Abstract

Glutamatergic activity in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM), which is an important brain area where angiotensin II (Ang II) elicits its pressor effects, contributes to the onset of hypertension. The present study aimed to explore the effect of central Ang II type 1 receptor (AT1R) blockade on glutamatergic actions in the RVLM of stress-induced hypertensive rats (SIHR). The stress-induced hypertension (SIH) model was established by electric foot shocks combined with noises. Normotensive Sprague–Dawley rats (control) and SIHR were intracerebroventricularly infused with the AT1R antagonist candesartan or artificial cerebrospinal fluid for 14 days. Mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), plasma norepinephrine (NE), glutamate, and the expression of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid (NMDA) receptor subunit NR1, and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors in the RVLM increased in the SIH group. These increases were blunted by candesartan. Bilateral microinjection of the ionotropic glutamate receptor antagonist kynurenic acid, the NMDA receptor antagonist d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate, or the AMPA/kainate receptors antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione into the RVLM caused a depressor response in the SIH group, but not in other groups. NR1 and AMPA receptors expressed in the glutamatergic neurons of the RVLM, and glutamate levels, increased in the intermediolateral column of the spinal cord of SIHR. Central Ang II elicits release of glutamate, which binds to the enhanced ionotropic NMDA and AMPA receptors via AT1R, resulting in activation of glutamatergic neurons in the RVLM, increasing sympathetic excitation in SIHR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Psychosocial stress, which is gradually increasing with increased pace in modern society, is an important risk factor for hypertension. Excessive stress results in the generation of stress-induced hypertension (SIH), which is mainly associated with enhancement of renin–angiotensin system (RAS) activity. Angiotensin II (Ang II) has an important effect on central control of sympathetic functions [1]. All of the components responsible for synthesis of endogenous Ang II are present in the brain [2]. Ang II mainly activates two receptor subtypes, the angiotensin type 1 receptor (AT1R) and angiotensin type 2 receptor (AT2R). Central or peripheral Ang II has been shown to cause sympathetic activation via AT1R [3]. AT1R in the brain participates in central regulation of the sympathetic response to stress [4]. Isolation and cold-restraint stress increased circulation and brain RAS activities by increasing Ang II formation and AT1R expression, while blockade of AT1R prevented the sympathetic response to stress [5, 6].

The rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) is a brain region rich in sympathetic premotor neurons and is a central site where Ang II elicits its pressor effects via AT1R [7]. RVLM neurons innervate sympathetic preganglionic neurons in the intermediolateral column (IML) of the spinal cord, which in turn innervates the heart and blood vessels with sympathetic nerves [8, 9]. RAS over-activity in the RVLM has been shown in Ang II-induced hypertension and in spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) [10,11,12]. AT1R antagonists have been widely used for the treatment of hypertension, but the molecular mechanisms remain unclear.

Glutamate (Glu) is a major excitatory neurotransmitter and regulates sympathetic nerve activity in several brain areas. A previous study has reported that blockade of Glu receptors in the IML interrupted the ability of electrical activation of sympathetic premotor neurons in the RVLM to excite sympathetic preganglionic neurons. Within the IML, antergradely labeled terminals of RVLM neurons were found to contain Glu immunoreactivity. It provided the evidence as glutamatergic (pre-sympathetic) neurons in the RVLM connecting to the IML [13, 14]. Glu acts through Glu receptors, including metabotropic Glu receptors and ionotropic Glu receptors. There are two subtypes of ionotropic Glu receptors: N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA receptor subtypes. Non-NMDA receptors are divided into α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) and kainate receptors [15, 16]. Increased activation of Glu receptors and AT1R were involved in chronic sympathetic hyperactivity. Microinjection of a Glu receptor blocker or AT1R blocker to the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) did not affect blood pressure (BP) or sympathetic activity of normotensive rats [17], but reduced heart rate (HR) and BP in SHR and in rats with chronic heart failure (CHF) [18, 19]. Upregulation of the NMDA receptor subunit NR1 (NMDAR1) in the PVN led to enhanced glutamatergic activity and might result in increased sympathetic activity in CHF [20]. Accordingly, it is proposed that sympathetic hyperactivity is related to increased excitatory glutamatergic and angiotensinergic actions. Moreover, microinjection of the ionotropic Glu receptor antagonist kynurenic acid (Kyn) into the RVLM resulted in a profound decrease in BP in renovascular hypertensive rats. Furthermore, the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor captopril blocked the depressor response to Kyn [21], suggesting that Ang II might upregulate glutamatergic inputs to the RVLM in hypertension.

Renovascular hypertensive rats have dramatically increased AT1R and ACE expression in the PVN [10]. Ang II was increased and AT1R was upregulated in the RVLM in CHF [22]. Our previous studies demonstrated that AT1R and ACE messenger RNA (mRNA) and protein expression were significantly higher in stress-induced hypertensive rats (SIHR) than in control rats [23]. In this study, we evaluated the hypothesis that Ang II might enhance Glu production and NMDA/AMPA receptor expression in the RVLM via AT1R activation, which might activate glutamatergic neurons in the RVLM, contributing to the generation of hypertension in SIHR.

Methods

Animals

Adult male Sprague–Dawley rats, each weighing 200–220 g, were housed in a room with light (12 h/day). All experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of School of Basic Medical Sciences, Fudan University, and performed according to the guidelines of the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

SIH model

The SIH model was established as described in our previous studies [24, 25]. Rats in the SIH group received 2-h random electric foot shocks and interval noise stimulation twice daily for l5 days. Measurement of systolic blood pressure (SBP) was carried out using the tail-cuff method and repeated three times to obtain an average value. After 15 days of stimulation, rats in the SIH group with SBP <140 mmHg were removed from subsequent experiments.

MAP measurements

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) of conscious rats was measured using a noninvasive computerized tail-cuff system (CODATM 2, Kent Scientific, USA), as described previously [26]. After tracheal intubation, the right carotid artery was cannulated with polyethylene catheters to record BP continuously using a bioelectric signals system (PowerLab 3508, AD Instruments, Australian). HR was derived from the BP wave automatically.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Plasma norepinephrine (NE) concentrations were detected by an NE ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) kit (Immuno-Biological Laboratories, Minneapolis, MN, USA) [27]. Experimental procedures for ELISA were carried out according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Immunofluorescence staining

Immunofluorescence staining procedures were performed as reported previously [28]. The rats were euthanized and the brains were removed, fixed, frozen, and coronally sectioned (20 μm). Sections were incubated in 2% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 0.01 mol/L phosphate-buffered saline and then incubated with two primary antibodies, including a rabbit polyclonal anti-NMDAR1 (1:100, Abcam)/rabbit polyclonal anti-AMPA subtype (Glu receptor 1, GluR1) (1:100, Abcam) and a goat polyclonal anti-vesicular Glu transporter 2 (vGLUT2, 1:100, Santa Cruz) overnight at 4 °C. After washing three times, sections were incubated with the corresponding secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor 594-labeled donkey anti-goat immunoglobulin G (IgG), 1:200 and Alexa Fluor 488-labeled donkey anti-rabbit IgG, 1:200). Fluorescence of the sections was examined by a Zeiss LSM 710 (Germany) confocal laser system.

Chronic ICV infusion

The rats were anesthetized with urethane (0.75 g/kg) and α-chloralose (70 mg/kg) intraperitoneally, placed in a stereotaxic apparatus (NeuroStar, USA), and implanted with an intracerebroventricular (ICV) cannula for infusion of the AT1R antagonist candesartan (CAN), as described previously [29]. On the second day during stress, an ICV cannula was implanted into the right lateral cerebral ventricle (0.8 mm caudal to bregma, 1.5 mm lateral to the bregma, and 3.8 mm ventral to the 0 level), and connected to a 14-day mini-osmotic pump (ALZET, model 2002) through a plastic tube to deliver CAN (4 μg/day) or artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). After the experiments, 5 μl of Evans blue dye was injected to the lateral cerebral ventricle to confirm the position of the cannula. Rats were randomly divided into four groups: normotensive rats treated with aCSF (control), normotensive rats treated with CAN (control+CAN), SIH rats treated with aCSF (SIH), and SIH rats treated with CAN (SIH+CAN).

RVLM microinjections

After 15 days of treatment, as described previously [30], microinjection of test agents to the RVLM was performed using a micropipette connected to a 1 μl Hamilton microsyringe. The position of the RVLM was 0.8–1.0 mm ahead of the most rostral rootlet of the hypoglossal nerve, 1.8–2.0 mm lateral to the midline, and 0.6–0.8 mm below the ventral surface. Accurate placement of the pipette and functional identification of the RVLM were accomplished by microinjection of L-Glu (2 nmol/0.1 μl). The microinjection agents were Kyn, NMDA receptor antagonist d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate (AP-5), and AMPA//kainate receptor antagonist 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA).

RVLM microdialysis and IML microdialysis

In RVLM microdialysis experiments, a microdialysis probe (MAB, Sweden) was inserted into the RVLM. The position was identified as mentioned above. For IML microdialysis, after making an incision in the back to expose the T8 level of the thoracic segment and then removing the bone and meningeal membrane to expose the spinal cord surface, the microdialysis probe was inserted into the T8 level of the spinal cord, 0.45 mm lateral to midline, and 0.9 mm below the dorsal surface. Microdialysis was performed by perfusing the probe with aCSF using a microdialysis pump (Bioanalytical Systems, USA) at a rate of 2 μl/min. Each dialysate sample was harvested for 10 min.

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC)

Glu in dialysate samples was measured by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), as reported previously [23]. Amino acids of dialysate samples were analyzed by reverse-phase HPLC and fluorescence detection (Waters, USA) using a reverse-phase column. The derivatized reagent consisted of 5 ml absolute ethanol, 5 ml 0.1 mol/L sodium tetraborate, 27 mg orthophthaldialdehyde, and 40 μl β-mercaptoethanol (Sigma-Aldrich, USA). The sample (20 μl) was mixed with the derivatized reagent (10 μl) for 90 s and then injected onto the HPLC system. The mobile phase, which was composed of 63% 0.1 mol/L KH2PO4, 35% methanol, and 2% tetrahydrofuran, flowed through the system at a rate of 1.0 ml/min. The excitation and emission wavelengths were 330 and 450 nm, respectively.

Collection of blood and tissue samples

On the fifteenth day, rats were euthanized and the brains were removed and frozen. Both sides of the ventrolateral medulla covering the RVLM (0.5 and 1.5 mm rostral to the obex, 1.5–2.5 mm lateral to the midline, and medial to the spinal trigeminal tract) were collected using a stainless steel micropunch (1 mm internal diameter). At the zeroth, fifth, tenth, and fifteenth day, rats were gas anesthetized with isoflurane for blood collection. Blood was centrifuged for 20 min at 4 °C. Plasma was harvested and stored at −80 °C.

Western blot analysis

The samples of brain tissues were homogenized in RIPA lysis buffer with protease or phosphatase inhibitors (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and then centrifuged (12,000 rpm, 15 min, 4 °C) to obtain supernatants. The extracted total protein concentration of the supernatants was measured by a BCA assay kit (Pierce). Samples were loaded onto 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gels, transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, USA), and incubated with primary antibodies (rabbit anti-NMDAR1, rabbit anti-AMPA receptor (GluR1), or rabbit anti-tubulin, Abcam) at 4 °C overnight, washed with Tris-buffered saline with Tween (TBST), and then probed with the corresponding secondary antibody (horseradish peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG). After washing with TBST, bands were visualized using an ECL-Plus detection kit (Tiangen, China) and scanned with an ImageQuant LAS 4000 Mini (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, USA). Images were analyzed using the Image J densitometry system.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed as described previously [24]. Tissue sections were deparaffinized, rehydrated by a graded ethanol series, pre-incubated with 5% BSA, and incubated with rabbit anti-NMDAR1 antibody (1:100, Abcam) or rabbit anti-AMPA receptor (GluR1) antibody (1:100, Abcam) at 4 °C overnight. On the second day, sections were washed and incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody (biotin-labeled goat anti-rabbit IgG). All brain slices were serially sliced from 1.5 mm rostral to the obex, one for every six brain slices, five slices for each animal. The location of the RVLM was verified under a microscope at low magnification according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson [31]. Three different fields of view were randomly selected under high magnification, and the number of positive neurons was counted under magnification.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed by using Student’s t test, or one-way or two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

MAP, HR, and plasma NE of the stressed rats increase in a time-dependent manner

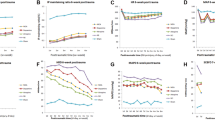

MAP and HR of stressed rats significantly increased from the sixth day compared with control rats or baseline (second day prior to stress) and stayed at a stable high level until the sixteenth day (Fig. 1a, b). Plasma NE in stressed rats significantly increased from the fifth day to the fifteenth day compared with control rats (Fig. 1c).

Effect of candesartan (CAN) on mean arterial pressure (MAP) (a), heart rate (HR) (b), and plasma norepinephrine (NE) (c, d) in control and stress-induced hypertension (SIH) groups. The rats were anesthetized and implanted with ICV cannula for infusion of the AT1R antagonist CAN on the second day during stress in SIHR and in the control group. Arrows indicate infusion time. Values are expressed as mean ± SE and statistical analysis was performed by using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) coupled with Tukey’s multiple comparison test in c, d, and two-way ANOVA coupled with Bonferroni post-tests in a, b, n = 7, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. baseline (second day prior to stress); #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. SIH

Chronic blockade of AT1R attenuates increases in MAP, HR, and plasma NE in SIHR

MAP and HR were significantly higher in the SIH group than in the control group. These increases were blunted by administration of CAN starting on the second day during stress (lasting 14 days) (Fig. 1a, b). Plasma NE was significantly higher in the SIH group than in the control group, and reduced in the SIH + CAN group compared with the SIH group on the fifteenth day (Fig. 1c, d).

Chronic blockade of AT1R attenuates increases in glutamate in the RVLM of SIHR

Baseline release of Glu in the RVLM of rats in the SIH group significantly increased compared with the control group, and was attenuated by chronic ICV infusion of CAN for 14 days (Fig. 2). There was no obvious difference in Glu concentration in the RVLM between the control and control + CAN groups.

Chromatographic plots of amino acids (a) and levels of glutamate (b) in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) of the control, stress-induced hypertension (SIH), control + candesartan (CAN), and SIH + CAN groups. Glu, glutamate; Gln, glutamine. Values are mean ± SE, n = 8, *P < 0.05 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. SIH

Chronic blockade of AT1R decreases expression of NMDAR1 and AMPA receptors in the RVLM of SIHR

Expression of NMDAR1 and AMPA receptors in the RVLM was significantly higher in the SIH group than in the control group (Fig. 3a, b). However, NMDAR1 and AMPA receptor expression in the RVLM was significantly decreased in the SIH + CAN group compared with the SIH group. No significant changes in NMDAR1 or AMPA receptor expression was observed between the control and control + CAN groups. NMDAR1-positive neurons were more abundant in the SIH group than in the control group. However, after ICV infusion of CAN for 14 days, NMDAR1-positive neurons were significantly decreased in the SIH + CAN group (Fig. 4a, c). Similarly, AMPA receptor-positive neurons were more abundant in the SIH group than in the control group, whereas the number of AMPA receptor-positive neurons was significantly reduced after CAN treatment (Fig. 4b, c).

Representative western blot (left) and densitometric analysis (right) of N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor subunit NR1 (NMDAR1) (a) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors (b) in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) of control, stress-induced hypertension (SIH), control + candesartan (CAN), and SIH + CAN groups. Values are presented as mean ± SE, n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. SIH

Representative immunohistochemistry image showing neurons positive for N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor subunit NR1 (NMDAR1) (a) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors (b) and a column diagram showing changes in the number of positive neurons (c) in the rostral ventrolateral medulla (RVLM) of control, stress-induced hypertension (SIH), control + candesartan (CAN), and SIH + CAN groups. Scale bars = 100 µm in a1, b1, c1, d1; 50 µm in a2, b2, c2, d2; 25 µm in a3, b3, c3, d3. Values are presented as mean ± SE, n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. SIH

Chronic blockade of AT1R attenuates decreases in MAP and HR induced by microinjection of Kyn, AP-5, or CNQX into the RVLM of SIHR

Bilateral microinjection of Kyn (50 nmol in 100 nl) to the RVLM in the anesthetized rats produced a profound decrease in BP, MAP, and HR in the SIH group compared with the control group, but had no obvious effect on BP, MAP, and HR in the other (SIH + CAN, control and control + CAN) groups (Fig. 5a). Bilateral microinjection of the NMDA receptor antagonist AP-5 (50 nmol in 100 nl) or the AMPA/kainate receptors antagonist CNQX (200 pmol in 100 nl) into the RVLM induced a similarly profound reduction in BP, MAP, and HR in the SIH group. However, no changes occurred in response to AP-5 or CNQX in the other groups. The peak changes of MAP and HR before and after bilateral microinjections of Kyn, AP-5, and CNQX in the four groups are shown in Fig. 5b, c. The RVLM was verified by a pressor response to l-Glu microinjection.

Representative original recordings of the effects of kynurenic acid (Kyn, 5 nmol in 100 nl) on blood pressure (BP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR) (a), and changes in MAP (b) and HR (c) induced by bilateral microinjection of Kyn, d-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoate (AP-5, 5 nmol in 100 nl), and 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (CNQX, 200 pmol in 100 nl) into the rostral ventrolateral medulla of control, stress-induced hypertension (SIH), control + candesartan (CAN), and SIH + CAN groups. The experiments were performed in the anesthetized state. Arrows indicate infusion time. Values are presented as mean ± SE, n = 5, *P < 0.05 vs. control; #P < 0.05 vs. SIH

NMDAR1 and AMPA receptors expressed in the glutamatergic neurons of the RVLM and the Glu release was increased in the IML of SIHR

NMDAR1 and AMPA receptors are expressed in glutamatergic neurons of the RVLM in SIHR (Fig. 6a, b), suggesting that Glu might activate glutamatergic neurons in the RVLM of SIHR. The Glu release in the IML was significantly increased in the SIH group compared with the control group (Fig. 6c).

Representative immunofluorescence image showing N-methyl-d-aspartic acid receptor subunit NR1 (NMDAR1) (a) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors (b) in glutamatergic neurons of the rostral ventrolateral medulla in the stress-induced hypertension (SIH) group and levels of glutamate in the intermediolateral column (IML) of the spinal cord of the control and SIH groups (c). Red areas represent staining of anti-vesicular glutamate transporter 2 (vGLUT2) (a marker of glutamatergic neurons) and green areas represent staining of NMDAR1 or AMPA receptors (glutamate receptor 1, GluR1). Double labeling is shown as yellow fluorescence. Scale bars = 50 µm. Values are presented as mean ± SE, n = 8, **P < 0.01 vs. control

Discussion

In the present study, we examined the role of central AT1R on the glutamatergic actions of the RVLM that regulate sympathetic activities in SIHR.

We showed that Ang II increased the sympathetic activity via AT1R in SIHR. MAP, HR, and plasma NE were significantly higher in the SIH group than in the control group. These effects were abolished by chronic ICV infusion of CAN, suggesting that central Ang II evoked sympathetic excitation via AT1R in SIHR. Ang II in the PVN enhances sympathetic activity and blockade of AT1R decreases sympathetic activity [32, 33]. Ang II elevates discharge of PVN neurons retrogradely labeled from the RVLM, suggesting that the PVN neurons that project to the RVLM respond to Ang II [34]. Microinjection of Ang II into the RVLM causes a pressor response, which can be attenuated by AT1R antagonists such as losartan or valsartan [35, 36]. Central administration of AT1R antagonists into the RVLM induces little response in normotensive rats, but elicits a depressor effect in SHR, renovascular hypertensive rats, and Dahl hypertensive rats [37,38,39]. Our results are consistent with findings that blockade of AT1R elicits a depressor effect in sympathetic hyperactivity models.

We also observed that AT1R plays a crucial role in increased Glu release and NMDA/AMPA receptor expression in the RVLM of SIHR. HPLC analysis showed that baseline release of Glu in the RVLM of SIH group was significantly increased. This increase was blocked by chronic ICV infusion of CAN. Glu concentration in the RVLM was also high in obesity-induced hypertension and the spontaneous hypertension models [40, 41]. Chronic administration of the AT1R antagonist olmesartan diminished the pressor effects of Glu or NMDA (an ionotropic Glu receptor agonist), but not (1S, 3R)-ACPD (a metabotropic Glu receptor agonist), in the RVLM of SHR [35], suggesting that Ang II might participate in the pressor response to Glu via ionotropic Glu receptors. In the current study, western blotting analysis and immunohistochemistry analysis showed that enhancement of NMDAR1 and AMPA receptors in the RVLM of SIHR was diminished by chronic ICV infusion of CAN for 14 days. A functional NMDA receptor consists of the NR1 subunit and one or more NR2 subunits [42, 43]. Ang II stimulated NR1 protein expression in neuronal NG-108 cells and losartan suppressed NR1 expression elicited by Ang II [44]. Increased BP induced by Ang II infusion resulted in an enhancement of plasma membrane NR1 in dendrites of PVN neurons, and NR1 deletion in PVN neurons alleviated the pressor response induced by Ang II [45, 46]. Therefore, our results indicated that NMDAR1 and AMPA receptors in the RVLM of SIHR were increased. These increases were inhibited by CAN. These results demonstrated that blockade of AT1R can diminish the release of Glu and expression of NMDA and AMPA receptors in the RVLM, resulting in alleviation of increased glutamatergic actions in the RVLM of SIHR.

We demonstrated that Ang II enhances glutamatergic actions in the RVLM via AT1R, resulting in modulation of cardiovascular activities in SIHR. Consistent with sympathetic hyperactivity models, bilateral microinjection of Kyn into the RVLM resulted in a profound decrease in MAP and HR in SIHR, but not in control rats, indicating that Glu receptors in the RVLM are engaged in generating sympathetic tone in SIHR. Previous studies have shown that NMDA receptors in the RVLM have a crucial effect on elevated BP in CHF and SHR [35, 47], but few studies have examined the role of AMPA receptors in hypertension. In this study, we found that microinjection of AP-5 or CNQX into the RVLM had similar inhibitory effects on MAP and HR in SIHR, but not in control rats, suggesting that both NMDA receptors and AMPA receptors in the RVLM might play similarly important roles in sympathetic activation in SIHR. Furthermore, the degree of MAP and HR decrease elicited by Kyn, AP-5, or CNQX was dramatically blunted in the SIH + CAN group compared with the SIH group, suggesting that activation of the ionotropic Glu/NMDA/AMPA receptors resulted in increased BP, and blockade of AT1R reduced ionotropic Glu/NMDA/AMPA receptor activation in SIHR. A previous study reported that central Ang II could promote the pressor response to l-Glu in the RVLM, whereas blockade of AT1R in the RVLM alleviated the pressor response induced by l-Glu in the same region [36], indicating that Ang II in the RVLM plays a crucial role in sympathetic activation evoked by glutamatergic actions. According to the above evidence, chronic blockade of AT1R is able to attenuate increased glutamatergic activity in the RVLM of SIHR, leading to decreased BP and sympathetic activity.

Studies have demonstrated a strong relationship between Ang II and reactive oxygen species (ROS) as important contributors to sympathetic excitation in rabbits with CHF [48]. Chronic infusion of Ang II into the brain of normal rabbits resulted in increased oxidative stress and ROS production in the RVLM, as well as upregulation of several protein subunits of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) oxidase, which are inhibited by losartan [49]. Microinjection of Ang II into the RVLM of normotensive rats significantly increased ROS production, which was significantly inhibited by co-administration of losartan [50]. Activation of the NADPH oxidase via AT1R is suggested to be the major source of ROS production, and altered downstream signaling is involved in the activation of RVLM neurons, leading to enhanced central sympathetic outflow and hypertension [51]. Therefore, AT1R-meditated ROS generation in the RVLM might also be an essential mechanism for increased BP and sympathetic activities in SIHR, which remains to be examined in future studies.

Finally, we showed that glutamatergic activity in the RVLM might activate glutamatergic neurons, resulting in Glu release in the IML to elicit pressor effects. NMDAR1 and AMPA receptors were expressed in glutamatergic neurons of the RVLM in SIHR. vGLUTs, which regulate transport of Glu into synaptic vesicles in presynaptic terminals, are classified into three types of vGLUTs: vGLUT1, vGLUT2, and vGLUT3. In general, vGLUT1 and vGLUT2 mRNAs are widely expressed in glutamatergic neurons of the brain, and vGLUT3 mRNA is typically expressed in some non-glutamatergic neurons [52, 53]. vGLUT1 and vGLUT2 are commonly used as specific biomarkers of glutamatergic neurons. vGLUT1 is abundantly present in the cerebral cortex, cerebellar cortex, and hippocampus, while vGLUT2 is present in the brainstem, thalamus, and deep cerebellar nuclei [54]. Therefore, in this study, we used vGLUT2 as a specific biomarker of glutamatergic neurons in the RVLM. Glutamatergic terminals in the hippocampus had NMDA autoreceptors, and NMDA can trigger Glu exocytosis in the presence of Mg2+ [55]. AMPA receptors and kainate receptors also could act as autoreceptors on glutamatergic terminals [56, 57]. Our results revealed that there might be NMDA autoreceptors and AMPA autoreceptors in glutamatergic neurons in the RVLM, and Glu might activate glutamatergic neurons in the RVLM. Glu has important effects on modulating sympathetic outflow through RVLM neurons, which project to the IML of the spinal cord. HPLC analysis showed that Glu significantly increased in the IML of SIHR, suggesting that activated glutamatergic neurons in the RVLM release more Glu to the IML of SIHR. These data suggest that Glu might activate glutamatergic neurons in the RVLM through NMDA and AMPA autoreceptors to release Glu to the IML to elicit pressor effects.

In conclusion, the findings of our study revealed that AT1R antagonists downregulated enhanced glutamatergic activity in the RVLM to regulate presser effects in SIHR. Our results indicated that central Ang II-mediated glutamatergic actions, due to the increased Glu, and upregulation of NMDA and AMPA receptors, may activate glutamatergic neurons in the RVLM to release Glu to the IML, altering elevated sympathetic activities in SIHR.

References

Kasal DA, Schiffrin EL. Angiotensin II, aldosterone, and anti-inflammatory lymphocytes: interplay and therapeutic opportunities. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:829786.

Kawabe T, Iwasa M, Kawabe K, Sapru HN. Attenuation of angiotensin type 2 receptor function in the rostral ventrolateral medullary pressor area of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2016;38:209–17.

Paul M, Poyan MA, Kreutz R. Physiology of local renin–angiotensin systems. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:747–803.

Armando I, Volpi S, Aguilera G, Saavedra JM. Angiotensin II AT1 receptor blockade prevents the hypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor response to isolation stress. Brain Res. 2007;1142:92–9.

Pavel J, Benicky J, Murakami Y, Sanchez-Lemus E, Saavedra JM. Peripherally administered angiotensin II AT1receptor antagonists are anti-stress compoundsin vivo. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2008;1148:360–6.

Saavedra JM, Armando I, Bregonzio C, Juorio A, Macova M, Pavel J, et al. A centrally acting, anxiolytic angiotensin II AT1 receptor antagonist prevents the isolation stress-induced decrease in cortical CRF1 receptor and benzodiazepine binding. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:1123–34.

Patel D, Böhlke M, Phattanarudee S, Kabadi S, Maher TJ, Ally A. Cardiovascular responses and neurotransmitter changes during blockade of angiotensin II receptors within the ventrolateral medulla. Neurosci Res. 2008;60:340–8.

Oshima N, Kumagai H, Onimaru H, Kawai A, Pilowsky PM, Iigaya K, et al. Monosynaptic excitatory connection from the rostral ventrolateral medulla to sympathetic preganglionic neurons revealed by simultaneous recordings. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:1445–54.

Guyenet PG. The sympathetic control of blood pressure. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:335–46.

Sriramula S, Cardinale JP, Lazartigues E, Francis J. ACE2 overexpression in the paraventricular nucleus attenuates angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;92:401–8.

Li HB, Qin DN, Cheng K, Su Q, Miao YW, Guo J, et al. Central blockade of salusin beta attenuates hypertension and hypothalamic inflammation in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11162.

Williamson CR, Khurana S, Nguyen P, Byrne CJ, Tai TC. Comparative analysis of renin–angiotensin system (RAS)-related gene expression between hypertensive and normotensive rats. Med Sci Monit Basic Res. 2017;23:20–4.

Morrison SF. Glutamate Transmission in the Rostral Ventrolateral Medullary Sympathetic Premotor Pathway. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2003;23:761–72.

Minson J, Pilowsky P, Llewellyn-Smith I, Kaneko T, Kapoor V, Chalmers J. Glutamate in spinally projecting neurons of the rostral ventral medulla. Brain Res. 1991;555:326–31.

Herman JP, Eyigor O, Ziegler DR, Jennes L. Expression of ionotropic glutamate receptor subunit mRNAs in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 2000;422:352–62.

Wang L, Zeng J, Yuan W, Su D, Wang W. Comparative study of NMDA and AMPA/kainate receptors involved in cardiovascular inhibition produced by imidazoline-like drugs in anaesthetized rats. Exp Physiol. 2007;92:849–58.

Gabor A, Leenen FH. Mechanisms in the PVN mediating local and central sodium-induced hypertension in Wistar rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;296:R618–30.

Li DP, Pan HL. Glutamatergic inputs in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus maintain sympathetic vasomotor tone in hypertension. Hypertension. 2007;49:916–25.

Zheng H, Li YF, Wang W, Patel KP. Enhanced angiotensin-mediated excitation of renal sympathetic nerve activity within the paraventricular nucleus of anesthetized rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297:R1364–74.

Li YF, Cornish KG, Patel KP. Alteration of NMDA NR1 receptors within the paraventricular nucleus of hypothalamus in rats with heart failure. Circ Res. 2003;93:990–7.

Carvalho THF, Bergamaschi CT, Lopes OU, Campos RR. Role of endogenous angiotensin II on glutamatergic actions in the rostral ventrolateral medulla in goldblatt hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2003;42:707–12.

Zucker IH. Novel mechanisms of sympathetic regulation in chronic heart failure. Hypertension. 2006;48:1005–11.

Du D, Chen J, Liu M, Zhu M, Jing H, Fang J, et al. The effects of angiotensin II and angiotensin-(1–7) in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of rats on stress-induced hypertension. PLos ONE. 2013;8:e70976.

Xiao F, Jiang M, Du D, Xia C, Wang J, Cao Y, et al. Orexin a regulates cardiovascular responses in stress-induced hypertensive rats. Neuropharmacology. 2013;67:16–24.

Zhang C, Xia C, Jiang M, Zhu M, Zhu J, Du D, et al. Repeated electroacupuncture attenuating of apelin expression and function in the rostral ventrolateral medulla in stress-induced hypertensive rats. Brain Res Bull. 2013;97:53–62.

Agarwal D, Haque M, Sriramula S, Mariappan N, Pariaut R, Francis J. Role of proinflammatory cytokines and redox homeostasis in exercise-induced delayed progression of hypertension in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2009;54:1393–400.

Kapusta DR, Pascale CL, Kuwabara JT, Wainford RD. Central nervous system Galphai2-subunit proteins maintain salt resistance via a renal nerve-dependent sympathoinhibitory pathway. Hypertension. 2013;61:368–75.

Hu L, Zhu D, Yu Z, Wang JQ, Sun Z, Yao T. Expression of angiotensin II type 1 (AT1) receptor in the rostral ventrolateral medulla in rats. J Appl Physiol. 2002;92:2153–61.

Dange RB, Agarwal D, Masson GS, Vila J, Wilson B, Nair A, et al. Central blockade of TLR4 improves cardiac function and attenuates myocardial inflammation in angiotensin II-induced hypertension. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;103:17–27.

Jiang M, Zhang C, Wang J, Chen J, Xia C, Du D, et al. Adenosine A(2A) R modulates cardiovascular function by activating ERK1/2 signal in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of acute myocardial ischemic rats. Life Sci. 2011;89:182–7.

Paxinos G, Watson CR, Emson PC. AChE-stained horizontal sections of the rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. J Neurosci Methods. 1980;3:129–49.

Chen QH, Toney GM. AT(1)-receptor blockade in the hypothalamic PVN reduces central hyperosmolality-induced renal sympathoexcitation. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2001;281:R1844–53.

Li YF, Wang W, Mayhan WG, Patel KP. Angiotensin-mediated increase in renal sympathetic nerve discharge within the PVN: Role of nitric oxide. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2006;290:R1035–43.

Cato MJ, Toney GM. Angiotensin II excites paraventricular nucleus neurons that innervate the rostral ventrolateral medulla: an in vitro patch-clamp study in brain slices. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:403–13.

Lin Y, Matsumura K, Kagiyama S, Fukuhara M, Fujii K, Iida M. Chronic administration of olmesartan attenuates the exaggerated pressor response to glutamate in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of SHR. Brain Res. 2005;1058:161–6.

Vieira AA, Colombari E, De Luca LJ, Colombari DS, De Paula PM, Menani JV. Importance of angiotensinergic mechanisms for the pressor response to l-glutamate into the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Brain Res. 2010;1322:72–80.

Ito S, Hiratsuka M, Komatsu K, Tsukamoto K, Kanmatsuse K, Sved AF. Ventrolateral medulla AT1 receptors support arterial pressure in Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Hypertension. 2003;41:744–50.

Bergamaschi CT, Silva NF, Pires JG, Campos RR, Neto HAF. Participation of 5-HT and AT1 receptors within the rostral ventrolateral medulla in the maintenance of hypertension in the goldblatt 1 kidney-1 clip model. Int J Hypertens. 2014;2014:1–6.

Ito S, Komatsu K, Tsukamoto K, Kanmatsuse K, Sved AF. Ventrolateral medulla AT1 receptors support blood pressure in hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 2002;40:552–9.

Zha YP, Wang YK, Deng Y, Zhang RW, Tan X, Yuan WJ, et al. Exercise training lowers the enhanced tonically active glutamatergic input to the rostral ventrolateral medulla in hypertensive rats. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2013;19:244–51.

Shen Z, Weng C, Zhang Z, Wang X, Yang K. Renal sympathetic denervation lowers arterial pressure in canines with obesity-induced hypertension by regulating GAD65 and AT1R expression in rostral ventrolateral medulla. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2018;40:49–57.

Dingledine R, Borges K, Bowie D, Traynelis SF. The glutamate receptor ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 1999;51:7–61.

Mayer ML. Glutamate receptor ion channels. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:282–8.

Kleiber AC, Zheng H, Sharma NM, Patel KP. Chronic AT1 receptor blockade normalizes NMDA-mediated changes in renal sympathetic nerve activity and NR1 expression within the PVN in rats with heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H1546–55.

Marques-Lopes J, Van Kempen T, Waters EM, Pickel VM, Iadecola C, Milner TA. Slow-pressor angiotensin II hypertension and concomitant dendritic NMDA receptor trafficking in estrogen receptor β-containing neurons of the mouse hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus are sex and age dependent. J Comp Neurol. 2014;522:3075–90.

Glass MJ, Wang G, Coleman CG, Chan J, Ogorodnik E, Van Kempen TA, et al. NMDA receptor plasticity in the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus contributes to the elevated blood pressure produced by angiotensin II. J Neurosci. 2015;35:9558–67.

Wang WZ, Gao L, Wang HJ, Zucker IH, Wang W. Tonic glutamatergic input in the rostral ventrolateral medulla is increased in rats with chronic heart failure. Hypertension. 2009;53:370–4.

Gao L. Superoxide mediates sympathoexcitation in heart failure: roles of angiotensin II and NAD(P)H oxidase. Circ Res. 2004;95:937–44.

Gao L, Wang W, Li Y, Schultz HD, Liu D, Cornish KG, et al. Sympathoexcitation by central ANG II: roles for AT1 receptor upregulation and NAD(P)H oxidase in RVLM. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;288:H2271–9.

Chan SH, Hsu KS, Huang CC, Wang LL, Ou CC, Chan JY. NADPH oxidase-derived superoxide anion mediates angiotensin II-Induced pressor effect via activation of p38 Mitogen-Activated protein kinase in the rostral ventrolateral medulla. Circ Res. 2005;97:772–80.

Hirooka Y. Oxidative stress in the cardiovascular center has a pivotal role in the sympathetic activation in hypertension. Hypertens Res. 2011;34:407–12.

Herzog E, Bellenchi GC, Gras C, Bernard V, Ravassard P, Bedet C, et al. The existence of a second vesicular glutamate transporter specifies subpopulations of glutamatergic neurons. J Neurosci. 2001;21:C181.

Takamori S, Malherbe P, Broger C, Jahn R. Molecular cloning and functional characterization of human vesicular glutamate transporter 3. Embo Rep. 2002;3:798–803.

Johnson J, Sherry DM, Liu X, Fremeau RT, Seal RP, Edwards RH, Copenhagen DR. Vesicular glutamate transporter 3 expression identifies glutamatergic amacrine cells in the rodent retina. J Comp Neurol. 2004;477:386–98.

Musante V, Summa M, Cunha RA, Raiteri M, Pittaluga A. Pre-synaptic glycine GlyT1 transporter–NMDA receptor interaction: relevance to NMDA autoreceptor activation in the presence of Mg2+ ions. J Neurochem. 2011;117:516–27.

Negrete-Diaz JV, Sihra TS, Delgado-Garcia JM, Rodriguez-Moreno A. Kainate receptor-mediated inhibition of glutamate release involves protein kinase a in the mouse hippocampus. J Neurophysiol. 2006;96:1829–37.

Summa M, Di Prisco S, Grilli M, Marchi M, Pittaluga A. Hippocampal AMPA autoreceptors positively coupled to NMDA autoreceptors traffic in a constitutive manner and undergo adaptative changes following enriched environment training. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:1282–90.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Chinese National Natural Science Fund (31371155).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, X., Yang, H., Song, X. et al. Central blockade of the AT1 receptor attenuates pressor effects via reduction of glutamate release and downregulation of NMDA/AMPA receptors in the rostral ventrolateral medulla of rats with stress-induced hypertension. Hypertens Res 42, 1142–1151 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0242-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-019-0242-6

Keywords:

This article is cited by

-

The brain–heart axis: effects of cardiovascular disease on the CNS and opportunities for central neuromodulation

Nature Reviews Neuroscience (2025)

-

Telmisartan mitigates behavioral and cytokine level alterations but impairs spatial working memory in a phencyclidine-induced mouse model of schizophrenia

Psychopharmacology (2025)

-

PDZD8 Dysregulation Mediates RVLM Neuronal Hyperexcitation Via Activation of Ca2+-Calpain-2 Signaling in Stress-Induced Hypertension

Molecular Neurobiology (2025)

-

Placental ischemia-upregulated angiotensin II type 1 receptor in hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus contributes to hypertension in rat

Pflügers Archiv - European Journal of Physiology (2024)

-

Angiotensin II increases the firing activity of pallidal neurons and participates in motor control in rats

Metabolic Brain Disease (2023)