Abstract

Xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR), a rate-limiting and catalyzing enzyme of uric acid formation in purine metabolism, is involved in reactive oxygen species generation. Plasma XOR activity has been shown to be a novel metabolic biomarker related to obesity, liver dysfunction, hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia, and insulin resistance. However, the association between plasma XOR activity and hypertension has not been fully elucidated. We investigated the association of hypertension with plasma XOR activity in 271 nondiabetic subjects (male/female: 119/152) who had not taken any medications in the Tanno–Sobetsu Study, a population-based cohort. Males had higher plasma XOR activity than females. Plasma XOR activity was positively correlated with mean arterial pressure (r = 0.128, P = 0.036). When the subjects were divided by the presence and absence of hypertension into an HT group (male/female: 34/40) and a non-HT group (male/female: 85/112), plasma XOR activity in the HT group was significantly higher than that in the non-HT group (median: 39 vs. 28 pmol/h/mL, P = 0.028). There was no significant difference in uric acid levels between the two groups. Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that plasma XOR activity (odds ratio: 1.091 [95% confidence interval: 1.023–1.177] per 10 pmol/h/mL, P = 0.007) was an independent determinant of the risk for hypertension after adjustment for age, sex, current smoking and alcohol consumption, estimated glomerular filtration rate, brain natriuretic peptide, and insulin resistance index. The interaction of sex with plasma XOR activity was not significant for the risk of hypertension. In conclusion, plasma XOR activity is independently associated with hypertension in nondiabetic individuals who are not taking any medications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Hyperuricemia often occurs concomitantly with metabolic syndrome, hypertension, chronic kidney disease, and cardiovascular disease [1]. However, it has been reported that both high and low serum levels of uric acid are associated with chronic kidney disease [2,3,4] and cardiovascular disease [5, 6]. A recent umbrella review including meta-analyses of observational studies, randomized controlled trials and Mendelian randomization analyses showed that convincing evidence of a clear role of serum uric acid level only exists for gout and nephrolithiasis [7]. Therefore, uric acid has been suggested to be a mere biomarker, not a true risk factor, for renal and cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension [7, 8]. It has been proposed that other urate-related factors, including xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) and intracellular uric acid, but not serum extracellular uric acid, are possible true risk factors [8].

XOR is a catalyzing and rate-limiting enzyme of uric acid production by oxidative hydroxylation of hypoxanthine and xanthine in purine metabolism [8, 9]. XOR is transcribed and translated as xanthine dehydrogenase (XDH) and can be posttranslationally converted to xanthine oxidase (XO) [8, 9]. XDH reduces NAD+ to NADH, and XO consumes oxygen to produce hydrogen peroxide and superoxide [8, 9]. Therefore, activation of XOR can be a source of reactive oxygen species, leading to oxidative stress-induced injury in several tissues [10, 11]. However, measurement of plasma XOR activity has been difficult because of very low XOR activity in humans [12]. An accurate method for measuring plasma XOR activity in humans has recently been developed using liquid chromatography and triple quadrupole mass spectrometry [13]. Using this method, we and others have recently shown that plasma XOR activity is independently associated with obesity, smoking, liver dysfunction, hyperuricemia, dyslipidemia, insulin resistance, and adipokines, suggesting that plasma XOR activity might be a new metabolic biomarker [14,15,16,17,18,19].

It has recently been reported that plasma XOR activity was associated with hypertension in 156 Japanese subjects (male/female: 68/88) who received health examinations to check the status of lifestyle-related diseases, including hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, visceral obesity, hyperuricemia, atherosclerosis, and cerebrovascular disease [20]. However, although subjects treated with antihypertensive or antihyperuricemic drugs were excluded [20], the recruited subjects might have been treated for other comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and heart disease, in which increases in plasma XOR activity have been reported [15, 21]. It is still unclear whether elevated XOR activity contributes to blood pressure elevation prior to exerting its significant impact on the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus and/or cardiovascular and renal dysfunction. Therefore, the association between plasma XOR activity and hypertension has not been fully addressed. We therefore investigated the link between plasma XOR activity and hypertension in a general population allowing for the exclusion of drug effects and the effects of diabetes mellitus.

Methods

Study subjects

In a population-based cohort, the Tanno–Sobetsu Study, a total of 627 Japanese subjects (male/female: 292/335) who received annual health examinations in 2016 were recruited. This population was the same as that analyzed in our previous study investigating plasma XOR activity [15]. Subjects who were being treated with any medications and subjects with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥6.5% were excluded to eliminate the effects of drugs on plasma XOR activity and the effects of diabetes mellitus. A total of 271 subjects (male/female: 119/152) were enrolled in the present study. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Sapporo Medical University (number: H24-7-30) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all of the study subjects.

Measurements

Medical check-ups were performed in the early morning after an overnight fast as previously described [15]. Blood pressure was measured twice consecutively on the upper arm using an automated sphygmomanometer (HEM-907, Omron Co., Kyoto, Japan), and average blood pressure was used for analysis. Body mass index was calculated as body weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of body height (in meters). Variables of liver function, renal function, and glucose and lipid metabolism were measured as previously described [15]. Estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was calculated using an equation for Japanese individuals [22]. As an index of insulin resistance, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) was calculated as glucose (mg/dL) × insulin (μU/mL)/405 [23]. HbA1c was expressed on the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP) scale. Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) was measured using an assay kit (Shionogi & Co., Osaka, Japan).

Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90 mmHg. Dyslipidemia was defined as LDL cholesterol ≥140 mg/dL, HDL cholesterol <40 mg/dL or triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL. Hyperuricemia was defined as uric acid >7 mg/dL.

Plasma XOR activity

Plasma XOR activity was measured by using a combination of liquid chromatography and triple quadrupole mass spectrometry to detect [13C2, 15N2]-uric acid using [13C2, 15N2]-xanthine as a substrate as previously reported [13, 15]. The inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation were 9.1% and 6.5%, respectively, and the lower limit of detection was 6.67 pmol/h/mL plasma [13].

Statistical analysis

Numerical parameters are expressed as the means ± SDs for normal distributions or medians (interquartile ranges) for skewed variables. The normality of the distribution for each variable was tested by the Shapiro–Wilk W test. Comparisons of parametric and nonparametric parameters between the two groups were performed by using Student’s t-test and the Mann–Whitney U test, respectively. The chi-square test was performed for intergroup differences in percentages of parameters. Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to assess correlations between two variables. Nonnormally distributed variables were logarithmically transformed for regression analyses. Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed in several models to identify independent determinants of the risk of hypertension using age, sex, current smoking habit, and variables with a significant difference between subgroups divided by the absence and presence of hypertension as independent predictors after consideration of multicollinearity, showing the odds ratio (OR), 95% confidence interval (CI) and Akaike’s information criterion (AIC). The interaction between sex and plasma XOR activity for the risk of hypertension was also investigated. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analyzed by using JMP15.2.1 for Macintosh (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

Baseline characteristics of the study subjects

Baseline characteristics of the recruited nondiabetic subjects who had not been taking any medications grouped according to the absence and presence of hypertension into a non-HT group (n = 197, males/female: 85/112) and HT group (n = 74, male/female: 34/40) are shown in Table 1. Subjects in the HT group were significantly older and had significantly greater body mass index and waist circumference values; significantly higher levels of mean arterial pressure, systolic and diastolic blood pressures, aspartate transaminase (AST), alanine transaminase (ALT), fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA-IR, HbA1c, and BNP; and significantly lower levels of eGFR than subjects in the non-HT group. There was no significant difference in uric acid levels between the non-HT and HT groups.

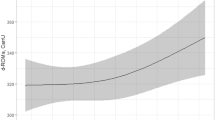

Plasma XOR activity was significantly higher in the HT group than in the non-HT group (median: 39 vs. 28 pmol/h/mL plasma, P = 0.028) (Fig. 1). In all of the subjects, males had significantly higher plasma XOR activity than females (median: 40 vs. 25 pmol/h/mL plasma, P = 0.001) (Supplementary Fig. 1A). When the subjects were divided by sex, plasma XOR activity was significantly higher in the HT group than in the non-HT group in males (median: 57 vs. 33 pmol/h/mL plasma, P = 0.020), but XOR activity was not significantly higher in the HT group than in the non-HT group in females (median: 33 vs. 23 pmol/h/mL plasma, P = 0.272) (Supplementary Fig. 1B, C).

Plasma XOR activity in subjects with and without hypertension. Comparison of plasma xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) activity in the absence and presence of hypertension shown by box plots: non-HT (male/female: 85/112) and HT (male/female: 34/40) groups. A comparison of the nonparametric parameter between the two groups was performed by using the Mann–Whitney U test. *P < 0.05

Correlations of plasma XOR activity with various parameters

The correlations of plasma XOR activity with various parameters are shown in Supplementary Table 1. There were strong positive correlations of plasma XOR activity with the levels of liver enzymes, AST (r = 0.540, P < 0.001) and ALT (r = 0.728, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2A). Plasma XOR activity was positively correlated with mean arterial pressure (r = 0.128, P = 0.036) (Fig. 2B) and diastolic blood pressure (r = 0.132, P = 0.030) (Fig. 2C) but not with systolic blood pressure (r = 0.101, P = 0.098) (Fig. 2D).

Correlations of plasma XOR activity with various parameters. A–D Logarithmically transformed (log) alanine transaminase (ALT), mean arterial pressure (B), diastolic blood pressure (C) and systolic blood pressure (D) were plotted against log plasma xanthine oxidoreductase (XOR) activity in each subject (n = 271, male/female: 119/152). Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to assess correlations between two variables. Nonnormally distributed variables and logarithmically transformed nonparametric parameters were used for regression analyses. Open circles: males, closed circles: females

Associations between plasma XOR activity and the presence of hypertension

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that plasma XOR activity (OR: 1.093 [95% CI: 1.030–1.173] per 10 pmol/h/mL plasma, P = 0.003) was an independent determinant of the risk for hypertension after adjustment for age and sex (Model 1, AIC: 274) (Table 2). There was no significant interaction between sex and plasma XOR activity in regard to the risk of hypertension (P = 0.906). When eGFR, BNP and body mass index were additionally incorporated into Model 1, plasma XOR activity became a significant risk factor for hypertension (OR: 1.069 [95% CI: 1.005–1.148] per 10 pmol/h/mL plasma, P = 0.034) (Model 2, AIC: 263). When eGFR, BNP, and HOMA-IR were additionally incorporated into Model 1, plasma XOR activity remained a significant risk factor for hypertension (OR: 1.080 [95% CI: 1.015–1.161] per 10 pmol/h/mL plasma, P = 0.015) (Model 3, AIC: 257). When habits of current smoking and alcohol consumption were additionally incorporated into Model 3, plasma XOR activity was a significant independent risk factor for hypertension, with the minimum AIC among the models (OR: 1.091 [95% CI: 1.023–1.177] per 10 pmol/h/mL plasma, P = 0.007) (Model 4, AIC: 237).

Discussion

The present study showed that plasma XOR activity in the HT group was significantly higher than that in the non-HT group and that high plasma XOR activity was an independent risk factor for hypertension after adjustment for age, sex, habits of current smoking and alcohol consumption, eGFR, BNP, and HOMA-IR in nondiabetic subjects who had not taken any medications. There were weak positive, but statistically significant, correlations of plasma XOR activity with mean arterial pressure (r = 0.128, P = 0.036) and diastolic blood pressure (r = 0.132, P = 0.030), although no significant correlation between plasma XOR activity and systolic blood pressure was found in the present study. Rather than a direct association of plasma XOR activity with blood pressure at a certain time point, a continuous condition of high plasma XOR activity may contribute to the risk of hypertension.

Plasma XOR activity was previously reported to be associated with high blood pressure in 156 Japanese subjects (male/female: 68/88) in a health examination registry who were not receiving treatment with antihypertensive or antihyperuricemic drugs [20]. However, there might have been subjects who were being treated for other comorbidities, including diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and heart disease, which can lead to an increase in plasma XOR activity [15, 21]. In the present study, we showed the association between plasma XOR activity and hypertension independent of insulin resistance in 271 nondiabetic subjects (male/female: 119/152) who had not been taking any medications to eliminate the effects of diabetes mellitus and drugs on plasma XOR activity. When the subjects were divided by sex, plasma XOR activity was significantly higher in the HT group than in the non-HT group in males but was not significantly higher in females (Supplementary Fig. 1). The relatively small number of females included might have led to the insufficiently significant results in females since there was no significant interaction of plasma XOR activity with sex for the risk of hypertension (Table 2). Along with the results of a previous study [20], these findings suggest that plasma XOR activity contributes to blood pressure elevation in hypertensive patients with and without comorbidities, including insulin resistance and diabetes mellitus.

There are several possible mechanisms of the association between plasma XOR activity and hypertension. XOR is expressed in the XDH form in tissues, and it leaks into blood and consequently converts to the XO form [24, 25]. XO is shed into plasma by an organ without nonspecific membrane damage and is partially bound to sulfated glycosaminoglycans on the surface of vascular endothelial cells [10, 11]. It has been reported that activation of endothelium-bound XOR can inhibit endothelial nitric oxide production and impair vasodilatory reactions [26]. It has also been reported that plasma XOR activity is independently associated with adipokines and hepatokines [16]. A change in XOR activity was also shown to be significantly associated with changes in liver enzymes and body weight [17]. Inadequate activation of XOR may promote oxidative stress-related tissue injury, including injury to endothelial cells and the kidney [8], possibly leading to elevated blood pressure.

In the present study, plasma XOR activity was found to be strongly associated with the levels of liver enzymes, as previously reported [15, 17]. The liver has been reported to be a main source of plasma XOR [8, 15]. Therefore, levels of liver enzymes were not included in logistic regression analyses for the risk of hypertension because of the consideration of multicollinearity with plasma XOR activity in the present study. It has recently been reported that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is associated with the development of hypertension [27,28,29]. Several possible mechanisms of the association between chronic liver disease and hypertension, including dysregulation of the renin–angiotensin system [30], insulin resistance [31], chronic inflammation [32], and liver-derived proinflammatory, profibrogenic, and antifibrinolytic molecules called hepatokines [33], have been reported. Liver dysfunction-related activation of plasma XOR activity may also be one of the risk factors for hypertension.

Previous genetic studies on urate transporters and Mendelian randomization studies failed to demonstrate a causal relationship between serum uric acid and hypertension [7, 34, 35]. However, most of the studies used genes related to the uptake and secretion of uric acid but not genes related to the production of uric acid [7, 8, 34, 35]. It has been reported that variation in uric acid production, as captured by XOR genetic polymorphisms, is a predictor of changes in blood pressure and the risk of hypertension [36]. These observations suggest that XOR in the urate production pathway, rather than urate uptake and secretion pathways in the regulation of serum uric acid levels, is relevant to the development of hypertension.

Xanthinuria caused by XOR deficiency is a rare disease in humans, and most patients with diagnosed xanthinuria have no documentation of hypertension [37]. To the best of our knowledge, there was one case report of a 3-year-old female patient with xanthinuria causing xanthine stones, obstructive uropathy and hypertension [38]. Her blood pressure was elevated at 130/90 mmHg, and her blood pressure had decreased to 80/60 mmHg at 8 months after nephrectomy for obstructive uropathy due to xanthine stones [38]. Previous findings suggest that XOR deficiency itself protects against the development of hypertension, although xanthine stones may cause elevation of blood pressure due to obstructive uropathy-induced renal dysfunction.

There have been some intervention studies on the effects of XOR inhibitors, including allopurinol, febuxostat, and topiroxostat, in hypertensive patients with hyperuricemia, and blood pressure was shown to mildly decrease in some studies [39,40,41]. Inhibition of plasma XOR activity may contribute to the regulation of blood pressure beyond urate-lowering effects. A previous study using mice showed that the 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) value in plasma by topiroxostat was lower than that by febuxostat, although the IC50 values of both drugs were almost the same in the liver and kidney [42]. The inhibitory potency of allopurinol was the weakest in each mouse tissue [42]. Furthermore, it has been reported that the IC50 value of topiroxostat is lower than that of febuxostat and that of oxipurinol, a metabolite of allopurinol in a mixture of human plasma and liver [43]. In a previous study of 135 hypertensive patients with hyperuricemia, treatment with either topiroxostat or febuxostat for 24 weeks mildly, but significantly, decreased systolic blood pressure (−8.6 mmHg vs. −6.3 mmHg), which was accompanied by a similar reduction of uric acid levels, although there was no significant change in cardio-ankle vascular index (CAVI), a marker of arterial stiffness reflecting effects on smooth muscle cells more than endothelial cells [41]. Interestingly, regarding possible pleiotropic effects, treatment with topiroxostat, but not that with febuxostat, significantly decreased plasma XOR activity and urinary albumin–creatinine ratio compared with levels at baseline [41], suggesting that inhibition of plasma XOR activity prevents renal damage beyond reduction in blood pressure and uric acid levels. It has also been reported that treatment with topiroxostat for 8 weeks significantly increased brachial artery flow-mediated dilation (FMD) on ultrasonography, indicating an improvement in vascular endothelial function [44]. The improvement of endothelial function resulting from inhibition of plasma XOR activity may also contribute to the lowering of blood pressure. Adequate inhibition of plasma XOR activity unless uric acid levels are lowered might be a new therapeutic strategy for the treatment of hypertension and its related diseases.

This study has some limitations. First, the results of the present study do not prove causal relations between plasma XOR activity and hypertension because the study was a cross-sectional study. Longitudinal studies need to be performed to clarify the association between plasma XOR activity and the development of hypertension. Second, since only Japanese people were enrolled, the results of the present study might not be applicable to other races. Third, the level of uric acid in urine was not investigated, and the balance of production and excretion of uric acid was not analyzed in the present study. Since, it has been reported that intracellular uric acid is associated with oxidative stress independent of XOR, leading to cellular damage, including damage to endothelial cells [8, 45], further intervention investigations are necessary to investigate which type of drugs to treat hyperuricemia, XOR inhibitors or uricosuric agents, are better for the prevention of several urate-associated diseases, including hypertension. Last, measurements of plasma XOR activity vary among laboratories. Values of plasma XOR activity are not comparable to those measured in other laboratories using different assay protocols.

In conclusion, plasma XOR activity is independently associated with the risk for hypertension in nondiabetic individuals who are not taking any medications. A further understanding of the association between plasma XOR activity and hypertension may enable the development of novel therapies for hypertension and its related metabolic and cardiovascular diseases.

References

Feig DI, Kang DH, Johnson RJ. Uric acid and cardiovascular risk. N. Engl J Med. 2008;359:1811–21.

Mori K, Furuhashi M, Tanaka M, Numata K, Hisasue T, Hanawa N, et al. U-shaped relationship between serum uric acid level and decline in renal function during a 10-year period in female subjects: BOREAS-CKD2. Hypertens Res. 2021;44:107–16.

Wakasugi M, Kazama JJ, Narita I, Konta T, Fujimoto S, Iseki K, et al. Association between hypouricemia and reduced kidney function: a cross-sectional population-based study in Japan. Am J Nephrol. 2015;41:138–46.

Zhu P, Liu Y, Han L, Xu G, Ran JM. Serum uric acid is associated with incident chronic kidney disease in middle-aged populations: a meta-analysis of 15 cohort studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e100801.

Verdecchia P, Schillaci G, Reboldi G, Santeusanio F, Porcellati C, Brunetti P. Relation between serum uric acid and risk of cardiovascular disease in essential hypertension. The PIUMA study. Hypertension 2000;36:1072–8.

Zhang W, Iso H, Murakami Y, Miura K, Nagai M, Sugiyama D, et al. Serum uric acid and mortality form cardiovascular disease: EPOCH-JAPAN study. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2016;23:692–703.

Li X, Meng X, Timofeeva M, Tzoulaki I, Tsilidis KK, Ioannidis JP, et al. Serum uric acid levels and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of evidence from observational studies, randomised controlled trials, and Mendelian randomisation studies. BMJ 2017;357:j2376.

Furuhashi M. New insights into purine metabolism in metabolic diseases: role of xanthine oxidoreductase activity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2020;319:E827–E34.

Nishino T, Okamoto K. Mechanistic insights into xanthine oxidoreductase from development studies of candidate drugs to treat hyperuricemia and gout. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2015;20:195–207.

Battelli MG, Bolognesi A, Polito L. Pathophysiology of circulating xanthine oxidoreductase: new emerging roles for a multi-tasking enzyme. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1842:1502–17.

Kelley EE. A new paradigm for XOR-catalyzed reactive species generation in the endothelium. Pharm Rep. 2015;67:669–74.

Parks DA, Granger DN. Xanthine oxidase: biochemistry, distribution and physiology. Acta Physiol Scand Suppl. 1986;548:87–99.

Murase T, Nampei M, Oka M, Miyachi A, Nakamura T. A highly sensitive assay of human plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity using stable isotope-labeled xanthine and LC/TQMS. J Chromatogr B Anal Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2016;1039:51–8.

Washio KW, Kusunoki Y, Murase T, Nakamura T, Osugi K, Ohigashi M, et al. Xanthine oxidoreductase activity is correlated with insulin resistance and subclinical inflammation in young humans. Metabolism 2017;70:51–6.

Furuhashi M, Matsumoto M, Tanaka M, Moniwa N, Murase T, Nakamura T, et al. Plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity as a novel biomarker of metabolic disorders in a general population. Circ J. 2018;82:1892–9.

Furuhashi M, Matsumoto M, Murase T, Nakamura T, Higashiura Y, Koyama M, et al. Independent links between plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity and levels of adipokines. J Diabetes Investig 2019;10:1059–67.

Furuhashi M, Koyama M, Matsumoto M, Murase T, Nakamura T, Higashiura Y, et al. Annual change in plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity is associated with changes in liver enzymes and body weight. Endocr J. 2019;66:777–86.

Furuhashi M, Mori K, Tanaka M, Maeda T, Matsumoto M, Murase T, et al. Unexpected high plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity in female subjects with low levels of uric acid. Endocr J. 2018;65:1083–92.

Furuhashi M, Koyama M, Higashiura Y, Murase T, Nakamura T, Matsumoto M, et al. Differential regulation of hypoxanthine and xanthine by obesity in a general population. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11:878–87.

Yoshida S, Kurajoh M, Fukumoto S, Murase T, Nakamura T, Yoshida H, et al. Association of plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity with blood pressure affected by oxidative stress level: MedCity21 health examination registry. Sci Rep. 2020;10:4437.

Otaki Y, Watanabe T, Kinoshita D, Yokoyama M, Takahashi T, Toshima T, et al. Association of plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity with severity and clinical outcome in patients with chronic heart failure. Int J Cardiol. 2017;228:151–7.

Matsuo S, Imai E, Horio M, Yasuda Y, Tomita K, Nitta K, et al. Revised equations for estimated GFR from serum creatinine in Japan. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:982–92.

Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, Turner RC. Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta-cell function from fasting plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 1985;28:412–9.

Amaya Y, Yamazaki K, Sato M, Noda K, Nishino T, Nishino T. Proteolytic conversion of xanthine dehydrogenase from the NAD-dependent type to the O2-dependent type. Amino acid sequence of rat liver xanthine dehydrogenase and identification of the cleavage sites of the enzyme protein during irreversible conversion by trypsin. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14170–5.

Battelli MG, Abbondanza A, Stirpe F. Effects of hypoxia and ethanol on xanthine oxidase of isolated rat hepatocytes: conversion from D to O form and leakage from cells. Chem Biol Interact. 1992;83:73–84.

Houston M, Estevez A, Chumley P, Aslan M, Marklund S, Parks DA, et al. Binding of xanthine oxidase to vascular endothelium. Kinetic characterization and oxidative impairment of nitric oxide-dependent signaling. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:4985–94.

Huh JH, Ahn SV, Koh SB, Choi E, Kim JY, Sung KC, et al. A prospective study of fatty liver index and incident hypertension: the KoGES-ARIRANG study. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0143560.

Bonnet F, Gastaldelli A, Pihan-Le Bars F, Natali A, Roussel R, Petrie J, et al. Gamma-glutamyltransferase, fatty liver index and hepatic insulin resistance are associated with incident hypertension in two longitudinal studies. J Hypertens. 2017;35:493–500.

Roh JH, Park JH, Lee H, Yoon YH, Kim M, Kim YG, et al. A close relationship between non-alcoholic fatty liver disease marker and new-onset hypertension in healthy korean adults. Korean Circ J. 2020;50:695–705.

Matthew Morris E, Fletcher JA, Thyfault JP, Rector RS. The role of angiotensin II in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2013;378:29–40.

da Silva AA, do Carmo JM, Li X, Wang Z, Mouton AJ, Hall JE. Role of hyperinsulinemia and insulin resistance in hypertension: metabolic syndrome revisited. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:671–82.

Rivera CA. Risk factors and mechanisms of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. Pathophysiology 2008;15:109–14.

Meex RCR, Watt MJ. Hepatokines: linking nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and insulin resistance. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2017;13:509–20.

Major TJ, Dalbeth N, Stahl EA, Merriman TR. An update on the genetics of hyperuricaemia and gout. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14:341–53.

Gill D, Cameron AC, Burgess S, Li X, Doherty DJ, Karhunen V, et al. Urate, blood pressure, and cardiovascular disease: evidence from mendelian randomization and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Hypertension 2021;77:383–92.

Scheepers LE, Wei FF, Stolarz-Skrzypek K, Malyutina S, Tikhonoff V, Thijs L, et al. Xanthine oxidase gene variants and their association with blood pressure and incident hypertension: a population study. J Hypertens. 2016;34:2147–54.

Ichida K, Amaya Y, Okamoto K, Nishino T. Mutations associated with functional disorder of xanthine oxidoreductase and hereditary xanthinuria in humans. Int J Mol Sci. 2012;13:15475–95.

Maynard J, Benson P. Hereditary xanthinuria in 2 Pakistani sisters: asymptomatic in one with beta-thalassemia but causing xanthine stone, obstructive uropathy and hypertension in the other. J Urol. 1988;139:338–9.

Sanchez-Lozada LG, Rodriguez-Iturbe B, Kelley EE, Nakagawa T, Madero M, Feig DI, et al. Uric acid and hypertension: an update with recommendations. Am J Hypertens. 2020;33:583–94.

Piani F, Cicero AFG, Borghi C. Uric acid and hypertension: prognostic role and guide for treatment. J Clin Med. 2021;10:448.

Kario K, Nishizawa M, Kiuchi M, Kiyosue A, Tomita F, Ohtani H, et al. Comparative effects of topiroxostat and febuxostat on arterial properties in hypertensive patients with hyperuricemia. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2021;23:334–44.

Nakamura T, Murase T, Nampei M, Morimoto N, Ashizawa N, Iwanaga T, et al. Effects of topiroxostat and febuxostat on urinary albumin excretion and plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity in db/db mice. Eur J Pharm. 2016;780:224–31.

Nakamura T, Murase T, Satoh E, Miyachi A, Ogawa N, Abe K, et al. The influence of albumin on the plasma xanthine oxidoreductase inhibitory activity of allopurinol, febuxostat and topiroxostat: Insight into extra-urate lowering effect. Integrative. Mol Med. 2019;6:1–7.

Higa S, Shima D, Tomitani N, Fujimoto Y, Kario K. The effects of topiroxostat on vascular function in patients with hyperuricemia. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2019;21:1713–20.

Maruhashi T, Hisatome I, Kihara Y, Higashi Y. Hyperuricemia and endothelial function: from molecular background to clinical perspectives. Atherosclerosis 2018;278:226–31.

Acknowledgements

MF was supported by a grant from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

TM, TN, and SA in Sanwa Kagaku Kenkyusho Co., Ltd. developed the plasma XOR activity assay and measured the activity. This does not alter our adherence to sharing data and materials. There are no competing nonfinancial interests for any authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Furuhashi, M., Higashiura, Y., Koyama, M. et al. Independent association of plasma xanthine oxidoreductase activity with hypertension in nondiabetic subjects not using medication. Hypertens Res 44, 1213–1220 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00679-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41440-021-00679-1

Keywords

This article is cited by

-

An increase in calculated small dense low-density lipoprotein cholesterol predicts new onset of hypertension in a Japanese cohort

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease is associated with an increase in systolic blood pressure over time: linear mixed-effects model analyses

Hypertension Research (2023)

-

Association of serum xanthine oxidase levels with hypertension: a study on Bangladeshi adults

Scientific Reports (2022)

-

Serum uric acid level is associated with an increase in systolic blood pressure over time in female subjects: Linear mixed-effects model analyses

Hypertension Research (2022)

-

Impact of hyperuricemia on chronic kidney disease and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease

Hypertension Research (2022)