Abstract

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) lacks a standardized classification system, resulting in inconsistent clinical management and a suboptimal prognosis. This study addresses the urgent need for a robust consensus taxonomy to facilitate precision treatment for ESCC. We employed a network-based approach to elucidate the interconnections among eight existing classification systems, leading to the identification of four distinct consensus molecular subtypes (ECMSs): ECMS1-MET (metabolic), characterized by dysregulated metabolic pathways and NFE2L2 activation; ECMS2-CLS (classical), featuring upregulated cell cycle and canonical signaling pathways; ECMS3-IM (immunomodulatory), marked by robust immune activation and elevated PD-1 expression; and ECMS4-MES (mesenchymal), associated with mesenchymal transition, stromal activation, and VEGF signaling. To improve clinical applicability, we developed an image-based framework (imECMS) that utilizes spatial organization features (SOFs) quantified from autodelineated hematoxylin‒eosin (H&E)-stained whole-slide images through deep learning algorithms. The imECMS classifier assigns patients to one of the four ECMS subtypes, which correlate with distinct molecular characteristics, prognoses, and responses to neoadjuvant chemotherapy and immunotherapy. Validation across multiple independent cohorts confirmed that the imECMS accurately classifies ESCC subtypes from histopathological images, offering a robust and effective tool for precision medicine. In summary, the ECMS/imECMS subtyping systems we developed are the most robust frameworks for ESCC to date, providing clear biological insights and a foundation for clinical stratification and targeted therapies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Molecular subtyping has been widely adopted as a cornerstone in dissecting tumor heterogeneity and advancing precision cancer medicine over recent decades.1,2,3,4,5,6 Recent studies highlighted integrative analyses of multiomics profiles, including genomics, transcriptomics, epigenomics, proteomics, and metabolomics, which significantly deepened our understanding of cancer heterogeneity and led to more comprehensive classifications.7,8 This advancement has been applied to various major malignancies, such as colorectal cancer, breast cancer, bladder cancer, lung cancer, and B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, with precision treatment strategies tailored to different molecular subtypes, benefiting more patients, improving outcomes, and reducing unnecessary treatments and side effects.6,9,10,11,12,13 Moreover, consensus molecular subtyping has been demonstrated to be an efficient strategy for reconciling multiple independent studies and generating a standardized taxonomy, ensuring consistency and reproducibility in clinical settings. These consensus subtyping systems have refined prognostic and predictive markers, fostering the development of personalized treatment strategies.14,15,16

Esophageal squamous cell carcinoma (ESCC) is a highly aggressive malignancy with a typically unfavorable prognosis, posing major challenges in clinical management. Despite recent declines in incidence and mortality resulting from reduced exposure to risk factors and enhanced screening, ESCC continues to pose a significant healthcare burden because of its low survival rates and limited targeted therapies.17,18,19,20,21 Recent efforts have produced seven subtyping systems based on the clustering of molecular features of ESCC,9,18,20,22,23,24,25 revealing its complex heterogeneity and diverse subtypes with varying biological and clinical characteristics. However, most of the existing ESCC subtyping systems are derived from a single type of omics data, such as copy number variation (CNV),25 single-nucleotide variants (SNVs),18 and gene expression profile data,22,23,24 ignoring potential heterogeneity at other omics levels. More importantly, these preexisting subtyping efforts are hindered by inconsistent conclusions, which may arise from differences in the discovery dataset, classification methods, and biological interpretations. The subtyping system COCA, recently proposed by our team,9 demonstrated strong predictive value for the immunotherapy response. However, COCA is based on a decision-layer integration of subtyping results, which may overlook potential interactions between different types of omics profiles. Thus, there remains an unmet need to elucidate the interconnections between existing ESCC taxonomies and to define consensus molecular subtypes in a rigorous, unbiased manner.

Histopathology images contain rich information about the cell morphologies and tissue architectures characterizing the tumor microenvironment (TME) in relation to molecular subtype-specific properties. These widely available imaging resources have made it possible to develop cost-efficient and easily accessible tools for patient stratification in clinical practice. The hand-crafted characteristics defined by pathologists’ review of histopathological images, such as the relative ratios of tumor-infiltrating immune, stroma, and inflammatory cells,26,27,28,29 have been exploited. Recently, deep learning has significantly extended the capabilities of traditional pathology. The “deep features” learned from various neural networks have been employed to develop diagnostic,30,31,32 prognostic33,34 and treatment response models.35,36 Furthermore, deep learning-empowered digital pathology can also map image-based features to molecular characteristics such as gene mutations,37,38 pathways,39,40 microsatellite instability,39,41 and even molecular subtypes.28,42 For example, Korsuk et al. demonstrated the efficacy of multimodal data, including H&E images, in constructing a consensus molecular typing system for colorectal cancer.43 Combining imaging modalities with other omics and clinical data enhances tumor classification accuracy and streamlines clinical implementation, which is essential for personalized therapeutics.

In this study, we first investigated complex heterogeneity via multiomics ESCC subtyping (MESCC) via a feature-layer integration method, overcoming the potential loss of interaction information inherent in decision-layer methods.44 Decision-layer integration combines single-omics clustering results but ignores interomics interactions. Our feature-layer fusion instead integrates single-omics similarity matrices, preserving both omics-specific features and cross-omics relationships for the final classification. To address the inconsistencies between the eight ESCC classifications, including MESCC, we employed a network-based approach to systematically elucidate their statistical associations. The resulting subtype association network demonstrated strong interconnectivity, consolidating them into four robust consensus molecular subtypes (ECMSs). Each ECMS is characterized by distinct molecular features and clinical properties, offering biologically meaningful insights and advancing translational potential. Furthermore, to provide cost-efficient and easily accessible tools for clinical practice, we developed an image-based classifier, imECMS, on the basis of multiscale spatial organization features (SOFs) quantified through deep learning of H&E-stained whole-slide images (WSIs). Overall, the ECMS and imECMS represent the most robust classification systems currently available for ESCC, laying a foundation for future clinical stratification and subtype-based targeted interventions.

Results

Consensus molecular subtyping of ESCC

Seven independent ESCC subtyping systems have been developed via distinct discovery datasets and bioinformatics methods (Supplementary Data 1).9,18,22,23,24,25,45 These studies investigated the heterogeneity in SNVs,18 CNVs,25 or gene expression profiles,22,23,24 resulting in single-omics subtypes41,46,47 or combined subtypes by decision‒layer integration.9 To better dissect the collective heterogeneity observed at different omics levels, we employed similarity network fusion (SNF) for feature-layer multiomics subtyping (Supplementary Fig. 1a, details in “Methods”). As a result, we identified four robust multiomics ESCC subtypes (MESCC1–4, Supplementary Fig. 1b), demonstrating that MESCC captured coherent substructures that were not evident in the single-omics data (Supplementary Fig. 1b, c). MESCC4 patients had significantly poorer overall survival (OS, P = 0.017) and disease-free survival (DFS, P = 0.016) than other subtypes did (log-rank tests, Supplementary Fig. 1d). To examine the associations between the MESCC and the seven preexisting classification systems, we next sought to compare their subtyping results on the same multiomics dataset. To this end, we employed our in-house SXM-I cohort (Shanxi Medical Cohort I), which is a multiomics cohort including RNA-seq, whole-genome sequencing (WGS), and whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) data for 152 ESCC patients (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Data 2). Hypergeometric tests confirmed significant associations across different subtyping systems, suggesting that the MESCC system and the other subtyping systems are highly interconnected rather than isolated (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Identification of the consensus molecular subtypes of esophageal squamous cell carcinomas. a Schematic workflow for subtype classification of the SXM-I cohort using eight ESCC subtyping systems. b Network illustrating the interconnections between 25 subtypes of the eight existing taxonomies. Each node represents a subtype colored according to the corresponding classification system, with the size proportional to the sample size. Edge width denotes the association between two subtypes, quantified by consensus frequency. Four consensus subtypes (ECMS1–4) were identified via the Markov cluster algorithm. (CNV1–3: CNV-based subtypes 1–3 from Du et al.; NMF1–3: SNV-based subtypes 1–3 from Cui et al.; CU1–3: transcriptome-based subtypes 1–3 from Liu et al.; Subtypes 1–2: transcriptome-based subtypes 1–2 from Wang et al.; Oncotargets 1–4: transcriptome-based subtypes 1–4 from Xiong et al.; TCGA1–2: transcriptome-based subtypes 1–2 from TCGA-ESCC; MESCC1–4: Multiomics subtypes 1–4 from our study. COCA1-4: Multiomics subtypes 1–4 from COCA.)

The eight subtyping systems, including the MESCC, identified different numbers of subtypes, ranging from two to four, with biological interpretations from different perspectives. These discrepancies have led to significant confusion and hindered practical implementation. To address this challenge, we employed a computational workflow previously developed for colorectal cancer.48 More specifically, we used a network-based approach16 to systematically investigate the associations between the 25 subtypes from the eight ESCC subtyping systems. As a result, we generated a network of statistical associations on the basis of hypergeometric tests, with repeated subsampling of 85% of patient samples from the SXM-I cohort. This network was partitioned into clusters via the Markov cluster algorithm (MCL), repeated 100 times, and aggregated into a consensus matrix capturing the frequency of subtype coclustering (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Clustering the consensus matrix with MCL revealed four robust consensus molecular subtypes (or “ECMS1–4”, Fig. 1b). Interestingly, subtypes within the same consensus molecular subtype exhibited strong associations and similar biological properties. For example, poor prognosis subtypes such as MESCC4, OncoTarget4, and Subtype2 were unified within ECMS4. ECMS2 aligned with dysregulated classical pathways previously observed in CU3, TCGA1, and OncoTarget1 (Supplementary Fig. 2b–i). Notably, the MESCC subtypes were mapped distinctly to each ECMS category (Supplementary Fig. 2i, Supplementary Fig. 3). These findings demonstrated that the eight subtyping systems are highly interconnected and can be consolidated into four robust consensus molecular subtypes, providing a unified taxonomy for clinical and biological applications.

To facilitate transcriptomic classification, we developed a classifier using gene expression profiles that are most representative of each consensus molecular subtype in the SXM-I cohort. A random forest classifier was trained with differentially expressed genes to differentiate each ECMS subtype. This classifier successfully assigned 476 samples from the SXM-I, TCGA-ESCC, GSE53625, GSE45670, and immune checkpoint blockade (ICB; an RNA-seq cohort of 39 patients treated with anti-PD-1 therapy) cohorts to the four ECMS subtypes (Supplementary Data 2 and 3).

Multiomics molecular characterization of ECMSs

Having identified the four ECMSs, we next sought to delineate the biological properties specific to each subtype. We first investigated genomic variations, focusing on somatic SNVs and somatic copy number variations (SCNVs) (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Data 4 and 5). Consistent with previous studies, the most frequently altered genes were TP53 (91%), followed by CDKN2A (84%), NFE2L2 (48%), KMT2C (39%), KMT2D (30%), NOTCH1 (18%), CSMD3 (16%), PIK3CA (14%) and LRP1B (12%).45,49 Notably, CDKN2A and FAT1 were predominantly associated with deletion events, whereas NFE2L2 exhibited frequent amplifications. Specifically, NFE2L2 amplifications were more prevalent in ECMS1 (P < 0.01, 22/32 vs 44/120, chi-square test, Supplementary Data 5), which aligns with its higher expression levels (Fig. 2b). Conversely, ECMS3 tumors presented fewer SCNV events (Fig. 2c, Supplementary Fig. 4a) and lower tumor mutation burdens (TMBs) (Fig. 2d), which recapitulated the CNV2 subtype described by Du et al.25 Furthermore, nonsilent mutations in KMT2D were associated with a poor prognosis50; however, such mutations were notably less frequent in ECMS3 (Fig. 2e).

Molecular characterization of the ECMS subtypes. a Landscape of the genomic profiles of the 152 ESCC patients in the SXM-I cohort. Comparisons of key genomic and epigenomic markers, including b NFE2L2 expression levels, among the four consensus subtypes, c SCNA segment count, d tumor mutation burden, e KMT2D mutation count, and f DNA methylation level of the BST2 promoter. g Boxplot showing the distribution of the miR-205-5p promoter methylation level across ECMSs. h Heatmap illustrating gene set enrichment analysis of canonical pathways, gene signatures, metabolic pathways, immune signatures, and immune and stromal infiltration signatures that are of special interest in ESCC. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests)

Comparing the top 15 mutated genes between the TCGA-ESCC dataset and two Chinese ESCC cohorts, SXM-I and SXM-II (Shanxi Medical Cohort II, a WGS cohort with 396 ESCCs) (Supplementary Fig. 5 and Supplementary Data 2), we found that TP53 mutations were consistently prevalent, and no significant difference was observed between the datasets (P = 0.22). In contrast, CDKN2A and FAT1 mutations were significantly more common in the Chinese cohort than in the TCGA-ESCC cohort (P = 0.0019 and 0.046, respectively, chi-square tests), whereas NFE2L2 mutations were less common in the Chinese cohort (P = 0.045, chi-square test). Previously, we identified a subtype in the SXM-I cohort, COCA2, characterized by NFE2L2 activation, which aligns with our present finding of NFE2L2 activation in ECMS1 (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2h).

Next, differential analyses were performed on the mRNA expression, miRNA expression, and DNA methylation profiles, revealing significant heterogeneity among the four ECMS subtypes and subtype-specific multiomics signatures (Supplementary Fig. 4b–d, Supplementary Data 6–8). ECMS2 tumors display a widespread hypomethylation status (Supplementary Fig. 4d, Supplementary Data 7). Of particular interest is the immunomodulatory molecule BST2, which was identified as subtype-specific in the TCGA study.45 The TCGA2 subtype is associated with less promoter methylation and higher expression of BST2, suggesting the potential for epigenetic silencing of BST2. In our study, BST2 methylation differed between the ECMS subtypes (Fig. 2f), with lower methylation observed in ECMS2, which includes TCGA2. Moreover, hypermethylation of the BST2 promoter significantly suppressed its expression (Supplementary Fig. 6a), which is consistent with the findings of the TCGA study.

Subtype-specific miRNAs were also identified, revealing distinct posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression across subtypes. Notably, the expression of miR-200 family members, which are important for the regulation of epithelial‒mesenchymal transition (EMT),51 is significantly downregulated in ECMS4 but upregulated in ECMS2 (Supplementary Data 8, Supplementary Fig. 6g). ECMS2 samples also presented high expression of miR-205-5p (Fig. 2g, Supplementary Data 8), which was inversely correlated with its promoter methylation (Supplementary Fig. 6b). ZEB1 and ZEB2 are important transcription factors that play crucial roles in regulating EMT in ESCC.52,53 In our study, the expression levels of ZEB1 and ZEB2 in ECMS4 were significantly greater (P = 0.01 and 0.049, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 6c, d), whereas those in ECMS2 samples were the lowest (P = 3.78 × 10−4 and 0.002, respectively; Supplementary Fig. 6c, d). Previous studies have suggested that the miR-200 family and miR-205-5p both regulate tumor migration and invasion by targeting ZEB1 and ZEB2.54,55,56,57 Consistently, we found that the promoter methylation of miR-200a-5p and miR-205-5p was significantly negatively correlated with ZEB1 and ZEB2 expression (Supplementary Fig. 6e, f, h, i).

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was performed to further elucidate the biological underpinnings of each ECMS subtype. As expected, each ECMS subtype exhibited distinct biological processes and pathways (Fig. 2h). ECMS1 is characterized by dysregulation of various metabolic pathways, including those related to cytochrome, glutathione, sucrose, glycoside, and uronic acid. We therefore designated this subtype the metabolic subtype (ECMS1-MET). The involvement of NFE2L2 in metabolic reprogramming58,59,60 likely contributes to the metabolic dysregulation observed in ECMS1-MET. ECMS2 exhibited dysregulation of canonical pathways such as the cell cycle and WNT and MYC signaling pathways, which is consistent with previously described subtypes (CU3, TCGA1, and OncoTarget1), and was thus defined as the classical subtype (ECMS2-CLS). ECMS3 is characterized by robust immune activation (immunomodulatory subtype, ECMS3-IM), as evidenced by the enrichment of inflammatory helper T cells (Th1 and Th17), the JAK-STAT pathway, and elevated PD-1 expression. Finally, ECMS4 displays mesenchymal characteristics, including activation of TGFβ signaling, matrix remodeling, the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) pathway, and EMT, leading to its designation as the mesenchymal subtype (ECMS4-MES). Consistently, we found that the core signature genes for the EMT and VEGF pathways were significantly more highly expressed in ECMS4-MES, whereas the core signature genes for the cell cycle were more highly expressed in ECMS2-CLS compared tothan in the other three subtypes (Supplementary Fig. 7).

To investigate the TME, we computed immune and stromal scores via the deconvolution of bulk-tumor transcriptomic data using ESTIMATE.61 Consistent with our GSEA results, ECMS3-IM tumors presented significantly higher immune scores, whereas ECMS4-MES tumors presented a significantly greater stromal content (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). Both ECMS3-IM and ECMS4-MES exhibited lower tumor purity (Supplementary Fig. 8c), suggesting a greater influence on the TME. Further analysis with Tumor IMmune Estimation Resource (TIMER)62 confirmed increased immune infiltration by B cells and CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in the ECMS3-IM subtype (Supplementary Fig. 8d–i). Proteomic analysis corroborated these findings, with GSEA of proteomic profiles from 90 ESCC samples (from patients in SXM-I) reflecting the molecular characteristics observed at the gene expression level (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Clinical characterization of the ECMS subtypes

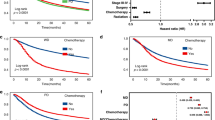

To explore the clinical implications of our ECMS taxonomy, we next investigated the associations between molecular subtypes and clinicopathological characteristics (Fig. 3a). In the SXM-I cohort, patients assigned to the ECMS4-MES group had a greater risk of recurrence (P < 0.05, hypergeometric test, Fig. 3b). ECMS3-IM was significantly overrepresented among patients with a history of heavy alcohol consumption, whereas ECMS4-MES patients were more likely to be nondrinkers (both P < 0.05, hypergeometric tests, Fig. 3c). Furthermore, ECMS4-MES patients had the poorest overall survival (OS) (P = 0.015, log-rank test, Fig. 3d) and DFS (P = 0.029, log-rank test, Fig. 3e). This robust association was further validated in independent cohorts: (1) the ECMS classification maintained strong prognostic value for OS in the GSE53625 cohort (P = 0.0089, Supplementary Fig. 10) and (2) was significantly associated with DFS in the TCGA-ESCC cohort (P = 0.049, Supplementary Fig. 11).

Clinicopathological and prognostic associations of the ECMS subtypes. a Heatmap showing the associations of the four subtypes with typical ESCC clinicopathological characteristics. Barplots comparing the associations between subtypes and b recurrence/metastasis and c drinking history. Kaplan‒Meier analysis for d overall survival and e disease-free survival, showing the prognostic value of the ECMS. f Barplot comparing the response of patients in the four ECMSs to neo-CRT. g Barplot comparing the response of patients in the four ECMSs to ICB. pCR pathological complete response, <pCR less than pCR, PR partial response, SD stable disease, PD progressive disease

We next investigated potential therapeutic strategies tailored to each ECMS subtype by analyzing preclinical drug sensitivity data from the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal (CTRP). The predicted IC50 values for common ESCC chemotherapies revealed subtype-specific sensitivities. ECMS2-CLS, characterized by cell cycle dysregulation, presented lower IC50 values for cisplatin, vinorelbine, paclitaxel, and docetaxel, indicating greater sensitivity, whereas ECMS1-MET and ECMS4-MES were resistant to paclitaxel, and ECMS3-IM was resistant to cisplatin and docetaxel (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Analysis of gene expression patterns and drug target expression revealed additional subtype-specific therapeutic opportunities (Supplementary Fig. 13, Supplementary Data 9). ECMS1-MET cells presented high FGFR2 expression, suggesting sensitivity to FGFR inhibitors such as AZD4547. This finding was supported by a strong correlation between FGFR2 expression and AZD4547 sensitivity in esophageal cancer cell lines (Supplementary Fig. 13b). NTRK2 was also highly expressed in ECMS1-MET (Supplementary Fig. 13a), indicating the potential efficacy of NTRK-targeted therapies (Supplementary Data 9). For ECMS2-CLS, chloride channel blockers and CXCL8-CXCR1/2 inhibitors may be effective because of the high expression of GJB6 and CXCL8. In addition, the high number of cell cycle signals indicates that this subtype may benefit from treatment with CDK inhibitors, which is consistent with our previously published cell cycle subtype.9 ECMS3-IM tumors highly expressed PDCD1 and IDO1 (Fig. 2h, Supplementary Fig. 13a, Supplementary Data 9), which are attractive targets for cancer immunotherapy, suggesting a potential therapeutic strategy involving targeting PD-1 and IDO1 in this subtype. ECMS4-MES consistently expressed high levels of matrix metalloprotease, suggesting potential benefits from matrix metalloprotease inhibitors such as ilomastat and marimastat (Supplementary Data 9). Furthermore, ERBB2 amplification was frequently observed in ECMS2-CLS (Supplementary Fig. 13c, Supplementary Data 5), indicating that HER2-targeted therapeutics may be effective in this subtype.

Two clinical cohorts were analyzed to further evaluate the associations of ECMS subtypes with neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (neo-CRT)63 and immunotherapy responses.64 Notably, none of the ECMS3-IM patients achieved a pathological complete response (pCR) (P = 0.032, hypergeometric test, Fig. 3f and Supplementary Fig. 14a), suggesting a limited benefit from neo-CRT for this particular subgroup. Although not statistically significant, ECMS1-MET was also present in a high proportion of patients with less than pCR (Fig. 3f), potentially due to the high activity of cytochrome P450 in these two subtypes.65,66,67,68,69 Furthermore, we assessed the potential of ECMS subtypes to predict the response to ICB using an anti-PD-1 cohort (ICB cohort) recently published.64 Patients with ECMS3-IM showed a significantly higher rate of partial response (Fig. 3g and Supplementary Fig. 14b, P = 0.044, hypergeometric test), which might be partially explained by the higher expression level of PDCD1 (PD-1) in this subtype (Fig. 2g).

In summary, our comprehensive molecular and clinical analyses underscore the strong biological and clinical relevance of the four ECMSs, highlighting their potential to inform personalized treatment strategies.

Development of a deep learning-based framework to quantify spatial organization features characterizing the ESCC microenvironment

To dissect the TME, we established a robust and efficient deep learning-based framework, ESCC-SPA, leveraging transfer learning techniques from our previous research on colorectal cancer.70 The ESCC-SPA classifier was trained on a dataset comprising 48,376 histological tissue patches manually annotated by a pathologist and validated on an independent set of 3996 tissue patches from different patients (Supplementary Data 10). This framework was capable of classifying image patches into eight distinct regions and tissue types (Fig. 4a), including background (BACK), connective tissue (CON), squamous epithelium (EPI), gland (GLA), lymphocyte (LYM), smooth muscle (MUS), cancer-associated stroma (STR), and tumor (TUM) regions. For the internal validation and independent testing datasets, ESCC-SPA achieved high classification accuracies of 99% and 94%, respectively, with excellent discrimination among tissue types (area under the curve (AUC) ≥ 0.99, Supplementary Fig. 15).

Spatial characterization of the ESCC microenvironment on the basis of deep learning of histological images. a A schematic workflow of ESCC-SPA, including image preprocessing, training, and testing a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) for tissue classification, and calculation of SOFs. Image patches are classified into eight tissue types: tumor (TUM), stroma (STR), lymphocyte (LYM), smooth muscle (MUS), normal epithelium (EPI), gland (GLA), connective tissue (CON), and background (BACK). b Representative examples of image delineation based on tissue classification. (The scale bar for the main overview image represents 2 mm, while the scale bar for the zoomed-in detailed inset represents 0.25 mm). c Distributions of whole-slide SOFs across 152 ESCC patients in the SXM-I cohort. d Boxplots showing that ECMS2-CLS, ECMS3-IM, and ECMS4-MES tumors had significantly higher ratios of tumor tissue, lymphocytes, and stroma. e Scatterplots showing that the image-based tumor, lymphocyte, and stroma indices are significantly correlated with the transcriptome-based immune score, tumor purity, and stromal score. (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Wilcoxon signed-rank tests)

Using the trained ESCC-SPA model, we performed automated delineation of H&E-stained WSIs in all cohorts. The tissue classification results for all image patches within each WSI were compiled, with distinct colors representing different tissue types. For morphological assessment, we visualized three representative cases from the SXM-I cohort to demonstrate the tissue architecture present in the WSIs. (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 16). Consistent distributions of different tissue types were observed across all cohorts, of which tumor (TUM) tissues were the most prevalent, suggesting that H&E images provide informative and reliable features for subsequent analyses (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Fig. 17).

Next, we investigated whether the four ESCC subtypes presented distinct SOFs reflective of their molecular properties. To this end, we evaluated the relative abundance of various tissue types in the WSIs and analyzed their distributions, stratified by ESCC subtype within the SXM-I cohort (Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 18). Interestingly, we found that ECMS3-IM tumors presented significantly greater proportions of lymphocytes, glands, smooth muscle and normal epithelium (all P < 0.05, one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank tests, Fig. 4d and Supplementary Fig. 18c). Conversely, ECMS1-MET and ECMS2-CLS tumors were characterized by a greater fraction of tumor tissue (P < 0.05, Fig. 4d), and ECMS4-MES tumors had greater stroma content (P < 0.05, Fig. 4d). These observations were also consistent with the tumor purity and immune and stromal scores obtained from ESTIMATE61 analysis of the bulk-tumor gene expression profiles (Supplementary Fig. 8a, c). A significant correlation, yet modest in the magnitude of the coefficients, was observed between the overall SOFs and ESTIMATE scores, suggesting potential associations between image-based spatial features and molecular characteristics (all P < 0.05, Spearman correlation tests, Fig. 4e).

Development and evaluation of a histology image-based ECMS classifier

A significant barrier to the widespread adoption of molecular subtyping is the prohibitive cost of high-throughput sequencing. Histopathological images derived from tissue slides offer a cost-effective and easily accessible assay to overcome this limitation.71,72,73,74 To bridge this gap, we developed a histological image-based classification system (imECMS) to translate our ECMS taxonomy into a clinically applicable tool. More specifically, we employed a multiscale quantification approach to derive SOFs from H&E-stained histological images at varying magnifications (e.g., 5×, 10×, 20×) based on the tissue classification results (Fig. 5a). As a result, a total of 317 SOFs were obtained for all cohorts with H&E images (details in “Methods,” Supplementary Data 12, 14 and 15).

Histological image-based classification of ESCC subtypes. a A schematic figure illustrating the multiscale geospatial characterization of the ESCC microenvironment on the basis of histological images. b ROC curves showing the performance of our image-based classifier for subtype prediction. c KM plot showing the associations between the predicted subtypes via the image-based classifier and OS in the SXM-I cohort. d Patient-level distribution matrix comparing molecular and image-based subtype predictions in the discovery cohort (SXM-I). e ROC curves showing the performance of our image-based classifier for subtype prediction in the SXM-III cohort. f Heatmap illustrating a confusion matrix comparing molecular and image-based subtype predictions in the SXM-III cohort. g KM plot showing the associations between the predicted subtypes via the image-based classifier and OS in the SXM-II cohort. (p value: log-rank test)

To build a robust classifier, we selected 106 patients representative of ECMS subtypes, with a total of 340 tissue slides after filtering out outlier H&E slides, as our training set (details in “Methods” and Supplementary Fig. 19). An image-based classifier (imECMS) was built via extremely randomized trees,75 which are based on the SOFs, to predict the four ECMS subtypes. imECMS achieved an AUC greater than 0.80 for each subtype, as determined through 10-fold cross-validation repeated 100 times (Fig. 5b). The imECMS was subsequently evaluated for clinical associations using the entire SXM-I cohort (152 patients with 626 slides) and the SXM-II cohort (326 patients with 1157 slides). Patient stratification based on the imECMS was significantly associated with OS and DFS in the SXM-I cohort (P = 0.021 and P = 0.038, respectively; Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 20). The imECMS classification demonstrated high concordance with the ECMS subtyping result (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 21) and was significantly associated with OS in the independent SXM-II cohort (P = 0.034, Fig. 5g). To validate the efficacy of imECMS, we prospectively recruited an additional cohort (SXM-III, details in “Methods”) of 32 patients (with eight patients selected per imECMS subtype based on H&E image predictions) for transcriptomic profiling. The results revealed robust predictive performance, with AUC values ranging from 0.8–0.9 across all four subtypes (Fig. 5e). The imECMS classification demonstrated significant concordance with the ECMS subtypes (Fig. 5f), further suggesting that our imECMS model effectively predicts the ECMS subtypes in ESCC. In addition, to elucidate which SOFs contribute to subtype predictions, we identified the most significant SOFs for each subtype (details in “Methods” and Supplementary Data 10 and 11). Notably, these top-ranked SOFs (Supplementary Fig. 22 and Supplementary Data 13) recapitulated the molecular characteristics associated with each ECMS subtype (Fig. 2g). Overall, our results demonstrated the strong potential of the use of histological images that are widely available in the clinic for effective molecular subtyping of ESCC.

Discussion

Recent studies have significantly advanced our understanding of the molecular heterogeneity and classification of ESCC. However, preexisting subtyping systems are hindered by discordant results due to variations in datasets, algorithms, and perspectives of biological interpretations, limiting their utility for prognosis prediction and personalized treatment. To address these challenges, we established a consensus molecular classification system to characterize the molecular features of ESCC comprehensively and improve patient stratification. Using a network-based approach previously developed for colorectal cancer,48 we analyzed eight ESCC taxonomies, identifying four consensus molecular subtypes (ECMSs) with distinct biological characteristics and therapeutic implications (Table 1, Fig. 6). The ECMS framework standardizes patient classification, improving the accuracy and reproducibility of subtype identification. To further support clinical implementation, we developed a histology image-based classification system (imECMS), which closely correlates with molecular features (Fig. 6). By integrating molecular profiles and microenvironmental architecture, these systems hold promise for advancing personalized medicine and improving outcomes for ESCC patients.

Therapeutic strategies based on the proposed ECMS taxonomy. The ECMS framework enables precision medicine and clinical translation via a histopathology-based classifier, imECMS. ECMS1/imECMS1-MET exhibits metabolic dysregulation and NFE2L2 activation, indicating sensitivity to NFE2L2 inhibitors, FGFR inhibitors, and NTRK-targeted therapies. ECMS2/imECMS2-CLS, characterized by cell cycle upregulation, may respond to HER2-targeted therapies, chloride channel blockers, and CXCL8 inhibitors. ECMS3/imECMS3-IM, which is characterized by immune activation and EMT, is resistant to chemotherapy but has a greater response to immune checkpoint blockade. ECMS4/imECMS4-MES, with VEGF and EMT pathway activation, may benefit from angiogenesis inhibitors and matrix metalloprotease inhibitors. This figure was created using Adobe Illustrator

Each ECMS subtype exhibits unique therapeutic vulnerabilities. ECMS1-MET tumors are characterized by the dysregulation of multiple metabolic pathways, alongside the activation of the transcription factor NFE2L2, suggesting that targeting NFE2L2 and its associated oncogenic pathways could benefit patients with this subtype. Additionally, the high expression of FGFR2 in ECMS1-MET indicates sensitivity to FGFR inhibitors, such as AZD4547, whereas elevated NTRK2 expression highlights the potential efficacy of NTRK-targeted therapies. ECMS2-CLS represents a classical subtype defined by the upregulation of key cellular processes, particularly the cell cycle pathway, which is consistent with our previous finding that targeting the cell cycle may be effective in this subtype.9 The high expression of GJB6 and CXCL8 suggests that chloride channel blockers and CXCL8-CXCR1/2 inhibitors may be alternative effective therapeutic options for this subtype. Moreover, the frequent amplification of ERBB2 in ECMS2-CLS patients indicates that HER2-targeted therapies could be particularly effective in these patients. ECMS3-IM is notable for its strong immune activation and EMT. In silico analysis revealed resistance to both cisplatin and docetaxel in this subtype (Supplementary Fig. 11), which is consistent with findings from a neo-chemoradiotherapy (neo-CRT) cohort in which ECMS3-IM patients failed to achieve pCR. These data suggest limited benefit from conventional chemoradiotherapy in ECMS3-IM patients. However, ICB therapy was associated with significantly higher partial response rates in ECMS3-IM patients, potentially due to elevated PDCD1 (PD-1) expression. These findings suggest that patients with ECMS3-IM tumors may benefit more from immunotherapy than from traditional chemotherapy. Finally, the ECMS4-MES subtype is characterized by the upregulation of VEGF-related pathways and the EMT pathway, which are associated with poor overall and DFS. Our study revealed significantly high expression of VEGF family genes in this subtype, suggesting that patients with this subtype may benefit from therapies targeting angiogenesis and EMT-related molecules, including matrix metalloprotease inhibitors such as ilomastat and marimastat. Compared with multiomics data, H&E-stained histological slides are widely available and cost-effective, making them an attractive alternative for clinical applications. We developed a deep learning-based framework for tissue classification, which revealed a strong correlation between histopathology-derived SOFs (e.g., tumor, lymphocyte, and stromal contents) and transcriptomic data, demonstrating that histopathology slides can partially reflect molecular heterogeneity. Building on this framework, we developed an image-based subtype classifier for clinical translation. This classifier accurately mapped ESCC patients to ECMS subtypes, which are significantly associated with potential treatment strategies and overall survival. To further validate its efficacy, we prospectively recruited an independent cohort for H&E histological image analysis and RNA-seq, which confirmed the strong predictive performance and significant concordance between the imECMS and ECMS classifications. By enhancing the accessibility and convenience of subtype classification, this image-based system holds great potential for improving the clinical applicability of ESCC molecular subtyping.

While our study provides valuable insights, certain aspects warrant further investigation. The relatively small cohort size, which is primarily constrained by the substantial costs associated with multiomics sequencing and the scarcity of publicly available multiomics data for ESCC, may impact the robustness of the computational model. This further underscores the importance of validation in larger, diverse, and prospective ESCC cohorts. Additionally, the SOFs offered promising correlations but could benefit from further in-depth analysis and the integration of multimodal data to enhance their characterization. Although this study did not directly address intratumor heterogeneity, future research incorporating multiregional sampling and imaging, alongside integrated analyses of genetic heterogeneity, tumor evolution, and molecular subtyping, has the potential to refine our understanding of this complexity.

The ECMS and its derived image-based classifier imECMS, hold significant promise for advancing precision oncology in ESCC, particularly as solutions to current limitations are addressed. Clinically, the ECMS taxonomy can stratify patients for subtype-specific therapeutic trials. For instance, ECMS2-CLS patients, with their characteristic cell cycle dysregulation and frequent ERBB2 amplification, represent ideal candidates for CDK or HER2 inhibitor-based regimens. The imECMS system, by enabling low-cost, rapid subtyping from routine H&E slides, could facilitate the widespread clinical implementation of this strategy, especially in resource-limited settings. Beyond direct therapeutic targeting, future research should focus on several key areas. First, validating these systems in larger, prospective cohorts will be crucial to confirm their predictive power for subtype-specific therapies across all four ECMS categories (e.g., targeted therapies for ECMS1-MET and ECMS2-CLS, immunotherapy for ECMS3-IM, and anti-angiogenic agents for ECMS4-MES). Second, the biological mechanisms underpinning subtype-specific vulnerabilities, such as metabolic reprogramming in ECMS1-MET or immune exclusion in ECMS4-MES, require deeper functional investigation to identify novel drug targets. Finally, integrating imECMS predictions with other readily available clinical data, such as CT imaging features (radiomics) and serum biomarkers, could create a more robust and multifaceted diagnostic and prognostic panel, significantly enhancing its utility in routine clinical decision-making.

In conclusion, this study introduces a consensus molecular classification system, the ECMS, for ESCC to address limitations in existing subtyping methods. The distinct molecular features of each ECMS subtype reveal molecular vulnerabilities for tailoring therapeutic strategies to individual subtypes. Additionally, we developed an image-based classifier that correlates with molecular subtypes, facilitating clinical translation. These findings provide a framework for precision medicine in ESCC and highlight the translational potential of subtype-specific treatment approaches.

Methods

Patient cohorts and data collection

A total of 152 patients (SXM-I), 326 patients (SXM-II), and 32 patients (SXM-III) were recruited from clinical centers in Shanxi Province. Informed consent was acquired from all participants, and ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Boards of both Shanxi Medical University and Shanxi Cancer Hospital. For every enrolled case, a tumor sample was collected alongside a matched adjacent normal tissue control. All tumor entities were classified in accordance with the World Health Organization guidelines. To ensure diagnostic accuracy, the H&E-stained sections from each sample were examined independently by a minimum of three pathologists, who verified that the tumor morphology was consistent with that of ESCC and that the matched normal tissues were free of malignant cells. Clinical staging was performed via the Eighth Edition TNM classification system established by the Union for International Cancer Control and the American Joint Committee on Cancer. The detailed clinical characteristics of the included cohorts are presented in Supplementary Data 1.

The SXM-I cohort (n = 152) included WGS, RNA-seq, small RNA-seq, and WGBS data for paired tumor and adjacent normal samples. The SXM-II cohort (n = 326) included WGS data for tumor and adjacent normal samples. These data were generated from our previous study.9,18 FFPE sections were obtained from Shanxi Cancer Hospital, H&E stained and scanned via an Aperio Scanscope CS and panoramic lens (10× eyepiece and 20× objective). The resulting H&E images from the SXM-I (n = 152) and SXM-II (n = 326) cohorts were used for tissue classification, SOF quantification, and imECMS classification. Additionally, 27 patients in the SXM-II cohort were excluded because of missing follow-up data.

To establish the SXM-III cohort, ESCC patients without preoperative treatment were prospectively recruited, and tumor tissues were collected after curative surgery. For each patient, we employed imECMS for image-based classification on H&E-stained histological images derived from resected tumor tissue. Based on the classification results, we selected eight representative patients for each imECMS-predicted subtype (32 in total) for RNA sequencing. Finally, we performed ECMS subtyping using our gene expression-based classifier as the gold standard to validate the image-based subtyping results.

DNA extraction and whole-genome sequencing

Total DNA was isolated from formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) samples via the Maxwell 16 Tissue DNA Purification Kit (Promega) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol. The obtained high-quality DNA (OD260/280 = 1.8 ~ 2.0) was then sheared to an average size of approximately 350 bp via a Covaris S220 sonicator. The fragmented DNA was subsequently purified with Illumina Sample Purification Beads. The sequencing libraries were constructed via the TruSeq Nano DNA Sample Prep Kit (Illumina), followed by 2 × 150 bp paired-end sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq platform.

RNA sequencing

Total RNA was isolated from frozen samples via TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies) and subsequently treated with DNase I to remove genomic DNA (gDNA) contamination. The integrity and concentration of the purified RNA were assessed via a NanoDrop Spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, USA) and verified via 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. Following quality control, the mRNA was enriched with oligo(dT) beads and fragmented for cDNA library construction. The final cDNA libraries were quality controlled on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer and an ABI StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System prior to sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform for paired-end reads.

WGBS library preparation and sequencing

We extracted gDNA from tissue samples and quantified it via a Qubit fluorometer. Two hundred nanograms of gDNA spiked with 1% unmethylated lambda DNA were randomly fragmented to a 300 bp insert size via sonication with a Covaris LE220, followed by end repair and adenylation. Methylated adapters were subsequently ligated to the fragmented DNA. Bisulfite treatment was performed according to the EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) instruction manual. After PCR amplification (KAPA HiFi HotStart Uracil + ReadyMix (2×)) and purification, we quantified the libraries (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and assessed their size distribution (Agilent BioAnalyzer). Finally, paired-end sequencing (2 × 150 bp) was performed on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 at Mingma Technologies Co., Ltd.

Small RNA library preparation and sequencing

We outsourced RNA purification, reverse transcription, library construction, and sequencing to Mingma Technologies, following Illumina’s protocols. Using the Illumina TruSeq Small RNA Library Prep Kit, we prepared small RNA sequencing libraries from ~1 µg of total RNA. After the 3′ and 5′ adapters were ligated, first-strand and second-strand cDNA synthesis was performed. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with these adapter-ligated fragments as templates with reverse transcriptase and specific RT primers, followed by second-strand cDNA synthesis. Illumina sequencing primers containing indexes were used to amplify the adapter-ligated cDNA via PCR to generate cDNA libraries. Gel purification was used to select 145–160 bp fragments, and a library was constructed. After library construction, the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to quantify the concentrations of the resulting sequencing libraries, and the size distribution was analyzed on an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent). Cluster formation of the libraries was performed on an Illumina cBOT cluster generation system with the HiSeq PE Cluster Kit (Illumina). Paired-end sequencing was performed via an Illumina HiSeq system following Illumina-provided protocols for sequencing at Mingma Technologies.

Sequencing data processing

For the raw sequencing reads, quality control, adapter sequence trimming, low-quality read filtering, and per-read quality pruning were performed via fastp.76 WGS reads were aligned to the hg38 human reference genome assembly with BWA.77 The Sambamba78 tool (0.7.1) was used to convert the SAM file to a BAM file, which was sorted by coordinate. The Picard tool (MarkDuplicates, 2.23.2) was used to mark duplicated reads. The base quality score was recalibrated on the basis of a set of known variants to minimize systematic errors made by the sequencing machine via the GATK tool (4.1.7).79 A panel of normal files was created by combining variants from normal samples. Short variants (somatic mutations and indels) were called by Mutect2 in tumor-normal mode. The raw output of Mutect2 was further filtered based on sequence context artifacts and contamination fractions. Somatic mutations were annotated by ANNOVAR.80 Mutations located in nongene regions or with ExAC_EAS frequency >0.05 or synonymous mutations were excluded from the following analysis. Somatic CNVs were detected via cnv_facets (0.16.0) in tumor samples compared with paired normal samples. The R package “mafTools” was used to analyze both the mutation and SCNV profiles. We also used GISTIC81 to identify genomic regions that were frequently amplified or deleted. The RAN sequencing reads were aligned to hg38 via the STAR aligner (1.5.2).82 Gene expression levels were estimated via RSEM83 according to Ensembl (release 98) reference annotation via uniquely aligned reads. The clean reads from WGBS were aligned via Bismark (0.22.3) with Bowtie2.84 The duplicated reads in the Bismark alignment BAM were removed. A Bismark methylation extractor was used to extract the methylation calls. The small RNA sequencing reads were aligned to miRbase (v21), and miRNA expression profiles were estimated via the miRDeep2 pipeline85 with a minimum alignment length of 17 bp.

ESCC subtyping platforms

Du et al.25 identified three clusters (CNV1–3) via hierarchical clustering on copy number alteration (CNA) of cancer gene census (CGC) genes. The CNV3 group presented the highest frequency of CNAs, whereas the CNV2 group presented the lowest frequency. To obtain cluster labels for patients in the SXM-I cohort, we performed hierarchical clustering on CGC genes whose CNAs were detected by cnv_facets (0.16.0). The hierarchical tree was cut to produce three subgroups. As expected, we found a similar CNA pattern to that reported in Du’s study and assigned cluster labels on the basis of CNA frequencies.

Cui et al.18 revealed three major subtypes (NMF1–3) on the basis of the analysis of WGS data for 508 ESCC patients via a modified nonnegative matrix factorization (NMF) algorithm. The mutation data and subtype labels used in this study were provided by the authors. VRange objects were constructed via the VariantAnnotation package.86 The mutation contexts of 96 trinucleotides were obtained via the SomaticSignatures package.87 A random forest classifier was trained on the mutation context and was employed to predict the subtype labels for patients in the SXM-I cohort.

Liu et al.24: In this study, three subtypes (CU1–3) were identified via consensus clustering analysis on the basis of RNA-seq data. Gene expression values were quantitated as transcript per million (TPM) values. The expression levels of 81 signature genes and patient subtype labels (n = 125) were collected, followed by log2 transformation and scaling by standardized scores. A random forest classifier was subsequently trained and used to predict subtype labels for patients in the SXM-I cohort.

Wang et al.23: In this study, two subtypes (Subtypes 1 and 2) were identified on the basis of a discovery cohort of 179 ESCC patients whose gene expression profiles were derived from the Agilent microarray platform.23,88 The dataset was downloaded from the GEO database (accession code: GSE53625). Microarray probe sequences were aligned to gene sequences (GRCh38, Ensembl annotation) via BLASTN (2.10.0), and probes perfectly matched to a transcript were retained. An expression matrix was prepared and z-normalized. To train a robust classifier, we selected representative patient samples with positive silhouette widths and the top 500 genes with the highest median absolute deviations (MADs) via the random forest algorithm. The classifier was subsequently used to predict subtype labels for patients in the SXM-I cohort.

In this study, Xiong et al.22 identified four subtypes (OncoTarget1-4) via consensus clustering on the GSE38129 (n = 20) and GSE45670 (n = 38) datasets. Both datasets were generated via Affymetrix expression arrays. The datasets were downloaded from the GEO database. Median expression values were calculated if multiple probes were mapped to the same gene. The gene expression data were scaled separately and then merged into a single expression matrix. The samples and signature genes described in the study were used to train a random forest classifier.

TCGA-ESCC45: TCGA reported three subtypes (TCGA1-3) by integrative clustering of multiomics ESCC data via iCluster.89 Since the C3 subtype is a rare subtype with only four cases, we focused on the TCGA1 and TCGA2 subtypes in our analysis. We downloaded the TCGA-ESCC dataset and patient information via the TCGAbiolinks package. Cases of ESCC (n = 78) with multiomics data were selected for further analysis. Gene expression levels were normalized to TPM, log2 transformed, and scaled. A random forest classifier was constructed using the expression levels of genes with the top MADs to predict subtype labels in the SXM-I cohort.

COCA9: This study revealed four subtypes via integrated clustering of clusters derived from different types of single-omics data from the SXM-I cohort. Labels of SXM-I (n = 152) were collected directly from the paper for consensus molecular subtype analysis.

MESCC: We performed subtype identification on the basis of multiomics profiles via SNF.44 More specifically, segment log ratio values were extracted from the cnv_facets result, and the copy number regions were reduced to 2291 regions via the R package “iClusterPlus.” The R package “methylKit” was used to combine the methylation calls of all samples from the CpG context. For each gene, the promoter methylation level (2 kb upstream and 0.5 kb downstream of the transcription start site on the basis of Ensembl annotation) was calculated as the ratio of methylated cytosine to total coverage at all CpG sites in the promoter region. Promoters with ≥20% missing data and low coverage were further filtered out. The gene expression profiles and miRNA expression profiles were normalized to the TPM and reads per million values, respectively, for the following analysis. The top 1000 genes, 500 miRNAs, and 1000 promoter regions with the highest MADs across all samples were selected as the most representative biological features for subtyping. Before the similarity graph was constructed, each type of omics data was z-normalized, and the pairwise distances between samples were calculated via the Euclidean distance. The R package “SNF”44 was used to construct the similarity graph and the fused network with hyperparameters of alpha = 0.75, K = 30, and T = 20. A spectral clustering algorithm was used to obtain cluster labels for each patient.

Identification of consensus molecular subtypes and subtype associations

To systematically investigate the associations between the eight ESCC subtyping systems, we employed a network-based approach established previously for the identification of the consensus molecular subgroups of colorectal cancer.48 To this end, we evaluated the statistical associations between the total 25 subtypes via the classification labels derived from the eight subtyping systems for all the samples in the SXM-I cohort. More specifically, we first randomly subsampled 85% of the total samples from the SXM-I cohort and performed hypergeometric tests for overrepresentation of patient samples classified into one subtype in another. A network of 25 nodes (subtypes) was constructed, with edges encoding significant associations (P < 0.05, hypergeometric tests). This network was subsequently partitioned into clusters via the Markov cluster algorithm (MCL),90 with the inflation factor set to 1.7. The analysis was repeated 100 times to ensure clustering stability. Aggregating all the clustering results, we constructed a 25 × 25 consensus matrix, which represented the frequency with which each pair of subtypes was partitioned into the same cluster. Finally, using MCL on the consensus matrix, we identified four consensus molecular subtypes of ESCC (ECMS).

Identification of core consensus samples

For each ESCC sample in the SXM-I cohort, we performed a hypergeometric test for the overrepresentation of assigned subtypes in the set of subtypes associated with each ECMS. The ESCC sample is assigned to an ECMS if the corresponding overrepresentation test has an FDR < 0.2 and is considered a core consensus sample. Consequently, 75.6% of all the samples were identified to be highly representative of that particular consensus subtype. These core consensus samples were used to predict the ECMS labels of nonconsensus samples via a random forest algorithm.

Construction of an ECMS classifier

A random forest classifier was built to facilitate the application of the ECMS to other gene expression datasets. For each subtype, differential expression analysis was performed via comparisons with the other three subtypes. Genes with an AUC > 0.8 and Benjamini‒Hochberg (or BH)-adjusted P < 0.05 were selected as signature genes. Since there are 69 samples with ECMS2-CLS but only 24 samples with ECMS4-MES, a balanced classification model was constructed by setting the “sampsize” argument to 24 in the randomForest package, ensuring equal-sized stratified sampling of each ECMS when constructing each decision tree.

Identification of subtype-specific multiomics signatures

We performed differential analysis between each subtype and the other subtypes via the R package “LIMMA.”91 The mRNA signature was identified by differentially expressed genes (BH-adjusted P < 0.05 and |logFC| > 1) for each subtype (Supplementary Data 6). The DNA methylation signature was identified by differentially methylated gene promoters (BH-adjusted P < 0.05 and absolute delta beta value > 0.1) for each subtype (Supplementary Data 7). The miRNA signature was identified by differentially expressed miRNAs (BH-adjusted P < 0.05 and |logFC| > 0.5) for each subtype (Supplementary Data 8).

Gene set enrichment analysis

Genes were ranked by log2-fold change. GSEA was performed via the R package “HTSanalyzeR2” with 10,000 permutations.92 We focused on previously described signatures of pathway activity, cancer hallmarks, and well-characterized cellular processes. Up- and downregulated gene sets were identified (BH-adjusted P < 0.05). The p values derived from GSEA were log10-transformed.

Immune cell infiltration analysis

RNA-seq data were used to estimate the immune cell content within a sample via the TIMER in the R package “deconvolution.” TIMER was used to robustly estimate the infiltration levels of six types of immune cells: B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells. In addition, immune scores and stromal scores were calculated for each sample via deconvolution of gene expression profiles via ESTIMATE.61

Drug sensitivity analysis

The chemotherapy drug response was predicted via the OncoPredict package on the basis of gene expression.93 Cell line drug sensitivity data from the Cancer Therapeutics Response Portal94 (CTRPv2, https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ctrp.v2/) were selected as the training dataset. Low-variability genes were removed before applying the calcPhenotype function to predict drug sensitivity. Potential drug-targeting genes were obtained from Simplicity.95 We further performed differential analysis to investigate subtype-specific expression profiles. We also subset the data for 23 esophageal cancer cell lines from the CTRPv2 dataset and performed correlation analysis between drug sensitivity and target gene expression.

H&E image collection and preprocessing

To develop a model for ESCC tissue classification, we manually annotated contiguous pure tissue areas and extracted nonoverlapping image patches of size 256 × 256 pixels (px) at a magnification of 20×. The image patches were categorized into eight classes: background (BACK), connective tissue (CON), squamous epithelium (EPI), gland (GLA), lymphocyte (LYM), smooth muscle (MUS), cancer-associated stroma (STR), and tumor (TUM). An experienced pathologist manually annotated 60 H&E-stained slides of ESCC tissue in the SXM-I cohort following the same criteria as described previously, without clinical follow-up data.96 Manually annotated tissue regions were divided into nonoverlapping patches, yielding a training set of 48,376 patches from 40 H&E slides and a testing set of 3996 patches from 20 slides (Supplementary Data 10).

H&E-stained slides containing >50% glands/squamous epithelium area or <10% tumor regions were considered poor quality and excluded. Pathologists’ review was performed to further select high-quality and relevant images for the following analysis. All WSIs were partitioned into nonoverlapping 256 × 256 pixel (px) tiles at 20× magnification via Openslide (https://openslide.org/), followed by color normalization.97 Tiles with a high ratio of blank surface (>50%) were removed.

Deep learning-based tissue classification

For ESCC tissue classification, we trained a deep convolutional neural network (CNN) based on the ResNet50 model98 to classify the eight tissue types (Fig. 4a). To initialize the training of the ESCC tissue classifier, we employed transfer learning of the established colorectal cancer tissue classification network from our previous work.70 Among all the tissue patches in the dataset (n = 48,376), 70% were randomly selected, followed by image augmentation for the training of the model and 30% for validation. To prevent overfitting, we fixed the parameters of the top 3 child blocks. The ResNet50 model was trained with a learning rate of 2 × 10−7 and a batch size of 64 using the RMSprop optimizer. Categorical cross-entropy loss was used for model optimization. The trained ESCC tissue classifier was evaluated in the independent testing dataset (n = 3996) and subsequently applied to classify all the preprocessed image patches in the SXM cohort. The deep learning-based tissue classification analysis was performed via Python (v.3.8) via the PyTorch library (v.1.5).

Calculation of multiscale spatial organization features

Following tissue classification, multiple types of SOFs proposed by other groups and us were quantified to systematically dissect the ESCC TME (Fig. 5a):

-

1.

First-order features represent the distributions of various types of tissues.

-

Overall, SOFs were calculated by the relative proportions of image patches classified to each tissue type (e.g., tumor, stroma, lymphocyte, mucus) within the tumor, tumor-proximal, and tumor-distal regions, as well as the whole-slide image. More specifically, we classified the tissue patches of lymphocytes (LYMs) and stroma (STRs) on the basis of Gaussian mixture modeling. Tumor-proximal and tumor-distal SOFs were subsequently quantified by the ratios of tissue patches classified to the corresponding classes to the total number of tissue patches in the WSI.

-

The within-tissue dispersion index (WCDI),99 a measure of regional dispersion within a certain range of neighborhoods, is defined as:

$$WCD{I}_{A}=\frac{1}{{n}_{A}}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i\in A}\frac{1}{{n}_{{A}_{i}}}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{j\in {A}_{i}}d\left(i,j\right)$$(1)where A represents a set of patches of a specific tissue type and where \({d}\left(i,j\right)\) denotes the Euclidean distance between patches i and j, which is within the neighborhood of i.

-

-

2.

Second-order features representing interactions between various types of tissues (e.g., tumor-stroma, tumor-lymphocyte interactions):

-

Pairwise tissue interactions between tumor and nontumor tissues were calculated in regions of interest (ROIs, described below) for each tumor patch. The interactions were defined as the relative proportions of nontumor tissue patches assigned to different tissue types in each ROI.

-

The between-cluster dispersion index (BCDI),99 a measure of the overall distance between two different types of tissues, is defined as:

$$BCD{I}_{A,B}=\frac{{\sum }_{i\in A,\,j\in B,A\ne B}d\left(i,j\right)}{{n}_{A}{n}_{B}}$$(2)where A and B represent two different types of tissues; nA and nB are the numbers of patches for the two tissues; and d(i, j) denotes the Euclidean distance calculated on the basis of the coordinates of patches of the ith patch of tissue A and jth patch of tissue B.

-

-

3.

Higher-order features quantifying the regional/global diversity:

-

The spatial diversity index (SDI)100 is an ecological statistic used to quantify the degree of spatial heterogeneity of various cell/tissue types and was calculated for each ROI with only the stroma (STR), lymphocytes (LYM) and tumor (TUM):

$$SDI=-{\sum }_{i=1}^{m}\,{p}_{i}\,ln\,{p}_{i}$$(3)where m is the number of tissue types and where \({p}_{i}\) is the proportion of image patches belonging to the ith tissue type.

-

Kullback–Leibler divergence (KLD)100 quantifies the intercore heterogeneity determined by the difference in the cellular content relative to the patient’s overall distribution of single-cell phenotypes. Intercore heterogeneity within an ROI was approximated by calculating the KLD from the tissue-type distribution (proportions of each tissue type) of an ROI to the average tissue-type distribution across all ROIs from a WSI. The R package entropy (v.1.2.1) was used for the calculation of both the SDI and the KLD.

-

The Morisita‒Horn similarity index (M–H index),101 an ecological measure of community structure and predator‒prey interactions, was used to quantify the extent to which tumors and other types of tissue colocalize in the WSI. Spatial correlation was computed via Pearson correlation and Morisita‒Horn’s similarity index with the number of tumors and other types of tissue in each ROI. Let \({p}_{i}^{o}\) and \({p}_{i}^{t}\) denote the fraction of other types of tissue and tumor in polygon i:

$$M=\frac{2{\sum }_{i}{p}_{i}^{l}{p}_{i}^{c}}{{\sum }_{i}{({p}_{i}^{l})}^{2}+{\sum }_{i}{({p}_{i}^{c})}^{2}}$$(4) -

Texture features,102 including the gray level co-occurrence matrix, gray level run length matrix, and gray level size zone matrix (GLSZM), were calculated via the R package radiomics via the classified WSI matrix.

-

A 2048 × 2048 pixel window was used to scan the tumor regions to obtain ROIs. The ROIs were identified by local tissue regions with at least 25% tumor (TUM) patches and no more than 50% background (BACK) patches. We calculated overall SOFs, WCDI, pairwise tissue interactions, SDI, KLD, and the Morisita‒Horn index for all the ROIs identified and took the average as the overall estimation of the entire tissue slide and patient. For comprehensive and generalized characterization of the TME from H&E-stained slides, we employed ROI-based quantification at different magnifications (5×, 10×, and 20×). In total, 317 SOFs were identified for the following analysis.

Spatial organization feature-based subtyping classification

The SXM-I cohort, which included both H&E slides and multiomics profiles, was used for training and internal validation of the image-based classifier. The SXM-II cohort, which includes only H&E slides and clinical information, was used to validate the associations with clinicopathological characteristics observed in the SXM-I cohort. A total of 152 patients with multiomics subtypes were included in the study. To eliminate the impacts of the magnitude scale, we perform z-score normalization and filter out seven features with low between-sample variations (MAD = 0). Since the subtyping of the SXM-I cohort was obtained from classification via SNF, the mean value of the silhouette for all the patients was used as a measure of how tightly grouped all the data in the cluster were.44 To identify highly representative samples for our multiomics subtype, we select the median value of the silhouette on SXM-I samples as a cutoff. As a result, 37 patients with 161 H&E slides were discarded, and 115 patients with 465 H&E slides were retained for downstream analysis. Considering the potential heterogeneity between multiple histological slides within each individual tumor, we set the molecular subtype label for each slide from the overall multiomics subtyping call of the corresponding tumor sample and then performed a random sampling method to identify outliers. More specifically, we constructed an extremely randomized tree classifier on 80% of the randomly selected slides and obtained predictions on the other 20% of the slides with 100 repeats. Slides misclassified more than 90% of the time were excluded as outliers. After 179 slides were excluded, we used 10-fold cross-validation with 100 repeats on the retained samples (102 patients with 286 H&E slides) to assess the performance of the prediction models. Then, we trained a subtyping classifier (imECMS) on all 286 H&E slides via extremely randomized trees and evaluated the general applicability of the classifier to another independent cohort (SXM-II). An overall imECMS prediction for each patient with multiple slides was determined as the category corresponding to the most frequently appearing ECMS subtype among the multiple slides (excluding from the analysis if there was no predominant subtype). Specifically, owing to the significant impact of ECMS4-MES on the prognosis observed, any patient with the presence of ECMS4-MES in multiple slides was classified into the ECMS4-MES subtype. We further identified the specific highly expressed SOFs for particular subtypes via one-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank tests by comparing each subtype with the others in terms of the values of the SOFs.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed via R (version 4.0.0). Follow-up medians and their interquartile ranges (IQRs) were derived via the Kaplan–Meier estimator. Categorical variables are summarized as counts and percentages, whereas continuous variables are described as medians and IQRs. Group differences in continuous measurements were assessed via the Wilcoxon signed-rank test from the R “stats” package. Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate associations between pairs of SOFs and between SOFs and continuous clinical features. Survival differences in OS prediction were examined via log-rank tests implemented in the R “survival” package. The predictive performance of subtyping was assessed through receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analyses via the “multiROC” package. Patient-level alluvial diagrams for image-based subtype predictions were generated with the “ggalluvial” package.

Data availability

All data related to the present study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive (GSA) in the BIG Data Center (http://bigd.big.ac.cn/gsa), Beijing Institute of Genomics (BIG), Chinese Academy of Sciences: HRA003107 (WGS & RNA-seq of SXM-I, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA003107), HRA003533 (WGBS of SXM-I, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA003533), and HRA012764 (RNA-seq of SXM-III, https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/browse/HRA012764). Proteomic data were uploaded to the Open Archive for Miscellaneous Data (OMIX), China National Center for Bioinformation/Beijing Institute of Genomics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/omix): OMIX006723 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/omix/preview/GQXX0rcV). TCGA-ESCC transcriptomic data are accessible from the TCGA Esophageal Cancer cohort20: GSE45679: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE45670. GSE53625: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE53625.

Code availability

The code for comprehensive analysis, as described in the present study, and figure generation, as shown, can be found at https://github.com/CityUHK-CompBio/ESCC_CMS.

References

Chu, C. E. et al. Heterogeneity in NECTIN4 expression across molecular subtypes of urothelial cancer mediates sensitivity to enfortumab vedotin. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 5123–5130 (2021).

Lin, L. & Lin, D. C. Biological significance of tumor heterogeneity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancers 11, 1156 (2019).

Huang, A. et al. Novel hypoxia- and lactate metabolism-related molecular subtyping and prognostic signature for colorectal cancer. J. Transl. Med. 22, 587 (2024).

Zhao, L., Lee, V. H. F., Ng, M. K., Yan, H. & Bijlsma, M. F. Molecular subtyping of cancer: current status and moving toward clinical applications. Brief. Bioinform. 20, 572–584 (2019).

Qin, W. et al. Multiomics-based molecular subtyping based on the commensal microbiome predicts molecular characteristics and the therapeutic response in breast cancer. Mol. Cancer 23, 99 (2024).

Liu, Q. et al. Proteogenomic characterization of small cell lung cancer identifies biological insights and subtype-specific therapeutic strategies. Cell 187, 184–203 e28 (2024).

Hoadley, K. A. et al. Cell-of-origin patterns dominate the molecular classification of 10,000 tumors from 33 types of cancer. Cell 173, 291–304 e6 (2018).

Chakraborty, S., Sharma, G., Karmakar, S. & Banerjee, S. Multi-OMICS approaches in cancer biology: new era in cancer therapy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 1870, 167120 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. Integrated multi-omics profiling yields a clinically relevant molecular classification for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cancer Cell 41, 181–195.e9 (2023).

Lindskrog, S. V. et al. An integrated multi-omics analysis identifies prognostic molecular subtypes of non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Nat. Commun. 12, 2301 (2021).

Migliozzi, S. et al. Integrative multi-omics networks identify PKCdelta and DNA-PK as master kinases of glioblastoma subtypes and guide targeted cancer therapy. Nat. Cancer 4, 181–202 (2023).

Wang, Y., Zhang, L., Yang, Y., Lu, S. & Chen, H. Progress of gastric cancer surgery in the era of precision medicine. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 17, 1041–1049 (2021).

Law, H. C. et al. The proteomic landscape of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma liver metastases identifies molecular subtypes and associations with clinical response. Clin. Cancer Res. 26, 1065–1076 (2020).

Kamoun, A. et al. A consensus molecular classification of muscle-invasive bladder cancer. Eur. Urol. 77, 420–433 (2020).

Joanito, I. et al. Single-cell and bulk transcriptome sequencing identifies two epithelial tumor cell states and refines the consensus molecular classification of colorectal cancer. Nat. Genet. 54, 963–975 (2022).

Ten Hoorn, S., de Back, T. R., Sommeijer, D. W. & Vermeulen, L. Clinical value of consensus molecular subtypes in colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 114, 503–516 (2022).

Yan, T. et al. Multi-region sequencing unveils novel actionable targets and spatial heterogeneity in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 10, 1670 (2019).

Cui, Y. et al. Whole-genome sequencing of 508 patients identifies key molecular features associated with poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Cell Res. 30, 902–913 (2020).

Dagogo-Jack, I. & Shaw, A. T. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 15, 81–94 (2018).

Cancer Genome Atlas Research, N. etwork et al. Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature 541, 169–175 (2017).

Chen, R. et al. Patterns and trends in esophageal cancer incidence and mortality in China: An analysis based on cancer registry data. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 3, 21–27 (2023).

Xiong, T. et al. An esophageal squamous cell carcinoma classification system that reveals potential targets for therapy. Oncotarget 8, 49851–49860 (2017).

Wang, F. et al. Gene expression profiling reveals distinct molecular subtypes of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in Asian populations. Neoplasia 21, 571–581 (2019).

Liu, M. et al. Molecular analysis of Chinese oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma identifies novel subtypes associated with distinct clinical outcomes. EBioMedicine 57, 102831 (2020).

Du, P. et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma reveals clinical relevance. Sci. Rep. 7, 15324 (2017).

Matsutani, S. et al. Tumor-infiltrating immune cells in H&E-stained sections of colorectal cancer tissue as a reasonable immunological biomarker. Anticancer Res. 38, 6721–6727 (2018).

Jakubowska, K., Kisielewski, W., Kańczuga-Koda, L., Koda, M. & Famulski, W. Diagnostic value of inflammatory cell infiltrates, tumor stroma percentage and disease-free survival in patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol. Lett. 14, 3869–3877 (2017).

Tsai, P.-C. et al. Histopathology images predict multi-omics aberrations and prognoses in colorectal cancer patients. Nat. Commun. 14, 2102 (2023).

Jiang, B. et al. Deep learning applications in breast cancer histopathological imaging: diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis. Breast Cancer Res. 26, 137 (2024).

Wang, K. S. et al. Accurate diagnosis of colorectal cancer based on histopathology images using artificial intelligence. BMC Med. 19, 76 (2021).

Bouzid, K. et al. Enabling large-scale screening of Barrett’s esophagus using weakly supervised deep learning in histopathology. Nat. Commun. 15, 2026 (2024).

Alam, M. et al. Abstract 6329: Using low-resolution, low-cost histopathology images to predict esophageal squamous cell carcinoma via deep learning. Cancer Res. 82, 6329–6329 (2022).

Skrede, O.-J. et al. Deep learning for prediction of colorectal cancer outcome: a discovery and validation study. Lancet 395, 350–360 (2020).

Wei, T. et al. Survival prediction of stomach cancer using expression data and deep learning models with histopathological images. Cancer Sci. 114, 690–701 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Deep learning analysis of histopathological images predicts immunotherapy prognosis and reveals tumour microenvironment features in non-small cell lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer 131, 1833–1845 (2024).

Ahn, B. et al. Histopathologic image-based deep learning classifier for predicting platinum-based treatment responses in high-grade serous ovarian cancer. Nat. Commun. 15, 4253 (2024).

Coudray, N. et al. Classification and mutation prediction from non-small cell lung cancer histopathology images using deep learning. Nat. Med. 24, 1559–1567 (2018).

Yan, R. et al. Histopathological bladder cancer gene mutation prediction with hierarchical deep multiple-instance learning. Med. Image Anal. 87, 102824 (2023).

Bilal, M. et al. Development and validation of a weakly supervised deep learning framework to predict the status of molecular pathways and key mutations in colorectal cancer from routine histology images: a retrospective study. Lancet Digit. Health 3, e763–e772 (2021).