Abstract

Renal oncocytoma is the most common benign epithelial renal neoplasm. Several adverse features that would typically increase the stage of renal cell carcinomas are not uncommon in renal oncocytoma, including perinephric, sinus fat, or renal vein invasion. Herein, we report the largest single institutional series of renal oncocytoma with adverse pathologic features. The cohort comprised 50 patients, 38 were men (76%) and 12 were women (24%), with a mean age of 68 years (range, 50–87 years). All cases were diagnosed on nephrectomy specimens. No laterality predilection was noted. The tumors ranged in size from 1.5–15.7 cm (mean, 5.3 cm). Adverse pathologic features included perinephric fat invasion (n = 25; 50%), renal sinus fat invasion (n = 9; 18%), and renal vein invasion (n = 5; 10%). More than one adverse feature was seen in 11 tumors (22%). All tumors showed diffuse reactions to KIT (n = 40; 100%) and cyclin D1 (n = 27; 100%). Keratin 7 highlighted rare (<5%) scattered cells, as well as entrapped renal tubules (n = 21; 100%). Reaction to DOG1 was patchy in three tumors (n = 27; 11%) while reactions to vimentin (n = 31) and Hale colloidal iron special stain (n = 30) were negative. On follow-up, no tumor recurrence or metastasis was observed over a follow-up range of 1–144 months (mean, 54 months; median, 60 months). Our data suggest that adverse pathologic features in renal oncocytoma do not alter their benign course.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Renal oncocytoma, first described by Zippel in 1942 and further elucidated by Klein and Valensi in 1976, is a common renal epithelial tumor [1, 2]. It accounts for 5–9% of all renal neoplasms and occurs over a wide age range at presentation (24–91 years) [3]. It is also known for its characteristic gross and microscopic appearances, which facilitate its recognition. Histologically, it is formed of nests of cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm, central nuclei, and inconspicuous nucleoli in an edematous stroma. Occasionally, one or more “adverse” pathologic features are present in otherwise typical cases, including peripheric fat, sinus fat, or vascular invasion [4]. These features would unequivocally upstage renal cell carcinomas and pose a higher risk of recurrence or metastasis. In this study, we reviewed the largest cohort of patients with renal oncocytoma that had “adverse” pathologic features and provided clinical outcome analysis of these cases.

Materials and methods

An electronic search of our institutional databases for cases of renal oncocytoma with documented one or more of the following adverse features––peripheric fat, sinus fat, or vascular invasion was performed. Cases were retrieved from pathology department files and hematoxylin and eosin-stained slides were reviewed to confirm the diagnosis and the presence of these features. Sections of 4 μm thickness were stained for Hale colloidal iron special stain and with antibodies directed against KIT (YR145; Cell Marque, Rocklin, CA), keratin 7 (OV-TL 12/30; Dako, Carpinteria, CA), vimentin (V9; Dako), DOG1 (SP31; Cell Marque), and cyclin D1 (EP12; DAKO) in a Dako automated instrument. Positive and negative controls gave appropriate results for each stain. This research was approved by the Institutional Review Board at Indiana University.

Results

Clinical features

The clinical findings were tabulated in Table 1. Renal oncocytoma with adverse pathologic features accounted for 5% of all renal oncocytomas diagnosed at our institution, excluding consultation cases. It occurred more frequently in males (n = 38; 76%) than in females (n = 12; 24%), with ages ranging from 50–87 years (mean, 68 years). No laterality predilection was noted (27 left-sided and 23 right-sided). All tumors were diagnosed on nephrectomy specimens (17 partial and 33 total nephrectomies). Four patients had end-stage renal disease. Six patients had multiple tumors (defined as ≥2 unilateral or bilateral tumors), ranging from 2–4 tumors, including one (no. 5) who had numerous oncocytic tumors and was diagnosed with renal oncocytosis, other tumors or malignancies diagnosed in the remaining five patients included cervical squamous cell carcinoma (no. 12), colonic and prostatic adenocarcinoma (no. 24), prostatic adenocarcinoma, contralateral clear cell renal cell carcinoma (no. 35), Hodgkin lymphoma (no. 46), and ductal carcinoma in situ of the breast (no. 48).

Pathologic and immunohistochemical features

Tumor sizes were available for 45 tumors and ranged from 1.5–15.7 cm (mean, 5.3 cm; median, 4.2 cm). Tumors were well-defined with solid mahogany brown cut surfaces. A characteristic central scar was present in 50% of cases. Two cases had gross extension into the renal sinus and renal vein (no. 9) and perinephric fat (no. 22). Both cases had positive tumor margins, while the margins were negative in all remaining tumors.

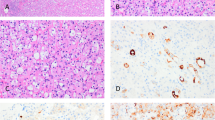

Architecturally, differing proportions of morphologic patterns were present in each case. Nested followed by solid-like growth patterns were the most common (Fig. 1A, B). The latter pattern was formed of tightly packed nests, seen frequently at the periphery of the tumor, with minimal intervening stroma. These were followed by a tubulocystic pattern, which was filled with pale eosinophilic secretions (Fig. 1C). Trabecular, anastomosing/branching nested, and rarely papillary-like patterns were less common. Entrapped renal tubules, mostly at the tumor periphery, were also seen in all tumors. The cells were polygonal to cuboidal with moderate to abundant dense eosinophilic and granular cytoplasm. A cellular discohesiveness between tumor cells was seen, at least focally, in all tumors (Fig. 1D).

Renal oncocytoma tumors are formed predominantly of solid (A), nested (B), and tubulocystic (C) architectures. Areas of cellular discohesiveness between tumor cells are seen (D). The stroma is only minimally present at the periphery (A) but is edematous and paucicellular centrally (C and D). The tumor shows minimal to mild nuclear pleomorphism with inconspicuous nucleoli occasionally seen (E). Focal “degenerative” atypia, nuclear hyperchromasia (F), and binucleation are seen (inset).

The stroma was edematous and paucicellular in the middle of most tumors; however, it was minimally present at the periphery, where only minimal intervening stroma containing compressed capillaries was present (Fig. 1B, C). Cytologically, all tumors were uninuclear, had minimal to mild nuclear pleomorphism, and occasionally inconspicuous nucleoli (Fig. 1E). Foci rare binucleation and trinucleation were seen in most cases with 8% (n = 4) showing moderate to marked “degenerative” atypia, nuclear hyperchromasia, and smudge chromatin (Fig. 1F). These appeared more common in the solid, compact-nested areas. Nonetheless, no mitotic figures, necrosis, or perinuclear halos were seen in any tumor.

Adverse pathologic features included perinephric fat invasion (n = 25; 50%), renal sinus fat invasion (n = 9; 18%), and renal vein invasion (n = 5; 10%). More than one adverse feature was seen in 11 tumors (22%), including perinephric fat and renal vein invasion (n = 4; 8%); sinus fat and renal vein invasion (n = 4; 8%); perinephric fat and sinus fat invasion (n = 2; 4%); and invasion of perinephric fat, sinus fat and renal vein (n = 1; 2%). Invasion into the perinephric and sinus fat was seen almost exclusively in the solid areas at the periphery of the tumor, in which small, compacted nests break through the tumor boundaries of about 1–2 mm. Although most tumors were well-circumscribed, nodules of tumor nests with prominent pushing-type invasion were noted in 12 cases (24%). In addition, invasion into the renal vein was grossly evident in one tumor. The invasion seen in the remaining tumors was of segmental branches of the renal vein (Fig. 2).

Tumors show extension into the peripheric and renal adipose tissue in the form of nests that extend for a short distance in most tumors (A and B) or solid detached nodules within the peripheric adipose tissue (C). The tumor extends into a major branch of the renal vein at the renal hilum (D) with adherence to the venous wall (D).

On immunohistochemical staining, all tumors showed diffuse reactions to antibodies for KIT (n = 40; 100%) and cyclin D1 (n = 27; 100%) (Fig. 3). Reactions to cyclin-D1 ranged from focal to diffuse (≤50% and >50% nuclear staining, respectively) in 12 and 15 tumors (45% and 55%), respectively. Keratin 7 highlighted rare (<5%) scattered cells, as well as entrapped renal tubules (100%), except in 2 tumors (n = 2/21; 10%) which showed rare foci of increased immunoreactivity in the central scar areas. Reaction to DOG1 was patchy in three tumors (3/27; 11%). Reaction to vimentin was consistently negative, except for four tumors which showed focal positive reaction around the central hyalinized area (4/31; 13%). Hale colloidal iron special stain was consistently negative (0/30; 0%).

Clinical follow-up and outcomes

On follow-up, survival data were available for all patients. All were alive, except three who died of other causes (patients nos. 24 [perinephric fat invasion] and 44 and 46 [both had renal sinus invasion]). Sufficient clinical follow-up was available for 28 patients, including 17 with isolated perinephric fat invasion, 6 with isolated renal sinus fat invasion, 2 with isolated renal vein invasion, 1 with renal vein and sinus fat invasion, 1 with renal vein and perinephric fat invasion, and 1 with perinephric and sinus fat invasion. No disease recurrence or metastasis occurred at a mean and median follow-up period of 54 and 60 months, respectively (range, 1–144 months).

Discussion

Renal oncocytoma is a common benign renal epithelial tumor. It accounts for 3–9% of all renal epithelial neoplasms [3]. It is thought to arise from the intercalated cells of the cortical collecting duct from the distal nephron. Renal oncocytoma mostly occurs in middle-aged to older patients and is more common in men [5]. In our series, the mean age at presentation was 68 years (range, 50–87 years).

Although it was first recognized in 1942, the emergence of renal oncocytoma as a unique entity was established in 1976 [1, 2]. Subsequent studies further characterized its histomorphologic features [6,7,8]. Histologically, the tumors formed nested, tubulocystic, or mixed patterns. A solid pattern created by closely compacted nests was also common. Cytologically, the cells had eosinophilic granular cytoplasm related to the abundant mitochondrial content. The nuclei were typically round, with well-defined contour. Areas of extensive necrosis, increased mitotic figures, sarcomatoid differentiation, or well-formed papillary growth were not features of oncocytoma and were considered potentially exclusionary [5, 8].

The diagnostic features of renal oncocytoma are straightforward in most cases. Pseudomalignant features, including invasion into the perinephric fat, renal sinus fat, or renal vein, were documented in multiple reports [9,10,11,12]. The incidence of these adverse pathologic features varied but reported highest for peripheric fat invasion and lowest for sinus fat invasion. A survey of urologic pathologists reported by Williamson et al found that up to 82% of the participants considered a single mitotic figure to be compatible with oncocytoma. Invasion of perinephric fat, sinus fat, and renal vein or a vein branch was found to be unequivocally compatible with the diagnosis of oncocytoma by 59%, 53%, and 35% of the participants, respectively [13].

The immunohistochemical profile of renal oncocytoma is consistent. Keratin 7 was one of the most widely used and helpful stains to confirm the diagnosis [14]. Similar to our findings, it normally stained isolated tumor cells (<5%). This threshold had the greatest acceptability rate among surveyed urologic pathologists [13]. Additional diagnostic markers, including KIT, cyclin D1, and DOG1, were reported. The latter had high sensitivity (100%) for the diagnosis of oncocytoma but had lower specificity [15, 16]. Negative immunoreactivity for vimentin was also among the frequently used markers when unusual morphologic features were encountered; however, a common pitfall when interpreting the results of keratin 7 and vimentin was observed around the areas of the central scar, where increased reactivity for both markers was not uncommon [12, 17]. Four tumors in our series had focal immunoreactivity to vimentin (n = 4/31; 13%) around the central scar area, while 2 (n = 2/21; 10%) showed rare foci of increased keratin 7 immunoreactivity.

Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma is the most important differential diagnosis, especially the eosinophilic variant. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma often grossly mimics oncocytoma with a well-circumscribed brown appearance that may contain a central scar as well. Microscopically, these tumors tend to be solid, nested, or trabecular in architecture, which overlaps with those seen in renal oncocytoma. However, in chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, the cells usually have sharply defined cell borders, perinuclear halos, irregular nuclei, wrinkled “raisinoid” nuclear contour, and more frequent binucleation and multinucleation. In the eosinophilic variant chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, the tumor is almost purely formed of smaller sized cells with finely eosinophilic and granular cytoplasm, similar to that seen in renal oncocytoma [18]. Immunohistochemically, chromophobe renal cell carcinoma has a positive reaction to KIT similar to renal oncocytoma; however, reaction for keratin 7 is diffusely positive, contrasting to renal oncocytoma. Although diminished keratin 7 immunoreactivity can be seen in the eosinophilic variant chromophobe renal cell carcinoma, the extent of staining is more than what is acceptable for renal oncocytoma (rare scattered cells). Hale colloidal iron staining is also useful in this setting, where it is positive in chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and negative in renal oncocytoma. However, technical challenges in performing the stain may hinder its use in general practice.

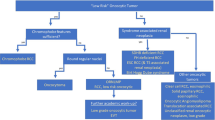

The low-grade oncocytic tumor is a recently described tumor that shares similar histologic features with renal oncocytoma as well. Microscopically, these tumors have a solid and compact nested growth pattern. Frequent areas of edematous stroma with loosely arranged eosinophilic cells are present, along with uniformly round to oval nuclei and focal perinuclear halos. However, contrasting with renal oncocytoma, these tumors are nonreactive to KIT and have a more diffuse reaction for keratin 7 [19]. Other differential diagnoses include succinate dehydrogenase–deficient renal cell carcinoma, unclassified renal cell carcinoma, eosinophilic solid and cystic renal cell carcinoma, acquired cystic disease-associated renal cell carcinoma, renal oncocytosis, and epithelioid angiomyolipoma. In difficult cases, immunohistochemical stains should help to establish the diagnosis.

In summary, adverse pathologic features are infrequently observed in renal oncocytoma, most commonly with tumors extending into the perinephric adipose tissue. In this large cohort of renal oncocytomas with adverse pathologic features, none of the patients had tumor recurrence, progression, or metastasis during a median follow-up of 60 months. The presence of adverse pathologic features in renal oncocytoma does not alter their benign course.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Zippel J. Zur Kenntnis der Onkocyten. Virchows Arch. 1941;308:360–82.

Klein MJ, Valensi QJ. Proximal tubular adenomas of kidney with so-called oncocytic features. A clinicopathologic study of 13 cases of a rarely reported neoplasm. Cancer. 1976;38:906–14.

Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM. The 2016 WHO classification of tumours of the urinary system and male genital organs-part A: renal, penile, and testicular tumours. Eur Urol. 2016;70:93–105.

MacLennan GT, Cheng L. Five decades of urologic pathology: the accelerating expansion of knowledge in renal cell neoplasia. Hum Pathol. 2019;95:24–45.

Omiyale AO, Carton J. Renal oncocytoma with vascular and perinephric fat invasion. Ther Adv Urol. 2019;11:1756287219884857.

Lieber MM, Tomera KM, Farrow GM. Renal oncocytoma. J Urol. 1981;125:481–5.

Harrison RH, Baird JM, Kowierschke SW. Renal oncocytoma: ten-year follow-up. Urology. 1981;17:596–9.

Amin MB, Crotty TB, Tickoo SK, Farrow GM. Renal oncocytoma: a reappraisal of morphologic features with clinicopathologic findings in 80 cases. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1–12.

Hes O, Michal M, Sima R, Vanecek T, Brunelli M, Martignoni G, et al. Renal oncocytoma with and without intravascular extension into the branches of renal vein have the same morphological, immunohistochemical, and genetic features. Virchows Arch. 2008;452:193–200.

Trpkov K, Yilmaz A, Uzer D, Dishongh KM, Quick CM, Bismar TA, et al. Renal oncocytoma revisited: a clinicopathological study of 109 cases with emphasis on problematic diagnostic features. Histopathology. 2010;57:893–906.

Wobker SE, Przybycin CG, Sircar K, Epstein JI. Renal oncocytoma with vascular invasion: a series of 22 cases. Hum Pathol. 2016;58:1–6.

Wobker SE, Williamson SR. Modern pathologic diagnosis of renal oncocytoma. J Kidney Cancer. 2017;4:1–12.

Williamson SR, Gadde R, Trpkov K, Hirsch MS, Srigley JR, Reuter VE, et al. Diagnostic criteria for oncocytic renal neoplasms: a survey of urologic pathologists. Hum Pathol. 2017;63:149–56.

Reuter VE, Argani P, Zhou M, Delahunt B. Members of the IIiDUPG. Best practices recommendations in the application of immunohistochemistry in the kidney tumors: report from the International Society of Urologic Pathology consensus conference. Am J Surg Pathol. 2014;38:e35–49.

Swalchick W, Shamekh R, Bui MM. Is DOG1 immunoreactivity specific to gastrointestinal stromal tumor? Cancer Control. 2015;22:498–504.

Zhao W, Tian B, Wu C, Peng Y, Wang H, Gu WL, et al. DOG1, cyclin D1, CK7, CD117 and vimentin are useful immunohistochemical markers in distinguishing chromophobe renal cell carcinoma from clear cell renal cell carcinoma and renal oncocytoma. Pathol Res Pr. 2015;211:303–7.

Hes O, Michal M, Kuroda N, Martignoni G, Brunelli M, Lu Y, et al. Vimentin reactivity in renal oncocytoma: immunohistochemical study of 234 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2007;131:1782–8.

Moch H, Ohashi R. Chromophobe renal cell carcinoma: current and controversial issues. Pathology. 2021;53:101–8.

Trpkov K, Williamson SR, Gao Y, Martinek P, Cheng L, Sangoi AR, et al. Low-grade oncocytic tumour of kidney (CD117-negative, cytokeratin 7-positive): a distinct entity? Histopathology. 2019;75:174–84.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Dr. KIA-O has examined the histologic slides and wrote the draft of the manuscript. Dr. LC has examined the histologic slides, supervised the progress of the work, and made the final input toward this manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval/consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Indiana University, Indianapolis, USA, under protocol number: 1301010350. Ethical approval for this study was waived.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Al-Obaidy, K.I., Cheng, L. Renal oncocytoma with adverse pathologic features: a clinical and pathologic study of 50 cases. Mod Pathol 34, 1947–1954 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00849-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41379-021-00849-z