, Guangzhou has introduced urban renewal and minor renovation projects that retain traditional buildings and cultural heritage while integrating new social functions and cultural elements. This policy strongly supports encouraging residents to participate in cultural heritage preservation and enhances the cultural identity of residents, which could further drive the formation of donation intentions.

To better incentivize donation behaviors, Guangzhou could integrate its existing tax incentive policies by introducing tax deductions or donation reward programs specifically for cultural heritage donations. For instance, establishing a dedicated cultural heritage fund and offering tax benefits or social recognition rewards to donors could effectively encourage both individuals and corporations to participate in donations, supporting the preservation and revitalization of cultural heritage. Moreover, Guangzhou has been focusing on promoting and improving cultural intelligence in recent years by strengthening citizens’ awareness of cultural heritage through cultural education programs and cross-cultural exchange activities. Social events such as Cultural Heritage Day and donor recognition ceremonies could further stimulate residents’ participation in donation activities and cultivate a broader culture of donation.

Lastly, to increase donation participation across different age groups, differentiated incentive strategies should be formulated. For the younger generation, cultural heritage managers could design online interactive platforms or virtual museums to attract them to engage in cultural preservation through innovative methods. Novel forms of participation, such as virtual experiences, social challenges, or online community activities, can inspire their interest and willingness to participate. For older groups, encouraging family participation or intergenerational activities can enhance their willingness to donate. For example, organizing intergenerational cultural programs or Family Cultural Preservation Days not only strengthens family bonds but also helps older individuals feel a stronger sense of social responsibility and cultural legacy in the donation process.

Limitations and future directions

This study has made significant progress in exploring cultural heritage donation behaviors, but several limitations remain. First, the study sample is predominantly concentrated within a specific cultural context, which limits the external validity of the results. As donation behaviors may vary across different cultural contexts, the applicability of the study’s conclusions to other cultural settings remains unclear. Second, the study utilized a cross-sectional design, which only reflects static relationships between variables and fails to reveal the long-term effects of cultural intelligence and generativity on donation behaviors. Consequently, the findings are more applicable to short-term observations and do not capture the dynamic changes in variables over time. Additionally, although the study verifies the mediating role of cultural intelligence and the moderating role of intergenerational differences, the specific mechanisms of these effects were not deeply explored.

Looking ahead, expanding the cultural contexts of the research will enhance the generalizability of the conclusions. Cross-cultural comparisons in future studies could delve deeper into the influence of subjective norms, cultural intelligence, and generativity on donation behaviors across different cultural contexts, thus improving the external validity of the findings. Furthermore, longitudinal designs would help uncover the long-term pathways through which cultural intelligence and generativity influence donation behaviors and capture the dynamic changes in variables at different time points.

Moreover, experimental intervention studies are also worth exploring. By designing cultural education or cross-cultural exchange programs, the impact of cultural intelligence on donation behavior can be verified, providing practical guidance for cultural heritage preservation applications. Finally, future studies can further investigate the specific mechanisms between cultural intelligence and generativity, exploring potential mediators or moderators, such as self-efficacy or social identity, to more comprehensively reveal the psychological and behavioral mechanisms of donation behaviors. By incorporating additional relevant variables such as social capital or trust levels, researchers could gain a more complete understanding of the complexities of donation behaviors and provide new theoretical insights for policy design in the field of cultural heritage preservation.

Conclusion

This study expands the TPB by introducing the “Cultural Generativity Behavioral Model,” highlighting the key roles of cultural intelligence (CQ), generativity (G), subjective norms (SN), and intergenerational differences (ID) in cultural heritage donation behavior (DB). The findings suggest that CQ and G are significant factors influencing DB, with CQ mediating the relationship between G and DB. This underscores the importance of cultural adaptability in enhancing donation behavior, particularly in multicultural settings. Additionally, the influence of subjective norms was found to be weaker in multicultural contexts, while intergenerational differences were found to impact the relationship between CQ and DB.

This research contributes to the theoretical understanding of cultural heritage DB and provides practical insights for policymakers. Specifically, it highlights the value of enhancing CQ and fostering intergenerational responsibility to encourage donation behavior. Policymakers could consider strategies such as CQ training programs and promoting intergenerational education to improve donation intentions and behaviors. Furthermore, this study emphasizes the significance of understanding cultural heritage donation behavior in cross-cultural contexts, especially in today’s globalized and culturally diverse world. Factors like cultural adaptability (CQ) and generational responsibility (G) are closely tied to DB, offering valuable insights for global contexts.

Future studies should further explore the relevance of this model across different cultural contexts, adopting longitudinal and experimental methods to deepen our understanding of the psychological and behavioral factors that influence donation behavior. Additionally, future research could examine how these insights can be applied in various countries and regions, particularly those with significant cultural differences, to test the global applicability and relevance of these findings.

Data availability

The dataset(s) supporting the conclusions of this article is(are) included within the article (and its additional file(s)).

Abbreviations

- AB:

-

Behavioral Attitude

- HTMT:

-

Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio

- AVE:

-

Average Variance Extracted

- ID:

-

Intergenerational Differences

- BI:

-

Behavioral Intention

- PBC:

-

Perceived Behavioral Control

- CQ:

-

Cultural Intelligence

- PLS:

-

Partial Least Squares

- CR:

-

Composite Reliability

- PLS-SEM:

-

Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling

- DB:

-

Donation Behavior

- SEM:

-

Structural Equation Modeling

- G:

-

Generativity

- SN:

-

Subjective Norms

- H:

-

Hypotheses

- TPB:

-

Theory of Planned Behavior

References

Azzopardi, E. et al. What are heritage values? Integrating natural and cultural heritage into environmental valuation. People Nat. 5, 368–383 (2023).

Timothy, D. J. & Boyd, S. W. Tourism and Trails: Cultural, Ecological and Management Issues (Channel View Publications, 2015).

Harrison, R. Heritage: Critical Approaches (Routledge, 2012).

Poria, Y., Biran, A. & Reichel, A. Visitors’ preferences for interpretation at heritage sites. J. Travel Res. 48, 92–105 (2009).

Fatorić, S. & Seekamp, E. Securing the future of cultural heritage by identifying barriers to and strategizing solutions for preservation under changing climate conditions. Sustainability 9, 102 (2017).

Hirsenberger, H., Ranogajec, J., Vucetic, S., Lalic, B. & Gracanin, D. Collaborative projects in cultural heritage conservation–management challenges and risks. J. Cult. Herit. 37, 215–224 (2019).

Jelinčić, D. A. & Šveb, M. Financial sustainability of cultural heritage: a review of crowdfunding in Europe. J. Risk Financial Manag. 14, 101 (2021).

Cheng, E. W. & Ma, S. Y. Heritage conservation through private donation: the case of Dragon Garden in Hong Kong. Int J. Herit. Stud. 15, 511–528 (2009).

Ji, S., Choi, Y., Lee, C. K. & Mjelde, J. W. Comparing willingness-to-pay between residents and non-residents using a contingent valuation method: Case of the Grand Canal in China. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 23, 79–91 (2018).

Tweed, C. & Sutherland, M. Built cultural heritage and sustainable urban development. Landsc. Urban Plan 83, 62–69 (2007).

Lee, J. Y. & Kim, S. S. The effect of multidimensions of trust and donors’ motivation on donation attitudes and intention toward charitable organizations. Nonprofit Manag. Leadersh. 34, 267–291 (2023).

Woosnam, K. M., Aleshinloye, K. D., Strzelecka, M. & Erul, E. The role of place attachment in developing emotional solidarity with residents. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 42, 1058–1066 (2018).

Gannon, M., Rasoolimanesh, S. M. & Taheri, B. Assessing the mediating role of residents’ perceptions toward tourism development. J. Travel Res. 60, 149–171 (2021).

Ganji, S. F. G., Johnson, L. W. & Sadeghian, S. The effect of place image and place attachment on residents’ perceived value and support for tourism development. Curr. Issues Tour. 24, 1304–1318 (2021).

Eslami, S., Khalifah, Z., Mardani, A., Streimikiene, D. & Han, H. Community attachment, tourism impacts, quality of life and residents’ support for sustainable tourism development. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 36, 1061–1079 (2019).

Rey-Perez, J. & Siguencia Ávila, M. E. Historic urban landscape: an approach for sustainable management in Cuenca (Ecuador). J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain Dev. 7, 308–327 (2017).

Dian, A. M. & Abdullah, N. C. Public participation in heritage sites conservation in Malaysia: Issues and challenges. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 101, 248–255 (2013).

Li, H. et al. What promotes residents’ donation behavior for adaptive reuse of cultural heritage projects? An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Sustain Cities Soc. 102, 105213 (2024).

Wang, G., Yao, Y., Ren, L., Zhang, S. & Zhu, M. Examining the role of generativity on tourists’ environmentally responsible behavior: an inter-generational comparison. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 57, 303–314 (2023).

McAdams, D. P., de St Aubin, E. D. & Logan, R. L. Generativity among young, midlife, and older adults. Psychol. Aging 8, 221–230 (1993).

Luo, J. M. & Ren, L. Qualitative analysis of residents’ generativity motivation and behaviour in heritage tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 45, 124–130 (2020).

Frías-Jamilena, D. M., Sabiote-Ortiz, C. M., Martín-Santana, J. D. & Beerli-Palacio, A. Antecedents and consequences of cultural intelligence in tourism. J. Destin Mark. Manag. 8, 350–358 (2018).

Ng, K. Y., Van Dyne, L. & Ang, S. Cultural intelligence: a review, reflections, and recommendations for future research. Group Organ Manag. 37, 24–35 (2012).

Buonincontri, P., Marasco, A. & Ramkissoon, H. Visitors’ experience, place attachment and sustainable behaviour at cultural heritage sites: a conceptual framework. Sustainability 9, 1112 (2017).

Wu, G., Chen, S. & Xu, Y. H. Generativity and inheritance: understanding Generation Z’s intention to participate in cultural heritage tourism. J. Herit. Tour. 18, 465–482 (2023).

Alifuddin, M. & Widodo, W. How is cultural intelligence related to human behavior? J. Intell. 10, 3 (2022).

Pan, Y. & Shang, Z. Linking culture and family travel behaviour from generativity theory perspective: a case of Confucian culture and Chinese family travel behaviour. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 54, 212–220 (2023).

Salinero, Y., Prayag, G., Gómez-Rico, M. & Molina-Collado, A. Generation Z and pro-sustainable tourism behaviors: Internal and external drivers. J Sustain Tour. 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2022.2134400 (2022).

Zaman, U. & Aktan, M. Examining residents’ cultural intelligence, place image and foreign tourist attractiveness: a mediated-moderation model of support for tourism development in Cappadocia (Turkey). J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 46, 393–404 (2021).

McKercher, B. Age or generation? Understanding behaviour differences. Ann. Tour. Res. 103, 103656 (2023).

Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 50, 179–211 (1991).

Godin, G. & Kok, G. The theory of planned behavior: a review of its applications to health-related behaviors. Am. J. Health Promot 11, 87–98 (1996).

Si, H. et al. Application of the theory of planned behavior in environmental science: a comprehensive bibliometric analysis. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health 16, 2788 (2019).

Ulker-Demirel, E. & Ciftci, G. A systematic literature review of the theory of planned behavior in tourism, leisure and hospitality management research. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 43, 209–219 (2020).

Nie, J. et al. Using the theory of planned behavior and the role of social image to understand mobile English learning check-in behavior. Comput Educ. 156, 103942 (2020).

Yuriev, A., Dahmen, M., Paillé, P., Boiral, O. & Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the theory of planned behavior: a scoping review. Resour. Conserv Recycl. 155, 104660 (2020).

Gansser, O. A. & Reich, C. S. Influence of the new ecological paradigm (NEP) and environmental concerns on pro-environmental behavioral intention based on the theory of planned behavior (TPB). J. Clean. Prod. 382, 134629 (2023).

Shen, K. & Shen, H. Chinese traditional village residents’ behavioural intention to support tourism: an extended model of the theory of planned behaviour. Tour. Rev. 76, 439–459 (2021).

Tan, Y., Ying, X., Gao, W., Wang, S. & Liu, Z. Applying an extended theory of planned behavior to predict willingness to pay for green and low-carbon energy transition. J. Clean. Prod. 387, 135893 (2023).

Gonçalves, J., Mateus, R., Silvestre, J. D., Roders, A. P. & Bragança, L. Attitudes matter: measuring the intention-behaviour gap in built heritage conservation. Sustain Cities Soc. 70, 102913 (2021).

Khan, O. et al. Assessing the determinants of intentions and behaviors of organizations towards a circular economy for plastics. Resour. Conserv Recycl 163, 105069 (2020).

Ajzen, I. & Schmidt, P. in The Handbook of Behavior Change (eds. Sniehotta, F. F., Presseau, J. & Araújo-Soares, V.) 17–31 (Cambridge University Press, 2020).

Wiktorowicz, J., Warwas, I., Turek, D. & Kuchciak, I. Does generativity matter? A meta-analysis on individual work outcomes. Eur. J. Ageing 19, 977–995 (2022).

McAdams, D. P. & de St Aubin, E. D. A theory of generativity and its assessment through self-report, behavioral acts, and narrative themes in autobiography. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 62, 1003 (1992).

Urien, B. & Kilbourne, W. Generativity and self‐enhancement values in eco‐friendly behavioral intentions and environmentally responsible consumption behavior. Psychol. Mark. 28, 69–90 (2011).

Wells, V. K., Taheri, B., Gregory-Smith, D. & Manika, D. The role of generativity and attitudes on employees home and workplace water and energy saving behaviours. Tour. Manag. 56, 63–74 (2016).

Wang, K. T. & Goh, M. in The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences: Clinical, Applied, and Cross-Cultural Research (eds. Zeigler-Hill, V. & Shackelford, T. K.) 269-273 (Wiley, 2020).

Ang, S., Van Dyne, L. & Koh, C. Personality correlates of the four-factor model of cultural intelligence. Group Organ Manag. 31, 100–123 (2006).

Ng, K. Y. & Earley, P. C. Culture + intelligence: old constructs, new frontiers. Group Organ Manag. 31, 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601105275251 (2006).

Ang, S. et al. Cultural intelligence: its measurement and effects on cultural judgment and decision making, cultural adaptation and task performance. Manag. Organ Rev. 3, 335–371 (2007).

Ang, S. & Van Dyne, L., editors. Handbook of Cultural Intelligence: Theory, Measurement, and Applications (M.E. Sharpe, 2008).

Bandura, A. Self-efficacy: the Exercise of Control (Freeman, 1997).

Afsar, B., Al-Ghazali, B. M., Cheema, S. & Javed, F. Cultural intelligence and innovative work behavior: the role of work engagement and interpersonal trust. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 24, 1082–1109 (2021).

Presbitero, A. Communication accommodation within global virtual teams: the influence of cultural intelligence and the impact on interpersonal process effectiveness. J. Int Manag. 27, 100809 (2021).

Hofstede, G. Culture and organizations. Int Stud. Manag. Organ 10, 15–41 (1980).

Lyons, S. & Kuron, L. Generational differences in the workplace: a review of the evidence and directions for future research. J Organ. Behav. 35, S139–S157 (2014).

Twenge, J. M., Campbell, S. M., Hoffman, B. J. & Lance, C. E. Generational differences in work values: Leisure and extrinsic values increasing, social and intrinsic values decreasing. J. Manag. 36, 1117–1142 (2010).

Stevanin, S., Palese, A., Bressan, V., Vehviläinen‐Julkunen, K. & Kvist, T. Workplace‐related generational characteristics of nurses: a mixed‐method systematic review. J. Adv. Nurs. 74, 1245–1263 (2018).

Kupperschmidt, B. R. Multigeneration employees: strategies for effective management. Health Care Manag. 19, 65–76 (2000).

Waworuntu, E. C., Kainde, S. J. & Mandagi, D. W. Work-life balance, job satisfaction and performance among millennial and Gen Z employees: a systematic review. Society 10, 286–300 (2022).

Seemiller, C. & Grace, M. Generation Z: educating and engaging the next generation of students. Campus 22, 21–26 (2017).

Oomen, J. & Aroyo, L. Crowdsourcing in the cultural heritage domain: opportunities and challenges. In: Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Communities and Technologies. 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1145/2103354.2103373 (2011).

Schröder, J. M., Merz, E. M., Suanet, B. & Wiepking, P. The social contagion of prosocial behaviour: How neighbourhood blood donations influence individual donation behaviour. Health Place 83, 103072 (2023).

Graça, S. S. Increasing donor’s perceived value from charitable involvement: a multi-segment approach to the American donor market. Int Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 20, 829–852 (2023).

Florenthal, B. & Awad, M. A cross-cultural comparison of millennials’ engagement with and donation to nonprofits: a hybrid U&G and TAM framework. Int Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 18, 629–657 (2021).

Konstantinou, I. & Jones, K. Investigating Gen Z attitudes to charitable giving and donation behaviour: social media, peers and authenticity. J. Philanthr Mark. 27, https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.1764 (2022).

Villar, F. & Serrat, R. in Handbook of Active Ageing and Quality of Life: from Concepts to Applications (ed. Serrat, R.) 121-133 (Springer, 2021).

Cao, M., Wang, P., Wu, L., Lu, Z. & Lu, Q. The research on the online publishing platform of point clouds of Chinese cultural heritage based on LIDAR technology: a case study of Chen Clan Academy in Guangzhou, Guangdong Province. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 452, 1–10 (2018).

Lee, A. K. Fragmented bureaucracies in built heritage conservation: the case of Shamian Island, Guangzhou. Asian Stud. Rev. 40, 600–618 (2016).

Lin, T. & Su, P. Literary and cultural (re)productions of a utopian island: Performative geographies of colonial Shamian, Guangzhou in the latter half of the 19th century. Isl. Stud. J. 17, 28–51 (2022).

Lin, L., Xue, D. & Yu, Y. Reconfiguration of cultural resources for tourism in urban villages—a case study of Huangpu ancient village in Guangzhou. Land 11, 563 (2022).

Cochran, W. G. Sampling Techniques 3rd edn (John Wiley & Sons, 1977).

Groves, R. M. et al. Survey Methodology 2nd edn (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

Groves, R. M. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opin. Q 70, 646–675 (2006).

Hair, J. F., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B. & Chong, A. An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Ind. Manag Data Syst. 117, 442–458 (2017).

Cepeda-Carrión, G., Hair, J. F., Ringle, C. M., Roldán, J. L. & García-Fernández, J. Sports management research using partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM). Int J. Sports Mark. Spons. 23, 284–299 (2022).

Hair, J. F., Risher, J. J., Sarstedt, M. & Ringle, C. M. When to use and how to report the results of PLS-SEM. Eur. Bus. Rev. 31, 2–24 (2019).

Shmueli, G. et al. Predictive model assessment in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for using PLSpredict. Eur. J. Mark. 53, 2322–2347 (2019).

West, S. G., Finch, J. F. & Curran, P. J. in Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications (ed. Hoyle, R. H.) 56–75 (Sage, 1995).

Cronbach, L. J. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika 16, 297–334 (1951).

Fornell, C. & Larcker, D. F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res 18, 39–50 (1981).

Henseler, J., Hubona, G. S. & Ray, P. A. Using PLS path modeling in new technology research: updated guidelines. Ind. Manag Data Syst. 116, 2–20 (2016).

Mittelman, R. & Rojas-Méndez, J. I. Why Canadians give to charity: an extended theory of planned behaviour model. Int Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 15, 189–204 (2018).

Lim, B.-C., Chew, K. Y. & Tay, S. L. Understanding healthcare worker’s intention to donate blood: an application of the theory of planned behaviour. Psychol. Health Med. 27, 1184–1191 (2021).

Malhotra, R. et al. Cultural constructions, motivations, and manifestations of generativity in later life. Innov. Aging 2, 564 (2018).

Yuan, L., Kim, H. J. & Min, H. How cultural intelligence facilitates employee voice in the hospitality industry. Sustainability 15, 8851 (2023).

Nonaka, K. et al. The impact of generativity on maintaining higher-level functional capacity of older adults: a longitudinal study in Japan. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health 20, 6015 (2023).

Moieni, M. et al. Generativity and social well-being in older women: expectations regarding aging matter. J. Gerontol. B: Psychol. Sci. Soc. Sci. 76, 289–294 (2021).

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Macao Polytechnic University under the projects RP/FCHS-02/2022 and RP/FCHS-01/2023.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.C. conceptualized the study, designed the methodology, and wrote the manuscript. H.X. collected and analyzed the data. R.T. conducted data collection and the literature review. J.Y. managed the data and created charts. X.L. guided the introduction and research design. Y.Y. refined the manuscript and provided feedback. H.F. provided funding and contributed to revisions. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, L., Zhang, H., Li, R. et al. How psychological and cultural factors drive donation behavior in cultural heritage preservation: construction of the cultural generativity behavior mode. npj Herit. Sci. 13, 28 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01560-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s40494-025-01560-x

This article is cited by

-

Unpacking digital heritage experiences using PLS SEM and fsQCA through a perception-place behavior model

npj Heritage Science (2026)