Abstract

As a leading cause of adolescent death, suicidal and self-injurious related behaviors (SSIRBs) is a devastating global health problem, particularly among patients with psychiatric disorders (PDs). Previous studies have shown that multiple interventions can alleviate symptoms and reduce risks. This review aimed to provide a systematic summary of interventions (i.e., medication, physical therapy, psychosocial therapy) for the treatment of SSIRBs among Chinese adolescents with PDs. From inception to September 17, 2023, twelve databases (PubMed, CINAHL, ScienceDirect, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Clinical Trial, Web of Science, CEPS, SinoMed, Wanfang and CNKI) were searched. We qualitatively and quantitatively synthesized the included studies. Standardized mean differences (SMDs), risk ratios and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) used the Der Simonian and Laird random-effects model. Fifty-two studies covering 3709 eligible participants were included. Overall, the commonly used interventions targeting SSIRBs and negative feelings in PDs adolescents with SSIRBs included psychosocial therapy (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy), medication (e.g., antidepressants), and physiotherapy (e.g., repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation). Importantly, quetiapine fumarate in combination with sodium valproate (SV) had positive effects on reducing self-injury behaviors score [SMD: −2.466 (95% CI: −3.305, −1.628), I2 = 88.36%], depression [SMD: −1.587 (95% CI: −2.505, −0.670), I2 = 90.45%], anxiety [SMD: −1.925 (95% CI: −2.700, −1.150), I2 = 85.23%], impulsivity [SMD: −2.439 (95% CI: −2.748, −2.094), I2 = 0%], as well as its safety in comparison with SV alone. No significant difference of adverse reactions was found by low-dose QF (P > 0.05). This review systematically outlined the primary characteristics, safety and effectiveness of interventions for Chinese PDs adolescents with SSIRBs, which could serve as valuable evidence for guidelines aiming to formulate recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Suicidal and self-injurious related behaviors (SSIRBs) is a devastating global health problem, particularly among patients with psychiatric disorders (PDs) [1, 2]. One or more than one in three patients diagnosed with mood disorders have attempted to suicide [3]. As a leading cause of adolescent death [4], approximately 11 to 43 percent of adolescents with PDs have been diagnosed with SSIRBs, such as non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI), suicidal ideation (SI), self-injurious behavior (SIB), suicidality and suicide attempts (SA), etc [5,6,7,8]. SSIRBs invariably lead to negative outcomes in adolescents with PDs [9], including alcohol and drug abuse [10], cognitive impairments, poor interpersonal relationships [11], and violent crimes [12], which even increase the medical burden [13]. The 2019 Global Burden of Disease Study found that self-harm contributes to 319.6 years of life lost, per one hundred thousand population [14]. PDs may contribute to the occurrence of SSIRBs [10, 15]. A systematic review reported that 58% of Chinese adolescents with major depressive disorder (MDD) had NSSI [16]. The suicide rate among patients with mood disorders was approximately 6–10%, 10 times higher than that of non-psychiatric patients [17, 18]. As the most extreme manifestation of PDs, SSIRBs not only increases the risk of PDs, but also aggravates the severity of PDs [19, 20]. The rapid socialization process, the distinct traditional Chinese culture and the highly unbalanced distribution of treatment resources have a certain influence on the occurrence of SSIRBs in Chinese adolescents with PDs [21,22,23,24]. Considering the above conditions, it is urgent to explore effective interventions for Chinese adolescents who experienced SSIRBs and PDs [3].

Early studies have shown that interventions for adolescents with PDs affected by SSIRBs can alleviate symptoms and reduce risk. For example, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) showed positive improvements in emotional dysregulation, depression, and symptoms related to suicidal and self-injurious behaviors among adolescents with borderline personality disorders (BPD) and SSIRBs [25]. In addition, intermittent theta burst stimulation has been shown to reduce SI in adolescents with MDD [26]. On the other hand, anti-suicidal effects of medications (e.g. ketamine) have also been observed in adolescents with MDD and SSIRBs [27,28,29]. Overall, a variety of effective interventions were available for adolescents with PDs and SSIRBs. Numerous reviews and meta-analyses on individual interventions have been published [30,31,32,33]. However, there have been few reviews of drug therapy for PDs adolescents with SSIRBs. For example, a meta-analysis among adolescents reported that family therapy could significantly improve the outcome of SI rather than depression [30]. Another review showed that DBT was effective in simultaneously improving NSSI and depression in adolescents [31]. Also, two articles indicated the effectiveness of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in treating MDD with SI [32, 34].

To date, two comprehensive systematic reviews have summarized the effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for NSSI or SSIRBs. Lu JJ et al. found cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to be the most common among psychosocial therapy, which is effective for SSIRBs in Chinese adolescents [35]. Qu DY et al. summarized the prevalence, risk factors, and interventions of NSSI among Chinese adolescents in a scoping review [1]. However, several considerations need to be made. First, more comprehensive databases and more precise search strategies should be used; Second, the existing systematic reviews targeting Chinese adolescents focused only on NSSI or SSIRBs but ignored comorbid PDs; Third, drug and physical therapies were not included.

Notably, this is the first study to examine a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions for SSIRBs in Chinese adolescents with PDs. Our study aims to systematically summarize the interventions (i.e., medication, physical therapy, psychosocial therapy) for SSIRBs in Chinese adolescents with PDs. This endeavor has the potential to develop more meaningful strategies for the treatment of SSIRBs associated with PDs. It is proving particularly valuable in promoting the integration of intervention methods into clinical practice and guiding the improvement of clinical guidelines.

Methods

This meta-analysis was pre-registered in the International Platform of Registered Systematic Review and Meta-analysis Protocols (INPLASY; registration number: 202350069) and conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement.

Eligibility criteria and measurement

In accordance with the PICOS tool, the inclusion criteria were defined as follows: Participants (P): Chinese with PDs (e.g., MDD) and SSIRBs (e.g., NSSI, SI, SA); adolescents aged 18 years old and below or the sum of average age and SD ≤ 18 years old [36]. Intervention (I): psychosocial therapy (e.g., CBT); pharmacological therapy (e.g., antidepressants); physical therapy (e.g., rTMS). Comparison (C): no-treatment control or active control. Outcomes (O): effectiveness; and Study design (S): qualitative studies (QSs), randomized controlled trials (RCTs), clinical controlled trials (CCTs), pre-post studies, case reports (CRs). No language limitation was conducted. The primary outcomes included the average score and standard deviation (SD) derived from assessments using the SSIRBs scale, such as the Ottawa self-injury inventory (OSI). Secondary outcomes were the rate of adverse reactions (ADRs), effective rate, as well as mean and SD of scores on other symptom scales, such as self-rating depression scale (SDS); self-rating anxiety scale (SAS), etc.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Literature searching in twelve databases (PubMed, CINAHL, ScienceDirect, PsycINFO, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, Clinical Trial, Web of Science, CEPS, SinoMed, Wanfang and CNKI) was independently carried out by two groups of reviewers (group 1: J.J.L., J.H. and W.T.G.; group 2: Z.X.W., N.Y., Y.B.L. and J.X.G.). The literature searching was conducted from inception to January 31, 2023 and an updating was from January 31 to September 17, 2023. Followed by a review [37], subject and free terms were used: (“auto mutilat*“OR “cutt*“ OR “headbang*“ OR “overdos*“ OR “selfdestruct*“ OR “selfharm*“ OR “selfimmolat*“ OR “selfinflict*“ OR “selfinjur*“ OR “selfpoison*“ OR “suicid*“ OR “suicide, attempted” OR “suicidal ideation”) AND (“adolescent” OR “teen” OR “youth” OR “teenager”) AND (“China” OR “Chinese”). The search terms used for databases were recorded in the Supplementary Figs. 21–29. The titles and abstracts were independently reviewed and the full texts of relevant publications were scrutinized by the same two groups of reviewers. Any inconsistencies were resolved through consultation with a senior reviewer (WIP.P.). Additional studies were identified through manual search among citations in the included articles, previous systematic reviews, and meta-analyses [31, 38,39,40,41]. Moreover, we also searched conference papers from the 21st National Conference on Psychiatry and the 17th National Conference on Child and Adolescent Psychiatry of the Chinese Medical Association [42, 43].

Data extraction

Relevant data was independently extracted by two groups of reviewers based on a predesigned Excel data collection sheet. Data included: first author, year of survey and publication, survey province, study type, sampling method, sample size, types of interventions in the control and experimental groups, parameters of drug therapy and physical therapy, setting, intervention duration, types of SSIRBs, types of PDs, age range, mean and SD of participants age, number and proportion of males, definitions of SSIRBs and PDs, and measurements. According to a classification of psychological interventions [44], a new set of psychological interventions were defined as ten categories, including CBT, relationship-based interventions, systemic interventions, psychoeducation, group work with children, psychotherapy, counselling, peer mentoring, intensive service models, and activity-based therapies. Two reviewers (KIG.L. and W.W.R.) independently confirmed the accuracy of the data through a double-check process. Discrepancies were resolved through consultation with an additional reviewer (WIP.P.).

Quality assessment

RCTs were evaluated by the Jadad scale [45]. The overall score varied between 0 and 5 points. The Jadad score of 2 or lower was categorized as low quality, while those with 3 or higher were classified as high quality. CCT studies (0–16 points) and pre-post studies (0–12 points) were assessed using two different version of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) tailored quality assessment tool [46], which was widely used in previous systematic reviews [47,48,49]. The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) of qualitative studies checklist was used (0–10 points) [50], which was commonly found in some early studies [51,52,53], while the JBI Critical Appraisal Checklist was utilized for CRs (0–8 points) [54]. Higher scores denoted superior reporting. The evidence level for primary and secondary outcomes was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology. According to the evaluation rules, all outcomes can be classified into four categories: very low, low, moderate, or high [55, 56]. Also, the quality of our review was assessed using A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews, version 2 (AMSTAR 2) checklist [57], which included 16 items; each item is given one point if the criterion is met, or a zero point if the criterion is not met, is unclear, or is not applicable. Finally, a total score was categorized into four levels: critical low (0–4 points), low (5–8 points), moderate (9–11 points), and high (12–16 points) [58, 59]. Study quality was independently assessed by two reviewers (W.W.R. and J.J.L.). Discrepancies were resolved through consultation with an additional reviewer (KIG.L.).

Statistical analysis

Qualitative synthesis

The study and intervention characteristics, and outcomes of the effectiveness for multiple interventions were synthesized. Combination therapies are defined as the utilization of two or more different types of interventions, whereas physical therapy, psychosocial therapy and drug therapy were considered as a single intervention.

Meta-analysis

Due to the limited number of included studies, two or more RCT articles with the same characteristics were considered for the meta-analysis: 1. patients with SSIRBs; 2. patients with PDs; 3. relevant assessments. Without involving any comparative intervention, a no-treatment control is served as a neutral comparison for study groups receiving the treatment under investigation. In contrast, the active control involves the integration of a proven intervention into the control group, which is compared with an experimental treatment. Considering the differences in sampling methods, demographic profiles, and assessment tools across studies, the symptom estimates (e.g., self-injurious behavior score, depression score) were presented as standardized mean differences (SMDs) and rate [e.g., effective rate and incidence rate of ADRs] with risk ratio (RRs) and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) by using the Der Simonian and Laird random-effects model [60]. Between-study heterogeneity was estimated using Cochran’s Q test and the I2 statistic, with an I2 ≥ 50% or Cochran’s Q of p < 0.05 indicating significant heterogeneity [61]. The Egger’s test, Begg’s test and the trim-and-fill method were used to assess publication bias when the number of literature was more than two [62]. The significance level was set at 0.05 (two-tailed). Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the outlier studies. Meta-analyses were performed using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, Version 2.

Results

Study characteristics

A total of 20,926 articles were retrieved from the databases and other sources. Following the removal of duplicate records and the use of automation tools for preliminary exclusion, 10,976 records would be used for screening at the first stage. Through initially reviewing the titles and abstracts, 716 records were identified and selected for full-text retrieval for the second stage of screening. With full-text screening, fifty-two articles contained fifty-three studies with 3709 participants (experimental group = 2034 adolescents vs control group = 1675 adolescents) (Fig. 1) [43, 63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107,108,109,110,111,112]. Out of ten articles from international databases, forty-two literatures were from Chinese databases. Twenty-eight (28/53, 53.8%) referred to NSSI. There was no eligible literature from Hong Kong and Macao, with the exception of one study from Taiwan. The majority of studies were distributed in Mainland China (Fig. 2a), mainly in coastal areas and publications showed a decreasing trend from coastal to inland areas. Generally, approximately 55% of therapies (29 in 53) were combination therapies. Physical therapy (e.g., rTMS and ECT) was included in 14 studies, while drug therapy (e.g., antidepressants and antipsychotics) was included in 37 of 53 studies. Additionally, 31 studies included seven psychosocial interventions [e.g., intensive service provision (ISP) and CBT] (Fig. 2b). Forty-eight studies were conducted for MDD adolescents, while 2 were conducted for autism spectrum disorders (ASD), 1 for first episode (FE)-BD, and 2 for multi-PDs. Only 11 studies reported medical records with a diagnosis of FE-MDD, with six of those studies utilized combination therapy. The most common therapy both in non-FE-MDD (32.4%) and in FE-MDD (36.4%) was pharmacological combined psychosocial therapy with no significant difference between two groups (X2 < 0.001, P = 1.000). Besides, physical therapy was exclusively employed as a monotherapy in non-FE-MDD, but not observed in patients with FE-MDD.

a Provincial distribution of 51 included studies (52 included reports). Note: There is a study without reporting experimental address [112], and the distribution map is based on 52 reports from the remaining 51 studies. b Interventions for PDs with SSIRBs. Note: Mix(1) means multiple drugs; Mix(2) means PDs; This figure is presented based on the intervention strategies of the experimental group. ABT Activity-based therapy, AD Antidepressants, AE Antiepileptic, AP Antipsychotic, ASD Autism spectrum disorder, BD Bipolar disorder, CBT Cognitive-behavioral therapy, GWWC Group work with children, ISP Intensive service provision, MDD Major depressive disorder, MS Mood stabilizer, NSSI Nonsuicidal self-injury, PC Psychotherapy, PDs Psychiatric Q6 disorders, PM Pharmacological intervention, PH Physical intervention, PS Psychosocial intervention, PE Psychoeducational intervention, RBI Relationship-based intervention, SIB Self-injurious behavior, SI Suicide ideation, SA Suicide attempts, ST Suicidal tendencies, SSIRBs Suicidal and self-injurious related behaviors.

Assessment quality and outcome evidence

Thirty-four RCTs used the Jadad scale, with 29 studies rated as high quality. The main reason for the low quality of the other 5 studies was the inappropriate method of randomization sequence. The quality of 11 CCTs ranged from 5–9 points, and the mean score was 7.2 points. One QS, 4 CRs and 2 pre-post studies were assessed, respectively. Nine studies accounted for more than half of the total score (Table 1). A high quality (12 points) of systematic review was identified by the AMSTAR-2 (Supplementary Table 1). Since all studies we included in the meta-analysis were RCTs, we initially rated four stars. There were some limitations in these RCTs, such as high heterogeneity, risk of bias, and small sample sizes. Given the large effect size, most of the evidence quality were at a medium to low level (Supplementary Table 2).

Major depressive disorder with single behavior

Non-suicidal self-injury

Single therapy

Nine studies were conducted during the COVID-19 epidemic. As of 2021, the number of publications in the next year was about twice as high as in the previous year. Patients were either from inpatient (IP) or outpatient (OP) settings, while 4 studies enrolled subjects without further explanation of the source. The duration of the intervention was between 4 and 12 weeks in eight studies. In four studies, three criteria were used to assess NSSI, namely the ANSAQ, adolescent self-harm scale (ASHS), and the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders -V (DSM-V). In addition, 3 out of 9 studies diagnosed MDD in hospitals, 4 studies used 3 types of indicators, with 1 study using the international classification of diseases-10 (ICD-10), 1 study using the Chinese classification of mental disorders-3 (CCMD-3), and 2 studies using the DSM-V. Others used the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI-kid) and a guideline [113], respectively. Seven RCTs were high quality (mean score = 3), while one CCT study was rated as 7 and one pre-post study was rated as 8.

In eight studies, the scores of the Hamilton depression scale (HAMD) or a reduced rate were used to assess the effectiveness of the interventions. The remaining studies used the self-rating questionnaire for adolescent (SQAPMPU) and the screen for child anxiety related-emotional disorders (SCARED) to assess depressive and anxious symptoms, respectively. Only one study used transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) to the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC), with pseudo-stimulation as control. Compared to pre-intervention, the HAMD-17 score and ASHS decreased significantly (P < 0.05). And the effectiveness was greater in the tDCS group, and no ADR was reported.

Six of the nine studies focused on pharmacotherapy, which was a common approach. Apart from one no-treatment control, 2 studies with sertraline and 3 studies with sodium valproate (SV) were routinely considered as control groups. Two studies used magnesium valproate (MV) and sertraline, respectively, and no ADR was reported. However, four studies reported the occurrence of nausea and weakness after taking quetiapine fumarate (QF). In four studies, the risk of self-injury decreased significantly after the intervention (P < 0.05). Six studies reported a significant alleviation of depression, anxiety, and impulsivity after the intervention using HAMD-17, symptom checklist-90 (SCL-90), etc. (P < 0.05).

Two of nine studies were psychosocial interventions that could be assigned to more than one psychosocial category. CBT was flexibly combined with ISP, a psychoeducational intervention, and no ADR was reported. Zhu P et al. indicated a significant difference in the reduction rate of NSSI (experimental group: 14.29% vs control group: 46.51%, P < 0.01). The significant improvement was also seen in the adolescents’ depressive symptoms, self-efficacy, and life satisfaction (all P < 0.05). Lu HL et al. also reported a similar improvement effect in the teenagers’ mobile phone dependence, anxiety symptoms, and depressive symptoms (all P < 0.05).

Combined therapies

Seventeen studies were published between 2021 and 2023, of which Li HZ et al. conducted a comparison among 3 groups. Twelve high-quality RCTs with ratings between 3 and 5 were included. In addition, three CCTs received an average rating of 7, with one CR scoring 7. The study durations in hospital was between 2 and 12 weeks. Except for five studies that did not report diagnostic criteria, seven studies assessed MDD using DSM-V, while 5 studies used ICD-10. In addition, the functional assessment of self-mutilation (FASM), the self-injury behavior screening scale (SBSS), the OSI, and the ANSAQ were used to assess the risk of self-injury. Furthermore, 6 studies reported ADRs.

Twelve of the seventeen studies were psychosocial therapy in combination with pharmacotherapy, 3 studies used physical and pharmacological combination therapies. And 2 studies includes three types of therapies. Seventeen studies indicated a significant reduction in self-injury or suicide risk, and depression after the intervention. In addition, negative emotions (e.g., impulsivity and anxiety) as well as cognitive functioning and social support also were improved.

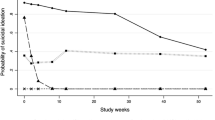

Meta-analysis

Compared with no-treatment control group, CBT in combination with antidepressants showed significant benefits for depression (SMD = −1.467; 95%CI = −2.492–−0.442, I2 = 88.39%, P < 0.001) and anxiety (SMD = −2.101; 95%CI = −3.869–−0.333, I2 = 95.18%, P < 0.001). Neither the Egger’s nor the Begg’s-tests (all P-values > 0.05) revealed any publication bias. In particular, the pooled SMD value remained consistent regardless of the exclusion of any individual study (Supplementary Figs. 12–18). Considering that there are two similar CCT studies, we conducted an additional sensitivity analysis to combine CCT and RCT studies and the findings indicated consistent conclusions. Sensitivity analysis found that CBT in combination with antidepressants indicated significant benefits for depression (SMD = −1.436; 95%CI = −2.158–−0.713, I2 = 85.33%, P < 0.001; Supplementary Figs. 19–20). However, Xi Y et al. used two depression scales. When the HAMD was replaced to Montgomery-Asberg depression rating scale (MADRS), the score was still significant (SMD = −1.254; 95%CI = −1.959–−0.550, I2 = 85.32%, P < 0.001). Neither the Egger’s nor the Begg’s-tests (all P-values > 0.05) revealed any publication bias.

However, CBT and antidepressants showed a significant effect compared to the active control on depression (SMD = −0.943; 95%CI = −1.414–−0.472, I2 = 33.38%, P = 0.212) and anxiety (SMD = −0.942; 95%CI = −1.323–−0.560, I2 = 0%, P = 0.592). When the HAMD-24 was replaced by the PHQ-9, there was still a significant difference, namely for depression (SMD = −0.905; 95%CI = −1.361–−0.450, I2 = 29.44%, P = 0.236). In addition, Peng HZ et al. replaced the HAMA-14 with generalized anxiety disorder scale-7, and found a similar result for anxiety (SMD = −0.971; 95%CI = −1.354–−0.589, P < 0.05, I2 = 0%, P = 0.592). Furthermore, no publication bias was detected by the Egger’s and the Begg’s-tests (all P-values > 0.05, Table 2). Moreover, significant advantages were found in emotion regulation (SMD = −0.832; 95%CI = −1.342–−0.322, I2 = 0%, P = 0.820).

In comparison with no-treatment control group, the aggregated SMD value of depressive symptom scores was found [−1.587 (95% CI: −2.505, −0.670), P < 0.05]. Considerable heterogeneity was reported (I2 = 90.45%, P < 0.05), as well as no publication bias (Begg’s test: Z = 1.567, P = 0.117; Egger’s test: Z = 4.746, P = 0.132). The combined SMD of anxiety symptom scores was found [−1.925 (95% CI: −2.700, −1.150), P < 0.05]. The results suggested high heterogeneity (I2 = 85.23%, P = 0.001). Nevertheless, no publication bias was detected (Begg test: Z = 1.567, P = 0.117; Egger test: Z = 1.053, P = 0.484). In addition, the combined RR value for clinical effectiveness was found [−1.204 (95% CI: 1.084, 1.338), P < 0.05]. No heterogeneity was found (I2 = 0%, P = 0.810). However, we found publication bias (Begg’s test: Z = 1.567, P = 0.117; Egger’s test: Z = 17.263, P = 0.037), with an adjusted RR value [1.167 (95% CI: 1.069, 1.273), P < 0.05]. Significant relief of impulsivity was found [−2.439 (95% CI: −2.748, −2.094), P < 0.05], while no heterogeneity was detected (I2 = 0%, P = 0.989). In addition, statistically significant positive effects were observed for SIB [−2.466 (95% CI: −3.305, −1.628), P < 0.05], with heterogeneity (I2 = 88.36%, P = 0.017).

Contrary to our expectations, no significant difference was observed in the incidence rate of ADRs after QF and SV, with nausea/vomiting [1.194 (95% CI: 0.357, 3.992), I2 = 0%, P = 0.668], dizziness/vertigo [0.864 (95% CI: 0.292, 2.556), I2 = 0%, P = 0.704], xerostomia [1.043 (95% CI: 0.352, 3.092), I2 = 0%, P = 0.729]. A publication bias was found in nausea/vomiting (Begg’s test: Z = 1.567, P = 0.117; Egger’s test: Z = 34.540, P = 0.018). In addition, increased BMI [1.217 (95% CI: 0.382, 3.870), P > 0.05] and drowsiness/drowsiness/fatigue [1.150 (95% CI: 0.281, 4.713), P > 0.05] were not detected with significance, nor was heterogeneity (P > 0.05, Table 2). The overall SMD value remained consistent regardless of the exclusion of any individual study (Supplementary Figs. 2–11).

Suicidal ideation

As shown in Table 3, six of the seven studies were conducted between 2017 and 2022, with four published in 2023 and two in 2022. For one study in 2018, the date of the study was not specified. Four studies were IPs and one study was OPs. The mean trial duration was approximately 3.3 weeks and ranged from 1 to 6 weeks. For the assessment of MDD, 7 studies used ICD-10, MINI-kid, DSM-V or DSM-IV, respectively. To define SI, 4 studies used the Beck scale for suicide ideation (BSSI); 1 study used the self-rating idea of suicide scale (SIOSS-26); 1 study used both the Columbia suicide severity rating scale (C-SSRS) and the BSSI; and 1 study used the SI item of HAMD. With an average rating of over 3, 3 RCTs were high quality, while another RCT was rated as 2. In addition, 1 CR was rated as 8, while the other 2 CCTs were rated as 7 and 8, respectively.

With the exception of one study that only used esketamine, the others were combination therapies. The HAMD was widely used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms, while suicide risk was assessed using the BSSI, HAMD-SI and C-SSRS, etc. ECT was applied in 2 studies and resulted in significant improvement in SI and depressive symptoms. In one study, it was observed that high-frequency rTMS showed greater efficacy in the early improvement of MDD than low-frequency rTMS (χ2 = 8.167, P < 0.01). The difference in SI between the two groups was statistically significant (low-frequency group: 36.7% vs. high-frequency group: 63.3%, P < 0.05). No ADR was reported. Similarly, Pan F et al. reported positive effect of high-frequency rTMS for depression and suicide risk, with 2 participants experiencing hypomania. Three adolescents experienced drowsiness after each rTMS but without other subjective side effects.

In comparison with sertraline, DBT was combined with sertraline in two studies, which showed a significant therapeutic effect, and no ADR was reported. The total BSSI score, SI intensity and suicide risk decreased after the intervention (P < 0.01). In addition, two studies showed very similar efficacy on depressive symptoms, with 1 study (experiment vs. control = 89.47% vs. 63.16%, P < 0.05), and the other (experiment vs control = 92.86% vs. 70.00%, P < 0.05).

The use of midazolam was associated with fewer adverse effects, particularly nausea, dissociation, etc., by Zhou YL et al. However, significant differences were observed in the mean changes of C-SSRS scores for ideation and intensity from baseline to day 6 between the esketamine group and the midazolam group.[ideation, 2.6 (SD = 2.0) vs. 1.7 (SD = 2.2), P < 0.01; intensity, 10.6 (SD = 8.4) vs. 5.0 (SD = 7.4), P < 0.01]. The response rates of antidepressants at 4 weeks post-treatment between esketamine and midazolam were 61.5% versus 52.5%. No significant difference in mania symptoms between the two groups was detected (χ2 = 0.384, P > 0.05).

Self-injurious behavior

Five studies have been published in the last three years. Two of the four RCTs were rated as high quality, the other 2 RCTs received 2 each, while the only CCT was rated 9. Three studies used psychosocial therapy alone, while the other two studies used antidepressants with ISP or high frequency rTMS. All studies were conducted in hospital. HAMD was used in 4 studies, while only 1 study used SDS. SIB lasting longer than 5 days or 6 weeks was categorized as SIB in two of five studies, while the others were identified as medical records. In addition, three studies used CCMD-2-R and ICD-10. Overall, both depression and self-injury were alleviated after the intervention. In addition, the combination of ISP and relationship-based intervention resulted in higher adherence compared to the control group.

Meta-analysis

Only the depressive symptoms were summarized in two studies with no-treatment control were aggregated, which included a total of 93 samples. The combined SMD value of depressive symptom score was [−1.647 (95% CI: −2.474, −0.820)]. Significant heterogeneity was observed (I2 = 81.10%, P = 0.021, Table 2). The exclusion of a single study did not change the stability of the aggregated SMD value (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Suicidal tendencies

Four studies were included, three of which had a duration of 2 years and one of which had a duration of 3 years. One study was published in 2013, the others were published in the last 3 years. One study used the DSM-V, while three studies were based on medical records. In the absence of a suitable randomization method, the quality of two RCTs was 2 and 3, respectively. Nevertheless, two CCT studies both scored 7.

Psychosocial therapy was used alone. Wang CL et al. showed significant difference in HAMD and HAMA scores between two groups at both 2 and 4 weeks after the intervention (P < 0.01). Zhu L et al. used cognitive correction and behavioral shaping nursing to intervene with MDD patients with suicidal tendencies. Symptoms, psychological status, and cognitive functioning improved after the interventions(P < 0.05). Shao HH et al. demonstrated the combination of CBT and ISP could significantly reduce depressive symptoms and suicide-related score (P < 0.001). In addition, the combination of CBT and ISP showed significant improvement in quality of life [psychological (χ2 = 14.83, P < 0.001), physical (χ2 = 10.35, P < 0.005), physiological (χ2 = 10.92, P < 0.001) and social functions (χ2 = 15.61, P < 0.001)]. Su M et al. reported that quality of life, sleep quality and depression improved significantly after implementation of the clinical characteristics analysis and nursing strategies (CCANS)(P < 0.05). Specifically, compared with control group, CCANS significantly reduced rates of cutting wrist (9.52% vs. 0%, P < 0.05), jumping (14.29% vs. 4.76%, P < 0.05), poison ingestion (14.29% vs. 4.76%, P < 0.05) and overall suicidal rate (38.09% vs. 9.52%, P < 0.05). Importantly, no ADR was reported in these 4 studies.

Suicidality

Quan LJ et al. conducted a high quality RCT of FE-MDD, with sensory integration therapy and sertraline in 2020. The study lasted a total of 12 weeks and several evaluations were conducted. A significant difference in ISI score was found between 2 groups after the intervention (experimental:4.52 ± 1.02 vs. control: 5.27 ± 1.06, P < 0.01). The positive number of SI decreased after sensory integration therapy (baseline vs. week 4 vs. week 8 vs. week 12 = 40 vs. 24 vs. 15 vs 5), with a significant difference found in total ADRs, nausea (experimental: 2/40 vs. control: 4/40), drowsiness (experimental: 1/40 vs. control: 3/40), and dizzy (experimental: 3/40 vs. control: 5/40).

Major depressive disorder with multi-behaviors

Five studies applied a single therapy for MDD with multiple behaviors, including 3 of 5 simultaneously studied SSIRBs. Five different scales were used to assess the severity of SSIRBs, including BSSI, SIOSS, clinical global impression scale severity (CGI-S), suicide-visual analog scale (SVAS). Due to the high dropout rate, one CCT was rated as 5 [102]. In addition, the lack of rigorous double-blind studies and randomization methods were the main reasons for the low quality (2 vs. 3) in two RCTs. One pre-post study was rated as 8, while one CR was rated as 7 and one CCT was rated as 5. Four out of five studies were conducted in hospital. The mean trial duration ranged from 10 days to 2 months.

Non-major depressive disorder with SSIRBs

Five studies were conducted: two for ASD with SIB, one for FE-BD with NSSI, one for PDs with SI and one for PDs with SIB. Two of five studies used DSM-V and DSM-IV. On average, one article has been published every two years since the study was established in 2016. The quality of two studies was 9 for QS and 5 for CR, respectively. The other 2 studies were rated as high quality according to the Jadad scale (mean score = 3). One CCT was rated as 8. One study did not specify the source of the sample, the other 4 studies were from IPs or OPs. The average intervention duration was 7.3 weeks, while 2 studies did not specify the duration.

Four out of five studies were single therapy, with only one study using rTMS and SSRIS. Only one study adopted a novel online psychoeducational intervention for MDD adolescents. Duan SQ et al. found that transcripts of semi-structured interviews reduced instances of deliberate self-harm by providing acceptable support to adolescents. One CR reported that traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) and the five elements of music therapy significantly improved the child’s sleep and emotions, and SIB was also alleviated. Li XD et al. found that aripiprazole had a significant effect on alleviating the occurrence of NSSI in FE-BD compared to lithium (week 8: experimental: 1/38 vs. control: 8/38, P < 0.05) with similar incidence rates of ADRs. Only one study used rTMS with different intensities to affect the left or right DLPFC. Good relief effects were observed for SI, with 22 of 29 adolescents recovering. In contrast, a negative correlation was observed between improvements in HAMD total score and HAMD-SI score (r = −0.094, P = 0.629).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this was the inaugural systematic review and meta-analysis to summarize the characteristics of interventions for Chinese PDs adolescents with SSIRBs. Geographically distributed along the coast, all studies were located far from underdeveloped areas, highlighting the uneven distribution of mental health resources in China [23]. Nevertheless, almost all of the literature was published in the past four years, with 2 studies in 2020, 9 studies in 2021, and 19 studies in 2022. Notably, the growth trend of publications indicates a tremendous research enthusiasm during the COVID-19 pandemic [114]. ISP and CBT were the most common psychosocial strategies, while the most commonly used medication was antidepressants. In addition, rTMS was the most common physical therapy.

Given the prevailing global circumstances, each of the three major intervention strategies has its own merits and drawbacks. The Times and the Guardian noted that “antidepressants do more harm than good” and “psychiatric drugs are doing us more harm than good” [115]. And antidepressants have been given a black box warning by the Food and Drug Administration, suggesting that they may have an increased risk of suicide in adolescents with PDs [116]. All phenomena have also had unseen negative effects on drug treatment. As a substitute for drug therapy, psychosocial therapy not only circumvents the potential hazards arising from insufficient evidence of efficacy but also mitigates the occurrence of many ADRs which would be a risk factor for COVID-19 complications [117]. From another perspective, the delayed therapeutic response of psychological therapy was also a recognized disadvantage [92]. As a newly explored intervention, physical therapy has been gradually promoted in recent years, whose advantages are fewer ADRs and rapid response [80, 118]. Therefore, three types of existing interventions were comprehensively integrated in our study, which could facilitate the optimization of resource allocation and the improvement of effectiveness.

Psychosocial intervention

Psychosocial therapy was used in 31 studies, representing 7 of 10 major categories of psychological interventions [44]. Our study suggests that psychosocial therapy was effective, which is consistent with international studies for adolescents with PDs and SSIRBs [11, 30]. However, as the majority of studies involved combination therapies and considered psychosocial therapy as a complementary approach [119,120,121], it is a challenging to precisely determine the source of therapeutic effectiveness [122].

To date, the effectiveness of CBT and antidepressants in PDs or SSIRBs has been widely recognized [123,124,125]. Our study suggests that CBT in combination with antidepressants can alleviate symptoms of depression, anxiety, and difficulty in emotion regulation, which is superior to active control. In addition, our result indicated that the experimental group with a no-treatment control seemed to have a stronger effect. Although it has been suggested in the past that patients with and without antidepressant medication derived similar benefits from CBT in terms of anxiety [126, 127], the combination of CBT and sertraline was more effective in relieving anxiety and depression than either treatment alone [128, 129], which is consistent with our findings. The decrease in NSSI and alleviation of depression in adolescents were reported after DBT, which was considered as comprehensive CBT [31]. Another RCT confirmed the positive efficacy of DBT in combination with medication in reducing SA in adolescents with BD [130]. Similar to their findings, our study also found that CBT with antidepressants could decrease self-injury behaviors score in Chinese adolescents with PDs. Lu JJ and colleagues have reported that CBT is the most commonly used intervention for the treatment of SSIRBs in Chinese adolescents [35]. However, our results suggest that ISP has an almost equivalent status with CBT in adolescents with PDs and comorbid SSIRBs. CBT focuses on an individual’s psychological and behavioral patterns to achieve a transformation personal control [35]. ISP achieves therapeutic goals by providing comprehensive and highly focused support with attachment and object relations [131]. Additionally, the cultivation of skills not reflected in CBT is integrated into this process and includes the development of self-esteem and the navigation of interpersonal relationships [44]. On the other hand, more conflictual relationships were observed in the families of adolescents with PDs and SSIRBs [132]. Ebrahimi et al. applied parent–child interactions and observed a reduction in depressive symptoms [133], which was also found in our study that demonstrated the positive effectiveness against depression in PGPC. In summary, psychosocial intervention is a promising therapeutic approach.

Online interventions are very popular, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Buronfosse et al. demonstrated the effects of hotlines in reducing self-aggressive behavior in patients diagnosed with BPD [134]. Effectiveness in suicide prevention and symptoms improvement has also been reported [135,136,137]. Although SMS text messaging interventions were first introduced as a productive novel approach in the treatment of Chinese PDs adolescents with SSIRBs [94], the effectiveness was similar to previous studies, with SMS text messaging interventions showing promising potential due to their cost-effectiveness, low-intensity, and widespread acceptability [94, 135]. The importance of psychosocial therapy is essential that it goes beyond symptom management and addresses the complex interplay of psychological, social, and environmental factors. It is an integral part of the holistic treatment of adolescents struggling with mental health problems associated with SSIRBs.

Physical intervention

In our studies, three types (i.e., ECT, tDCS, and rTMS) of non-invasive brain stimulation (NBS) were applied [138], which were feasible and demonstrated to be effective in Chinese adolescents. Although Bloch and colleagues reported that rTMS treatment did not significantly alleviate the severity of SI in MDD adolescents [139], most of studies have confirmed the role of rTMS in alleviating SI in MDD adults [140, 141], our results supported this effectiveness on Chinese adolescents [72, 77, 79]. The factors leading to the differences could be the effects of comorbidities and previous history of ECT were not excluded by Bloch et al. whose study included only 9 participants. However, there is a recognized mechanism that may explain the efficacy of ECT. Cortical inhibition may be enhanced by rTMS, possibly by modulating GABAB receptor-mediated activity, leading to a reduction in SI among depression patients [77, 142]. A weak positive effect on stress-related emotions was found after tDCS treatment [143]. While tDCS was able to significantly alleviate depressive symptoms in our study, which was also shown by Charvet et al. [144]. Furthermore, the alleviation of suicidal symptoms and depression after ECT was demonstrated in our study, which was also found in previous results [145, 146]. The pathogenesis of PDs with SSIRBs has been linked to neurochemical metabolic processes [147], HPA axis dysfunction, and psychosocial factors [148]. By applying external magnetic fields or electric currents to the brain, NBS induces changes in neuronal excitability, thereby affecting cerebral metabolism and neuronal electrical activity [149], with the aim of alleviating symptoms [64, 68].

Contact dermatitis was observed after tDCS with a parameter control above or below 2 mA [150], while no ADR was observed at a current of 1–2 mA. Appropriate parameters may be an associated factor for ADRs. In addition, physical therapy combined with drug treatment had a lower proportion of ADRs than the group receiving drug treatment alone [92, 103]. Therefore, NBS was one of the options for the treatment of Chinese PDs adolescents with SSIRBs. Furthermore, ECT was traumatizing, while both tDCS and ECT had difficulties in accurately determining the location of the stimulus effect. However, today’s technology can analyze data in real time and automatically adapt the stimuli to the behavioral state of the brain [151]. This can not only improve controllability and safety, but also increase confidence in the treatment. In the future, the combination of artificial intelligence and targeted electrical brain stimulation offers endless possibilities [152, 153].

Pharmacotherapy

This is the inaugural meta-analysis investigating the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy (antipsychotics and antiepileptics, antidepressants and CBT) in adolescents with MDD and NSSI. Our study showed that QF and sodium valproate (SV) had positive effects on the relief of depressive symptoms, anxiety, impulse symptoms, and self-injury symptoms, as well as safety, compared to SV alone.

There is ample evidence in the literature that defects in gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transmission are associated with MDD [154], while the main neurophysiological basis of MDD is related to dopamine [155]. SV not only prevents the degradation of GABA by inhibiting GABA aminotransferase [156], but also increases the activity of glutamic acid decarboxylase [157], which is the rate-limiting enzyme for the synthesis of GABA [158]. Thus, SV increases brain GABA concentrations and modulates the neuronal. QF is an antagonist with moderate affinity for adrenergic a1 and a2 receptors, serotonergic 5-hydroxytryptamine 2 receptors (5-HT2 receptors) and dopaminergic D2 receptors; the affinity for serotonergic 5-HT1A receptors is low [159]. By antagonizing 5-HT2A receptors, acting as a partial agonist of 5-HT1A receptors, and antagonizing α2 adrenoceptors, QF increases the release of dopamine from the prefrontal cortex [160]. Based on the potential mechanisms, SV and QF may have an effect on improving anxiety and depressive symptoms [161]. Furthermore, in practice, SV has been shown to be the first choice for the drug treatment of BD, while QF served as a complementary strategy for PDs due to its safety [161]. Previous studies have reported the role of QF in reducing impulsivity and depression [162, 163], which was also reflected in our results. Our study also found a reduction in self-injury scores after taking QF and SV, whereas other studies have reported a similar role for these drugs [164, 165]. In addition, our study showed that the incidence of ADRs was slightly higher than when taking SV alone, but no significant difference, suggesting that the ADRs caused by low-dose QF were still within an acceptable range. The efficacy, optimal dosage, and compliance of other medications (e.g., ketamine) should be further investigated.

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review and meta-analysis included databases from international and Chinese sources to conduct a comprehensive literature search and use of sophisticated analyses. We described the characteristics of interventions in Chinese PDs adolescents with SSIRBs, and presented meta-analyses for both NSSI and SIB. Our study also included psychosocial, pharmacologic, and physical treatments. In addition, our review also included gray papers from top conferences in Chinese psychiatry.

However, it is important to note some limitations. First, the results should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of studies. Second, except for MDD adolescents with NSSI or SIB, our study did not conduct a meta-analysis of interventions for other SSIRBs in adolescents with PDs due to insufficient data. Third, our study was limited to focusing primarily on interventions and overlooking preventive strategies while using a promising risk calculator for early detection of SA in BD [166]. Fourth, optimal doses and medication compliance were not analyzed due to insufficient data. Finally, comparisons in our study were not possible due to the different components and efficacy of pharmacotherapy in the included studies. Since the articles studied were primarily from Mainland China, the generalizability of these results to other ethnicities may be limited.

Conclusions

This systematic review described the main characteristics, safety and effectiveness of interventions in Chinese PDs adolescents with SSIRBs. Single therapy and combination therapies have shown varying degrees of safety and effectiveness in relieving symptoms. These findings expanded the means and theoretical basis of mental health treatment to provide benefits for future health care utilization and the economy as a whole. Larger extensive, multicenter RCTs with large sample sizes are needed to evaluate efficacy and safety.

References

Qu D, Wen X, Liu B, Zhang X, He Y, Chen D, et al. Non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese population: a scoping review of prevalence, method, risk factors and preventive interventions. Lancet Reg Health West Pac. 2023;37:100794. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2023.100794

Zhong B-L, Xu Y-M, Zhu J-H, Liu X-J. Non-suicidal self-injury in Chinese heroin-dependent patients receiving methadone maintenance treatment: prevalence and associated factors. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2018;189:161–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.05.006

Dervic K, Sher L, Galfalvy HC, Grunebaum M, Burke AK, Sullivan G, et al. Antisuicidal effect of lithum in bipolar disorder: is there an age-specific effect? J Affect Disord. 2023;341:8–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.08.107

Wasserman D, Carli V, Iosue M, Javed A, Herrman H. Suicide prevention in childhood and adolescence: a narrative review of current knowledge on risk and protective factors and effectiveness of interventions. Asia Pac Psychiatry. 2021;13:e12452. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12452

Widnall E, Epstein S, Polling C, Velupillai S, Jewell A, Dutta R, et al. Autism spectrum disorders as a risk factor for adolescent self-harm: a retrospective Cohort study of 113,286 young people in the UK. BMC Med. 2022;20:137. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02329-w

Dickerson Mayes S, Calhoun SL, Baweja R, Mahr F. Suicide ideation and attempts in children with psychiatric disorders and typical development. Crisis. 2015;36:55–60. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000284

Storch EA, Sulkowski ML, Nadeau J, Lewin AB, Arnold EB, Mutch PJ, et al. The phenomenology and clinical correlates of suicidal thoughts and behaviors in youth with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2013;43:2450–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1795-x

Mayes SD, Gorman AA, Hillwig-Garcia J, Syed E. Suicide ideation and attempts in children with autism. Res Autism Spectr Disord. 2013;7:109–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2012.07.009

Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Nicholson WK, Cabana M, Chelmow D, Coker TR, et al. Screening for depression and suicide risk in children and adolescents: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. Jama. 2022;328:1534–42. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.16946

Hawton K, Casañas ICC, Haw C, Saunders K. Risk factors for suicide in individuals with depression: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2013;147:17–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.004

Waraan L, Rognli EW, Czajkowski NO, Mehlum L, Aalberg M. Efficacy of attachment-based family therapy compared to treatment as usual for suicidal ideation in adolescents with MDD. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2021;26:464–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104520980776

Castro Moreno LS, Fuertes Valencia LF, Pacheco García OE, Muñoz Lozada CM. Risk factors associated with suicide attempt as predictors of suicide, Colombia, 2016–2017. Rev Colomb Psiquiatr. 2023;52:176–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcpeng.2021.03.005

Kieling C, Buchweitz C, Caye A, Silvani J, Ameis SH, Brunoni AR, et al. Worldwide prevalence and disability from mental disorders across childhood and adolescence: evidence from the Global Burden of Disease study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.5051

Castelpietra G, Knudsen AKS, Agardh EE, Armocida B, Beghi M, Iburg KM, et al. The burden of mental disorders, substance use disorders and self-harm among young people in Europe, 1990–2019: findings from the Global Burden of Disease study 2019. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;16:100341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100341

Dong M, Lu L, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Ungvari GS, Ng CH, et al. Prevalence of suicide attempts in bipolar disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;29:e63. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796019000593

Niu HM, Zhang ZM, Mu XM, Zhao HJ. The characteristics and influencing factors of nonsuicidal self-injury of adolescents with depressive disorder in china: a meta-analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2023;211:448–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/nmd.0000000000001641

Andrea C, Keith H, Sarah S, John RG. Lithium in the prevention of suicide in mood disorders: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ: Br Med J. 2013;346:f3646. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.f3646

Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:205–28. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.170.3.205

Angelakis I, Gooding P, Tarrier N, Panagioti M. Suicidality in obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;39:1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.03.002

Diaconu G, Turecki G. Panic disorder and suicidality: is comorbidity with depression the key? J Affect Disord. 2007;104:203–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.03.006

Al-Sharifi A, Krynicki CR, Upthegrove R. Self-harm and ethnicity: a systematic review. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2015;61:600–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764015573085

Stack S. Contributing factors to suicide: political, social, cultural and economic. Prev Med. 2021;152:106498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106498

Wu JL, Pan J. The scarcity of child psychiatrists in China. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:286–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(19)30099-9

Zhong BL, Chan SSM, Liu TB, Chiu HF. Nonfatal suicidal behaviors of Chinese rural-to-urban migrant workers: attitude toward suicide matters. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2019;49:1199–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12519

Fleischhaker C, Böhme R, Sixt B, Brück C, Schneider C, Schulz E. Dialectical Behavioral Therapy for Adolescents (DBT-A): a clinical trial for patients with suicidal and self-injurious behavior and borderline symptoms with a one-year follow-up. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2011;5:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-5-3

Zhao Y, He ZL, Luo W, Yu Y, Chen JJ, Cai X, et al. Effect of intermittent theta burst stimulation on suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in adolescent depression with suicide attempt: a Randomized Sham-Controlled study. J Affect Disord. 2023;325:618–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.061

Weber G, Yao J, Binns S, Namkoong S. Case report of subanesthetic intravenous ketamine infusion for the treatment of neuropathic pain and depression with suicidal features in a pediatric patient. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2018;2018:9375910. https://doi.org/10.1155/2018/9375910

Ionescu DF, Bentley KH, Eikermann M, Taylor N, Akeju O, Swee MB, et al. Repeat-dose ketamine augmentation for treatment-resistant depression with chronic suicidal ideation: a randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:516–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.09.037

Marshall R, Valle K, Sheridan D, Kothari J. Ketamine for treatment-resistant depression and suicidality in adolescents: an Observational study of 3 cases. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2023;43:460–2. https://doi.org/10.1097/jcp.0000000000001730

Waraan L, Siqveland J, Hanssen-Bauer K, Czjakowski NO, Axelsdóttir B, Mehlum L, et al. Family therapy for adolescents with depression and suicidal ideation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023;28:831–49. https://doi.org/10.1177/13591045221125005

Cook NE, Gorraiz M. Dialectical behavior therapy for nonsuicidal self-injury and depression among adolescents: preliminary meta-analytic evidence. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2016;21:81–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12112

Mehta S, Konstantinou G, Weissman CR, Daskalakis ZJ, Voineskos D, Downar J, et al. The effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on suicidal ideation in treatment-resistant depression: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2022;83:21r13969. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.21r13969

Croarkin PE, Nakonezny PA, Deng ZD, Romanowicz M, Voort JLV, Camsari DD, et al. High-frequency repetitive TMS for suicidal ideation in adolescents with depression. J Affect Disord. 2018;239:282–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.06.048

Chen GW, Hsu TW, Ching PY, Pan CC, Chou PH, Chu CS. Efficacy and tolerability of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on suicidal ideation: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:884390. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.884390

Lu J, Gao W, Wang Z, Yang N, Pang WIP, In Lok GK, et al. Psychosocial interventions for suicidal and self-injurious-related behaviors among adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis of Chinese practices. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1281696. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1281696

Geoffroy MC, Bouchard S, Per M, Khoury B, Chartrand E, Renaud J, et al. Prevalence of suicidal ideation and self-harm behaviours in children aged 12 years and younger: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:703–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00193-6

Hawton K, Witt KG, Taylor Salisbury TL, Arensman E, Gunnell D, Townsend E, et al. Interventions for self-harm in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD012013. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD012013

Kang P, Sun N, Liu P, Wang B. Research progress of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in treatment of non-suicidal self-injury behavior in adolescents with depression. J Bio-education. 2022;10:493–7. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2095-4301.2022.06.012

Gao JB. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the treatment of non-suicidal self-injury in depressed adolescents (in Chinese). China J Health Psychol. 2020;28:1738–43. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp.2020.11.029

Li YL, Ran LY, Ai M, Kuang L. Systematic evaluation of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescent depressive patients (in Chinese). Chin J Behav Med Brain Sci. 2020;29:567–71. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.cn371468-20200415-01259

Bridge JA, Iyengar S, Salary CB, Barbe RP, Birmaher B, Pincus HA, et al. Clinical response and risk for reported suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in pediatric antidepressant treatment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 2007;297:1683–96. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.297.15.1683

Luo DL. Effect of transcranial direct current stimulation on non-suicidal self-injury behavior in adolescents with depressive disorders. The 21st National Conference on Psychiatry and the 17th National Conference on Child and Adolescent Psychiatry of the Chinese Medical Association. 2023; p 1116. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1000-8039.2023.18.109

Zhu L, Zhang R. Clinical characteristics, cognitive correction, and behavioral shaping nursing effects of depressive adolescents with suicidal tendency. The 21st National Conference on Psychiatry and the 17th National Conference on Child and Adolescent Psychiatry of the Chinese Medical Association. 2023; p1038. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1000-8039.2023.18.109

Macdonald G, Livingstone N, Hanratty J, McCartan C, Cotmore R, Cary M, et al. The effectiveness, acceptability and cost-effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for maltreated children and adolescents: an evidence synthesis. Health Technol Assess. 2016;20:1–508. https://doi.org/10.3310/hta20690

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-2456(95)00134-4

National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Study quality assessment tools-controlled intervention studies and before-after (pre-post) studies with no control group. 2021. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed 17 August 2023)

Arnoldy L, Gauci S, Young LM, Marx W, Macpherson H, Pipingas A, et al. The association of dietary and nutrient patterns on neurocognitive decline: a systematic review of MRI and PET studies. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;87:101892. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.arr.2023.101892

Langevin R, Kenny S, Kern A, Kingsland E, Pennestri MH. Sexual abuse and sleep in children and adolescents: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;64:101628. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2022.101628

Pineros-Leano M, Liechty JM, Piedra LM. Latino immigrants, depressive symptoms, and cognitive behavioral therapy: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2017;208:567–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.025

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2023). CASP Qualitative Studies checklist. [online]. 2022. Available at: https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018.pdf (accessed 17 August 2023).

Batstone E, Bailey C, Hallett N. Spiritual care provision to end-of-life patients: a systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29:3609–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15411

Gebremeskel AT, Omonaiye O, Yaya S. Multilevel determinants of community health workers for an effective maternal and child health programme in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. 2022;7:e008162. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-008162

Harris R, Kavaliotis E, Drummond SPA, Wolkow AP. Sleep, mental health and physical health in new shift workers transitioning to shift work: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2024;75:101927. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smrv.2024.101927

The Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewers’ Manual: 2016 edition. Australia: The Joanna Briggs Institute; 2016.

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. Bmj. 2008;336:924–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

Ma YM, Yuan MD, Zhong BL. Efficacy and acceptability of music therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2024;15:2342739. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008066.2024.2342739

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. Bmj. 2017;358:j4008. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.j4008

Wilhelmsen NC, Eriksson T. Medication adherence interventions and outcomes: an overview of systematic reviews. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2019;26:187–92. https://doi.org/10.1136/ejhpharm-2018-001725

Sharif MO, Janjua-Sharif FN, Ali H, Ahmed F. Systematic reviews explained: AMSTAR-how to tell the good from the bad and the ugly. Oral Health Dent Manag. 2013;12:9–16.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2010;1:97–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.12

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ: Br Med J. 2003;327:557–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557

Valentine JC, Pigott TD, Rothstein HR. How many studies do you need? A primer on statistical power for meta-analysis. J Educ Behav Stat. 2010;35:215–47. https://doi.org/10.3102/1076998609346961

Xi Y, Gao HY, Zhu YX, Ge WT, Shen ZZ. Effect observation of drugs combined with cognitive behavioral therapy in adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury depression (in Chinese). Chin Community Dr. 2023;39:31–3. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-614x.2023.05.011

Li X, Chen XL, Zhou Y, Dai LQ, Cui LB, Yu RQ, et al. Altered regional homogeneity and amplitude of low-frequency fluctuations induced by electroconvulsive therapy for adolescents with depression and suicidal ideation. Brain Sci. 2022;12:1121. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12091121

Wang XR, Wang K, Zhao JJ, Tong QH, Zhang XL. Effect of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with sertraline on self-injurious behavior in adolescents with depression (in Chinese). Anhui Med J. 2023;44:501–5. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000-0399.2023.05.002

Wang Q, Huang H, Xu T, Dong X. Intensive rTMS treatment for non-suicidal self-injury in an adolescent treatment-resistant depression patient: a case report. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;88:103740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103740

Li ZJ, Peng GH. Clinical efficacy of quetiapine combined with sodium valproate sustained-release tablets in the treatment of adolescent depression patients with non-suicidal self injury (in Chinese). Mod Med Health Res. 2023;7:64–6. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2096-3718.2023.08.021

Chen X, Fu Y, Zou Q, Zhang Y, Qin X, Tian Y, et al. A retrospective case series of electroconvulsive therapy in the management of depression and suicidal symptoms in adolescents. Brain Behav. 2022;12:e2795. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2795

Tang YT, Zhu XQ, Ling Z, Nong XS. Analysis of the effect of parent-child group combined psychological counseling nursing on adolescents with depression and self-injury behavior (in Chinese). Fu You Hu Li. 2023;3:2120–3. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.2097-0838.2023.09.034

Ma JH. Correlation between magnesium valproate combined with sertraline to improve non-suicidal self-injury behavior and HPG and HPT axes in adolescents with depression (in Chinese). Jining Medical University. Shandong. 2023.

Wan DY, Dong XX, Li SC. Analysis of the efficacy of DBT combined with sertraline in the treatment of adolescent depressive patients with suicidal ideation (in Chinese). Guide China Med. 2023;21:49–52. https://doi.org/10.15912/j.cnki.gocm.2023.21.035

Zhang Y. Study on the effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on the acute treatment of depressive disorders and suicidal ideation in first-episode childhood adolescent (in Chinese). Jining Medical University. Shandong. 2023.

Zhou Y, Lan X, Wang C, Zhang F, Liu H, Fu L, et al. Effect of repeated intravenous esketamine on adolescents with major depressive disorder and suicidal ideation: a randomized active-placebo-controlled trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2024;63:507–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2023.05.031

Duan DA, Deng Y, Zhang ZX, Gu ZL. Effect of dialectical behavior therapy combined with sertraline on adolescent depression disorder with non-suicidal self-injury (in Chinese). Clin Focus. 2023;38:319–23. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1004-583X.2023.04.005

Li XD, Zhan JX, Chen J, Huang RC. Clinical effect study of aripiprazole combined with lithium carbonate on bipolar affective disorder comorbidity non-suicidal self-injury (in Chinese). Med Innov China. 2023;20:43–7. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-4985.2023.21.010

Xu YC, Kong FZ, Zhuang Y, Liu LL. Application of narrative nursing in a case of adolescent depression accompanied by non-suicidal self-injury (in Chinese). Chin Evidence-based Nurs. 2023;9:2196–9. https://doi.org/10.12102/j.issn.2095-8668.2023.12.019

Zhang TH, Zhu JJ, Wang JJ, Tang YY, Xu LH, Tang XC, et al. An open-label trial of adjuvant high-frequency left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for treating suicidal ideation in adolescents and adults with depression. J ect. 2021;37:140–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/yct.0000000000000739

Chen L, Li YY, Li SP. Effect of phased intervention to improve non⁃suicidal self⁃injury behavior in adolescents with depression (in Chinese). Chin Nurs Res. 2023;37:2794–9. https://doi.org/10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2023.15.022

Pan F, Li D, Wang X, Lu S, Xu Y, Huang M. Neuronavigation-guided high-dose repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for the treatment of depressive adolescents with suicidal ideation: a case series. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2018;14:2675–9. https://doi.org/10.2147/ndt.S176125

Cai H, Du R, Song J, Wang Z, Wang X, Yu Y, et al. Suicidal ideation and electroconvulsive therapy: outcomes in adolescents with major depressive disorder. J ect. 2023;39:166–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/yct.0000000000000906

Ye CL, Zhou YZ, Zeng B. Clinical efficacy of sodium valproate sustained-release tablets combined with low-dose quetiapine in the treatment of adolescent depression patients with non-suicidal self injury and its impact on serum thyroid hormones (in Chinese). Women’s Health. 2023;45-6.

Dai LQ, Zhang XL, Yu RQ, Wang XY, Deng F, Li X, et al. Abnormal brain spontaneous activity in major depressive disorder adolescents with non-suicidal self injury and its changes after sertraline therapy. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1177227. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1177227

Li SM, Cai R, Feng JY, Liang J, Mai LH. Efficacy and safety of fluoxetine combined with olanzapine in the treatment of adolescents with depressive disorder complicated with self-injury suicidal behavior (in Chinese). Chin Foreign Med Res. 2021;19:14–6. https://doi.org/10.14033/j.cnki.cfmr.2021.20.005

Lin XZ. Efficacy study dialectical behavior therapy for adolescent depression with non-suicidal self-injury (in Chinese). Chongqing Medical University. Chongqing. 2021.

Peng HZ. A Preliminary Study on the Efficacy of Simplified Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in Adolescent Depressive Patients with Non-suicidal Self-injury (in Chinese). Shanxi Medical University. Shanxi. 2021.

Shao HH. Objective to study the clinical effect of cognitive correction and behavior shaping nursing mode on adolescent depression patients with suicidal tendency (in Chinese). Health Sci. 2021;24:69–70. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-9714.2021.09.069

Wang YP, Liang JQ, Pan JH, Wang XN, Chen JX. Application of group psychological intervention in adolescent patients with depression and non-suicidal self injury (in Chinese). Dang Dai Hu Shi. 2022;29:121–6. https://doi.org/10.19793/j.cnki.1006-6411.2022.18.036

Yuan GC, Zheng YL, Tang RQ. Efficacy of escitalopram tablets combined with behavioral cognitive therapy on non-suicidal selfinjury behavior in depressive adolescents (in Chinese). Smart Healthc. 2022;8:124–6. https://doi.org/10.19335/j.cnki.2096-1219.2022.11.038

Lu HL, Liu Y, Huang ZW, Guo M, Huang XQ, Xu Q, et al. Development and application effect of knowledge-to-action framework-based health management in adolescents with depressive disorder in remote counties (in Chinese). Chin Gen Pract. 2022;25:1373–7. https://doi.org/10.12114/j.issn.1007-9572.2021.01.417

Feng YX. Effect of group dialectical behavior therapy on adolescent depression with suicidal ideation (in Chinese). Chongqing Medical University. Chongqing. 2022.

Ding HQ, Yang F, He XJ. Effect of emotional regulation strategy on non-suicidal self-injury behavior of adolescents with depressive disorder (in Chinese). J Nurs Sci. 2021;36:62–5. https://doi.org/10.3870/j.issn.1001-4152.2021.08.062

Yu H, Long SS, Zhou Y. A clinical study of low frequency rTMS stimulation in the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex (VMPFC) combined with Sertraline on the treatment of the adolescents with non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors (in Chinese). Int J Psychiatry. 2021;48:987–90,93.

Zhang JY, Xia Y, Shi XM, Xu Y. Clinical efficacy of sodium valproate sustained -release tablets combined with low -dose quetiapine in the treatment of adolescent depression with non -suicide self-injury and its effect on serum thyroid hormone (in Chinese). J Clin Exp Med. 2022;21:2300–3. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-4695.2022.21.016

Duan S, Wang H, Wilson A, Qiu J, Chen G, He Y, et al. Developing a text messaging intervention to reduce deliberate self-harm in Chinese adolescents: Qualitative study. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020;8:e16963. https://doi.org/10.2196/16963

Tang TC, Jou SH, Ko CH, Huang SY, Yen CF. Randomized study of school-based intensive interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed adolescents with suicidal risk and parasuicide behaviors. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:463–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01991.x

Hu ZZ. A Comparative study of acceptance and commitment therapy and dialectical behavior therapy on adolescent non-suicidal self-injury (in Chinese). Nanchang University. Jiangxi. 2022.

Wang CL, Zhu KM, Lin XY, Liu ZC, Gu DH, Wang D. A research on cognitive adjustment and behavioral shaping model of adolescent depression patients with suicide idea (in Chinese). World Latest Med Inf. 2013;13:29–30. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1671-3141.2013.21.016

Liang QL, Tan YK, Liang JQ, Zhang ZD, Pan JH, Liao QX. The effect of positive psychological intervention on adolescents with depressive disorder and non-suicidal self-harm (in Chinese). Chin Clin Nurs. 2022;14:94–97. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1674-3768.2022.02.007

Zhu YZ, Shu JP, Chen G, He J. The effect of bilateral sequential repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation combined with medication on non suicidal self injury in adolescent depression patients (in Chinese). Da Yi Sheng. 2022;7:59–61.

Su M. Clinical characteristics and nursing strategies of adolescent depression patients with suicidal tendencies (in Chinese). Advice For Health. 2022;16:139–41.

Qiu HJ. The clinical efficacy of sensory integration therapy on adolescent depression (in Chinese). Clin Res. 2022;30:43–6. https://doi.org/10.12385/j.issn.2096-1278(2022)05-0043-04

Li YS. The clinical effect of the first treatment of adolescent depression disorder patients with self-injury acts in acute period of drug combination (in Chinese). Hebei Medical University. Hebei. 2022.

Zeng QL. Research on effect of combined MECT in depressive disorder adolescent with non-suicidal self-injury in the acute phase treatment (in Chinese). Chongqing Medical University. Chongqing. 2022.

Cai XF, Pan JH, Liang JQ. The effect of parent-child group combined with psychological counseling on the depressive mood of adolescent patients with depressive episodes and self injurious behavior (in Chinese). Jia You Yun Bao. 2021;3:213.

Quan LJ, Zhao Y, Ying DX. Clinical effect of sensory integration therapy on adolescent depression (in Chinese). Chin J Rehabilitation Med. 2020;35:551–5. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1001-1242.2020.05.008

Li HZ. Efficacy study of DBT individual therapy on depressive adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury (in Chinese). Chongqing Medical University. Chongqing. 2022.

Wu J, Qin Z, Li SJ. Clinical observation of quetiapine combined with sertraline in the treatment of adolescent depression with non suicidal self injury behavior (in Chinese). World Healthy Living. 2022;16:104–7.

He AN, Xiong ZF, Cheng YR, Li SJ, Xu Q. A Case study on the evaluation of self injurious behavioral function in children with autism and the intervention of integrating medicine and education (in Chinese). J Suihua Univ. 2018;38:85–90.

Xue ZF, Zhang YD, Lu QZ, Zhang WJ. A Comparative study of dialectical behavior therapy in the treatment of adolescent depression with non suicidal self injury (in Chinese). Psychologies. 2022;17:48–50. https://doi.org/10.19738/j.cnki.psy.2022.08.016

Zhu P, Zhu F, Ji CF, Kong FZ, Du X, Ji F, et al. Application of williams life skills training in depressive adolescents with non-suicidal self-injury (in Chinese). Sichuan Ment Health. 2021;34:131–4. https://doi.org/10.11886/scjsws20201031001

Lin G. Analysis of the nursing effect of parent-child group combined with psychological counseling on adolescent depression accompanied by self-injury behavior (in Chinese). J Front Med. 2022;12:104–6.

Zou YR. Daily behavior characteristic of autism teenagers and intervention methods (in Chinese). Chin J Sch Health. 2016;37:1308–10. https://doi.org/10.16835/j.cnki.1000-9817.2016.09.008

Li LJ, Ma X. Interpretation of the Chinese guidelines for the prevention and treatment of depression (Second Edition): overview (in Chinese). Chin J Psychiatry. 2017;50:167–8. https://doi.org/10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-7884.2017.03.002

Xiang Y-T, Li W, Zhang Q, Jin Y, Rao W-W, Zeng L-N, et al. Timely research papers about COVID-19 in China. Lancet. 2020;395:684–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30375-5

Nutt DJ, Goodwin GM, Bhugra D, Fazel S, Lawrie S. Attacks on antidepressants: signs of deep-seated stigma? Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:102–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70232-9

Schreiber MA, Wiese M. Black-box warnings: how they can improve your clinical practice. Curr Psychiatry. 2019;18:18–26.

Xiao Y, Chen TT, Liu L, Zong L. China ends its zero-COVID-19 policy: new challenges facing mental health services. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;82:103485. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajp.2023.103485

Benson NM, Seiner SJ. Electroconvulsive therapy in children and adolescents: clinical indications and special considerations. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2019;27:354–8. https://doi.org/10.1097/hrp.0000000000000236

Jasbi M, Sadeghi Bahmani D, Karami G, Omidbeygi M, Peyravi M, Panahi A, et al. Influence of adjuvant mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) on symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in veterans - results from a Randomized Control study. Cogn Behav Ther. 2018;47:431–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2018.1445773

Zhang XJ, Lin J, Feng L, Ou M, Gong FQ. Non-pharmacological interventions for patients with psoriasis: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e074752. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-074752

Mészáros Crow E, López-Gigosos R, Mariscal-López E, Agredano-Sanchez M, García-Casares N, Mariscal A, et al. Psychosocial interventions reduce cortisol in breast cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychol. 2023;14:1148805. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1148805

Hetrick SE, Purcell R, Garner B, Parslow R. Combined pharmacotherapy and psychological therapies for post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;7:Cd007316. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD007316.pub2

Jeong H, Yim HW, Lee SY, Potenza MN, Kim NJ. Effectiveness of psychotherapy on prevention of suicidal re-attempts in psychiatric emergencies: a systematic review and network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Psychother Psychosom. 2023;92:152–61. https://doi.org/10.1159/000529753

Iyengar U, Snowden N, Asarnow JR, Moran P, Tranah T, Ougrin D. A further look at therapeutic interventions for suicide attempts and self-harm in adolescents: an updated systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:583. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00583