Abstract

Proximal Sound Printing (PSP) is a new class of additive manufacturing (AM) processes where on-demand polymerization occurs through ultrasound waves interacting with printing material right at the proximity of the acoustic aperture by inducing cavitation. Despite recent developments in sound-based AM techniques, inherent practical limitations still remain, such as low resolution and repeatability, as well as the inability to print multi-material structures. PSP overcomes these limitations, enhancing resolution tenfold, reducing printing power fourfold, and decreasing maximum acoustic streaming velocity 1600 times compared to common sound-based printing methods, enhancing repeatability and resolution. PSP offers greater versatility than existing methods in modulating feature size through printing aperture tuning. This capability is particularly valuable for fabricating microsystems, where high-resolution patterning and material integrity are essential. Furthermore, PSP enables the direct printing of heat-curing materials such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), a widely used thermoset in microfluidics and soft lithography, without altering its native formulation. The PSP process is explored through sonochemiluminescence experiments and high-speed imaging and demonstrated by the successful printing of multi-material composite structures and functional microfluidic devices. Overall, PSP establishes a practical, high-resolution approach for sound-driven additive manufacturing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Microsystems such as microfluidic devices, sensors, and lab-on-a-chip platforms have become essential tools in biomedical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and chemical analysis, enabling precise manipulation of fluids and particles at the microscale1. Additive manufacturing (AM) offers promising pathways for rapid prototyping and enhanced design flexibility in microsystem fabrication, potentially overcoming the limitations of conventional techniques such as soft lithography and etching2.

Among the materials used in microsystems, polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) is a widely used thermoset due to its biocompatibility, optical transparency, and flexibility3. Its widespread use in research and commercial microdevices has motivated efforts to 3D print PDMS directly. However, PDMS is a thermoset polymer, and the additive manufacturing of thermosets, including PDMS and epoxies, poses significant challenges, particularly with heat- and light-based curing methods4.

Additive manufacturing of thermosets such as epoxy or silicone-based polymers has witnessed significant advancements in utilizing various energy sources to fabricate intricate structures5,6,7,8 and multifunctional materials9,10,11,12. Light and heat are dominant energy sources that drive chemical reactivity in the 3D printing of thermosets. Photocuring-based AM methods, such as digital light processing (DLP)13,14,15 and stereolithography (SLA)16,17,18, are limited to photo-curable resins, which also restrict the versatility of these methods due to challenges like light attenuation and material customization19. Printing heat-curing thermosets by incorporating a heat source is limited to approaches that utilize supporting medium20,21,22,23, frontal polymerization24,25, or rheological modification26,27,28,29. Supporting medium/bath 3D printing methods usually result in weak structures, limited multifunctional material possibilities, and a high post-processing procedure to remove the supportive medium23. The frontal polymerization approach is limited to high exothermic materials to provide the required energy density for in situ gelation at the vicinity of the nozzle head24,26. In rheological modification approaches, the viscosity of the printing material is tuned by an additive, which changes the material property of the final printed part27. In a recent approach to in-situ dual heating, a heat curing process by a Joule heater integrated into the direct ink writing (DIW) system is proposed to facilitate the curing of thermosets26. This method is constrained by the small size of the extruding nozzle (25 µm~1 mm) to deposit the printing material with controlled viscosity, resulting in a slow printing process. Control over the heat transfer, along with the complexity of the mechanism concerning head size and the need for auxiliary cooling systems, poses further limitations. Fast polymerization of thermosets through plasmonic effects achieved by incorporating gold nanoparticles30 demonstrated the potential to enhance the curing rate and enable on-demand curing. However, the practical application of the incorporation of gold nanoparticles in AM remains unproven. Furthermore, gold is a costly material, and its extraction post-printing has proven to be a challenging process31.

In addition to light and heat-based AM methods, recently, our research group has introduced a new class of AM processes called Direct Sound Printing (DSP), based on using sound waves to drive on-demand polymerization32,33,34 in which the sonochemical reactions35,36,37,38,39,40 are driven by a focused ultrasound source to 3D print objects from heat-curing thermosets. DSP offers distinctive advantages over light and heat-based methods, including the use of commercially available heat-curing resins for printing without any viscosity modification, having homogeneous mechanical properties of the fabricated parts, absence of any toxic byproducts32 due to its environmentally friendly process41,42 and rapid post-processing time in the order of minutes32.

Pioneering sound-based AM processes32,33,34 have captured the attention of researchers, sparking new investigations in 3D printing utilizing ultrasound and paving the way for exciting advancements in bioprinting, introducing the possibility of printing beyond physical obstacles, such as inside the human body. The idea of non-invasive deep printing inside the body and its integration with an imaging system, such as ultrasound, along with an ex-vivo proof of concept was introduced in our early proof of concept demonstration32. The chemical reactivity induced by ultrasound sources arises from a combination of thermochemistry, caused by heat generated through acoustic attenuation, and sonochemistry, driven by the formation and collapse of acoustic cavitation bubbles. The temperature increase at a macroscopic scale of the focal region due to acoustic attenuation was not sufficient to drive the on-demand curing through thermochemistry in silicone elastomers or epoxies; therefore, sonochemical reactions in the acoustic cavitation bubbles are proposed for on-demand curing for such materials32,33,34. Later, hydrogels like polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) and gelatin methacrylate (GelMA)43,44 were printed ex-vivo and similar hydrogels with encapsulated hardening agents were printed in-vivo45 with ultrasound to re-demonstrate the concept of printing inside the body32. Lately, an ultrasonic horn with a concave front surface has been utilized as the primary ultrasound source to create an acoustic focal region46 and print filaments of thermoset materials. However, the process lacks the practical resolution needed to create 3D objects. Additionally, an inexpensive sound-based 3D printer was reported where a silicon elastomer and egg white were solidified47. More recently, our research group introduced a holographic approach to DSP48, where pressure patterns created using acoustic holography techniques at an image plane are solidified simultaneously.

These advancements in sound-based additive manufacturing have opened new possibilities for remote and localized printing, with successful proof-of-concept applications across various materials. In fact, our research group’s introduction of a new paradigm, Remote Distance Printing (RDP), demonstrated the feasibility of minimally invasive printing through optically opaque barriers, such as biological tissues, for the first time32. However, as technology continues to evolve, significant challenges remain. Despite advancements in the initial sound printing concept through Direct Sound Printing32, Self-Enhancing Printing43, Continuous Sound-Based Production of Thermosets49, Desktop Direct Sound 3D Printing47, and Holographic Direct Sound Printing48 technologies, challenges remain in achieving complex printed parts, high resolution, practical small feature sizes, and the fabrication of functional microstructures.

In order to address these limitations, this work introduces Proximal Sound Printing (PSP), a novel sound-based 3D printing approach capable of printing unmodified, heat-curing thermosets such as PDMS, without requiring material modification or post-curing additives. By leveraging high-intensity focused ultrasound to induce localized sonochemical reactions, PSP achieves direct polymerization at microscale resolution and overcomes challenges in resolution improvement, multi-material printing, and fabricating complex structures in sound-based additive manufacturing. Unlike light- or heat-based methods, PSP supports using commercially available heat-curing resins such as PDMS without auxiliary heating or toxic photoinitiators. We demonstrate the capabilities of PSP through the fabrication of microstructures, which will be discussed in detail. PSP provides a versatile and precise solution for functional 3D printing, filling a critical knowledge gap and combining enhanced practicality with the unique advantages of sound-based methods. A detailed comparison of PSP with existing light-, heat-, and sound-based AM technologies is provided in Tables S1 and S2 in the Supplementary Information in order to better understand these advancements.

Results and discussion

PSP mechanism and 3D printed microstructures

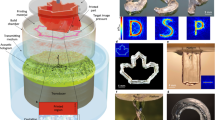

Figure 1a illustrates the schematic view of PSP. Ultrasound waves generated by a spherically focused transducer are transferred to the printing spot through an integrated guiding acoustic chamber. The tip of this chamber, called the apparatus tip, features a printing aperture at the focal location with a diameter of ID, covered by a thin acoustic barrier (Fig. 1b). The acoustic barrier, composed of a thin aluminum film, is designed to withstand high acoustic pressure while allowing ultrasound wave transmission. To seal the aperture in the acoustic chamber, thin aluminum film was used due to its low thickness, minimal acoustic attenuation, mechanical durability, and ease of shaping. Aluminum film was used to seal the aperture through which ultrasound propagates, effectively preventing water leakage while maintaining acoustic transmission. Printing materials are injected through the material injection channels and directed to the printing area in front of the aperture.

a Schematic of PSP. b A detailed view of the guiding acoustic chamber’s tip showing printing aperture covered with the barrier and the creation of SUAR in the vicinity of the barrier inside the printing material. c The ‘DSP’ letters printed by DSP (top) and PSP (bottom). d (i) 3D printed Y-channel microfluidic chip using PSP including 300 µm inlet channels and 500 µm main channel (ii) an illustration of laminar flow inside a main channel of the chip. e (i) Fabricated serpentine micromixer consisting of two inlets and an outlet with 500 µm channels with detailed illustrations of (ii) two distinctively colored water streams injected into the device, (iii) a mixed flow stream at the outlet of the micromixer. f 3D printed cross section of an airfoil NACA-0024 and its arbitrary internal stiffeners. g (i) 3D printed microcantilever, (ii) deflected microcantilever due to a water droplet at its tip

In the PSP process, the chemically active acoustic cavitation region is formed in the proximity of the barrier and inside the printing material (Fig. 1b). This region solidifies the liquid resin or mixture through sonochemical polymerization and prints solid regions onto the substrate, mounted on a platform, or top of previously deposited and solidified regions, called the sonochemically ultra-active reactor (SUAR).

The platform or substrate, moved by a motion manipulator, positions the SUAR along a pre-designed path to create the desired part pixel by pixel. The resolution and internal structure of objects printed using the PSP are influenced by the attributes of the transducer driving pulse (frequency f, electrical power P, and duty cycle DC), characteristics of the build materials (viscosity, mixing ratio of the monomer to curing agent additives, and mixture ratio), and the motion of the transducer (velocity and acceleration).

Different internal structures of produced parts result in a range of properties, from optically fully transparent to opaque. The resulting opacity is influenced by the inherent porous structure of the printed part, which is controllable by adjusting the PSP input parameters32.

We subjected the PSP to practical testing and applications to enhance our understanding of how PSP parameters intricately shape internal structures and optical transparency. The two sets of fabricated letters ‘DSP,’ illustrated in Fig. 1c at the top and bottom, are made from PDMS using both the DSP and PSP methods (using ID = 1.5 mm), respectively. The details regarding 3D printing with PSP and the subsequent post-processing steps are explained in the Methods. Post-processing involves placing the printed parts in an oven to evaporate residual isopropanol (IPA). As reported in previous studies30,32,48, FTIR analysis confirms that this heating step has a negligible impact on additional polymer conversion, showing minimal further reduction in the Si–H absorption band.

A simple visual comparison between the fabricated objects in Fig. 1c clearly demonstrates the superiority of PSP in terms of printing resolution and accuracy. With DSP, the line thickness of the letters is ~2 mm, whereas PSP yielded a significantly finer thickness of 200 μm, capable of producing microstructures and microsystems. This feature size reduction attests to more than one order-of-magnitude improvement in practical feature size achieved in PSP, making it ideal for 3D printing of PDMS microstructures.

PSP’s capability to fabricate fine microstructures was demonstrated by changing the printing aperture size (ID). This was demonstrated by printing a small ‘DSP’ letter and microstructures such as microfluidic devices using ID = 1 mm and 1.5 mm, respectively, as illustrated in Fig. 1c bottom, d, and e. The microfluidic Y-channel Fig. 1d–i comprises two inlets and an outlet with a diameter of 1.5 mm. The inlet channels (300 µm) and the main channel (500 µm) were created by printing two adjacent walls with an equivalent gap (see Methods). Figure 1e displays a 3D printed serpentine micromixer using PSP (see Methods). The micromixer consists of two inlets and an outlet with 500 µm channels. To present the performance of both the microfluidic Y-channel and micromixer device, two differently colored water solutions were injected into the inlets. The resulting distinctive colored streamlines (Fig. 1d-ii and Supplementary Video 1) along the main channel of the Y-channel chip serve as evidence of this device’s dominant laminar flow regime. In contrast, a comparison between Fig. 1e-ii and e-iii demonstrate the efficiency of the serpentine micromixer in mixing the injected solutions (see Supplementary Video 2).

We utilized PSP to fabricate objects with intricate micro features. Figure 1f presents a 3D printed cross-section of an airfoil NACA-0024 with arbitrary internal stringers employing the aperture ID = 1.5 mm. A detailed view in Fig. 1f highlights the high printing resolution achieved at a joint.

PSP demonstrates its versatility in fabricating microstructures for sensing applications, such as microcantilevers, as shown in Fig. 1g-i. Figure 1g-ii depicts the deflected cantilever with a water droplet at its tip. The observed deflection angle of 2.72° highlights the microcantilever’s sensitivity, supporting its potential integration into microfluidic devices. The microcantilever was printed using a printing aperture diameter of 1.5 mm.

PSP is capable of printing various thermoset materials, including epoxies, although their curing efficiency depends on formulation and viscosity. However, this study focuses on PDMS due to its widespread use in MEMS laboratories and critical role in microdevice fabrication. PDMS was selected as a representative material due to its biocompatibility, optical clarity, and flexibility, properties that make it particularly suitable for demonstrating the capabilities of PSP.

PSP process and material investigation

Insights into SUAR formation

Elaborating on the PSP’s diverse fabrication capabilities, we conducted a deeper investigation into the underlying processes, including examining the presence of SUARs, understanding the impact of ultrasound transmission through the barrier, and observing the spatial distribution of active chemical regions under ultrasound exposure. In order to achieve this, we conducted a series of sonochemiluminescence (SCL) experiments (see Methods) for ID = 1.5 mm and 4 mm (Fig. 2a–c). Figure 2a illustrates the setup schematic, where the chamber is filled with the luminol solution, and the region of interest defines the limits of the captured images. The SCL experiments reveal distinctive SUAR enveloping the apparatus tip located at various heights with respect to the platform (Fig. 2b, c). The blue light signifies a chemiluminescent reaction between hydroxyl radicals generated sonochemically within the hydrogen peroxide solution and luminol.

a Schematic of the setup used for SCL experiments inside the cavity filled with the luminol solution in which the apparatus tip is placed adjacent to the platform at different distances (h) and the blue light patterns of SCL captured using the DSLR camera. b, c SCL patterns captured using a DSLR camera for the aperture (b-i to b-iii) ID = 1.5 mm (c-i to c-iii) ID = 4 mm. d Schematic of an experimental setup for pressure map measurements. e Measured pressure maps using needle hydrophone for three planes located at different distances from the apparatus tip (i) dp = 0.24 mm (ii) dp = 0.74 mm (iii) dp = 1.3 mm. f, g Acoustic pressure and acoustic intensity fields computed from linear acoustic simulation. h Deposited acoustic power graph extracted from linear acoustic simulation results. i Simulation results of acoustic streaming inside a cavity filled with PDMS at different hs between the aperture and bottom of the cavity (i-1) hs = 1 mm (i-2) hs = 50 μm. j, k Footage from high-speed imaging of the 3D printing process and observation of SUAR during the fabrication of (j-i and j-ii) porous wall from PDMS with the mixing ratio of 10:1 and (k-i and k-ii) transparent wall from PDMS with the mixing ratio of 16:1, using the printing aperture diameter of 1.5 mm. Experimental conditions: P = 5 W, DC = 100%, f = 2.15 MHz; the ISO and exposure time of the DSLR camera for SCL experiments were set to 3200 and 30 s, respectively

Analysis of the images indicates that as the apparatus tip approaches the platform, the SUARs become more concentrated, ultimately leading to the formation of a distinctive reactive spot in the vicinity of the tip (Fig. 2b-iii, c-iii). To quantify the observed phenomena and provide practical guidelines for achieving usable SUARs, we used a non-dimensional pixel intensity graph to present the relationship between the aperture confinement ratio (ID/h) and the percentage of the area occupied by the SUAR (Fig. S1) confined between the apparatus tip and the substrate.

This operating map demonstrates how the SUAR area fraction increases as the distance between the tip and the substrate (ℎ) decreases, showing the effect of printing aperture diameter (ID) and operating parameter (h) on SUAR formation. It provides practical insights for optimizing apparatus tip configurations and controlling SUAR formation for the polymerization process.

A closer examination of Figs. 2b-iii, c-iii, and S1 reveals that, even though the transducer’s focal width (girth of 0.75 mm) is notably smaller than the printing aperture diameter (ID = 1.5 mm and 4 mm for Fig. 2b, c, respectively), the captured luminosity (blue spots) extends beyond the focal width at a proximity of h = 0.5 mm. The SUAR occupies 53% and 54% of the confined area between the apparatus tip and the substrate for h = 0.5 mm, corresponding to ID = 1.5 mm and ID = 4.0 mm, respectively.

This observation suggests that the barrier not only acts as a secondary ultrasound source with a width defined by the printing aperture (ID), which exceeds the focal size, but also helps confine the acoustic field near the aperture, enhancing localization, printing precision, and overall system stability. In addition, acoustic streaming could extend luminosity patterns by transporting the chemically active bubbles from the focal region to the surrounding medium.

Additionally, no unintentional curing was observed during prolonged printing. The polymerization effect remains highly localized within the SUAR, and the minimal macroscopic temperature rise does not initiate curing in the surrounding resin. Continuous resin injection through the tip prevents thermal buildup, ensuring that regions outside the focal zone remain uncured.

Despite some reflectivity, the PSP system demonstrated stable performance using aluminum film barrier and low acoustic power, without any observable degradation during prolonged operation. In fact, the barrier helps confine the acoustic field near the aperture, thereby enhancing localization and printing precision without compromising stability.

Pressure mapping and acoustic power deposition estimation

Figure 2b, c display the generation of the high-pressure regions close to the apparatus tip50. We conducted pressure mapping experiments inside the water to measure the absolute pressures at this location (see Methods). Figure 2d displays the schematic of the setup used for pressure mapping with a needle hydrophone. The transducer operates at an electrical power of P = 5 W and a frequency of f = 2.15 MHz. Pressure mapping is conducted at different distances, dp, with respect to the apparatus tip. Figure 2e(i–iii) show that the maximum pressure, pmax, of 6 MPa occurs at the location close to the tip, validating the observations from Fig. 2b, c.

All the electrical power is not used at the printing location due to the transducer’s efficiency and the acoustic reflection at the barrier. Therefore, only a fraction of power is deposited beyond the barrier in the printing material. This deposited acoustic power is calculated numerically for the printing conditions of f = 2.15 MHz, P = 5 W, and DC = 100% for ID = 1.5 mm, with a gap of 1.4 mm between the aperture and the platform (Fig. 2f–h). Figure 2f indicates that the barrier reflects the majority of transmitted ultrasound waves from the transducer into the acoustic chamber, leading to the formation of a high acoustic pressure zone with a maximum magnitude of pta = 9 MPa within the water. However, the maximum acoustic pressure within the printing material is pta = 1.25 MPa. Figure 2g displays the acoustic intensity field, Ia. The deposited acoustic power at different cross-sectional planes along the 1.4 mm gap within the printing material is shown in Fig. 2h. This figure reveals that the maximum deposited acoustic power, Pa|Max = 0.32 W, is generated at the surface of the barrier. Notably, this magnitude is 15 times lower than the applied electrical power to the transducer (P = 5 W). This finding provides valuable insight into how a low power level is required for successful PSP printing. In addition, the applied electrical power to the transducer was 20 W in the early demonstration of DSP32 but this power is reduced to 5 W in PSP, showing a 4 times reduction. Furthermore, Fig. 2h demonstrates that Pa|Max remains relatively constant in the vicinity of the barrier (hs < 500 µm). However, as the distance from the apparatus tip increases up to 1.4 mm, the deposited acoustic power experiences a reduction of ~30%. This insight into the spatial distribution of deposited acoustic power is crucial for optimizing printing conditions, such as the gap between the apparatus tip and the substrate and enhancing the efficiency of the PSP process.

Acoustic streaming investigation

To conduct a more comprehensive investigation of the printing process, we explored acoustic streaming through numerical analysis and experiments using a smaller chamber and tracing dispersed SiO2 microparticles (see Methods). Acoustic streaming is critical for achieving high-resolution and stable 3D printing, as excessive streaming can disrupt printed structures and compromise surface quality32,43,49. This approach goes beyond merely characterizing the printed parts by providing in situ insights through close observation of the print location. The results, including the velocity field with the pattern of streamlines, are presented in Fig. 2i and Fig. S2.

Figures S2a and b illustrate the experimental and simulation outcomes, respectively, for hs = 4.5 mm using an aperture ID = 1.5 mm. The maximum streaming velocity is 2.5 \(\times \,\)10-4 m/s at P = 5 W power, concentrated near the apparatus tip, while the streaming velocity near the platform surface is negligible. The presence of a vortex is evident in both sets of results. Despite slight differences, likely attributed to estimations in material properties (see Methods) and the application of the linear acoustic equation in simulation (see Methods for further details), Figs. S2a and b exhibit strong agreement between experimental and simulation results, including fluid velocities and streamline patterns.

Figure 2i-1 and i-2 show the simulation results for the same ID = 1.5 mm, electrical power of 5 W, and frequency of 2.15 MHz at distances hs = 1 mm and hs = 0.05 mm, respectively. The results indicate that decreasing the distance between the apparatus tip and the platform reduces the acoustic streaming velocity, reaching a negligible streaming velocity of 1.8 \(\times \,\)10-6 m/s at the shortest distance of hs = 0.05 mm. This velocity is confined to the infinitesimal volume between the tip and the platform, sharing the cross-sectional area with the printing aperture. This outcome supports the findings from Fig. 2b, emphasizing the relevance of the SUAR size to the gap between the aperture and the platform. Moreover, comparing the maximum acoustic streaming velocities between PSP (1.8 \(\times \,\)10-6 m/s) and DSP32 (3 \(\times \,\)10-3 m/s) reveals a dramatic 1600 times reduction in maximum streaming velocity during printing. This substantial reduction holds promise for significantly improving printing repeatability, defined as the PSP process’s ability to consistently reproduce feature sizes and internal structures under identical conditions, and practical resolution, while having minimal impact on the process.

PSP in action: insights from high-speed and temperature measurement

The results from SCL tests, streaming, and pressure mapping studies reveal that if the apparatus tip of the printer is placed close enough to the platform, the high-pressure zone with extremely low streaming velocity can be generated. This localized spot can induce polymerization in the region, leading to material solidification without the disturbing forces induced by streaming. The minimum layer thickness of 50 μm was used in this paper as a printing condition to achieve a minimum feature size of 200 μm (Fig. 1c). This fine layer thickness helps in minimizing reaction gradients and ensuring strong interlayer adhesion and can be implemented while using ID = 1 mm or 1.5 mm. However, a printing condition with a layer thickness of 500 μm is used for ID = 4 mm to maximize the deposition rate while still ensuring adequate interlayer bonding. This approach helps manage axial and in-plane reaction gradients, balancing deposition efficiency and print quality across different feature sizes.

In Fig. 2j and k, we present high-speed imaging footage of the printing process, showing the creation of walls with P = 5 W and f = 2.15 MHz. The printing was performed using the printing aperture diameter of 1.5 mm and employing PDMS with varying mixing ratios of 10:1 and 16:1. When electrical power and frequency are kept constant, the PDMS mixing ratio significantly influences the optical properties of the printed object, such that higher ratios (e.g., 10:1) produce porous structures, while lower ratios (e.g., 16:1) result in transparent ones32. Figure 2j-ii and k-ii depict printing porous and transparent layers from PDMS with mixing ratios of 10:1 and 16:1, respectively. Our observations from Fig. 2j, k, as well as Supplementary Videos 3 and 4, reveal that SUAR formation occurs close to the apparatus tip, approximately 50 µm away from either the platform or the previously printed layer, while the device moves at a feed rate of V = 240 mm/min. The formation of SUAR strongly depends on the power and frequency and is unaffected by the velocity, V. To illustrate the method’s practical application, we employed it to print the word ‘DSP’ (Fig. 1c) at P = 5 W, f = 2.15 MHz, ID = 1.5 mm, and V = 240 mm/min using PDMS with a mixing ratio of 10:1.

We also measured the temperature rise in the printing region using a thermocouple (see Methods) and an infrared (IR) camera. As shown in Fig. S3, the recorded temperature increases were ~26 °C (thermocouple) and 20 °C (IR camera), which are not sufficient to initiate on-demand polymerization of PDMS. This observation supports the hypothesis that sonochemistry, rather than thermochemistry, is the dominant mechanism enabling polymerization in PSP. The slight difference between these measurements arises from the nature of the sensing methods: the thermocouple records localized contact temperature at a specific point, whereas the IR camera captures non-contact surface temperature over a broader area.

Thermal imaging with an infrared (IR) camera after a 15-min printing process, as shown in Fig. S3c, confirmed that the temperature of the apparatus tip remains close to that of the printing material, indicating no significant local heating. Additionally, no visible deformation of the barrier (aluminum thin film) or the surrounding 3D printed acoustic chamber (Fig. 1) was observed, even after prolonged use, demonstrating the thermal stability and repeatability of the PSP setup.

All printing was performed at room temperature (20–25 °C) without external heating. Although heat can promote PDMS polymerization, our results show that object formation occurs through ultrasound-induced effects. The slight temperature rise near the tip (Fig. S3) is insufficient for thermal curing, confirming that sonochemical activation is the primary mechanism, as previously reported32,44,49.

Additionally, long-term printing experiments (up to 1 h) demonstrated stable printing performance, with no loss of resolution or fidelity. The PSP system’s guiding chamber and tip, fabricated from 3D-printed plastic, showed no thermal degradation. The temperature of the acoustic propagation medium (water) in the acoustic chamber increased by ~10 °C over the course of a printing session, but this did not affect system stability. Low-deposited acoustic power helps mitigate excessive heating and contributes to consistent operation.

Effect of PSP printing parameters on fabricated structures

Impact of process parameters on feature size and resolution

A series of tests was conducted by printing lines with varying process parameters to investigate the impact of PSP process parameters on feature properties, including size and internal structure. These parameters included electrical power P, duty cycle DC, frequency f, and the mixing ratio of the build material.

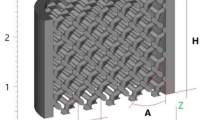

Figure 3a–c display the relation between the printed lines’ measured thickness (feature size) against variable powers, duty cycles, and frequencies for a printing aperture diameter of 2.65 mm (nominally 2.5 mm). In these experiments, the layer thickness was kept constant at hs = 0.2 mm. Figure 3a shows the thickness of the printed lines across a range of powers from 5 W to 30 W, with higher power resulting in a larger thickness. Figure 3a also presents the estimated acoustic power deposited in the printing material versus the polymerized feature size for different input power levels. This allows a visual comparison of feature size as a function of deposited energy. Given the fixed layer thickness (ℎs = 0.2 mm) in our experiments with ID = 2.65 mm, the resulting feature volume serves as a reliable approximation of the polymerization rate. These results highlight the efficiency of PSP in achieving material conversion with substantially lower acoustic power compared to DSP.

a Graphs illustrating variations in the thickness of printed lines and the deposited acoustic power (Pa) as functions of applied power and volume of the polymerized feature, respectively. b, c Graphs illustrating variations in the thickness of printed lines corresponding to changes in duty cycle and frequency, respectively. d–f Illustration of XY-plane resolution through the printing of parallel lines, each with a thickness of 0.5 mm and varying gaps, fabricated with ID = 1.5 mm. g Cross-sectional resolution display of multiple parallel lines with varying gaps printed using ID = 1.5 mm. h Schematic of printing parallel lines with line thickness (w) and gap (s) for a resolution study of PSP. i Fabricated transparent plane by 3D printing multiple parallel lines with w = 2.3 mm and no gap (s = 0 mm) using ID = 3 mm. j Fabricated maple leaf with w = 3.5 mm using ID = 4 mm. k-m 3D printed porous and transparent lattice structures with w = 500 μm using ID = 1.5 mm. Experimental conditions: f = 2.15 MHz, (d−f, g, k−m) P = 10 W, DC = 50% i and j P = 30 W, DC = 100%, PDMS mixing ratio (d−f, g, j, l, 10:1, i, m) 16:1

Higher DC results in larger printed line thickness (Fig. 3b). At a constant power of 25 W and frequency of 2.15 MHz, adjusting the duty cycle has a comparable effect on the thickness of the printed lines, nearly equivalent to the impact of changing the power at constant frequency and duty cycle (Fig. 3a). However, at lower power levels, attempting to reduce the duty cycle may lead to unsuccessful printing. For example, if P = 15 W, setting the DC < 60% makes the printing process unsuccessful, potentially attributed to a lack of SUAR formation at such a low-duty cycle. Increasing the printing frequency, f, results in a smaller feature size (Fig. 3c). We applied a range of frequencies for line printing based on the transducer’s manufacturing specifications, ranging from 1.8 MHz to 2.5 MHz (0.7 MHz band). Therefore, a ~ 0.4 mm reduction in the line thickness was observed when the frequency was increased by 0.7 MHz. Additionally, the ultrasound frequency affects the internal structure of PSP-printed objects; lower frequencies tend to result in smaller pores, consistent with observations from our earlier DSP study32.

The duty cycle and power can be tuned at a constant frequency to control the feature size more effectively. Notably, altering frequency affects the internal structure of the fabricated object32. Consequently, in this research, we selected the transducer’s first harmonic (f = 2.15 MHz) as the constant transducer’s driving frequency for conducting experiments and printing.

Additionally, Fig. 3a–c demonstrate that the printing parameters, including power, duty cycle, and frequency, which together determine the total input energy, directly influence feature size and material conversion (polymerized volume). In this study, material conversion is approximated by the product of feature size and layer thickness. Higher input energy generally results in greater polymerized volume and larger printed features. Although the polymerized volume varies, prior FTIR analyses30,32,48 have shown consistent reductions in the Si–H absorption band across materials with different viscosities. This indicates that viscosity impacts feature size but not the degree of polymer conversion.

Maintaining a constant frequency, the XY printing resolution in PSP relies on input parameters, including power and duty cycle. In contrast, the Z-printing resolution in PSP depends on the resolution of the z-axis feed drive and the SUAR size.

We conducted experiments by printing sets of parallel lines with varying gaps, systematically reducing the gap width until they were completely filled.

Figure 3d–f illustrate the created lines with thickness w = 500 μm with gaps, s, ranging from 1.2 mm to 0.15 mm, by f = 2.15 MHz, P = 10 W, and DC = 50%, ID = 1.5 mm (given that the PDMS mixing ratio in this experiment is 10:1, resulting in porous printed parts). Figure 3g provides a cross-sectional view of printed parallel lines with noticeable gaps, indicating that reducing the gap, s, to less than 150 µm leads to the merging of lines.

In PSP, the layer thickness remains uniform as each layer is confined between the printing tip and the underlying surface. Surface roughness measurements using confocal microscopy revealed smoother top surfaces (\({S}_{a}\) = 0.230 μm, \({S}_{q}\) = 0.327 μm) and rougher sidewalls (\({S}_{a}\) = 3.494 μm, \({S}_{q}\) = 4.292 μm), consistent with the layer-by-layer deposition process, as shown in Fig. S8. Notably, sidewall roughness increased with the number of stacked layers, likely due to cumulative alignment deviations and minor variations in SUAR formation during successive printing cycles.

Influence of process parameters on internal structure

Reducing the volume of the curing agent in the PDMS mixture enhances the transparency of the printed objects32. Therefore, we adjusted the mixing ratio of PDMS from 10:1 to 16:1 by reducing the curing agent to create a transparent structure. This was achieved by printing a series of parallel lines with zero gaps, s = 0. Figure 3h, i show the schematic of the printing process and the printed transparent structure, respectively. The printed part’s transparency is evident when placed over the colored text.

The printing aperture diameter, ID, is a key factor in PSP, where a smaller ID leads to a smaller feature size. In Fig. 3j, the maple leaf is printed with ID = 4 mm, resulting in lines that are 3.5 mm thick. Conversely, in Fig. 3k and l, lattice structures are printed with ID = 1.5 mm, resulting in thinner lines measuring 500 μm. The use of different PDMS mixing ratios of 10:1 and 16:1 produces porous and transparent objects, respectively (Fig. 3l, m). Notably, while the XY printing resolution in PSP can be fine-tuned by adjusting process parameters, the printing aperture diameter is an additional input parameter that can conveniently control the feature size by modulating the sound fields interacting with printing materials. Moreover, the printing aperture’s shape is another determining printing resolution. Deviations of the printing aperture’s shape from a circular form lead to inhomogeneities in printing resolution.

Deposition rate and material compatibility in PSP

Changing the size of the printing aperture diameter, ID, directly impacts the deposition rate in PSP, significantly influencing the overall process performance. In our experiments, PSP achieved a volumetric deposition rate of ~250,000 mm3/hour (ID = 4 mm), which is notably higher than DSP (~15,000 mm3/hour) and comparable to Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) and DIW32. Fig. S4 comprehensively compares volumetric deposition rates versus resolution among DSP, light and heat-based AM technologies and PSP. This figure illustrates that the PSP process developed in this paper is a viable 3D printing method, offering comparable feature size and printing speed to commonly used AM processes.

In order to summarize the advancements of PSP, detailed comparisons with existing sound-, light-, and heat-based AM technologies are provided in Tables S1 and S2 of the Supplementary Information.

While other 3D printing methods, including ultrasound-based techniques (Table S1), have demonstrated the use of silicone elastomers such as PDMS, they have primarily faced limitations due to the inherently low viscosity of these materials, often requiring rheological modification or specialized printing strategies to achieve structural stability. In contrast, the PSP method enables the direct fabrication of functional microstructures using unmodified PDMS, eliminating the need for material alteration or viscosity enhancement.

Fabrication of functional objects and characterization

We designed and fabricated two series of microcantilevers (see Methods) to highlight PSP’s capabilities in fabricating functional objects, as shown in Fig. 4a. Polymeric microcantilevers can be integrated into microsystems for physical and biological applications such as sensing51 and biofunctionalization52 devices. The sensitivity of fabricated beams is determined by measuring their linear stiffness through static deflection-load experiments (see Methods).

Figure 4b shows the average induced force due to the applied displacement with a linear behavior. The slope of each graph determines the average linear stiffness corresponding to each series of microcantilevers, as presented in Fig. 4c.

a Two sets of 3D printed microcantilevers (Cantilever 1 and Cantilever 2) with different dimensions printed by aperture ID = 1.5 mm. b, c Force-displacement graphs and stiffness comparison, respectively, for 3D printed cantilevers. d An example of multi-material printing of maple leaf object from three colors of Sylgard-184. e Images of the 3D printed OBML letters made from luminous colloidal solution captured (i) at ambient light and (ii) in the dark room. f Schematic of printing patterns for (i) horizontal and (ii) transverse fabrication of dog-bone samples. g Molded, horizontally, and transversely 3D printed dog-bone samples from different PDMS mixing ratios for tensile tests. h, i Stress-strains graphs and Young’s modulus comparison, respectively, of fabricated dog-bone samples. Experimental conditions: f = 2.15 MHz, (a, e) P = 10 W, DC = 50%, (d) P = 30 W, DC = 100%, (g) P = 30 W, DC = 50%, PDMS mixing ratio (a−e) 10:1

The results indicate that increasing the length will reduce the stiffness of the cantilever. The computed stiffness of 6.8 N/m is comparable to the stiffness reported previously53, where photolithography fabricates PDMS microcantilevers, and the reported stiffness is 8.7 N/m.

The optical opacity of the printing material does not affect the PSP process. This unique characteristic allows PSP to use opaque materials in the form of pure chemical compounds or colloidal solutions. Additionally, the design of the PSP apparatus enables the deposition of different materials individually or simultaneously (Fig. 1a). We utilized PSP to perform multi-material printing (see Supplementary Video 5 and Methods) to fabricate a part with a line thickness of 3.5 mm (Fig. 4d).

In another attempt, we printed the word ‘OBML’ using a suspension of PDMS and phosphorus glowing green powder (see Supplementary Video 6), presenting the PSP’s capability to print colloidal solutions (Fig. 4e and Fig. S5). The printing process was conducted at P = 10 W, DC = 50%, f = 2.15 MHz, and ID = 1.5 mm. After the printing process was completed, the object (Fig. 4e–i) was exposed to ambient light for an hour and then transferred to a dark room. Figure 4e-ii displays the object in the dark room, emitting a uniform glowing light. The outcome validates the capability of the PSP to print colloidal suspensions.

Although this study focuses on microdevice fabrication, PSP is also capable of printing complex geometries, such as octet truss structures. This can be achieved either by directly printing overhanging features or by employing sacrificial substrates, depending on the properties of the printing material. Epoxy, in particular, is well-suited for such structures due to its favorable mechanical strength and curing characteristics.

Classical tensile tests were performed to investigate the effects of the printing process and the influence of printing direction on the mechanical properties of the objects (see Methods). We printed dog-bone tensile test specimens with different printing patterns, including longitudinally and transversely oriented paths with respect to the tensile direction (Fig. 4f). All samples are presented in Fig. 4g, with Fig. 4h displaying stress-strain curves and Fig. 4i illustrating computed Young’s modulus.

In the case of samples with a 10:1 ratio, a notable 21.5% reduction in Young’s modulus, E, was observed compared to the molded counterparts. However, this discrepancy diminishes with a decrease in the mixture’s curing agent presence.

In the PSP process, decreasing the amount of curing agent leads to the 3D printing of a less porous and more flexible object, aligning its Young’s modulus with that of the molded component (Fig. 4i). Due to its porous structure, the printed part with a 10:1 ratio exhibits an ~6% lower elongation at break compared to the molded counterpart (Fig. 4h).

However, the variation in elongation between the printed and molded parts diminishes with a decrease in the mixing ratio, which is attributed to a reduction in the number of pores within the object. This observation is supported by the stress-strain results for mixing ratios 13:1 and 16:1, which reveal a 1.7% and 0.87% difference in elongation between the printed and molded parts, respectively. In Fig. 4i, Young’s modulus of the transversely printed part is slightly lower by 1.6% compared to the longitudinally printed counterpart. This difference arises during the fabrication process, where the transverse pattern depicted in Fig. 4f-ii involves stacking more porous lines in the direction perpendicular to the tensile force than longitudinal patterns. However, the reduction in porosity for the 16:1 ratio exhibits a remarkable convergence in Young’s modulus of the printed parts (Fig. 4i). Consequently, it can be concluded that the printing direction has a minimal impact on the overall mechanical properties of the object.

Conclusion

We present an innovative sound-based 3D printing mechanism, PSP, that harnesses ultrasound waves to fabricate microstructures and 3D objects by inducing rapid phase transformation from liquid to solid in heat-curing resins through acoustic cavitation and sonochemical reactions. The presence of SUAR, where crucial polymerization reactions occur, is confirmed through experiments involving SCL and high-speed imaging.

A breakthrough aspect of PSP, compared with existing sound-based AM methods, is its capability to execute the printing process at extremely low deposited acoustic power, as low as 0.32 W. This drastically reduces the fluid motion during printing and prevents undesired disturbances that could degrade resolution. In contrast with other ultrasound-based AM methods, which often require higher acoustic intensities that cause turbulence and limit fine feature control, PSP provides a stable and controlled polymerization environment, enabling higher precision (a practical feature size of 200 µm) and more reliable fabrication. Additionally, its low-power operation makes PSP energy-efficient and compatible with sensitive environments where excessive heat or mechanical vibrations must be minimized. A comparative analysis of PSP and existing sound-based 3D printing technologies is presented in Table S1. Additionally, Table S2 comprehensively compares PSP and light- and heat-based 3D printing methods.

The present work achieves a practical feature size of 200 µm, representing an order-of-magnitude improvement over the DSP method. This advancement is illustrated by successfully fabricating functional microstructures, including microfluidic channels and microcantilevers from polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS), a material widely used in microsystems for its biocompatibility and optical transparency. Fine-tuning printed structures’ feature size as well as the ability to create porous or transparent internal structures is achieved by systematically manipulating key printing parameters such as printing material, printing aperture diameter (1.5–4 mm), ultrasound power (5–30 W), frequency (1.8-2.4 MHz), and duty cycle (30−100%). Material characterization further reveals that the printing process is independent of the printing direction, validating its robustness.

In addition, PSP demonstrates the ability to print multi-material structures, a capability not previously shown by ultrasound-based methods.

The extremely low deposited acoustic power of 0.32 W required for PSP, combined with the green chemistry aspect of sonochemistry with no toxic byproduct during or after printing, makes the PSP process an appealing and environmentally friendly 3D printing technology. The mobility of the PSP mechanism allows it to be seamlessly integrated into CNC or robotic arms, enhancing process control and elevating printing accuracy and precision. Moreover, in applications where onsite printing is required, it is desirable to operate at room temperature to avoid damaging the surrounding environment of the printing location. In fact, PSP presents an ideal solution for such scenarios with its low-power operation and room-temperature polymerization.

In conclusion, PSP addresses key limitations of existing ultrasound-based AM technologies by providing a scalable, precise, and sustainable method for 3D printing functional device structures. Unlike previous ultrasound-based techniques that primarily demonstrate filament-based structures with feature sizes in the 1–2 mm range, PSP achieves a practical feature size of 200 µm, representing a significant improvement in precision. With its versatility, environmental benefits, and capability to achieve high-resolution printing at low power, PSP opens new avenues for producing customized and specialized macro/microstructures across various applications using sound waves.

Methods

Materials

PDMS preparation for 3D printing tests

SYLGARD 184, a polydimethylsiloxane kit (obtained from Krayden, Canada), is utilized. The PDMS monomer and curing agent are combined in specified ratios and degassed for 30 min under a vacuum.

Luminous colloidal solution of PDMS test: The colloidal solution is created by adding 10% w/w of commercially purchased luminous pigment powder to the base monomer. The mixture is homogenized by a homogenizer (Omni Mixer Homogenizer, Omni International, US) for 10 min. Then, the curing agent is added to the prepared mixture.

Colored PDMS for 3D printing tests

The PDMS color is altered by introducing a 2% w/w oil-based dye (Winsor & Newton, UK) to the base monomer before mixing it with the curing agent.

Luminol solution for SCL experiments

A solution of 1 mM luminol (3-Aminophthalhydrazide, obtained from Sigma-Aldrich, Canada) is prepared, and its pH is adjusted to 12 by adding NaOH (from Sigma-Aldrich, Canada), with real-time pH measurement using a pH 315i meter (Wissenschaftlich-Technische Werkstätten, WTW, GmbH, Germany). Subsequently, 0.5 M sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) is dissolved in the solution, prepared by heating sodium bicarbonate (NaHCO3 or baking soda) at 100 °C.

Transducer, pulse generator, and needle hydrophone

This research employs the HIFU transducer H-148, purchased from Sonic Concepts Inc., USA. The H-148 features a fundamental frequency of 2.15 MHz, with a minimum frequency of 1.46 MHz and a maximum frequency of 3.2 MHz. It has an active diameter of 64 mm, a central hole diameter of 22.6 mm, a radius of curvature measuring 63.2 mm, and a focal depth from the exit plane of the transducer housing at 51.54 mm. The −6 dB focal size at the fundamental frequencies is 0.7 × 5.33 mm. H-148 exhibits an 85% efficiency in converting acoustic power from electrical power. To drive the H-148, the TPO-102 transducer power output device from Sonic Concepts Inc., USA, is utilized, offering sinusoidal output powers ranging from 5−210 Watts. Temporal pressure measurements in the water near the printing aperture/barrier are conducted using a 0.2 mm diameter needle hydrophone (model no. D1602) with a hydrophone booster amplifier from Precision Acoustics Ltd., UK.

The printing process using PSP

PSP is not strongly dependent on material viscosity, which allows broad flexibility in printable materials. This was demonstrated by successful fabrication using silicone resins with viscosities ranging from 3.5 Pa·s (Sylgard 184) to 123.8 Pa·s (Sylgard 186), without the need for rheology modifiers.

The printing process can be executed through two methods. In the first approach, the guiding acoustic chamber is filled with degassed deionized water (Fig. 1a). The PSP device can be affixed to a robotic arm (Fig. S6) or maintained stationary while the substrate is connected to the CNC machine. The printing material is introduced into embedded material injection channels within the device. By either moving the PSP or adjusting the substrate’s position, the tip of the PSP is positioned at a specified distance (hs) relative to the substrate, serving as the initial location for printing (reference position). The design of 3D objects is accomplished using computer-aided design/manufacturing software, specifically CATIA™. In the cases where the PSP is mounted on a robotic arm, continuous material injection occurs as the motion manipulator guides the PSP along the generated path until the desired 3D object is fabricated over the substrate. Alternatively, when the PSP remains stationary, the substrate is connected to the CNC and moved along the designated path to create the 3D object. In the second method, the PSP does not incorporate embedded injection channels, and its tip is immersed into the printing cavity filled with the printing material, following the same procedural steps outlined for the printing process involving the PSP with embedded injection channels. This helps capture clearer video footage.

To achieve the final product, the printed component undergoes a thorough cleaning process. It is washed and rinsed with isopropanol alcohol (IPA) to eliminate any residual unpolymerized PDMS. Subsequently, the treated parts are placed in an oven at 50°C for 30 min.

3D printing of microfluidic chips

Following the aforementioned printing process using PSP, the fabrication of a microfluidic Y-channel and serpentine micromixer involves the precise printing of channel walls with a height of 500 μm, using a printing aperture diameter of 1.5 mm. After applying post-processing, 3 mm PDMS is used to encapsulate the channels. Before bonding the films to the printed channels, inlets and outlets are punched, and one side of the films is coated with a thin layer of PDMS 10:1 resin to serve as an adhesive. Following this preparation, the films are carefully placed over the printed channels, and the assembled components undergo a 1-h curing process in a 65°C oven to establish a durable bond. Subsequent to bonding the films to the channels, an injection of PDMS 10:1 resin into the gaps between the film and the substrate may be performed to enhance the bonding between the components further. In this case, the chip is subsequently placed in an oven to facilitate the polymerization of the injected resin.

Process observation experiments

The high-speed camera FASTCAM SA-Z (Photron Inc., USA) is employed for both high-speed imaging and particle tracing experiments. Particle tracing images are captured using an Optem Fusion 7:1 lens setup, and a variable-power halogen light source is utilized consistently throughout all experiments.

SCL experiments

The setup for SCL experiments includes the PSP apparatus attached to a computer numerical control (CNC) machine from Stepcraft Inc., USA. It consists of a plexiglass chamber filled with a luminol solution and a plexiglass platform positioned at the container’s base (Fig. 2a). This entire setup is placed in a dark room. Image acquisition was performed using a DSLR camera set at ISO 3200 with an exposure time of 30 s.

Microcantilevers fabrication and stiffness measurements

Two series of microcantilevers with width (W) and thickness (thk) of 1.27 mm and 0.76 mm, respectively, and different lengths of 2.8 and 3.3 mm were printed with P = 10 W, DC = 50%, f = 2.15 MHz, and ID = 1.5 mm from the 10:1 PDMS. The microcantilevers’ stiffness was evaluated through static deflection-load experiments conducted with the FemtoTools FT-MTA02 Micromechanical Testing and Assembly Station (FemtoTools AG, Switzerland), shown in Fig. S7. This advanced apparatus integrates a micro-robotic system with nanometer manipulation resolution in XYZ and a universal measurement stand equipped with a digital microscope. The attached sensing probe features a needle tip section measuring 50 × 50 μm, a thickness of 50 μm, a force range of ±100,000 μN, and a resolution of 5 μN. Throughout the experiments, the micro-robotic system consistently applied displacement to the tip of the beams until a maximum deflection of 400 μm was reached. The software dedicated to the system continuously recorded the resistive forces induced in the beam due to applied deflections.

Acoustic pressure measurement in water (Pressure map)

Pressure field mapping on the PSP apparatus, ID = 1.5 mm, was conducted utilizing a needle hydrophone attached to a three-axis CNC system. The transducer operated at f = 2.15 MHz, P = 5 W, DC = 100%. A Tektronix DPO 2024B oscilloscope (Tektronix, USA) was employed to acquire the hydrophone’s output at various points. The recorded output was then converted to pressure units using the calibration factor provided by the manufacturer. The measurements were carried out on three planes (14 mm × 14 mm) along the axial direction in front of the barrier (Fig. 2d). For each plane, the measurements were taken with a lateral step size of 0.5 mm in the XZ plane. The final pressure field images were generated using MATLAB.

Acoustic streaming experiments

The visualization of acoustic streaming near the apparatus tip involved monitoring the trajectory of SiO2 microparticles dispersed in the PDMS monomer. The PDMS monomer, mixed with ~100 µm polystyrene micro-particles, was introduced into a two cm-high acrylic chamber. The apparatus tip with the printing aperture diameter of 1.5 mm was immersed in the suspension. Tests were conducted with the transducer driving at f = 1.5 MHz, P = 5 W, and DC = 100%. The acoustic streaming was captured by employing a high-speed camera.

Temperature measurement

The temperature in the printing region was measured during the printing of a straight line using an embedded thermocouple. A 1 mm-thick glass slide with a 0.8 mm-diameter hole was used as the printing substrate. A T-type copper-constantan thermocouple (diameter: 0.25 mm, Omega Engineering, Inc.) was inserted through the hole so that its tip was aligned with the glass slide’s surface to avoid disturbing the printing process. To monitor temperature during the printing process, the thermocouple was positioned directly in the ultrasound focus zone along the printing path, as shown in Fig. S3a-i and ii. The tip was placed ~50 μm above the glass substrate surface, matching the height of the first printed layer, thereby ensuring it was located within the printed structure during curing. This placement enabled localized temperature measurement relevant to the reaction zone. The hole was located at the center and mid-length of the straight line, as shown in Fig. S3a-ii. The thermocouple was connected to a data acquisition system (National Instruments NI cDAQ™ 9171, US), and temperatures were recorded using LabVIEW software over 3 s as the 3D printer reached and passed over the thermocouple’s tip. The printing was performed at a driving frequency of 2.15 MHz, electrical power of 10 W, and a duty cycle of 50%, using an aperture diameter of 3 mm and PDMS 10:1 as the printing material.

Tensile tests

The PDMS mixing ratios of 10:1, 13:1, and 16:1 were selected for 3D printing type V dog-bone samples, while control samples were conventionally molded. The printing was conducted at a driving frequency, electrical power, and duty cycle of 2.15 MHz, 25 W, and 100%, respectively, using ID = 3 mm. The samples were subjected to standard tensile tests using a motorized test stand (Z5, from Hoskin Scientific LTD.) equipped with a 1000 N load cell, following the ASTM D638. Testing was conducted at a 10 mm/min displacement rate, and specialized software recorded the force-displacement data. Young’s modulus was determined by analyzing the slope of the initial linear segment of the stress-strain curve.

Multimaterial printing

Three different colors of Sylgard-184 were injected into the channels embedded in the PSP apparatus (Fig. 1a), to fabricate a part (Fig. 4d). The printing was conducted at P = 30 W, DC = 100%, f = 2.15 MHz, and ID = 4 mm. After printing each material, the material injection channels were flushed, and the next material was loaded and injected.

Linear acoustics and acoustic streaming simulations

Acoustic streaming is a steady-state fluid flow that is generated by acoustic waves in a liquid. The momentum produced by acoustic energy when passing through a liquid is transferred to fluid particles. In order to characterize this phenomenon, we have performed an axisymmetric simulation in Comsol Multiphysics 6.0. The analysis was performed in three steps. First, the acoustic pressure inside the printing material, including PDMS fluid, is determined by performing the linear acoustic study. The Helmholtz equation in the frequency domain50 for the whole PSP apparatus, including the transducer, acoustic chamber, water, printing aperture, barrier, and printing liquid, is solved. Having the acoustic pressure magnitude inside the PDMS, the volume force acting on PDMS fluid is determined by solving the continuity equation and the Navier–Stokes equation for a viscous incompressible fluid54:

where \({\vec{U}}_{l}\) is the streaming velocity, \({P}_{f}\) is the static pressure, \({\mu }_{d}\) is the dynamic viscosity of the medium, and \({\rho }_{a}\) is the steady state fluid density. \({\vec{F}}_{A}\) is the force acting on the fluid by the presence of the sound and can be denoted as54:

Finally, fluid flow generated by the volume force is solved in a turbulent \(\kappa -\varepsilon\) model to achieve streaming velocities.

In these studies, the input parameters for materials are as follows for water \(c\) = 1483.6 \(\frac{m}{s}\), \(\rho\) = 998 \(\frac{{kg}}{{m}^{3}}\), \(\mu\) = 0.89 \({mPa}.s\), \({\alpha }_{0}\) = 0.217 dB/m; for PDMS (10:1 mixing ratio) \(c\) = 1020 \(\frac{m}{s}\), \(\rho\) = 965 \(\frac{{kg}}{{m}^{3}}\), \(\mu\) = 3.5 \({Pa}.s\), \({\alpha }_{0}\) = 147.66 \(\frac{{dB}}{m}\); for PDMS base resin \(c\) = 1020 \(\frac{m}{s}\), \(\rho\) = 1030 \(\frac{{kg}}{{m}^{3}}\), \(\mu\) = 5.1 \({Pa}.s\), \({\alpha }_{0\,}\,\)= 147.66 \(\frac{{dB}}{m}\); for aluminum thin film \(c\) = 6320 \(\frac{m}{s}\), \(\rho\) = 2700 \(\frac{{kg}}{{m}^{3}}\), where \(c\), \(\rho\), \(\mu\) are the fluid’s speed of sound, density, and dynamic viscosity, respectively. The \({\alpha }_{0}\) is the attenuation of material at \({f}_{0}\) = 1 \({MHz}\) which is used for the calculation of material’s attenuation at different frequencies using the power law formula in the form of \(\alpha\) = \({\alpha }_{0}\) \({\left(\frac{f}{{f}_{0}}\right)}^{2}\) where α represents the attenuation of material in (\(\frac{{dB}}{m}\)) at a frequency of \(f\) (\({MHz}\)).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Code availability

The open-source MATLAB and COMSOL Multiphysics codes used in this study will be available upon request.

References

Qiu, B. et al. Nanofiber self-consistent additive manufacturing process for 3D microfluidics. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 8, 102 (2022).

Zhang, N. et al. 3D printing of micro-nano devices and their applications. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 11, 35 (2025).

Zaccagnini, P. et al. Laser-Induced Graphenization of PDMS as Flexible Electrode for Microsupercapacitors. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 8, 2101046 (2021).

Stang, M. et al. Embedded 3d printing of thermally-cured thermoset elastomers and the interdependence of rheology and machine pathing. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2200984 (2023).

Yang, Y. et al. 3D-Printed biomimetic super-hydrophobic structure for microdroplet manipulation and oil/water separation. Adv. Mater. 30, 1–11 (2018).

Kotikian, A., Truby, R. L., Boley, J. W., White, T. J. & Lewis, J. A. 3D Printing of liquid crystal elastomeric actuators with spatially programed nematic order. Adv. Mater. 30, 1–6 (2018).

Wang, Z. et al. Three-dimensional printing of functionally graded liquid crystal elastomer. Sci. Adv. 6, eabc0034 (2020).

Skylar-Scott, M. A., Mueller, J., Visser, C. W. & Lewis, J. A. Voxelated soft matter via multimaterial multinozzle 3D printing. Nature 575, 330–335 (2019).

Pongwisuthiruchte, A., Aumnate, C. & Potiyaraj, P. Tailoring of silicone urethane methacrylate resin for vat photopolymerization-based 3D printing of shape memory polymers. ACS Omega 9, 2884–2895 (2024).

Muth, J. T. et al. Embedded 3D printing of strain sensors within highly stretchable elastomers. Adv. Mater. 26, 6307–6312 (2014).

Zhou, L. Y. et al. Three-dimensional printed wearable sensors with liquid metals for detecting the pose of snakelike soft robots. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 23208–23217 (2018).

Kuang, X. et al. Grayscale digital light processing 3D printing for highly functionally graded materials. Sci. Adv. 5, 1–10 (2019).

Zhu, G., Hou, Y., Xu, J. & Zhao, N. Reprintable polymers for digital light processing 3D printing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 1–7 (2021).

Patel, D. K. et al. Highly stretchable and UV curable elastomers for digital light processing based 3D printing. Adv. Mater. 29, 1–7 (2017).

An, H. S. et al. High-resolution 3D printing of freeform, transparent displays in ambient air. Adv. Sci. 6, 1–8 (2019).

Walker, D. A., Hedrick, J. L. & Mirkin, C. A. Rapid, large-volume, thermally controlled 3D printingusing a mobile liquid interface. Science 366, 360–364 (2019).

Shinde, V. V., Celestine, A. D., Beckingham, L. E. & Beckingham, B. S. Stereolithography 3D printing of microcapsule catalyst-based self-healing composites. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2, 5048–5057 (2020).

Kotz, F. et al. Three-dimensional printing of transparent fused silica glass. Nature 544, 337–339 (2017).

Bhattacharjee, N., Parra-Cabrera, C., Kim, Y. T., Kuo, A. P. & Folch, A. Desktop-stereolithography 3D-printing of a poly (dimethylsiloxane)-based material with sylgard-184 properties. Adv. Mater. 30, 1800001 (2018).

Hinton, T. J., Hudson, A., Pusch, K., Lee, A. & Feinberg, A. W. 3D printing PDMS elastomer in a hydrophilic support bath via freeform reversible embedding. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2, 1781–1786 (2016).

O’Bryan, C. S. et al. Self-assembled micro-organogels for 3D printing silicone structures. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602800 (2017).

Bhattacharjee, T. et al. Writing in the granular gel medium. Sci. Adv. 1, 1–7 (2015).

Zhao, J. & He, N. A mini-review of embedded 3D printing: Supporting media and strategies. J. Mater. Chem. B 8, 10474–10486 (2020).

Robertson, I. D. et al. Rapid energy-efficient manufacturing of polymers and composites via frontal polymerization. Nature 557, 223–227 (2018).

Ziaee, M., Johnson, J. W. & Yourdkhani, M. 3D printing of short-carbon-fiber-reinforced thermoset polymer composites via frontal polymerization. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 16694–16702 (2022).

Sun, Y. et al. 3D printing of thermosets with diverse rheological and functional applicabilities. Nat. Commun. 14, 245 (2023).

Wang, B., Zhang, Z., Pei, Z., Qiu, J. & Wang, S. Current progress on the 3D printing of thermosets. Adv. Compos. Hybrid. Mater. 3, 462–472 (2020).

Lei, D. et al. A general strategy of 3D printing thermosets for diverse applications. Mater. Horiz. 6, 394–404 (2019).

Ozbolat, V. et al. 3D Printing of PDMS improves its mechanical and cell adhesion properties. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 4, 682–693 (2018).

Joseph Fortenbaugh, R. & Lear, B. J. On-demand curing of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) using the photothermal effect of gold nanoparticles. Nanoscale 9, 8555–8559 (2017).

Haas, K. M. & Lear, B. J. Billion-fold rate enhancement of urethane polymerization via the photothermal effect of plasmonic gold nanoparticles. Chem. Sci. 6, 6462–6467 (2015).

Habibi, M., Foroughi, S., Karamzadeh, V. & Packirisamy, M. Direct sound printing. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–11 (2022).

Packirisamy, M. & Habibi, M. Methods And Systems For Additive Manufacturing. https://patents.google.com/patent/CA3090684A1/en (2020).

Habibi, M., Packirisamy, M. & Foroughi, S. Ultra Active Micro-reactor Based Additive Manufacturing. https://patents.google.com/patent/US20230339181A1/en (2023).

Suslick, K. S., Eddingsaas, N. C., Flannigan, D. J., Hopkins, S. D. & Xu, H. The chemical history of a bubble. Acc. Chem. Res. 51, 2169–2178 (2018).

Didenko, Y. T. & Suslick, K. S. The energy efficiency of formation of photons, radicals and ions during single-bubble cavitation. Nature 418, 394–397 (2002).

Flint, E. B., Suslick, K. S., Series, N. & Sep, N. The temperature of cavitation. Icarus 253, 1397–1399 (2007).

Suslick, K. S. & Flannigan, D. J. Inside a collapsing bubble: sonoluminescence and the conditions during cavitation. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 59, 659–683 (2008).

Suslick, K. S., Eddingsaas, N. C., Flannigan, D. J., Hopkins, S. D. & Xu, H. Extreme conditions during multibubble cavitation: sonoluminescence as a spectroscopic probe. Ultrason. Sonochem. 18, 842–846 (2011).

Suslick, K. S. Sonochemistry. Science 247, 1439–1445 (1990).

Chatel, G. How sonochemistry contributes to green chemistry?. Ultrason. Sonochem. 40, 117–122 (2018).

Manickam, S. et al. Ultrasonics and sonochemistry: editors’ perspective. Ultrason. Sonochem. 99, 106540 (2023).

Kuang, X. et al. Self-enhancing sono-inks enable deep-penetration acoustic volumetric printing. Science 382, 1148–1155 (2023).

Debbi, L. et al. Ultrasound mediated polymerization for cell delivery, drug delivery, and 3D printing. Small Methods 8, 1–11 (2024).

Davoodi, E. et al. Imaging- guided deep tissue in vivo sound printing. Science 388, 616–623 (2025).

Yao, G. et al. Sound continuous production of thermosets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2312736, 1–11 (2023).

Weber, M., Hyvönen, J., Salmi, A. & Hæggström, E. Desktop direct sound 3D printing. In 2023 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS), 1−4 (IEEE, 2023).

Derayatifar, M., Habibi, M., Bhat, R. & Packirisamy, M. Holographic direct sound printing. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–14 (2024).

Yao, G. et al. Sound continuous production of thermosets. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 1–11 (2024).

Habibi, M., Foroughi, S., Karamzadeh, V. & Packirisamy, M. Supplementary information direct sound printing. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–26 (2022).

Mohammadamini, F., Rahbar Shahrouzi, J. & Samadi, M. A suspended polymeric microfluidic sensor for liquid flow rate measurement in microchannels. Sci. Rep. 12, 1–10 (2022).

Courson, R. et al. Rapid prototyping of a polymer MEMS droplet dispenser by laser-assisted 3D printing. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 85 (2023).

Park, J. et al. Real-time measurement of the contractile forces of self-organized cardiomyocytes on hybrid biopolymer microcantilevers. Anal. Chem. 77, 6571–6580 (2005).

Huang, J., Holt, R. G., Cleveland, R. O. & Roy, R. A. Experimental validation of a tractable numerical model for focused ultrasound heating in flow-through tissue phantoms. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 116, 2451–2458 (2004).

Acknowledgements

S.F. acknowledges the support of FRQNT (Fonds de Recherche du Québec, Canada) for providing the doctoral scholarship. The authors acknowledge the financial support from NSERC Discovery, Concordia Research Chair and PSO grants of M.P.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.F., M.H. and M.P. conceived the idea and designed the experiments and modeling. S.F. and M.H. implemented theoretical investigation, simulation, and testing, M.H. and M.P. supervised the work. S.F. and M.H. wrote the manuscript, M.P. edited the manuscript and all authors contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interests: M.H. and M.P. are inventors of patents (US20200001533A1). M.H., M.P. and S.F. are inventors of patents (US20230339181A1 and US Appl. NO. 63/500,681). These patents are related to the topic covered in this manuscript.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Foroughi, S., Habibi, M. & Packirisamy, M. Proximal sound printing: direct 3D printing of microstructures on polymers. Microsyst Nanoeng 12, 12 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01035-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41378-025-01035-w