Abstract

Psychological stress plays a critical role in the onset of depression by activating neuroimmune and endocrine responses, leading to dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and increased inflammation. This imbalance impacts key brain regions involved in mood regulation, such as the prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, and amygdala, contributing to the development of depressive symptoms. Moreover, stress induces immune dysregulation and inflammation in peripheral organs, including the gut, spleen, liver, lungs, and heart, which can result in metabolic disorders, cardiovascular disease, and immune dysfunction. Chronic stress also disrupts gut microbiota and alters the gut-brain axis via the vagus nerve, further exacerbating stress-related mental health issues. The cumulative effect of stress on peripheral organs significantly impacts both physical and mental health, linking systemic dysfunction to depression. This comprehensive review delves into the intricate mechanisms by which the immune system regulates mood and explores the etiological factors underlying dysregulated inflammatory responses in depression. We also summarize the connections between the brain and peripheral organs—bone marrow, spleen, gut, adipose tissue, heart, liver, lungs, and muscles—highlighting their coordinated regulation of immune function in response to psychological stress. Additionally, we investigate specific brain regions and neuronal populations that respond to stress stimuli, transmitting signals through autonomic and neuroendocrine pathways to modulate immune function. Finally, we discuss emerging therapeutic strategies that leverage the interaction between endocrine signaling and inflammatory responses for the effective treatment of depression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the 17th century, Descartes proposed the idea of interactionism, asserting that the mind and body are separate entities that interact and influence one another [1, 2]. Modern neuroscience now emphasizes the significant impact of mental states on physical health, shaping processes like metabolism, immune function, and the activity of various organs [3]. In turn, the physical state is sensed by the central nervous system (CNS) and adjusted through feedback mechanisms to maintain physiological balance [4]. These interactions are largely mediated by immune system cells, which play a key role in controlling inflammation and immune surveillance throughout the body. As research in neuroimmunology advances, the intricate connections between the psychological, nervous, and immune systems are becoming more apparent. While much research has focused on the central regulation of autonomic nervous functions, there is still limited understanding of the specific neurons involved in the brain-body circuits that regulate immune responses.

Psychological stress activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, rapidly increasing cortisol secretion. This short-term response mobilizes energy and temporarily suppresses non-essential functions, including certain immune responses. However, chronic stress desensitizes glucocorticoid receptors and impairs negative feedback, resulting in either persistently high or blunted cortisol levels [5, 6]. This dysregulation weakens cortisol’s anti-inflammatory effects and increases pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α.

At the cellular level, stress hormones such as cortisol and catecholamines directly alter immune cell function by modifying gene expression through transcriptional and epigenetic changes, shifting cells toward a pro-inflammatory state [7, 8]. Additionally, sympathetic activation mobilizes immune cells from lymphoid tissues into circulation, further promoting inflammation. Chronic stress also induces glucocorticoid resistance by downregulating receptor sensitivity, impairing the HPA axis’s negative feedback and sustaining a pro-inflammatory state that contributes to stress-related disorders like depression and anxiety [9].

In this review, we examine the literature on the interplay between psychological stress, depression, and the immune system. We overview the interactions between the CNS and peripheral organs across multiple axes—including brain-bone marrow, brain-spleen, brain-gut, brain-fat, brain-heart, brain-liver, brain-lung, and brain-muscle. We also explore how stress triggers immune responses in peripheral tissues, leading to physiological changes and behavioral symptoms of depression. By elucidating the bidirectional communication between the nervous and immune systems, we highlight its role in shaping stress responses and contributing to psychiatric and inflammatory disorders. Finally, we discuss innovative treatments for depression that target inflammation and hormone regulation.

The interplay between psychological stress and depression

Psychological stress-induced inflammatory response as a major risk factor for depression

According to recent estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study, around 300 million people worldwide are affected by depression [10]. Simultaneously, it is increasingly acknowledged that individuals with stress-related conditions, such as major depressive disorder (MDD), often display ongoing low-level systemic inflammation. These include elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the blood, disruptions in myelogenesis and lymphogenesis, and compromised physical barriers like the intestinal epithelium and the blood-brain barrier (BBB) [11,12,13,14,15]. Consequently, this inflammatory response can impair normal nervous system function. Remarkably, nearly a century ago, Nobel laureate Julius Wagner-Jauregg noted that immune activation, such as that induced by malaria vaccination, could potentially influence cognitive function [16].

Multiple meta-analyses have now firmly established that pro-inflammatory cytokines and acute phase proteins are elevated in patients with MDD [17,18,19,20]. There is a strong consensus that interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), and C-reactive protein (CRP) levels are significantly higher in the blood of MDD patients compared to healthy controls [21,22,23]. With advancements in cytokine measurement techniques, such as multiplexing [24], many other cytokines are currently being investigated in MDD patients [25, 26]. A more recent meta-analysis has reported elevated levels of IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, soluble IL-2 (sIL-2), C-C motif ligand 2 (CCL2), IL-13, IL-18, IL-12, IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1RA), and soluble TNF receptor 2 (sTNFR2) in MDD patients, while interferon-γ (IFN-γ) levels are reduced compared to healthy controls [20]. Moreover, an increase in the expression of genes linked to inflammatory pathways has been observed in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of patients with MDD. Aligning with protein-level findings, MDD patients show higher expression of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, macrophage migration inhibitory factor, and IFN-γ genes in PBMCs compared to controls, while IL-4 mRNA levels are reduced [27].

Abnormal blood cytokine levels have also been observed in other psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, suggesting a potential shared immune pathway underlying MDD, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder [28]. During the acute onset of these conditions, there is a marked increase in IL-6, TNF-α, IL-1RA, and sIL-2 receptor (sIL2R) levels, which then decline following treatment. This indicates that patients experiencing acute symptomatic psychosis may undergo an acute inflammatory response, aligning with previous findings of elevated inflammatory markers in healthy volunteers following stress. Additionally, psychological stress—a known risk factor for depression—can trigger an inflammatory response involving these pro-inflammatory cytokines and is linked to the onset of depressive symptoms [29]. Furthermore, approximately 40% of patients with hepatitis C or certain types of cancer who were treated with interferon-α developed depressive symptoms after starting treatment [30], highlighting the role of environmental factors in both depression and immune dysfunction. Furthermore, early-life trauma, such as abuse or violence, has a lasting impact on peripheral inflammation in adulthood [31,32,33,34] and is linked to a higher risk of developing depression [35]. Notably, the relationship between MDD and inflammation is more pronounced in individuals with a history of childhood adversity compared to those without [36], as reviewed [37, 38].

In summary, although psychological stress is commonly linked to outcomes such as increased cytokine production, it is essential to acknowledge that cytokine activity represents just one aspect of the broader picture. Gaining a more comprehensive understanding of the role of cytokines is crucial for further progress in this field.

Stress-induced alterations in the HPA axis

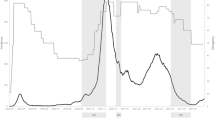

Stress is generally regarded as an essential evolutionary response to external stimuli, triggering “fight or flight” mechanisms that are crucial for survival [39] (Fig. 1). In mammals, this response is primarily mediated by the HPA axis, a negative feedback system that regulates the body’s physiological response to stress. Within seconds to minutes, HPA axis activation enables the body to prioritize critical functions like cognition and energy supply, while temporarily downregulating maintenance-related functions, such as digestion.

a Chronic psychological stress induces hyperactivation of the HPA axis, resulting in the release of glucocorticoids (GCs), which disrupt circuits responsible for regulating the stress response and maintaining physiological balance. CRH corticotropin-releasing hormone, ACTH adrenocorticotropic hormone, GCs glucocorticoids. b GCs are synthesized and released by the adrenal glands during HPA activation, can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) via P-glycoprotein (P-gp) transporters on endothelial cells, and bind to GC receptors on brain cells, including microglia and neurons. Prolonged binding of GCs to microglia receptors may induce a pro-inflammatory state in these resident immune cells of the central nervous system (CNS). P-gp: P-glycoprotein. c Prolonged and sustained stress also triggers the overactivation of various effector cells in the immune system, resulting in harmful effects. d Chronically elevated glucocorticoid levels promote the development of an inflammatory subset of enteric glia and cause transcriptional immaturity in enteric neurons, leading to gut dysmotility. The illustration was created using resources from Biorender.com.

Studies have reported conflicting findings regarding stress-induced changes in the HPA axis. Acute stress typically activates the axis, leading to a temporary increase in cortisol secretion that mobilizes energy and supports alertness. In contrast, chronic stress has been associated with a blunted cortisol response in some individuals, possibly due to glucocorticoid receptor desensitization or impaired negative feedback, which results in an overall downregulation of the axis over time [5, 6].

Upon activation of the HPA axis, neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) of the hypothalamus release corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF). CRF stimulates the anterior pituitary to secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn prompts the adrenal cortex to produce and release mineralocorticoids and glucocorticoids (corticosterone in rodents and cortisol in humans) into the bloodstream. Elevated cortisol then initiates a negative feedback loop by binding to glucocorticoid receptors (GRs) in the pituitary, hypothalamus, and hippocampus, thereby suppressing further CRF and ACTH release [6, 40].

Glucocorticoids bind to GRs not only within the HPA axis but also in various tissues, including the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, immune cells, neurons, and glial cells. As transcription factors, these hormones influence the structure and function of neural circuits that regulate stress-related behaviors [41]. In depression, a dysregulated HPA axis feedback loop leads to prolonged elevation of glucocorticoid levels, which is linked to symptoms such as hopelessness, sleep disturbances, and appetite changes. Moreover, long-term stress or chronic corticosterone exposure can result in neuronal atrophy in the hippocampus [42].

Prolonged stress also alters gene expression directly through glucocorticoid-driven transcription and indirectly via epigenetic modifications—such as DNA methylation, hydroxymethylation, and histone modification. These changes affect genes in brain regions critical for emotion and cognition, including the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex (PFC) [42]. Research shows that chronic stress and excessive glucocorticoids cause dendritic shrinkage and reduce synaptic plasticity in the hippocampus [43]. Consequently, these structural and functional changes disrupt the HPA axis, impair cognitive and emotional processes, and increase the risk of disorders, particularly depression [44]. In addition, chronic stress elevates allostatic load, placing strain on nearly every physiological system, including the immune system (Fig. 1).

Emerging research also indicates that individual differences—such as genetic predisposition, early-life stress, and comorbid conditions—can further modulate HPA axis reactivity, contributing to the variability observed across studies [45, 46]. Together, these findings underscore the complex interplay between acute and chronic stress responses and highlight the need for models that integrate both adaptive and maladaptive HPA axis alterations.

Depression and the immune system

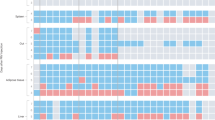

Activation of the innate and adaptive immune systems in peripheral tissues during stress and depression

The innate immune system acts as the body’s first line of defense against infections and stressors, operating in a preprogrammed manner [47]. Its key role in the pathophysiology of depression involves recruiting immune cells through cytokine production, activating the complement system, and initiating adaptive immune responses via antigen presentation [48]. Meanwhile, the adaptive immune system can form immunological memories of stressors, which may reduce the impact of future stress but could also contribute to the development of mood disorders [49].

Using repeated social defeat stress (RSDS) to investigate the effects of stress on white blood cell biology, researchers observed an increase in monocytes and granulocyte progenitor cells in the bone marrow, leading to blood mononucleosis and enhanced granulocyte production. They also identified stress-induced leukocyte transcription profiles that depend on β-adrenergic receptor signaling, which promotes the release of Ly6chigh monocytes and Ly6c intermediate granulocytes into circulation. This is accompanied by the upregulation of pro-inflammatory and myeloid commitment genes, alongside the downregulation of late-stage myeloid differentiation genes [50]. Similar results have been observed in humans with lower socioeconomic status, a persistent social stressor that triggers activation of the sympathetic nervous system. Individuals with low socioeconomic status exhibited elevated monocyte counts and leukocyte transcription signatures favoring mononucleosis and β-adrenergic signaling [50]. Similar results have been reported in rodent models using chronic variable stress (CVS), where monocytes and neutrophils increased in the blood and bone marrow of mice exposed to CVS for three weeks, an effect dependent on β3-adrenergic receptor signaling [51].

Stress also impacts the reactivity of innate immune cells. After exposure to RSDS, stressed mice showed an increased release of TNF-α and IL-6 from spleen macrophages when stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a bacterial endotoxin and toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) agonist. This heightened response was due to stress-induced glucocorticoid resistance [52]. These studies highlight the significant effects of stress on the innate immune system.

The role of the adaptive immune system in the pathogenesis of depression was first suggested when studies revealed elevated levels of circulating T helper cells (CD4+), cytotoxic T cells (CD8+), and B cells in MDD patients [53]. In these patients, impaired Th2 and Th17 cell maturation has been observed [34], along with a reduction in various pools of CD4+ T cells [54], and diminished B-regulatory cells [55]. Similarly, animal studies have shown that glucocorticoids and stress exposure modulate both T-cell and B-cell responses [56]. Mechanistically, growing evidence suggests that the adaptive immune system plays a crucial role in modulating the stress response.

Studies on lymphopenic mice, which lack a functional mature adaptive immune system, have demonstrated that transferring lymphocytes from stressed animals to stress-naïve mice can improve social behavior, decrease anxiety-like behaviors, and stimulate hippocampal cell growth [57]. Lymphocyte transplantation not only alleviated stress-induced effects but also led to the engraftment of these cells in the choroid plexus and meninges of the stressed recipient mice [58]. Additionally, CD8+ cytotoxic T cells respond to stress by modulating corticosterone levels, influencing behavior, and promoting the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, possibly by activating monocytes and macrophages [56]. Depending on the nature and intensity of the stress, elevated circulating immunomodulators may indirectly trigger neuroinflammation through cytokine release from capillary endothelial cells near the BBB [59] and vagus nerve activation in response to peripheral inflammatory signals [60].

The central-peripheral neuroimmune system in the inflammatory regulation of stress and depression

The brain is no longer considered an entirely immunologically privileged area

Before a full understanding of the complex interactions among the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems, researchers believed that the brain was an immune-privileged site—an environment where no immune cells or factors could enter and influence brain function under normal conditions. They also assumed that immune regulation depended solely on the hematopoietic system. However, subsequent research revealed the BBB, a structure composed of tightly connected endothelial cells that selectively blocks immune cells, blood components, and pathogens from entering the brain. Under normal conditions, peripheral immune cells remain excluded from the brain parenchyma, though they can be found in the CSF and meninges [61].

When the BBB is compromised, macrophages and T cells can infiltrate the brain, potentially causing damage to the parenchyma [61]. Certain regions, such as the periventricular organs and choroid plexus, permit immune cell entry due to inherent BBB disruptions. The choroid plexus, which produces CSF, also facilitates lymphocyte entry for immune surveillance [62]; indeed, under typical conditions, a higher proportion of CD4+ T cells is present in the CSF [62]. T cells enter the brain via extravasation—a process aided by increased expression of adhesion molecules and integrins. Specifically, T cells express very late antigen-4 (VLA-4) and lymphocyte function-associated antigen-1 (LFA-1), which interact with vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) on endothelial cells, thereby enabling their infiltration.

Additionally, chemokines such as CCL9 and CCL20 produced by the choroid plexus attract T cells to the brain, as demonstrated in studies on autoimmune diseases [63, 64]. The recent discovery of the brain’s lymphatic system has also identified another pathway for immune cells to access the meninges [65]. This system drains immune cells and soluble factors from the CNS to the cervical lymph nodes [66] and helps maintain CNS-reactive T cells in the meningeal space, promoting immune tolerance. However, during infections, this system may trigger aberrant T cell activation and subsequent CNS damage.

Beyond immune cells, neurons and glial cells produce significant amounts of cytokines following CNS infections or trauma. Many cytokines and their receptors are expressed in the brain [67, 68], and both peripheral and CNS-derived cytokines regulate various brain functions. For example, IL-1 influences thermogenesis, sleep, appetite suppression, and the release of pituitary hormones such as corticotropin—either directly or via corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus. Similarly, IL-6 has comparable effects and can hinder long-term potentiation [69]. IL-2 exhibits analgesic properties, with studies showing different interactions between IL-2 receptors on immune cells and neurons [70]. It remains unclear whether cytokine receptors in the nervous, endocrine, and immune systems are identical, much like BBB-associated cytokine transporters.

In this part, the conceptual framework unifies multiple brain-peripheral axes by highlighting common neuroimmune and endocrine communication pathways that regulate bodily functions. This integrative approach clarifies how diverse peripheral regions work together to maintain homeostasis and how their dysregulation can contribute to psychiatric disorders.

Brain-bone marrow axis

Previous studies have shown that immune organs, including the bone marrow, which contains hematopoietic stem cells that give rise to various blood cells like monocytes, neutrophils, and lymphocytes, are innervated by the autonomic nervous system. These findings provide a solid foundation for further exploration of the bidirectional communication between the brain and body within this framework [71]. Using a retrograde virus tracing technique, one study identified specific brain areas that regulate bone marrow activity [72]. They identified several regions, such as the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), gigantocellular reticular nucleus (Gi), lateral paragigantocellular nucleus (LPGi), raphe pallidus nucleus (RPa), and ventral tegmental area (VTA), that affect the lumbar sympathetic ganglion and the mediolateral cell column in the thoracic spinal cord. Additionally, the ventrolateral medulla, periaqueductal gray (PAG), locus coeruleus (LC), lateral nucleus of the hypothalamus (LH), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus (ARH), amygdala, hippocampus, insular cortex, septum, and motor cortex also play a role in regulating bone marrow function [72].

Several brain regions that innervate the bone marrow are notably involved in the stress response, reward processing, and the development of depression and anxiety. In both MDD patients and rodent models of chronic stress, dysregulation of dopaminergic pathways from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens (NAc), prefrontal cortex (PFC), amygdala, and hippocampus has been observed [73, 74]. Similarly, in rodent models of chronic stress, regions within the hypothalamus, such as the paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PVH), lateral hypothalamus (LH), and arcuate nucleus (ARH), show increased activation [75,76,77]. As a central part of the HPA axis, the PVH regulates stress responses through neuroendocrine signaling. Other stress-sensitive areas that project to the bone marrow, such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST) and the central amygdala (CeA), integrate emotional stimuli and activate the HPA axis, promoting anxiety and fear behaviors [5, 78]. However, the direct impact of these brain regions on immune function in the bone marrow remains an open question. Both MDD patients and rodents exposed to chronic stress have been linked to conditions such as mononucleosis, neutrophilia, and lymphocytopenia, which may result from alterations in hematopoietic stem cell populations or the mobilization of white blood cells from the bone marrow [79, 80]. Specifically, chronic variable stress or chronic social defeat stress (CSDS) causes an expansion of bone marrow progenitor cells while reducing lymphoprogenitor cells [79, 80]. The bone marrow is known to receive significant sympathetic innervation, facilitating the release of white blood cells into circulation under both stressful and normal conditions.

Norepinephrine signaling, released by sympathetic nerve fibers in the bone marrow niche, has been shown to reduce the expression of CXCL12, a chemokine that typically inhibits hematopoiesis and retains neutrophils and monocytes within the bone marrow [81, 82]. Research further suggests that RSDS decreases CXCL12 expression, facilitating the release of monocytes. This effect can be reversed by adrenalectomy or the use of corticosterone synthesis inhibitors. Since neurons in the PVH and LC project to sympathetic centers in the brainstem and spinal cord, increased sympathetic activity from the activation of these regions may influence hematopoietic stem cell and leukocyte dynamics in the bone marrow under chronic stress conditions [83, 84]. To explore the central regulation of stress-induced white blood cell mobilization, a recent study employed chemical genetics to modulate neuronal activity in specific brain regions and then measured circulating immune cell levels. The findings revealed that activating CRH+ neurons in the PVH raised plasma corticosterone levels, leading to the retention of T cells, B cells, and monocytes within the bone marrow and reducing their circulation. Additionally, optogenetic stimulation of the motor cortex or medulla induced CXCL1 expression in skeletal muscle, while inhibition or ablation of these areas attenuated stress-induced neutrophil mobilization [85]. Moreover, chemical activation of dopaminergic neurons in the VTA, associated with reward processing, increased circulating B cells, partially through sympathetic nervous system involvement [86].

These findings suggest that brain activity can regulate the production, retention, and release of white blood cells from the bone marrow in response to stress through the HPA axis, involving the autonomic nervous system and peripheral chemokines (Fig. 2). However, further research is needed to identify the upstream neural circuits involved in these processes and to better understand how the CNS regulates myelogenesis and mononucleosis.

The motor cortex facilitates the recruitment of neutrophils from skeletal muscle, accelerating their chemokine CXCL1-mediated migration from the bone marrow to peripheral tissues. In contrast, the paraventricular hypothalamus regulates the migration of lymphocytes and monocytes from the bloodstream to the bone marrow through glucocorticoid signaling in leukocytes, thereby modulating adaptive immune responses to viral infections and autoantigens. The illustration was created using resources from Biorender.com.

Brain-spleen axis

The spleen, a crucial organ where immune cells encounter pathogens and antigens to initiate both innate and adaptive immune responses, is a significant target for nervous system-driven immune regulation [87]. Recent research has identified a critical anatomical pathway that enables direct neural modulation of the adaptive immune response in the spleen [88]. A notable connection within the brain-spleen axis was observed in a mouse model of mild stress, where CRH neurons associated with CeA and PVN directly interact with the splenic nerve to regulate antibody production [88] The researchers used adeno-associated virus (AAV) injection, retrograde virus tracing, and optogenetics to confirm the existence of a neural pathway originating from CRH neurons in the amygdala and PVN that extends to the spleen. In addition to mapping these anatomical connections, they explored neuroimmune activity linking the brain and spleen. Using CRH neuron deletion, as well as DREADD-based chemogenetic inhibition and activation, they demonstrated that CRH neuronal activity in the CeA and PVN controls plasma cell production during the B cell response in the spleen [88]. In a mouse stress model involving elevated-platform standing, concurrent activation of CRH neurons was found to promote plasma cell formation through the PVN/CeA-splenic nerve axis [88]. This indicates that the brain-spleen axis may boost host adaptive immunity by increasing antibody production in response to physical and psychological stressors. Importantly, this study reveals a novel brain-spleen neural axis where CRH neurons directly modulate immune function in the spleen through neural circuits. This mechanism works alongside the well-established pituitary-adrenal neuroendocrine pathway, which has an immunosuppressive effect.

The recognition of the brain-spleen axis has provided substantial evidence linking neuroinflammation, regulated by this axis, to depression [89]. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) plays a crucial role in depression [90,91,92,93,94]. A postmortem study showed alterations in the expression of BDNF and its precursor, proBDNF, in both the brain and spleen of patients with MDD [95]. Another study revealed a positive correlation between colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R) protein levels in the spleen and parietal cortex of MDD patients [96]. Furthermore, the elimination of microglia using the CSF1 inhibitor PLX5622 led to a concurrent reduction in Iba1 protein levels in both the spleen and brain of mice, highlighting the involvement of the brain-spleen axis [97]. Pretreatment with PLX5622 also inhibited monocyte transport from the spleen to the brain, reducing stress-induced anxiety and neuroinflammation [98]. Additionally, in a RSDS model of depression, targeting IL-1R1/IL-1β signaling was found to alleviate neuroinflammation and prevent the development of anxiety or depression-like behaviors [99].

A single dose of LPS has been shown to induce splenomegaly and depression-like behaviors through systemic inflammation via the vagus nerve [100]. Additionally, denervation of the splenic nerve blocked depression-like behaviors in LPS-treated mice [101] and in Chrna7 knockout mice [102]. LPS-induced splenomegaly and depression-like behaviors were alleviated after a single administration of the novel antidepressant arketamine [103,104,105,106]. One study highlighted the role of the splenic heme biosynthesis pathway in the long-lasting prophylactic effects of arketamine in LPS-treated mice [107]. A recent study revealed that oxidative phosphorylation plays a role in the antidepressant effects of arketamine, acting through the brain-spleen axis in a vagus nerve-dependent manner [108]. Together, these findings suggest that abnormalities in the brain-spleen axis may contribute to depression, and that arketamine’s antidepressant effects could be mediated through this axis [109].

In addition to the discoveries mentioned earlier, other components of the brain-spleen axis have also been linked to depression. For instance, daily administration of the endocannabinoid receptor agonist WIN55,212–2 before RSDS for six days resulted in spleen enlargement and a reduction in anxiety-like behaviors in mice, alongside lower levels of circulating monocytes and neuroinflammatory markers (IL-1β and Iba1) in the brain [110]. Moreover, in a LPS-induced depression model, activation of the α7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) pathway via the agonist PNU282987 reduced microglial activation and neuroinflammation. Notably, in response to social disruption stress, Lactobacillus RNA translocated from the gut lumen to splenic monocytes, which correlated with increased IL-1β and IL-23 mRNA levels, suggesting a potential innate immune interaction between the microbiota and the spleen that may impact the brain-spleen axis [111]. Additionally, the anti-inflammatory drug diminazene aceturate was shown to attenuate systemic inflammation in male mice by modulating the gut microbiota-serotonin brain-spleen sympathetic axis, which operates through a complex neuroimmune circuit. This circuit involves signaling from gut microbes, elevated central serotonin levels, and subsequent activation of the splenic sympathetic neural network [112].

These findings expand the understanding of the brain-spleen axis by incorporating its interactions with other organs and tissues, such as the gut microbiome. The complex communication between the brain, spleen, and gut underscores the importance of these interconnected systems and their potential roles in both health and disease.

Brain-gut axis

The gut microbiota plays a key role in regulating the immune system by maintaining immune homeostasis and modulating responses to pathogens. It interacts with immune cells to support the development of both innate and adaptive immunity. In the context of depression, the gut microbiota influences the brain-gut axis by modulating neuroinflammation and affecting neurotransmitter production, such as serotonin. Dysbiosis, or an imbalance in gut microbial communities, has been linked to increased inflammation and altered stress responses, which contribute to the development and progression of depression. These insights suggest that targeting the gut microbiota could offer new therapeutic approaches for treating depression [113,114,115,116,117]. The GI tract, constantly exposed to pathogens and dietary antigens and rich in lymphoid follicles, is an immune-related tissue particularly sensitive to stress. A significant body of research has investigated the interplay between the central and enteric nervous systems and its influence on both local and systemic inflammation (Fig. 3).

The gut microbiota interacts with the brain through various mechanisms, including activation of the vagus nerve, production of microbial metabolites like short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), and endocrine signaling via intestinal epithelial cells (such as I-cells releasing CCK and L-cells releasing GLP-1, PYY, and other peptides). These communication channels enable the microbiota-gut-brain axis to regulate key central physiological processes, including neurotransmission, neurogenesis, neuroinflammation, and neuroendocrine signaling, all of which are closely linked to stress responses. Disruptions in gut microbiota balance can alter these processes and may contribute to the development of stress-related disorders. The illustration was created using resources from Biorender.com.

Certain microbiota strains, such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium species, modulate brain inflammation by balancing pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines after stress [118]. Additionally, gut microbiota can influence neurogenesis by regulating neuromodulator production, such as serotonin, thereby promoting new neuron growth and enhancing brain plasticity following stress exposure [119]. A recent study demonstrated that targeted ablation of the serotonin reuptake transporter in the intestinal epithelium produced anxiolytic and antidepressive-like effects without harming the GI tract or brain; conversely, inhibiting epithelial serotonin synthesis increased anxiety and depression-like behaviors [120]. Moreover, a clinical study found significant differences in gut microbiota composition between responders and non-responders to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), with specific taxa such as Ruminococcus, Bifidobacterium, and Faecalibacterium being more abundant in responders [121]. Functional analysis revealed that acetate degradation and neurotransmitter synthesis pathways were upregulated in the responder group, suggesting that gut microbiota influences the antidepressant effects of SSRIs through these metabolic pathways [121].

Retrograde PRV tracing is frequently employed to identify specific brain regions that control different segments of the gut, with the brainstem playing a pivotal role in this regulation. For example, regions such as the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS), LC, dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV), periaqueductal gray (PAG), raphe pallidus (RPa), gigantocellular nucleus (Gi), and parabrachial nucleus (PB) primarily govern the rectal region [122]. In contrast, the NTS, DMV, RPa, and Gi regulate the ileum. The duodenum, however, is influenced by a broader network that includes the NTS, LC, DMV, RPa, PB, Gi, lateral hypothalamus (LH), paraventricular hypothalamus (PVH), bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (BNST), central nucleus of the amygdala (CeA), insular cortex, and motor cortex [123].

These brain regions work together through complex neural circuits, communicating with the gut via neural (e.g., the vagus nerve), endocrine, and immune pathways. Disruptions in the gut microbiota can affect neurotransmitter systems (such as serotonin and GABA), neuroinflammatory processes, and stress hormone secretion, which in turn may alter the functioning of these brain regions. A detailed understanding of the localization and connectivity of these regions provides valuable insights into how gut-derived signals (e.g., short-chain fatty acids, tryptophan metabolites, or bile acids) influence brain function and behavior. This framework not only clarifies the neurobiological basis of stress-related psychiatric disorders but also suggests that targeted interventions—such as probiotics or neuromodulatory treatments—might help restore balance in these interconnected systems [124,125,126].

Microbiome depletion using an antibiotic cocktail has been linked to increased resilience in mice following CSDS [127]. Additionally, the presence of Bifidobacterium in the gut microbiota has been shown to confer resilience to CSDS in mice [128]. An abnormal composition of gut microbiota is also associated with resilience or susceptibility to inescapable electric stress [129, 130]. It has been reported that the brain-gut axis may contribute to the antidepressant effects of arketamine in the CSDS model [131, 132]. Moreover, fecal microbiota transplantation from rodents displaying depression-like behaviors induced similar behaviors in recipient mice in a vagus nerve-dependent manner [133,134,135]. Collectively, these findings suggest that neuroinflammation mediated by the vagus nerve-dependent gut-brain axis plays a role in the development of depression [136].

Growing evidence suggests that chronic stress negatively affects GI function, leading to gut dysmotility, dysbiosis, and low-grade inflammation [137, 138]. Stress has also been shown to exacerbate symptoms of experimental colitis in rodents, with indications that this response is centrally regulated by the brain. For instance, one study reported that chronic water avoidance and restraint stress heightened colon damage and increased myeloperoxidase activity in rodents with 2,4,6-trinitrobenzenesulphonic acid (TNB)-induced colitis[139]. Furthermore, intraventricular injections of CRH, produced by cells in the PVH and CeA, aggravated both TNB- and stress-induced colitis, whereas CRH antagonists helped alleviate these effects [139]. Additionally, intraperitoneal administration of orexin, primarily produced by cells in the LH, has been shown to mitigate alcohol-induced gastric mucosal injury.

Mechanistically, a recent study demonstrated that chronic restraint stress worsens dextran sodium sulfate-induced colitis via an HPA axis-dependent pathway. The researchers observed that neuroglial cells respond to stress by upregulating CSF1, which, in turn, drives colitis through the induction of TNF production in colon monocytes [140]. Although these studies indicate that the CNS regulates GI inflammation and homeostasis, they have not yet identified the specific neural cell populations responsible for these effects.

Brain-adipose axis

The bidirectional communication between adipose tissue and the nervous system is governed by neural and hormonal signals, as well as intracellular networks within the tissue. White and brown adipose tissue are innervated by pathways involving the hypothalamus, brainstem, spinal cord, and sympathetic ganglia [141, 142]. Fat cells secrete proteins, such as leptin and adiponectin, which influence the nervous system and peripheral tissues, regulating fat storage and insulin sensitivity [143,144,145]. Using the tracer True Blue, researchers mapped neural projections from white and brown adipose tissue to the dorsal root ganglia, where sensory neuron cell bodies reside, as well as central sensory circuits from groin [146] and epididymal white adipose tissue to the brain[147]. This evidence highlights a complex interaction between the afferent and efferent nerves of the nervous system and adipose tissue.

Leptin, an adipokine linked to depression in humans, exhibits antidepressant and anti-anxiety effects in rodent models. Recent research suggests that leptin’s antidepressant effects are mediated by LepRb signaling in limbic and prefrontal brain regions, while its anxiolytic effects involve leptin’s action on dopamine neurons in the ventral midbrain, which project to the central nucleus of the amygdala [148]. Another study found that brown fat cells are a primary source of IL-6 during psychological stress. Specifically, gene deletion of the β3 adrenergic receptor in brown fat cells lowers stress-induced IL-6 levels, indicating that sympathetic nerve regulation of IL-6 release from brown fat occurs via β3 adrenergic signaling during acute stress. Additionally, the study showed that sympathetic activation prompts IL-6 secretion from adipocytes, contributing to hyperglycemia through gluconeogenesis in response to psychological stress [149]. Moreover, further research highlights the pivotal role of the adipose PPARγ-adiponectin axis in stress susceptibility and negative emotion-related behaviors, suggesting that targeting PPARγ in adipose tissue could offer new therapeutic strategies for depression and anxiety [150].

The bidirectional interaction between adipose tissue and the nervous system is mediated through neural, hormonal, and intracellular networks. Adipose tissues produce key proteins like leptin and adiponectin, which regulate fat storage, insulin sensitivity, and influence the nervous system, while neural projections from fat tissues connect to sensory pathways. Leptin has shown antidepressant and anti-anxiety effects, with its signaling in specific brain regions contributing to mood regulation, and brown fat cells have been identified as sources of IL-6 during psychological stress, highlighting the role of the adipose tissue-brain axis in stress responses. Recent studies also suggest that targeting the adipose PPARγ-adiponectin axis could offer new strategies for treating depression and anxiety, though further research is needed to fully understand these mechanisms.

Brain-heart axis

The CNS regulates cardiovascular function by modulating both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems (Fig. 4). The brain-heart axis plays a crucial role in modulating immune responses through neurocardiac pathways, which affect the autonomic nervous system and inflammatory processes [151,152,153]. Brain signals, particularly via the vagus nerve, help regulate heart function and systemic inflammation by controlling cytokine release and immune cell activity. Disruptions in this axis can lead to altered heart function and immune dysregulation, contributing to cardiovascular diseases and chronic inflammation. The CNS and cardiovascular systems are in constant coordination and sometimes opposition [154, 155]. The neurons responsible for generating and controlling cardiovascular activity are located in what is known as the cardiovascular center [156]. This center spans from the spinal cord to the cerebral cortex, involving areas such as the anterior cingulate cortex, insula, limbic lobe, hypothalamus, and brainstem, particularly the medulla oblongata [156]. The medulla acts as a crucial cardiovascular control center, containing the vasoconstrictor and vasodilator regions, neurons of the nucleus tractus solitarius, and the cardioinhibitory area [157]. Despite lacking direct anatomical connections, this center regulates cardiac function with precision through neural pathways.

Cardiovascular function is regulated by both the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. The heart’s β1-adrenoreceptors receive cortisol from the adrenal cortex and norepinephrine from synaptic connections. Cardiovascular activity is also influenced by immune cells from the spleen and bone marrow, renin, angiotensin, and aldosterone from the kidneys, and catecholamines from the adrenal medulla. Additionally, acetylcholine signaling from the peripheral nervous system plays a crucial role in regulating cardiac function. The illustration was created using resources from Biorender.com.

Research into the brain-heart axis has made significant progress. By focusing on Piezo1 channels in the thoracic dorsal root ganglion, where the cell bodies of cardiac sensory neurons are located, researchers have uncovered a novel neuroimmune mechanism involving Piezo1/IL-6, which facilitates post-infarction ventricular remodeling [158]. Another study revealed that heart-mediated pressure beats significantly influence olfactory bulb neuron activity, a process dependent on local pressure beats and mediated by the mechanosensitive Piezo2 channel [159]. This suggests that the heart can directly modulate neural activity through cardiac rhythm, potentially affecting cognitive, emotional, and autonomic states, and providing a rapid bidirectional communication pathway between the body and brain. Further research identified that glutaminergic neurons in the primary motor cortex (M1) influence cardiac function, with the downstream raphe nucleus (MnR) serving as a key relay brain region within the M1 circuit affecting the heart. A myocardial infarction (MI) model confirmed that M1 neuron activity impacts cardiac function under pathological conditions [160].

Liao et al. [161] explored the potential of sotagliflozin, a sodium-glucose cotransporter 1/2 inhibitor, to treat depression following MI by targeting the gut-heart-brain axis. Sotagliflozin improved both cardiac function and depression-like behaviors in an MI animal model, with changes in gut microbiota, particularly in the Prevotellaceae family. Fecal microbiota transplantation confirmed that gut microbiota played a role in these beneficial effects, suggesting the drug’s potential for treating MI-related depression via microbial mechanisms.

These findings enhance our understanding of the neural connectivity between the brain and heart, shedding light on how specific brain regions synchronize with cardiac activity during stress.

Brain-liver axis

The liver is the largest organ and gland in the body, containing numerous enzymes influenced by environmental factors that are essential for metabolism and detoxification. It also synthesizes key biochemical factors required for optimal brain function. The brain-liver axis plays a crucial role in maintaining metabolic homeostasis by regulating processes such as glucose and lipid metabolism through neural and hormonal signals [162, 163]. Disruptions in this axis can lead to liver-related diseases like non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, as well as metabolic disorders such as insulin resistance and obesity. In patients with liver diseases, elevated inflammatory biomarkers—such as IL-6, TNF-α, and CRP—are commonly observed and have been linked to the severity of depression [164, 165]. This suggests that systemic inflammation from liver dysfunction may trigger neurobiological changes that worsen depressive symptoms, making these markers potential indicators of depression severity and treatment response. Overall, chronic liver conditions can affect brain function by causing neuroinflammation and cognitive impairments, highlighting the bidirectional impact of the brain-liver axis on health and disease.

When BBB permeability is altered by pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β, toxins like ammonia and allobiotin can enter the brain more freely, triggering a pro-inflammatory response [166]. Research in mice has shown that acute liver failure disrupts the BBB, allowing TNF-α and IL-1β to cross into the brain, worsening cerebral function. Additionally, the vagus nerve’s afferent fibers sense sensory input from the liver and relay it to the solitary nucleus in the CNS, which regulates parasympathetic activity in the liver [167]. Brain signals, particularly via the vagus nerve, are crucial for regulating VLDL triglyceride secretion and reducing hepatic lipid content. Exogenous stimulation of the vagal reflex pathway connects hepatic sensory input with brainstem activity, efferent vagus nerve signaling, and intestinal neurons [168].

Yang et al. found that mice with hepatic ischemia/reperfusion (HI/R) injury showed splenomegaly, systemic inflammation, depression-like behaviors, decreased synaptic protein expression in the PFC, and disrupted gut microbiota composition [169]. These effects were prevented by subdiaphragmatic vagotomy [169]. Similarly, mice with common bile duct ligation (CBDL) showed splenomegaly, elevated plasma IL-6 and TNF-α levels, depression-like behaviors, reduced PFC synaptic protein expression, and gut microbiota alterations [170], with subdiaphragmatic vagotomy also blocking these effects. Interestingly, a single dose of arketamine improved depression-like phenotypes in both HI/R and CBDL models [169, 170], highlighting the role of the gut-liver-brain axis via the subdiaphragmatic vagus nerve. Additionally, a recent study found that dietary intake of sulforaphane glucosinolate prevented splenomegaly, systemic inflammation, depression-like behaviors, and reduced synaptic protein expression in the PFC through the gut-liver-brain axis [171]. Collectively, these findings suggest that depressive symptoms in patients with liver injury may be mediated by this axis.

Soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH) plays a key role in the metabolism of polyunsaturated fatty acids by converting bioactive epoxides, such as epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) derived from arachidonic acid, into less active diols. This enzymatic process diminishes the beneficial effects of these epoxides, which include anti-inflammatory, vasodilatory, and cardioprotective properties. Inhibiting sEH can help preserve the bioactivity of epoxides, making it a potential therapeutic target for inflammatory diseases, including depression [172,173,174,175,176,177,178,179]. Research has shown that sEH activity in hepatocytes regulates plasma levels of 14,15-EET, which enhances synaptic function by acting on astrocytes in the medial PFC, contributing to antidepressant-like effects observed with liver Ephx2 deficiency [180]. This research suggests that liver-controlled metabolic pathways are involved in depression-like behavior and highlights sEH in liver cells as a potential gene therapy target to down-regulate liver Ephx2 expression and induce antidepressant effects [180]. Furthermore, a study using postmortem samples found elevated expression of sEH proteins in the brain and liver of MDD patients, indicating a potential role of the brain-liver axis in depression [181].

Researchers have discovered that chronic aerobic exercise strengthens cortical neural networks by promoting amino acid metabolism in the liver. This process involves the secretion of specific methylation donors, such as S-adenosylmethionine, into the brain, which facilitates RNA methylation (m6A) of excitatory synapse-associated transcripts in the medial PFC (mPFC). This mechanism enhances resistance to chronic environmental stress and prevents anxiety-like behavior in mice. These findings reveal a novel liver-brain axis, highlighting how liver-derived metabolites regulate RNA methylation in the brain and influence anxiety circuits [182]. Recently, a “vagal-liver-cortical” loop was identified, where the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus activates hepatic lipocain 2 (LCN2) production through the efferent vagus nerve during stress [183]. This production, in turn, suppresses neuronal activity in the mPFC, leading to anxiety-like behavior. This discovery sheds light on how stress-induced increases in hepatic LCN2 disrupt cortical function, providing a molecular basis for early diagnosis or intervention of anxiety.

Collectively, the brain-liver axis plays a crucial role in maintaining metabolic homeostasis and regulating cognitive and emotional functions, with disruptions contributing to mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety. Recent research underscores the impact of liver-derived metabolites and vagus nerve signaling on brain function, especially in response to stress. Gaining insight into these mechanisms could provide new therapeutic targets for treating liver-related psychiatric and neurological disorders.

Brain-lung axis

The lungs, constantly exposed to the external environment, host a unique microbial community. Interactions between these microorganisms and the environment can trigger physiological changes in both the GI tract and the pulmonary system [116, 184]. One study showed that depleting the microbiome with antibiotics protected against LPS-induced acute lung injury, highlighting the importance of the gut-microbiota-lung axis [185]. Another study found that intratracheal LPS injection in mice caused severe lung injury and demyelination in the corpus callosum, while cervical vagotomy reduced LPS-induced plasma IL-6 levels and demyelination in the corpus callosum without affecting lung injury [186]. These findings suggest that acute lung injury can lead to brain demyelination via a cervical vagus nerve-dependent lung-brain axis. Current research on the lung-brain axis focuses on mechanisms such as the direct migration of microorganisms and their metabolites, immune communication, vagus nerve signaling, and regulation by the HPA axis (Fig. 5).

The brain communicates with the lungs by releasing neurotransmitters that regulate lung function through the vagus nerve and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. The connection between the lungs and the brain is further established via microbiota, metabolic, and immune pathways that can potentially cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) to influence the central nervous system (CNS) and modulate immune cells in the brain, thereby affecting cerebral function. The illustration was created using resources from Biorender.com.

The brain-lung axis operates through a bidirectional neuroanatomical communication pathway via the autonomic nervous system, specifically the parasympathetic (vagus) nerves and the partially sympathetic upper thoracic spinal cord [187]. The brain releases neurotransmitters that influence lung function, sending physiological signals while receiving feedback from the lungs [187]. Numerous studies have highlighted the involvement of sympathetic and vagus nerves in lung injury following brain injury. Pulmonary mechanoreceptors allow the lungs to detect mechanical and chemical stimuli, which are relayed to the brain through the autonomic nervous system [188]. The pulmonary parasympathetic inflammatory reflex includes vagal sensors in the lungs, α7-nAChR-expressing cells, and a brain integration center. Vagal nerve endings in the airway or alveolar epithelium detect various stimuli and transmit signals to brain centers via afferent vagus nerves [189]. This vagal activation occurs in conditions such as endotoxemia [190], acute respiratory failure [191], ischemia-reperfusion injury, and asthma, facilitating lung-brain communication.

Researchers who initially discovered the lung-brain axis found a strong correlation between lung microbiota and the immune reactivity of the brain, emphasizing that dysregulation of lung microbiota significantly affects susceptibility to autoimmune diseases in the CNS [192]. Through local neomycin treatment, bacteria selectively migrated towards LPS-rich clusters, activating type I interferon in brain microglia, which suppressed pro-inflammatory responses and improved autoimmune symptoms. This data reveals the underlying mechanisms of the lung-brain axis and highlights the influence of peripheral organs on CNS immune responses [192].

Additionally, another study showed that mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) delivered peripherally could activate vagus sensory neurons in the lungs that project to the nucleus solitarius, leading to serotonin release from the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN) [193]. This activation, mediated through the BDNF-TrkB signaling pathway, was also achieved through inhalation of TrkB agonists, alleviating depressive and anxiety-like behaviors in mice with chronic rhinosinusitis. The study highlights the regulatory role of peripheral MSCs in CNS function and proposes the “pulmonary vago-brain axis” as a potential therapeutic strategy for MDD. The identification of this pathway offers a compelling case for exploring inhalation therapy targeting the vagus-dependent lung-brain axis in depression treatment. Recent research has also shown that during lung infection, direct communication occurs between the lungs and brain, utilizing the same sensory proteins and neurons involved in pain pathways to relay infection signals to the brain, triggering sensations like fatigue and loss of appetite. Lung TRPV1+ nociceptors detect LPS in non-biofilm bacterial pneumonia through TLR4 activation, initiating an acute stress neural circuit [194].

Collectively, the brain-lung axis highlights the bidirectional communication between the lungs and brain, where lung microbiota and vagus nerve signaling influence immune responses and brain function. Research has shown that disruptions in lung microbiota can impact susceptibility to CNS autoimmune diseases, while activation of pulmonary vagus neurons by MSCs can alleviate depressive and anxiety-like behaviors. This axis offers new insights into therapeutic strategies for conditions like depression and autoimmune disorders.

Brain-muscle axis

Skeletal muscle, as one of the largest organs in the human body, plays a crucial role in the motor system by providing postural support, facilitating voluntary movement through strength and momentum, and contributing to involuntary actions like breathing and reflexes [195]. Muscle-to-brain communication occurs through various pathways, including the secretion of growth factors and cytokines by muscles [196, 197]. Although many circulating factors cannot cross the BBB, they can still affect the brain by binding to receptors on BBB endothelial cells, such as growth differentiation factor 11 (GDF11) [198, 199]. Some circulating factors, including myokines like irisin, cathepsin B, BDNF, IL-6, and FGF-21, can cross the BBB and directly signal brain cells [197, 200, 201]. Besides myokines, muscle-released metabolites (myometabolites) and other signaling molecules, such as bioactive lipids, enzymes, and exosomes, also contribute to communication with the CNS (Fig. 6). In addition to endocrine signaling via the bloodstream, direct neuromuscular pathways may transmit signals from skeletal muscle to the brain. For example, fluorescent tracers injected into skeletal muscle have been shown to reach the spinal cord through retrograde axonal transport of motor neurons [202], suggesting that actin may utilize a similar route [203].

The brain regulates muscle function and peripheral metabolism through the control of sympathetic nerve activity and cortisol secretion, mediated by internal signaling and the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. During muscle contraction, skeletal muscles release significant amounts of myokines, metabolites, exosomes, and actin molecules into the bloodstream. These bioactive substances, either as soluble factors or enclosed within extracellular vesicles (EVs), can cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and promote neurotrophic signaling in brain regions involved in cognitive, executive, and metabolic regulatory functions. The illustration was created using resources from Biorender.com.

As research advances, new pathways for muscle-to-brain communication are being uncovered. Studies have demonstrated that disruptions in muscle protein homeostasis related to aging [204] can initiate long-distance signaling processes that help slow age-related deterioration in brain and retinal function [205]. Skeletal muscle secretes the enzyme Amyrel, which leads to brain maltose production, reducing the accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins in the aging brain [205]. These findings highlight Amyrel as a newly identified myokine and reveal a distinct muscle-to-brain mechanism active during physiological stress.

Research also indicates that signals from skeletal muscle can impact mood and emotional behavior. Kynuridine, a tryptophan metabolite, is able to cross the BBB and influence stress-induced depression-like behavior [206]. Kynurenine, derived from tryptophan, is converted into kynurenic acid by kynurenine aminotransferase in tissues such as the liver, immune cells, and muscle [207]. This conversion is enhanced during physical exercise in skeletal muscle via a pathway involving PGC-1α, PPARα, and PPARδ [208, 209]. Additionally, skeletal muscle releases the bioactive molecule BDNF, which aids in muscle-to-brain communication and may promote neurogenesis [210].

In summary, the brain-muscle axis illustrates how skeletal muscle communicates with the brain through various signaling pathways, including the secretion of myokines like Amyrel and BDNF, as well as metabolites like kynurenine. These signals impact brain functions such as neurogenesis, mood regulation, and protection against age-related cognitive decline. Physical exercise enhances these interactions by promoting beneficial molecular changes in muscle that positively affect brain health.

New strategies for treating depression

Anti-inflammatory therapy

Given the strong link between MDD and inflammation, numerous studies have investigated whether anti-inflammatory medications could have antidepressant effects [22, 211,212,213]. Treatment strategies for depression based on body-brain communication focus on targeting the pathways connecting peripheral organs—such as the spleen, liver, lungs, muscles, and gut—to the brain. These approaches include modulating the gut microbiota to influence brain function through the gut-brain axis, utilizing liver-derived metabolites for their anti-inflammatory and neuroprotective effects, and stimulating vagus nerve activity to improve mood and reduce anxiety. Exercise-induced myokines like BDNF and metabolites such as kynurenine are also being explored for their potential to enhance neurogenesis and regulate mood through the brain-muscle axis. By targeting immune and signaling pathways between the body and brain, these therapies offer new avenues for addressing both the physical and mental aspects of depression.

The activation of inflammatory pathways in the brain can result in the upregulation of cyclooxygenase (COX), suggesting that COX inhibition may serve as a therapeutic approach for depression [214]. Preclinical studies have shown encouraging outcomes with selective COX-2 inhibitors such as celecoxib. For example, in a chronic stress rat model, celecoxib (16 mg/kg for 21 days) effectively alleviated depression-like behavior [215]. Similarly, in another depression model, a combination of celecoxib and bupropion (3 mg/kg) reduced depression-like behavior in mice with inflammation induced by complete Freund’s adjuvant, with higher doses of celecoxib (30 mg/kg) showing similar efficacy [216]. Recent studies have shown that celecoxib (10, 20, or 30 mg/kg) in combination with cannabidiol (30 mg/kg) produced synergistic effects in depression models induced by LPS or CSDS. Additionally, a review suggested that celecoxib may help overcome multidrug resistance in humans, with a systematic review of 44 studies reporting that adjunctive treatment with 400 mg/day for six weeks was effective in managing treatment-resistant depression [217, 218].

While these findings are encouraging, clinical studies have not yet clearly linked celecoxib’s antidepressant effects with reduced inflammation, highlighting the need for further research, particularly regarding long-term safety. Non-COX selective agents, like ibuprofen, have produced mixed results. In some studies, ibuprofen (40 mg/kg) alone or combined with escitalopram (10 mg/kg) reversed depression-like behaviors in chronic stress models [219]. However, in other cases, ibuprofen (1 mg/mL) diminished the efficacy of antidepressants like citalopram, fluoxetine, and imipramine [220]. Similarly, ibuprofen (40 mg/kg) failed to prevent depression-like behaviors in endotoxin-treated mice [221]. Acetylsalicylic acid has also produced mixed results. While low doses (45 mg/kg) combined with fluoxetine (5 mg/kg) reversed depressive behaviors in chronic models [222, 223], other studies found that it reduced the effects of citalopram [220]. A recent systematic review highlighted the safety and efficacy of low-dose acetylsalicylic acid for mood disorders, although long-term clinical trials are needed to assess its effectiveness and safety in treating recurrent depression [224].

Anesthetic ketamine has demonstrated rapid-onset and sustained antidepressant effects in treatment-resistant patients with MDD, marking a breakthrough in mood disorder research [225]. Ketamine consists of two enantiomers, (R)-ketamine (arketamine) and (S)-ketamine (esketamine), both of which have potent anti-inflammatory properties [109]. Esketamine, approved for clinical use as an intranasal treatment, works by modulating glutamatergic signaling through NMDA receptor antagonism. Arketamine shows promise for longer-lasting antidepressant effects with fewer dissociative side effects [109, 226]. Emerging evidence suggests that the gut-brain and gut-spleen axes may contribute to arketamine’s antidepressant effects in models of CSDS [108, 131, 132]. Both enantiomers are being investigated for their ability to enhance synaptic plasticity and reduce inflammation, with ongoing research aimed at optimizing their therapeutic use in depression.

Hormone therapy

The most compelling evidence for targeting the HPA axis in depression treatment is the use of GR antagonists, which can alleviate psychiatric symptoms of depression [227]. Other HPA-axis-focused approaches, such as cortisol synthesis inhibitors, glucocorticoids, and vasopressin receptor antagonists, have undergone clinical trials but have shown limited success. Preclinical studies suggest that anxiety and depression-like behaviors can be triggered by chronic renal failure or central injections in brain regions like the amygdala, but these effects can be reduced with CRFR1 antagonists [228,229,230].

Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), a pituitary hormone that stimulates the thyroid gland to produce thyroxine and triiodothyronine, has been linked to the regulation of lipid metabolism via body-brain communication. This regulation has potential implications for both lipid metabolism disorders, such as obesity, and neuropsychiatric disorders, including depression [231]. Targeting the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis, triiodothyronine (T3) has shown clinical efficacy as an adjunct treatment for patients with MDD who do not respond adequately to antidepressants alone. This approach is supported by guidelines from organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association, the Canadian Mood and Anxiety Treatment Network, and the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry, which recommend thyroid hormone supplementation when antidepressant monotherapy is insufficient [232, 233]. Additional research is required to assess the effectiveness of T3 in combination with SSRIs for treatment-resistant depression, ideally through rigorous placebo-controlled trials.

Additionally, oxytocin, a neuropeptide that acts as a neuromodulator in brain regions linked to stress-related disorders, is emerging as a promising candidate for MDD treatment. Oxytocin administration has shown significant antidepressant effects in various behavioral domains in rodent models [234, 235]. Preclinical studies suggest that social isolation in mice reduces cortical IL-1β expression and leads to depression-like behavior, which can be alleviated by oxytocin. In contrast, blocking oxytocin receptors in paired animals leads to depression-like behaviors and elevated IL-1β levels in the frontal cortex [236]. Clinical studies have found lower circulating oxytocin levels in patients with MDD, with negative correlations to the severity of depressive symptoms [237, 238]. Despite its potential, further research is necessary to fully elucidate oxytocin’s role in immune function and its therapeutic potential for depression.

In summary, hormone therapy for depression primarily targets the HPA and HPT axes. GR antagonists and thyroid hormone supplementation, particularly T3, have shown promise for patients unresponsive to standard antidepressants. Oxytocin, with its neuromodulatory effects, also holds potential as a therapeutic option, though further studies are required to clarify its role.

Conclusions and future directions

Emerging research on the central-peripheral neuroimmune axis during psychological stress has uncovered novel therapeutic strategies for treating depression. These strategies target peripheral systems—including the brain-bone marrow, brain-spleen, brain-gut, brain-adipose, brain-heart, brain-liver, brain-lung, and brain-muscle axes—and emphasize the importance of integrating peripheral organ systems into our understanding of depression. This approach moves beyond traditional brain-centered views toward a more comprehensive brain-body framework.

A transdiagnostic perspective further differentiates psychological stress from depression. Stress is seen as a non-specific risk factor that increases vulnerability to various psychiatric disorders, whereas depression is recognized as a distinct clinical syndrome with specific diagnostic criteria. Psychological stress initiates a cascade of neurobiological changes—altering the HPA axis, immune responses, and neurotransmitter systems—that may predispose individuals to depression. However, stress alone does not ensure the development of depression; factors such as genetic predispositions, early-life experiences, and individual resilience also play critical roles. This perspective underscores the need to address common underlying mechanisms across mental health conditions while accounting for the unique features of depression.

Ongoing clinical trials and emerging therapies are increasingly targeting brain-body communication to treat psychiatric disorders. Cytokine blockers, for instance, are under investigation for their potential to reduce systemic and neuroinflammation by neutralizing pro-inflammatory cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α, which are often elevated in depression [239]. At the same time, probiotics and prebiotic interventions are being explored to restore gut microbiota balance, improve neurogenesis, and mitigate neuroinflammation via the gut-brain axis [116, 117, 136, 240]. Additional approaches include immune-modulatory compounds and neuromodulation techniques that target autonomic pathways, all of which represent a promising shift from traditional brain-centric treatments towards more integrated, holistic strategies for managing psychiatric conditions.

Future research should prioritize rigorous clinical trials to assess the long-term efficacy and safety of anti-inflammatory compounds, especially in combination with current antidepressant treatments. In addition, a deeper exploration of the gut-brain and gut-spleen axes, along with inflammation-based therapeutic approaches, may yield valuable insights into depression treatment. Understanding how peripheral organs influence brain function will be essential for optimizing these therapies and paving the way for more personalized and holistic approaches to managing depression. By further elucidating body-brain communication, future studies could unlock innovative treatment options that address both the psychological and physical aspects of depression.

Change history

17 July 2025

The original online version of this article was revised: In this article, the order in which the authors appeared in the author list was incorrectly given as Xiao Feng, Min Jia, Meng Cai, Tong Zhu, Jian-Jun Yang and Kenji Hashimoto where it should have been Xiao Feng, Min Jia, Meng Cai, Tong Zhu, Kenji Hashimoto & Jian-Jun Yang. The original article has been corrected.

15 September 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41380-025-03121-x

References

Hashimoto K, Yang C. Special issue on “Brain-body communication in health and diseases”. Brain Res Bull. 2022;186:47–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2022.05.014

Hashimoto K, Wei Y, Yang C. Special issue on “A focus on brain-body communication in understanding the neurobiology of diseases”. Neurobiol Dis. 2024;201:106666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2024.106666

Furlan A, Petrus P. Brain-body communication in metabolic control. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2023;34:813–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2023.08.014

Sammons M, Popescu MC, Chi J, Liberles SD, Gogolla N, Rolls A. Brain-body physiology: local, reflex, and central communication. Cell. 2024;187:5877–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2024.08.050

Herman JP, McKlveen JM, Ghosal S, Kopp B, Wulsin A, Makinson R, et al. Regulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical stress response. Compr Physiol. 2016;6:603–21. https://doi.org/10.1002/cphy.c150015

Leistner C, Menke A. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and stress. Handb Clin Neurol. 2020;175:55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-64123-6.00004-7

Padgett DA, Glaser R. How stress influences the immune response. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:444–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00173-x

Webster Marketon JI, Glaser R. Stress hormones and immune function. Cell Immunol. 2008;252:16–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cellimm.2007.09.006

Silverman MN, Sternberg EM. Glucocorticoid regulation of inflammation and its functional correlates: from HPA axis to glucocorticoid receptor dysfunction. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2012;1261:55–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06633.x

GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137–50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(21)00395-3

Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9:46–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn2297

Dantzer R. Neuroimmune interactions: from the brain to the immune system and vice versa. Physiol Rev. 2018;98:477–504. https://doi.org/10.1152/physrev.00039.2016

Hodes GE, Kana V, Menard C, Merad M, Russo SJ. Neuroimmune mechanisms of depression. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18:1386–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4113

Menard C, Pfau ML, Hodes GE, Kana V, Wang VX, Bouchard S, et al. Social stress induces neurovascular pathology promoting depression. Nat Neurosci. 2017;20:1752–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41593-017-0010-3

Oines E, Murison R, Mrdalj J, Grønli J, Milde AM. Neonatal maternal separation in male rats increases intestinal permeability and affects behavior after chronic social stress. Physiol Behav. 2012;105:1058–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physbeh.2011.11.024

Howes OD, Khambhaita A, Fusar-Poli P. Julius Wagner-Jauregg, 1857–940. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:409. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08081271

Dowlati Y, Herrmann N, Swardfager W, Liu H, Sham L, Reim EK, et al. A meta-analysis of cytokines in major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:446–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.09.033

Howren MB, Lamkin DM, Suls J. Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosom Med. 2009;71:171–86. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b

Liu Y, Ho RC, Mak A. Interleukin (IL)-6, tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and soluble interleukin-2 receptors (sIL-2R) are elevated in patients with major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and meta-regression. J Affect Disord. 2012;139:230–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.003

Köhler CA, Freitas TH, Maes M, de Andrade NQ, Liu CS, Fernandes BS, et al. Peripheral cytokine and chemokine alterations in depression: a meta-analysis of 82 studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135:373–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12698

Maes M, Yirmyia R, Noraberg J, Brene S, Hibbeln J, Perini G, et al. The inflammatory & neurodegenerative (I&ND) hypothesis of depression: leads for future research and new drug developments in depression. Metab Brain Dis. 2009;24:27–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11011-008-9118-1

Miller AH, Maletic V, Raison CL. Inflammation and its discontents: the role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:732–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.029

Stewart JC, Rand KL, Muldoon MF, Kamarck TW. A prospective evaluation of the directionality of the depression-inflammation relationship. Brain Behav Immun. 2009;23:936–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2009.04.011

Papakostas GI, Shelton RC, Kinrys G, Henry ME, Bakow BR, Lipkin SH, et al. Assessment of a multi-assay, serum-based biological diagnostic test for major depressive disorder: a pilot and replication study. Mol Psychiatry. 2013;18:332–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2011.166

Kiraly DD, Horn SR, Van Dam NT, Costi S, Schwartz J, Kim-Schulze S, et al. Altered peripheral immune profiles in treatment-resistant depression: response to ketamine and prediction of treatment outcome. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:e1065 https://doi.org/10.1038/tp.2017.31

Syed SA, Beurel E, Loewenstein DA, Lowell JA, Craighead WE, Dunlop BW, et al. Defective inflammatory pathways in never-treated depressed patients are associated with poor treatment response. Neuron. 2018;99:914–24.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2018.08.001

Hepgul N, Cattaneo A, Zunszain PA, Pariante CM. Depression pathogenesis and treatment: what can we learn from blood mRNA expression? BMC Med. 2013;11:28 https://doi.org/10.1186/1741-7015-11-28

Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1696–709. https://doi.org/10.1038/mp.2016.3

Maes M, Song C, Lin A, De Jongh R, Van Gastel A, Kenis G, et al. The effects of psychological stress on humans: increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and a Th1-like response in stress-induced anxiety. Cytokine. 1998;10:313–8. https://doi.org/10.1006/cyto.1997.0290

Raison CL, Broadwell SD, Borisov AS, Manatunga AK, Capuron L, Woolwine BJ, et al. Depressive symptoms and viral clearance in patients receiving interferon-alpha and ribavirin for hepatitis C. Brain Behav Immun. 2005;19:23–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2004.05.001