Abstract

The nested variant of urothelial carcinoma, a frequent mimic of benign lesions on limited specimens, has been associated with high-stage disease including metastases at presentation. While PAX8 immunohistochemistry has been noted to be infrequently present in urothelial carcinoma in general, it has not been studied specifically in a cohort of nested urothelial carcinomas. Furthermore, TERT promoter mutation status is a potentially valuable biomarker for diagnosis of urothelial carcinoma and for noninvasive disease monitoring that has been observed in a majority of urothelial carcinoma and has previously been seen to be prevalent in multiple variant morphologies of urothelial carcinoma, including the nested variant. Twenty-five primary and three metastatic samples of nested urothelial carcinoma, along with 16 benign cases, were identified in a multicenter retrospective record review. PAX8 immunohistochemical stain was performed on all cases. In addition, TERT mutation analysis by allele-specific PCR was performed on 21 of the primary nested urothelial carcinoma cases and all benign cases. Positive PAX8 expression was identified in 52% (13 of 25) primary cases and 67% (2 of 3) metastatic cases of nested urothelial carcinoma; 50% (1 of 2) cases of large nested urothelial carcinoma were positive for PAX8. PAX8 expression was negative in the benign urothelium in all cases. TERT promoter mutation was observed in 83% (15 of 18) nested urothelial carcinoma cases and in 6% (1 of 16) of the benign cases. Recognition of the prevalence of positive PAX8 staining in this clinically relevant variant of urothelial carcinoma is essential to avoiding inaccurate or delayed diagnosis during the diagnostic workup of bladder lesions suspicious for nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Moreover, the prevalence of TERT promoter mutations in nested urothelial carcinoma is similar to that of conventional urothelial carcinoma, further supporting its use as a biomarker that is stable across morphologic variants of urothelial carcinoma.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The nested variant of urothelial carcinoma is relatively uncommon [1], and is architecturally defined by infiltrating, variably sized nests with branches and/or anastomoses. The cytologic features are characteristically bland, with minimal atypia, especially in superficial portions of tumors [2,3,4,5,6]. When combined with its cytologic banality, a minimal elicited stromal response can lead to mischaracterization of these lesions on limited specimens as florid proliferation of von Brunn nests, cystitis cystica, inverted noninvasive low-grade papillary urothelial carcinoma, or, in the presence of focal tubular differentiation, nephrogenic adenoma [5, 7]. Crucially, nested urothelial carcinoma in pure form or as a mixed component of conventional urothelial carcinoma is associated with high-stage disease and the presence of metastases at presentation [6, 8, 9].

In the largest cohorts of nested urothelial carcinoma previously studied, the immunohistochemical profile of nested urothelial carcinoma has been shown to exhibit relative similarity to conventional urothelial carcinoma [6]. However, the authors of this study have anecdotally observed a disproportionately high incidence of PAX8 staining in nested urothelial carcinoma cases. Previous studies have shown a rate of PAX8 positivity of 7–18% in urothelial carcinoma in general [10,11,12,13]. Studies that delineate upper genitourinary tract and lower tract urothelial carcinoma from one another have demonstrated possible enrichment of expression in upper tract cases (9–24% PAX8 positive) compared with lower tract cases (0–18% PAX8 positive) [10,11,12,13,14,15]. However, to our knowledge, PAX8 expression has not yet been assessed in a substantial cohort of nested urothelial carcinoma. An accurate assessment of PAX8 expression in nested urothelial carcinoma is essential to help avoid diagnostic pitfalls during the workup of primary and metastatic lesions for which common PAX8 positive lesions may be included in the differential diagnosis.

Moreover, mutations in the telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter, which are present in 60–80% of urothelial carcinomas [16, 17], have been shown previously by some of our coauthors to be a stable biomarker that is often conserved in temporally, spatially, and morphologically distinct components in urothelial carcinoma [18]. No examples of the nested variant were explicitly represented in this cohort; however, previous work by Zhong et al. [19] identified TERT promoter mutations in 85% of 20 cases of nested urothelial carcinoma and 80% of 10 cases of large nested urothelial carcinoma using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-sequencing method. TERT promoter mutations were also found to be specific for urothelial carcinoma and were not detected in benign mimics of urothelial carcinoma like von Brunn nests, cystitis cystica, cystitis glandularis, or nephrogenic adenoma [19]. We sought to determine the prevalence of TERT promoter mutation in nested urothelial carcinoma using allele-specific PCR methodology [18]. Given the potential future importance of TERT promoter mutations as (a) biomarkers monitoring for recurrence, including in urine specimens [20, 21], (b) distinguishing nested urothelial carcinoma from benign mimics [19], and (c) identifying urothelial origin in metastatic lesions, it is important to continue to reinforce the prevalence of mutation status within this variant as well as to validate assays that sensitively identify these variants; we also sought to identify a relationship, if present, between PAX8 expression and results of TERT promoter mutation status.

With these aims, in this study we present the results and potential clinical implications of PAX8 expression and TERT promoter mutation analysis on a cohort of 25 primary and 3 metastatic cases of nested urothelial carcinoma.

Materials and methods

Study cohort

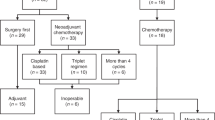

A collaborative effort of multiple major academic medical centers identified examples of nested urothelial carcinoma through retrospective review of surgical pathology records. Patient samples were procured from the University of Michigan Health System, Cleveland Clinic, and Emory University School of Medicine; this study was performed under Institutional Review Board—approved protocols (with waiver of informed consent). Multiple reviewers including genitourinary pathologists (JKM, AOO, and RM) and one pathology resident (AT) diagnosed and/or rereviewed hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stained slides to confirm the diagnosis of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma with classic features (as described above, Fig. 1a–c), in 25 primary and 3 metastatic cases from 26 patients. In two primary cases, the variant morphology was characterized as “large nested” (Fig. 1c). In the 2016 revision to the World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs, the large nested variant falls within the definition of the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma, which now includes cases with small-to-large-sized nests [22]. The large nested variant has been characterized with similar clinical and immunophenotypic features to the nested variant [23, 24]. For these reasons, these two cases were considered to be appropriate for inclusion in our cohort. For two patients, both a primary nested urothelial carcinoma and concurrent nodal metastasis were available for interrogation. In addition, 16 benign cases were collected to compare potential benign mimics; this group included nephrogenic adenoma (4), proliferative von Brunn nests (4), cystitis cystica et glandularis, and other cases of proliferative and polypoid cystitis.

a, b (Hematoxylin and eosin, ×10) show round to slightly angulated nests and cords of cells with round, low-grade-appearing nuclei (inset of b at ×40) of high-power magnification. c Large nested urothelial carcinoma (×10). Show range of PAX8 staining, which was either graded as strongly positive (d, ×20) with definitive nuclear staining in a majority of cells, focally positive (e, ×20) with nuclear staining present but varying in prevalence/intensity throughout and between tumor nests, or negative (f, ×40) with a cytoplasmic blush and no nuclear staining. PAX8 expression was negative in overlying urothelium (d).

PAX8 immunohistochemistry

Four-micron sections of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were deparaffinized, and heat-induced epitope retrieval was performed on the Ventana BenchMark ULTRA immunostainer using CC1 Cell Conditioning solution (Ventana Medical System, Tuscon, AZ, USA). After blocking endogenous peroxidase activity, the slides were incubated for 32 min at 37 °C with PAX8 rabbit polyclonal primary antibody (predilute; Cell Marque [catalog #363A-18], Rocklin, CA, USA) and subsequently detected by using the ultraView DAB detection system (Ventana Medical System).

PAX8 immunohistochemical expression in nested urothelial carcinoma areas was graded by two aforementioned reviewers (AT and RM) according to a 0–4 scoring system (0 = absent staining, 1 = weak staining, 2 = moderate staining, 3 = strong staining) and the percent of cells with positive staining was estimated. While reviewing PAX8 staining results, three discrete patterns of expression were recognized and all cases fit readily into these categories; for this reason, we revised and simplified our scoring criteria to include the following categories: “strongly positive” (Fig. 1d) in which bright nuclear staining was identified in the majority of cells; “focally positive” (Fig. 1e) in which unequivocal nuclear staining was present but in variable intensity and variable proportions of cells; and “negative” (Fig. 1f) in which tumor nests demonstrated a cytoplasmic blush but no definitive nuclear staining was identified.

TERT promoter mutation analysis

We previously developed [18] an allele-specific PCR assay targeting the most common TERT promoter mutations: c.-146C>T (Chr.5:1295250C>T), c.-124C>T (Chr.5:1295228C>T), c.-138_139CC>TT (Chr.5:1295 242_1295243CC>TT), and c.-124_125CC>TT (Chr.5: 1295228_1295229CC>TT). This assay was performed on DNA samples extracted from areas of microdissected nested urothelial carcinoma (isolating the invasive nested component specifically) in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissue in 21 cases of nested urothelial carcinoma from our cohort as well as the 16 benign cases. Five cases of nested urothelial carcinoma did not undergo TERT promoter mutation testing as corresponding tissue blocks were not available for molecular interrogation at the time of this analysis.

Results

Clinical and pathologic characteristics of the study cohort

The clinical and pathologic characteristics of the study cohort are delineated in Table 1. The cohort was composed of 26 patients, 21 (81%) males and 5 (19%) females with a mean age of 67 years. All cases of nested urothelial carcinoma in this cohort were from the urinary bladder. The cohort was comprised of 12 (46%) transurethral resections (TURBT) specimens, 13 (50%) surgical resection specimens, and one cutaneous excision of a metastatic lesion. The pathologic T-stage of the resection specimens ranged from pT1 to pT4a, and the pathologic nodal stage ranged from N0 to N3. Nested features were “pure” (no other differentiation observed) in 14 (54%) cases, “extensive” (greater than 50% but with the presence of some conventional urothelial carcinoma) in 5 (19%) cases, and focal (less than 50% with the presence of conventional urothelial carcinoma) in 7 (27%) cases.

PAX8 immunohistochemistry results

PAX8 positivity was identified in 54% (14 of 26) of nested urothelial carcinoma cases, and specifically in 52% (13 of 25) of primary cases and 67% (2 of 3) of metastatic cases (Fig. 2). Of these positive cases, ten were considered strongly positive and four were considered focally positive; there was no relationship between the extent of PAX8 positivity (focal versus diffuse) and the purity of nested features. In the seven cases of focally nested urothelial carcinoma with adjacent conventional urothelial carcinoma, PAX8 expression within the conventional component was concordant with that of the expression within the nested component in all seven cases; 57% (four of seven) had positive PAX8 in both the conventional and nested components. Of the two primary cases of large nested urothelial carcinoma within the cohort, one was focally positive for PAX8 expression and the other one was negative. Clinicopathologic features of the cohort compared between PAX8 positive and negative groups are delineated in Table 1. Amongst the cases of nested urothelial carcinoma evaluated, overlying uninvolved urothelial mucosa was available for histologic interrogation in 60% of cases (15/25) with negative PAX8 expression in the benign urothelium of all cases (0/15). Within the benign comparison group, PAX8 was strongly positive in all cases of nephrogenic adenoma (4/4), and negative in all cases of proliferative von Brunn nests (0/4), cystitis cystica et glandularis (0/1), and other cases of proliferative cystitis (0/7).

TERT promoter mutation results

Three nested urothelial carcinoma cases were inadequate because of small tumor area/volume on the available slide/block. Of the remaining cases, TERT promoter mutations were identified in 83% (15 of 18) of nested urothelial carcinoma cases, with the remaining three cases confirmed as wild type (WT) alleles. Of the 15 TERT mutated cases, 11 cases harbored a −125C>T mutation and 4 cases harbored a −146C>T mutation. When separated by PAX8 expression by immunohistochemistry, TERT promoter mutations were observed in 89% (eight of nine) of successfully tested PAX8 positive cases and 78% (seven of nine) of successfully tested PAX8-negative cases, with no statistically significant difference between these two subgroups (p = 0.53 via Chi-Square test). TERT promoter mutations were observed in 91% (10 of 11) of cases with pure nested features, 80% (4 of 5) of cases with extensive nested features, and 50% (1 of 2) of cases with focal nested features, with no statistically significant difference (p = 0.35). In the benign comparison group of nephrogenic adenoma, proliferative von Brunn nests, and proliferative cystitis there was a TERT promoter mutation detected in 1 of 16 cases (6%). The single-morphologically benign case harboring a −146C>T TERT promoter mutation was a cystectomy for neurogenic urinary bladder dysfunction; histologic reexamination was consistent with the previously rendered diagnosis of polypoid cystitis.

Discussion

The paired box (PAX) genes encode transcription factors crucial in determination and differentiation of cell lineage during and after embryonic development; [25] PAX8 specifically is relatively nephric-lineage specific and is considered to be an essential transcription factor for organogenesis of the kidney, Müllerian system, and thyroid gland. While PAX8 has been previously shown in the literature to be expressed in a high percentage of cortical carcinomas of the kidney (~90%), endometrium (~90%), ovary (~80%), and thyroid (~50%), it is considered to be expressed only in a minority of urothelial carcinomas, with a relative enrichment of expression amongst tumors originating within the upper urinary tract [11,12,13,14,15]. PAX8 is also now well known to be expressed in normal Wolffian duct-derived epithelium and in tumors of both Wolffian-type and Müllerian-type epithelium in the male genital tract [26, 27], as well as in the majority of nephrogenic adenoma and clear cell adenocarcinoma of the lower urinary tract; PAX8 expression is generally not detected in prostatic adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder, though not all morphologic variants have been extensively studied [28]. Our cohort of 25 primary and 3 metastatic cases of lower tract nested urothelial carcinoma demonstrated PAX8 positivity in more than half of cases, suggesting that this staining pattern could present more of a diagnostic pitfall than previously understood. Interestingly, PAX8 expression was negative in benign urothelium adjacent to nested urothelial carcinoma (0/15 cases), suggesting PAX8 to be aberrantly expressed in this variant of urothelial carcinoma.

First, our study expands the immunophenotypic expression patterns which might be observed within the histologic variants of urothelial carcinoma. The nested variant of urothelial carcinoma, which often presents as a locally advanced tumor, is thought to demonstrate an immunophenotype very similar to conventional invasive urothelial carcinoma (or not-otherwise-specified [NOS] type), previously established to have frequent expression of GATA3, TP63, high molecular weight cytokeratin, and only rare expression of PAX8. However, our data here demonstrate that ~50% of the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma cases demonstrate PAX8 expression. From a clinicopathologic perspective, no statistically significant differences between PAX8 positive and PAX8 negative groups were observed in pathologic tumor or node stage of the nested urothelial carcinoma cases within this cohort.

Second, given the morphologic overlap between nested urothelial carcinoma and benign mimics including nephrogenic adenoma, the results of our study urge caution regarding the use of PAX8 in differentiating these lesions. Previous investigations from our group and others have demonstrated nephrogenic adenoma to be relatively common lesions within the genitourinary tract that often mimic malignancy, including the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Nephrogenic adenoma has been previously shown to be variably positive for PAX8, GATA3, and AMACR with predominantly negative TP63 and NKX3.1 expression [29, 30], and in this study’s benign comparator group, PAX8 expression was strongly positive in all four cases of nephrogenic adenoma. Urothelial carcinomas have previously been considered to be negative for PAX8 expression except in a minority of cases, thus helping resolve the differential diagnosis from nephrogenic adenoma. The findings from our study indicate that a substantial proportion of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma can demonstrate PAX8 expression, which limits the utility of this immunohistochemical marker in this clinical scenario. Instead, morphologic assessment as well as other correlative immunohistochemical assessment (for TP63) and assessment of TERT promoter mutation status, shown to be positive in the majority of nested variant of urothelial carcinoma and negative in nephrogenic adenoma, might be more useful assays in the diagnostic algorithm, when necessary.

Finally, our results also provide impetus for careful attention when using PAX8 expression in the workup of metastatic carcinoma of unknown primary. PAX8 is widely used as a lineage marker during workup of metastasis for its high sensitivity for carcinomas arising from the kidney, ovary, and thyroid [31]. The possibility of a urothelial primary should be considered if evaluating a metastatic carcinoma in the presence of a known renal, ureteral, or urinary bladder mass. While nuclear pleomorphism, stromal desmoplasia, or unusual architectural patterns (e.g., micropapillary) are possible clues to urothelial origin, the coexpression of TP63, HMWCK, and/or GATA3 adds further support for urothelial lineage in this setting [32]. In the presence of a tumor which demonstrates both PAX8 and TP63 expression at a metastatic site, in general an upper urinary tract primary is favored over lower urinary tract as the site of origin. The results from our study demonstrate that approximately half of the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma cases may demonstrate positive PAX8 expression, including expression at metastatic sites. Given the aggressive clinical outcomes and including metastatic potential of the nested variant urothelial carcinoma, it is important to keep this in perspective while working up metastatic tumors with unknown primaries.

The diagnostic conundrums described above could be partially mitigated by morphologic evaluation supported by assessment of TERT promoter mutation status, which are common in urothelial carcinoma and comparably uncommon in many other common metastatic malignancies [33]. Our reinforcement of work by Zhong et al. [19] that TERT promoter mutations are present in >80% of nested urothelial carcinoma suggest that this tool may be used to differentiate nested urothelial carcinoma from benign mimics as well as many nonurothelial malignancies in cases for which morphologic assessment alone is nonconclusive. Notably, in our benign comparison group, one case of polypoid cystitis (a cystectomy performed for neurogenic urinary bladder dysfunction) harbored a TERT promoter mutation; neurogenic urinary bladder dysfunction is a known risk factor for the development of urothelial carcinoma [34, 35], and it is possible in this case that the molecular signature of neoplasia preceded any detectable morphologic changes. In nested urothelial carcinoma, TERT promoter mutation status was not significantly correlated with PAX8 expression status by immunohistochemistry. The continued development, validation, and investigation into the clinical use of this and similar assays for identifying TERT promoter mutations may contribute to new tools to help identify origins of metastatic lesions when morphology and immunohistochemistry are equivocal or potentially misleading.

While this study is limited by its focus on histologic, molecular, and immunohistochemical features, the results are diagnostically important for pathologists. We did not observe an association between PAX8 expression and other clinicopathologic features in nested urothelial carcinoma, and larger cohorts will be needed to address any potential impact of PAX8 expression in this context. Also, because of its rarity, we were unable to include any nested urothelial carcinoma cases from the upper urinary tract in the current study. Nevertheless, recognition of the prevalence of positive PAX8 staining in nested urothelial carcinoma is essential for workup of primary or metastatic lesions for which morphologic features are inconclusive. Future work may continue to evaluate immunophenotypic patterns in variant morphologies of urothelial carcinoma as well as evaluate the clinical integration of TERT promoter mutation testing into diagnostic workflows.

References

Shah RB, Montgomery JS, Montie JE, Kunju LP. Variant (divergent) histologic differentiation in urothelial carcinoma is under-recognized in community practice: impact of mandatory central pathology review at a large referral hospital. Urol Oncol. 2013;31:1650–5.

Dhall D, Al-Ahmadie H, Olgac S. Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1725–7.

Drew PA, Furman J, Civantos F, Murphy WM. The nested variant of transitional cell carcinoma: an aggressive neoplasm with innocuous histology. Mod Pathol. 1996;9:989–94.

Murphy WM, Deana DG. The nested variant of transitional cell carcinoma: a neoplasm resembling proliferation of Brunn’s nests. Mod Pathol. 1992;5:240–3.

Volmar KE, Chan TY, De Marzo AM, Epstein JI. Florid von Brunn nests mimicking urothelial carcinoma: a morphologic and immunohistochemical comparison to the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:1243–52.

Wasco MJ, Daignault S, Bradley D, Shah RB. Nested variant of urothelial carcinoma: a clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 30 pure and mixed cases. Hum Pathol. 2010;41:163–71.

Kunju LP. Nephrogenic adenoma: report of a case and review of morphologic mimics. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1455–9.

Beltran AL, Cheng L, Montironi R, et al. Clinicopathological characteristics and outcome of nested carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Virchows Arch. 2014;465:199–205.

Linder BJ, Frank I, Cheville JC, et al. Outcomes following radical cystectomy for nested variant of urothelial carcinoma: a matched cohort analysis. J Urol. 2013;189:1670–5.

Gailey MP, Bellizzi AM. Immunohistochemistry for the novel markers glypican 3, PAX8, and p40 (DeltaNp63) in squamous cell and urothelial carcinoma. Am J Clin Pathol. 2013;140:872–80.

Laury AR, Perets R, Piao H, et al. A comprehensive analysis of PAX8 expression in human epithelial tumors. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:816–26.

Tacha D, Zhou D, Cheng L. Expression of PAX8 in normal and neoplastic tissues: a comprehensive immunohistochemical study. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2011;19:293–9.

Tong GX, Yu WM, Beaubier NT, et al. Expression of PAX8 in normal and neoplastic renal tissues: an immunohistochemical study. Mod Pathol. 2009;22:1218–27.

Albadine R, Schultz L, Illei P, et al. PAX8 (+)/p63 (−) immunostaining pattern in renal collecting duct carcinoma (CDC): a useful immunoprofile in the differential diagnosis of CDC versus urothelial carcinoma of upper urinary tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34:965–9.

Gonzalez-Roibon N, Albadine R, Sharma R, et al. The role of GATA binding protein 3 in the differential diagnosis of collecting duct and upper tract urothelial carcinomas. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2651–7.

Kinde I, Munari E, Faraj SF, et al. TERT promoter mutations occur early in urothelial neoplasia and are biomarkers of early disease and disease recurrence in urine. Cancer Res. 2013;73:7162–7.

Kurtis B, Zhuge J, Ojaimi C, et al. Recurrent TERT promoter mutations in urothelial carcinoma and potential clinical applications. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2016;21:7–11.

Brown NA, Lew M, Weigelin HC, et al. Comparative study of TERT promoter mutation status within spatially, temporally and morphologically distinct components of urothelial carcinoma. Histopathology. 2018;72:354–6.

Zhong M, Tian W, Zhuge J, et al. Distinguishing nested variants of urothelial carcinoma from benign mimickers by TERT promoter mutation. Am J Surg Pathol. 2015;39:127–31.

Springer SU, Chen C-H, Rodriguez Pena MDC, et al. Non-invasive detection of urothelial cancer through the analysis of driver gene mutations and aneuploidy. Elife. 2018;7:e32143.

Ward DG, Baxter L, Gordon NS, et al. Multiplex PCR and next generation sequencing for the non-invasive detection of bladder cancer. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0149756.

Humphrey PA, Moch H, Cubilla AL, Ulbright TM, Reuter VE. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs-part B: prostate and bladder tumours. Eur Urol. 2016;70:106–19.

Comperat E, McKenney JK, Hartmann A, et al. Large nested variant of urothelial carcinoma: a clinicopathological study of 36 cases. Histopathology. 2017;71:703–10.

Cox R, Epstein JI. Large nested variant of urothelial carcinoma: 23 cases mimicking von Brunn nests and inverted growth pattern of noninvasive papillary urothelial carcinoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1337–42.

Blake JA, Ziman MR. Pax genes: regulators of lineage specification and progenitor cell maintenance. Development. 2014;141:737–51.

Magers MJ, Udager AM, Chinnaiyan AM, et al. Comprehensive immunophenotypic characterization of adult and fetal testes, the excretory duct system, and testicular and epididymal appendages. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2016;24:e50–68.

Tong GX, Memeo L, Colarossi C, et al. PAX8 and PAX2 immunostaining facilitates the diagnosis of primary epithelial neoplasms of the male genital tract. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1473–83.

Tong GX, Weeden EM, Hamele-Bena D, et al. Expression of PAX8 in nephrogenic adenoma and clear cell adenocarcinoma of the lower urinary tract: evidence of related histogenesis? Am J Surg Pathol. 2008;32:1380–7.

McDaniel AS, Chinnaiyan AM, Siddiqui J, McKenney JK, Mehra R. Immunohistochemical staining characteristics of nephrogenic adenoma using the PIN-4 cocktail (p63, AMACR, and CK903) and GATA-3. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:1664–71.

Zhang G, McDaniel AS, Mehra R, McKenney JK. Nephrogenic adenoma does not express NKX3.1. Histopathology. 2017;71:669–71.

Conner JR, Hornick JL. Metastatic carcinoma of unknown primary: diagnostic approach using immunohistochemistry. Adv Anat Pathol. 2015;22:149–67.

Cox RM, Magi-Galluzzi C, McKenney JK. Immunohistochemical pitfalls in genitourinary pathology: 2018 update. Adv Anat Pathol. 2018;25:387–99.

Killela PJ, Reitman ZJ, Jiao Y, et al. TERT promoter mutations occur frequently in gliomas and a subset of tumors derived from cells with low rates of self-renewal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:6021–6.

Bothig R, Kurze I, Fiebag K, et al. Clinical characteristics of bladder cancer in patients with spinal cord injury: the experience from a single centre. Int Urol Nephrol. 2017;49:983–94.

Kalisvaart JF, Katsumi HK, Ronningen LD, Hovey RM. Bladder cancer in spinal cord injury patients. Spinal Cord. 2010;48:257–61.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Taylor, A.S., McKenney, J.K., Osunkoya, A.O. et al. PAX8 expression and TERT promoter mutations in the nested variant of urothelial carcinoma: a clinicopathologic study with immunohistochemical and molecular correlates. Mod Pathol 33, 1165–1171 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0453-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-020-0453-z

This article is cited by

-

Das muskelinvasive und metastasierte Urothelkarzinom der Harnblase

Die Pathologie (2024)

-

Nachahmerläsionen/diagnostische Fallstricke des Harnblasenkarzinoms

Die Pathologie (2024)

-

Morphology, immunohistochemistry characteristics, and clinical presentation of microcystic urothelial carcinoma: a series of 10 cases

Diagnostic Pathology (2023)

-

Advances in bladder cancer biology and therapy

Nature Reviews Cancer (2021)

-

Telomerase reverse transcriptase (TERT) promoter mutations in primary adenocarcinoma of bladder and urothelial carcinoma with glandular differentiation: pathogenesis and diagnostic implications

Modern Pathology (2021)