Abstract

Coronary flow velocity (CFV) is reduced in pathologic cardiac hypertrophy. This functional reduction is linked to adverse cardiac remodeling, hypertension and fibrosis, and angiotensin II (AngII) is a key molecular player. Angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) are known to attenuate adverse cardiac remodeling and fibrosis following increased afterload, while the mechanism by which these drugs offer clinical benefits and regulate hemodynamics remains unknown. To establish a direct connection between coronary flow changes and angiotensin-induced hypertension, we used a Doppler echocardiographic method in two distinct disease models. First, we performed serial echocardiography to visualize coronary flow and assess heart function in patients newly diagnosed with hypertension and currently on ARBs or calcium channel blockers (CCBs). CFV improved significantly in the hypertensive patients after 12 weeks of ARB treatment but not in those treated with CCBs. Second, using murine models of pressure overload, including Ang II infusion and aortic banding, we mimicked the clinical conditions of Ang II- and mechanical stress-induced hypertension, respectively. Both Ang II infusion and aortic banding increased the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship and cardiac fibrosis, but interestingly, only Ang II infusion resulted in a significant reduction in CFV and corresponding activation of pressure-sensitive proteins, including connective tissue growth factor, hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. These data support the existence of a molecular and functional link between AngII-induced hemodynamic remodeling and alterations in coronary vasculature, which, in part, can explain the clinical benefit of ARB treatment in hypertensive patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Coronary flow velocity (CFV) is considered an important parameter for the assessment of coronary circulation and the overall function of the microvasculature [1]. Prior reports have suggested that coronary microcirculation is disrupted in hypertensive patients [2]. In systemic chronic hypertension, the structure and function of the microvasculature is altered, leading to enhanced vasoconstriction or reduced vasodilator responses [2, 3], which cause fibrosis over time [4]. With regard to coronary flow perturbations in hypertension, given the likelihood of an increase in the wall-to-lumen ratio, rarefaction of capillaries can occur, leading to an attenuation of coronary flow to the myocardium, especially in diastole [2].

Various antihypertensive agents, including pharmacological antagonists such as angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), offer benefits to patients and have been demonstrated to ameliorate the pressure overload associated with hypertension, primarily by modulating systemic blood pressure [2, 5]. However, questions remain around the actual mechanics of ARBs and calcium channel blockers (CCBs) in cardiovascular disease, as they are used with patients diagnosed with cardiac hypertension or hypertrophy [4, 5]. It should be noted here that coronary flow is affected not only by the increase in intracardiac pressure following pressure overload but also more prominently by angiotensin II-associated cardiac molecular remodeling [4, 6]. We hypothesized that ARBs directly alter coronary microcirculation by initiating angiotensin II-mediated molecular changes in the vasculature, while CCBs exert their clinical effect due to secondary neurohormonal factors [5, 7, 8]. From a clinical perspective, hypertension in humans is associated with marked changes in systemic neurohormonal factors, volume status and systemic vascular resistance that accompany pressure overload [9]. To determine whether changes in coronary flow parameters are specifically and primarily linked to neurohormonal factors or if they are pure hemodynamic changes that accompany hypertension, we compared CFV between hypertensive patients treated with ARBs and those on CCBs. In addition, to determine whether the change in CFV observed with hypertension was due to the influence of systemic factors or hemodynamic parameters, we utilized a model of aortic banding to represent hemodynamic pressure overload and a model of angiotensin II infusion to mimic neurohormonal factors [9, 10]. The goal of our study was to establish a mechanistic link between ARB-like therapeutics and alterations in microvasculature that often underlie chronic pressure overload conditions.

Methods

Subjects and study protocol

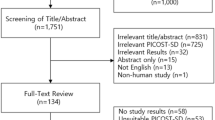

Between June and December 2015, in this longitudinal, prospective study, we prospectively enrolled newly diagnosed hypertensive patients who visited Chi-Mei Medical Center as outpatients. Essential hypertension was determined by readings of high office blood pressure (BP) on more than two occasions (systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg). After excluding individuals with coronary artery disease (documented by either coronary angiography or stress tests), diabetes mellitus, structural heart disease, atrial fibrillation or poor image quality, patients (n = 70) were consecutively enrolled and randomly separated into two groups. Thirty-five patients received a CCB, nifedipine 30 mg; the other 35 patients received an ARB, telmisartan 40 mg, for 3 months. The doses of CCB and ARB used were chosen according to previous evidence [11, 12] and were also adjusted by primary care physicians to achieve optimal blood pressure per standard practice. In addition, 10 age- and sex-matched normotensive subjects were enrolled to allow comparisons with healthy controls. All patients provided medical histories, underwent physical examinations, and provided blood samples during the first visit. They also underwent echocardiography and CFV measurements prior to and 12 weeks after antihypertensive therapies. Informed consent was obtained from each patient, and the study was conducted according to the recommendations of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki on Biomedical Research involving human subjects and was approved by the local Ethics Committee (IRB: 10312-002). Written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Echocardiography and CFV measurement in clinical study

Standard echocardiography was performed (iE33, Philips, CA, USA) with a 3.5-MHz multiphase-array probe in accordance with the recommendations of the American Society of Echocardiography [13]. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured using the biplane Simpson’s method. In addition, LV diastolic function-associated parameters, including the transmitral and tricuspid early filling velocity (E) to atrial velocity (A) ratio and tissue Doppler imaging, were obtained from the apical four-chamber view. Peak systolic annular velocity (S′) and early (e′) and late (a′) annular diastolic velocities were measured. In addition, CFV was examined before and three months after the initiation of antihypertensive therapies. The method of CFV measurement has been described previously [14]. In brief, the velocity scale of color Doppler was set to 0.24 m/s but was actively changed to provide optimal images (Fig. 1A). With the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, the mid- and distal left anterior descending artery could be seen from the modified parasternal short-axis, focusing on the anterior interventricular sulcus. The coronary artery flow velocity waveform appears as a complex of small waves in systole and a large trapezoidal wave in diastole. In addition to CFV, the average diastolic mean velocity was measured at baseline and 3 months after antihypertensive therapies.

The illustrations and demostrations of coronary flow measurements in both human and mouse hearts. A Illustration of flow detection in the middle left coronary artery in hypertensive patients. B Detection of flow at the septal coronary artery in aortic-banded mice. C An example of the changes in coronary flow velocities under 1% and 2.5% isoflurane (hyperemia) in mice at baseline, post aortic banding and debanding (n = 10–12 for each group)

Animal model of aortic banding

Eighteen 8- to 10-week-old male C57BL/6 mice (BW ~ 25 g) were randomized into three groups: sham (n = 5), aortic banding (n = 8), and initial aortic banding and subsequent debanding surgeries one week postbanding (n = 5). Sham-operated animals underwent an initial left side parasternal incision that involved handling of the aorta without constriction. The method of aortic banding and debanding was described in detail previously [10, 15]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and intubated to maintain adequate ventilation. The ascending aorta was exposed via left side parasternal incision, and a 26G needle was secured against the ascending aorta and tightly banded using an 8.0 silk suture. One week after the operation, the chest cavity was reopened in a subset of mice (from the banded cohort), and the ligature was removed. All procedures in mice were performed in accordance with American Veterinary Medical Association guidelines and approved Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees protocols (Code: 104120112).

Angiotensin II micropump surgery

An Alzet osmotic micropump (model 2004, Durect Corporation, Cupertino, USA) was subcutaneously implanted as previously described [16]. Each pump delivered 1000 ng/kg/min Ang II (Millipore-Sigma, ME, USA) dissolved in saline at a rate of 0.25 μL/h over 28 days.

Blood pressure measurement in mice

Blood pressure was monitored by noninvasive tail-cuff plethysmography at baseline and 6 and 28 days post micropump implantation using a noninvasive tail-cuff blood pressure analyzer (CODA System, Kent Scientific, Torrington, CT) [17]. Briefly, mice were trained for a period of time over 3–4 days and placed on a prewarmed platform for 10 min before assessment of blood pressure each day. Ten cycle measurements were collected on the final day of reading, and the mean was calculated for both systolic and diastolic blood pressure measurements. Blood pressure assessments were performed by the same person throughout the training period and for the final readings.

Pressure volume loop measurement in mice

As described previously [18], mice were anesthetized, and a pressure probe catheter (AD Instruments, Colorado Springs, CO) was retrogradely inserted in the LV from the right carotid artery. Using LabChart 8 (AD Instruments), the hemodynamic parameters and pressure-volume loops were recorded and measured [10, 18].

Echocardiography and CFR measurement in mice

Using a VisualSonics Vevo 2100 machine and MS550D probe with a center frequency of 40 MHz, cardiac imaging was performed in mice on Day 3, Day 7, and Day 14 post-aortic banding or angiotensin II pump implantation. The method of coronary flow imaging acquisition of mice was addressed previously [19]. Briefly, the mice were under 1% Isoflurane anesthesia. Initially, the probe was adjusted in the position for the parasternal long axis view and then rotated clockwise slightly to represent a full-length longitudinal view of the septal coronary artery. Under the color Doppler window, a pulsed wave was applied to measure the CFV at the highest possible frame rate (>100 frames/s) (Fig. 1B). Under 2.5% isoflurane, CFV was also obtained in a hyperemic status and consequently used for the calculation of CFR (Fig. 1C).

Immunohistochemistry

Four weeks post-aortic banding or AngII pump implantation, the mice were euthanized following the last measurement after noninvasive echocardiography, and the hearts were harvested for histological assessment. All cardiac tissue was fixed with buffered 10% formalin solution. Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue slides were prepared for Masson trichrome staining. Histologic quantification of myocardial fibrosis was performed using ImageJ (v1. 6).

Western blot

Tissue sections from the LV were lysed in lysis buffer (Millipore Billerica MA, USA). Western blots were probed for antibodies against connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) (Abcam), hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) (Abcam), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (Abcam).

Statistics

All values are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using one-way ANOVA and Student’s unpaired t test using GraphPad Prism (Version 5.03), with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant. Using regression analyses, we also examined the association of conventional and advanced echocardiographic measures with increasing tertiles of each BP measure. In addition to unadjusted models, we performed regression analyses adjusting for age and sex. The intra- and interobserver reliabilities of the CFV measurements were assessed on the basis of 20 randomly selected subjects and 10 mice via linear regression of the interclass correlation coefficients.

Results

In hypertensive patients, CFV improved following 12 weeks of treatment with ARBs but not CCBs

There were no significant differences in baseline clinical or echocardiographic characteristics in the control, CCB or ARB groups except for a lower baseline blood pressure in the control group (Table 1). After treatment, SBP and DBP were similar between the CCB and ARB treatment groups. Despite no specific differences in LVMI and LVEF, among the two treatment groups, Doppler-derived diastolic function (Control vs. CCB vs. ARB: 10.3 ± 2.8 cm/s vs. 8.2 ± 1.8 cm/s vs. 8.4 ± 2.7 cm/s, p = 0.01) and CFV (Control vs. CCB vs. ARB: 40.1 ± 8.7 cm/s vs. 28.5 ± 7.5 cm/s vs. 26.4 ± 6.5 cm/s, p = 0.01) declined appreciably in hypertensive patients treated with CCBs or ARBs compared with the control. Notably, the average CFV in hypertensive patients improved significantly after 12 weeks of ARB treatment; conversely, however, changes in CFV were not detected in patients treated with CCBs (ARBs vs. CCB: 38.1 ± 7.8 vs. 33.0 ± 8.2 cm/s, p = 0.003) (Table 2).

In a murine hypertension model, angiotensin II infusion but not aortic banding led to attenuation of CFV

While no difference in heart rate and contractile function as measured by fractional shortening (FS%) was observed (Supplementary Fig. S1A) between the three groups (sham, banded, and banded-debanded), LV wall thickness and chamber dimensions were found to increase in the banded cohort specifically and returned to baseline following relief of hemodynamic stress by removal of the ligature or debanding (Supplementary Fig. S1B–D). CFV at rest did not change even with acute systolic pressure overload or following debanding (Fig. 2A) only when, in the setting of hyperemia, the CFR decreased during aortic banding and returned to normal with relief of hemodynamic stress (Fig. 2B, C).

A Coronary flow velocity (CFV) at rest failed to reflect the influence of aortic banding and debanding, while B CFV at hyperemia and C coronary flow reserve (CFR) declined significantly post-aortic banding in mice and was relatively restored postdebanding. Both CFV at rest D and E hyperemia decreased significantly after angiotensin II infusion for 4 weeks. F There was also a nonspecific decline in CFR (n = 10–12 for each group)

As shown in Supplementary figs. S2 and S3, after Ang II infusion, both SBP and DBP increased significantly in the mouse model of Ang II infusion (Supplementary Fig. S2). While there was an increase in LV wall thickness, there was no significant change in heart rate, LV dimensions or fractional shortening (Supplementary Fig. S3). In contrast to the aortic banding model, interestingly, CFV declined in both rest and hyperemic status with Ang II infusion (Fig. 2D–F).

Pressure–volume loop analysis in mice post-aortic banding or angiotensin II treatment

To observe the effect of angiotensin on hemodynamic parameters, we performed a pressure volume loop study 4 weeks after aortic banding or Ang II micropump implantation. Despite similar left ventricular volumes between groups, there were significant increases in left ventricular pressures at the end systolic and diastolic phases in both aortic-banded and Ang II-treated mice compared with sham mice (Fig. 3A, B). While elastance (Ea) was not significantly changed, we found an increase in the exponential decay of ventricular pressure during the isovolumic relaxation phase (tau) in mice (Fig. 3A, B). To determine the preload-independent parameters, the abdominal inferior vena cava was transiently compressed/occluded during the pressure volume loop analysis. Although the slopes of the end-diastolic pressure volume relationship curves were not significantly different between the groups, the slope of the end-systolic pressure volume relationship was steeper after aortic banding or angiotensin II treatment (Fig. 3A, B).

A Illustration of pressure volume loop recordings in sham mice (left) and mice after aortic banding for 4 weeks (right). The left ventricular volumes and pressures at the end systolic and diastolic phases. Arterial elastance (Ea) and exponential decay of ventricular pressure during isovolumic relaxation (tau). The end-diastolic pressure volume relationship (EDPVR) and the end-systolic pressure volume relationship (ESPVR) in sham mice and those post angiotensin II treatment. B Likewise, the pressure volume loop recordings in the mice after angiotensin II treatment for 4 weeks showed similar hemodynamic changes compared with the sham mice (n = 10–12 for each group)

Pressure overload induction in both murine models of hypertrophy led to a quantifiable increase in the degree of fibrosis

Using Masson’s trichrome staining, we detected a significant increase in cardiac fibrosis in the mouse hearts post-aortic banding. As expected, the increase in fibrosis diminished after the pressure was relieved by the debanding surgery (Fig. 4A, B). In a similar pattern of onset of fibrosis, mice that underwent Ang II implantation showed a significant increase in myocardial fibrosis compared with baseline (Fig. 4C, D).

A Masson’s trichrome staining showed that increased pericoronary arterial fibrosis improved significantly post debanding. B Quantification of the area of cardiac fibrosis in the three groups (sham, post ascending aortic banding, and debanding). C, D Similarly, infusion of angiotensin II for 4 weeks resulted in a significant increase in fibrosis compared with sham treatment (n = 10–12 for each group)

Angiotensin II treatment but not aortic banding significantly increased the expression of pressure-sensitive proteins accompanied by a decline in CFV

To explore a plausible mechanistic basis for pressure overload induced either by aortic banding or angiotensin II triggering cardiac remodeling in hypertension, we examined the expression of CTGF, HIF-1α, and STAT3 in sham and angiotensin II- or aortic banding-treated left ventricular tissues. In previous studies, CTGF and STAT3 were shown to be upregulated in cardiac hypertrophy in response to pressure overload [20, 21]. In addition, HIF-1α has been observed to mediate the expression of CTGF under stress [22]. Notably, in our study, the above proteins were upregulated in the mouse left ventricle after aortic banding or angiotensin II treatment (Fig. 5A, B).

A In mice after aortic banding for 4 weeks, there were significant changes changes in pressure-sensitive protein expression of connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) compared with sham mice. B Conversely, in mice after angiotensin II treatment for 4 weeks, the expression of the above pressure-sensitive proteins was significantly increased compared with that in sham mice (n = 10–12 for each group)

Reproducibility of CFV measures in human subjects and mice

To determine the reproducibility of coronary flow parameters in humans and mice, echocardiographic images from 20 randomly selected subjects and 10 mice were analyzed by two readers a total of three times each. Each measurement was taken at 10-min intervals. Readers could select the best cardiac cycle and were blinded to previous measurements. The intra- and interobserver reliability showed high correlations in both human subjects (R2 = 0.97 and 0.94, respectively) and mice (R2 = 0.92 and 0.88, respectively) (Supplementary Fig. S4), suggesting a robust measure that was highly reproducible.

Discussion

In this study, we found that (1) changes in CFV in hypertensive patients were specific to antihypertensive regimens (e.g., ARB), rather than reduced systolic blood pressure (e.g., CCB); (2) Despite similar effects of AngII and aortic banding on hemodynamics and cardiac fibrosis, CFV and the expression of pressure-sensitive proteins were primarily affected by angiotensin II-associated cardiac remodeling instead of bare pressure overload. We compared the different impacts of cardiac remodeling after aortic banding and AngII treatment in Table 3 and the Graphic abstract.

While the overriding benefit of antihypertensive agents is thought to be derived from lowering systemic blood pressure, secondary agent-specific effects on microcirculation are likely to play an important contributing role in the process [2, 23]. For instance, ARBs have been found to attenuate left ventricular hypertrophy and preserve diastolic function in diabetic hearts [5, 7]. In addition, ARBs are associated with end-organ protection of the heart, blood vessels and kidneys and in renovascular hypertensive rats [5, 7]. In Hinoi et al. work, ARBs have been further suggested to improve CFV in hypertensive patients in 12 weeks [8]. Likewise, in our study, we found that average CFV in hypertensive patients improved significantly with ARB treatment, in contrast to CCB treatment, which had a minimal effect on coronary parameters, despite a similar blood pressure-lowering effect. Notably, in our murine models, CFV decreased post-angiotensin II infusion, while there were no significant changes in CFV following aortic banding or the subsequent debanding. Our results imply that coronary flow may in part be a direct result of the adverse remodeling process, one that is specifically associated with AngII-induced hypertension and not necessarily by the broadly observed increase in intracardiac pressure that typically accompanies hypertrophy or other cardiac hypertrophic changes.

Under conditions of pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy in hypertrophy, several pressure-sensitive proteins were upregulated. Among them, CTGF, by mediating the ability of transforming growth factor-β, is a key mediator of extracellular matrix production in pathological fibrosis. STAT3, a transcription factor, is important for maintaining metabolic homeostasis and myofilament function [24]. Previous literature showed that STAT3 inhibition in mice protected against AngII-induced hypertrophy, fibrosis, and cardiac functional decline [25]. In addition, HIF-1α, a central transcriptional regulator of the hypoxic response, has been observed to mediate the expression of CTGF under stress [26]. Nevertheless, evidence linking the cardiac expression of these pressure-sensitive proteins and coronary flow alterations is lacking. Our data on the upregulation of angiotensin II-associated proteins, including HIf-1, CTGF, and STAT3, provide insight into a likely mechanism of how small changes in coronary microcirculation lead to larger functional changes over time that reduce blood flow to the myocardium. Notably, previous literature that indicated that HIF-1α does not affect cardiac hypertrophy after aortic banding in mice also echoes our findings that aortic banding and AngII treatment-induced cardiac remodeling might be different [27].

CFR is considered an important physiological parameter in the coronary circulation [28]. However, there is an important drawback in the methodology, as it is commonly measured by intracoronary flow wire, an invasive technique not suitable for repeated measurements. Recently, several reports have shown that epicardial coronary blood flow velocity can be measured by transthoracic Doppler echocardiography, a noninvasive test [19, 29]. Wada and colleagues compared CFRs in three major coronary arteries measured by transthoracic echocardiography with those measured by invasive fractional flow reserve [30]. They suggested that noninvasive CFR measurement could be a reliable method for determining the hemodynamic significance of three major coronary arteries. Calculation of CFR, however, requires induction of hyperemia, typically with an acute vasodilatory agent such as adenosine [23]. Adenosine, however, may induce hypotension and even life-threatening bradycardia [31]. Herein, we estimated the CFR by assessing the CFV, measured in a nonhyperemic state, and found that in both hypertensive humans and mice, it corresponded to changes in hemodynamic pressure as well as cardiac fibrosis.

There are some limitations of this study. First, there was a small number of hypertensive patients enrolled with a follow-up duration of 12 weeks. As previously reported, ARBs were also observed to improve coronary circulation within 12 weeks. Despite the small number, we found a significant change in CFV in patients treated with ARBs. Second, we appreciate that the mouse model of aortic banding may not comprehensively mimic hypertensive patients treated with CCBs. Given that Kim et al. previously published that pressure overload contributes to angiotensin-mediated early remodeling in mouse hearts, we felt that both mouse cohorts, those treated with aortic banding and those treated with an angiotensin II pump, represented a model where there is augmented cardiac fibrosis, but specifically, those treated with angiotensin II showed a significant decline in CFV. The AngII data provide insight into a possible mechanism of CFV modulation that is not entirely due to hemodynamic stress but also involves neurohormonal activation [32]. Third, in this study, there was underrepresentation of females in the clinical cohort, while the mice were all male. Previously, Shukri et al. reported that women had a greater increase in renal plasma flow in response to angiotensin II than men. This finding suggested that women may be more responsive to ARBs than men and implied that aldosterone may contribute to cardiovascular disease differently among sexes [33]. Fourth, in our AAC and AngII models, the follow-up durations were 2 and 4 weeks, respectively, while debanding was performed at 1 week after banding and already showed significant recovery of CFV and regression of cardiac fibrosis. Our data are in line with the 2-week debanding study data by Unno et al., who reported the recovery of LV wall thickness, chamber dimensions and fractional shortening in mice that underwent aortic debanding after 2 weeks. Given that the plasticity of the heart may be reduced during the progression of the disease, an extended length of the initial banding phase facilitates an understanding of the pathological alterations in the myocardium under pressure overload [10]. Nevertheless, the fibrosis at the suture site aggregated rapidly post-aortic banding, while delayed debanding surgery significantly increased postoperative mortality. Finally, according to current studies, ARBs have nearly the same beneficial effects as angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors on cardiac hypertrophy, remodeling, and heart failure [34]. As an alternative approach, ACE inhibitors could also be a choice for preserving coronary flow, but more evidence is required. Our findings also supported the clinical application of CFV as a functional marker for changes in coronary circulation. While it remains to be properly tested in a controlled study, for specific hypertensive patients who are prone to preserve cardiac microcirculation, ARBs could be a superior choice to CCBs.

Collectively, our findings link AngII-induced hemodynamic remodeling and alterations in coronary vasculature, which imply a clinical benefit of ARB treatment in hypertensive patients. Nonetheless, a larger double-blinded controlled study of ARB treatment options for newly diagnosed hypertensive subjects who present with abnormal coronary flow velocity at baseline and discernible improvement after treatment is necessary.

Change history

01 October 2025

The original online version of this article was revised: Figure 5 has been updated.

03 October 2025

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-025-02389-4

References

Chilian WM. Coronary microcirculation in health and disease. Summary of an NHLBI workshop. Circulation. 1997;95:522–8.

Levy BI, Ambrosio G, Pries AR, Struijker-Boudier HA. Microcirculation in hypertension: a new target for treatment? Circulation. 2001;104:735–40.

Camici PG, Olivotto I, Rimoldi OE. The coronary circulation and blood flow in left ventricular hypertrophy. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;52:857–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2011.08.028.

Kawai M, Hongo K, Komukai K, Morimoto S, Nagai M, Seki S, et al. Telmisartan predominantly suppresses cardiac fibrosis, rather than hypertrophy, in renovascular hypertensive rats. Hypertens Res. 2009;32:604–10. https://doi.org/10.1038/hr.2009.61.

Tsutsui H, Matsushima S, Kinugawa S, Ide T, Inoue N, Ohta Y, et al. Angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker attenuates myocardial remodeling and preserves diastolic function in diabetic heart. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:439–49. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.30.439.

Schmermund A, Lerman LO, Ritman EL, Rumberger JA. Cardiac production of angiotensin II and its pharmacologic inhibition: effects on the coronary circulation. Mayo Clin Proc. 1999;74:503–13. https://doi.org/10.4065/74.5.503.

Kamezaki F, Tasaki H, Yamashita K, Shibata K, Hirakawa N, Tsutsui M, et al. Angiotensin receptor blocker improves coronary flow velocity reserve in hypertensive patients: comparison with calcium channel blocker. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:699–706. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.30.699.

Hinoi T, Tomohiro Y, Kajiwara S, Matsuo S, Fujimoto Y, Yamamoto S, et al. Telmisartan, an angiotensin II type 1 receptor blocker, improves coronary microcirculation and insulin resistance among essential hypertensive patients without left ventricular hypertrophy. Hypertens Res. 2008;31:615–22. https://doi.org/10.1291/hypres.31.615.

Packer M. Pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the adverse effects of calcium channel-blocking drugs in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1989;80:IV59–67.

Unno K, Oikonomopoulos A, Fujikawa Y, Okuno Y, Narita S, Kato T, et al. Alteration in ventricular pressure stimulates cardiac repair and remodeling. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2019;133:174–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yjmcc.2019.06.006.

Goyal J, Khan ZY, Upadhyaya P, Goyal B, Jain S. Comparative study of high dose mono-therapy of amlodipine or telmisartan, and their low dose combination in mild to moderate hypertension. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:HC08–11. https://doi.org/10.7860/JCDR/2014/9352.4500.

Shimizu Y, Yamasaki F, Furuno T, Kubo T, Sato T, Doi Y, et al. Metabolic effect of combined telmisartan and nifedipine CR therapy in patients with essential hypertension. Int J Gen Med. 2012;5:753–8. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJGM.S28890.

Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor-Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A, Ernande L, et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2015;28:1–39 e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.003.

Wada T, Hirata K, Shiono Y, Orii M, Shimamura K, Ishibashi K, et al. Coronary flow velocity reserve in three major coronary arteries by transthoracic echocardiography for the functional assessment of coronary artery disease: a comparison with fractional flow reserve. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;15:399–408. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jet168.

deAlmeida AC, van Oort RJ, Wehrens XH. Transverse aortic constriction in mice. Journal of visualized experiments: JoVE. 2010;. https://doi.org/10.3791/1729.

Lu H, Howatt DA, Balakrishnan A, Moorleghen JJ, Rateri DL, Cassis LA, et al. Subcutaneous angiotensin II infusion using osmotic pumps induces aortic aneurysms in mice. J Visual Exp. 2015;. https://doi.org/10.3791/53191.

Krege JH, Hodgin JB, Hagaman JR, Smithies O. A noninvasive computerized tail-cuff system for measuring blood pressure in mice. Hypertension 1995;25:1111–5. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.hyp.25.5.1111.

Townsend D. Measuring pressure volume loops in the mouse. J Visual Exp. 2016. https://doi.org/10.3791/53810.

Chang WT, Fisch S, Chen M, Qiu Y, Cheng S, Liao R. Ultrasound based assessment of coronary artery flow and coronary flow reserve using the pressure overload model in mice. J Visual Exp. 2015:e52598. https://doi.org/10.3791/52598.

Haghikia A, Stapel B, Hoch M, Hilfiker-Kleiner D. STAT3 and cardiac remodeling. Heart Fail Rev. 2011;16:35–47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-010-9170-x.

Szabo Z, Magga J, Alakoski T, Ulvila J, Piuhola J, Vainio L, et al. Connective tissue growth factor inhibition attenuates left ventricular remodeling and dysfunction in pressure overload-induced heart failure. Hypertension 2014;63:1235–40. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03279.

Higgins DF, Biju MP, Akai Y, Wutz A, Johnson RS, Haase VH. Hypoxic induction of Ctgf is directly mediated by Hif-1. Am J Physiol Ren Physiol. 2004;287:F1223–32. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajprenal.00245.2004.

Ikonomidis I, Tzortzis S, Paraskevaidis I, Triantafyllidi H, Papadopoulos C, Papadakis I, et al. Association of abnormal coronary microcirculatory function with impaired response of longitudinal left ventricular function during adenosine stress echocardiography in untreated hypertensive patients. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;13:1030–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehjci/jes071.

Daniels JT, Schultz GS, Blalock TD, Garrett Q, Grotendorst GR, Dean NM, et al. Mediation of transforming growth factor-beta(1)-stimulated matrix contraction by fibroblasts: a role for connective tissue growth factor in contractile scarring. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2043–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0002-9440(10)63562-6.

Han J, Ye S, Zou C, Chen T, Wang J, Li J, et al. Angiotensin II causes biphasic STAT3 activation through TLR4 to initiate cardiac remodeling. Hypertension. 2018;72:1301–11. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11860.

Xiong A, Liu Y. Targeting hypoxia inducible factors-1alpha as a novel therapy in fibrosis. Front Pharm. 2017;8:326 https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2017.00326.

Silter M, Kogler H, Zieseniss A, Wilting J, Schafer K, Toischer K, et al. Impaired Ca(2+)-handling in HIF-1alpha(+/-) mice as a consequence of pressure overload. Pflug Arch. 2010;459:569–77. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00424-009-0748-x.

Hartley CJ, Reddy AK, Michael LH, Entman ML, Taffet GE. Coronary flow reserve as an index of cardiac function in mice with cardiovascular abnormalities. In: Proceedings of the Annual International Conference on IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society 2009; 2009:1094–7. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5332488.

Taqueti VR, Hachamovitch R, Murthy VL, Naya M, Foster CR, Hainer J, et al. Global coronary flow reserve is associated with adverse cardiovascular events independently of luminal angiographic severity and modifies the effect of early revascularization. Circulation. 2015;131:19–27. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.011939.

Wang X, Wu J, Zhu D, You J, Zou Y, Qian J, et al. Characterization of coronary flow reserve and left ventricular remodeling in a mouse model of chronic aortic regurgitation with carvedilol intervention. J Ultrasound Med. 2015;34:483–93. https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.34.3.483.

Layland J, Carrick D, Lee M, Oldroyd K, Berry C. Adenosine: physiology, pharmacology, and clinical applications. JACC Cardiovasc Intervent. 2014;7:581–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcin.2014.02.009.

Kim JH, Jiang YP, Cohen IS, Lin RZ, Mathias RT. Pressure-overload-induced angiotensin-mediated early remodeling in mouse heart. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0176713 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0176713.

Shukri MZ, Tan JW, Manosroi W, Pojoga LH, Rivera A, Williams JS, et al. Biological sex modulates the adrenal and blood pressure responses to angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2018;71:1083–90. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.117.11087.

Yoshiyama M, Nakamura Y, Omura T, Izumi Y, Matsumoto R, Oda S, et al. Angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor prevents left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction in angiotensin II type 1 receptor knockout mice. Heart. 2005;91:1080–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2004.035618.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Chi-Mei Medical Center, Scientist Developed Grant of National Health Research Institute, Taiwan (NHRI-EX106- 10618SC), Ministry of Science and Technology (MOST 109-2326-B-384 -001 -MY3) (W-T Chang), and National Institute of Health grants R01HL131532 (SC), R01HL134168 (SC), HL093148 (RL), HL128135 (RL) and HL099073 (RL).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

The original online version of this article was revised: Figure 5 has been updated.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, WT., Fisch, S., Dangwal, S. et al. Angiotensin II blockers improve cardiac coronary flow under hemodynamic pressure overload. Hypertens Res 44, 803–812 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00617-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00617-1