Abstract

Background

Recent evidence indicates that the risk of death by suicide in teenagers has increased significantly worldwide. Consequently, different therapeutic interventions have been proposed for suicidal behavior in this particular population. Therefore, the main objective of this study is to provide an updated review of the existing psychological interventions for the treatment of suicide attempts (SA) in adolescents and to analyze the efficacy of such interventions.

Methods

A systematic review was conducted following PRISMA guidelines. The studies were identified by searching PubMed, PsychINFO, Web of Science, and Scopus databases from 2016 to 2022. According to the inclusion criteria, a total of 40 studies that tested the efficacy of different psychological interventions were selected.

Results

Various psychological interventions for adolescents with suicidal behaviors were identified. Most of those present promising results. However, to summarize results from recent years, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) was the most common and the only treatment shown to be effective for adolescents at high risk of suicide and SA. In contrast, empirical evidence for other psychological interventions focusing on deliberate self-harm (SH) is inconclusive.

Conclusions

Interventions specifically designed to reduce suicidal risk in adolescents have multiplied significantly in recent years. There are a few promising interventions for reducing suicidal behaviors in adolescents evaluated by independent research groups. However, replication and dismantling studies are needed to identify the effects of these interventions and their specific components. An important future challenge is to develop brief and effective interventions to reduce the risk of death by suicide among the adolescent population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suicide is one of the leading causes of death among 10–19-year-olds and is a major public health concern [1, 2]. Despite increasing interest in this problem, the number of adolescent deaths from suicide has risen more than 50% in the past decade [3]. Among all risk factors, suicide attempts (SA) have been identified as the most robust precursor in people who die by suicide [4]. Suicidal ideation (SI) and self-harm (SH), including non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), have also been considered risk factors for SA as well as potent predictors for eventual death [5].

Over the past two decades, psychotherapies specifically designed to reduce suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adolescents have multiplied significantly [6, 7]. Although different psychological interventions have been proposed, there is no consensus, nor is there enough empirical evidence to support the use of these psychological treatments in clinical practice. Furthermore, reviews on the topic sometimes include old-fashioned psychotherapies, whose efficacy has not been replicated in new studies. In addition, they include overly wide age ranges and do not even differentiate between young adults and adolescents, so they do not focus on that particular developmental stage. There are few studies focusing on the efficacy of interventions to reduce SA compared with research targeting NSSI or a broad definition of SH (including NSSI and SA) [8]. Therefore, the main aim of this systematic literature review is to identify interventions targeting SA. The second aim is to provide a comprehensive, updated, and critical overview of the efficacy of psychological interventions for adolescents with suicide-related behaviors.

Material and methods

This review was entered into the international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews with a health-related outcome (PROSPERO 2022 CRD42022308981). It follows the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [9] (Supplementary Table 1).

Search strategy

Searches were conducted in four electronic databases (PUBMED, PsycINFO, Web of Science, and Scopus), from 1 January 2016 to 31 December 2022, to identify updated research evaluating the efficacy of psychological interventions for adolescents with suicidal behaviors and specifically SA.

The following keywords were used to form the basis of the search strategy. First, terms referring to suicidal behavior (“suicide”, “suicidal behavior”, “suicidal behavior”, “SH,” “SA”); second, terms specifying the age group (“adolescent”, “teenager”, “adolescence”, “teenage”, “youth”, “young”); and finally, interventions (“psychological treatment”, “psychological intervention”, “psychotherapy”, “psychological therapy”, “therapy”, “psychotherapeutic”).

We supplemented the database search by reviewing reference lists of articles meeting our inclusion criteria (backward reference search).

Study selection

Inclusion criteria were: (a) adolescents with recent suicidal behavior, (b) aged 10–19 years old, (c) studies of psychological interventions for the treatment of suicidal behavior, (d) measuring a specific self-injurious behavior outcome, including primary or secondary SA, and (e) published in English or Spanish.

Exclusion criteria were: (a) case studies, clinical descriptions, qualitative studies, reviews, and meta-analyses, (b) book chapters, editorials, or theses; (c) studies that did not aim to reduce suicide-related behavior and/or whose participants were not recruited based on the presence of suicidal behavior, or (d) studies that exclusively measured NSSI or SI.

In the first instance, study titles and abstracts were screened by two researchers (AGF and MTBB). They then screened full texts of potentially relevant studies to determine their inclusion in the database. In the event of unclear information, each case was discussed with another researcher (PAS).

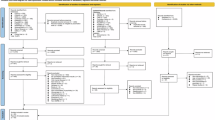

The initial search of these four databases identified 2808 articles (see Fig. 1 for full flowchart). After removing duplicates, the database search returned a total of 1860 articles. Following the initial screening of all record titles and abstracts, 84 full-text articles were identified, of which 51 were excluded for various reasons: 29 not related to topic, 16 incorrect age range, 2 no results presented, and 4 reviews. Based on reading the full texts, 33 articles were selected.

An additional 16 articles were identified from other sources. Some are cited in one or more of the included studies and others were identified from reference list searches of previous systematic reviews. Of these, two reports were excluded because they were not related to the topic, one review, one incorrect age range, four qualitative studies, and one editorial. Thus, 7 studies met the inclusion criteria.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data were extracted from the studies by one researcher (AGF) using a pilot-tested pro forma. The following information was collected from each manuscript: (1) Report: authors and year of publication; (2) Design; (3) Description of the sample (size, age, sex); (4) Characteristics of the interventions: type of intervention and psychological approach, setting (in/outpatient) and duration of intervention; (5) Outcome measures and type of suicidal behavior assessed; (7) Pharmacotherapy; (8) Main results (p value); (9) Reports were categorized for their level of evidence according to the Oxford criteria [10].

The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by two researchers (AGF & MTTB) using the modified Jadad scale [11]. This scale comprises eight items: randomization, blinding, withdrawals, dropouts, inclusion/exclusion criteria, adverse effects, and statistical analysis (Supplementary Table 2). Each article received a total score ranging from 0 to 8, calculated by summing the scores of each item. Studies scoring between 0 and 3 were considered low quality, while those scoring between 4 and 8 were deemed high quality (Supplementary Table 3).

Results

A total of 40 articles met the inclusion criteria for this systematic review:

-

Eleven articles tested the efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy (DBT).

-

Six articles tested the efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT).

-

Five articles tested the efficacy of psychodynamic therapy.

-

Six articles tested the efficacy of family therapy (FT).

-

One article tested the efficacy of support-based therapy.

-

Four articles tested the efficacy of brief skills training.

-

Three articles tested the efficacy of motivational interviewing-based intervention.

-

Two articles tested the efficacy of intensive community care service.

-

One article tested the efficacy of integrative therapies.

-

One article tested the efficacy of combination therapies.

We created four tables (Table 1a–d) to summarize information for each study, providing detailed and transparent data. Supplementary Table 4 was created to provide a more detailed description of the different psychological interventions.

Dialectical behavior therapy

DBT has been one of the most widely used interventions for adolescents with self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. Until 2015, no randomized clinical trial (RCT) had examined the efficacy of DBT in adolescents, and no study had demonstrated the superiority of DBT over a control treatment [6]. Since then, this intervention has been proposed in a wide variety of studies for the treatment of SH, but only recently have the first trials supporting its efficacy emerged (Table 1a).

The first longitudinal research that tested the efficacy of DBT with promising results was carried out by Mehlum et al. in [12]. The authors found that DBT-Adolescents (19 weeks) is more effective than enhanced treatment as usual (E-TAU) in reducing SH (NSSI and SA combined) (Δ slope = −0.92, p = 0.021) and SI (Δ slope = −0.62, p = 0.010) in adolescents with features of borderline personality disorder (BPD). Subsequent 1-year and 3-year follow-ups showed that DBT-adolescents was superior to E-TAU in reducing SH episodes (Δ slope = −9.4, p < 0.05; E-TAU vs DBT interquartile range, IQR = 18.00 vs 7.00, p < 0.001, respectively) with no significant differences for SI [13, 14].

Another multisite trial assessing the effectiveness of DBT compared with individual and group supportive therapy (IGST) [15] differentiated SA from overall SH (6 months with weekly individual and multi-family group sessions). IGST offers a manualized intervention to address the limitations of the control intervention in the Mehlum study. Results demonstrated significant advantages of DBT-Adolescents in all primary outcome measures post-treatment (SA: odds ratio (OR) = 0.30; confidence interval (CI) 95% = 0.10, 0.91, p < 0.05), (NSSI: OR = 0.32; 95% CI: 0.13, 0.77, p < 0.05), (SH: OR = 0.33; 95% CI:0.14, 0.78, p < 0.05), (SI: t = 2.20, p = 0.03; Cohen’s d = 0.034). However, these between-group differences were not statistically significant at the 12-month follow-up. Another 6-month open-label trial to examine the efficacy of DBT in clinical community settings [16] (weekly individual sessions, weekly family group skills training, telephone counseling, and consultation with professional staff), showed significant pre/post-treatment decreases in SA (Z = −2.00, p = 0.046), NSSI (Z = −3.21, p = 0.001), and SI (t = 5.31, p < 0.001).

Hancock-Johnson et al. [17] performed a retrospective study to test the effectiveness of inpatient DBT skills training that showed statistically significant reductions in total SH (Z = −2.443, p = 0.015) (effect size = 0.37) and specifically in the frequency of head-banging (Z = −2.195, p = 0.028) (effect size = 0.34). However, the treatment had no effect on other self-injurious behaviors.

Flynn et al. [18] examined the pre/post-treatment effectiveness of 16-week DBT-adolescents in community settings. Significant pre/post-treatment improvements on the presence (89 vs 64%, p < 0.001) and frequency (p < 0.001) of SH and SI [mean, SE (95% CI): −4.19, 0.069 (−5.53, −2.84), p < 0.001] were observed and maintained over the 16-week follow-up: SH (presence: 60 vs 35%, p = 0.003; frequency: p = 0.03) and SI [mean, SE (95% CI): −6.28, 0.83 (−7.91, −4.65), p < 0.001]. On the other hand, they compared the effectiveness of 16-week vs 24-week DBT-Adolescents [19], and both groups showed significant improvements in the presence and frequency of SH and SI pre/post-treatment. However, 24-week DBT-Adolescents showed additional benefits in reducing SI [mean (95% CI): −2.46 (−4.65, −0.26), p = 0.03].

Another study [8] implemented an RCT to examine the effectiveness of 16-week DBT-adolescents compared with treatment as usual (TAU) plus group sessions (GS) in adolescents with suicidal risk in community clinical settings. Findings indicated that DBT-Adolescents significantly reduced the frequency of NSSI compared with TAU + GS [baseline-adjusted means 1.3 (0.7–1.9) vs 2.1 (1.5–2.7); p = 0.045; difference (95% CI): −0.8 (−1.7, −0.02); Cohen’s d = 0.73]. Both interventions showed a reduction in the number of SA during the intervention, and no SA were reported at the end of treatment. Both treatments were equally effective on SI, but no statistically significant between-group differences were found.

Tebbett-Mock et al. [20, 21] examined the efficacy of DBT during hospitalization. Firstly [20], the authors conducted a retrospective chart review to compare DBT versus TAU in an acute care psychiatric unit. Gains for DBT were observed across all “behavior incidents” (SA, NSSI, and patient-to-patient or patient-to-staff aggressions). Adolescents in the DBT group reported significantly fewer incidents of SA (U = 78412.5, p = 0.01) and NSSI (U = 77436.5, p < 0.05) during treatment than those receiving TAU. However, no significant differences were found between adolescents receiving DBT and TAU in terms of constant observation hours for suicidal ideation or aggression, seclusions, or readmissions to the unit. They then selected a new cohort of hospitalized adolescents who received DBT (DBT Group-2) over the same period of 8 months the year after the first DBT group (DBT Group-1). Consistent with previous findings, DBT Group-2 was comparable to DBT Group-1 in the number of constant observation hours for self-injury, retrains, and days hospitalized. However, adolescents in DBT Group-2 reported a significantly greater number of SA than adolescents in DBT Group-1 (U = 82662.5, p = 0.037) and were comparable to the TAU group. Further, adolescents in DBT Group-2 had significantly greater episodes of NSSI compared to DBT Group-1 (U = 71724.5, p < 0.001) and TAU (U = 65649.0, p < 0.001). The authors concluded that staff turnover and lack of training may account for the lack of sustainability and efficacy of the intervention.

Finally, Hiller and Hughes [22] evaluated the effectiveness of DBT-adolescents in adolescents with BPD features under routine mental health-care conditions. All teens participated in at least one cycle of the program (19 weeks), with the possibility to continue in consecutive cycles (two and three). Results showed significant reductions in SA and NSSI during both the first treatment cycle (SA: Z = −2.52, p = 0.02) and the total course of treatment (SA: Z = −1.95, p = 0.05; NSSI: β = −0.009, Seβ = 0.004, t-ratio = −2.63, p = 0.009).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy

Six studies examined the efficacy of CBT in reducing suicidal thinking and behaviors in adolescents (Table 1b). Hetrick et al. [23] developed an Internet-based CBT (Reframe-IT) for adolescents at suicide risk. The Reframe-IT program consists of eight CBT modules delivered online over a 10-week intervention period and 22-week follow-up. Greater reductions in SA and SI were reported in the Reframe-IT group compared to the TAU group. However, between-group differences were not statistically significant either post-treatment or at follow-up.

Hogberg and Hällström [24] compared mood regulation-focused CBT (MR-CBT) with TAU over an 8-month period. Results showed that suicidal events (active SI and/or SA) were significantly reduced in the MR-CBT group at the end of treatment (p < 0.01), while this effect was not noticeable in the TAU group (p = 0.2). However, between-group differences were not statistically significant.

Esposito-Smythers et al. [25] conducted research to test whether family-focused outpatient CBT (F-CBT) would be more effective than E-TAU for adolescents with depression hospitalized for SA or SI. Over the course of treatment, both groups reported reductions in SA, SI, and NSSI rates. However, there were no significant between-group differences at 6–12–18 months post-randomization.

A randomized pilot trial was conducted to compare a cognitive-behavioral family-based alcohol, deliberate SH, and HIV prevention program (ASH-P) versus an assessment-only control (AO-C) in adolescents in mental care [26]. Results showed no significant differences in any risk behaviors between the two groups at 6-month follow-up. However, at 12-month follow-up, ASH-P was associated with significantly lower odds of SH (large effect; d = −1.01) (OR = −1.84; 95% CI: −3.63, −0.06; p ≤ 0.05) as well as significant reductions in number of SH (large effect; d = −1.90) (OR = −13.23; 95% CI: −21.67, −4.77; p ≤ 0.01) compared with AO-C. No significant differences were found across interventions in SI at 6–12-month follow-up.

Goldston et al. [27] developed an integrated CBT grounded in the relapse prevention model (CBT-RP) for treating adolescents with co-occurring suicidal behavior, depression, and substance use disorders. In a small pilot RCT among outpatient adolescents, CBT-RP (20 weeks) plus enhanced TAU was compared with enhanced TAU alone. The majority of adolescents in both groups showed reductions in SI from baseline to the end of treatment and at 3-month follow-up. The SA rate also did not differ between the two treatments.

Finally, Duarté-Vélez et al. [28] conducted a 6–14-week randomized pilot trial to compare sociocognitive-behavioral therapy for suicidal behaviors (SCBT-SB) versus TAU in adolescents in community clinics through home-based services. Adolescents in both conditions reported reductions in SI over the course of treatment. There was no between-groups treatment effect on SI at any follow-up assessment point. However, a large effect was found on SA in the SCBT-SB group from the 6 to 12-month follow-ups (Cohen’s h = 0.8).

Psychodynamic therapy

Mentalization-based therapy (MBT)

Based on prior positive results of MBT-Adolescents [29], Griffiths et al. [30] adapted the adult MBT introductory group manual (MBTi) [31] in a 12-week intervention for adolescents (MBT-Ai). Over the course of treatment, self-reported SH and emergency department visits for SH decreased significantly in both MBT-Ai and TAU groups (F = 6.29, p < 0.01; F = 9.55, p < 0.001, respectively), although there were no significant between-group differences.

Beck et al. [32] examined the effectiveness of MTB in groups (MBT-G) (1 year) for adolescents with BPD. Compared with TAU, no significant between-group differences were found in the frequency of SH at the end of 1 year of treatment. Consistent with these findings, Jørgensen et al. [33] found that MBT-G was not more effective than TAU at follow-up after 3 and 12 months. In addition, mean SH values were almost unchanged during treatment and subsequent follow-ups in both groups. Despite no indication of the superiority of either therapy, these RCTs were based on the preliminary findings of Bo et al. [34], who found that MBT-G significantly reduced the frequency of SH from baseline to end of treatment in adolescents with BPD (t = 3.13; p = 0.005) (OR = 7.6; 95% CI: 2.6, 12.6) (Table 1b).

Psychodynamic family-based therapy

Based on prior positive results [35], Diamond et al. [36] conducted a second RCT to compare the efficacy of attachment-based family therapy (ABFT) to family-enhanced nondirective supportive therapy (FE-NST) during 16 weeks. Over the course of treatment, adolescents in both groups experienced significant reductions in the rate of change in self-reported SI (ABFT: t = 12.61, p < 0.0001; effect size: d = 2.24) (FE-NST: t = 10.88, p < 0.0001; effect size: d = 1.93), but this decrease was not significantly greater in the ABFT group. In addition, in SI, between-group differences in remission on a 15-item self-report (SIQ-Jr <12) and response rates (≥50% decrease from baseline SIQ-Jr) were also not statistically significant over the intervention period. There were also no significant between-group differences in SA. It is noteworthy that a significantly higher percentage of adolescents in the FE-NST group reported a previous history of NSSI compared with the ABFT group, so these sample differences could condition the subsequent results of the interventions (67.6 vs 48.4%; χ2 = 4.82, p < 0.05) (Table 1b).

Family therapy

Systemic family therapy

In a large multicenter trial among adolescents referred to mental health services for repetitive SH, Cottrell et al. [37] compared family therapy (SHIFT) to TAU. Over the 6-month treatment period (5–8 sessions) and the 18-month follow-up, there were no statistically significant between-group differences in the repetition of SH (SA, NSSI) requiring hospital care. However, compared with TAU, SHIFT significantly reduced SI at 12-month follow-up (OR = 0.64; 95% CI: 0.44, 0.94; p = 0.024), but the effects were not maintained at 18-month follow-up.

To examine the long-term effectiveness of this manualized family therapy, Cottrell et al. [38] conducted an extended follow-up (18-36 months) and found no significant between-group differences in SH repetition rates during the extended follow-up period. In addition, adolescents aged 15-17 presented fewer repeated SH episodes compared with those aged 11–14 [hazard ratio (HR) = 0.7; 95% CI: 0.56, 0.88; p = 0.0019], with younger females being more likely to repeat SH (p = 0.022) (Table 1c).

Integrated family therapy

Based on their preliminary RCT [37], Asarnow et al. [39] conducted another trial to assess the efficacy of a 12-week cognitive-behavioral DBT-informed family program, Safe alternatives for teens & youths (SAFETY), compared with E-TAU in adolescents referred through different clinical settings. Survival analysis indicated a significantly higher probability of survival without SA by the 3-month follow-up in the SAFETY group compared with E-TAU (0.67, SE 0.14, Z = 2.45, p = 0.01) and for the overall survival curves (Wilcoxon χ2 = 5.81; p = 0.02). There were no statistically significant differences in the probability of survival without an NSSI between the two treatment groups.

Wijana et al. [40] conducted a preliminary evaluation of a 3-month manual-based treatment that included principles of FT, DBT, and CBT, called intensive contextual treatment for SH and Suicidality (ICT). Regarding the main variables, adolescents reported significant reductions in the frequency of SH (F = 10.91, p = 0.001; d = 0.54) and SA (F = 11.85, p < 0.0001; d = 1.38) pre/post-treatment. However, the intervention effect weakened from post-treatment to the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, and the mean frequency of SA was almost at the same levels as pretreatment (F = 11.85, p = 0.001; d = 1.03). The proportion of adolescents reporting SH at baseline was 71.2% and 54.3% at post-treatment, followed by a reduction at 6 months to 50.0% and 12 months to 30.8% (F = 1.52, p = 0.22; d = 0.20).

Finally, Ayer et al. [41] compared the effectiveness of individual (Adolescent community reinforcement approach, A-CRA, followed by assertive continuing care, ACC) versus family-based treatment (FBT) (multisystemic therapy, MST, and family support network, FSN) for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in adolescent substance users. Results showed a potentially positive trend for A-CRA on SI (from baseline to follow-up: 10.5 to 6.0%. Effect size = 0.15; 95% CI: −0.01, 0.38) and SA (from baseline to follow-up: 4.3 to 1.0%. Effect size = 0.14; 95% CI: −0.12, 0.41) and a small treatment effect of FBT on NSSI (from baseline to follow-up: 12.0 to 5.4%. Effect size = −0.06; 95% CI: −0.27, 0.11). However, the findings were not statistically significant (Table 1c).

Brief family-based therapy

In an RCT in adolescents presenting to the emergency department with suicidality, Wharff et al. [42] examined the efficacy of family-based crisis intervention (FBCI) compared with TAU. Over the course of the study, levels of suicidality decreased for all adolescents (F = 23.1, p < 0.001), but no statistically significant between-group differences were found after the intervention or at 1-month follow-up (Table 1c).

Support-based therapy

King et al. [43] conducted a study to examine whether Youth-Nominated Support Team Intervention for Suicidal Adolescents-Version II (YST-II) [44], is associated with lower mortality 11 to 14 years after psychiatric hospitalization for suicide risk. The HR indicated that those in the TAU group had a 6.6 times greater risk of death than those in the YST group (HR = 6.62; 95% CI: 1.49, 29.35, p < 0.01) (Table 1c).

Brief skills training

The period following hospital discharge is a critical time with a higher risk of suicide. Therefore, independent research groups specifically designed interventions to decrease the high risk during the transition from inpatient to outpatient care (Table 1d).

As Safe as Possible (ASAP) [45] is a brief inpatient intervention to reduce SA following discharge among adolescents hospitalized for suicidality. The intervention is supported by a telephone app (BRITE). After hospital discharge, BRITE provided access to a personalized safety plan, distress tolerance strategies, and emotion regulation skills. Based on their previous open trial, Kennard et al. [46] conducted an RCT to compare the efficacy of ASAP (added to TAU) versus TAU alone among adolescents hospitalized for SA or SI. The ASAP intervention did not have a statistically significant effect on SA or SI.

The coping long term with active suicide program (CLASP) is another intervention designed specifically for the critical post-discharge transition period. Based on prior findings in an adult population [47], Yen et al. [48] adapted the CLASP for adolescents (CLASP-A). To test the efficacy of this treatment program, the authors carried out an open pilot development trial and, subsequently, a pilot RCT. From baseline to 6-month follow-up, SA decreased for all adolescents, but there was no significant effect of the intervention.

In another trial, Rengasamy and Sparks (2019) [49] compared the effectiveness of two brief telephone interventions in reducing suicidal behavior post-hospitalization. Over a 3-month period, adolescents were assigned to either a single call intervention (SCI), consisting of one telephone contact, or a multiple call intervention (MCI), consisting of six telephone contacts. Findings indicate that patients receiving MCI report a significantly lower SA rate compared with SCI (6 vs 17%; OR = 0.28; 95% CI: 0.09, 0.93, p = 0.037).

Finally, Gryglewicz et al. [50] developed and evaluated linking individuals needing care (LINC), an intervention that includes strategies for suicide risk management and strategies to increase adherence and commitment to mental health services. Over the course of treatment, adolescents receiving LINC reported significant reductions in SA (OR = 0.46; 95% CI: 0.37, 0.57, p < 0.001) and SI (OR = −0.84; 95% CI: −0.92, −0.77, p < 0.001). In addition, the use of various beneficial services (individual therapy, medication management, and non-mental health supports) significantly increased at the end of the intervention (p < 0.05).

Motivational interviewing-based Intervention

This intervention has previously been included in other treatment packages. Recently, different research groups have developed interventions specifically focused on the motivational interview (Table 1d).

Grupp-Phelan et al. [51] tested the suicidal teens accessing treatment after an emergency department visit (STAT-ED), a brief intervention focused on motivational interviewing (MI). In an RCT in adolescents seen in the emergency department without psychiatric concerns but with suicide risk, STAT-ED was compared to E-TAU. There were no significant between-group differences either in SA or in SI at the 6-month follow-up period.

In a pilot RCT in adolescents hospitalized due to suicide risk, Czyz et al. [52] examined a motivational interview-enhanced safety planning intervention (MI-SafeCope). The intervention was compared with TAU including the recovery action plan. Despite findings indicating that adolescents in the MI-SafeCope reported significantly higher self-efficacy to refrain from SA (OR = 1.15; 95% CI: 0.11, 2.18, p = 0.030; Cohen’s d = 0.25), greater reliance on self to cope with SI (OR = 4.69; 95% CI: 1.06, 20.81, p = 0.042), and higher likelihood to use the safety plan and skills to manage suicidal thoughts (OR = 0.25; 95% CI: 0.08, 0.42, p = 0.004), there were no between-group differences in SA or SI severity (frequency and duration).

Extending this work, Czyz et al. [53] conducted a non-restricted pilot sequential, multiple assignment, randomized trial (SMART) to develop adaptive interventions for reducing suicide risk after hospitalization. During phase-1 intervention, adolescent inpatients were assigned to receive a Motivational Interview-Enhanced Safety Plan (MI-SP) alone or together with post-discharge text-based support, sent daily for four weeks and focusing on crisis management strategies. Subsequently, two weeks post-discharge, they were re-randomized in phase 2 to receive added booster calls or no calls. Over the course of treatment, adolescents in MI-SP + texts reported significantly lower intensity of SI compared with MI-SP alone (B = −0.59, p = 0.018; d = 0.39), but these differences were not maintained during phase 2 (booster calls versus no calls). Furthermore, at 1- and 3-month follow-up, neither intervention showed a significant effect on SI severity. In addition, adolescents in MI-SP + texts (phase-1) and booster calls (phase-2) reported a lower risk of SA and suicidal behavior 3 months post-discharge; however, there were no significant differences between treatment conditions.

Intensive community care service

Ougrin et al. [54] found that adolescents included in the supported discharge service (SDS) group, receiving an intensive community care service (ICCS), were significantly less likely to report multiple episodes of SH (five or more) at 6-month follow-up compared with inpatient TAU (24 vs 42%, OR = 0.18; 95% CI: 0.05, 0.64, p = 0.008). However, using the same sample, there was no between-group difference in the proportion of adolescents reporting any SH or presenting to the emergency department with serious SH (OR = 1.41; 95% CI: 0.45, 4.41, p = 0.560) [55] (Table 1d).

Integrative therapies

English et al. [56], developed the specialized therapeutic assessment-based recovery-focused treatment (START), which includes therapeutic assessment followed by one of the following modules: solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT) (4–6 sessions), CBT (8–16 sessions), or MBT-A (16–24 sessions), depending on adolescents’ needs and preferences. START significantly reduced the number of pre/post-treatment SH episodes [mean, (SD) = 7.93 (12.26) to 1.00 (1.47), p < 0.02]. With CBT, there was also a significant decrease in mean SH (p = 0.027). However, data were insufficient to prove the efficacy of SFBT or MBT-A alone (Table 1d).

Combination therapies

Joyce et al. [57] conducted a longitudinal cohort study of adolescents diagnosed with depression to determine the trajectories of 4 treatment patterns: no treatment, antidepressant monotherapy, psychotherapy as monotherapy (CBT), and dual therapy (antidepressant monotherapy plus CBT). The group receiving psychotherapy as monotherapy had the lowest incidence of SA during the 12-month assessment period and 12-month post-assessment period (0.5 per 100 person-years and 1.3 per 100 person-years, respectively). In contrast, the group receiving dual therapy showed high rates of SA across all periods (4.7– 7.1 per 100 person-years and 1.5–1.7 per 100 person-years, respectively) (Table 1d).

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review of psychological interventions for adolescents with suicidal behaviors, focusing specifically on SA. Over the years, increasingly comprehensive therapeutic interventions have proliferated, and research trying to prove their efficacy has been performed. However, to date, there are still few empirically validated psychological interventions to reduce suicide risk in this population.

Research has been conducted in various settings, testing a wide range of therapeutic approaches. Despite this, few studies were RCTs and many of them analyzed interventions originally designed for adults. Therefore, there is an urgent need for specific interventions for this stage of development, sensitive to the peculiarities of adolescence and ideally designed to take into account the point of view of such individuals. Furthermore, the inconsistency of many results obtained to date emphasizes the increasing need for higher-quality intervention studies in teenagers.

The review showed great variability in terms of the heterogeneous results obtained. Whilst some psychological interventions showed efficacy in reducing repeated SH at the end of treatment and even during follow-up, these effects were non-existent in other cases, with TAU reflecting performance similar to the experimental interventions themselves.

To date, DBT is the only effective treatment for adolescents with suicidal behaviors. Across all studies, components of DBT, as along with the duration and intensity of therapy, were distinctive features of this therapeutic approach. Recent research [3] has also reported that DBT is an intensive treatment that requires a significant time commitment for families and extensive training for the therapist. In fact, a lack of proficiency in delivering the intervention would be a barrier to guaranteed efficacy [21]. The interventions included in this group exhibit moderate heterogeneity and variable methodological quality. The use of different control interventions and recruitment strategies may explain this variability. On the one hand, some studies have used specific active control interventions [15] or provided E-TAU or additional alternatives [8, 12,13,14], while others used TAU [20, 21] or had no control group at all [16,17,18,19, 22]. Regarding longer term outcomes, one study [14] provides information on a 3-year follow-up period: DBT was superior in reducing SH in which hopelessness worked as a mediating factor of the effect of intervention on SH. Therefore, clinicians be aware of this and use specific techniques to treat hopelessness. With regard to recruitment strategies, some studies included both inpatient and outpatient adolescents [12], while others predominantly recruited less clinically severe outpatient adolescents [18, 23] or specifically focused on hospitalized adolescents [8, 20, 21]. Consistent with previous reviews and meta-analyses [7, 58, 59], DBT showed significantly better suicide-related outcomes with a moderate effect compared with active control interventions, while other therapeutic interventions did not show the same improvement.

The second-best group of psychotherapies in this review was CBT. In general terms, there was not enough evidence from current research to demonstrate that CBT reduces suicidal behaviors. Only one study proved a large effect for SA at 12-month follow-up. However, results should be interpreted cautiously, and a full RCT is needed to confirm these findings [28]. Replication of initial findings is important and often challenging, as previously demonstrated in the studies by Esposito-Smythers et al. [25, 60]. It should be noted that most studies utilized face-to-face therapy, but it would be interesting to explore the use of the Internet and mobile devices in adolescents with suicide-related behaviors. After the first online intervention among suicidal teens, Hetrick et al. [23] paved the way for a new generation of suicide intervention development. Our findings are in contrast to previous reviews, which found evidence of the efficacy of CBT in reducing suicidal thoughts and behaviors in adults [61] and teens [62,63,64]. However, consistent with a current review [65], more research is needed to replicate findings from CBT studies and to determine their impact on adolescents with suicidal behaviors. Additionally, it is necessary to determine how and for whom CBT would obtain better results.

Early findings from mentalizing therapies appear promising in treating adolescents with suicidal behaviors [29]. However, subsequent studies testing MBT-A obtained similar results to control treatments [30, 32, 33]. Family psychodynamic therapy was also more effective than TAU in the first trial [66]. However, when ABFT was compared with FE-NST, it did not perform significantly better than the active control group [39]. Further replication studies in diverse clinical samples are needed to validate the effects of psychodynamic interventions.

In contrast to previously described therapeutic interventions, family-focused therapies constitute a widely heterogeneous group. An important commonality of family therapies is that all of them recruited adolescents with a parent or caregiver willing to participate. Given that young people with stressful family factors are at greater risk of SH [65], family therapies have the potential to improve the family environment as well as parent-child relationships and, consequently, self-injurious behaviors. In fact, previous reviews and meta-analyses have shown that interventions that include a family component provide stronger evidence of efficacy [6, 62, 64]. Furthermore, the great heterogeneity in results may reflect the variety of interventions included in this group. Unfortunately, this variety limits the possibility of drawing reliable conclusions about the efficacy of this group of interventions, so more research is needed to better evaluate family therapies.

In contrast, non-family support intervention was generally no more effective than TAU. However, improved non-family support reduced deaths 14 years later [43]. These findings underscore the benefits of strengthening connections with supportive people, who can perform a protective function, which could have important implications for the development of suicide prevention strategies. Overall, awareness of the socio-family context is key in the treatment of adolescents with suicidal behavior.

Regarding brief skills training and motivational interviewing-based intervention, we concluded that developing and implementing rapid-acting psychological interventions in the first few weeks immediately after hospital discharge may determine long-term suicide risk reduction. In this sense, Bettis et al. [67] also suggest the need to develop strategies to facilitate the transition to these outpatient therapies, because one-third of patients do not complete the transition to post-discharge outpatient care.

Finally, the data we found demonstrate the efficacy of intensive community treatments for young people who are at high risk of SH [54, 55]. This intervention improves the abilities of adolescents to cope with stressful situations and constitutes a safe alternative to psychiatric hospitalization.

Limitations and strengths

This review has some methodological limitations. Firstly, the scope of the review, which focuses on the last 7 years, excludes studies published prior to 2016 in order to identify updated research. Second, the heterogeneity of the outcome measures and the different study assessment methods used greatly hinder the comparability of the data, making it difficult to determine the efficacy of interventions. Third, few longitudinal studies were found, and short follow-up periods were monitored; therefore, it is not possible to determine with certainty if the changes were the result of the treatment or natural self-recovery. On the other hand, sample sizes were occasionally small, and the representativeness of study participants was limited. In addition, the control or comparator treatments varied widely according to the theoretical approach, the intensity of the treatment, and the training of the therapists, and some trials lacked a control group. We acknowledge the diversity in comorbid psychiatric diagnoses and the frequent absence of information regarding concurrent pharmacotherapy as part of our study limitations. This recognition is crucial for understanding the complexity and variability of the study populations, which can influence the generalizability and applicability of the findings. Finally, the classification of interventions into broader treatment families does not follow an established consensus. Determining a standard approach is difficult as most interventions include multiple components and could be grouped into several categories. Despite these limitations, it should be noted that, on the one hand, the impact of suicide on adolescents and the consequent development of psychological interventions specifically designed for this population has taken on special importance in recent years and, on the other hand, we performed an exhaustive search in four databases, selecting the studies according to our inclusion criteria from more than two thousand articles. Finally, we followed the PRISMA guidelines; therefore, the methodology was rigorous. Also, to our knowledge, this is the first systematic review to focus on psychological interventions designed exclusively for adolescents with suicidal behaviors, focusing specifically on SA.

Future directions

The recent proliferation of studies on adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors notwithstanding, there are aspects that need to be improved. Firstly, an important area for future research is general training in prevention and early identification of warning signs. In such cases, prompt implementation of an effective treatment program can significantly reduce the risk of suicide, as suggested by Zalsman et al. [68]. When it comes to adolescents with existing severe SH, evidence suggests that psychological interventions have limited efficacy [69]. Therefore, there is a critical need to determine which treatments may work best for adolescents based on clinical severity and comorbid diagnosis. Furthermore, the universal conceptualization of suicidal behavior, emphasizing suicide attempts, as well as standardized criteria for “suicide recovery,” would allow for a more robust comparison among studies in order to determine the optimal treatment based on the characteristics in each case.

Another consideration is that few studies reported follow-up results and little is known about whether the effect achieved by psychological interventions post-treatment remains stable over time. These follow-up analyses are of particular importance in those interventions that show superiority over the control treatment but whose effects are attenuated in the follow-up, as long-term therapeutic gains are an important factor in determining the actual efficacy and are fundamental for therapeutic decisions.

It is noteworthy that pharmacological treatment is common in adolescents with suicide-related behaviors and psychiatric comorbidity. More than half of the participants in the studies received additional psychopharmacological treatment. However, few studies considered the combined effect of pharmacological treatment with psychotherapy. Despite this, some studies reported medication reduction or adherence as an outcome variable. More research is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of combination therapy approaches.

Despite the rise of the digital age, few trials used the Internet, social media, or mobile-apps. There is increasing evidence supporting the use of technology to treat mental disorders across the lifespan [70,71,72]. Indeed, a review has also highlighted the acceptability of social media use among adolescents at risk of suicide [73]. The use of “real-time” interventions delivered via mobile devices could help young people overcome their difficulties by providing access to peer support at critical moments [63]. Most studies of online interventions appear promising, raising the question of why online interventions are not more often included in clinical practice. In addition, it would be interesting to elucidate what type of interventions or elements thereof could be implemented through electronic devices.

Conclusion

There is growing interest in psychological interventions for adolescents with suicidal thoughts and behaviors as evidenced by the increasing numbers of publications on the topic in recent years. This review underscores the fact that the number of therapeutic interventions with sufficient empirical support is limited. Promising results have been found for CBT, family therapies, MBT, brief skills training, and motivational interviewing. However, only DBT produced empirical evidence in different RCTs conducted by independent research groups.

Future research should focus on improving the design of trials with the most promising interventions, as well as increasing scientific support for other therapeutic alternatives, such as brief psychological interventions for critical periods of high suicide risk. In addition, further investigations should analyze the combined effect of psychological and psychopharmacological interventions, and should incorporate new technologies as therapeutic tools for adolescents at risk of suicide.

References

Asarnow JR, Mehlum L. Practitioner review: treatment for suicidal and self-harming adolescents - advances in suicide prevention care. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60:1046–54.

Glenn CR, Kleiman EM, Kellerman J, Pollak O, Cha CB, Esposito EC, et al. Annual research review: a meta-analytic review of worldwide suicide rates in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61:294–308.

Clarke S, Allerhand LA, Berk MS. Recent advances in understanding and managing self-harm in adolescents. F1000Res. 2019;8:F1000 Faculty Rev-1794.

Katsivarda C, Assimakopoulos K, Jelastopulu E. Communication-based suicide prevention after the first attempt. A systematic review. Psychiatriki. 2021;32:51–58.

Haruvi Catalan L, Levis Frenk M, Adini Spigelman E, Engelberg Y, Barzilay S, Mufson L, et al. Ultra-brief crisis IPT-a based intervention for suicidal children and adolescents (IPT-A-SCI) pilot study results. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:553422.

Glenn CR, Esposito EC, Porter AC, Robinson DJ. Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019;48:357–92.

Kothgassner OD, Robinson K, Goreis A, Ougrin D, Plener PL. Does treatment method matter? A meta-analysis of the past 20 years of research on therapeutic interventions for self-harm and suicidal ideation in adolescents. Borderline Personal Disord Emot Dysregul. 2020;7:9.

Santamarina-Perez P, Mendez I, Singh MK, Berk M, Picado M, Font E, et al. Adapted dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with a high risk of suicide in a community clinic: a pragmatic randomized controlled trial. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2020;50:652–67.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71.

Howick J, Chalmers I, Glasziou P, Greenhalgh T, Heneghan C, Liberati A, et al. Explanation of the 2011 Oxford centre for evidence-based medicine (OCEBM) levels of evidence (Background Document). Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine. 2011. https://www.cebm.ox.ac.uk/resources/levels-ofevidence/explanation-of-the-2011-ocebm-levels-of-evidence.

Oremus M, Wolfson C, Perrault A, Demers L, Momoli F, Moride Y. Interrater reliability of the modified Jadad quality scale for systematic reviews of Alzheimer’s disease drug trials. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2001;12:232–6.

Mehlum L, Tørmoen AJ, Ramberg M, Haga E, Diep LM, Laberg S, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: a randomized trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2014;53:1082–91.

Mehlum L, Ramberg M, Tørmoen AJ, Haga H, Diep LM, Stanley BH, et al. Dialectical behavior therapy compared with enhanced usual care for adolescents with repeated suicidal and self-harming behavior: outcomes over a one-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55:295–300.

Mehlum L, Ramleth RK, Tørmoen AJ, Haga H, Diep LM, Stanley BH, et al. Long term effectiveness of dialectical behavior therapy versus enhanced usual care for adolescents with self-harming and suicidal behavior. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60:1112–22.

McCauley E, Berk MS, Asarnow JR, Adrian M, Cohen J, Korslund K, et al. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents at high risk for suicide: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:777–85.

Berk MS, Starace NK, Black VP, Avina C. Implementation of dialectical behavior therapy with suicidal and self-harming adolescents in a community clinic. Arch Suicide Res. 2020;24:64–81.

Hancock-Johnson E, Staniforth C, Pomroy L, Breen K. Adolescent inpatient completers of dialectical behaviour therapy. J Forensic Pract. 2020;22:29–39.

Flynn D, Kells M, Joyce M, Corcoran P, Gillespie C, Suarez C, et al. Innovations in practice: dialectical behaviour therapy for adolescents: multisite implementation and evaluation of a 16-week programme in a public community mental health setting. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2019;24:76–83.

Gillespie C, Joyce M, Flynn D, Corcoran P. Dialectical behaviour therapy for adolescents: a comparison of 16-week and 24-week programmes delivered in a public community setting. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2019;24:266–73.

Tebbett-Mock AA, Saito E, McGee M, Woloszyn P, Venuti M. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy versus treatment as usual for acute-care inpatient adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59:149–56.

Tebbett-Mock AA, McGee M, Saito E. Efficacy and sustainability of dialectical behaviour therapy for inpatient adolescents: a follow-up study. Gen Psychiatr. 2021;34:e100452.

Hiller AD, Hughes CD. Dialectical behavior therapy for adolescents: treatment outcomes in an outpatient community setting. Evidence Based Pract Child Adolesc Mental Health. (2022) https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2022.2056929.

Hetrick SE, Yuen HP, Bailey E, Cox GR, Templer K, Simon MR, et al. Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for young people with suicide-related behaviour (Reframe-IT): a randomised controlled trial. Evid Based Ment Health. 2017;20:76–82.

Högberg G, Hällström T. Mood regulation focused CBT based on memory reconsolidation, reduced suicidal ideation and depression in youth in a randomised controlled study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15:921.

Esposito-Smythers C, Wolff JC, Liu RT, Hunt JI, Adams L, Kim K, et al. Family-focused cognitive behavioral treatment for depressed adolescents in suicidal crisis with co-occurring risk factors: a randomized trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;60:1133–41.

Esposito-Smythers C, Hadley W, Curby TW, Brown LK. Randomized pilot trial of a cognitive-behavioral alcohol, self-harm, and HIV prevention program for teens in mental health treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2017;89:49–56.

Goldston DB, Curry JF, Wells KC, Kaminer Y, Daniel SS, Esposito-Smythers C, et al. Feasibility of an integrated treatment approach for youth with depression, suicide attempts, and substance use problems. Evid Based Pract Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2021;6:155–72.

Duarté-Vélez Y, Jimenez-Colon G, Jones RN, Spirito A. Socio-cognitive behavioral therapy for latinx adolescent with suicidal behaviors: a pilot randomized trial. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2022; https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-022-01439-z.

Rossouw TI, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment for self-harm in adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51:1304–13.e3.

Griffiths H, Duffy F, Duffy L, Brown S, Hockady H, Eliasson E, et al. Efficacy of Mentalization-based group therapy for adolescents: the results of a pilot randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:167.

Karterud S. Manual for mentaliseringsbasert psykoedukativ gruppeterapi (MBT-I). Gyldendal akademisk (2011).

Beck E, Bo S, Jørgensen MS, Gondan M, Poulsen S, Storebø OJ, et al. Mentalization-based treatment in groups for adolescents with borderline personality disorder: a randomized controlled trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61:594–604.

Jørgensen MS, Storebø OJ, Bo S, Poulsen S, Gondan M, Beck E, et al. Mentalization-based treatment in groups for adolescents with borderline personality disorder: 3- and 12-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30:699–710.

Bo S, Sharp C, Beck E, Pedersen J, Gondan M, Simonsen E. First empirical evaluation of outcomes for mentalization-based group therapy for adolescents with BPD. Personal Disord. 2017;8:396–401.

Diamond GS, Wintersteen MB, Brown GK, Diamond GM, Gallop R, Shelef K, et al. Attachment-based family therapy for adolescents with suicidal ideation: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:122–31.

Diamond GS, Kobak RR, Krauthamer Ewing ES, Levy SA, Herres JL, Russon, et al. A randomized controlled trial: attachment-based family and nondirective supportive treatments for youth who are suicidal. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2019;58:721–31.

Cottrell DJ, Wright-Hughes A, Collinson M, Boston P, Eisler I, Fortune S, et al. Effectiveness of systemic family therapy versus treatment as usual for young people after self-harm: a pragmatic, phase 3, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:203–16.

Cottrell DJ, Wright-Hughes A, Eisler I, Fortune S, Green J, House AO, et al. Longer-term effectiveness of systemic family therapy compared with treatment as usual for young people after self-harm: an extended follow up of pragmatic randomised controlled trial. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;18:100246.

Asarnow JR, Hughes JL, Babeva KN, Sugar CA. Cognitive-behavioral family treatment for suicide attempt prevention: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2017;56:506–14.

Wijana MB, Enebrink P, Liljedahl SI, Ghaderi A. Preliminary evaluation of an intensive integrated individual and family therapy model for self-harming adolescents. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:371.

Ayer L, Pane JD, Godley MD, McCaffrey DF, Burgette L, Cefalu M, et al. Comparative effectiveness of individual versus family-based substance use treatment on adolescent self-injurious thoughts and behaviors. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;139:108782.

Wharff EA, Ginnis KB, Ross AM, White EM, White MT, Forbes PW. Family-based crisis intervention with suicidal adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35:170–5.

King CA, Arango A, Kramer A, Busby D, Czyz E, Foster CE, et al. Association of the youth-nominated support team intervention for suicidal adolescents with 11- to 14-year mortality outcomes: secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:492–8.

King CA, Klaus N, Kramer A, Venkataraman S, Quinlan P, Gillespie B. The youth-nominated support team-version II for suicidal adolescents: a randomized controlled intervention trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:880–93.

Kennard BD, Biernesser C, Wolfe KL, Foxwell AA, Craddock Lee SJ, Rial KV, et al. Developing a brief suicide prevention intervention and mobile phone application: a qualitative report. J Technol Hum Serv. 2015;33:345–57.

Kennard BD, Goldstein T, Foxwell AA, McMakin DL, Wolfe K, Biernesser C, et al. As safe as possible (ASAP): a brief app-supported inpatient intervention to prevent postdischarge suicidal behavior in hospitalized, suicidal adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:864–72.

Miller IW, Gaudiano BA, Weinstock LM. The coping long term with active suicide program: description and pilot data. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2016;46:752–61.

Yen S, Spirito A, Weinstock LM, Tezanos K, Kolobaric A, Miller I. Coping long term with active suicide in adolescents: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2019;24:847–59.

Rengasamy M, Sparks G. Reduction of postdischarge suicidal behavior among adolescents through a telephone-based intervention. Psychiatr Serv. 2019;70:545–52.

Gryglewicz K, Peterson A, Nam E, Vance MM, Borntrager L, Karver MS. Caring transitions - a care coordination intervention to reduce suicide risk among youth discharged from inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. Crisis. 2023;44:7–13.

Grupp-Phelan J, Stevens J, Boyd S, Cohen DM, Ammerman RT, Liddy-Hicks S, et al. Effect of a motivational interviewing-based intervention on initiation of mental health treatment and mental health after an emergency department visit among suicidal adolescents: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1917941.

Czyz EK, King CA, Biermann BJ. Motivational interviewing-enhanced safety planning for adolescents at high suicide risk: a pilot randomized controlled trial. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2019;48:250–62.

Czyz EK, King CA, Prouty D, Micol VJ, Walton M, Nahum-Shani I. Adaptive intervention for prevention of adolescent suicidal behavior after hospitalization: a pilot sequential multiple assignment randomized trial. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;62:1019–31.

Ougrin D, Corrigall R, Poole J, Zundel T, Sarhane M, Slater V, et al. Comparison of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an intensive community supported discharge service versus treatment as usual for adolescents with psychiatric emergencies: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:477–85.

Ougrin D, Corrigall R, Stahl D, Poole J, Zundel T, Wait M, et al. Supported discharge service versus inpatient care evaluation (SITE): a randomised controlled trial comparing effectiveness of an intensive community care service versus inpatient treatment as usual for adolescents with severe psychiatric disorders: self-harm, functional impairment, and educational and clinical outcomes. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021;30:1427–36.

English O, Wellings C, Banerjea P, Ougrin D. Specialized therapeutic assessment-based recovery-focused treatment for young people with self-harm: pilot study. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:895.

Joyce NR, Schuler MS, Hadland SE, Hatfield LA. Variation in the 12-month treatment trajectories of children and adolescents after a diagnosis of depression. JAMA Pediatr. 2018;172:49–56.

Kothgassner OD, Goreis A, Robinson K, Huscsava MM, Schmahl C, Plener PL. Efficacy of dialectical behavior therapy for adolescent self-harm and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med. 2021;51:1057–67.

Nawaz RF, Reen G, Bloodworth N, Maughan D, Vincent C. Interventions to reduce self-harm on in-patient wards: systematic review. BJPsych Open. 2021;7:e80.

Esposito-Smythers C, Spirito A, Kahler CW, Hunt J, Monti P. Treatment of co-occurring substance abuse and suicidality among adolescents: a randomized trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2011;79:728–39.

Mewton L, Andrews G. Cognitive behavioral therapy for suicidal behaviors: improving patient outcomes. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2016;9:21–9.

Ougrin D, Tranah T, Stahl D, Moran P, Asarnow JR. Therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54:97–107.e2.

Cox G, Hetrick S. Psychosocial interventions for self-harm, suicidal ideation and suicide attempt in children and young people: what? how? who? and where?. Evid Based Ment Health. 2017;20:35–40.

Iyengar U, Snowden N, Asarnow JR, Moran P, Tranah T, Ougrin D. A further look at therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: an updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:583.

Esmaeili ED, Farahbakhsh M, Sarbazi E, Khodamoradi F, Gaffari Fam S, Azizi H. Predictors and incidence rate of suicide re-attempt among suicide attempters: a prospective study. Asian J Psychiatr. 2022;69:102999.

Asarnow JR, Berk M, Hughes JL, Anderson NL. The SAFETY program: a treatment-development trial of a cognitive-behavioral family treatment for adolescent suicide attempters. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2015;44:194–203.

Bettis AH, Liu RT, Walsh BW, Klonsky ED. Treatments for self-injurious thoughts and behaviors in youth: progress and challenges. Evid Based Pract Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2020;5:354–64.

Zalsman G, Hawton K, Wasserman D, Heeringen K, Arensman E, Sarchiapone M, et al. Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:646–59.

Fox KR, Huang X, Guzmán EM, Funsch KM, Cha CB, Ribeiro JD, et al. Interventions for suicide and self-injury: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials across nearly 50 years of research. Psychol Bull. 2020;146:1117–45.

Proudfoot J, Clarke J, Birch MR, Whitton AE, Parker G, Manicavasagar V, et al. Impact of a mobile phone and web program on symptom and functional outcomes for people with mild-to-moderate depression, anxiety and stress: a randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:312.

Nordh M, Wahlund T, Jolstedt M, Sahlin H, Bjureberg J, Ahlen J, et al. Therapist-guided internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy vs internet-delivered supportive therapy for children and adolescents with social anxiety disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:705–13.

Rees CS, Anderson RA, Kane RT, Finlay-Jones AL. Online obsessive-compulsive disorder treatment: preliminary results of the “OCD? Not me!” self-guided internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy program for young people. JMIR Ment Health. 2016;3:e29.

Robinson J, Cox G, Bailey E, Hetrick S, Rodrigues M, Fisher S, et al. Social media and suicide prevention: a systematic review. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2016;10:103–21.

Acknowledgements

This work was partly supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Ref. PI19/01027, PI23/01277) and co-funded by the European Union, Government of the Principality of Asturias (Ref. PCTI 2021-2023 IDI/2021/111), “la Caixa” Foundation (Ref. HR23-00421 CaixaResearch Health 2023), CIBERSAM - Consorcio Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red Salud Mental- (CB/07/09/0020 Group), Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and Unión Europea – European Regional Development Fund. However, the funding sources had no influence on this study. Ainoa Garcia Fernandez thanks Instituto de Salud Carlos III for its PFIS grant (FI20/00318), and Clara Martínez-Cao also thanks the Ministry of Science, Innovation and Universities for its FPU grant (FPU19/01231).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TB-B, PAS, MPG-P, and JB designed the study. All authors reviewed and approved the design. AG-F performed the data extraction, and MTBB and PAS assisted in the data selection and extraction. AG-F, TB-B, MPG-P, and PAS wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors reviewed all drafts and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

García-Fernández, A., Bobes-Bascarán, T., Martínez-Cao, C. et al. Psychological interventions for suicidal behavior in adolescents: a comprehensive systematic review. Transl Psychiatry 14, 438 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-024-03132-2

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-024-03132-2

This article is cited by

-

Dialectical behavior therapy combined with parental support in adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury: a randomized controlled trial

Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health (2026)