Abstract

Increased visit-to-visit variability (VVV) of blood pressure, which is calculated based on several readings, has been suggested to be a significant predictor of cardiovascular events and mortality, independent of mean blood pressure. This study examined associations between the VVV of systolic blood pressure (SBP) measured annually and cardiovascular disease (CVD) events among 72,617 Japanese subjects. Data were obtained from the Japan Epidemiology Collaboration on Occupational Health Study, which is an ongoing epidemiological survey of workers in Japan. VVV was calculated as the coefficient of variation of SBP readings from 2008 to 2011; information on fatal and nonfatal CVD events was collected from registries of specific outcomes between April 2012 and March 2019. A Cox proportional hazards model was applied to investigate associations after adjusting for mean SBP between 2008 and 2011 and covariates. During the 7-year follow-up period, there were 63 CVD fatalities and 314 CVD events (combining fatal and nonfatal events). The results showed that a one-standard deviation increase in VVV was associated with a significant increase in the risk of CVD mortality (hazard ratio [HR] = 1.42; 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.32–1.54); those in the highest tertile had a 3.20 times (95% CI = 1.26–8.17) higher risk of CVD mortality than those in the lowest tertile. We found less pronounced associations regarding CVD events (HR = 1.08, 95% CI = 1.02–1.15). In conclusion, VVV was significantly associated with CVD mortality in our Japanese working population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Although high blood pressure has long been recognized as a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and mortality [1, 2], a growing body of literature suggests that increased visit-to-visit variability (VVV) of blood pressure, which is calculated based on several readings measured at daily, monthly, or annual intervals [3, 4], is also a significant predictor of CVDs and mortality, independent of mean blood pressure [5,6,7,8]. A meta-analysis by Diaz et al. [5] showed that a 5 mmHg increase in VVV (expressed as the standard deviation [SD] of systolic blood pressure [SBP]) was associated with a 17% higher risk of stroke, 27% higher risk of coronary heart disease (CHD), 12% higher risk of CVD, 22% higher risk of CVD mortality, and 20% higher risk of all-cause mortality. Moreover, several studies have suggested that greater blood pressure variability may reflect an inability to maintain homeostasis, with damage to vascular tissues and end organs [9, 10].

Our study builds on this previous work in the following manner. First, we investigated VVV in working-age participants. Given that most previous studies on this topic have focused on the VVV in clinical settings [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21] or in older populations [15, 22,23,24], examining VVV in a working-age population may help to determine whether it can be used to identify those at risk of CVD events at an earlier stage of life. Second, we examined the association between VVV and CVD subtypes (i.e., stroke and CHD). Third, few attempts have been made to compare results among different VVV indices (i.e., SD, coefficient of variation [CV], variability independent of the mean [VIM] and average absolute difference between successive values [ASV]), even though the use of these indices has been recommended to allow for comparison among studies [25].

Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine the association between VVVs of SBP and CVD mortality and events, with particular attention to the effects of different VVV indicators on the outcomes.

Methods

Study cohort

We used information collected in the Japan Epidemiology Collaboration on Occupational Health (J-ECOH) Study, which is an ongoing epidemiological survey investigating health determinants in workers in Japan across various industrial sectors [26,27,28]. In Japan, employers must organize general health check-ups for their employees at least once per year under the Industrial Safety and Health Act. We obtained anthropometric and biochemical data collected during check-ups since 2008. Questionnaire data (medical history and lifestyle parameters) were also collected.

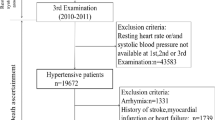

We included subjects who provided information on blood pressure at least three times out of four collection waves (2008–2011) before the launch of the study registries on specific outcomes in April 2012 (described below) and calculated the VVV of blood pressure. Of the 110,149 workers at the 11 worksites who participated in the J-ECOH study since 2008 or 2009, we excluded those for whom blood pressure was obtained fewer than three times (n = 26,751), those with missing information on covariates at baseline (2011, or 2010 if information was unavailable in 2011, n = 2211) and those who were previously diagnosed with CVD (n = 1246) or cancer at baseline (n = 857). We also excluded subjects without follow-up data (n = 6467). Ultimately, our final sample included 72,617 subjects (62,855 men and 9762 women).

The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (Tokyo, Japan; approval number: NCGM-G-001140). We enrolled participants who did not opt out via the internal bulletin boards of individual companies. We did not obtain informed consent from each participant but did inform workers of the purposes and procedures of the study, and they were able to withdraw their participation at any time during the study. This procedure conformed to the Japanese Ethical Guidelines for Epidemiological Research for observational studies using preexisting data.

Follow-up

Registries on specific outcomes were launched in April 2012 to obtain data on CVD events (myocardial infarction [MI] and stroke), long-term sickness absence (LTSA; i.e., sickness absence lasting for 30 consecutive days or longer) and mortality. This information was reported to the J-ECOH study group by occupational physicians at each worksite. Cause of LTSA was determined based on certificates issued by the attending doctors. On the other hand, cause of death was confirmed based on death certificates, sickness absence documents, confirmation by the family, and other sources; the first two sources accounted for ~80% of all confirmations [29]. The reported causes were later coded by the J-ECOH study group using the International Classification of Disease 10th edition (ICD-10).

Outcomes

Outcomes were (1) CVD mortality and (2) CVD events reported via the registries for specific outcomes (i.e., CVD, LTSA, and mortality registries) between April 1, 2012, and March 31, 2019. In this study, CVD was defined as (1) ischemic heart diseases except angina pectoris (ICD-10: I21–I25); (2) cardiac arrest (I46); (3) atrial fibrillation and heart failure (I48–I50); (4) cerebrovascular diseases (I60–69); and (5) aortic aneurysm and dissection and other aneurysms (I71–72). We also examined associations with secondary outcomes, i.e., fatal stroke (I60–69) and fatal CHD (I21–25, I46, I48–50, I71–72).

In the analysis of CVD mortality, person-time was calculated from March 31, 2012 (i.e., 1 day before the beginning of the follow-up period) to the date of death for those who died following a CVD event during the study period. Those who survived a CVD event were censored on one of the following dates (if any): (1) the date of death due to causes other than CVD, (2) the date of return-to-work after long-term sick leave, or (3) the first day of long-term sick leave, whichever occurred last. Similarly, in the analysis of CVD events, person-time was calculated from March 31, 2012, to the date of the CVD event (fatal or nonfatal) for those who experienced a CVD event during the study period. Those who took long-term sick leave due to CVD, without any prior report of CVD in the study registries, were followed-up from March 31, 2012, to the first date of long-term sick leave. In both analyses, if participants did not experience any of the abovementioned events, they were considered to be under observation until the last day of the fiscal year (i.e., March 31), in which the last health check-up was performed.

Explanatory variables

Blood pressure was measured in a sitting position by trained nurses as a part of the mandatory health check-up [30]. Other measurement conditions at each worksite are described in Supplementary Table 1. Four worksites, which provided information for more than 80% of the study participants, required their employees rest for a certain amount of time prior to the first measurement (e.g., 1–5 min); no information was available for the other worksites. Of the 11 worksites involved in this study, only two measured blood pressure twice; the other worksites measured blood pressure twice only when high blood pressure was noted at the first measurement (SBP/diastolic blood pressure [DBP] > 150/>90 mmHg; >140/>90 mmHg; or >130 mmHg/>85 mmHg). In this study, we analyzed the first SBP measurement, except for the employees of one company, which provided the lower of the two measurements. The first blood pressure measurement was obtained using an automated sphygmomanometer (nine sites) or a mercury sphygmomanometer (two sites).

The VVV of SBP was calculated using SBP data for 2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011. We used the CV as the primary exposure variable, as it was the most commonly used variable in previous studies, but we also calculated the SD, VIM, and ASV, per a previous study [25]. VIM was calculated by dividing the SD by the mean to the power at which the correlation between the mean BP and SD was removed. ASV was calculated as the sum of the absolute difference between successive blood pressure readings divided by the number of readings. To ensure comparability among the indices of VVV, we standardized them according to a mean of 0 and an SD of 1.

Covariates

Demographic and anthropometric information collected during the study included age group (<30, 30–39, 40–49, 50–59, or ≥60 years old as of 2011), sex, mean SBP over the period 2008–2011, and body mass index (<18.5, 18.5–24.9, 25.0–29.9, or ≥30 kg/m2). Body height and weight were measured using standardized equipment; height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm, and weight was measured in light clothes, without shoes, to the nearest 0.1 kg. BMI was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height squared (m2). Smoking status was determined using a self-administered questionnaire (currently smoking or not currently smoking).

An individual was considered to use antihypertensive medication when they self-reported the use of such medication at least once during the period 2008–2011. We also determined diabetes and dyslipidemia status at baseline. Diabetes was defined as the presence of any of the following: fasting plasma glucose level ≥126 mg/dL, HbA1c concentration ≥6.5%, random plasma glucose level ≥200 mg/dL, or current use of antidiabetic medication [31]. Dyslipidemia was defined as the presence of any of the following: triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥140 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol <40 (males) or <50 mg/dL (females), or taking antidyslipidemia medication [32].

Statistical analysis

The basic characteristics of the study subjects were analyzed by tertiles of VVV, as defined by the CV of SBP readings obtained between 2008 and 2011. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was used to investigate associations of the VVV of SBP with CVD mortality and CVD events (fatal and nonfatal events) between April 2012 and March 2019. VVV was analyzed as a continuous variable or according to tertile. We adjusted for covariates, including mean SBP and antihypertensive medication use during the period 2008–2011 as well as age, sex, BMI, smoking status, diabetes, and dyslipidemia at baseline (2011). The proportional hazard assumption was assessed using Schoenfeld’s test. When the proportional hazard assumption for covariates was violated, we modeled them as time-varying covariates. We also accounted for clustering by study site.

Furthermore, we conducted the same analyses separately for fatal stroke and fatal CHD as outcomes. Individuals who experienced a CVD event other than the outcome of interest during the follow-up period were censored on the date of the event. In addition, we performed an analysis examining associations using VVV of diastolic blood pressure as the exposure.

To test the robustness of the study findings, we conducted the following two sets of sensitivity analyses. First, we confined the study participants to those not taking antihypertensive medication during the period 2008–2011 (n = 65,062). Second, given that blood pressure is influenced by seasonal changes in outdoor temperature [8, 33], we conducted the same set of analysis while excluding participants with inconsistent timing of blood pressure measurement among study visits (n = 49,101). More specifically, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 1, we used information on the month and day of each measurement and created an indicator of the inconsistency in timing within a year of study visits (i.e., the total number of days between the visits, which was divided by the number of study visit pairs) and excluded those in the highest tertile.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata software (ver. 16.0; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). The results are shown as hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

The basic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age [SD] was 43.2 [10.7] years, with the oldest age observed in the highest VVV tertile. More than 85% of the participants were male. More than one-third of the participants smoked (34.5%). Participants with diabetes and dyslipidemia comprised 6.6% and 41.6% of the cohort, respectively, with the prevalence of both diseases being greatest in the highest VVV tertile.

Sixty-three CVD mortality cases and 314 CVD events (fatal and nonfatal events combined) were encountered during the 7-year follow-up (411,631 person-years for CVD mortality; 411,014 person-years for CVD events). The incidence rate of CVD mortality per 10,000 person-years was 1.53 (95% CI: 1.20–1.96), and that for CVD events was 7.64 (95% CI: 6.84–8.53).

As shown in Table 2, a Cox hazards regression model revealed that a 1-SD increase in VVV, as defined by the CV, was associated with a significantly increased risk of CVD mortality (HR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.32–1.54). The corresponding HRs for the analysis using other definitions to calculate VVV ranged from 1.31 to 1.43 and were all significant. When the VVV tertile was used as the exposure variable, those in the highest tertile were at a higher risk of CVD mortality, with HRs ranging from 2.43 to 3.53. The HRs related to CVD events were generally smaller than those related to CVD mortality (e.g., 1.06–1.08 for the continuous VVV indicators), regardless of the definition used to calculate VVV.

VVV was associated with a higher risk of the secondary outcomes of fatal stroke and fatal CHD, though some associations did not reach significance (Table 3). Participants in the highest tertile, as defined by the CV, had a 2.87 (95% CI = 1.00–8.21) and 3.54 (95% CI = 1.22–10.25) times higher risk of stroke mortality and CHD mortality, respectively. Analyses using the other definitions of VVV yielded similar findings, except for that of the association between VVV defined by ASV and stroke mortality.

We also observed similar results when we used information on diastolic blood pressure to compute VVV indicators (Supplementary Table 2). Specifically, VVV of DBP was significantly associated with CVD mortality (e.g., VVV defined by CV: HR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.09–1.53), but the associations for CVD events were smaller in magnitude (e.g., VVV defined by CV: HR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.04–1.17). Moreover, we did not observe substantial changes in the results when we confined the analysis to participants not taking antihypertensive medication during the period 2008–2011 (Supplementary Table 3) or when we excluded participants with inconsistent timing of blood pressure measurement among study visits (Supplementary Table 4).

Discussion

This study showed that among the Japanese working population, increased VVV of SBP measured annually was associated with a significantly higher risk for CVD mortality while we did not find strong evidence with regard to CVD events. Analyses comparing CVD subtype (i.e., stroke and CHD) data did not reveal a difference, as fatal stroke and fatal CHD events showed significant associations. The results did not differ markedly according to the VVV indices used.

The positive association between VVV and CVD mortality observed in our study agrees with the findings of previous meta-analyses [5,6,7,8]. For example, Diaz et al. [5] reported an HR increase of 1.22 per 5 mmHg of VVV (defined based on the SD) for CVD mortality. Among the general population, the association between VVV and CVD mortality has not been well studied compared to that between VVV and all-cause mortality [34,35,36]. One example is Choi et al. [37], who investigated the association in the general Korean population (mean age, 49.9–53.8 years, n = 51,811) over a 4-year period, finding no evidence of a significant association (HR = 1.32, 95% CI = 0.89–1.94), which may have been partially due to the small number of events. Our study adds to the literature by showing a significant association between VVV and fatal CVD events in a working population.

However, the less pronounced relationship between VVV and CVD events vs. CVD mortality observed in our study was not in line with previous reports. For example, the abovementioned meta-analysis by Diaz et al. [5] reported similar HRs for CVD mortality (HR = 1.22), CVD events (a composite outcome comprised of fatal and nonfatal events; HR = 1.12) and CHD (HR = 1.27), suggesting an increased risk of nonfatal CVD events among those with a larger VVV. In addition, Choi et al. [37] reported VVV (defined as an SD of SBP of >10 mmHg) to be associated with a higher risk of nonfatal MI or stroke (HR = 1.45) in the general Korean population. We could not confirm whether our less-pronounced association was a chance finding or reflected the true nature of the relationship in this particular study population (e.g., due to their relatively young ages). It should be noted that some studies on associations of other independent variables with CVD events have suggested that the underlying mechanisms of fatal and nonfatal outcomes may differ [38, 39].

Although previous studies differed in terms of the time interval between visits (ranging from 2 days to 4 years), the association between VVV and cardiovascular events persisted, even when only those that used relatively long intervals between measurements, as in our study (i.e., ≥1 year), were considered: increased VVV was associated with a higher risk of heart disease [22, 40, 41], stroke [42] and CVD mortality [43]. Nevertheless, there were some inconsistencies; for example, Suchy-Dicey et al. [22] reported a significant association of VVV with MI but not with stroke. In addition, our study did not find any evidence for an association between VVV and CVD events, as stated above. Overall, VVV of SBP measured annually is a potentially important predictor of CVD events, yet more research is needed to determine whether this association is present in other populations.

Our results did not differ according to the definition of VVV used. The results obtained using the VIM-based definition of VVV were conservative, as they were calculated by dividing the SD by the mean (i.e., CV) and considering the correlation between the mean BP and SD. However, using CV or VIM as an index of VVV while simultaneously adjusting for the mean SBP, as in our regression model, may have led to overadjustment. Future studies should follow the recommendation of Dolan et al. [25] that four indices of VVV be used, per this study, to allow for meaningful comparisons among studies.

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, information on blood pressure was collected as part of annual health checkups conducted at each participating company, and there was no uniform protocol across the companies. Systematic errors can arise due to different types of sphygmomanometers utilized or the difference in resting time before measurement among the study companies. In addition, we did not have information regarding when blood pressure was measured or the outdoor temperature on the day when it was measured. Second, we did not assess some of the variables that may have explained the association between VVV and mortality, e.g., adherence to antihypertensive medication. Nonetheless, Supplementary Table 1 shows that the results did not change substantially when we confined our analysis to participants who did not take antihypertensive medications. Third, our study participants may not have been fully representative of the Japanese working-age population, as they were all drawn from relatively large companies and were predominantly male.

In conclusion, in this analysis of a cohort of 72,617 Japanese workers drawn from the J-ECOH study, the VVV of SBP measured annually was associated with an increased risk of fatal CVD events, but we found no strong evidence of an association with CVD events.

References

Lackland DT, Weber MA. Global burden of cardiovascular disease and stroke: hypertension at the core. Can J Cardiol. 2015;31:569–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2015.01.009

Forouzanfar MH, Liu P, Roth GA, Ng M, Biryukov S, Marczak L, et al. Global burden of hypertension and systolic blood pressure of at least 110 to 115 mm Hg, 1990–2015. JAMA. 2017;317:165–82. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.19043

Hussein WF, Chang TI. Visit-to-visit variability of systolic blood pressure and cardiovascular disease. Curr Hypertens Rep. 2015;17:14 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-014-0527-8

Dolan E, O’Brien E. Is it daily, monthly, or yearly blood pressure variability that enhances cardiovascular risk? Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17:93 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11886-015-0649-x

Diaz KM, Tanner RM, Falzon L, Levitan EB, Reynolds KS, Daichi MP. Visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure and cardiovascular disease and all-cause mortality. Hypertension. 2014;64:965–82. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.03903

Wang J, Shi X, Ma C, Zheng H, Xiao J, Bian H, et al. Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability is a risk factor for all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertension. 2017;35:10–17. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000001159

Tai C, Sun Y, Dai N, Xu D, Chen W, Wang J, et al. Prognostic significance of visit-to-visit systolic blood pressure variability: a meta-analysis of 77,299 patients. J Clin Hypertension. 2015;17:107–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12484

Parati G, Ochoa JE, Lombardi C, Bilo G. Assessment and management of blood-pressure variability. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10:143–55. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrcardio.2013.1

Laurent S, Boutouyrie P. Visit-to-visit blood pressure variability: added ‘VALUE’ as a risk marker in low- and high-risk patients. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2252–4. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehy011

Mancia G, Parati G. The role of blood pressure variability in end-organ damage. J Hypertension. 2003;21:S17.

Di Iorio B, Pota A, Sirico ML, Torraca S, Di Micco L, Rubino R, et al. Blood pressure variability and outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transpl. 2012;27:4404–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfs328

Hsieh Y-T, Tu S-T, Cho T-J, Chang S-J, Chen J-F, Hsieh M-C. Visit-to-visit variability in blood pressure strongly predicts all-cause mortality in patients with type 2 diabetes: a 5·5-year prospective analysis. Eur J Clin Investig. 2012;42:245–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2362.2011.02574.x

Mallamaci F, Minutolo R, Leonardis D, D’Arrigo G, Tripepi G, Rapisarda F, et al. Long-term visit-to-visit office blood pressure variability increases the risk of adverse cardiovascular outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2013;84:381–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/ki.2013.132

McMullan CJ, Bakris GL, Phillips RA, Forman JP. Association of BP variability with mortality among African Americans with CKD. CJASN. 2013;8:731–8. https://doi.org/10.2215/CJN.10131012

Kostis JB, Sedjro JE, Cabrera J, Cosgrove NM, Pantazopoulos JS, Kostis WJ, et al. VisiT-to-visit Blood Pressure Variability and Cardiovascular Death in the Systolic Hypertension in the Elderly Program. J Clin Hypertension. 2014;16:34–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12230

Lau K-K, Wong Y-K, Teo K-C, Chang RSK, Chan K-H, Hon SFK, et al. Long-term prognostic implications of visit-to-visit blood pressure variability in patients with ischemic stroke. Am J Hypertens. 2014;27:1486–94. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpu070

Gondo K, Miura S, Suematsu Y, Shiga Y, Kuwano T, Sugihara M, et al. Association between visit-to-visit variability in blood pressure and cardiovascular events in hypertensive patients after successful percutaneous coronary intervention. J Clin Med Res. 2015;7:545–50–550. https://doi.org/10.14740/jocmr.v7i7.2173

Chang TI, Tabada GH, Yang J, Tan TC, Go AS. Visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure and death, end-stage renal disease, and cardiovascular events in patients with chronic kidney disease. J Hypertension. 2016;34:244–52. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000779

Men X, Sun W, Fan F, Min Z, Huang X, Wang Y, et al. China stroke primary prevention trial: visit‐to‐visit systolic blood pressure variability is an independent predictor of primary stroke in hypertensive patients. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e004350. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.004350

Wightman SS, Sainsbury CAR, Jones GC. Visit-to-visit HbA1c variability and systolic blood pressure (SBP) variability are significantly and additively associated with mortality in individuals with type 1 diabetes: an observational study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:1014–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/dom.13193

Seo SM, Chung W-B, Choi IJ, Koh Y-S, Ihm S-H, Kim P-J, et al. Visit-to-visit variability of systolic blood pressure predicts all-cause mortality in patients received percutaneous coronary intervention with drug-eluting stents. Heart Vessels. 2018;33:489–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00380-017-1085-1

Suchy-Dicey AM, Wallace ER, Elkind MS, Aguilar M, Gottesman RF, Rice K, et al. Blood pressure variability and the risk of all-cause mortality, incident myocardial infarction, and incident stroke in the cardiovascular health study. Am J Hypertens. 2013;26:1210–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpt092

Muntner P, Whittle J, Lynch AI, Colantonio LD, Simpson LM, Einhorn PT, et al. Visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure and coronary heart disease, stroke, heart failure, and mortality: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:329 https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-2803

Gosmanova EO, Mikkelsen MK, Molnar MZ, Lu JL, Yessayan LT, Kalantar-Zadeh K, et al. Association of systolic blood pressure variability with mortality, coronary heart disease, stroke, and renal disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;68:1375–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.06.054

Dolan Eamon O’BrienEoin. Blood pressure variability. Hypertension. 2010;56:179–81. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.154708

Hu H, Nakagawa T, Honda T, Yamamoto S, Nanri A, Konishi M, et al., Metabolic Syndrome Over 4 Years Before the Onset of Cardiovascular Disease—Nested Case-Control Study—. Circ J. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-17-0513

Endo M, Inoue Y, Kuwahara K, Nishiura C, Hori A, Ogasawara T, et al. and Medically Certified Long-Term Sickness Absence Among Japanese Employees. Obesity. 2020;28:437–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22703

Hori A, Inoue Y, Kuwahara K, Kunugita N, Akter S, Nishiura C, et al. Smoking and long-term sick leave in a Japanese working population: Findings of the Japan Epidemiology Collaboration on Occupational Health Study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23:135-42. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntz204.

Akter S, Nakagawa T, Honda T, Yamamoto S, Kuwahara K, Okazaki H, et al. Smoking, Smoking Cessation, and Risk of Mortality in a Japanese Working Population—Japan Epidemiology Collaboration on Occupational Health Study—. Circulation J. 2018;82:3005–12. https://doi.org/10.1253/circj.CJ-18-0404

Hu H, Hori A, Nishiura C, Sasaki N, Okazaki H, Nakagawa T, et al. HbA1c, Blood Pressure, and Lipid Control in People with Diabetes: Japan Epidemiology Collaboration on Occupational Health Study. PLOS ONE. 2016;11:e0159071 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0159071

Diagnosis | ADA. https://www.diabetes.org/a1c/diagnosis. Accessed 13 June 2020

Teramoto T, Sasaki J, Ishibashi S, Birou S, Daida H, Dohi S, et al. Japan Atherosclerosis Society. Executive summary of the Japan Atherosclerosis Society (JAS) guidelines for the diagnosis and prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases in Japan -2012 version. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2013;20:517–23. https://doi.org/10.5551/jat.15792

Parati G, Torlasco C, Pengo M, Bilo G, Ochoa JE. Blood pressure variability: its relevance for cardiovascular homeostasis and cardiovascular diseases. Hypertension Res. 2020;43:609–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-020-0421-5

Dai L, Song L, Li X, Yang Y, Zheng X, Wu Y, et al. Association of visit-to-visit blood pressure variability with the risk of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in general population. J Clin Hypertension. 2018;20:280–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13192

Pannier B, Thomas F, Hanon O, Czernichow S, Lemogne C, Simon T, et al. Individual 6-year systolic blood pressure change and impact on cardiovascular mortality in a French general population. J Hum Hypertens. 2016;30:18–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/jhh.2015.44

Muntner Paul, Shimbo Daichi, Tonelli Marcello, Reynolds Kristi, Arnett DonnaK, Oparil Suzanne. The relationship between visit-to-visit variability in systolic blood pressure and all-cause mortality in the general population. Hypertension. 2011;57:160–6. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.110.162255

Choi S, Shin J, Choi SY, Sung KC, Ihm SH, Kim K, et al. Impact of Visit-to-visit Variability in Systolic Blood Pressure on Cardiovascular Outcomes in Korean national health insurance service—national sample cohort. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30:577–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajh/hpw157

Logue J, Murray HM, Welsh P, Shepherd J, Packard C, Macfarlane P, et al. Obesity is associated with fatal coronary heart disease independently of traditional risk factors and deprivation. Heart. 2011;97:564–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2010.211201

Sattar N, Murray HM, Welsh P, Blauw GJ, Buckley BM, Cobbe S, et al. Group for the PS of P in the E at R (PROSPER) S. Are Markers of Inflammation More Strongly Associated with Risk for Fatal Than for Nonfatal Vascular Events? PLOS Med. 2009;6:e1000099 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000099

Grove JS, Reed DM, Yano K, Hwang L-J. Variability in Systolic Blood Pressure—A Risk Factor for Coronary Heart Disease? Am J Epidemiol. 1997;145:771–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009169

Brickman AM, Reitz C, Luchsinger JA, Manly JJ, Schupf N, Muraskin J, et al. Long-term blood pressure fluctuation and cerebrovascular disease in an elderly cohort. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:564–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneurol.2010.70

Shimbo D, Newman JD, Aragaki AK, LaMonte MJ, Bavry AA, Allison M, et al. Association between Annual Visit-to-Visit Blood Pressure Variability and Stroke in Postmenopausal Women: Data from the Women’s Health Initiative. Hypertension. 2012;60:625–30. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.193094

Yinon L, Chen Y, Parvez F, Bangalore S, Islam T, Ahmed A, et al. A prospective study of variability in systolic blood pressure and mortality in a rural Bangladeshi population cohort. Preventive Med. 2013;57:807–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.09.006

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Toshiteru Okubo (Chairperson of Industrial Health Foundation, Director of Radiation Effects Research Foundation) for scientific advice on the conduct of the J-ECOH Study and Nobumi Katayama, Rika Osawa, Mika Shichishima, Haruka Miyake (National Center for Global Health and Medicine) for administrative support.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the Industrial Health Foundation (140202-01, 150903-01, 170301-01), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS KAKENHI JP16H05251) and the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (28-Shi-1206).

The J-ECOH study group

Seitaro Dohi5, Hiroko Okazaki5, Isamu Kabe14, Tohru Nakagawa3, Shuichiro Yamamoto3, Toru Honda3, Toshiaki Miyamoto6, Takeshi Kochi4, Masafumi Eguchi4, Taiki Shirasaka4, Isagi Mizuta10, Makoto Yamamoto10, Naoko Sasaki8, Takayuki Ogasawara8, Makiko Shimizu7, Naoki Gonmori7, Akihiko Uehara9, Kayo Kitahara15, Toshitaka Yokoya15, Ai Hori12, Chihiro Nishiura16, Teppei Imai17, Akiko Nishihara18, Kenji Fukasawa19, Kenya Yamamoto20, Reiko Kuroda20, Noritada Kato21, Masatoshi Kawashima22, Kentaro Tomita11, Chihiro Kinugawa23, Takafumi Totsuzaki24, Masashi Masuda25, Nobuaki Sakamoto26, Yohei Ohsaki26, Aki Tomizawa26, Satsue Nagahama27, Mayumi Ohtsu28, Motoki Endo29, Hiroshi Nakashima30, Masauyki Tatemichi31, Kota Fukai31, Megumi Kawashima32, Naoki Kunugita33, Tomofumi Sone34, Toshiteru Ohkubo35, Tetsuya Mizoue31, Yosuke Inoue1, Takako Miki1, Ami Fukunaga1, Shohei Yamamoto1, Maki Konishi1, Nobumi Katayama1, Rika Osawa1, Keisuke Kuwahara1,2

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Members of the J-ECOH study group are listed below Funding.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Inoue, Y., Kuwahara, K., Hu, H. et al. Visit-to-visit variability of blood pressure and cardiovascular events among the working-age population in Japan: findings from the Japan Epidemiology Collaboration on Occupational Health Study. Hypertens Res 44, 1017–1025 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00654-w

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00654-w

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

Association between occupational stress responses and cardiovascular disease incidence in middle-aged Japanese: findings from the Aichi workers’ cohort study

International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health (2026)

-

Physiological measures variability and risks of heart disease and stroke: evidence from three cohort studies

BMC Medicine (2024)

-

Blood pressure classification using the Japanese Society of Hypertension Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension and cardiovascular events among young to middle-aged working adults

Hypertension Research (2024)

-

The association between living alone and depressive symptoms and the role of pet ownership among Japanese workers

BMC Public Health (2023)

-

The relationship between day-to-day variability in home blood pressure measurement and multiple organ function

Hypertension Research (2022)