Abstract

Dendrimers are synthetic polymers with well-defined structures and drug-loading capacity and are useful as nanocarriers for drug delivery systems. Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers modified with phenylalanine (Phe) showed pH- and temperature-sensitive properties, the sensitivities of which were controlled by the terminal groups. Anionic-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers showed upper critical solution temperature (UCST)-type thermosensitive properties at acidic pH. Some of them showed both lower critical solution temperature (LCST)- and UCST-type thermosensitive behaviors, which were switched by pH. Anionic-terminal dendrimers, including Phe-modified dendrimers, accumulated in the lymph nodes after intradermal injection at the foot pads. Carboxy-terminal hydrophobic dendrimers modified with cyclohexanedicarboxylic acid (CHex) and Phe, such as PAMAM-CHex-Phe, were associated with lymph node-resident immune cells, including T cells. Because of the stimuli sensitivity, the association of PAMAM-CHex-Phe with T cells was enhanced at pH 6.5. These dendrimers were applied to the delivery of model drugs and nucleic acids into T cells. Because T cells in lymph nodes are important for cancer immunotherapy, anionic-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers with the ability to deliver bioactive molecules into T cells are useful for applications in cancer immunotherapy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nanomedicine is a medical application of nanotechnology that includes drug delivery systems and diagnosis. There are many nanomaterials for biomedical applications, including liposomes, micelles, polymers, and metal nanoparticles [1,2,3,4,5]. Because the size and surface properties of nanoparticles significantly influence their biodistribution, researchers have designed and prepared various types of nanoparticles [3,4,5]. Polymers are often used in nanomedicine because their composition, chain length, and architecture can be adjusted to tune nanoparticle properties [3,4,5]. Synthetic polymers generally exhibit polydisperse molecular weights and irregular conformations, which distinguish them from naturally occurring proteins. Dendrimers with tree-like structures, first reported by Tomalia et al. in 1985, are a class of synthetic polymers characterized by highly branched and well-defined structures with uniform molecular weights because they are produced through a stepwise organic synthesis process [5,6,7,8,9]. Each reaction cycle is related to generation (G), with the molecular weight and number of terminal groups controlled accordingly. The number of terminal groups generally doubles with each generation, and their molecular weight increases in a stepwise manner. Dendrimer properties can be tuned by altering their inner core structure, building blocks, and/or terminal groups. Their monodispersed molecular weights and defined chemical structures contribute to high chemical and biological reproducibility [5,6,7,8,9]. Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers have been widely studied and are commercially available. The dendrimer is synthesized by repeated reaction cycles using methyl acrylate and ethylenediamine, initiated from a core diamine compound. The diameters of the dendrimers range from 2.2 to 13.5 nm, depending on the generation. The sizes of insulin, cytochrome c, and hemoglobin are approximately 3.0, 4.5, and 5.5 nm, corresponding roughly to G3, G4, and G5 dendrimers, respectively [7, 8]. In addition to PAMAM, various other types of dendrimers have been synthesized, including poly(propylene imine) (PPI), polyester, and poly L-lysine dendrimers. Clinical studies using poly L-lysine dendrimers as drug carriers are currently being conducted by Starpharma (Australia) [9,10,11]. Dendri-graft polylysines, which are alternatives to poly-L-lysine dendrimers, are also commercially available [12]. Dendrimers possess numerous terminal functional groups and an internal space suitable for the conjugation and encapsulation of bioactive and functional molecules, respectively [8,9,10,11,12,13]. In some cases, dendrimer modification extends beyond simple conjugation. Attached moieties can exhibit clustering effects because of their high terminal densities. For example, the binding affinities of sugar- and peptide-modified dendrimers are significantly greater than those of the corresponding original molecules because of the clustering effect [11]. Peptides linked to the surface of the dendrimers can also induce higher-order structures [11, 13]. Therefore, dendrimers are potent functional nanomaterials in the biomedical field. Numerous review articles have been published on the biomedical applications of dendric polymers [6, 8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. Recently, we showed that dendrimers conjugating phenylalanine (Phe), a hydrophobic amino acid, at their termini exhibit unique stimuli sensitivity and the ability to be delivered into lymph nodes and immune cells, including T cells. This review focuses on their stimuli-responsive properties and applications in delivery systems for lymph node-resident immune cells.

Synthesis and stimuli-responsive properties of anionic-terminal phenylalanine-modified dendrimers

Temperature-responsive polymers are smart materials that are classified into lower critical solution temperature (LCST) types, which become turbid upon heating, and upper critical solution temperature (UCST) types, which dissolve upon heating. Poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (poly(NIPAM)) is a representative example of an LCST-type thermoresponsive polymer, and polymers with zwitterionic structures exhibit UCST-type thermoresponsiveness [16]. Temperature-responsive dendrimers have been studied using thermoresponsive polymers and hydrophobic compounds [14, 15]. The N-isopropyl amide group, a side chain of poly(NIPAM), was introduced into the dendrimer termini, enabling the creation of temperature-responsive dendrimers. Although the dehydration of water molecules bound to poly(NIPAM) chains is known to drive the response in temperature-responsive polymers, no significant endothermic dehydration was observed near the phase transition temperature in N-isopropyl amide-terminal dendrimers [15]. The phase transition temperature of the temperature-responsive dendrimer was changed by varying the compound attached to its terminal end. Because dendrimers can encapsulate certain materials, the phase transition temperature is also affected by the materials encapsulated in the dendrimer [14, 15]. Thermoresponsive dendrimers were also synthesized by attaching elastin- and collagen-like peptides, as these peptides change their conformation upon heating [13, 15]. Natural compounds are better suited than synthetic compounds for designing nanoparticles for biomedical applications.

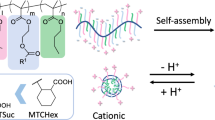

Phenylalanine (Phe) is an essential amino acid with a phenyl group on its side chain. Phe can enter cells via L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) and, the aggregates interact directly with the cell membrane [17, 18]. Amino-terminal Phe-modified PAMAM dendrimers have been produced for gene delivery and have shown efficient transfection activity [19]. Notably, the sensitivity of Phe-modified PAMAM dendrimers to changes in both pH and temperature depends on the structure of the terminal group [20,21,22] (Fig. 1). Amino-terminal Phe-modified PAMAM dendrimers exhibit LCST-type temperature responsiveness under neutral pH conditions (Fig. 2) [20]. In contrast, carboxy-terminal Phe-modified PAMAM dendrimers exhibit UCST-type temperature responsiveness under acidic conditions [21, 22]. In these studies, carboxy-terminal Phe-modified PAMAM dendrimers were produced by reaction with acid anhydrides such as succinic anhydride (Suc) and Phe. Two types of dendrimers were synthesized by varying the reaction order. The PAMAM dendrimer that reacted with Suc and Phe in the order, PAMAM-Suc-Phe, exhibited UCST-type temperature responsiveness at pH 5 [21]. In contrast, the PAMAM dendrimer that reacted with Phe and Suc in the order, PAMAM-Phe-Suc, exhibited UCST-type temperature responsiveness at pH 5.5, and the temperature responsiveness converted to LCST-type at pH 4 (Fig. 3) [22]. The temperature responsiveness of the UCST-type has been reported to arise from electrostatic interactions owing to the zwitterionic structures within the polymer chains or the hydrogen bonding of the carboxy groups [16, 23]. Carboxy-terminal PAMAM dendrimers are zwitterionic polymers with anions at their termini and cations at their internal branches. The ionic states of these groups change at different pH values, as does the temperature responsiveness. When PAMAM-Phe-Suc was quaternized, the temperature responsiveness disappeared under all the tested pH conditions [22], suggesting that the tertiary amino group in the dendrimer is crucial for temperature and pH responsiveness. The ζ-potentials of PAMAM-Phe-Suc and PAMAM-Suc-Phe were measured at different pH values. Both exhibited negative ζ-potentials at basic pH, which increased as the pH decreased. PAMAM-Phe-Suc became nearly neutral at pH 5, under which it showed UCST-type temperature responsiveness. PAMAM-Phe-Suc exhibited slightly negative and positive ζ-potentials at pH 5.5 and 4 [22], under which it showed UCST- and LCST-type temperature responsiveness, respectively (Fig. 3). Because the ternary amines in the dendrimer are protonated at pH 5-5.5, zwitterionic structures are formed to induce UCST-type temperature responsiveness. Most of the terminal carboxylic acids and ternary amines in the dendrimer were protonated at pH 4, resulting in a positively charged surface. The pKa of the dendrimer was measured at different temperatures. Because the pKa at 50 °C was lower than that at 20 °C, the fraction of deprotonated carboxylic acid was increased by heating at pH 4 [22]. This deprotonation led to a neutral surface charge, making the dendrimer more hydrophobic and thus inducing the LCST-type temperature responsiveness. The structures of acid anhydrides and the number of bound Phe molecules could also influence temperature and pH sensitivity [21, 24, 25]. Cyclohexanedicarboxylic anhydride (CHex) was used instead of Suc. PAMAM-CHex-Phe and PAMAM-Phe-CHex were synthesized and showed UCST-type temperature-sensitive properties at pH 6.5 and 7, respectively [21, 24]. Because the increased hydrophobicity increases the pKa of the carboxylic acid in the dendrimers, the zwitterionic structure possibly forms at high pH. A sulfonate-terminal Phe-modified dendrimer (PAMAM-Phe-SO3Na) was synthesized by converting a terminal carboxy group into a sulfonate group. This dendrimer also exhibited UCST- and LCST-type temperature responsiveness at pH 6.5 and pH 5, respectively. Compared with PAMAM-Phe-Suc, PAMAM-Phe-SO3Na exhibited more sensitive phase transition behavior (Fig. 3) [22]. This may be because PAMAM-Phe-SO3Na forms a more stable zwitterionic structure at adjacent sites. The number of bound Phe molecules also influences temperature and pH sensitivity [24]. Thus, stimuli sensitivity can be tuned by the dendrimer structure.

Thermosensitivity of amino-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers at different pH values. Reprinted (adapted) with permission from [20]. Copyright 2006 American Chemical Society

Thermosensitivity of A PAMAM-Suc-Phe, B PAMAM-Phe-Suc and C PAMAM-Phe-SO3Na at different pH values [22]. The lines at pH 6 and 3.5 overlap in Panel B, and those at pH 7 and 4 overlap in Panel C

Some anionic-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers have been used to separate organic molecules from aqueous solutions, the separation efficiency of which depends on temperature and pH [21, 22]. These dendrimers have also been used as nanocontainers of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs). AuNPs have unique optical properties because of their surface plasmon resonance. A colorimetric sensor responsive to the dual stimuli of pH and temperature was designed and prepared by loading AuNPs onto PAMAM-Phe-Suc. The solution color changed when the pH was less than 5 and when the temperature increased above 50 °C simultaneously. In contrast, no spectral changes were observed upon heating at pH 5.5. The color change was irreversible, making it useful as a colorimetric sensor for recording thermal history under acidic pH conditions [26]. AuNPs are also useful catalysts. The stimuli-responsive dendrimers loaded with AuNPs showed peroxidase-like activity, which was affected by the solution pH and temperature. The dispersion stability of the AuNPs and the surface area of the AuNPs are important for catalytic activity. Because the AuNPs loaded into the dendrimers were stably dispersed without binding to any ligands, the enzymatic activity was relatively stable. Thus, AuNP-loaded dendrimers are useful as nanozymes [27].

Applications for delivery into lymph node-resident immune cells

Lymph nodes are the storehouses of many types of immune cells, such as T cells, B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages, which are involved in various immune responses. Lymph nodes are important in cancer diagnosis and therapy because metastatic cancer cells often migrate to the lymph nodes surrounding the primary tumor tissue [28]. Immune cells in the lymph nodes near tumors play a crucial role in cancer immunotherapy. Although immunotherapy can induce long-term antitumor activity, the low response rate is a major problem [29]. The efficacy of cancer immunotherapy can be enhanced by establishing a delivery system that targets immune cells in the lymph nodes. Dendrimers with small particle sizes of less than 70 kDa are advantageous for delivery to lymph node-resident immune cells, as large nanoparticles cannot diffuse through densely packed B- and T-cell zones in the lymph nodes [30]. To develop suitable dendrimers, we first optimized the dendrimer structure for lymph node delivery by adjusting the particle size and surface charge. PAMAM dendrimers G2, G4, G6, and G8, bearing cationic-amino, anionic-carboxy, or nonionic-acetyl groups at their termini, were synthesized, and some chelating compounds were conjugated. After radiolabeling with 111In ions, the dendrimers were intradermally injected into foot pads, and their biodistribution was examined (Fig. 4). All the G2 dendrimers migrated to the kidneys, regardless of the terminal functional group. The biodistribution of the dendrimers of G4 and higher generations differed depending on the terminal group. The amino-terminal dendrimers largely remained at the injection site. The acetyl-terminal G8 and G6 dendrimers were observed in the blood. The carboxyl-terminal dendrimers accumulated in the lymph nodes, liver and spleen. These results indicated that anionic carboxy-terminal dendrimers of G4 and higher generations are useful for delivery to lymph nodes and for lymph node imaging [31].

Biodistribution of various dendrimers after intradermal injection. Reprinted from [31], Copyright (2015), with permission from Elsevier

Next, different dendrimers with anionic termini, such as carboxylate, sulfonate, and phosphate, were synthesized, and their biodistributions were compared after intradermal injection into foot pads [32]. Carboxy-terminal dendrimers produced by the reaction of succinic anhydrate, PAMAM-Suc, have already been studied. Another carboxy-terminal dendrimer, PAMAM-CHex-Phe, was synthesized by reacting hydrophobic CHex and Phe [33]. All anionic-terminal dendrimers accumulated in the lymph nodes; however, their interactions with immune cells in the lymph nodes differed depending on the terminal structure. Phosphate-terminal dendrimers were internalized by B cells, dendritic cells, and macrophages, whereas sulfonate-terminal dendrimers were rarely internalized by immune cells [32]. The association of carboxy-terminal dendrimers with lymph node-resident immune cells differed; PAMAM-CHex-Phe was associated with immune cells, including CD3-positive T cells, but PAMAM-Suc was not (Fig. 5) [33]. These results suggest that controlling the anionic-terminal groups of dendrimers can alter their cell-association properties in lymph nodes.

Flow cytometry of PE-CD3-stained lymph node-resident T cells collected from the lymph nodes of mice injected with green fluorescent dye (HF488)-conjugated dendrimers [33]. C-den and CPhe-den indicate PAMAM-Suc and PAMAM-CHex-Phe, respectively

In cancer immunotherapy, killer T cells, which are educated in the lymph nodes near the tumor, migrate to the tumor and attack cancer cells [28, 29]. Therefore, a delivery system for the T cells present in lymph nodes near the tumor is needed. However, unlike delivery to phagocytic cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells, delivery to T cells is challenging. To date, antibodies targeting cell surface-localized receptors have been used in cancer immunotherapy [29]. As PAMAM-CHex-Phe is associated with T cells in lymph nodes, cellular uptake into T cells was examined in detail at various temperatures. PAMAM-CHex-Phe interacted with T cells at 37 °C, whereas essentially no uptake was observed at 4 °C (Fig. 6A). A dendrimer labeled with a fluorescent dye was observed near the cell nuclei using confocal microscopy, indicating that the dendrimer was internalized into T cells [34]. Like PAMAM-CHex-Phe, PAMAM-Phe-CHex also exhibited T-cell internalization properties (Fig. 6B) [34]. As described in the previous section, PAMAM-CHex-Phe and PAMAM-Phe-Chex exhibit stimuli-responsive properties [21, 24]. The interaction of these dendrimers with T cells was significantly enhanced at pH 6.5 (Fig. 6), which is the pH observed in the tumor microenvironment (TME), suggesting their usefulness for delivery into T cells in the TME. Dendrimers with leucine (Leu) substituted for Phe were also synthesized, and their interactions with T cells were examined. No effective uptake of the anionic-terminal Leu-modified dendrimers by T cells was observed, suggesting that Phe is crucial for uptake by T cells [34]. Phe forms aggregates at high concentrations and is internalized by cells in patients with phenylketonuria [18]. Clustering of Phe at the dendrimer periphery may be important for its internalization into T cells. Therefore, carboxy-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers are useful for delivery into T cells in lymph nodes. Since the number of bound Phe molecules, the linker structure between Phe and the dendrimer, and the core dendrimer structure in anionic-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers also affect their association with T cells [35,36,37], optimization of the dendrimer structure is necessary for efficient delivery to T cells.

Carboxy-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers were applied to deliver model drug molecules. Paclitaxel (PTX) is a typical hydrophobic anticancer drug with immune-modulating effects [38] and hence was loaded into carboxy-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers. The loading capacity is also affected by the dendrimer structure, such as the number of bound Phe molecules and the linker and core structures [36, 37]. CHex and Phe-conjugated dendri-graft polylysine of G3 was found to be the most useful for the delivery of PTX into T cells in our study [37]. PAMAM-CHex-Phe has also been used for gene delivery into T cells. First, binary complexes were prepared using plasmid DNA and Lipofectamine, a cationic lipid-based transfection agent. The surfaces of the binary complexes were then coated with PAMAM-CHex-Phe to enhance T-cell uptake. The transfection activity of the ternary complexes containing PAMAM-CHex-Phe was greater than those of the binary and ternary complexes containing PAMAM-Suc, suggesting a positive effect of PAMAM-CHex-Phe [39].

Although anionic-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers efficiently internalized T cells, their selective delivery into T cells is currently problematic. T cells are classified into various subsets, such as killer T cells (CD3 + CD8 + ) and helper T cells (CD3 + CD4 + ), with different functions. Our dendrimers were internalized by both types of T cells in addition to various types of immune cells in lymph nodes [34]. The addition of ligands to dendrimers is a possible solution to achieve dendrimer cell selectivity. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T-cell therapy is a type of cell-based cancer immunotherapy in which CARs are genetically engineered to be expressed on the surface of a patient’s T cells. The transfection of CAR genes into T cells is indispensable for CAR-T-cell therapy. Because T cells are selectively collected before transfection, cell selectivity is not necessary [40]. Thus, the dendrimers that we developed would be used for CAR-T-cell production.

Conclusions

This review summarizes the stimuli-sensitive properties of anionic-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers and their biomedical applications. Anionic-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers exhibit UCST-type thermosensitivity under weakly acidic conditions, the sensitivity of which is altered by the dendrimer structure. PAMAM-Phe-Suc and PAMAM-Phe-SO3Na exhibit pH-switchable LCST/UCST thermosensitivity. Anionic-terminal dendrimers are valuable for delivery to lymph nodes through intradermal administration at food pads due to their small size. Cellular interactions after migration from the injection site to the lymph nodes differ depending on the dendrimer terminal structure. The hydrophobic PAMAM-CHex-Phe interacts with immune cells, including T cells, whereas hydrophilic PAMAM-Suc does not. The clustering effect of Phe on the dendrimer surface may be important for cell association. T cells play central roles in various immunoreactions. Thus, anionic-terminal Phe-modified dendrimers show promise for delivery into T cells for immunotherapy.

References

Shi J, Kantoff PW, Wooster R, Farokhzad OC. Cancer nanomedicine: progress, challenges and opportunities. Nat Rev Cancer. 2017;17:20–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc.2016.108.

Halwani AA. Development of pharmaceutical nanomedicines: From the bench to the market. Pharmaceutics. 2022;14:106. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics14010106.

Liu Q, Zou J, Chen S, He W, Wu W. Current research trends of nanomedicines. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2023;13:4391–416. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apsb.2023.05.018.

Duncan R, Vicent MJ. Polymer therapeutics-prospects for 21st century: The end of the beginning. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2023;65:60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2012.08.012.

Khandare J, Calderón M, Dagia NM, Haag R. Multifunctional dendritic polymers in nanomedicine: opportunities and challenges. Chem Soc Rev. 2012;41:2824–48. https://doi.org/10.1039/C1CS15242D.

Tomalia DA, Baker H, Dewald J, Hall M, Kallos G, Martin S, et al. A new class of polymers: Starburst-dendritic macromolecules. Polym J. 1985;17:117–32. https://doi.org/10.1295/polymj.17.117.

Tomalia DA, Naylor AM, Goddard WA. Starburst dendrimers: Molecular-level control of size, shape, surface chemistry, topology, and flexibility from atoms to macroscopic matter. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1990;29:138–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/anie.199001381.

Svenson S, Tomalia DA. Dendrimers in biomedical applications - reflections on the field. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2005;57:2106–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2005.09.018.

Lee CC, MacKay JA, Fréchet JMJ, Szoka FC. Designing dendrimers for biological applications. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:1517–26. https://doi.org/10.1038/nbt1171.

Dias AP, da Silva Santos S, da Silva JV, Parise-Filho R, Igne Ferreira E, Seoud OE, et al. Dendrimers in the context of nanomedicine. Int J Pharm. 2020;573:118814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.118814.

Astruc D, Boisselier E, Ornelas C. Dendrimers designed for functions: From physical, photophysical, and supramolecular properties to applications in sensing, catalysis, molecular electronics, photonics, and nanomedicine. Chem Rev. 2010;110:1857–959. https://doi.org/10.1021/cr900327d.

Francoia JP, Vial L. Everything you always wanted to know about poly-l-lysine dendrigrafts (But were afraid to ask). Chem Eur J. 2018;24:2806–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201704147.

Kojima C. Design of biomimetic interfaces at the dendrimer periphery and their applications (Chapter 12), In: Kawai T, Hashizume M, editors. Stimuli-responsive interfaces. Fabrication and application. Springer; 2016. p209–227.

Kono K. Dendrimer-based bionanomaterials produced by surface modification, assembly and hybrid formation. Polym J. 2012;44:531–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/pj.2012.39.

Kojima C. Design of stimuli-responsive dendrimers. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2010;7:307–19. https://doi.org/10.1517/17425240903530651.

Bordat A, Boissenot T, Nicolas J, Tsapis N. Thermoresponsive polymer nanocarriers for biomedical applications. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2019;138:167–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2018.10.005.

Puris E, Gynther M, Auriola S, Huttunen KM. L-Type amino acid transporter 1 as a target for drug delivery. Pharm Res. 2020;37:88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11095-020-02826-8.

Perkins R, Vaida V. Phenylalanine increases membrane permeability. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:14388–91. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.7b09219.

Kono K, Akiyama H, Takahashi T, Takagishi T, Harada A. Transfection activity of polyamidoamine dendrimers having hydrophobic amino acid residues in the periphery. Bioconj. Chem. 2005;16:208–14. https://doi.org/10.1021/bc049785e.

Tono Y, Kojima C, Haba Y, Takahashi T, Harada A, Yagi S, et al. Thermosensitive properties of poly(amidoamine) dendrimers with peripheral phenylalanine residues. Langmuir. 2006;22:4920–2. https://doi.org/10.1021/la060066t.

Tamaki M, Fukushima D, Kojima C. Dual pH-sensitive and UCST-type thermosensitive dendrimers: Phenylalanine-modified polyamidoamine dendrimers with carboxyl termini. RSC Adv. 2018;8:28147. https://doi.org/10.1039/C8RA05381B.

Tamaki M, Kojima C. pH-Switchable LCST/UCST-type thermosensitive behaviors of phenylalanine-modified zwitterionic dendrimers. RSC Adv. 2020;10:10452. https://doi.org/10.1039/D0RA00499E.

Niskanen J, Tenhu H. How to manipulate the upper critical solution temperature (UCST)?. Polym Chem. 2017;8:220–32. https://doi.org/10.1039/C6PY01612J.

Kojima C, Fu Y, Tamaki M. Control of stimuli sensitivity in pH-switchable LCST/UCST-type thermosensitive dendrimers by changing the dendrimer structure. Polymers. 2022;14:2426. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym14122426.

Shiba H, Matsumoto A, Kojima C. LCST/UCST-type thermosensitive properties of carboxy-terminal PAMAM dendrimers modified with different numbers of phenylalanine residues. Polym J. 2025;57:137–42. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-024-00963-0.

Kojima C, Xia H, Yamamoto Y, Shiigi H. A naked-eye colorimetric pH and temperature sensor based on gold nanoparticle-loaded stimuli-sensitive dendrimers. ChemNanoMat. 2022;8:e202100442. https://doi.org/10.1002/cnma.202100442.

Kojima C, Xia H. Gold nanoparticle-loaded stimuli-sensitive dendrimers with peroxidase-like activity for cancer treatment. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2025;8:9101–8. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsanm.5c01945.

Trevaskis NL, Kaminskas LM, Porter CJH. From sewer to saviour — Targeting the lymphatic system to promote drug exposure and activity. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2015;14:781–803. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrd4608.

Nam J, Son S, Park KS, Zou W, Shea LD, Moon JJ. Cancer nanomedicine for combination cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Mater. 2019;4:398–414. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41578-019-0108-1.

Swartz MA, Lund AW. Lymphatic and interstitial flow in the tumour microenvironment: linking mechanobiology with immunity. Nature Rev Cancer. 2012;12:210–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc3186.

Niki Y, Ogawa M, Makiura R, Magata Y, Kojima C. Optimization of dendrimer structure for sentinel lymph node imaging: Effects of generation and terminal group. Nanomed NBM. 2015;11:2119–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nano.2015.08.002.

Nishimoto Y, Nagashima S, Nakajima K, Ohira T, Sato T, Izawa T, et al. Carboxyl-, sulfonyl-, and phosphate-terminal dendrimers as a nanoplatform with lymph node targeting. Int J Pharm. 2020;576:119021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119021.

Nishimoto Y, Nishio M, Nagashima S, Nakajima K, Ohira T, Nakai S, et al. Association of hydrophobic carboxyl-terminal dendrimers with lymph node-resident lymphocytes. Polymers. 2020;12:1474. https://doi.org/10.3390/polym12071474.

Shiba H, Nishio M, Sawada M, Tamaki M, Michigami M, Nakai S, et al. Carboxy-terminal dendrimers with phenylalanine for pH-sensitive delivery system into immune cells including T cells. J Mater Chem B. 2022;10:2463–70. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1TB01980E.

Shiba H, Hirose T, Fu Y, Michigami M, Fujii I, Nakase I, et al. T cell-association of carboxy-terminal dendrimers with different bound numbers of phenylalanine and their application to drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2023;15:888. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15030888.

Shiba H, Hirose T, Sakai A, Nakase I, Matsumoto A, Kojima C. Structural optimization of carboxy-terminal phenylalanine-modified dendrimers for T-cell association and model drug loading. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16:715. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics16060715.

Kojima C, Sakai A, Kadonosono T Hydrophobic drug delivery into T Cells using carboxy-terminal phenylalanine-modified dendrigraft polylysines. Macromol Biosci. 2025;e00207 (in press). https://doi.org/10.1002/mabi.202500207.

Manspeaker MP, Thomas SN. Lymphatic immunomodulation using engineered drug delivery systems for cancer immunotherapy. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2020;160:19–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2020.10.004.

Kojima C, Sawada M, Nakase I, Matsumoto A. Gene delivery into T-Cells using ternary complexes of DNA, Lipofectamine, and carboxy-terminal phenylalanine-modified dendrimers. Macromol Biosci. 2023;23:2300139. https://doi.org/10.1002/mabi.202300139.

Wang M, Yu F, Zhang Y. Present and future of cancer nano-immunotherapy: opportunities, obstacles and challenges. Mol Cancer. 2025;24:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-024-02214-5.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) Grants JP22H04556 and JP20H05232 (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Area: Aquatic Functional Materials), the Izumi Science and Technology Foundation, the Asahi Glass Foundation, and the “Innovation inspired by Nature” Research Support Program, SEKISUI CHEMICAL CO., LTD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kojima, C. Biomedical applications of anionic-terminal phenylalanine-modified dendrimers with unique stimuli-responsive behaviors. Polym J (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01115-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41428-025-01115-8