Abstract

Gestational hypertension is a leading cause of both prenatal and maternal mortality and morbidity; however, there have been rather limited advances in the management of gestational hypertension in recent years. There has been evidence supporting the antihypertensive properties of crocin, but the specific mechanism is still unclear. N-Nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME) was employed to establish a rat model with a preeclampsia-like phenotype, particularly gestational hypertension. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were conducted to determine the levels of placental growth factor (PlGF) and soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFlt-1); the levels of the circulating cytokines interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α; and oxidative stress factors. Quantitative RT-PCR assays were performed to assess the transcript levels of various cytokines in the placenta, and western blot assays were carried out to evaluate the protein levels of heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) and nuclear factor-erythroid 2-like 2 (Nrf-2). Treatment with crocin reduced the blood pressure of rats with gestational hypertension, which was accompanied by suppressed circulating levels of PlGF and sFlt-1. Crocin further alleviated the inflammatory signals and oxidative stress in the serum, as well as in placental tissues, in rats with L-NAME-induced hypertension. Crocin treatment also improved pregnancy outcomes in terms of fetal survival, fetal weight, and the fetal/placental weight ratio. Finally, in hypertension elicited by L-NAME, crocin stimulated the placental Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway. Crocin alleviated inflammatory and oxidative stress in placental tissues, thereby protecting against gestational hypertension, one of the major phenotypes of preeclampsia, and activated the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gestational hypertension is defined as sustained high blood pressure (higher than 140/90 mmHg) and proteinuria after gestational week 20 and affects ~7–10% of pregnancies globally [1,2,3]. It has been regarded as one of the leading causes of prenatal and maternal mortality and morbidity, and in the United States, it accounts for approximately one-fifth of gestation-related fatalities [4, 5]. Gestational hypertension is one of the maternal complications caused by preeclampsia, in addition to pulmonary edema, eclampsia, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and thrombocytopenia [6, 7]. Accumulated evidence has implicated inflammation and mitochondrial dysfunction in the progression of gestational hypertension [8, 9]. Prior investigations have also shown an elevated incidence rate of gestational hypertension among a family with genetic mitochondrial disorders [10]. Oxidative stress, as well as the dysfunction of placental endothelial cells caused by mitochondrial dysfunction, promotes the abnormal placentation and dysregulation of vascular factors, thereby provoking gestational hypertension [11].

Nuclear factor-erythroid 2-like 2 (Nrf-2) and heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1), which are transcription factors downstream of Nrf-2, are known to participate in the cellular response to oxidative stress and stimulation of cytokines, thus protecting tissues against hypoxia and inflammation [12, 13]. Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (Keap1) binds to Nrf-2 to form heterodimers in the cytoplasm [14]. The structural properties of Keap1 are modulated by singlet oxygen or reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to the release of Nrf-2, which is subsequently translocated to the nucleus to activate several downstream genes involved in the cellular response to oxidative stress [14]. It has been reported that Nrf-2 may play a protective role in the development of gestational hypertension [15].

Crocin, a hydrophilic carotenoid pigment, is a major compound with pharmacological activities found in Crocus sativus L. (saffron) [16]. Previous reports showed that crocin rescued endothelial cell injury, thereby counteracting the progression of hypertension [17, 18]. For instance, chronic treatment with crocin dose-dependently decreased the systolic blood pressure (SBP) in rats with hypertension caused by deoxycorticosterone acetate salt while not altering the SBP of normotensive controls [19]. In addition, in a rat model of acute hypertension elicited by angiotensin II, crocin exerted beneficial cardiovascular effects, leading to improvements in SBP, heart rate, and arterial blood pressure by inhibiting the renin–angiotensin system [20]. However, the molecular mechanism responsible for the reported antihypertensive effect of crocin is still elusive. On the other hand, crocin was reported to substantially increase HO-1 expression in RAW 264.7 macrophages stimulated with lipopolysaccharide, resulting in the subsequent suppression of inducible nitric oxide (NO) synthase and anti-inflammatory responses [21]. Crocin was also found to ameliorate cerulein-induced pancreatic inflammation and oxidative stress by upregulating Nrf-2 expression [22]. Moreover, a recent report directly demonstrated that the Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway is a target of crocin in a rat model of ulcerative colitis [23].

Based on the reported role of Nrf-2/HO-1 in gestational hypertension and the antihypertensive effect of crocin, as well as its ability to target the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway, we hypothesized that crocin was potentially able to attenuate gestational hypertension. We therefore aimed to test this hypothesis using an N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester (L-NAME)-induced rat model with preeclampsia-like symptoms, particularly gestational hypertension.

Materials and methods

Animals

Female Sprague-Dawley rats (~10 weeks old, 220–250 g) were housed with a virus/antigen-free ventilation system under constant humidity and temperature. The rats were allowed ad libitum access to water and food. The Animal Use Committee of Quanzhou First Hospital Affiliated to Fujian Medical University approved the use of all the experimental animals.

L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rat model with gestational hypertension

The day after mating, the vaginal plug was checked at 6:00 a.m., the appearance of which indicated the beginning of gestation, termed gestation day (GD) 1. Pregnant female rats were assigned randomly into five groups (18 rats each). L-NAME (50 mg/kg/day), obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, USA) and dissolved in sterile saline, was administered via oral gavage to pregnant females between GD 14 and 19 to establish preeclampsia with gestational hypertension, according to previously established methods [24, 25]. Crocin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in sterile saline and administered continuously to the rats via oral gavage between GD 10 and GD 19 at doses of 50, 100, and 200 mg/kg/day. Samples of serum and placental tissues of the pregnant rats were collected on GD 20.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Assessments of serum antibody and cytokine levels were achieved using rat-specific ELISA kits (Chondrex) following the manufacturer’s guidance. Levels of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase (sFlt-1) and placental growth factor (PlGF); circulating levels of the cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α; and the oxidative stress factors H2O2, MDA, GSH, GPx, catalase, and SOD were examined using rat-specific Ready-Set-Go ELISA Kits (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s protocols.

Measurement of blood pressure and urine protein

A BP-6 noninvasive blood-pressure detector (Bio-Equip, Shanghai, China) was employed to measure the blood pressure of pregnant female rats through tail cuffing at GD 12, 16, and 20. The urine of pregnant rats was sampled by spot collection at 8 a.m., 4 p.m., and 10 p.m. on GDs 12, 16, and 20 for the quantification of urine proteins.

Quantitative real-time PCR

TRIzol reagent purchased from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA, USA) was employed to prepare the total RNA from trophoblasts of experimental and control rats. Transcription Kits (Fermentas, St. Leon-Rot, Germany) were then utilized to reverse transcribe 1 μg of RNA from each tissue into cDNAs. One microgram of cDNA and 0.2 μM of each pair of primers were added to the 20-μl real-time reaction and run on a QuantStudio-1 Real-Time PCR System. GAPDH was included as an endogenous control. The primers used were as follows: IL-6 sense 5′-TCT ATA CCA CTT CAC AAG TCG-3′, anti-sense 5′-GAA TTG CCA TTG CAC AAC TCT-3′; TNF-α sense 5′-CCT GTA GCC CAC GTC GTA-3′, anti-sense 5′-GGG AGT AGA CAA GGT ACA ACC-3′; IL-1β sense 5′-CTG TGA CTC ATG GGA TGA TGA-3′, anti-sense 5′-CGG AGC CTG TAG TGC AGT-3′; and GAPDH sense 5′-TGG CCT TCC GTG TTC CTA-3′, anti-sense 5′-GAG TTG CTG AAG TCG-3′.

Western blot

Placental cells were digested and resuspended in ice-cold nuclear fractionation buffer (20-mM HEPES, 10-mM KCl, 2-mM MgCl2, 1-mM EDTA, pH 7.4), passed through a 27 gauge needle 8–12 times, and incubated on ice for 20 min. The cell lysate was then centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 5 min. The pellet was collected for the nuclear fraction, and the supernatant was collected for the cytosolic fraction. All the samples prepared in the loading buffer were boiled for 10 min. The denatured proteins were separated via 10% SDS-PAGE, and NC membranes (Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) were used to transfer the resolved proteins. Then, anti-Nrf-2, anti-HO-1, anti-Lamin B1, and anti-GAPDH antibodies (Centennial, CO, USA) were used separately to incubate the membranes overnight at 4 °C. Secondary antibodies (Abcam, Shanghai, China) were then applied to membranes after washing with PBST for 1 h at 37 °C.

Statistical analysis

All data, with at least three repeats, were verified as normally distributed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test and then analyzed using a two-tailed Student’s t test and presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD). P values < 0.05 were regarded as indications of statistical significance. The calculation and analysis were conducted using SPSS software (Ver. 16.0, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Crocin attenuates SBP and 24-h proteinuria in preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension

To examine the antihypertensive property of crocin in preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension induced by L-NAME, we treated the rats with various doses of crocin and measured their SBP as well as 24-h proteinuria. As presented in Fig. 1A, L-NAME treatment leds to abnormal hypertension in pregnant females compared with control rats, and treatment with crocin significantly reduced SBP in a dose-dependent manner. Since the most remarkable antihypertensive effect was observed with 200-mg/kg/day crocin, this dose was used for the rest of the investigation. Similarly, L-NAME increased the 24-h proteinuria, and 200-mg/kg/day crocin reduced the urine protein most dramatically (Fig. 1B).

Crocin attenuates systolic blood pressure (SBP) and 24-h proteinuria in L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension. A The SBP of each indicated group was measured noninvasively using the tail-cuff method at GDs 12, 16, and 20. B The 24-h proteinuria in each group was detected using CBB kits at GDs 12, 16, and 20. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 12 in each group). **p < 0.01 compared to the control; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared to L-NAME

Crocin restores the balance of sFlt-1/PlGF in the serum and placenta of L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension

PlGF and sFlt-1 are both angiogenesis-related factors that participate in the regulation of angiogenesis, arteriogenesis, and vasculogenesis, whose balance is crucial for angiogenic homeostasis during placental development. Abnormal sFlt-1 upregulation and PlGF downregulation during pregnancy cause multiple complications, including hypertension. To assess whether crocin treatment could ameliorate the abnormal alterations in PlGF and sFlt-1, ELISA was conducted. Treatment with 200-mg/kg/day crocin reduced the circulating level of sFlt-1 (Fig. 2A) while elevating the circulating level of PlGF (Fig. 2B) in hypertensive rats, thus significantly lowering the serum sFlt-1/PlGF ratio (Fig. 2C). To examine the levels of placental PlGF and sFlt-1, ELISA was performed in rat placental tissues. Treatment with 200-mg/kg/day crocin reduced the sFlt-1 placental protein level (Fig. 2D) but increased the placental protein level of PlGF (Fig. 2E) in model rats, resulting in a markedly decreased sFlt-1/PlGF ratio in the placenta of hypertensive rats (Fig. 2F).

Crocin restores the balance of sFlt-1/PlGF in the serum and placenta of L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension. Serum levels of sFlt-1 (A) and PlGF (B) and their ratio (C) were measured by ELISA on GD 20. Placental levels of sFlt-1 (D) and PlGF (E) and their ratio (F) were measured by ELISA on GD 20. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 12 in each group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to the control; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared to L-NAME

Crocin alleviates serum and placental inflammation in L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension

The levels of the cytokines IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the circulation as well as placental tissues were measured using ELISA and quantitative RT-PCR to evaluate the inflammatory responses in the model rats. As shown in Fig. 3A–C, L-NAME upregulated the circulating levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α, suggesting that L-NAME induced inflammation in hypertensive rats. In contrast, 200-mg/kg/day crocin administration reduced the levels of all three cytokines, indicating that crocin alleviated L-NAME-induced inflammation. As shown in Fig. 3D–F, the mRNA levels of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α in the placental tissues were assessed using quantitative RT-PCR assays, where 200-mg/kg/day crocin administration resulted in a dramatic downregulation of all three cytokines.

Crocin alleviates serum and placental inflammation in L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension. Serum levels of IL-6 (A), TNF-α (B), and IL-1β (C) were measured by ELISA on GD 20. D–F Placental mRNA levels of IL-6 (A), TNF-α (B), and IL-1β (C) were measured by qRT-PCR on GD 20. The relative mRNA level was analyzed by the 2−ΔΔct method and normalized to the control group. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 12 in each group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to the control; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared to L-NAME

Crocin alleviates placental oxidative stress in L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension

Accumulated evidence has shown the antioxidative properties of crocin. To demonstrate the effect of crocin on oxidative stress in the placenta of model rats, we conducted ELISA. The MDA and H2O2 levels in the placental tissues were lower in rats treated with 200-mg/kg/day crocin (Fig. 4A, B), whereas the placental levels of GPx, SOD, catalase, and GSH were all elevated (Fig. 4C–F). These findings showed that crocin exerted antioxidative effects in the placenta of gestational hypertensive rats.

Crocin alleviates placental oxidative stress in L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension. The activities of MDA (A), H2O2 (B), GSH (C), SOD (D), GPx (E), and catalase (F) in the placenta were measured by ELISA on GD 20. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 12 in each group). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared to the control; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared to L-NAME

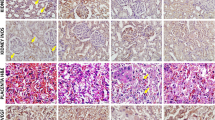

Crocin improves pregnancy outcomes of L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension

Next, the six remaining pregnant rats were allowed to give birth, followed by evaluation of fetal survival, fetal weight, placental weight, and the fetal/placental weight ratio to address the effect of crocin on pregnancy outcomes. As shown in Fig. 5A, B, L-NAME exposure imposed detrimental effects on pregnancy outcomes, namely, reduced fetal survival rate and fetal weight, in comparison with the controls, whereas crocin ameliorated the effects of L-NAME and improved those parameters. On the other hand, although no significant change was seen in placental weight in the three experimental groups (Fig. 5C), the fetus/placenta weight ratio was significantly improved by comparing the L-NAME group with the L-NAME + crocin group (Fig. 5D), suggesting that crocin administration alleviated this effect.

Effects of crocin on pregnancy outcomes in pregnant rats exposed to L-NAME. A Fetal survival, B fetal weight, C placental weight, and D the fetal/placental weight ratio were evaluated at full term after delivery. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 6 in each group). *p < 0.05 compared to control; #p < 0.05 compared to L-NAME

Crocin activates the placental Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway in L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension

Recent investigations have shed light on the potential role of Nrf-2/HO-1 in the pathogenesis of L-NAME-induced gestational hypertension. To determine whether crocin is capable of regulating Nrf-2 and HO-1 expression, we performed western blot assays. As shown in Fig. 6A, B, the protein levels of Nrf-2, both nuclear and total, were elevated when treated with 200-mg/kg/day crocin. Furthermore, the protein level of HO-1 was also dramatically upregulated by crocin treatment (Fig. 6A). ELISA was carried out to determine the placental levels of Nrf-2 and HO-1 in model rats as well. Consistently, 200-mg/kg/day crocin administration increased the abundance of Nrf-2 and HO-1 in the placenta of hypertensive rats (Fig. 6C, D). These results suggested that in addition to protecting against L-NAME-induced gestational hypertension in the preeclampsia rat model, crocin was also able to activate the Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway.

Crocin activates the placental Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway in L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension. A, B The contents of total Nrf-2, nuclear Nrf-2, and HO-1 were determined by the western blot analysis on GD 20. C, D Placental levels of Nrf-2 and HO-1 were measured by ELISA on GD 20. Values are the mean ± SD (n = 12 in each group). *p < 0.05 compared to the control; #p < 0.05, ##p < 0.01 compared to L-NAME

Discussion

Gestational hypertension is still clinically challenging despite a number of recent breakthroughs in the management of gestational complications [26, 27]. In Europe, the incidence of gestational hypertension was estimated to be ~3%, and in the United States, gestational hypertension is ranked as one of the top causes of maternal fatalities [28]. During gestation, the maternal hemodynamic and cardiovascular changes are fairly drastic: the high maternal plasma volume mandates alterations in heart rate, cardiac output, blood pressure, and vascular resistance to support the growth of the fetus [29]. Dysregulation of critical factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), prostacyclin, and NO during this process could give rise to gestational hypertension [30, 31].

Previous investigations have roughly described the two stages in the pathogenesis of gestational hypertension [32]. Abnormal placentation and decreased placental perfusion due to inflammation and oxidative stress take place during the first stage. The second stage is characterized by dysregulated circulating VEGFs, including sFlt-1, PlGF and soluble endoglin, and consequently systemic vascular dysfunction. Given the pathological progression of gestational hypertension, gestational inflammation and oxidative stress are critical factors. The reaction among NO, ROS, and superoxide (O2−) reportedly causes accumulated peroxynitrite (ONOO−) in the placenta and disturbs normal trophoblast functions [30]. The reduced aggregation capacity of trophoblasts results in placental ischemia and abnormal placentation, thereby inducing chronic inflammatory reactions [33]. Randomized controlled trials are widely adopted clinically for blood-pressure management, and there have been rather conflicting results. The identification of novel treatment strategies to tackle inflammation and oxidative stress to ameliorate gestational hypertension at an early stage is urgently needed.

In the current study, we showed that crocin reduced the blood pressure and urine proteins of rats with preeclampsia-related gestational hypertension induced by L-NAME. We also found that crocin exerted anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects in hypertensive rats, supporting the potential of crocin to protect against preeclampsia-related gestational hypertension. Previous studies have demonstrated the effect of plant extracts, including crocin, in alleviating oxidative stress and hypertensive symptoms [17, 19, 20, 34, 35]. However, the mechanistic details underlying the effects of crocin on the progression of hypertension are largely unclear. In our study, we discovered the anti-inflammatory and antioxidative effects of crocin in an L-NAME-induced preeclampsia-related hypertensive rat model. In addition, our study is also the first to report that crocin alleviated preeclampsia-related gestational hypertension and activated the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway.

Previous evidence has demonstrated the contribution of oxidative stress to placental injuries, and ROS-induced trophoblast dysfunction during gestational hypertension has attracted increasing attention. Exploration of means to lower ROS levels and to inhibit the inflammatory response is of great significance for preventing and treating gestational hypertension. Nrf-2 is a transcription factor involved in the cellular response to oxidative stress. Keap1 reportedly binds to Nrf-2 to form heterodimers in the cytoplasm. The structural features of Keap1 are modulated by singlet oxygen or ROS, leading to the release of Nrf-2 and its translocation to the nucleus, followed by the activation of various downstream genes responding to oxidative stress [36]. Accumulated evidence has revealed the critical function of Nrf-2 in the pathogenesis of gestational hypertension. As an example, it was reported that detoxification enzymes are increased via the Nrf-2/HO-1 pathway to reduce plasma ROS levels and maintain the normal activities of the placenta [37]. In addition, low Nrf-2 activation and low HO-1 expression in the placenta were also reported to be involved in preeclampsia [38]. The current study is the first demonstration of crocin upregulating the Nrf-2 level and thus activating the Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway while simultaneously relieving the symptoms of preeclampsia-related gestational hypertension.

In summary, we hereby showed that crocin alleviated inflammation and oxidative stress in the placenta of hypertensive rats to protect against preeclampsia-related gestational hypertension and activated the Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Crocin treatment lowered blood pressure and urine protein and alleviated serum and placental inflammation as well as oxidative stress in preeclampsia rats with gestational hypertension, and reduced the circulating levels of PlGF and sFlt-1. Importantly, crocin also improved pregnancy outcomes in terms of fetal survival, fetal weight, and the fetal/placental weight ratio. Mechanistically, crocin activated the Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway in the placenta, which likely contributed to the aforementioned beneficial effects in the L-NAME-induced preeclampsia rat model with gestational hypertension. These results might pave the way for novel preventive strategies employing crocin to combat gestational hypertension. Nevertheless, it should be noted that although crocin has been tested in some clinical trials of several human diseases [39,40,41], there has been no clinical study employing crocin to combat pregnancy hypertensive disorders. Therefore, extra caution should be taken when applying crocin to pregnant women. In addition, in the current study, crocin treatment began several days before L-NAME administration, and it would be worth investigating whether crocin has a similar effect when administered after the onset of L-NAME-induced hypertension in future studies.

References

WHO Recommendations for Prevention and Treatment of Pre-Eclampsia and Eclampsia. Geneva; 2011.

Sharf M, Eibschitz I, Hakim M, Degani S, Rosner B. Is Serum Free Estriol Measurement Essential in the Management of Hypertensive Disorders during Pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gyn R B. 1984;17:365–75.

Visintin C, Mugglestone MA, Almerie MQ, Nherera LM, James D, Walkinshaw S, et al. Guidelines Management of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy: summary oif NICE guidance. Brit Med J. 2010;341.

Savitz DA, Danilack VA, Engel SM, Elston B, Lipkind HS. Descriptive epidemiology of chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension, and preeclampsia in New York State, 1995–2004. Matern Child Health J. 2014;18:829–38.

Schneider S, Freerksen N, Maul H, Roehrig S, Fischer B, Hoeft B. Risk groups and maternal-neonatal complications of preeclampsia–current results from the national German Perinatal Quality Registry. J Perinat Med. 2011;39:257–65.

Larcan A, Lambert H, Laprevote MC, Alexandre P. Disseminated intravascular coagulation and acute renal failure in the field of obstetrics. Bibl Anat. 1975;13:347–50.

Rattray DD, O’Connell CM, Baskett TF. Acute disseminated intravascular coagulation in obstetrics: a tertiary centre population review (1980 to 2009). J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2012;34:341–7.

Draganovic D, Lucic N, Jojic D. Oxidative Stress Marker and Pregnancy Induced Hypertension. Med Arch. 2016;70:437–40.

Harmon AC, Cornelius DC, Amaral LM, Faulkner JL, Cunningham MW Jr, Wallace K, et al. The role of inflammation in the pathology of preeclampsia. Clin Sci (Lond). 2016;130:409–19.

Matsubara S, Minakami H, Sato I, Saito T. Decrease in cytochrome c oxidase activity detected cytochemically in the placental trophoblast of patients with pre-eclampsia. Placenta. 1997;18:255–9.

van der Graaf AM, Wiegman MJ, Plosch T, Zeeman GG, van Buiten A, Henning RH, et al. Endothelium-dependent relaxation and angiotensin II sensitivity in experimental preeclampsia. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e79884.

Kensler TW, Wakabayashi N, Biswal S. Cell survival responses to environmental stresses via the Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway. Annu Rev Pharm Toxicol. 2007;47:89–116.

Kang SJ, You A, Kwak MK. Suppression of Nrf2 signaling by angiotensin II in murine renal epithelial cells. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34:829–36.

Itoh K, Mimura J, Yamamoto M. Discovery of the negative regulator of Nrf2, Keap1: a historical overview. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2010;13:1665–78.

Kweider N, Huppertz B, Kadyrov M, Rath W, Pufe T, Wruck CJ. A possible protective role of Nrf2 in preeclampsia. Ann Anat. 2014;196:268–77.

Rahaiee S, Moini S, Hashemi M, Shojaosadati SA. Evaluation of antioxidant activities of bioactive compounds and various extracts obtained from saffron (Crocus sativus L.): a review. J Food Sci Technol. 2015;52:1881–8.

Imenshahidi M, Hosseinzadeh H, Javadpour Y. Hypotensive effect of aqueous saffron extract (Crocus sativus L.) and its constituents, safranal and crocin, in normotensive and hypertensive rats. Phytother Res. 2010;24:990–4.

Imenshahidi M, Razavi BM, Faal A, Gholampoor A, Mousavi SM, Hosseinzadeh H. The Effect of Chronic Administration of Saffron (Crocus sativus) Stigma Aqueous Extract on Systolic Blood Pressure in Rats. Jundishapur J Nat Pharm Prod. 2013;8:175–9.

Imenshahidi M, Razavi BM, Faal A, Gholampoor A, Mousavi SM, Hosseinzadeh H. Effects of chronic crocin treatment on desoxycorticosterone acetate (doca)-salt hypertensive rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2014;17:9–13.

Shafei MN, Faramarzi A, Khajavi Rad A, Anaeigoudari A. Crocin prevents acute angiotensin II-induced hypertension in anesthetized rats. Avicenna J Phytomed. 2017;7:345–52.

Kim JH, Park GY, Bang SY, Park SY, Bae SK, Kim Y. Crocin suppresses LPS-stimulated expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase by upregulation of heme oxygenase-1 via calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase 4. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:728709.

Godugu C, Pasari LP, Khurana A, Anchi P, Saifi MA, Bansod SP, et al. Crocin, an active constituent of Crocus sativus ameliorates cerulein induced pancreatic inflammation and oxidative stress. Phytother Res. 2020;34:825–35.

Khodir AE, Said E, Atif H, ElKashef HA, Salem HA. Targeting Nrf2/HO-1 signaling by crocin: Role in attenuation of AA-induced ulcerative colitis in rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;110:389–99.

Kemse NG, Kale AA, Joshi SR. A combined supplementation of omega-3 fatty acids and micronutrients (folic acid, vitamin B12) reduces oxidative stress markers in a rat model of pregnancy induced hypertension. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e111902.

Wang Y, Huang M, Yang X, Yang Z, Li L, Mei J. Supplementing punicalagin reduces oxidative stress markers and restores angiogenic balance in a rat model of pregnancy-induced hypertension. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2018;22:409–17.

Armaly Z, Zaher M, Knaneh S, Abassi Z. [Preeclampsia: Pathogenesis and Mechanisms Based Therapeutic Approaches]. Harefuah. 2019;158:742–7.

Moradi MT, Rahimi Z, Vaisi-Raygani A. New insight into the role of long non-coding RNAs in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2019;38:41–51.

Lv X, Li X, Dai X, Liu M, Wu C, Song W, et al. Investigation heme oxygenase-1 polymorphism with the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2020;42:167–70.

Kara AE, Guney G, Tokmak A, Ozaksit G. The role of inflammatory markers hs-CRP, sialic acid, and IL-6 in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2019;30:29–33.

Matsubara K, Higaki T, Matsubara Y, Nawa A. Nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16:4600–14.

Matsubara K, Matsubara Y, Hyodo S, Katayama T, Ito M. Role of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36:239–47.

Sircar M, Thadhani R, Karumanchi SA. Pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2015;24:131–8.

Williams PJ, Searle RF, Robson SC, Innes BA, Bulmer JN. Decidual leucocyte populations in early to late gestation normal human pregnancy. J Reprod Immunol. 2009;82:24–31.

Chen S, Sun P, Zhao X, Yi R, Qian J, Shi Y, et al. Gardenia jasminoides has therapeutic effects on LNNAinduced hypertension in vivo. Mol Med Rep. 2017;15:4360–73.

Raji M, Chen Z. Effects of abiotic elicitors on the production of bioactive flavonols in Emilia sonchifolia. STEMedicine. 2020;1:e33.

Loboda A, Damulewicz M, Pyza E, Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. Role of Nrf2/HO-1 system in development, oxidative stress response and diseases: an evolutionarily conserved mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2016;73:3221–47.

Ding C, Zou Q, Wu Y, Lu J, Qian C, Li H, et al. EGF released from human placental mesenchymal stem cells improves premature ovarian insufficiency via NRF2/HO-1 activation. Aging (Albany NY). 2020;12:2992–3009.

Chigusa Y, Tatsumi K, Kondoh E, Fujita K, Nishimura F, Mogami H, et al. Decreased lectin-like oxidized LDL receptor 1 (LOX-1) and low Nrf2 activation in placenta are involved in preeclampsia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:E1862–70.

Talaei A, Hassanpour Moghadam M, Sajadi Tabassi SA, Mohajeri SA. Crocin, the main active saffron constituent, as an adjunctive treatment in major depressive disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot clinical trial. J Affect Disord. 2015;174:51–6.

Sepahi S, Mohajeri SA, Hosseini SM, Khodaverdi E, Shoeibi N, Namdari M, et al. Effects of Crocin on Diabetic Maculopathy: A Placebo-Controlled Randomized Clinical Trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;190:89–98.

Ghaderi A, Rasouli-Azad M, Vahed N, Banafshe HR, Soleimani A, Omidi A, et al. Clinical and metabolic responses to crocin in patients under methadone maintenance treatment: A randomized clinical trial. Phytother Res. 2019;33:2714–25.

Funding

The study was supported by the Quanzhou Science and Technology Plan Project (2020N022s).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Huang, J., Lv, Y. et al. Crocin exhibits an antihypertensive effect in a rat model of gestational hypertension and activates the Nrf-2/HO-1 signaling pathway. Hypertens Res 44, 642–650 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00609-7

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-00609-7

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Crocin's role in modulating MMP2/TIMP1 and mitigating hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension in mice

Scientific Reports (2024)

-

Preeclampsia up to date—What’s going on?

Hypertension Research (2023)