Abstract

Cultural memory reflects a group’s emotional attachment, cultural identity, and the social and historical value of intergenerational heritage. Based on the theory of cultural memory, this study classified 783 cultural relics at national and provincial levels in Yuan River Basin of Hunan Province into 8 memory points, 2 memory representations, and 4 memory spaces by type and examined their spatial evolution and hierarchical differences using memory index, kernel density, and field energy model analyses. The results show that the basin’s tangible cultural heritage space has a multi-pole nucleus and multi-cluster structure; traditional villages and intangible cultural heritage resources in the middle reaches are strongly agglomerated, while the upper and lower reaches vary in agglomeration. The work shows how cultural memory aggregates and evolves in geographic space, providing a scientific basis for protecting historical heritage and understanding watershed civilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cultural memory establishes a historical perspective across epochs, illustrates the continuity of human vitality, and elucidates the mechanisms by which human spirituality engages with material space1. Numerous international laws and agreements have been established to underscore the significance of cultural heritage and to furnish a legal framework for its protection. The Venice Charter (1964) establishes an international benchmark for cultural heritage protection, the Convention for the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage (1985) delineates standards and mechanisms for safeguarding world heritage via UNESCO, and the Barcelona Charter (1992) underscores the integration of cultural heritage preservation principles in urban planning. In recent years, the Chinese government has promulgated several policy documents aimed at the protection of cultural heritage, including the enactment of the Intangible Cultural Heritage Law (2011) to preserve intangible cultural heritage related to needlework; the revision of the Cultural Heritage Protection Law (2013) to enhance the safeguarding of local cultural heritage; and the Guidelines for Promoting the Protection and Utilization of Cultural Heritage (2017), which advocate for local governments to develop implementation regulations for cultural heritage protection. Furthermore, the Cultural Heritage Digitization and Protection Project (2011) was initiated to improve the efficacy of preservation and exhibition; funding for cultural protection within the watershed was augmented in the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021); and the Protection and Development Plan for Traditional Villages (NDRC [2021] No. 581) was promulgated to safeguard traditional villages in the watershed. These documents delineate the framework for the rigorous study of cultural assets and offer policy support for the preservation and transmission of watershed culture. This paper examines cultural memory as a focal point, emphasizing the articulation of cultural narratives, rituals, symbols, and other methods of heritage transmission in the Yuan River Basin to augment the vitality of regional culture and the international impact of Yuan River culture.

The historical and cultural heritage of urban and rural areas has garnered significant interest in established cultural memory studies. Urban heritage scholars assert that cities serve as significant sites for the cultivation and evolution of cultural heritage, functioning as unique arenas that amalgamate diverse social structures, ethnicities, and religions2,3. Conversely, rural heritage scholars identify traditional villages, customs, habits, and clan beliefs as vital components of cultural heritage4, providing a crucial foundation for investigating the spatial organization of cultural heritage within micro-regions. Cultural memory research is primarily categorized into two types: one involves utilizing historical materials and ancient maps to delineate the historical evolution of a region influenced by natural and humanistic factors, and to identify key elements for the establishment of a regional heritage pattern4,5,6. The second is to quantitatively delineate and establish the spatial structure and organizational pattern of the current heritage, grounded in the intrinsic value of the heritage and the extent of socio-economic integration7,8. Previous research has highlighted the interplay between tangible and intangible heritage9, illustrated how tangible forms embody intangible practices10, and underscored the significance of intangible elements11. It has also examined natural variables (e.g., hydrology, storms, droughts, etc.)12,13,14 and social variables (e.g., policies, economy)15,16,17, as well as explored representations of cultural memory and evolutionary mechanisms of action. The research methodology employs a conventional participative approach. Traditional research methodologies are predominantly characterized by participatory observation, questionnaire interviews, textual analysis, and geographic field surveys18,19,20,21. In recent years, the advancement of big data and machine learning has prompted scholars to integrate cultural heritage research with imagery22, social media, deep neural networks, and geographic information systems (GIS)23,24 to investigate profound cultural heritage values.

The influence of rivers on human communities is a fundamental subject in the study of watershed civilizations. In determining the scope of watershed studies, researchers concentrate on significant river basins across each continent to investigate their multifaceted cultural, ecological, and socio-economic impacts, including the Amazon River Basin in South America25, the Nile River Basin in Africa26, the Mississippi River Basin in North America27, the Danube River Basin in Europe28,29, and the Yangtze30 and Yellow River31 Basins in Asia, among others. The concept of watershed civilization serves as a nexus between diverse spatial-temporal contexts32 and various elements. Scholars have examined single watersheds through multifactorial33, multidimensional34, and multitemporal lenses35, as well as conducted horizontal comparisons across multiple basins36. Their research emphasizes the elucidation of historical watershed information and the reinforcement of the foundations for the perpetuation of cultural lineages. Research predominantly centers on historical edifices and traditional cultural landscapes, encompassing disciplines such as archaeology, geology, and historical geography. Scholars actively investigate the preservation and development of watershed civilization from diverse viewpoints, proposing innovative concepts such as “Human-water relations”37, “Water culture”38, and “Nature-society” water cycle39. It emphasizes the analysis of the interplay between history and society through the transient and consensus aspects of watershed culture, while concurrently considering national identity, social emotion, and cultural resurrection as the driving forces behind cultural memory study. The research methodology encompasses standard questionnaire interviews40, geographic field surveys41, GIS and cognitive mapping techniques42, and media imagery43.

The Yuan River Basin exemplifies a watershed civilization in southern China, characterized by a significant array of tangible and intangible cultural resources, attributable to its distinctive natural environment and profound historical and cultural legacy. Like the Nile, Mississippi, and Ganges River basins, the Yuan River Basin exemplifies humanity’s capacity to establish civilization within a particular geographic context by adeptly adapting to the natural environment through practices such as terrace farming and water conservancy engineering, alongside the fusion of Central Plains cultures with the ethnic minorities of Southwest China, as well as the preservation and innovation of intangible cultural heritage. The mechanism of cultural memory space generation and the diverse symbiosis of cultural landscapes offer a significant theoretical foundation and practical reference for the study of global watershed civilization, the preservation of cultural diversity, and sustainable development.

Methods

Study area

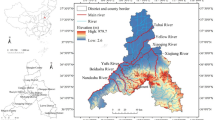

The Yuan River, a significant tributary of the Yangtze River system, originates from Yunwu Mountain in Guizhou Province, traverses Huaihua and Xiangxi Prefecture in Hunan Province, and ultimately converges with Dongting Lake (Fig. 1). It spans approximately 1033 km and encompasses an extensive watershed area, constituting a vital component of China’s southern water system. The Yuan River basin features an abundance of natural resources and a complex, varied topography, exhibiting a geomorphological transition from mountains in the west to hills and subsequently to plains in the east. The Yuan River waterway, originating in the early Spring and Autumn period during the Chu centipede era, constitutes a fundamental segment of the renowned “Ancient Chuanyan Salt Road44”. It has historically served as the primary conduit for military logistics, aquatic transport, and commercial travel, facilitating the most efficient transportation route to and from Yunnan and Guizhou, while also acting as a significant artery for economic and cultural integration. The convenience of waterway transportation facilitated the exchange of resources such as lumber, tung oil, salt, medicinal plants, and coal, hence fostering commercial activities in the region and enhancing the prominence of waterway culture. The proliferation of economic activities facilitated exchanges and interactions among diverse ethnic groups, resulting in the dissemination of songs, dances, folk customs, and practices, which became a significant channel for cultural exchange. As economic exchanges, material distribution, and salt transportation in the basin intensified, coastal communities gradually emerged. The intersection and amalgamation of immigrant culture and ethnic culture illustrate the intricate coexistence of ancient “Wuxi culture”, Chu culture, “barbarian” culture, and the culture of the Ba people in a grand context45. The cultural environment of multi-ethnic settlement groups constitutes a cohesive, unified, and diverse cultural framework.

Objective spatial distribution data

To thoroughly assess the geographical distribution characteristics of cultural assets in the Yuan River Basin, relevant basic information, datasets, and vector data pertaining to tangible cultural heritage, intangible cultural heritage, and traditional villages were gathered and evaluated (Table 1). All data types were meticulously chosen in strict compliance with pertinent national standards and regulations, referencing the official lists provided by national and local authorities, including the State Administration of Cultural Heritage, the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, and the Hunan Provincial People’s Government, as well as the authoritative website of the Computer Network Information Centre of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, to ensure the data’s credibility and scientific validity. The aforementioned data indicates that tangible cultural heritage is primarily utilized to examine the spatial distribution of historical edifices and ancient sites, intangible cultural heritage facilitates the exploration of the transmission and evolution of living cultures, and traditional villages are employed to elucidate the spatial patterns and characteristics of cultural settlements. Simultaneously, the incorporation of vector information offers accurate geographical placement and quantitative backing for the spatial arrangement and environmental description of each sample. The extensive utilization of multi-source data can elucidate the spatial distribution characteristics of cultural assets and its underlying principles in the Yuan River Basin more thoroughly and profoundly.

Subjective interview rating data

To enhance the data’s depth, the researcher employed the Delphi Method, inviting local cultural specialists, historians, heritage protectors, and locals to evaluate the tangible cultural legacy of the Yuan River Basin. Participants were chosen based on the criteria of being scholars or community leaders with a minimum of five years of experience in cultural heritage research or conservation, having resided in the Yuan River basin for an extended duration, and possessing a representative viewpoint in local cultural studies to ensure the inclusion of diverse perspectives. The importance of the heritage was evaluated through three rounds of scoring and feedback, utilizing a standardized 10-point scale. A score of 1 signifies low historical value, while a score of 10 denotes the highest historical value. This approach aims to augment the findings with quantitative data, thereby offering a comprehensive, objective, and comparable analytical foundation for assessing the value of the tangible cultural heritage of the Yuan River Basin.

Cultural memory index

The concept of “mnemonics” was first proposed by Simonides, which laid the foundation for measuring and improving memory ability. Based on the current research on the mechanism of cultural memory and the value of cultural heritage46,47,48,49,50,51, the Cultural Memory Index (CMI) is used to measure the carrying capacity of cultural memory sites in Yuan River Basin in the context of different social forms, culture and art, and religious beliefs52. The following is the calculating formula:

Where: \({{CMI}}_{j}\) is the place \(i\)’s CMI, varying from 0 to 1, and \(i\) is the place’s cultural memory type (the national key cultural relics protection units are utilized as reference items in this study). Two covariates, \({P}_{i}\) and \({{CW}}_{i}\), are often used to calculate the index. With a score threshold ranging from 0 to 10, \({P}_{i}\) stands for the cultural memory space score, which is determined using the Delphi scoring method for six distinct types of cultural memory spaces52. The ratio of the number of memory locations in the defined space types to the total number of cultural memory locations in the Yuan River Basin determines the weight of the cultural memory space or \({{CW}}_{i}\).

Kernel density

The density of the research object in its immediate neighborhood can be measured using kernel density, a non-parametric spatial estimate technique that intuitively captures the spatial aggregation state and distribution pattern of various cultural memory elements. The distribution density of point elements increases with increasing estimated values of kernel density. The following is the calculating formula:

Where \({f}_{n}\left(X\right)\), \(k\), \(h\), \(n\), and \(x-{X}_{i}\) represent the kernel density estimate of culture heritage, kernel function, number of resource points, search bandwidth53, and distance from the resource point to the first resource point, respectively.

Space Field Energy Model (SFEM)

The term ‘field’ originally denotes a physical amount that is dispersed across a space or a portion thereof, so forming a ‘field’. In geography, spatial fields are mostly utilized in urban geography, regional analysis, and various studies, with their application in cultural geography having progressively expanded in recent years54. As a fresh interpretation of the memory location, Nora introduced the idea of the “field of memory”55, which offers an impartial instrument for both qualitatively and quantitatively characterizing alterations in cultural memory. The field’s spatial strength and energy fluctuate dynamically, and its potential energy and memory capacity differ within the boundaries of the cultural memory field. The energy field of cultural memory in this study is the result of the interaction of elements such as cultural heritage, collective memory, and social practice within the Yuan River Basin. It is a reflection of the strength of the distribution, dissemination, and social influence of cultural memory in the basin and can be used to express the magnitude of the radiation force of its culture on the territory by field strength. The Yuan River Basin area is simultaneously influenced by a variety of tangible cultural heritages, and the extent of its comprehensive influence can be demonstrated by borrowing potential energy. The researcher obtained the heritage score data of the study area using the Delphi Method, subsequently calculated the CMI, and subsequently calculated the spatial potential energy and cultural memory field strength. These calculations can quantitatively analyse the field energy characteristics of the cultural memory space56. The following is the formula:

(x, y) represents the coordinates of a certain cultural memory site in spatial dimensions. \(E\) represents the field strength of cultural memory site j; \({{CMI}}_{j}\) signifies the memory capacity of memory site j; \(D\) indicates the distance between memory site j and the administrative quarters within the spatial region (the distance from the cultural preservation site to the county administrative quarters was utilized in the study). \(f\) is the distance friction coefficient, typically assigned a standard value of 2.0. \({EP}\) represents the potential energy of a specific cultural memory region, which constitutes the spatial field energy. j denotes the locus of memory, which pertains to the significance of other locations within the spatial context, and is ascertained by the comparative magnitude of cultural memory.

Bivariate spatial autocorrelation analysis

Bivariate spatial autocorrelation analysis, a fundamental technique in spatial geography, elucidates the synergistic, competitive, or spillover effects of cross-variate spatial relationships by assessing the spatial dependence structure among heterogeneous elements. This study innovatively integrates the concept into the cultural geography research paradigm and establishes a framework for analysing the coupling of heterogeneous cultural elements of ‘traditional villages and non-heritage resources’ within the Yuan River Basin as a spatial unit. The objective is to elucidate the spatial interaction mechanism between two distinct attribute variables at the watershed scale and to illustrate the spatial dependence of traditional villages and their adjacent non-heritage resources in the Yuan River Basin. It demonstrates a positive spatial correlation of high-high and low-low types between the values of traditional villages in the study area and the mean values of neighboring ICH, alongside a negative spatial correlation of low-high and high-low types. The formula for calculation is as follows:

Where: \({X}_{a}^{i}\) and \({X}_{b}^{j}\) represent the values of traditional village density (i) and non-heritage density (j), respectively; \({\bar{X}}_{a}\) and \({\bar{X}}_{b}\) denote the mean values of traditional village density and non-heritage density; \({\delta }_{a}\) and \({\delta }_{b}\) signify the variances of characteristics \(a\) and \(b\); and \({W}_{{ij}}\) is the spatial weight matrix57.

Results

Connotations of spatial representations of cultural memory

Nora’s concept of “lieux de mémoire” posits that particular sites, monuments, or structures serve as focal points for national and cultural memory, facilitating the transmission and preservation of memory58. Tangible cultural legacy, alongside intangible cultural heritage, serves as a medium of cultural memory, forming a distinctive and diverse cultural heritage system that embodies profound social memory and collective identity, while showcasing remarkable historical and artistic accomplishments. Cultural legacy serves as the material foundation of the feeling of place, acting as a significant vessel for collective memory and identity by uniting historical and regional traces, residents’ emotional attachments, and their belief systems and values. Cultural legacy is conveyed through intergenerational transmission and social interaction, manifesting not only in the preservation and recognition of tangible heritage but also in the inheritance and revitalization of intangible cultural assets. This interactive mechanism enables cultural heritage to perpetually reflect and influence societal identity and belonging. Within the framework of globalization and modernization, the mechanism of interaction serves as a crucial element in countering cultural homogenization and preserving the distinctiveness of local culture. The interplay among cultural legacy, sense of place, social memory, and cultural memory might be perceived as a symbiotic mechanism akin to biological systems59 (Fig. 2). Historical and cultural heritage shapes the collective emotions, values, and local attachments of a region, fostering a profound sense of place that serves as a significant manifestation of social memory. The feeling of location is a crucial aspect of social memory and plays an indispensable role in the formation and evolution of cultural memory. The “symbiosis” mechanism is dynamic, continually evolving with historical developments, shifts in social structure, and changes in cultural context. This explains why certain cultural heritages retain their distinctiveness amidst globalization, serving as a foundation for local cultural identity and social cohesion. Consequently, the examination of this “symbiosis” mechanism can elucidate the importance of cultural legacy in contemporary society and offer insights and theoretical backing for its preservation and transmission.

Nora’s ‘memory field’ underscores the symbolic significance of locations in safeguarding collective memory, measuring their spatial influence via cultural memory capacity and administrative distance, so converting symbolic meaning into quantifiable energy gradients. The memory capacity (CMIj) signifies the cultural significance of the site, aligning with Nora’s symbolic memory weights; the administrative distance (D) indicates the physical separation of memory from authority, akin to the reduction of symbolic resonance with distance; and the field strength (E) denotes the spatial impact of each memory site, modeling the symbolic radiative force suggested by Nora. Thus, SFEM converts qualitative theories of memory locations into spatially explicit quantitative expressions.

Construction of cultural memory typology system

Place serves as the fundamental basis and prerequisite for the creation of cultural memory space. We investigate the social and cultural links inherent in the dimensions of place and spatial representation by looking at both the explicit and implicit expressions of material and spiritual memory elements inside the human-land system, so clarifying the laws of cultural evolution and historical lineage supported by different elements. The spatial delineation of cultural memory within the watershed indicates a spatial evolutionary hierarchy focused on the alignment of human-environment interactions, wherein the tacit reproduction of cultural order and the overt execution of agency enhance the cultural and spatial representations of memory shaped by heritage. Heritage serves as a repository for the preservation and revitalization of cultural memory, while the tangible and intangible aspects of the site’s essence offer the necessary medium for depiction60, thereby elucidating the social and existential importance of the space. In conjunction with the cultural memory space classification approach developed, the cultural memory typology in the Yuan River Basin is identified as comprising “8 types of places, 2 types of representations, and 4 types of spaces” (Table 2). The cultural memory space is primarily categorized into four types: spiritual belief, social perception, functional representation, and production and life. This framework encompasses both tangible regional locations and cultural, iconic natural, and humanistic spaces, while also reflecting the sense of place and the dynamics of social action shaped by national beliefs, values, folkways, and customs. (Table 3)

The existing typological framework of cultural memory spaces predominantly adheres to three principal paradigms. The cultural landscape theory (CLT)61 focusses on the notion of feeling of place, analysing the symbolic significances of geography through categories such as religious symbolic landscapes, commemorative landscapes, and daily landscapes. This approach has significant cultural explanatory power but often neglects spatial-functional characteristics and the dynamic aspects of social institutions. The narrative memory school62, based on a binary distinction between archival memory and communicative memory, emphasises the diachronic transmission mechanisms of memory bearers. Nonetheless, it experiences typological simplification and is deficient in a systematic formulation of spatial-topological links. Third, predominant domestic research63, limited by binary epistemologies, employs classification frameworks grounded in material/immaterial and space/time dichotomies, leading to typological units like ritual space and living space, whose boundaries are frequently ambiguous and challenging to operationalize in practice. This paper presents a hierarchical classification framework comprising eight types of memory fields, encompassing two representational dimensions and four types of memory spaces, which builds upon current theoretical underpinnings while achieving three paradigm-level advances. The study identifies eight categories of concrete memory sites—namely NP, SP, and TP—at the typological resolution level, creating a full typological matrix that includes symbolic, functional, and practical components. This detailed classification greatly exceeds the broad categorizations common in previous research. Secondly, regarding the integration of spatial attributes, the framework employs a dialectical relationship between spiritual and material representations, merging the cultural landscape theory’s interpretive tradition of symbolic significance with the socio-spatial theory’s dynamic examination of functional practices. This facilitates a dual explanatory framework that integrates cultural significance and spatial utility. Third, at the level of generative logic and dynamism, the study develops a three-tiered model—memory representations (spiritual/material) – memory field (eight concrete types) – memory spaces (four composite forms)—to systematically elucidate the emergent spatial mechanisms of cultural memory in the collaborative evolution of the mountain–river–human system within the Yuan River Basin. It surpasses the constraints of static classifications in representing the temporal development of cultural space.

Characterization of the temporal sequence of the tangible cultural heritage

The chronological attributes of various dynasties in the Yuan River basin illustrate the intricate interplay between selective transmission, spatial diffusion, and interactions with politics, economy, and ethnicity within cultural memory in a particular historical context. This dynamic process of cultural evolution highlights the unique status and cultural diversity of the Yuan River basin throughout Chinese history. The multi-dimensional analysis of the interplay between cultural characteristics, social systems, and historical factors of historical dynasties and Yuan River culture delineates the historical progression of cultural memory transformation in the Yuan River Basin into eight distinct stages (Figs. 3 and 4):

-

(1)

Prehistoric times. This era’s cultural memory predominantly depends on myths, stories, ancestor veneration, and nascent agricultural civilizations. The historical and cultural heritage is primarily characterized by functional representations (20 items), including ancient ruins and tombs (a in Fig. 4), while ICH is predominantly represented by traditional performing arts and folklore, illustrating the interaction and reliance of the early inhabitants of the Yuan River Basin on nature. The cultural representations depict regional cultural groups, specifically the “river culture group” centered around the middle reaches of the Yuan River in Changde, and the “water culture group” located in the middle reaches of the Yuan River in Xi’an Autonomous Prefecture, indicating that the Yuan River’s suitability for water transportation enhances the spatial mobility of the basin’s cultures.

-

(2)

Pre-Qin dynasty. This developmental phase established a cultural memory focused on military and commerce, characterized by ancient sites that illustrate the nascent stages of agriculture, craftsmanship, and water conservation initiatives, alongside the interactions and amalgamation of the Central Plains cultures and the ethnic minorities of Hunan (b in Fig. 4); the Yuan River emerged as a crucial transportation and military corridor, particularly under the auspices of the “Chu Culture” during the Warring States period. Significantly shaped by the “Chu culture” during the Warring States period, Yuan Shui emerged as a crucial transportation and military corridor, constituting a vital segment of the “Ancient Chuanyan Salt Road”. The Huxi Mountain site group, Zhijiang site group, and Chengtoushan site in the Yuan River exhibit a significant integration of culture, social interaction, and military endeavors, highlighting the distinctiveness of early civilization in the Yuan River basin.

-

(3)

Qin and Han dynasties. This era saw the establishment and strengthening of a centralized state, with the Yuan River becoming included into the national transportation and economic framework, emerging as a vital waterway for transport. Counties were instituted during the Qin Dynasty, and the Han Dynasty enhanced the growth and administration of the Southwest Barbarians, fostering multicultural interactions and the merging of ethnic groups on the frontier, leading to the gradual introduction of Han culture into the Yuan River valley. This developmental phase was characterized by correlative sites (CP), including clan temples and road passes (c in Fig. 4). The Chu tombs, Yuan River city ruins, and ancient roads in the Yuan River basin significantly impacted local funeral customs, illustrating the centralized political structure, emperor worship funeral practices, state rituals and religious convictions, military defense and transportation development, as well as the preservation of knowledge and cultural transmission during the Qin-Han period, thereby encapsulating the fundamental values of power, belief, and culture of that era.

-

(4)

Wei, Jin, and the North-South Dynasties. The influx of numerous immigrants from the north to the south, prompted by political upheaval, transformed the Yuan River basin into a cultural convergence point, leading to the gradual formation of a variegated cultural memory. Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian civilizations coexisted, with cliff stone carvings, Southern Dynasty inscriptions, and celadon and lacquer ceramics illustrating the evolution and persistence of memory forms, characterized by unique regional and ethnic traits, centered around iconic locations (MP) (d in Fig. 4).

-

(5)

Sui, Tang, and Five Dynasties. The escalation of centralization and the proliferation of Buddhism fostered the emergence of socially perceptive categories (four items) of ancient sites, cave temples, and stone sculptures, which serve as emblems of advanced funerary practices, religious ambiance, cultural interchange, and education (e in Fig. 4). Towns near the Yuan River progressively thrived, with cultural recollections centered on transit nodes and economic interactions. The ancient city of Longbiao, representative of the Tang Dynasty, housed relics that encapsulated the political, religious, and economic activities of the era, facilitated the dissemination of diverse cultures, and significantly impacted the formation and perpetuation of cultural identity and historical memory.

-

(6)

Song, Liao, Jin, and Yuan Dynasties. The expansion of the commercial economy and handicrafts further solidified the Yuan River’s status as a significant trading route. The Tusi system implemented during the Yuan Dynasty impacted the political and cultural memory of the Yuan River, while the competition and amalgamation of local ethnic cultures with those of the Central Plains enriched the many qualities of cultural memory elements. Monumental sites (RP) have emerged as the primary medium of memory (f in Fig. 4), exemplified by the Longxing Temple and the remnants of the Old Tea and Horse Trail, which embody profound religious and commercial cultural memories that illustrate the connections and exchanges among diverse ethnic groups.

-

(7)

Ming and Qing Dynasties. The politics of great unification and a thriving trade economy facilitated the secularization and folklorization of memory spaces, advanced the development of the Yuan River basin, expedited shipping and trade activities, and ensured the preservation of notable living spaces (LP) such as the ancient citadel of Fenghuang, the historical architectural complex of Pushi, and the Zhijiang Temple of Literature alongside the Gongcheng Academy of Books (g in Fig. 4). The formation of traditional ancient towns and the accumulation of cultural heritage rendered the cultural memory of this era more intricate, encompassing abundant vestiges of commercial and trade culture, agricultural culture, and the Tusi system.

-

(8)

Modern and contemporary times. In contemporary history, familial and national sentiments significantly influence national destiny and identity. Military sites serve as symbols of collective memory and patriotism, reinforcing national identity while also facilitating reflection on the traumas of war and promoting peace education. The Yuan River Basin served as a significant battlefield and logistical support base during the Anti-Japanese War, exemplifying a prominent category of military-operated cultural space (SP) (h in Fig. 4). This area encompasses various remnants of military infrastructure, including air-raid shelters, trenches, command posts, traces of the Red Army’s Long March, and other facilities, which chronicle military endeavors and the resilience of the populace during that era.

Structural characteristics of the tangible cultural heritage types

Regarding the composition of tangible cultural heritage types (Fig. 5), the quantity of PLMS is the highest at the national level, totaling 44 items, which constitutes 57.1% of the overall national cultural heritage designated for protection in the Yuan River Basin. This underscores the significance of production and life-related cultural memories as essential to the basin’s economy and existence. Consequently, these tangible cultural heritage items have been prioritized for national protection to emphasize their impact. The quantities of SWMS and SPWS items are 16 and 13, respectively, reflecting a wealth of remnants from ethnic cultures, religious beliefs, and traditional ceremonies, particularly in regions populated by ethnic minorities. These items document the history of coexistence and cultural intermingling among diverse ethnic groups, underscoring the profound spiritual and historical importance of the watershed. FCMS possesses the fewest items, comprising 5% or merely 4 items, signifying a scarcity of functional and symbolic memories of tangible cultural heritage that remain inadequately preserved, thereby illustrating that the Yuan River watershed prioritizes production, daily life, and the distinctive tradition of spiritual culture. Regarding provincial heritage objects, SWMS possesses the highest quantity, totaling 166 items, which constitutes 38.9%. This underscores the significance of the spiritual and cultural legacy within the Yuan River Basin, followed by PLMS and FCMS, respectively. There are 61 items of SPMS, representing a mere 14.3%, which signifies a relative deficiency in heritage preservation for cultural identity and perception. The regional variation of tangible cultural material in the Yuan River basin is considerable.

Spatial distribution characteristics of the tangible cultural heritage

Utilizing ArcGIS 10.2 software, the kernel density of various cultural memory types within the Yuan River watershed was calculated. The Standard Deviation Ellipse (SDE) was employed to characterize the distribution attributes of the spatial data, while the natural discontinuity method facilitated visualization and representation (Fig. 6). The SDE is employed to compute the spatial distribution of geographic data points and their diffusion direction, as well as to create an ellipse for visualizing spatial trends and directionality.

-

(1)

The kernel density of SWMS cultural memory space in the Yuan River basin exhibits significant agglomeration in the northwestern region, with the principal core area situated in the western part of Xiangxi. Additionally, dispersed primary core areas are established near the middle and upper reaches, predominantly in locales with pronounced representation of ethnic minority cultures (e.g., Miao-Zhou County of Mayang, Tujia-Miao Autonomous Prefecture of Xiangxi), as well as in mountainous and hilly regions characterized by underdeveloped transportation and rich cultural heritage (e.g., Huitong and Tongdao Counties), as illustrated in Fig. 6. This distribution illustrates the regional nature of cultural memory, indicating that the preservation of cultural heritage is intricately linked to geographic isolation and ethnic cultural transmission. The challenging transportation and somewhat isolated natural environment contribute to the preservation of the profound spiritual heritage, while their regional cultural landscape exhibits significant national cultural identity and distinctiveness.

-

(2)

The kernel density of the SPMS cultural memory space in the Yuan River exhibits a high-density cluster centered around Jishou City, along with two rather autonomous sub-density clusters established by Chenxi and Linli counties (b in Fig. 6). Jishou City, as a high-density cluster, embodies the region’s abundant cultural heritage and diverse ethnic components, whereas Chenxi County and Linli County constitute their own distinct organized agglomerations, indicating a degree of autonomy in the preservation and evolution of their cultural legacies, potentially influenced by particular geographic contexts, social transformations, and local ideologies. The disparities in the accumulation and transmission of cultural memory across regions illustrate the significant impact of local history, national culture, and social structure on cultural identity.

-

(3)

The FCMS cultural memory space illustrates the distribution traits of a high-density cluster centered around Changde City, with Phoenix County serving as a secondary density cluster, both of which generate new agglomerations via the dispersal impact of the core area (c in Fig. 6). This pattern illustrates the spatial attributes of the development of regional history and culture: Changde City, a significant historical and cultural hub, attracts and consolidates numerous cultural memories due to its political, economic, and cultural prominence; Phoenix County, as a sub-center of cultural diversity and ethnic traditions, serves a complementary function in the dissemination of cultural memories. The dispersion of the core component creates a new agglomeration zone, illustrating the dynamic diffusion and restructuring of cultural memory via the core-subcenter model in geographic space.

-

(4)

The PLMS cultural memory space has established multiple gathering points along the Yuan River basin, exhibiting a dual-core structure characterized by significant concentration in the upstream origin area and the core area in the middle reaches (d in Fig. 6), which are interconnected via the Yuan River, thereby forming an organic cultural memory network. Many regions have been transformed into high-density zones, and the linear distribution patterns illustrate the significant impact of waterway transportation on the spatial memory of production and daily life, signifying that rivers serve as both conduits for material flow and vital connections for the transmission of culture and memory. This belt-shaped aggregation pattern emphasizes the linear arrangement of cultural memory in relation to the expansion and distribution along the water system, illustrating the significance of natural geographic features in influencing cultural spatial configuration.

Maps display the spatial density distribution of four types of cultural memory spaces. Kernel values are visualized using a blue-to-red gradient, with red indicating higher density. A unified scale and color ramp are applied across all panels; scale bar = 60 miles. a SWMS: Spiritual Will Memory Space. b SPMS: Social Perception Memory Space. c FCMS: Functional Representation Memory Space. d PLMS: Production-Living Memory Space.

Through the spatial distribution characterization, it was found that SWMS, SPMS, FCMS, and PLMS cultural memory spaces formed different aggregation zones. On the whole, SWMS, SPMS, and FCMS formed a spatial distribution pattern dominated by aggregation zones and supplemented by aggregation belts (a, b, c in Fig. 6), with the existence of certain nucleation density high-value zones but difficult to form effective aggregation zones. On the other hand, PLMS formed a spatial distribution pattern dominated by aggregation zones and supplemented by aggregation areas (d in Fig. 6), with better overall connectivity, forming a smooth cultural memory network.

Energy field pattern of the tangible cultural heritage

The Kriging interpolation technique64 in ArcGIS 10.2 was employed to model the variations in field energy across several cultural memory spaces in the Yuan River basin. The comparative analysis of cross-validation metrics with the Inverse Distance Weighting (IDW) method (Table 4) reveals that both MAE and RMSE are lower than those of IDW, indicating that the Kriging interpolation method more accurately captures spatial structure and diminishes interpolation error. This work employs the Kriging interpolation approach, which leverages the statistical features of geographical data to effectively manage non-uniformly distributed data and yield more precise spatial predictions. Simultaneously, the cultural memory data within the county unit were methodically structured to guarantee the comprehensiveness and representativeness of the data, establishing a foundation for the interpolation analysis.

-

(1)

SWMS and SPMS provide the fundamental conduit for the articulation and dissemination of spiritual and cultural memory. The cognitive and memory processes of human societies exhibit intricate cultural heritage, encompassing military culture, literary works, history, art, and clan beliefs, via heritage socialization. The identification of spiritual cultural memory emphasizes human memory, aiming to objectively examine the material and spiritual elements of the human-earth system, explore the media carriers of cultural memory representation, and clarify the essential principles that regulate the transmission of cultural memory across diverse temporal and spatial contexts. The spatial field energy of the SWMS varied from 2.6723 to 3.2873 (Fig. 7a), whereas the spatial field energy of the SPMS ranged from 0.8878 to 1.1573 (Fig. 7b). Moreover, the spatial field energy of SWMS cultural memory shown considerably larger variability compared to that of material cultural memory representation, suggesting that SWMS is the primary spatial category of spiritual memory content in the Yuan River basin. The SWMS high field energy zones are situated in the central sections of the Yuan River, distinguished by a cross-shaped spatial configuration (Fig. 7a). This structure indicates a robust link to abstract cultural aspects, encompassing inherent spiritual requirements and historical heritage, implying that memory is transmitted by the river and its transportation pathways. In contrast, the high-field energy zones of the SPMS are primarily situated in the middle and lower sections of the Yuan River (Fig. 7b), especially in the border areas with neighboring provinces. This suggests that the border region functions as a spatial nexus for regular cultural exchanges, underscoring the considerable influence of external communication and interaction on the evolution of this sort of cultural memory.

-

(2)

FCMS and PLMS are essential methods for preserving material cultural memory. FCMS culture encapsulates cultural values and social identities through folklore, totemic symbols, ancient sites, and tombs, emphasizing the interaction between material and spiritual dimensions of human existence as the core of memory. In contrast, PLMS cultural memory highlights material heritage closely linked to production activities and everyday life, encompassing agricultural tools, traditional crafts, and residential structures such as historical urban sites and temples, thereby illustrating the unique modes of production and lifestyles of individuals within a specific context. The spatial energy variation of material cultural memory in the Yuan River basin ranges from 0.6113 to 1.3197, reflecting the complexity and spatial diversity of the region’s cultural heritage. The spatial field energy of FCMS cultural memory varied between 0.6113 and 0.8303 (Fig. 7c), which is lower than that of material memory. High energy zones were primarily situated in the central sections of the Yuan River, displaying a gradual spatial gradient over the river’s course, due to the progressive intensification of human activities and the differing developmental timetables of each region. The field energy of PLMS cultural memory varied between 0.9150 and 1.3197, reflecting the intricacy of cultural legacy and its spatial heterogeneity in this location. The PLMS cultural memory spatial field energy varies from 0.9150 to 1.3197 (Fig. 7d), significantly exceeding the field energy scores of the functional characterization type cultural memory. This signifies more robust cultural characteristics and an elevated level of heredity. Regions with heightened field energy are primarily located in the high, middle, and lower sections of the Yuan River, demonstrating that the management of water resources can improve the conservation of local cultural heritage. Water resources, as the essential basis of production and existence, have transformed into a crucial repository of local cultural memory through historical accumulation, promoting agricultural and artisanal advancement, enhancing local culture with deep emotions and resources, and enabling the development of elevated cultural memories along the river.

Maps show modeled spatial field strength for four cultural memory types using a continuous blue-to-red gradient. Higher values correspond to stronger field intensities.All panels apply consistent classification and symbology; scale bar = 60 miles. a SWMS: Spiritual Will Memory Space. b SPMS: Social Perception Memory Space. c FCMS: Functional Representation Memory Space. d PLMS: Production-Living Memory Space.

Structural characteristics of the intangible cultural heritage types

In the Yuan River basin, there are 291 ICH items, comprising 50 at the national level and 241 at the province level, encompassing the ten principal categories of ICH as outlined in ICH National Development [2008] No. 19. Traditional drama prevails among national-level ICHs, comprising 10 items (Fig. 8), which constitutes 20%. This underscores the Yuan River Basin’s rich theatrical heritage, indicating that the flourishing of this domain not only signifies local cultural identity but also highlights the significance of theatrical performances in social life. This is succeeded by traditional music, art, folklore, skills, and dance, with 8 (16%), 7 (14%), 6 (12%), 6 (12%), and 5 (10%) items respectively, indicating the region’s significant engagement in and dissemination of music, arts, and oral traditions. Folkways, traditional medicine, and Chinese Quyi comprised a mere 8%, 4%, and 4% of the total items, respectively, whereas acrobatics were the least represented, with only one item, constituting 2%. This trend illustrates the influence of modernization, restricted living conditions, and developmental constraints on these cultural expressions.

Provincial ICHs exhibit a distinct pattern, with traditional skills comprising the largest category at 63 items, representing 26%. This suggests that the Yuan River basin possesses robust local characteristics and practical foundations in handicrafts and skills, particularly in remote villages and mountainous regions, aligning with the region’s economy, which is primarily agricultural and reliant on traditional crafts. Simultaneously, the increased quantity of folklore and folkways indicates the citizens’ engagement in cultural transmission, with 41 (17%) and 34 (14%) items, respectively. The prevalence of traditional arts, dance, and music was also notable, with 21 (8.7%), 20 (8.3%), and 17 (7%) entries, respectively. Traditional medicine, acrobatics, and traditional drama accounted for relatively modest numbers, at 6%, 5%, and 4%, respectively. The minimum amount of traditional music was merely 9, representing 3.7%. An imbalance in the categories of non-heritage within the Yuan River Basin is evident, necessitating targeted measures for distinct categories of non-heritage items during the conservation and transmission of heritage to ensure the equitable development and preservation of diverse cultural forms.

Spatial distribution characteristics of the intangible cultural heritage

The Yuan River basin is categorized into three regions based on county units, reflecting the characteristics of the river section. The upstream region extends from the source to Qiancheng, encompassing seven counties, including Hongjiang City. The midstream region spans from Qiancheng to Taoyuan Lingjintan, comprising fourteen counties, such as Fenghuang County. The downstream region stretches from below Lingjintan to the outlet of Dongting Lake, including five counties, such as Wuling District. The ArcGIS kernel density measure facilitated the visualization and analysis of the spatial distribution density of traditional villages and ICH. The administrative map of the watershed was segmented into grid-like plots, each measuring 10 km in length and width, which were then superimposed to create a grid decomposition map of traditional villages and ICH (Fig. 9).

-

(1)

The spatial characteristics of traditional villages and intangible cultural heritage in the Yuan River watershed are unevenly dispersed. The distribution of traditional villages exhibits a geographical pattern characterized by clustering in the middle reaches, along with both scattering and clustering in the upstream and downstream regions, displaying distinct regional characteristics. Simultaneously, traditional villages in the middle reaches are predominantly located in Xiangxi county, inhabited by ethnic minorities, whereas the spatial distribution of traditional villages in the upper reaches exhibits minimal variation between the north and south, and the quantity of traditional villages in the lower reaches is significantly limited. ICH predominantly exhibits a spatial distribution characterized by density in the west and sparsity in the east, revealing significant regional imbalances and a strong correlation with traditional communities. From the vantage point of upstream, midstream, and downstream sectors, the distribution of ICH mirrors that of traditional villages: concentrated in the midstream region, dispersed in the upstream, and sparse in the downstream region.

-

(2)

In terms of the number of traditional villages, traditional villages in the upper, middle and lower regions accounted for 31.6%, 68.1% and 0.3% respectively, and in terms of the number of ICH, ICH in the upper, middle and lower regions accounted for 17%, 75% and 8% respectively. Huayuan County possesses the highest number of traditional villages at the county level, with 31, which constitutes 7.8% of the overall count. Longshan County ranked next with 29, while the other counties ranged from 4 to 29, with Taoyuan and Hanshou counties at the lower end with 2 and 1, respectively, and Wuling District in Changde City recording the lowest at 0. Huayuan County possesses the highest number of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH) elements, at 22, which constitutes 8% of the overall count. Yongshun County follows closely with 21 ICH elements. The remaining counties have ICH counts ranging from 3 to 20, while Zhongfang County, with the least at 2, represents 0.7% of the total ICH elements.

Analysis of the association between intangible cultural heritage space and traditional villages

Bivariate spatial autocorrelation models elucidate the relationship between variables and their geographic distribution attributes, discern the aggregation patterns of variables, and are crucial for comprehending the interactions among society, economics, and environment. Consequently, the bivariate spatial autocorrelation model was employed to examine the spatial correlations between conventional village density indicators and ICH density indicators. As can be seen from Fig. 10, the overall “High-High” category in Yuan River watershed is significantly clustered and widely distributed, while the “Low-High” and “Low-Low” categories are scattered and narrowly distributed. (High density of traditional villages - high density of ICH type, referred to as high-high category, the other two categories are traditional village density in the front).

The spatial correlation between traditional village density and intangible cultural heritage (ICH) density in the Yuan River Basin is as follows: The high-high category is primarily located in Yuan River County, Huayuan County, Baojing County, Guzhang County, Yongshun County, and Longshan County. The high distribution density of traditional villages in these regions, coupled with effective preservation efforts, demonstrates a positive spillover effect that perpetuates the safeguarding and transmission of ICH within traditional villages and adjacent areas, thereby establishing a community characterized by interdependence, mutual influence, and synergistic development. The second category is the low-low classification, primarily found in Zhijiang Dong Autonomous County and the downstream region of the Yuan River Basin. The economic infrastructure of Zhijiang Dong Autonomous County is somewhat fragile, with traditional villages and ICH solely dependent on the government’s restricted form of support. Without financial investment and legislative support, traditional villages exhibit inadequate infrastructure, deteriorating conditions, and significant depopulation, resulting in diminished opportunities for the transmission of ICH and weakened sustainability. Traditional villages in the downstream region of the Yuan River basin are less numerous, less densely populated, and exhibit superior economic development. Due to the influence of foreign culture and the modern economy, they are progressively losing the essence of intangible cultural assets, including traditional handicrafts and folk activities, making it challenging to transmit and conserve this cultural legacy. Thirdly, the low-high category, exemplified by Jishou City, denotes a low-value regional unit encircled by high-value regions. Although Jishou City is situated in an urban area with a sparse density of traditional villages, its ICH is preserved more comprehensively and in greater quantities. This preservation is attributed to its diverse ethnic cultures and folklore traditions, as well as policy support, financial investments, and the advancement of the tourism sector, which have facilitated the demonstration and transmission of the ICH. The remaining counties are all insignificant regions, indicating that multi-point scattered agglomeration is the primary distribution characteristic of the Yuan River basin.

Bivariate spatial autocorrelation assesses the potential spatial dependence and correlation of an attribute, whereas the global Moran’s I calculation primarily elucidates the spatial disparities and overall correlation of cultural memory. A Moran’s I value greater than 0 signifies spatial similarity in high or low value areas of traditional villages and ICHs, while a value less than 0 indicates significant spatial dissimilarity65. The Moran’s I index depicted in Fig. 11 demonstrates a substantial and statistically significant value of 0.473, exceeding zero, which signifies a pronounced spatial positive correlation between the density of traditional villages and the density of ICH across various counties and districts, thereby indicating evident spatial agglomeration within the Yuan River basin.

Discussion

Cultural heritage, as the material manifestation of Yuan River civilization during a specific historical epoch, results from the multifaceted influences of nature and society, as well as material and spiritual elements within the Yuan River Basin. It serves as a significant cultural form within the cultural framework of the Yuan River Basin, authentically representing collective cognition, emotional bonds, spiritual values, historical traditions, and folk customs. Additionally, it functions as a medium for collective memory, embodying both the transient and the shared consensus of the community. The eight classifications of cultural memory locations highlighted in the study underscore the pivotal role of cultural memory in social identity, establish a theoretical foundation for the preservation and advancement of national culture, and expand the domain of cultural heritage research. The spatial distribution of tangible and intangible cultural legacy illustrates the dynamic interplay between human actions and cultural cognition, so enriching the comprehension of cultural memory theory. The findings offer empirical evidence for the preservation of cultural assets and the advancement of minority cultures in the Yuan River basin, assisting policymakers in the successful planning and execution of conservation measures to maintain regional cultural attributes. These findings may redefine the trajectory of cultural research, foster interdisciplinary collaboration among cultural geography, historical anthropology, and sociology, and offer novel insights into the processes of constructing and transmitting cultural memory.

This study systematically examines the value orientation of cultural heritage preservation and historical-cultural transmission in the Yuan River Basin, utilizing the group cultural identity framework of heritage representation within the geographical confines of the Yuan River Basin, as influenced by the evolution of the human-land relationship. In comparison to prior studies, various fundamental values and innovations are evident in the following dimensions. Initially, at the content level, we connect national culture with basin culture, delineate the process of cultural memory construction in the Yuan River basin from the standpoint of heritage representation, pinpoint the cognitive deficiencies in the relationship between cultural memory and heritage in contemporary research, and offer significant relational support for investigating the value revitalization of cultural heritage and its preservation pathways. Secondly, at the methodological level, a spatial field energy model of the CMI has been developed and integrated with kernel density analysis and a bivariate autocorrelation model to create a more comprehensive system of spatial analytic methods. Compared with the traditional spatial kernel density that only focuses on point elements, the field energy model quantifies the spatial radiation range and influence intensity of cultural memory elements, breaks through the limitation of kernel density analysis on point elements, and expands the processing scope to face and line cultural elements, which can reflect the spatial influence of cultural memory elements more comprehensively. The research technique employed in this paper provides an analytical reference for the theoretical research connected to cultural memory and heritage, as well as an application means for the systematic protection of cultural assets in Yuan River Basin. The perspective level, which integrates the spatial characterization of cultural memory related to tangible cultural heritage, traditional villages, and intangible cultural heritage, offers a novel viewpoint for enhancing and advancing cultural memory theory and cultural heritage protection theory, while also serving as a reference for contemporary research on the spatial structuring of cultural memory.

The examination of cultural heritage within the framework of globalization has progressively expanded beyond mere tangible legacy preservation to emphasize its multidimensional, dynamic, and trans-geographical effects. Under UNESCO’s promotion, cultural heritage is increasingly recognized as a transnational and cross-cultural collective asset. The process of spatial identification and the construction of cultural memory regarding cultural heritage in the Yuan River Basin illustrates the preservation and transformation of local cultural memory within the framework of globalization, indicating that local culture is interconnected and aligns with the ‘global-local’ dialectic. In the formation of group cultural identity, heritage transcends mere historical documentation and becomes an active social activity. This study reveals the connection between places of cultural memory and group identity in the Yuan River basin, and through the identification of eight places of cultural memory, it explores how tangible and intangible cultural heritage forms collective memory through space and practice, and maintains uniqueness in the maintenance of local culture and the regeneration of global cultural identity.

Based on the perspective of historical and cultural heritage and the theory of cultural memory, the study explores the characteristics of cultural memory in Yuan River Basin under the perspective of heritage conservation, summarizes the spatial logic and the order of classification of types, and discusses the changing characteristics, spatial texture and spatial distribution of non-representational places of different types of cultural memory in the space of Yuan River Basin, and the main conclusions are as follows: (1) The type system of cultural memory space in Yuan River Basin is clarified. The cultural memory and spatial types in Yuan River basin are mainly divided into 2 types of memory representations of culture and space, 8 types of cultural memory places such as strategy and text place, and 4 types of cultural memory and spatial types such as spiritual will memory space, social perception memory space, functional representation memory space, production-living memory space. (2) The distinct pattern and hierarchy attributes of material cultural heritage representations in the Yuan River Basin are elucidated. The distribution and evolution of cultural memory space in the Yuan River Basin reveal that the material memory space exhibits a spatial structure characterized by multiple nuclei and groups, demonstrating significant agglomeration traits; conversely, the spiritual memory space is less varied, displaying multi-centric development and a relatively stable structural framework. The geographical domain of cultural memory exhibits distinct variations in elevation, characterized by a clear hierarchical structure. (3) The spatial distribution of intangible cultural heritage representation sites in the Yuan River Basin exhibited positive agglomeration. Traditional villages and intangible cultural heritage (ICH) exhibit a close spatial correlation, with their collective memory space demonstrating significant positive autocorrelation characteristics. Spatial agglomeration is pronounced as strong in the middle reaches of the river, moderate in the upper reaches, and weak in the lower reaches.

Certain insights into the continuation of the Yuan River Basin’s cultural memory in terms of cultural memory protection and the cooperative use of heritage space in practice can be gained from the multifaceted response of tangible and intangible cultural heritage in geographic space, as well as the requirements of China’s “14th Five-Year Plan” cultural development plan and rural revitalization strategy: Firstly, to execute sustainable cultural tourist development, utilize the core cultural legacy of the Yuan River basin as a foundation, extend to adjacent distinctive cultural nodes, and establish a multi-tiered, multi-scalar, and multi-centric spatial network system of cultural memory. Utilizing the planning idea of ‘heritage+tourism+nostalgia’, we will advance the high-quality and profound integration of local culture and tourism, thereby enhancing collective identity and cultural confidence. Secondly, to implement a four-tiered dynamic monitoring and evaluation framework (national, provincial, municipal, and county levels), establish a dynamic monitoring system for cultural memory spaces, routinely assess the efficacy of protective measures, promptly modify and enhance management strategies, and create a closed-loop management system of ongoing improvement through social feedback, academic inquiry, and policy assessment, thereby adapting to the continually evolving social and cultural landscape. Thirdly, to advance the living transmission of cultural heritage, leverage the clustering attributes of the memory space, and spearhead the establishment of a memory emblem for the Yuan River Basin, including the design of a cohesive visual identity system and the development of a series of cultural intellectual properties and derivatives. Furthermore, enhance the interconnection with the cultural and creative sectors to facilitate the profound integration of cultural preservation and innovation.

The work offers comprehensive insights but lacks interdisciplinary ideas on collective memory, customary memory, mnemonics, and public memory, and does not thoroughly explore the dialectical link between individual and collective memory. In the discourse regarding the relationship between civilization and heritage in the basin, there is an insufficiency of depth in examining whether heritage construction pertains to the individual or the collective, as well as a deficiency in systematic analysis of the interactive mechanism between individual narratives and collective identity. The cultural heritage diversity in the Yuan River basin’s ethnic regions renders the analysis of historical connotations somewhat inadequate, and there is a deficiency in thorough examinations of the variances in cultural memories and their interactions among distinct ethnic groups and regions within the basin, resulting in an incomplete representation of their cultural memories. While the spatial field energy model aids in comprehending the general progression of cultural memory in the basin, a more profound analysis of social events and local customs during specific time periods requires enhancement.

In light of the research limitations, future efforts should focus on the exact delineation of the cultural heritage of watershed civilizations and ethnic regions, particularly regarding the principal entities involved in heritage construction. Additionally, there should be an enhancement of comparative analyses between various watershed cultures within China and those of representative watershed cultures worldwide, facilitating more profound theoretical discourse. For instance, the various modes of multicultural coexistence and the persistence of a singular civilization in the Yangtze River Basin and the Nile River Basin; the pronounced disparity between the origins of civilization and the dynamics of multiculturalism in the Yellow River Basin and the Mississippi River Basin; and the distinctions in the diversity and interactions of ethnic cultures within the cross-border Lancang-Mekong River Basin. Future research ought to leverage worldwide experiences, explore the distinctive worth of Chinese river basin culture, and develop a theoretical framework for cultural heritage preservation that embodies Chinese traits. Furthermore, comprehensive analyses of the historical implications of various forms of cultural heritage should be enhanced to effectively illustrate the diversity and intricacy of cultural memory; additionally, spatial analysis techniques should be further investigated to uncover social phenomena and historical trends within a specific temporal context at a more profound level.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Bollinger, E. Cultures and literatures in dialogue: the narrative construction of Russian cultural memory (Taylor and Francis, 2022).

Zeayter, H. & Mansour, A. M. H. Heritage conservation ideologies analysis–Historic urban landscape approach for a Mediterranean historic city case study. HBRC J.14, 345–356 (2018).

Coombes, M. A. & Viles, H. A. Integrating nature-based solutions and the conservation of urban built heritage: challenges, opportunities, and prospects. Urban For. Urban Greening 63, 127192 (2021).

Dragan, A., Ispas, T. R. & Crețan, R. Recent urban-to-rural migration and its impact on the heritage of depopulated rural areas in Southern Transylvania. Heritage 7, 4282–4299 (2024).

Luo, D. Analysis of successful cases based on rural heritage conservation and community participation. Acad. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 7, 76–92 (2024).

Zhang, J. H. et al. Analysis of the evolution pattern and regional conservation of cultural heritage from the perspective of urban sustainable transformation: the case of Xiamen, China. Buildings 14, 565 (2024).

Li, H., Zhang, T., Cao, X. S. & Yao, L. L. Active utilization of linear cultural heritage based on regional ecological security pattern along the straight road (Zhidao) of the Qin Dynasty in Shanxi Province. China. Land 12, 1361 (2023).

García, E. J. A. & Altaba, P. Identifying habitation patterns in world heritage areas through social media and open datasets. Urban Geogr. 44, 2280–2292 (2023).

Laura, V. & Sam, G. The spatial morphology of community in Chipping Barnet c.1800–2015: an historical dialogue of tangible and intangible heritages. Heritage 4, 1119–1140 (2021).

Apaydin V. Critical perspectives on cultural memory and heritage: Construction, transformation and destruction. UCL Press. https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787354845 (2020).

Deacon, J. H. Conceptualising intangible heritage in urban environments: challenges for implementing the HUL recommendation. Built Heritage 2, 72–81 (2018).

Sesana, E., Gagnon, A. S., Ciantelli, C., Cassar, J. & Hughes, J. J. Climate change impacts on cultural heritage: a literature review. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Climate Change 12, e710 (2021).

Lombardo, L., Tanyas, H. & Nicu, I. C. Spatial modeling of multi-hazard threat to cultural heritage sites. Eng. Geol. 277, 105776 (2020).

Bonazza, A. et al. Safeguarding cultural heritage from climate change related hydrometeorological hazards in Central Europe. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduction 63, 102455 (2021).

Gillian, F. & Ruba, S. The circular city and adaptive reuse of cultural heritage index: measuring the investment opportunity in Europe. Resour. Conserv.Recycl. 175, 105880 (2021).

Lak, A., Gheitasi, M. & Timothy, D. J. Urban regeneration through heritage tourism: cultural policies and strategic management. J. Tour. Cult. Change 18, 386–403 (2020).

Kristine, K., Janne, I., Colette, O., Wolfgang, H. & Ingrid, K. Cultural heritage, sustainable development, and climate policy: comparing the UNESCO World heritage cities of Potsdam and Bern. Sustainability 13, 9131–9131 (2021).

Pascarianto, B. & Tetsuya, A. Evaluation of the Orobua settlement as a historical heritage in West Sulawesi, Indonesia. J. Asian Archit. Building Eng. 22, 1582–1597 (2023).

Li, W., Jiao, J. P., Qi, J. W. & Ma, Y. Q. The spatial and temporal differentiation characteristics of cultural heritage in the Yellow River Basin. PloS ONE 17, e0268921 (2022).

Lu, Y. & Ahmad, Y. Heritage protection perspective of sustainable development of traditional villages in Guangxi, China. Sustainability 15, 3387 (2023).

Huang, Y. & Yang, S. D. Spatio-temporal evolution and distribution of cultural heritage sites along the Suzhou canal of China. Heritage Sci. 11, 188 (2023).

Mishra, M. Machine learning techniques for structural health monitoring of heritage buildings: a state-of-the-art review and case studies. J. Cult. Herit. 47, 227–245 (2021).

Condorelli, F., Rinaudo, F., Salvadore, F. & Tagliaventi, S. A neural networks approach to detecting lost heritage in historical video. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inform. 9, 297 (2020).

Li, X. B. et al. Research on the construction of intangible cultural heritage corridors in the Yellow River Basin based on GIS and MCR model. Herit. Sci. 12, 271 (2024).

Maldonado-Erazo, C. P., Tierra-Tierra, N. P., del Río-Rama, M. D. L. C. & Álvarez-García, J. Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage: the Amazonian Kichwa people. Land 10, 1395 (2021).

Yohannes, H., Soromessa, T., Argaw, M. & Dewan, A. Spatio-temporal changes in habitat quality and linkage with landscape characteristics in the Beressa watershed, Blue Nile Basin of Ethiopian highlands. J. Environ. Manag. 281, 111885 (2020).

Meyer, H. Toward a cultural heritage of adaptation: a plea to embrace the heritage of a culture of risk, vulnerability and adaptation. in Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage. Springer, Cham. 401 (2020).

Hristić, N. D., Stefanović, N. & Milijić, S. Danube river cruises as a strategy for representing historical heritage and developing cultural tourism in Serbia. Sustainability 12, 10297 (2020).

Sommerwerk, N. et al. The Danube River Basin. in Rivers of Europe (Elsevier, 2022).

Chen, W. X. et al. Spatio-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages in the Yangtze River Basin: a Geodetector model. Herit. Science 11, 111 (2023).

Feng, Y. et al. Spatiotemporal evolution characteristics and influencing factors of traditional villages: the Yellow River Basin in Henan Province, China. Heritage Sci. 11, 97 (2023).

(in Chinese) Wang, F. et al. River basin civilization and high-quality development of its livable urban and rural areas. Geogr. Res. 42, 895-916 (2023).

Li, X. Q. et al. Geographical distribution and influencing factors of intangible cultural heritage in the three Gorges reservoir area. Sustainability 15, 3025 (2023).

Angrisano, M., Nocca, F. & Santolo, D. S. A. Multidimensional evaluation framework for assessing cultural heritage adaptive reuse projects: the case of the seminary in Sant’Agata de’ Goti (Italy). Urban Sci. 8, 50 (2024).

Zaina, F. & Nabati Mazloumi, Y. A multi-temporal satellite-based risk analysis of archaeological sites in Qazvin plain (Iran). Archaeol. Prospect. 28, 467–483 (2021).

Nie, Z. Y., Dong, T. & Pan, W. Spatial differentiation and geographical similarity of traditional villages—Take the Yellow River Basin and the Yangtze River Basin as examples.Plos ONE 19, e0295854 (2024).

Wu, B. H., Quan, Q., Yang, S. & Dong, Y. X. A social-ecological coupling model for evaluating the human-water relationship in basins within the Budyko framework. J. Hydrol. 619, 129361 (2023).

Benarroch, A., Rodríguez-Serrano, M. & Ramírez-Segado, A. New water culture versus the traditional design and validation of a questionnaire to discriminate between both. Sustainability 13, 2174 (2021).

Ma, Z., Xie, W. W., Ma, W. J., Su, S. J. & Niu, X. X. The ternary water cycle of ‘Nature–Society–Trade’ in the inland arid areas. Hydrol. Process. 38, e15133 (2024).

Sardaro, R., La Sala, P., De Pascale, G. & Faccilongo, N. The conservation of cultural heritage in rural areas: stakeholder preferences regarding historical rural buildings in Apulia, Southern Italy. Land Use Policy 109, 105662 (2021).

Sánchez, M. L., Cabrera, A. T. & Del Pulgar, M. L. G. Guidelines from the heritage field for the integration of landscape and heritage planning: a systematic literature review. Landsc. Urban Plann204, 103931 (2020).

Pepe, M., Costantino, D., Alfio, V. S., Restuccia, A. G. & Papalino, N. M. Scan to BIM for the digital management and representation in 3D GIS environment of cultural heritage site. J Cult Herit50, 115–125 (2021).

Alshawabkeh, Y., Baik, A. & Miky, Y. Integration of laser scanner and photogrammetry for heritage BIM enhancement. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inform. 10, 316 (2021).

Zhao, S. W. et al. The spatio-temporal characteristics and influencing factors of settlement name cultural landscape from the perspective of ancient waterway: take the Yuanshui River Basin in Hunan as an example. Geogr. Res. 43, 214–235 (2024).

Zhao, W. Q., Xiao, D. W., Li, J., Xu, Z. Y. & Tao, J. Research on traditional village spatial differentiation from the perspective of cultural routes: a case study of 338 villages in the Miao frontier corridor. Sustainability 16, 5298 (2024).

Apaydin, V. The interlinkage of cultural memory, heritage and discourses of construction, transformation and destruction. Critic. Perspect. Cult. Memory Herit 1, 13–30 (2020).

Hallam, E. & Hockey, J. Death, memory and material culture. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003085164 (Routledge, 2020).

Zhang, S. N., Ruan, W. Q. & Yang, T. T. National identity construction in cultural and creative tourism: The double mediators of implicit cultural memory and explicit cultural learning. Sage Open 11, 21582440211040789 (2021).

Whitehead, C., Eckersley, S., Daugbjerb, M. & Bozuglu, G. Dimensions of heritage and memory. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781138589476 (Routledge, 2021).

Wu, Z. C., Ma, J. & Zhang, H. Q. Spatial reconstruction and cultural practice of linear cultural heritage: a case study of Meiguan historical trail, Guangdong, China. Buildings 13, 105 (2023).

Qi, J. W., Li, W., Zhang, K. & Wang, L. C. Cultural memory construction and spatial identification in Yellow River Basin from the perspective of heritage representation. J. Arid Land Resour. Environ. 38, 75–86 (2024).

Linstone, H. A., Murray, T. E. The Delphi method. Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, 1975.

Heidenreich, N. B., Schindler, A. & Sperlich, S. Bandwidth selection for kernel density estimation: a review of fully automatic selectors. AStA Adv. Stat. Anal. 97, 403–433 (2013).

Anderson, B. Cultural geography II: The force of representations. Progress Human Geogr. 43, 1120–1132 (2019).

Węglarczyk, S. Kernel density estimation and its application. ITM web of Conf. 23, 00037 (2018).

Remizova, O. Architectural memory and forms of its existence. J. Archit. Urban. 44, 97–108 (2020).