Abstract

Background

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is an avoidable cause of childhood blindness. Effective ROP screening enables the detection of cases requiring treatment, but the frequency of ROP varies in units across South Africa (SA). Recent evidence suggests that a high proportion of infants in SA do not complete screening. A comparison of ROP prevalence and completeness of screening in units within the same region has yet to be described.

Methods

A prospective study of infants screened for ROP at five units was conducted between 1 February 2023 and 30 April 2024 in Cape Town, SA. Data were extracted for infants with birth weight <1250 grams or gestational age <32 weeks from the Retinopathy of Prematurity South African (ROPSA) register.

Results

Screening was initiated in 933 infants and completed in 468 (50.2%). Completeness of screening varied in the units from 36.8% to 74.6%. The prevalence of ROP among infants who started screening (16.1%–71.2%), completed screening (13.1%–64.3%), and those incompletely screened (25.0%–79.2%) also varied in the units. Among those diagnosed with ROP (n = 315), 179 (56.8%) had incomplete screening, including 30 (n = 51, 58.8%) infants with stage 3 ROP.

Conclusion

Completeness of screening and ROP prevalence varied widely in the units. Of concern is the high proportion of infants with ROP, including stage 3 ROP, who do not complete screening. Measures to increase completeness of screening are needed to improve the detection of cases requiring treatment. The ROPSA register will allow these improvements to be monitored over time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is one of the most common avoidable causes of childhood blindness [1]. Low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), including those in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) are still experiencing what is termed the third epidemic of childhood blindness due to ROP [2]. Establishing efficient ROP screening programs to allow timely diagnosis and treatment of at risk infants is a key strategy to reduce childhood blindness due to ROP [3].

A 2018 global survey assessing the availability of ROP screening indicated little evidence for the presence of established ROP screening programs in most African countries [4]. Subsequent to this study, some SSA countries (i.e. Botswana, Ethiopia, Uganda, Tanzania) have established ROP screening programs and published data on the burden/frequency of ROP [5,6,7,8]. South Africa (SA) has regularly published data from several units over the past few decades. These studies report a wide range of ROP frequencies from 12.1% to 33.4% among screened preterm infants [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. However, most of these studies do not comment on completeness of screening or the proportion of infants diagnosed with ROP who do not complete screening.

Incomplete ROP screening has been identified as a challenge in high, middle and low-income settings [19,20,21]. In the recently established South African ROPSA register, up to 46% of infants who initiated screening in the Cape Town Metropole region did not complete screening [22]. The study raised concerns that this may underestimate the true prevalence of ROP and treatment requiring ROP. Most studies report the frequency of ROP among infants who complete screening and exclude data from infants in whom screening is initiated but not completed. Using data from the ROPSA register, this study aims to compare the characteristics of infants who start screening and describe the prevalence of ROP in infants with complete and incomplete screening at five units within the Cape Town Metropole region.

Subjects and methods

Study population

This prospective population-based study included infants screened for ROP at three tertiary-level units (A, B and C) and two secondary-level units (D and E) within the Cape Town Metropole region of the Western Cape, South Africa [23]. These units are responsible for ROP screening in the public sector of the Cape Town Metropole, which serves 75% of a regional population of 4.7 million [23, 24]. Importantly, these units share similar features: they have adopted similar supplemental oxygen therapy protocols for preterm infants, including target oxygen saturation levels set at 90–94/95%; they all have access to key neonatal care resources, including continuous positive airway pressure, oxygen blenders, and surfactant; and they use the same ROP screening criteria, guidelines and case definition of treatment requiring ROP (Type 1 ROP).

Data management

Data on all infants born and screened at the five units between 1 February 2023 and 30 April 2024 were extracted from the ROPSA register and analysed [22]. In most cases, screening was initiated where infants were born during admission [22]. Some infants were however, transferred between units for neonatal care purposes (i.e. Unit C to B or D vs Unit A to E). To prevent duplicate entries, infants were allocated to the unit that initiated screening even if follow-up examinations were subsequently performed at another unit. Demographic, neonatal, and ROP screening data were extracted for all preterm infants screened according to the regional screening criteria of birth weight (BW) < 1250 grams or gestational age (GA) < 32 weeks.

Screening procedure

ROP screening was initiated at a postnatal age (PNA) of 4–6 weeks or postmenstrual age (PMA) of 31–33 weeks, whichever came latest [25]. This is in keeping with the National South African guidelines, which were amended from those used in the United Kingdom and the United States. Topical 2.5% cyclopentolate and 0.5% phenylephrine were instilled to dilate the pupils prior to screening. Screening at all the units was performed using binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy and a 28-dioptre lens. Examinations were performed by ophthalmologists or supervised ophthalmology trainees weekly or twice weekly. Based on the SA guidelines the screening process was noted as complete in infants with (a) full retinal vascularisation, or (b) completely regressed ROP, or (c) vascularisation to zone 3 without previous zone 1 or 2 ROP, or (d) attaining 45 weeks PMA with no Type 1 or Type 2 ROP disease or worse [25]. In addition, all infants diagnosed with treatment requiring ROP were considered to have completed screening.

In all five units, similar standardised templates were used to record retinal findings. These findings were described according to the International Classification of ROP guidelines (ICROP 3) [26]. The most advanced ROP stage diagnosed, in either eye, was assigned to each infant for analysis. Treatment-requiring ROP (or Type 1 ROP) was defined as (a) any stage of ROP in zone 1 with plus disease, or (b) stage 3 in zone 1 without plus disease, or (c) stage 2 or 3 ROP with plus disease in zone 2 [27].

Statistical analysis

The analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc.). Infants screened at or prior to 6 weeks PNA or 33 weeks PMA were considered to be screened on time.

The categorical covariates (sex, gestation, the number screened on time, the number who completed screening, no ROP, any ROP and ROP stages) were described using the number (n,%) of infants. Proportional differences between units were analysed using Chi-square tests.

Birth weight (grams) and gestational age (weeks) data were described using means with standard deviations and ranges. Birth weight was log-transformed to normalise the distribution. The unit means were compared using ANOVA and t-tests for BW (log) and GA with overall p values for Chi-Square tests. Pairwise comparisons between unit p values were reported for z tests adjusted for the multiple comparisons (Tukey-Kramer).

The frequency of ROP was compared in infants with complete and incomplete screening using a generalised linear model with a binomial distribution and a log link. A p value of <0.05 indicated statistical significance. The p value for the overall difference was reported using a Chi-Square test and pairwise differences within units were reported using a z test.

Ethics

Ethical approval for this study and the ROPSA register was provided by the University of Cape Town's Health research ethics committee (HREC 346/2021 and R017/2021) and conducted based on the Declaration of Helsinki. A waiver of consent was obtained for the analysis of the anonymised dataset.

Results

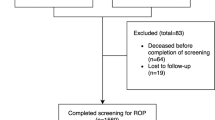

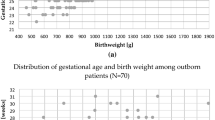

Screening for ROP in the region was initiated in 933 infants during the study period. Among these infants, there were 484 (51.9%) females and 752 (81.1%) singletons. In this total study group, the mean GA was 28.8 (SD 1.7) weeks with a mean BW of 1102.2 (SD 240.7) grams. The GA and BW of infants screened in the five different units are presented in Table 1. The tertiary units (A, B and C) screened 809 (86.7%) infants.

Screening in the region was initiated on time according to the guidelines, in 749 (80.3%) infants. The proportion of infants screened on time (i.e. at or prior to a PNA of 6 weeks or PMA of 33 weeks) in the five units ranged from 70.8% to 83.9% (p = 0.279). Screening in the units started between a PNA of 1–15 weeks and a PMA of 29–48 weeks. The cumulative percentage of infants screened at each PNA and PMA are illustrated in Fig. 1A, B.

Completed screening

A total of 468 (50.2%) infants completed screening in the region. The proportion of infants in each unit who completed screening ranged from 36.8% to 74.6% (Table 2).

The mean GA and BW in those that completed screening in the region was 29.0 (SD 1.8) weeks and 1142.7 (SD 258.4) grams, respectively. The mean GA of infants in the various units who completed screening ranged from 28.6 to 29.7 weeks, with the mean BW ranging from 1067.0 to 1270.5 grams; (p < 0.001, p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Diagnosis of ROP among the screened cohorts

Among the 933 infants in the region in whom screening was initiated, 315 (33.8%, 95% CI 30.9%–36.9%) were diagnosed with ROP. The proportions of infants diagnosed with ROP in Unit A-E were 33.4% (158/473), 16.1% (33/205), 39.7% (52/131), 48.6% (35/72), and 71.2% (37/52), respectively (p < 0.001 for overall difference) (Table 3). Further, a maximum of stage 1 or 2 was diagnosed in 264 (28.3%) and stage 3 in 51 (5.5%) of the infants. Type 1 ROP was diagnosed in 16 (1.7%) infants. One infant demised prior to treatment and the other 15 were treated. No infants were diagnosed with stage 4 or 5 ROP.

In the 468 (50.2%) infants who completed screening, 136 (29.1%) were diagnosed with ROP. A maximum of stage 1 or 2 was diagnosed in 115 (24.6%) and stage 3 in 21 (4.6%) of these infants. The proportion of these infants diagnosed with ROP in the units ranged from 13.1% to 64.3% (Table 3).

Overall, 465 (49.8%) infants in the region had incomplete screening. The proportion of infants with incomplete screening in each unit ranged from 25.4% to 63.2% (Table 3). Among these infants, 179 (38.5%) were diagnosed with ROP. A maximum of stage 1 or 2 was diagnosed in 149 (32.0%) and stage 3 in (30, 6.5%). The proportion of these infants diagnosed with ROP in the units ranged from 25.0% to 79.2% (Table 3).

Among the infants diagnosed with ROP in this region (n = 315), 179 (56.8%) had incomplete screening. This included 56.4% (149/264) of those diagnosed with a maximum of stage 1 and 2 and 58.8% (30/51, 58.8%) of those with a maximum of stage 3.

The reason for incomplete screening in the region was failure to attend scheduled follow-up examinations in 446 (95.9%), death in 15 (3.2%), referral outside of the region in 2 (0.4%), with no reason provided for 2 (0.4%) infants. Failure to attend follow-up examinations was also the most common reason for incomplete screening in Unit A-E: 95.6% (289/299), 100% (52/52), 92.7% (51/55), 94.3% (33/35), 100% (24/24), respectively.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first population-based study to describe the prevalence of ROP and completeness of screening in units within the same region. The five units within this Sub-Saharan African region demonstrated a wide variation in the prevalence of ROP and completeness of screening.

Screening was initiated on time in 80% of infants in this region, an encouraging finding when compared to recent population-based studies in India (43%, n = 751), the Netherlands (78.2%, n = 849), and France (75.7%, n = 2 169) [28,29,30]. Timely initiation of screening enables the diagnosis of ROP prior to progression to advanced stages.

The prevalence of ROP can vary within a country [7, 31, 32]. Our study found that ROP prevalence varies in units within the same region. While these units have adopted similar ROP screening and neonatal protocols, differences in adherence to these protocols may account for the different ROP prevalences. Another explanation is the difference in the characteristics (i.e. GA and BW) of infants screened in the units. Lower GAs and BWs are associated with an increased risk of developing ROP [33]. Due to regional neonatal policy, less mature preterm infants are born in tertiary Units A and C. The finding that Unit E, a secondary unit, had the highest proportion of infants diagnosed with ROP was surprising. However, the GA and BW of the screened infants were similar to tertiary Unit A and C. In the ROPSA register infants are assigned to the unit which starts ROP screening. Some infants may have been transferred from tertiary Unit A, with ROP screening initiated in Unit E. The diagnosis of ROP in 64% of infants completing screening in Unit E is the highest reported by any unit in South Africa [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Infants transferred from tertiary to secondary level care prior to completed screening may have an increased risk of developing ROP in this region. Currently, the ROPSA register does not collect data on the transfer of patients between units. Data on transfers may be useful in this region, especially since transfer between units before starting or completing ROP screening increases the risk of incomplete screening [30, 34, 35].

Incomplete screening is reported to be as high as 46% (n = 318/696) in the Cape Town Metropole region [22]. The present study confirmed this high level of incomplete screening in the region (50%, n = 465/933) and identifies a wide variation in the different units within this region, as low as 25% (Unit B, n = 52/205) and as high as 63% (Unit A, n = 299/473). These figures are higher than other SSA units: 8.8% (n = 12/135) [16], 10% (n = 53/526) [11], 22% (27/121) [12] in SA versus 13% (n = 54/424) [36], 21% (n = 52/245) [8] in other African countries. This is the first SA study to explore reasons for incomplete screening. Failure to attend scheduled follow-up examinations was the most common reason in the units and the region. A recent study (n = 66), assessed different reasons for the failure to attend scheduled outpatient ROP screening examinations. The authors analysed the role of maternal ethnicity, median family income, GA and BW. The study found low birth weight to be the only significant factor associated with loss to follow-up [20]. Screening in the units was initiated on time for the majority of infants, most likely because infants were still inpatients. While data on the inpatient or outpatient status of infants at the time of screening is currently not collected on the ROPSA register, we suspect that outpatient appointments may contribute to incomplete screening in this region and underlying reasons need to be explored.

It is concerning that most (57%, 179/315) infants diagnosed with ROP in this region do not complete screening. This includes 59% (30/51) of those known to have developed stage 3 ROP. Based on the large randomised Early Treatment for Retinopathy of Prematurity study in the United States, infants with stage 3 ROP have a 12% -16% risk of progression to Type 1 ROP [37]. Improving completeness of screening will provide a more reliable estimate of the prevalence of ROP and Type 1 ROP in this region, which may be higher than previously estimated. More importantly, it will reduce the risk of missing infants that need treatment to reduce the risk of blindness [27]. Strategies to encourage adherence to follow-up examinations, especially in infants known to have developed ROP are needed. Measures that have worked in other LMICS include: counselling caregivers about the importance of screening, travel reimbursement for infants with severe ROP, recording alternative contact numbers for caregivers, and the appointment of a project manager to liaise with caregivers [38].

The strength of this study is the use of the ROPSA register which collects population level ROP screening data while monitoring the underlying screening process. This has allowed us to quantify infants with incomplete screening and the proportion of these infants diagnosed with ROP. This study highlights that the three tertiary units (A-C) screened almost 90% of the infants and diagnosed 15 of the 16 infants who developed Type 1 ROP. While Unit A initiates screening in half the infants in this region, an alarming 63% of these infants did not complete screening. Such data can be used to guide the allocation of resources to improve ROP screening at a regional level.

While this study analysed some risk factors for developing ROP (i.e. BW, GA, sex), the inclusion of additional risk factors was beyond the scope of this study. This is a limitation, since differences in risk factors may contribute the ROP prevalences in the units. Based on the ROPSA data these can be analysed in the future.

In conclusion, our findings confirm that a large proportion of infants in this South African region do not complete ROP screening, and this varies in the units. The current prevalence of ROP may be underestimated in these units which provide ROP screening to most infants in this region. Sustaining the ROPSA register with the addition of key data will allow continuous monitoring of completeness of screening, ROP frequency, and aid in identifying reasons for the observed differences. Given the wide variability in prevalence, it is important that data should be collected from every screening neonatal unit. Sampling from only some of the units, especially only tertiary, is likely to underestimate the true burden of ROP.

Our findings will be shared with stakeholders in the different units. Measures to improve completeness of screening will need to be identified and implemented to optimise the care and visual outcome in preterm infants in this region.

Summary

What was known before:

-

The prevalence of retinopathy of prematurity can vary within a country.

What this study adds:

-

The prevalence of retinopathy of prematurity can vary in units located within the same region; regardless of similarities in neonatal care and screening protocols.

Data availability

The data from the study are available on reasonable request from the corresponding author.

References

Solebo AL, Teoh L, Sargent J, Rahi JS. Avoidable childhood blindness in a high-income country: findings from the British Childhood Visual Impairment and Blindness Study 2. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023;107:1787–92. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo-2022-321718.

Herrod SK, Adio A, Isenberg SJ, Lambert SR. Blindness secondary to retinopathy of prematurity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2022;29:156–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/09286586.2021.1910315.

Varughese S, Gilbert C, Pieper C, Cook C. Retinopathy of prematurity in South Africa: an assessment of needs, resources and requirements for screening programmes. Br J Ophthalmol. 2008;92:879–82. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjo.2008.137588.

Mora JS, Waite C, Gilbert CE, Breidenstein B, Sloper JJ. A worldwide survey of retinopathy of prematurity screening. Br J Ophthalmol. 2018;102:9–13.

Sherief ST, Taye K, Teshome T, Demtse A, Gilbert C. Retinopathy of prematurity among infants admitted to two neonatal intensive care units in Ethiopia. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2023;8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjophth-2023-001257

Gezmu AM, Shifa JZ, Quinn GE, Nkomazana O, Ngubula JC, Joel D, et al. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in botswana: a prospective observational study. Clin Ophthalmol. 2020;14:2417–25. https://doi.org/10.2147/OPTH.S265664.

Ndyabawe I, Namiiro F, Muhumuza AT, Nakibuka J, Otiti J, Ampaire A, et al. Prevalence and pattern of retinopathy of prematurity at two national referral hospitals in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Ophthalmol. 2023;23:478. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12886-023-03195-7.

Mhina C, Mtogo Y, Mafwiri M, Sanyiwa A, Mosenene NS, Malik ANJ. Prevalence and associated factors for retinopathy of prematurity at a tertiary hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Eye. 2025. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-025-03651-2.

Straker CA, Van Der Elst CW. The incidence of retinopathy of prematurity at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town. S Afr Med J. 1991;80:287–8.

Kirsten GF, Van Zyl JI, Le Grange M, Ancker E, Van Zyl F. The outcome at 12 months of very-low-birth-weight infants ventilated at Tygerberg Hospital. S Afr Med J. 1995;85:649–54.

Mayet I, Cockinos C. Retinopathy of prematurity in South Africans at a tertiary hospital: a prospective study. Eye. 2006;20:29–31. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.eye.6701779.

Delport SD, Swanepoel JC, Odendaal PJ, Roux P. Incidence of retinopathy of prematurity in very-low-birth-weight infants born at Kalafong Hospital, Pretoria. S Afr Med J. 2002;92:986–90.

Jacoby MR, Du Toit L. Screening for retinopathy of prematurity in a provincial hospital in Port Elizabeth, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2016;106. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i6.10663

Visser Kift E, Freeman N, Cook C, Myer L. Retinopathy of prematurity screening criteria and workload implications at Tygerberg Children’s Hospital, South Africa: a cross-sectional study. S Afr Med J. 2016;106. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i6.10358

Freeman N, Smith J, Bekker A, Van der Merwe SK, Harvey J. Prevalence of and risk factors for retinopathy of prematurity in a cohort of preterm infants treated exclusively with non-invasive ventilation in the first week after birth: research. S Afr Med J. 2013;103:96–100. https://doi.org/10.7196/samj.6131.

Keraan Q, Tinley C, Horn A, Pollock T, Steffen J, Joolay Y. Retinopathy of prematurity in a cohort of neonates at Groote Schuur Hospital, Cape Town, South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2016;107:64–9. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v107.i1.11226.

Dadoo Z, Ballot D. An evaluation of the screening for retinopathy of prematurity in very-low-birth-weight babies at a tertiary hospital in Johannesburg. SAJCH. 2016;10:79–82. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJCH.2016.v10i1.1099.

Seobi T, Maposa I, Makgotloe MA. Retinopathy of prematurity screening in Johannesburg, South Africa: a comparative study. Afr Vis Eye Health. 2022;81:5 https://doi.org/10.4102/aveh.v81i1.771.

Ademola-Popoola DS, Fajolu IB, Gilbert C, Olusanya BA, Onakpoya OH, Ezisi CN, et al. Strengthening retinopathy of prematurity screening and treatment services in Nigeria: a case study of activities, challenges and outcomes 2017-2020. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2021;6:e000645 https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjophth-2020-000645.

Santineau K, Abikoye TM, Guerin CM. Determinants of compliance with outpatient examinations for infants at risk for retinopathy of prematurity. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2024;28:103813.

McCahon H, Chen V, Paz EF, Steger R, Alexander J, Williams K, et al. Improving follow-up rates by optimizing patient educational materials in retinopathy of prematurity. J Am Assoc Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2023;27:134 e1-e5.

van der Lecq T, Rhoda N, Jordaan E, Seobi T, Visser L, Gilbert C, et al. Screening for retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) in South Africa: data from a newly established prospective regional register. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2025;10. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjophth-2024-002036

Africa LGhS. Municipalities: Yes Media; 2024 https://municipalities.co.za/map/6/city-of-cape-town-metropolitan-municipality.

Africa SS. General household survey 2022 [updated 2022. 105-7]. Available from: https://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/P0318/P03182022.pdf. Accessed 21 Feb 2024.

Visser L, Singh R, Young M, Lewis H, McKerrow N. Guideline for the prevention, screening and treatment of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP). S Afr Med J. 2012;103:116–25. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAMJ.2016.v106i6.10358.

Chiang MF, Quinn GE, Fielder AR, Ostmo SR, Paul Chan RV, Berrocal A, et al. International classification of retinopathy of prematurity, third edition. Ophthalmology. 2021;128:e51–e68. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2021.05.031.

Good WV. Final results of the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity (ETROP) randomized trial. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2004;102:233–50.

Sabherwal S, Gilbert C, Foster A, Kumar P. ROP screening and treatment in four district-level special newborn care units in India: a cross-sectional study of screening and treatment rates. BMJ Paediatr Open. 2021;5:e000930.

Trzcionkowska K, Termote JU, Böhringer S, van Sorge AJ, Schalij-Delfos N. Nationwide inventory on retinopathy of prematurity screening in the Netherlands. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023;107:712–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjophthalmol-2021-319929.

Chapron T, Caputo G, Pierrat V, Kermorvant E, Barjol A, Durox M, et al. Screening for retinopathy of prematurity in very preterm children: the EPIPAGE-2 cohort study. Neonatology. 2021;118:80–9. https://doi.org/10.1159/000513225.

Holmström G, Tornqvist K, Al-Hawasi A, Nilsson Å, Wallin A, Hellström A. Increased frequency of retinopathy of prematurity over the last decade and significant regional differences. Acta Ophthalmol. 2018;96:142–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/aos.13549.

Thomas K, Shah P, Canning R, Harrison A, Lee S, Dow K. Retinopathy of prematurity: risk factors and variability in Canadian neonatal intensive care units. J Neonatal-Perinat Med. 2015;8:207–14.

Yu CW, Popovic MM, Dhoot AS, Arjmand P, Muni RH, Tehrani NN, et al. Demographic risk factors of retinopathy of prematurity: a systematic review of population-based studies. Neonatology. 2022;119:151–63. https://doi.org/10.1159/000519635.

Van Sorge A, Termote J, Simonsz H, Kerkhoff F, Van Rijn L, Lemmens W, et al. Outcome and quality of screening in a nationwide survey on retinopathy of prematurity in The Netherlands. Br J Ophthalmol. 2014;98:1056–60.

Attar MA, Gates MR, Iatrow AM, Lang SW, Bratton SL. Barriers to screening infants for retinopathy of prematurity after discharge or transfer from a neonatal intensive care unit. J Perinatol. 2005;25:36–40. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.jp.7211203.

Mutangana F, Muhizi C, Mudereva G, Noë P, Musiime S, Ngambe T, et al. Retinopathy of prematurity in Rwanda: a prospective multi-centre study following introduction of screening and treatment services. Eye. 2020;34:847–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-019-0529-5.

Christiansen SP, Dobson V, Quinn GE, Good WV, Tung B, Hardy RJ, et al. Progression of type 2 to type 1 retinopathy of prematurity in the early treatment for retinopathy of prematurity study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:461–5.

Vinekar A, Jayadev C, Dogra M, Shetty B. Improving follow-up of infants during retinopathy of prematurity screening in rural areas. Indian Pediatr. 2016;53:S151–S4.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge members of the ROPSA collaborative group from the participating units.

Funding

Funding for this study was provided to corresponding author (TV) by the following: Discovery Foundation (Academic Research Fellowship award), South African Department of Higher Education and Training (USDP grant), and the South African Medical Research Council (Division of Research Capacity Development under the Bongani Mayosi National Health Scholars Programme funding received from the Public Health Enhancement Fund / South African National Department of Health). The content is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not represent the official views of the SAMRC. Research related travel expenses for GH were provided by the Swedish fund, Ögonfonden/ Stiftelsen Synfrämjandets Forskningsfond. These organisations had no role in the study design, conduct of the research, or drafting of the final manuscript. Open access funding provided by University of Cape Town.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

TV: study design, drafting of the manuscript, interpretation of the data. GH: study design, drafting of the manuscript, interpretation of the data, EJ: data analysis, drafting of the manuscript interpretation of the data. PN: drafting of the manuscript, interpretation of the data. NR: study design, interpretation of the data. RM: study design, drafting of the manuscript, interpretation of the data. All authors: provided approval of the final manuscript. ROPSA Collaborative Group members provided participants for the study.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Van der Lecq, T., Holmström, G., Jordaan, E. et al. Variations in prevalence of retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) and completeness of screening in five units within a South African region: a register-based study. Eye (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-026-04257-y

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41433-026-04257-y