Abstract

Over the past three decades, billions have been invested in community policing to foster positive interactions between officers and community members. Yet, public trust in police continues to decline. Our qualitative analysis of over 500 hours of naturalistic observations suggests a potential reason: the questioning styles of officers in community policing may make community members feel threatened. Observations also point to a solution: transparent communication of benevolent intent. Building on this, a pre-registered field experiment (N = 232) finds that community members feel less threatened and report greater trust when officers use a brief transparency statement (e.g., “I’m walking around trying to get to know the community”). These findings are supported by exploratory natural language processing and sympathetic nervous system measures. Six online experiments (total N = 3210) further show that transparency statements are effective across diverse groups and isolate the conditions where they work best. This multi-method investigation underscores the importance of transparency in fostering positive community-police relations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Since 1994, the U.S. federal government has invested more than $14 billion in more than 13,000 law enforcement agencies to support community policing efforts1. In community policing, officers are asked to prevent crimes by centering decision-making within the community. Officers question community members, solve community problems, and cultivate cooperative relationships, even when they are not actively interrogating a suspect in a potential crime2,3. By 2013, 90% of medium-to-large police departments in the U.S. claimed to be using community policing to at least some extent, although these approaches remain unstandardized4.

Community policing, on its face, appears to be a more respectful approach than the proactive policing model. In contrast to community policing, proactive policing typically involves an investigatory stop, in which police intrusively question people (e.g., “What are you doing here?”), pat them down, search them, or handcuff them when suspected of illicit activity5. One well-known manifestation of this is the “stop and frisk” policy adopted in New York City in the 1990s6. Proactive policing is a widespread approach intended to reduce violent crimes, but it has a high cost. It is a major contributor to the escalation of interactions that end in accusations of wrongful arrest or police brutality—particularly for historically over-policed communities of color and those from lower socioeconomic contexts or neighborhoods7.

Although community policing has the potential to repair trust between communities and law enforcement, the approach has so far been largely ineffective. Empirical evaluations show no average reduction in crime and no increase in citizens’ trust in the benevolence of police8. This is especially true in historically over-policed communities, such as those with higher proportions of civilians of color, where trust in law enforcement is much lower on average9,10,11. Indeed, despite the prevalence of community policing initiatives, the public’s trust as a whole in the legitimacy of law enforcement has still experienced a precipitous decline and is now at an all-time low12,13. This loss of trust and legitimacy, in turn, makes citizens more hostile to police and less likely to comply with officers’ requests for the information they need to solve a case—all of which make society less safe from harm14.

Interestingly, the effects of strategies classified as community policing—though not positive and significant on average—are highly heterogeneous. A systematic review and meta-analysis8 found that several studies showed significant benefits in line with policymakers’ expectations15. However, several studies showed significant increases in crime and reductions in trust, contrary to the aims of the approach16. Furthermore, scholars have noted that law enforcement agencies claiming to implement community policing are often referring to very different practices17. This raises the possibility that it is not community policing itself, but rather something about how it is implemented, that accounts for the inconsistent results in prior evaluation studies.

Our research begins with the observation that the mere presence of a police officer elicits threat responses in community members: people are faster to avoid, they freeze more, and they are more startled when exposed to a police officer (vs. non-police officer) stimulus18. This is, in part, because community members have learned to fear that officers are accusing them of a crime and are likely to search or handcuff them during an interaction19,20 (see Methods section for a pilot study corroborating the idea that community members typically feel threatened upon being approached by a police officer).

Importantly, officers have discretion over their conversational dynamics, meaning they could speak in ways that would assuage community members’ concerns. However, officers often fail to leverage their discretion in a way that builds trust. One qualitative study of police officers during ride-alongs (i.e., routine officer patrols attended by researchers19) found that civilians with whom officers were interacting worried that they were being approached for enforcement reasons. In part, this was because patrol officers continued to use aggressive questioning methods that were tailored for suspects (e.g., “What are you doing here? How long have you been here? Where are you going next?”)—even when officers were attempting to cultivate trusting relationships with community members. That study19 furthermore found that community members perceived officers’ interest in them as harassment. As a result, community members anxiously tried to disengage from the conversation from the start, only to feel increasingly threatened as the interaction proceeded. Officers in turn perceive attempts at disengagement or evasion as a suspicious sign that the community member has something criminal to hide. This leads officers to escalate their tactics to interrogate or control community members, resulting in unnecessary arrests or physical harm. The result is a negative cycle of threat that undermines the goals of building trust, even when officers’ initial intent might have been positive.

Here, in a mixed-methods investigation, we show that police officers can implement our intervention method—what we term a transparency statement—with fidelity even with brief training. We further show that transparency statements reliably decrease community members’ sense of threat and increase their trust in live community policing interactions. Moreover, our results suggest that transparency statements have benefits even for those members of groups that have been historically over-policed (i.e., people of color and those from lower socioeconomic contexts).

Results

Hypothesis generation via qualitative field observations

Building on the prior qualitative work revealing that civilians were worried that they were being approached by officers for enforcement reasons19, we collected new ethnographic data to generate hypotheses about how to disrupt or even reverse the negative cycle of interactions that seem to undermine community policing. We conducted over 500 hours of field observations, interviews, and ride-alongs with police officers in law enforcement agencies in a diverse metropolitan area in the U.S. (see Table 1). Field notes were written in shorthand and subsequently expanded upon soon after the observations. After field notes were transcribed, the two lead authors discussed themes, using past literature to make sense of what was being observed. Following standard practices for analyzing qualitative data21, the lead authors iteratively observed and discussed observations until thematic saturation was reached, which is the analytic process typically used for ethnographic, grounded theory research.

Observations came from two units of police officers, chosen to collectively reflect the heterogeneity in the effectiveness of community policing tactics8. One was a traditional patrol unit and another was a unit implementing a pilot program designed to build relationships with the community. In both units, the authors observed interactions that were initiated with benevolent intent, in which officers were genuinely attempting to build relationships with their communities. Critically, the two units differed in the tactics they employed to achieve this goal. Some officers peppered community members with questions (e.g., “What are you guys doing here?”, “What are you up to?”), largely consistent with proactive policing tactics5. When we interviewed community members after those interactions, citizens described feeling threatened, uncertain if they were going to be accused of a crime and confused as to why the officers chose to talk with them (see left panel in Table 1). Other officers, by contrast, were transparent. From the outset, they explained that their department had a new community policing initiative, and that their job was to get to know the community. Interactions between these officers and community members proceeded very differently. Community members appeared at ease and willing to talk with these officers (see right panel in Table 1; see Supplementary Methods E).

Our preliminary qualitative observations led us to generate a quantitative hypothesis about how to intervene to improve police-community interactions (Fig. 1A). We theorized that when, from the outset of the interaction, the officer stated transparently that their questioning was not coming from a proactive policing model, but rather from a community policing model, this might put the community member at ease and evoke positive engagement. Importantly, because the first words in a conversation set the stage for everything that follows, if officers briefly clarified from the start what their positive goal is, it could prevent an escalating threat that has an outsized effect on the ultimate outcomes of the interaction.

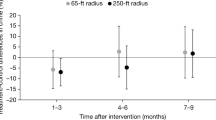

A The three phases of the present research, B The behavioral study procedures, and C average treatment effects (ATEs) of the transparency statement in the behavioral study (N = 232). Note: * = pre-registered, confirmatory outcome. ATE average (i.e., mean) treatment effect. EDA electrodermal activity, which assessed sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation (see Fig. 3). B The non-seeing eye represents assignment of community member participants to experimental condition, with the participants and experimenters both kept unaware of condition assignment. Officers were aware of condition assignment because they delivered the manipulation verbally, but study hypotheses were not shared with them. Participants recruited for the study were seated with the sensors during a baseline period, told to act as they naturally would while sitting outside by themselves. Participants did not know when or who they would be approached by but were told the sensors would monitor them during any interactions they had while in the study. C ATEs calculated in a Bayesian Causal Forest model that used a machine-learning approach with conservative BART priors; covariates were age, race/ethnicity, gender, education level, and English language proficiency of community members. Thick bars represent the inter-quartile range (IQR) of the posterior distribution of treatment effects, and thin bars depict the 10th to the 90th percentiles. Statistical tests for the final outcome—inspiration—appear in the SI. See the SI for results of conventional null hypothesis tests. Designed by Freepik, http://www.freepik.com/.

We call this a transparency statement. It involves a clear and truthful statement of the officer’s benevolent intent for the interaction at the outset. Concretely, for example, it is the difference between an officer stating “Hi, I’m Officer [Name], how’s it going? Can I talk to you for a minute?” which is not transparent but is the default for many officers, and an officer adding the ten-word statement “I’m walking around trying to get to know the community” before asking to talk with the person, which is transparent. See Fig. 1B. Note that without the transparency statement, the community member is free to assume that the officer’s intentions are to repeat the past: aggressively interrogate a suspected criminal22,23. But with the transparency statement, the officer has presumably not left their intentions open to a negative alternative interpretation that could erode trust.

Emerging from this qualitative work, one prominent theory justified our hypothesis that a transparency statement could improve community-police relations. This is procedural justice (PJ) theory, which is a prominent framework for explaining the conditions under which people come to view authority figures like police as legitimate24. A key tenet of theory on PJ is that how community members are treated during interactions will affect their perceptions of and attitudes towards the police (e.g., trust) over and above the outcomes of the interactions. In particular, a crucial component of the PJ framework is that when police communicate trustworthy motives, community members will view police as legitimate and be more likely to cooperate with police even if the overall outcome of the interaction is negative (e.g. ending in arrest). Thus, PJ theory supports the hypothesis that a transparency statement will build trust between police and their communities. This is because a transparency statement involves an officer making their benevolent intentions clear from the start of an interaction.

Although the transparency hypothesis is consistent with the tenets of PJ theory, our research is also a contribution to the literature on PJ theory. This is because the current literature does not provide specific and concrete ways for officers to communicate trustworthy motives in their everyday interactions. If research could show that a short transparency statement was effective at increasing trust in community-police interactions, it would be a contribution because it could help to explain why programs inspired by PJ theory in real-world settings have led to mixed results24,25,26,27 with a high degree of unexplained heterogeneity (I2 = 95%; see also Supplementary Methods C and Supplementary Data 1)28. This high degree of unexplained heterogeneity suggests that research has not yet illuminated which contextual features predict whether PJ treatments will yield their intended effects (e.g., the type of interactions being studied). One reason why PJ programs might be inconsistently effective is because they did not specify, concretely, how officers might best communicate trustworthy motives. Instead, PJ programs have typically involved training officers on all the many different elements of PJ theory while also giving officers discretion in how to implement the recommendations. Thus, a key contribution of our bottom-up approach is to identify the potential impact of the precise language officers might use to communicate trustworthy motives in their interactions with the community.

Naturalistic experiment in the field with live interactions

Next, we report a pre-registered, blinded, controlled naturalistic experiment in the field that directly tested the causal effect of a transparency statement in live interactions between a community member and a uniformed officer. Note that this experiment was critical for establishing the basic effects of transparency statements using precise experimental methods, where location and time of day were controlled. This experimental control allowed the study to examine causality while retaining natural realism (i.e., participants did not know they would be approached by a uniformed officer genuinely interested in building rapport). The controlled location also allowed us to position equipment to record the conversations. Finally, without preemptively consenting and setting community members up in the experiment, we would not have been able to outfit participants with the psychophysiological and audio recording measures that allowed us to assess arousal and natural language. See Table 2 for a detailed breakdown of the field study criteria29,30 our study fulfilled. A possible limitation of the design is that the process of obtaining active informed consent could have changed the civilians’ behaviors relative to a study in which participants were fully blinded from their participation. As such, the experiment presented here was a precursor to a future program of field research (not reported here) that could test the longer-term effects of transparency on public safety (which would afford less experimental control).

In Experiment 1, N = 232 adults who lived in a community known for recent accusations of officers’ mistreatment and use of excessive force were told that we were studying natural interpersonal interactions and outfitted them with ambulatory physiological sensors. They were not told who they would interact with, or when. Participants were soon approached by a fully-uniformed officer carrying a weapon and asked questions for 1–2 minutes (self-reported demographics: Mage = 22.07, SDage = 5.90; 54% female, 41% male, 4% non-binary/other gender identity; 30% held a four-year college degree; 33% identified as White/European American; 33% as Asian/Asian American; 17% as Latinx/Hispanic American; 9% as Black/African American; 8% as other). We primarily recruited young adults because this age group is more likely to have adversarial interactions with police officers compared to older adults4,31,32, and therefore we suspected they would benefit from transparency. The study design is depicted in Fig. 1B. Officers were asked to have a conversation with a community member like they typically would when engaging in community policing activities. Half of the time the officer added a transparency statement (described above; see Table 3 for examples) when they introduced themselves, and half of the time they did not. The instructions given to officers did not differ in any other way and officers were not told the study hypotheses or outcomes. Demonstrating the equivalence between the groups, officers in the transparency condition were not using a friendlier tone of voice (i.e., no differences in prosody). To rule out differences in prosody, audio clips were lowpass filtered following established methods for examining natural language33 and evaluated by an independent sample of adult participants (N = 1122). See Supplementary Methods I for details of equivalence tests (Emory University IRB reviewed and approved the study before data collection (protocol: STUDY00001942) and all participants provided informed consent upon entering the study).

Overview of analyses

All means and standard deviations are raw and unadjusted. All analyses were conducted with a conservative, Bayesian, machine-learning method called Bayesian Causal Forest (BCF). BCF has been found, in multiple open competitions and simulation studies, to identify average treatment effects (ATEs) with minimal bias, while also detecting true sources of treatment effect heterogeneity, if they are present, while not lending much credence to noise34. For a more detailed discussion of the BCF statistical analysis approach employed here, please see the Supplementary Methods A. Average treatment effects and posterior probabilities were calculated from a BCF model fit34,35,36 that included covariates measured prior to assignment to condition. Inferences focused on estimation and uncertainty, following best practice recommendations37. Importantly, BCF are non-parametric and therefore make no assumptions of normality or equal variances. All corresponding two-tailed null hypothesis tests for results reported in the main text were P < .05 (see the SI). We implemented all statistical analyses with R (Version 4.4.0)38.

Manipulation check

To measure transparency, community member participants answered survey questions about the interaction immediately after it ended (Fig. 1B). At the end of the survey, after completing all pre-registered and exploratory dependent measures, they rated the officer’s transparency (three items, e.g., “The officer I talked to stated their intentions for talking to me clearly”). As expected, this analysis showed that community members rated the officer as more transparent in the transparency condition (M = 5.64, SD = 1.22) relative to the control condition (M = 4.41, SD = 1.62), average treatment effect (ATE) = .81 SD [posterior distribution 10th %ile = 0.502, 90th %ile = 1.125], posterior probability that the (ATE > 0) > .99 (Fig. 1C). Note that officers chose to implement this in idiosyncratic ways due to the same discretion they would have outside of the field experiment (see Table 3). Nevertheless, officers’ introductory statements in the treatment condition were perceived as more transparent, compared to the control condition.

Pre-registered outcomes

The primary pre-registered outcome was community members’ perceived threat from law enforcement (3 items, e.g., “The police officer did not trust you,” “The officer just wanted to make friendly conversation” (reverse-scored)). Community members reported feeling less threatened in the transparency condition (M = 2.93, SD = 1.46) relative to the control condition (M = 3.41, SD = 1.43), ATE = −.23 SD [−0.481, −0.010], pr(ATE < 0) = .92.

The secondary pre-registered outcome was trust in the officer’s benevolent intentions (2 items, “In the future, how likely is it that this police officer would go out of their way to help you,” “In the future, how likely is it that this police officer would care about you and your welfare,” 1 = Very unlikely, 7 = Very likely). As predicted, community members reported greater trust in the transparency condition (M = 5.66, SD = 1.15) relative to the control condition (M = 5.30, SD = 1.29), ATE = 0.19 [0.000, 0.401], pr(ATE > 0) = .90 (Fig. 1B).

Language and emotion during the interaction

How did transparency affect the unfolding of the interactions over time? To answer this, a principled exploratory analysis was conducted. This involved a) statistical and idiographic analysis of the language in the transcripts, and b) use of conservative, Bayesian models that reduce false-positive results.

First, natural language processing algorithms39 were applied to the community members’ conversation transcripts. A statistical analysis of all of the conversation transcripts and reflections was conducted, utilizing the popular and well-validated Linguistic Inquiry & Word Count (LIWC-22) software39, which identifies linguistic features of transcripts of which most people are not conscious. Transcripts from the transparency condition showed that the community members used more authentic language by the end of the interaction (i.e., the final third, in terms of each transcript’s word count), ATE = .52 SD [0.277, 0.779], pr(ATE > 0) = .99. Authentic language refers to language in which people reveal themselves in a genuine or honest way, not censoring or filtering. This difference is potentially meaningful because it reveals that participants were using the type of language that tends to form the foundation of positive rapport that makes people feel unthreatened and open to trust. An exploratory analysis of word count also found that community members talked more with officers in the transparency condition, ATE = 210 words [115, 317], pr(ATE > 0) = .99, consistent with the notion that transparency may have helped officers establish rapport.

On the post-experimental survey, participants reflected on thoughts and feelings from the end of the interaction. Exploratory analyses revealed that in the transparency condition civilians’ text included less causal language, ATE = −0.27 SD [−0.506, −0.042], pr(ATE < 0) = .95, suggesting transparency reduced participants’ puzzlement. The natural language analysis also found somewhat more positive emotion words in community members’ written reflections, ATE = .16 SD [−0.059, 0.412], pr(ATE > 0) = .80. Finally, participants reported on the survey which emotions they felt at the end of the interaction. Participants in the transparency (vs. control) condition were less than half as likely to report threatened emotions (afraid, nervous, upset, alert, hostile, ashamed; Raw data Control = 39%; Transparency = 19%), ATE = −0.35 [−0.616, −0.081], pr(ATE < 0) = .95.

These statistical patterns were generally consistent with an idiographic analysis of participants who were identified as statistical outliers on the two pre-registered outcomes of threat and trust40. Idiographic analyses in Fig. 2, Panels A-B, show how different the conversations were in the absence versus presence of a transparency statement. On the top (Panel A), the civilian and officer never established a rapport. Instead, we see terse answers. The civilian is guarded and self-conscious. This interpretation is consistent with their reflections after the interaction. The participant reported being puzzled about why the officer was approaching them and concerned by the threatening prospect that they were being investigated for a crime.

Idiographic analysis of transcripts from police-community interactions (left) and post-interaction reflections (right) for participants in (A) the control condition and (B) transparency condition. Note: Phrases are highlighted to illustrate examples of differences in natural language scored via the LIWC-22 algorithm that were meaningfully different across conditions in statistical analyses of all participants’ data (see the main text). Designed by Freepik, http://www.freepik.com/.

At the bottom of Fig. 2 (Panel B), the interaction in the transparency condition is quite different. This conversation ends with a spontaneous back-and-forth, almost resembling new friends who are at ease with one another. In fact, the civilian invites the officer to have future interactions with them at their place of work. When the civilian reflected on this interaction, they admitted that although they were apprehensive at the very start, by the end they felt “comfortable and like we were friends.” Overall, these transcripts matched the trends we saw in our qualitative research (Table 1).

Stress physiology

We next explored whether the colder and more avoidant response from civilians in the control condition and the more active, warm, engaged response of the transparency condition could be detected through an analysis of sympathetic nervous system (SNS) responses. We conducted an exploratory analysis of skin conductance levels (SCL), obtained from electrodermal activity (EDA) sensors embedded in a wrist-worn ambulatory device. These sensors captured in vivo, temporal dynamics of the stress responses during community members’ interactions with police officers. Higher SCLs have sometimes been viewed as evidence of negative stress, but in the present case they were likely to be positive signs of arousal and active engagement in the conversation. This expectation was derived from the Biopsychosocial (BPS) model of challenge and threat41,42,43 coupled with recent research indicating that civilians spontaneously associate encounters with law enforcement as a threat20, and our own study showing the same (see Supplementary Methods F). To validate the ambulatory EDA data processing algorithms and interpretations, we conducted a pilot laboratory study (N = 100) that administered a controlled stressor (the Trier Social Stress Test) and collected data from the same wearable EDA sensors as in the field study, along with gold-standard psychophysiological measures of challenge and threat (e.g., Total Peripheral Resistance; details reported in SI Fig. S2A-B)44,45. Based on the results of our prior validation study, we expected the following trends to emerge when participants received the transparency statement: (a) initial effects on higher SCL at the outset of the interaction relative to controls, and (b) quicker recovery to homeostasis over time, resulting in reversed treatment effects relative to controls during the recovery epoch.

Indeed, we found a positive effect of transparency statements on SCL during the initial ten seconds of the interaction, CATE = 0.15 SD [0.045, 0.258], pr(ATE > 0) = .97. See Fig. 3A and B. This shows greater arousal, and it is generally consistent with openness to a new, positive relationship with the police officer. Next, we found a stronger decline over time in SCL in the transparency condition, consistent with less arousal. By the end of the interaction, the treatment effect had reversed, yielding a difference in CATEs for the first 10 seconds vs. the recovery period of .22 SD [0.109, 0.341], pr(CATE for first 10 seconds > CATE for recovery) > .99. In summary, the EDA data in Fig. 3A and B were consistent with greater initial arousal, and less arousal during recovery, in the transparency condition compared to the control condition.

Differences in the temporal dynamics of the police interaction across experimental conditions depicted as (A) overall skin conductance level (SCL) and (B) conditional average treatment effects on SCL (N = 177). Note: SCL Skin conductance level. Results in panels A and B were generated by a multilevel random intercept model that used Bayesian Additive Regression Trees (BART), a machine-learning algorithm with conservative prior distributions, to estimate the non-parametric effect of time on SCL and on the treatment effects. Panel A presents loess-smoothed means of the posterior distribution of SCL reactivity estimated by the BART model. In panel B, dark lines correspond to the median of the posterior distribution of effects, boxes correspond to the inter-quartile range, and whiskers correspond to the 2.5th to 97.5th intervals. SCL was indexed by the average second derivative of EDA with respect to time during each 10-second window. A positive second derivative signals more rapid increases in EDA, which signals an impending peak and thus an SCL event, while a negative second derivative signals that an SCL event is ending and therefore the participant’s SNS arousal was in the process of recovering to homeostasis. The second derivative was used to follow recommendations from papers validating SCL data which have argued43,44 that a better way to use information from a continuously monitored SCL is to calculate rates of change in slopes rather than discretely coding SCL events, which discards observations, especially when there is a low sampling rate, as in the present case. In our separate pilot study that validated our SCL facets, the second derivative metric was three times more effective at distinguishing challenge and threat levels to a lab stressor than a frequently-used skin conductance response event coding algorithm (see the SI).

Replication and moderation by racial/ethnic demographics

Experiment 2 (N = 969) was a pre-registered online study that replicated Experiment 1’s findings using a brief video-recorded introduction from a uniformed police officer stopping to talk with a community member in a park. The sample was constructed to resemble the U.S. population’s marginal distributions of age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Because a key goal of community (vs. proactive) policing is to reduce inequality in trust in police, this study tested whether group memberships moderated the effects of transparency. On the one hand, people of color and those from lower-SES contexts tend to have more negative attitudes towards law enforcement at baseline46, potentially reducing the efficacy of a simple transparency statement11. On the other hand, over-policed racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic groups might benefit the most from transparency because it addresses the attributional ambiguity that comes from being targeted by stereotypes22,23. The present study had the opportunity to assess these two competing hypotheses using a sample with greater statistical power than Experiment 1. A secondary goal of Experiment 2 was to replicate our primary results using a more comprehensive, 10-item measure of threat.

We collaborated with a White, male police officer to co-create an authentic implementation of the transparency statement in real-world settings for this video manipulation. In both conditions, we used the same White, male focal officer for two reasons. First, a White, male officer is the prototypical police officer in the United States. From the most recent statistics in 2020, the population of police officers in the US comprised 86% men and 66% non-Hispanic White officers47. Second, White, male police officers are likely perceived as most threatening compared to all other racial and gender groups because they have been the most likely to use force against community members48. In the control video, the police officer said “Hey there, I’m [Officer Name], I’m just out here saying hi and seeing how things are going” (cf. Table 3). In the transparency condition, the officer said, “I’m out here on foot patrol, just trying to get to know my beat and my community.” The specific wording of this transparency statement was developed to feel authentic to the officer, resulting in greater experimental realism49, but it nevertheless kept to the core of a transparency statement, which was to explain the reasons for their behaviors. Importantly, there were no differences in perceived officer prosody when following the same methods used in Experiment 133 (see Supplementary Methods J for details).

Replicating Experiment 1, the transparency statement reduced threat on the full 10-item measure: ATE = −0.23 [−0.391, −0.088], pr(ATE < 0) = .97. Results were the same for the 3-item subset (matching Experiment 1): ATE = −0.32 [−0.533, −0.131], pr(ATE < 0) = .98. The transparency statement also increased trust, ATE = 0.10 [0.000, 0.211], pr(ATE > 0) = .90, and behavioral intentions to initiate rapport with officers in the future (focal officer: ATE = 0.23 [0.046, 0.435], pr(ATE > 0) = .94; other officers from the same department: ATE = 0.14 [0.022, 0.259], pr(ATE > 0) = .94). Thus, the transparency effects replicated in this national, diverse sample.

Interestingly, we found no consistent evidence of moderation by demographic group (i.e., age, gender, race/ethnicity, native U.S. status, education, income, conservatism, baseline attitudes towards police, and history of prior police contact; see Table S8 in the supplemental). In the few cases where there was evidence of moderation, the transparency statement was more effective for those who would be expected to have more negative attitudes towards the police initially (e.g., members of racial minority groups). This provides initial exploratory evidence that transparency statements may have the potential to reflect a scalable intervention with the potential to benefit individuals from historically over-policed communities.

Controlled online experiments

What are the elements of a strong transparency statement, when do they work, and when do they not work? To answer these questions, we conducted five pre-registered, randomized, controlled experiments using online samples of adult volunteers who anticipated an interaction with an authority figure. In these experiments, we manipulated aspects of the introductory statements of the authority figures and examined effects on the focal, pre-registered threat measure from Experiments 1 and 2. Extended details on the samples and study procedures are presented in Supplementary Methods K. We note that across the seven experiments’ main effects the results were consistent across methodologies (e.g., field vs. vignette) and era (i.e., data collected prior to the murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor in 2020 vs. after May 2020).

In these five experiments, we moved to an online vignette-based design. We did so because our primary aim was to turn on and off certain elements of transparency statement using controlled experiments. After ensuring that the main effect of transparency statements translated to a vignette-based design, we varied aspects of the transparency situation to advance an understanding of mechanism.

An initial vignette study (Experiment 3, N = 609) replicated Experiment 1-2’s findings using an anticipated interaction with a police officer stopping to talk with a community member outside of a grocery store. Participants in the control condition imagined that the police officer started a conversation by saying “Hi, how are you doing?” In the transparency condition, they anticipated interacting with an officer who explained that they were “just trying to get to know the community better.” As with the live interaction and video study, the transparency statement reduced threat in this anticipated situation, ATE = −0.44 SD [−0.762, −0.077], pr(ATE < 0) = .95. In the four experiments that follow, the same effect was replicated each time (see the Supplementary Methods K).

We next asked: Do officers’ intentions need to explicitly convey benevolence to have a beneficial effect? In Experiment 4 (N = 382), we used a three-condition design to compare the transparency statement to an introduction that was transparent about the officer’s intentions, but the intentions conveyed a potentially harmful intent (i.e., the officer is “trying to find a suspect in the area”), and the control condition. We suspected that the introductory statement—though transparent—would not be as effective because it does not disabuse the participant of the significant concern that they will be accused of a crime. We found that the introduction that conveyed potentially harmful intent was highly different from the replicated reduction in threat from the transparency statement, Difference in ATEs = −0.43 SD [−0.688, −0.130], pr(ATEambiguous> ATEtransparency) = .95. Furthermore, the introduction that conveyed potentially harmful intent also substantially increased threat compared to a control condition, ATE = 0.38 SD [0.097, 0.623], pr(ATE > 0) = .94, consistent with qualitative accounts of the investigatory stop in the proactive policing model. Thus, only transparency statements that explicitly convey benevolent intent reduce threat.

What if an introductory statement communicated benevolent intent, but did so in a way that still left open the possibility that the civilian could perceive it to be an investigatory stop? In Experiment 5 (N = 450), we used a three-condition design to compare an ambiguously positive introduction (i.e., the officer “just wanted to stop and say hi and see how you are doing”) to the transparency statement and to a control condition. The ambiguously positive introduction yielded similar levels of threat to the control condition, ATE = 0.12 SD [−0.064, 0.337], pr(ATE < 0) = .18, and the magnitude of difference between these two conditions was much smaller than the threat reduction effect obtained from the transparency statement, Difference in ATEs = −0.39 SD [−0.543, −0.232], pr(ATEambiguous>ATEtransparency) > .99. A follow-up analysis suggested that this was because participants thought the officer in the ambiguously positive condition was concealing their true intentions (see Table S15 in the SI). Thus, transparency statements seem to reduce threat not simply because they are friendly, positive, or respectful, but because they more clearly take off the table the possibility that individuals are going to be accused of a crime by law enforcement.

Two final experiments used a different approach to test our assumption that transparency statements are beneficial primarily because they make it clear to the community member that they are not under threat of arrest or bodily harm while they are being questioned. We did this by varying the social role of the interaction partner. In Experiment 6 (N = 349), a four-cell study (2 \(\times \,\)2 design), as a contrast, participants anticipated interacting with someone who had no authority to arrest or harm them: a grocery store worker. In the interaction with the grocery store worker, there was no evidence of a reduction in threat in the transparency condition relative to the control condition, ATE = −0.03 SD [−0.276, 0.202], pr(ATE < 0) = .58, and magnitude of difference between the transparency and control introduction for the grocery store worker was much smaller than an effect obtained from an anticipated police officer interaction, difference in ATEs = −0.60 SD [−0.950, −0.254], pr(ATEgrocery < ATEpolice) = .99.

In Experiment 7 (N = 451), the final four-cell study, participants anticipated interacting with someone who technically did have authority to arrest or harm the participant, but who was very unlikely to do so because it is not common practice in their role: a park ranger. When participants anticipated interacting with a park ranger, the transparency statement did reduce threat relative to the control condition, ATE = −0.53 SD [−0.754, −0.311], pr(ATE < 0) > .99, but this transparency effect was approximately half the size of the effect obtained when participants anticipated interacting with a police officer, difference in ATEs = −0.69 SD [−1.008, −0.372], pr(ATEpark ranger < ATEpolice) > .99.

In summary, transparency statements work best—and are most needed—when they shift the default construal of an interaction, from one that could end in harm or arrest, to one that could end in a positive relationship with a powerful authority figure. We note that the goal of these online studies was to establish internal validity with respect to transparency statements and their mechanisms. We do not make claims of generalizability based on these samples.

Discussion

This research identified a simple and relatively costless method for making community-police interactions less threatening: a transparency statement. In doing so it highlighted the under-appreciated role of timing in conversations between institutional authorities (i.e., law enforcement officers) and civilians. Notably, our observations and interviews19 found that traditional patrol officers typically made transparency statements only after trust had been compromised. Consistent with this qualitative observation, our study showed that absent a transparency statement at the start of the conversation, the officers’ questions contributed to a sense of threat. Potentially supporting this threat, in these interactions community members also displayed an avoidant conversational style (i.e., less authentic, terser) and physiological profile (lower initial arousal). When officers made transparency statements in the first two sentences of the conversation, however, it changed the tenor of the ensuing interaction. For example, an exploratory analysis revealed that twice as many community members reported feeling inspired by the end of the interaction when officers made a transparency statement (28%) than when they did not (14%; see SI and Fig. 1C). There was evidence consistent with this shift in transcripts, self-reports, and stress physiology.

The present studies raise the intriguing possibility that community policing, in general, might be made more reliably effective if officers could be trained to incorporate transparency statements into their routines. Indeed, in Experiment 1, we individually instructed seven officers in less than five minutes per officer—instruction that might be done efficiently with entire departments. The present study lays the foundation for larger, longitudinal evaluations that assess downstream consequences of transparency trainings on outcomes such as wrongful arrests or official excessive use of force complaints, along with greater trust in the benevolence of police officers, more information sharing, more solved cases, and safer communities.

Our studies examined the effect of a transparency statement (relative to a business-as-usual control condition) on civilians’ threat and trust in a nonenforcement interaction with law enforcement. However, these studies are not without their limitations and offer promising directions for future research.

First, our work was deeply grounded in the U.S. context due to the history of police brutality and low levels of trust in law enforcement in this cultural context11,12,13. While we anticipate that the fundamental concept of transparency statements has the potential to translate across cultural contexts (especially to other cultural contexts where trust in law enforcement is low16), future work should seek to calibrate this intervention to other cultural contexts50 and replicate our findings regarding transparency statements in other cultural contexts beyond the U.S. Similarly, our work was conducted utilizing a variety of distinct U.S. samples (observations in large urban areas, naturalistic field study in large, urban area, and national online samples). However, future work should continue to extend and replicate our findings in different communities to expand the generalizability of the transparency statement intervention.

Second, our work began with a qualitative observation phase which led us to conclude that transparency statements worked best in the field when they came first. These observations inspired our hypotheses and the design of our field experiment, leading us to intervene on first contact. Our observations are further supported by related basic psychophysiological research that documents an immediate civilian threat response upon mere exposure to police (vs. non-police) stimuli18. Furthermore, supplemental analyses of our Study 1 (see Supplementary Methods G) indicate that for the few conversations in the control condition where an officer made a transparency statement later in the interaction, there were no observable benefits relative to those conversations where no transparency statement was made, providing initial exploratory evidence that transparency statements are most beneficial when they come first. Due to our field observations and recent basic psychophysiological research, our theorizing rested on the effect of transparency statements at the outset of the conversation (vs. not). However, future work should systematically examine whether transparency statements issued later in conversations confer any benefits.

Third, our mixed-methods approach yielded consistent findings across both relatively naturalistic settings in the field and controlled, online settings, consistent with meta-analytic reviews of organizational behavior research51. However, of note, not all social science disciplines have such high correlations between field and laboratory settings (e.g., social psychology, r = 0.53). Indeed, many social-psychological effects are contextually sensitive52,53,54. Therefore, future research should seek to understand more deeply the parameters that lead to consistent vs. inconsistent effects in the field and the laboratory.

A key consideration for future research is whether transparency statements could play a role in reducing racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in policing policies5,7,55,56. The results of Experiment 2 suggest that, if anything, people of color57 and those who have a history of contact with police may profit more from greater transparency58. Future experiments, however, should interrogate any potential heterogeneity more systematically, and across multiple levels (individuals and neighborhoods), due to the tight link in the U.S. between individuals’ racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic identities and their neighborhood contexts59.

These findings also have implications for building trust in other organizational relationships with significant power disparities (e.g., border patrol agents, teachers, security guards). We speculate that transparency statements will be especially needed when authority figures can harm those in lower power positions, as is the case for police, principals, teachers and others49. In these settings, transparency statements might assure students of their benevolent intent, and might prevent escalating negative reactions from children to these authority figures.

Finally, we note that criminal justice reform efforts often seek to change officer behavior via broad and abstract cultural changes8,60. Police departments often resist change, however2. Officers remain skeptical of the effectiveness of community policing, or any other reform, as they retain traditionally proactive and aggressive tactics. Our results suggest that reforms that are nearer to officer behaviors—such as interactions with community members—represent an alternative but nevertheless viable pathway to police reform that might be both effective and scalable.

Methods

Pilot study: community members’ emotions in response to Police

We corroborated the claim that anxiety and threat reflect the dominant emotional responses to interactions with law enforcement in a separate supplemental study in which N = 251 participants described the last encounter they had had with law enforcement, as well as their feelings during the beginning, middle, and end of the interaction. Fully 75% of participants described feeling anxious at the outset of the interaction (vs. 11% who described a positive emotion, and 11% who described another negative emotion). See Supplementary Methods D for further details of this study.

Phase 1: hypothesis generation via qualitative field observations

In the first phase, we used qualitative methods to understand how community policing efforts might be improved and to generate the hypotheses about transparency statements that we tested in Phases 2–3. Note that we cannot make strong claims from our qualitative methods about fully capturing the dynamics of transparency statements in community policing units. Instead, here we are simply presenting the systematic approach we took that enabled us to capture ecologically valid police-community interactions in the field, as recommended by criminology researchers61. These field observations ultimately enabled us to develop a falsifiable hypothesis about the potential positive impact of transparency statements in community policing.

Research settings

There were two concurrent strands to the field observations we conducted. We began, first, as part of a larger team of researchers observing a new community-oriented policing unit that was developed to address the community’s problems by quickly building relationships with community members. In parallel, we observed traditional patrol officers in a different department in the same metropolitan area. We focus here on the most relevant findings about the distinct dyadic interaction tactics law enforcement officers used and their relative effectiveness regarding building trust and rapport with their communities, because these were the observations that led us to develop the present hypotheses. Many other observations were conducted regarding the governance and decision-making of the two police departments, but these data are less relevant to the present transparency hypotheses. See Supplementary Methods B for additional background information on community policing.

Community policing unit

The first team we observed was a police department in a large, urban city, and the specific unit was located in a district that included portions or entireties of eight neighborhoods with a mixed population of diverse racial and socioeconomic groups (total population range = 14,318 – 93,727; 6–62% White; 15–83% Hispanic/Latinx; 2–78% Black/African American; 1–6% Asian/Asian American; 1–3% Other/Multiple Races; Median Age = 32.2 – 41.9 years old; 13–57% population 25+ with a 4-year college degree or greater; 61–94% Native US; 3.5–12.6% unemployed; median household income = $33,515 – $82,908). For example, one beat we observed was 62% White residents with a median income of $72,272. Another beat we observed, in contrast, was only 6% White and 78% Black/African American with a median income of $33,515. This city had a population of more than 2 million residents, and the police department had more than 10,000 officers at the time of our data collection. The unit we focused on was testing a pilot program that reorganized the duties of their officers. While officers traditionally go from call-to-call according to their radios, this unit was given discretion over how they used their time, with the goal to spend it oriented towards building relationships with the community in their assigned area and coordinating resources that their communities needed. Officers in this unit were recruited from the entire citywide department by the lieutenant in charge of the unit, ostensibly selected on traits that would facilitate relationship-building in communities (e.g., genuine interest in relationship-building, prior history of attempting to build relationships within the constraints of a patrol officer’s role). This phase provided us with an understanding of how officers who were ostensibly skilled at building relationships with community members attempted to quickly build trust with civilians. Examples of this process appear in Table 1, right panel, Experiments 1–2.

Traditional patrol unit

In parallel, we partnered with another police department in the same metropolitan area to observe more traditional interactions of police whose responsibilities are dictated by radio calls and less focused on developing skills related to connecting with their communities. The employees we observed were patrol officers from a different police department in a moderately-sized, suburban city that was nearby to the city where the community policing unit was located. This city was also relatively racially and socioeconomically diverse (58% White; 12% Hispanic/Latinx; 17% Black/African American; 9% Asian/Asian American; 7% Other/Multiple Races; Median Age = 36.2 years old; 67% population 25+ with a 4-year college degree or greater; 82% Native US; 12% in poverty; median household income = $82,335). This city had a population of approximately 75,000 residents, and the police department had approximately 150 officers at the time of our data collection. After discussions with department leadership, we began a four-week long period of four-hour ride-alongs approximately three to four times per week. Per their supervisors’ instruction, these officers engaged with members of their community as they naturally would if we were not observing them. We observed these interactions and took observational notes on each interaction we observed, and we also obtained direct reflections from both officers and the community members with whom they interacted. We obtained both structured and unstructured reflections from officers after the interaction with the community member ended. First, officers reflected alone via structured question prompts (e.g., “do you think the civilian understood your intentions for talking with them?”; “how connected to the ‘real you’ were you in the interaction?”). Then, we discussed officers’ experiences utilizing unstructured questions. Simultaneously, while the officer left the area to reflect alone, we approached the community members they talked to for an optional, consented debriefing discussion of their interaction utilizing a mix of structured and unstructured questions. These participants provided verbal informed consent. This phase provided us with an understanding of how officers who were not trained in community-based policing attempted to quickly build trust with civilians. An example of this process appears in Table 1, left panel, Ex 2.

Participants

Participants for both phases of the qualitative field observations were the police officers in the two departments we observed (70% Male; 47% White; 30% Hispanic/Latinx; 20% Black/African American; 3% Asian/Asian American; approximate age range: 20–60 years old). In total, more than 35 police were observed across three years, which included interviews, ride-alongs, observed unit meetings, and field observations of community events, resulting in more than 500 hours of data observations. In the community policing unit, we observed 17 officers, four sergeants, one lieutenant, and one commander. Throughout the three years of our observation, more than five officers left the unit due to injuries or to pursue other opportunities in the department. In the traditional patrol unit, we observed 18 patrol officers and approximately 148 civilian interactions. Northwestern University Institutional Review Board (IRB) reviewed and approved this qualitative observation phase prior to data collection (protocol: STU00207172). Observations of interactions were conducted in public settings; therefore, informed consent was not required.

Data and qualitative analysis

Data from both phases come largely from field observations of ride-alongs with the police participants. For the ride-alongs, police were asked to act as they naturally would while we observed from a distance. Field observations of community events, biweekly debriefing meetings, and hour-long interviews were only collected from the community policing unit. Biweekly department meetings in this phase typically consisted of strategic discussions about how to approach community problems together in a roundtable with the whole unit. Interviews occurred in four rounds and consisted primarily of officer views of their role and their community while in the pilot program. Interviews occurred at the recruiting, beginning, middle, and end stages of the officers’ involvement in the pilot program. As mentioned, for the traditional patrol unit, observations of the ride-alongs were accompanied by both officers’ structured and unstructured reflections alone and with the researcher(s) accompanying them on the ride-along. For all field notes, shorthand notes were recorded in small notebooks or on smartphones and expanded after the conclusion of the observation, as soon as possible. Recorded conversations were transcribed by a professional transcription service.

Field notes and interview transcripts were analyzed by the two lead researchers by discussing the day’s data collection immediately or soon after it finished, and writing informal, conceptual, theoretical memos to summarize the emerging themes. Transcripts and notes that were flagged as indicative of key themes were then analyzed line-by-line to understand recurring patterns and to check assumptions against the data. Once the key themes were identified and refined (presented in Table 1), then exemplary quotations were selected to illustrate those themes to readers. These quotations were then vetted with a third researcher, to reach agreement on the fit between the data and our interpretations of the data. Following best practices for qualitative, inductive research, we continued to collect qualitative observation data until thematic saturation was reached62. After reducing the qualitative data to the key themes and focal examples (Table 1), we used these insights to design the randomized experiments and test the hypotheses directly. Additional thematic examples appear in the SI.

Phase 2: hypothesis testing in naturalistic experiment in the field study 1

Participants

The study was pre-registered on OSF on June 17, 2021 (https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/tz6se). We made one deviation from our pre-registration: in our pre-registration we indicated we would exclude conversations longer than 5 minutes. However, in practice this was a flawed criterion because the treatment was only the officer’s introductory statement, and officers were instructed to carry on conversations naturally with no other intervention. Moreover, this exclusion would result in removing 60 valid and complete observations, unnecessarily limiting our sample size and statistical power. Therefore, we instead retained all observations regardless of conversation length. We planned to collect data from a total of 200 participants, which afforded the ability to detect an effect of 0.40 SD at 80 percent power using conventional null hypothesis rejection analyses. Following the pre-registered stopping rule, data collection was terminated on the first day that we met or exceeded our sample size. No data were examined, and no hypotheses were tested prior to stopping data collection.

We ultimately collected data from 239 U.S. residents from a sample of community members in a large urban city from streets nearby, Craig’s list ads, emails throughout departments to the local university, and word of mouth. We recruited this sample in an attempt to represent the community that the police agency serves. After excluding seven individuals who either opted to have their data deleted after learning the full details of the study (n = 3) or had incomplete data (n = 4), we were left with a final sample of 232 (Mage = 22.07, SD = 5.90; In this and all subsequent studies, participants self-identified their gender and racial/ethnic identity: 54% identified as female, 41% identified as male, 4% identified as non-binary/genderqueer/other; 33% identified as Whites/European Americans, 33% identified as Asian/Asian Americans, 17% identified as Latinx/Hispanic Americans, 9% identified as Black/African Americans, 5% identified as multi-ethnic, 3% identified as biracial; conservatism M = 2.68, SD = 1.35 [scale: 1 = very liberal to 7 = very conservative]). The University of Texas-Austin IRB reviewed and approved the study before data collection (protocol: STUDY00000613) and all participants provided informed consent upon entering the study.

Naturalistic study design

To design a realistic behavioral experiment conducted in a naturalistic field setting63,64 that would accurately capture the effect of transparency statements and also yield results using intrusive behavioral psychophysiological and linguistic measures, we had to carefully consider tradeoffs on criteria necessary for conducting field experiments. See Table 2 for a breakdown of field experiment criteria, whether our study achieved each of these criteria, rationale for why the study did or did not achieve a given criterion, and evidence to support that rationale.

Transparency statement material development

The study design was created with informal police consultants, who were current and retired police officers from three departments. We developed our procedure to realistically reflect what police do in officer-initiated interactions with their communities, while maintaining alignment with our definition of transparency (i.e., clarifying intentions for approaching civilians).

Civilian participants

This study was conducted during June and July of 2021. Civilian (i.e., community member) participants were told that the study was about the natural interactions people had with others. Civilian participants were seated individually at a table around a university building in one of five predetermined locations that were not in-view of each other (e.g., a patio table; a bench). Civilian participants were told that they should do what they would naturally do if they were sitting by themselves outside (e.g., using their cell phones or computers). The research assistant left the participants alone with an iPad and stated that everything would be audio-recorded by the iPad during the experiment. Participants did not know who they would be interacting with but were told to act naturally if (and when) anyone approached them.

To mask the anticipation of a police officer approaching while also allowing for informed consent, participants were told in their consent form that due to the outdoor nature of the research study, they may be approached by a research assistant, unsheltered (i.e., homeless) person, student, police officer, or others in the area. Once the conversation started, the officers never stated that they were a part of the research study.

Police officer partners

The police officer partners (N = 7) for this field experiment were employees of the police department with jurisdiction over the community of recruited civilian participants. That is, actors were not used, and all officers in the study were on-duty employees during their regularly scheduled work shifts, not trained confederates; this decision was made to increase the ecological validity of the experiment.

Prior to conducting this research, the research team met with police department leadership, who approved the partnership. The seven police officers were recruited by the leadership because they were considered by leaders to be representative of the diversity of officers using community policing efforts in this police department. Training of the officers lasted approximately five minutes per officer. The officers overall spent approximately 60 hours on data collection in the role of an experimenter.

Police partners were told to initiate interactions with civilians in one of two ways: either providing a transparency statement (i.e., giving explicit reasons for why they are approaching the participant, at the outset of the interaction) or not (our control condition; i.e., using the ambiguous, direct, and short language that simply asks if they can talk to the civilian participants). Police partners were instructed to keep their conversations short (i.e., to five minutes or less, aiming for 2 minutes), but were otherwise left to their own natural conversation style after the introduction. They did not follow an exact script. Notably transcripts confirmed that 100% of the officers in the transparency condition made a transparency statement, and 0% of the officers in the control condition did so at the outset of the conversation.

For example, in the transparency condition (N = 100), officers initiated interactions in the following ways: e.g., “Hello, I’m just out and about walking around, talking to people in the community. Is it okay if I talk to you for a minute?” “Hey, my name is [Name], and I’m just taking a walk, trying to get to know my community better. You mind if I sit and talk to you for a second?”

In contrast, in the control condition (N = 132), officers initiated interactions in the following ways: e.g., “Hey, can I talk to you for a minute?” “Hey, I’m Officer [Name], can I talk to you for a second?”

Assignment to condition

Leadership in the police department assigned officers to one of several shifts for the experiment. Researchers, blind to the identities or skills of the officers, assigned officers’ shifts to experimental conditions, so that in some shifts officers used transparency statements, and during other shifts they did not. Civilians, in turn, were assigned to different shifts independently of the officers’ condition assignments. The experiment was not randomized. There were an equal number of weekend shifts across conditions. Within experimental conditions, shift was not meaningfully associated with the pre-registered outcomes of threat and trust (Threat: Control group intraclass correlation [ICC] = .04; Transparency group ICC = .02; Trust: Control group ICC = 0; Transparency group ICC = 0). As a result, supplementary, non-pre-registered mixed-effects analyses that clustered standard errors by shift did not produce different results (Threat: b = −0.47, t(225) = −2.45, p = .015, d = −0.326, 95% CI [−0.840, −0.097]; Trust: b = 0.36, t(225) = 2.22, p = .027, d = 0.296, 95% CI [0.046, 0.675]). Furthermore, no participant demographics (i.e., age, gender, race, native U.S. status, education level) differed significantly by condition, t’s ≤ 1.106, p’s ≥ .270, d’s ≤ .144 (see Table S3 in SI) or shift (see Table S4 in SI; see Supplementary Methods G for model assumption tests for these analyses).

Measures

Unless otherwise acknowledged, all measures were on a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree. For all measures, civilian participants read that their individual data would not be shared with the police (i.e., that data collection was confidential). Full lists of the scale items can be found on OSF https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/tz6se and additional information and results can be found in Supplementary Methods G-H. See Supplementary Methods See Table S5 in the SI for correlations among all primary variables. All survey data across all experiments were collected via Qualtrics survey software65.

Measure order

Participants first completed our primary pre-registered dependent measures of threat and trust, exploratory measures of thoughts and feelings during the interaction, and finally, after all dependent measures, completed a manipulation check measure assessing perceived officer transparency (see https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/tz6se for all study materials and the order in which they were completed across all studies presented here).

Manipulation check: perceptions of transparency of intentions

As a manipulation check, we measured civilian participants’ perceived clarity of the police partners’ intentions (i.e., “The officer I talked to stated their intentions for talking to me clearly”; “The officer I talked to stated their intentions for talking to me immediately”; “I knew why the officer was talking to me from start to finish”; α = .757).

Primary measure 1: threat of enforcement

Perceived threat was a primary measure due to its prominence in civilians’ reflections of their interactions with police during Phase 1 (see SI). Civilians’ self-reports of threat were measured using three items that operationalized threat as the expectation of harm in the interaction. Specifically, these questions asked how likely (1 = Very unlikely to 7 = Very likely) it was that the police officer they talked to “just wanted to get to know you,” (reversed) “just wanted to make friendly conversation,” (reversed) or “did not trust you” α = .768. Moreover, a principal components analysis of these three items indicated that all three items loaded highly (loadings ≥ 0.81) onto a single component accounting for 77% of the total variance.

Primary measure 2: trust in benevolent intent

Trust is viewed as the first step towards repairing relationships between law enforcement and civilians in the community policing model16. Civilian participants’ trust was measured using three items adapted from the benevolence subscale of a validated trust scale66, using the same likelihood scale as threat, regarding future interactions with the police officer they were approached by: “This police officer would care about you and your welfare;” “this police officer would go out of their way to help you; this police officer would not do anything to hurt you.” α = .630). When including the third item assessing trust (which showed unexpectedly weak correlations with the other two items), we found that civilians in the transparency condition reported directionally more trust (M = 5.59, SD = 1.12) than those in the control condition but this failed to reach conventional levels of significance (M = 5.30, SD = 1.19), t(229) = −1.96, p = .051, d = −0.256, 95% CI [−0.590, 0.001] (see Supplementary Methods G for model assumption tests for this analysis). In effect, there were no treatment effects on the single item that showed very low reliability and appeared to confuse participants due to its reverse wording67, but there was a meaningful effect on the two other items combined.

Natural language analysis

Audio recordings of conversations

Audio was recorded by an iPad device positioned on the table where the civilian participant was seated. Audio began recording when the research assistant set the participant up alone during the pre-interaction waiting period through when the interaction ended, when the research assistant returned to turn the recording device off. All audio recordings were later transcribed and turned into text files by research assistants.

Natural language processing: conversation transcripts

Text analyses of transcripts of the conversations between civilians and officers were divided by speaker role (i.e., officer vs. civilian), condition (i.e., transparency vs. control), and by portion of the conversation (i.e., first, middle, or last third). Transcripts were analyzed with the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC) Software39.

LIWC is one of the most dominant text analysis software in the social sciences and relies on a “word counting” method that both tallies counts of parts of speech like prepositions, adverbs, and pronouns68, and also includes four summary dimensions validated in previous research: Analytic69, Clout70, Authenticity71, and Emotional Tone72. We analyzed the end of the civilian side conversation transcripts and obtained their score on each of these summary dimensions. The Authenticity summary dimension included in LIWC is a composite score validated in prior research and reflects honest, unfiltered, and spontaneous speech71. It is a bottom-up composite measure that was built based on research on deception and language use. The language categories that comprise the authenticity dimension resulted from factor-analyzing texts of truthful vs. deceptive language73. We expected that the transparency statement would increase civilians’ use of authentic language, because the transparency statement puts civilians at ease and enables rapport to be built. We did not anticipate differences on any of the other dimensions, but we analyzed them along all summary dimensions to document the specificity of the effect of transparency statements on authentic language.

Natural language analysis: civilian reflections on the interaction

On the post-interaction survey, participants answered an open-ended question asking about the thoughts (one question) and feelings (a second question) they experienced at the end of the interaction. These reflections were also scored with the LIWC-22 algorithm. Analyses focused on two patterns that emerged from the idiographic analysis. The first is causal language or signaling people’s tendency to ponder the cause of the officer’s interactions (i.e., “I was wondering why he was talking to me”). We expected the transparency statement to reduce causal language in the reflections, because the primary goal of the transparency statement is to answer the question of why the officer is talking to them. The second was positive emotion (e.g., comfortable, happy). We expected the transparency statement to increase positive emotion at the end of the interaction, because the statement should provide the foundation for rapport that could result in a positive back-and-forth dialogue.

Emotion at the end of the interaction

On the post-interaction survey, civilian participants completed the Short Form version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS-SF74), selecting an emotion they felt at the end of the interaction. In the standard PANAS-SF measure, there are several emotion categories that correspond to operationalizations of threat (vs. challenge) appraisal41,42,43. Emotions were coded for threat (1 = alert, afraid, nervous, upset, hostile, or ashamed; 0 = not). In addition, one emotion (inspired) was explored, due to its alignment with community policing’s goals.

Skin conductance levels (SCL)

To distinguish between patterns of arousal in the transparency (vs. control) condition, skin conductance levels (SCL), were obtained from electrodermal activity (EDA) sensors embedded in a wrist-worn ambulatory device: the Empatica E4. The Empatica E4 wristband measures physiological responses to stress simultaneously via two sensors placed on the bottom of the wrist75,76. The E4 sensors have a resolution of 1 digit ~900 picoSiemens, a range from 0.01microSiemens to 100 microSiemens and they apply alternating current (8 Hz frequency) with a maximum peak to peak value of 100microAmps (at 100microSiemens).

EDA assesses changes in the amount of conductance of the skin (i.e., SCL) due to sweat produced by eccrine glands; increased SCLs correspond to increased sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activation innervated by acetylcholine44.

We instructed participants to push a button our ambulatory devices whenever someone started to talk to the participant. Pushing this button recorded a timestamp in the ambulatory device data. Because of this participant-led action, some participants forgot to push the button to indicate the interaction started. This is a potential limitation because it caused missing psychophysiological data (the SCL subsample was N = 177). However, this missing data was unavoidable to retain the realism of the unexpected officer-initiated interactions.

SCL theoretical expectations

According to the BPS model, SNS arousal during a stressful interaction can follow one of two patterns: a more positive, challenge-type response or a more negative, threat-type response. A challenge-type response corresponds to approach motivation and evokes an initial orienting response with the onset of the stressor (e.g., the approach of the officer20), which involves a rapid increase in SNS activity41,42,43. But a challenge-type response would involve a rapid return to homeostasis as the interaction is not experienced as a potential threat42,43,44. In contrast, more negative, avoidance-oriented, threat-type responses often involve blunted initial SNS reactivity, as individuals seek to avoid potentially harmful threats (see Fig. S2A in SI). When individuals cannot escape the stressor, though, those experiencing threat-type responses remain suspicious, vigilant, and alert to impending harm, thus leading their SNS activation to increase over time42,43,44.

As shown in the SI, we validated these expectations with respect to the specific SCL facets extracted from the ambulatory EDA data by using a pilot laboratory study (N = 100) that involved an acutely stressful interaction (the Trier Social Stress Test; TSST77) and gold-standard measures of challenge and threat-type responses (Total Peripheral Resistance, TPR44. In the pilot study shown in Fig. S2A-B in the SI, participants showing challenge-type responses (low TPR) showed an initial increase in SCL at the start of the TSST, as expected, and a sharper decline during recovery, compared to those with threat-type responses (high TPR).

EDA processing