Abstract

The photovoltaic performance of Cu2ZnSn(S,Se)4 is limited by open-circuit voltage losses (ΔVOC) in the radiative (ΔVOCRad) and non-radiative (ΔVOCNrad) limits, due to sub-bandgap absorption and deep defects, respectively. Recently, several devices with power conversion efficiencies approaching 15% have been reported, prompting renewed interest in the possibility that the key performance-limiting factors have been addressed. In this work, we analyze the sources of ΔVOC in these devices and offer directions for future research. We find that ΔVOCRad, arising from bandgap fluctuations and Urbach tails, has been significantly suppressed, with values comparable to those of commercial Cu(In,Ga)(S,Se)2 solar cells. However, the recombination parameter J0, which is more directly related to ΔVOCNrad, shows only modest improvement and must be reduced by four to six orders of magnitude to compete with Cu(In,Ga)(S,Se)2. To approach the theoretical efficiency limit, future work should focus on more directly addressing deep defects and ΔVOCNrad.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thin-film photovoltaics (PV) offer opportunities to target emerging markets such as building-integrated PV, flexible PV, indoor PV, and tandem PV, complementing their use alongside the dominant silicon-based solar cell technologies1,2,3,4. Thin-film PV based on CdTe and Cu(In,Ga)(S,Se)2 (CIGS) is already commercialized and currently accounts for approximately 5% of the market share5. This share is expected to grow as thin-film PV establishes itself in the emerging markets mentioned above. However, the potential of CdTe and CIGS for continued advancement and large-scale deployment is primarily constrained by the limited availability of tellurium and indium6. Although emerging technologies such as organic photovoltaics and hybrid organic–inorganic perovskite photovoltaics have demonstrated high efficiencies at the laboratory scale, their widespread adoption is hindered by inherent stability challenges7,8. In this context, inorganic kesterite Cu2ZnSn(S,Se)4 (CZTSSe), which is structurally and optoelectronically similar to CIGS, offers a promising material system for thin-film solar cells9.

The structure of CZTSSe can be derived from that of CIGS through cation cross-substitution—that is, the trivalent In sites in CIGS are substituted with bivalent Zn and tetravalent Sn10. The direct and tunable bandgap, high absorption coefficient, inherent p-type conductivity, and the presence of abundant and non-toxic constituent elements allowed CZTSSe to adopt the thin-film PV device structure already optimized for CIGS11. Rapid advances in processing and absorber quality optimization culminated in a reported power conversion efficiency (PCE) of 12.6% by the International Business Machines Corporation (IBM) in 201412. However, despite the intense research spurred by this promising result, the record PCE of 12.6% was not matched until 2019, when the Daegu Gyeongbuk Institute of Science and Technology (DGIST) reported a PCE of 12.62%13. Surpassing the 12.6% benchmark took a similarly long time, with a PCE of 13% having been reported only recently, in late 202214. The stagnation in performance improvement of CZTSSe solar cells prompted extensive research into understanding the performance-limiting factors, with losses due to sub-bandgap absorption (exemplified by the large bandgap fluctuations and Urbach energies) and non-radiative recombination due to deep defect states (exemplified by the short minority carrier lifetime) emerging as the two most probable candidates15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29.

In contrast to the protracted development until 2022, recent advancements in the growth and processing of CZTSSe have led to a surge of efficiency records in 2023-24, approaching a PCE over 15%, indicating a new paradigm in the development of CZTSSe solar cells (Table 1)14,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40. Hence, an analysis of recent progress is warranted to help guide future developments toward achieving a commercially relevant PCE of 20%. In particular, conducting a comparative analysis is crucial for distinguishing between the performance-limiting factors that have been mitigated and those that continue to hinder further improvement. In this article, we analyze these recent developments, focusing on reports (including unpublished data) with more than 13% total area PCE and/or more than 14% active area PCE. We find substantial progress in mitigating the performance loss due to sub-bandgap absorption, with values of bandgap fluctuations and Urbach energies for CZTSSe now approaching those observed in CIGS. Nonetheless, non-radiative recombination caused by deep defect states continues to be a key performance bottleneck, as indicated by a recombination parameter J0 that is four to six orders of magnitude higher in CZTSSe compared to CIGS. Our analysis suggests that the optimizations in growth and composition of CZTSSe thin films that have led to the improved PCE must now be supplemented by understanding and suppressing non-radiative recombination at deep defects.

Comparison of normalized photovoltaic metrics

We begin the analysis by comparing the normalized photovoltaic metrics of the recently reported high PCE devices with those of the IBM, DGIST, and CIGS records12,13,41. Note that while a slightly higher efficiency of 23.6% has recently been achieved using silver-alloyed Ag-CIGS, we use the 23.4% efficiency CIGS device for this analysis, as it better represents the intrinsic properties of CIGS42. We normalize the short circuit current (JSC), open-circuit voltage (VOC), fill factor (FF), and power conversion efficiency (PCE) to their Shockley–Queisser (SQ) theoretical limits (JSCSQ, VOCSQ, FFSQ, and PCESQ, respectively) based on the bandgap extracted from the external quantum efficiency (EQE) data. We examine trends in these normalized metrics using the IBM and DGIST records as baselines, with the CIGS record serving as a benchmark goal. The JSC/JSCSQ of kesterite solar cells was already high for the IBM and DGIST cells, with values over 80% of the theoretical maximum (Fig. 1a). This mirrors the CIGS case, where a JSC of 35.5 mA cm−2, already approaching the record of 39.6 mA cm−2, was achieved at a PCE of 14.6%43. Some of the recently reported high PCE devices have improved upon the JSC/JSCSQ of IBM and DGIST cells, with values close to 90%, similar to that of the CIGS record, showing that JSC is not a major limiting factor for CZTSSe solar cells (Fig. 1a). Similarly, the FF/FFSQ has also been improved from less than 80% in the IBM and DGIST cells to more than 85% in some of the recently reported high PCE cells (Fig. 1b). Although further improvements in the FF are desirable, it can be seen in Table 1 that the limitation in FF is not a result of the parasitic resistances (series resistance and shunt conductance). Rather, the reduced FF is a consequence of the low VOC. As has been noted throughout the development cycle of CZTSSe solar cells, a high VOC deficit is the major performance-limiting factor44. This is illustrated in Fig. 1c, that shows VOC/VOCSQ less than 70% even for the recently reported high PCE devices. Although substantial progress has been made to improve the VOC compared to the IBM and DGIST records, the VOC/VOCSQ falls short of both the CIGS record and the theoretical limit. However, it is promising to note that there exists a much stronger correlation between VOC/VOCSQ and PCE/PCESQ (that is, devices with high VOC/VOCSQ also have higher PCE/PCESQ, in contrast to the trend in the JSC/JSCSQ) in the recently reported high PCE devices, suggesting that most of the new records are primarily due to a suppression of VOC loss. We will now take a closer look at the VOC loss in the recently reported high PCE CZTSSe devices.

Analysis of V OC loss

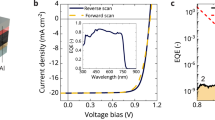

We have recently quantified the VOC loss in the radiative and non-radiative limits (∆VOCRad and ∆VOCNrad, respectively) in emerging chalcogenide thin-film solar cells using external quantum efficiency (EQE) and current-voltage (IV) data. Here, we perform a similar analysis on the recently reported high PCE CZTSSe devices. Since the detailed methodology of this analysis is discussed in our earlier work44, here we only outline the key conceptual background behind the analysis. We define the VOC loss as

The SQ limit assumes a step-like absorption function and no non-radiative recombination losses. Here, ∆VOCRad is the VOC loss due to the lack of a step like absorption function, and ∆VOCNrad is the VOC loss due to non-radiative recombination. We calculate the maximum ∆VOCRad by extracting the bandgap fluctuations (σEg) and Urbach energy (EU) from the EQE spectrum. The σEg is calculated as the standard deviation of a Gaussian fit to the derivative of the EQE around a mean band gap Eg, and EU is calculated from the exponential tail of the EQE below the band gap. It is important to note that reliable extraction of σEg and EU is non-trivial for materials with large values of these metrics, since both σEg and EU set a lower limit on the extraction of the other parameter—that is, σEg sets a lower limit on the value of EU that can be reliably extracted, and vice versa, as discussed in our earlier work44. We extract EU from the exponential tail of the EQE in the sub-bandgap region using

where α is the absorption coefficient and α0 is a constant. Next, we calculate ∆VOCRad due to bandgap fluctuations (∆VOCRad,fluctuations) using

To estimate the ∆VOCRad due to the Urbach tails (∆VOCRad,Urbach), we first create an absorption coefficient spectrum using the Eg and EU extracted from the EQE data. We then estimate the EQE using

where, W is the width of the region from which photogenerated carriers are extracted, which extends over the space charge region and the diffusion length, and α is estimated using the methodology in ref. 45.

Finally, we calculate the ∆VOCRad,Urbach using

and

where ΦBB is the blackbody radiation flux. For J0Rad,Urbach, we perform numerical integration over a wide energy range of 0.5 to 5 eV. The results of this analysis are shown in Table 2. Given the relatively high value of EU for the IBM device, the method above leads to an overestimation of ∆VOCRad,Urbach, as the product EQE × ΦBB diverges at low energy. Hence, in the discussion below, the DGIST device is used for comparative analysis.

VOC loss due to bandgap fluctuations has been substantially reduced in the recently reported high PCE devices as compared to the DGIST device (Fig. 2a). Further, for some of these devices, we see that the ∆VOCRad,fluctuations is smaller than that for record CIGS device. A similar trend emerges in ∆VOCRad,Urbach, where the large losses in the DGIST device have been substantially reduced to approach those of CIGS devices (Fig. 2b). It is promising to note that these metrics corresponding to ∆VOCRad for kesterites are now on par with those for the CIGS device. However, it is also important to note that the total ∆VOC, which is the sum of ∆VOCRad and ∆VOCNrad, is still far below that of CIGS, highlighted by the large difference in VOC/VOCSQ. Further, there also does not seem to be a strong correlation between the PCE/PCESQ and the ∆VOCRad,fluctuations or ∆VOCRad,Urbach of the recently reported high PCE CZTSSe devices. The two observations of (i) similar ∆VOCRad,fluctuations and ∆VOCRad,Urbach in CZTSSe and CIGS, and (ii) smaller VOC/VOCSQ in CZTSSe compared to CIGS suggest that the presence of potential fluctuations and band tails is not currently the major performance-limiting factor in CZTSSe solar cells, as initially suspected46.

a VOC loss due to bandgap fluctuations and b Urbach tails. The VOC loss in the radiative limit due to bandgap fluctuations and Urbach tails for the recently reported high PCE devices is much smaller than those observed in the IBM and DGIST records, with values approaching those for the record CIGS devices. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

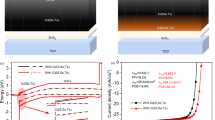

Non-radiative recombination and the recombination parameter J 0

Next, we analyze the major performance-limiting factors by comparing the recombination parameter J047. The total value of J0 extracted from the IV characteristics represents the total recombination current in the device. The different contributions to the total J0 can directly be related to the different recombination channels such as defect-assisted Shockley-Read-Hall recombination, band-to-band recombination, interface or surface recombination, etc47. We extract J0 by fitting the current-voltage characteristics under illumination using the Lambert-W function48. We find that the J0 for the high PCE CZTSSe devices is still four to six orders of magnitude higher than that for CIGS. Further, only modest progress has been made over the IBM and DGIST records. This suggests that the fundamental factors limiting the performance of kesterite solar cells remain largely unaddressed. In addition, the ideality factor, expected to be close to 1 in ideal devices, typically ranges from 1.4 to 2 in CZTSSe solar cells. An ideality factor of 2 typically indicates that recombination is dominated by defect states within the space charge region (SCR)49. Typically, carriers in the SCR are efficiently extracted to external contacts due to the high electric field. However, as has been shown using voltage-dependent time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL) measurements, the decay kinetics in kesterites are insensitive to the applied bias and also to the field in the space-charge region created by the presence of a p-n junction26. This lack of photoluminescence quenching in p-n junctions suggests that recombination in SCR is still a major issue. Further, although we see a trend in ideality factor vs J0, the trendline does not converge towards the J0 for CIGS (Fig. 3b). This is likely because the value of ideality factor is being artificially lowered by other recombination processes. These processes are typically associated with scenarios where recombination is limited by a single type of charge carrier, either electrons or holes, due to trapping in defect states or confinement in potential wells49. Such conditions typically emerge at interfaces and grain boundaries. The trend in ideality factor and J0 suggests that in addition to bulk recombination, interfaces or grain boundaries could also be significant performance-limiting factors. Finally, we note that while suppression of non-radiative recombination caused by band tails could potentially have led to the performance gains in the high PCE devices, the strong correlation observed between J0 and PCE/PCESQ (Fig. 3b) was not observed between ∆VOCRad,fluctuations or ∆VOCRad,Urbach and PCE/PCESQ (Fig. 2), suggesting that the performance gains on top of those obtained from suppressing bandgap fluctuations and Urbach tails have indeed come from suppressing the bulk non-radiative recombination channels. This observation highlights both the promise and the shortcomings of the recent advances that have led to high PCE devices—that is, while the attempts at reducing non-radiative recombination have certainly led to some performance gains, the recombination parameter J0 still remains orders of magnitude higher than what would be required for commercially-relevant PCE.

Defect characteristics

So far, we have discussed the performance of the high PCE devices based on the relevant photovoltaic metrics, without invoking a discussion on the microscopic causes and defect states that lead to performance loss. By deliberately adopting a materials-agnostic approach, we have been able to pinpoint metrics that have improved and those that remain in need of further progress. To guide the next stage of performance improvements, we will now briefly highlight some key material characteristics of CZTSSe that govern its photovoltaic performance.

It is known that the various defects and defect clusters in CZTSSe can cause bandgap fluctuations and non-radiative recombination. In particular, a range of defect clusters and point defects with low formation energies have been identified using first-principles calculations10,24. While the early reports on kesterites focused on CuZn-1 antisite defects and CuZn + ZnCu defect clusters, the shallow nature of these defects limits their contribution to the severely suppressed performance that is observed in CZTSSe50. On the other hand, Sn-related defects, which form both deeper clusters such as 2CuZn + SnZn and point defects such as SnZn2+ with high carrier capture cross sections, are the most likely cause behind the observed performance loss18,25,29,51. Indeed, one of the key recent advancements contributing to improved performance is the shift from Sn2+ to Sn4+ as the tin precursor, which likely suppresses Sn-related surface defects, potentially due to differences in the grain growth mechanisms associated with the two oxidation states52,53. While we have previously provided a comprehensive review of the defect characteristics in CZTSSe44, the present analysis can also be supported by findings from studies reporting high-PCE CZTSSe devices, specifically, the observation of suppressed defect clusters, which in turn mitigate potential fluctuations and band tails. For example, the improved vacancy-enhanced cation ordering that led to 15.4% PCE is expected to suppress the formation of Cu-Zn defect clusters30. The Li-doping and Ag-alloying strategy that led to 14.1% PCE was shown to suppress VCu + ZnCu clusters32. The suppression of elemental inhomogeneity that led to 14.6% PCE was shown to suppress the 2CuZn + SnZn and 2ZnCu + ZnSn clusters, leading to a narrower photoluminescence peak33. Similarly, another report with 14% PCE that achieved the high performance by regulating the nucleation and growth of CZTSSe attributed the improved performance to suppressed ZnCu + VCu, CuZn + SnZn, and ZnSn + 2ZnCu defect clusters that cause potential fluctuations37. Another study with 14.6% PCE showed that multinary alloying led to a smaller difference between the photoluminescence peak and the bandgap, which was attributed to suppressed potential fluctuations35. Another report with 14.5% PCE used Pd(II)/Pd(IV) redox shuttle to passivate grain boundaries and attributed the improved performance to the reduced carrier trapping at potential fluctuations induced by grain boundaries36. While the high PCE papers also report other reasons for the improved performance, such as reduced defects at the CZTSSe/CdS interface14 and in the ZnO buffer layer34, which is indeed supported by the analysis of ideality factor as discussed earlier, our analysis above on trends in the recombination parameter J0 suggests that these performance gains have played a crucial but smaller role as compared to the gains obtained from suppressing the bandgap fluctuation and Urbach tails. This is also highlighted by the observation that the same type of defect character, proposed to be the deep donor SnZn, was observed in devices with widely varying PCE and grown using different methods35. These reports provide robust preliminary results relating defect characteristics to device performance. However, the impact of specific defects on device performance can more reliably be established if the defects in the same absorber material are probed via different approaches such as Raman spectroscopy, capacitance spectroscopy, and photoluminescence. For instance, the assignment of observed performance gains to suppression of specific defects and defect clusters is more reliable if the shifts in the Raman peaks and the activation energies obtained from capacitance spectroscopy and variable-temperature photoluminescence corroborate the theoretically predicted trends.

Future outlook

The performance of photovoltaic materials is closely tied to their intrinsic defect properties. For example, although FeS2 has a favorable band gap, high absorption coefficient, and earth-abundant elements, it has severe VOC loss due to sulfur vacancy defects, limiting the PCE to about 3%54. In contrast, defect-tolerant materials such as halide perovskites and CIGS have led to PCEs of > 20% without the need for defect-free single crystals55,56. The identification of point defects and defect clusters that contribute to performance loss is hence a crucial step, as it informs the strategies to minimize their deleterious effects. The complicated defect landscape of CZTSSe has made it challenging to establish cause-effect relationships between defect types and device performance. However, substantial progress has been made through combined theoretical and experimental studies57. Although a consensus is yet to be reached, the analysis presented above provides a framework to assess the effect of different strategies on ΔVOCRad and ΔVOCNrad. Below, we highlight some strategies that could specifically target ΔVOCNrad (Fig. 4).

Initial device optimizations led to a PCE of 12.6% in 2014. Recent advances, especially in the suppression of VOC loss due to bandgap fluctuations and Urbach tails, combined with suppression of some defects and defect clusters has enabled a PCE of 15%. Future improvements will rely on suppressing non-radiative recombination through synergistic alloying and addressing the recombination at grain boundaries and interfaces.

A majority of the recently reported devices employ some form of isovalent doping and alloying14,31,32,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,58,59. While most of the possible elemental candidates have already been studied, new strategies to incorporate doping/alloying could lead to improved performance. For example, careful design of a gradient bandgap using alloying could provide the benefits of both defect passivation and efficient charge carrier extraction. In addition, while most of the experimental and theoretical studies involving multinary alloying have explored their additive effects, the synergistic effect of alloying two external elements in the same unit cell and its effect on the resultant point defect characteristics could expand the compositional phase space to tune absorber composition for improved performance. This optimization would have to be done in conjunction with identifying the optimum selenization conditions for different compositions while suppressing the formation of secondary phases. This could be achieved through the control of selenization kinetics, as highlighted in some of the recently reported high PCE devices33,37,38,40. While the strategies discussed above would likely address bulk defects, the issue of grain boundary and surface defects could be addressed by identifying more targeted post-deposition treatments, similar to the chloride activation step in CdTe solar cells. The deleterious effect of surface states can also be minimized by optimizing the buffer layer and band alignment. Different optimization strategies may be required for different S/Se ratios, as the band alignment with the buffer layer would depend on the band gap of CZTSSe60,61,62,63. In addition, measuring the band bending due to defects at grain boundaries using techniques such as Kelvin probe force microscopy and quantifying its effect on device performance using drift-diffusion simulations could help identify the most promising approaches for grain boundary passivation64. More advanced techniques, such as cathodoluminescence and electron-beam induced current, can be used to spatially resolve the extent of carrier recombination around grain boundaries65,66.

Eventually, the successful identification of promising methods to improve the photovoltaic performance of CZTSSe will rely on the identification of performance-limiting factors. Commonly used transient techniques, such as time-resolved photoluminescence (TRPL), are not ideal for quantifying non-radiative recombination, as the measured decay times are more strongly influenced by carrier trapping than by non-radiative recombination processes26. This limits the use of transient-based characterization techniques to specific cases where the control sample and the target samples have largely similar but slightly different defect landscapes, such as those observed in individual studies with carefully selected control samples. Indeed, the TRPL carrier lifetimes and PCE of CZTSSe solar cells do not show any correlation26. In contrast, we would like to motivate the research community to adopt characterization techniques that are relevant for comparisons between different research groups while also being directly linked to non-radiative recombination. In this context, the radiative efficiency, measured either via steady-state photoluminescence, electroluminescence, or external quantum efficiency, can be used as a measure of absorber quality44,67,68,69. Radiative efficiency has been shown to directly scale with the PCE for a wide range of photovoltaic technologies70. More importantly, the radiative efficiency scales with ΔVOCNrad, giving a direct means to assess the major performance-limiting factor in CZTSSe solar cells44,71. Since these measurements establish the upper limit of the achievable VOC of the absorber material, the effects of device-level non-idealities, such as interfaces, can then be better understood through the difference between the implied VOC (extracted using optical techniques) and device VOC72. While the measurement of radiative efficiency is currently not common in the CZTSSe literature, the observation of uniform and bright electroluminescence in one of the recently reported high PCE devices can motivate the research community to adopt these techniques30.

Finally, the prospects of commercialization of emerging photovoltaic technologies rely on identifying and exploiting their relative advantages over silicon solar cells44. In this regard, CZTSSe offers (i) opportunities for solution-based production that minimizes capital expenditures, (ii) lower non-module costs due to the possibility of using lightweight and flexible substrates73, and (iii) relative defect-tolerance compared to Si. Policy experts recommend a “means to an end” approach, where emerging technologies such as CZTSSe enter the market via niche applications such as indoor PV, building-integrated PV, etc., and then use this base to enter the broader PV market2,74.

Conclusions

We have performed a comparative analysis of the photovoltaic metrics of the recently reported high PCE CZTSSe devices, focusing on the performance-limiting factors. Of the two major loss factors, (i) bandgap fluctuations and Urbach tails in the radiative limit, and (ii) non-radiative recombination due to deep defects, the former has mostly been addressed with values similar to those for CIGS. However, the recombination parameter J0 and the ideality factor are still substantially higher than those for CIGS. Our analysis presented above, together with insights from the high PCE reports, suggests that the next crucial step for further development of CZTSSe solar cells must focus on deep Sn-related defects and reducing interfacial/grain boundary recombination. Reliable characterization of performance gains using measurement of radiative efficiency will help benchmark the progress made in suppressing non-radiative recombination. Finally, given the seemingly disparate source of losses in the radiative and non-radiative limit, highlighted by the substantial improvement in suppressing the bandgap fluctuations and Urbach tails but only modest suppression of the recombination parameter J0, we note that the strategies that have led to suppressing ΔVOCRad may not be sufficient to suppress ΔVOCNrad, and disruptive strategies must be sought to minimize the overall VOC loss.

Data availability

The data used in this study are available in the Source Data file. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Green, M. A. Photovoltaic technology and visions for the future. Prog. Energy 1, 013001 (2019).

Jean, J., Brown, P. R., Jaffe, R. L., Buonassisi, T. & Bulović, V. Pathways for solar photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 1200 (2015).

Mathews, I., Kantareddy, S. N., Buonassisi, T. & Peters, I. M. Technology and market perspective for indoor photovoltaic cells. Joule 3, 1415 (2019).

Sivaram, V. & Kann, S. Solar power needs a more ambitious cost target. Nat. Energy 1, 1 (2016).

Wilson, G. The multi-TW scale future for photovoltaics. AIP Conf. Proc. 1924, 020003 (2018).

Candelise, C., Winskel, M. & Gross, R. Implications for CdTe and CIGS technologies production costs of indium and tellurium scarcity. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 20, 816 (2012).

Burlingame, Q., Ball, M. & Loo, Y.-L. It’s time to focus on organic solar cell stability. Nat. Energy 5, 947 (2020).

Duan, L. et al. Stability challenges for the commercialization of perovskite–silicon tandem solar cells. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 261 (2023).

Katagiri, H. Cu2ZnSnS4 thin film solar cells. Thin Solid Films 480, 426 (2005).

Chen, S., Gong, X., Walsh, A. & Wei, S.-H. Electronic structure and stability of quaternary chalcogenide semiconductors derived from cation cross-substitution of II-VI and I-III-VI 2 compounds. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 79, 165211 (2009).

Katagiri, H. et al. Development of CZTS-based thin film solar cells. Thin Solid Films 517, 2455 (2009).

Wang, W. et al. Device characteristics of CZTSSe thin-film solar cells with 12.6% efficiency. Adv. Energy Mater. 4, 1301465 (2013).

Son, D.-H. et al. Effect of solid-H 2 S gas reactions on CZTSSe thin film growth and photovoltaic properties of a 12.62% efficiency device. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 25279 (2019).

Gong, Y. et al. Elemental de-mixing-induced epitaxial kesterite/CdS interface enabling 13%-efficiency kesterite solar cells. Nat. Energy 7, 966 (2022).

Rey, G. et al. On the origin of band-tails in kesterite. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 179, 142 (2018).

Larsen, J. K., Scragg, J., Ross, N. & Platzer-Bjorkman, C. Band tails and Cu–Zn disorder in Cu2ZnSnS4 solar cells. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 3, 7520 (2020).

Nishiwaki, M. et al. Tail state formation in solar cell materials: First principles analyses of zincblende, chalcopyrite, kesterite, and hybrid perovskite crystals. Phys. Rev. Mater. 2, 085404 (2018).

Ma, S. et al. Origin of band-tail and deep-donor states in Cu2ZnSnS4 solar cells and their suppression through Sn-poor composition. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 7929, 10 (2019).

Leitao, J. et al. Photoluminescence and electrical study of fluctuating potentials in Cu 2 ZnSnS 4-based thin films. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter Mater. Phys. 84, 024120 (2011).

Scragg, J. J. et al. Cu–Zn disorder and band gap fluctuations in Cu2ZnSn (S, Se) 4: Theoretical and experimental investigations. Phys. Status Solidi 253, 247 (2016).

Walsh, A., Chen, S., Wei, S. H. & Gong, X. G. Kesterite thin-film solar cells: Advances in materials modelling of Cu2ZnSnS4. Adv. Energy Mater. 2, 400 (2012).

Polizzotti, A., Repins, I. L., Noufi, R., Wei, S.-H. & Mitzi, D. B. The state and future prospects of kesterite photovoltaics. Energy Environ. Sci. 6, 3171 (2013).

Yuan, Z. K. et al. Engineering solar cell absorbers by exploring the band alignment and defect disparity: the case of Cu-and Ag-based kesterite compounds. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 6733 (2015).

Chen, S., Walsh, A., Gong, X. G. & Wei, S. H. Classification of lattice defects in the kesterite Cu2ZnSnS4 and Cu2ZnSnSe4 earth-abundant solar cell absorbers. Adv. Mater. 25, 1522 (2013).

Chen, S. Y., Wang, L. W., Walsh, A., Gong, X. G. & Wei, S. H. Abundance of Cu + Sn and 2Cu + Sn defect clusters in kesterite solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 223901 (2012).

Hages, C. J. et al. Identifying the real minority carrier lifetime in nonideal semiconductors: a case study of kesterite materials. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1700167 (2017).

Hadke, S. H. et al. Synergistic effects ofdouble cation substitution in solution-processed CZTS solar cells with over 10% efficiency. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1802540 (2018).

Hadke, S. et al. Effect of Cd on cation redistribution and order-disorder transition in Cu 2 (Zn, Cd) SnS 4. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 26927 (2019).

Hadke, S. et al. Suppressed deep traps and bandgap fluctuations in Cu2CdSnS4 solar cells with≈ 8% efficiency. Adv. Energy Mater. 9, 1902509 (2019).

Wang, J. et al. Vacancy enhanced cation ordering enables >15% efficiency in Kesterite solar cells. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.05974 (2024).

Lou, L. et al. Multi-interface engineering to realize all-solution processed highly efficient Kesterite solar cells. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.06901 (2024).

Gong, Y. et al. Li-doping and Ag-alloying interplay shows the pathway for kesterite solar cells with efficiency over 14%. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2404669 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Suppressing elementinhomogeneity enables 14.9% efficiency CZTSSe solar cells. Adv. Mater. 36, e2400138 (2024).

Lou, L. et al. Crown ether-assisted colloidal ZnO window layer engineering for efficient kesterite (Ag,Cu)2ZnSn(S,Se)4 solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 3775 (2023).

Shi, J. et al. Multinary alloying for facilitated cation exchange and suppressed defect formation in kesterite solar cells with above 14% certified efficiency. Nat. Energy 9, 1095 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Pd(II)/Pd(IV) redox shuttle to suppress vacancy defects at grain boundaries for efficient kesterite solar cells. Nat. Commun. 15, 4344 (2024).

Wei, H. et al. Regulating Hetero-Nucleation enabling over 14% efficient kesterite solar cells. Small 20, e2308266 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. Controlling selenization equilibrium enables high-quality kesterite absorbers for efficient solar cells. Nat. Commun. 14, 6650 (2023).

Yin, K. et al. Lanthanum-induced synergetic carrier doping of heterojunction to achieve high-efficiency kesterite solar cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 9646, 11 (2023).

Zhou, J. et al. Control of the phase evolution of kesterite by tuning of the selenium partial pressure for solar cells with 13.8% certified efficiency. Nat. Energy 8, 526 (2023).

Nakamura, M. et al. Cd-free Cu (In, Ga)(Se, S) 2 thin-film solar cell with record efficiency of 23.35%. IEEE J. Photovolt. 9, 1863–1867 (2019).

Keller, J. et al. High-concentration silver alloying and steep back-contact gallium grading enabling copper indium gallium selenide solar cell with 23.6% efficiency. Nat. Energy 9, 467 (2024).

Chen, W., Stewart, J., Mickelsen, R., Devaney, W. & Stanbery, B. Research on Polycrystalline Thin-Film CuInGaSe2 Solar Cells: Annual Subcontract Report, 3 May 1991-21 May 1993 (United States, 1993).

Hadke, S. et al. Emerging chalcogenide thin films for solar energy harvesting devices. Chem. Rev. 122, 10170 (2022).

Krückemeier, L., Rau, U., Stolterfoht, M. & Kirchartz, T. How to report record open-circuit voltages in lead-halide perovskite solar cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1902573 (2019).

Gokmen, T., Gunawan, O., Todorov, T. K. & Mitzi, D. B. Band tailing and efficiency limitation in kesterite solar cells. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 103506 (2013).

Cuevas, A. The recombination parameter J0. Energy Procedia 55, 53 (2014).

Zhang, C., Zhang, J., Hao, Y., Lin, Z. & Zhu, C. A simple and efficient solar cell parameter extraction method from a single current-voltage curve. J. Appl. Phys. 110, 064504 (2011).

Tress, W. et al. Interpretation and evolution of open-circuit voltage, recombination, ideality factor and subgap defect states during reversible light-soaking and irreversible degradation of perovskite solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 11, 151 (2018).

Bourdais, S. et al. Is the Cu/Zn disorder the main culprit for the voltage deficit in kesterite solar cells?. Adv. Energy Mater. 6, 1502276 (2016).

Li, J., Yuan, Z.-K., Chen, S., Gong, X.-G. & Wei, S.-H. Effective and noneffective recombination center defects in Cu2ZnSnS4: Significant difference in carrier capture cross sections. Chem. Mater. 31, 826 (2019).

Gong, Y. et al. Sn4+ precursor enables 12.4% efficient kesterite solar cell from DMSO solution with open circuit voltage deficit below 0.30 V. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2005.11070 (2020).

Gong, Y. et al. Identifying the origin of the V oc deficit of kesterite solar cells from the two grain growth mechanisms induced by Sn 2+ and Sn 4+ precursors in DMSO solution. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 2369 (2021).

Rahman, M. Z. & Edvinsson, T. What is limiting pyrite solar cell performance?. Joule 3, 2290 (2019).

Park, J. S., Kim, S., Xie, Z. & Walsh, A. Point defect engineering in thin-film solar cells. Nat. Rev. Mater. 3, 194 (2018).

Unold, T. & Schock, H.-W. Nonconventional (non-silicon-based) photovoltaic materials. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 41, 297 (2011).

Yan, C. et al. Cu2ZnSnS4 solar cells with over 10% power conversion efficiency enabled by heterojunction heat treatment. Nat. energy 3, 764 (2018).

Yin, K. et al. Gradient bandgap enables >13% efficiency sulfide Kesterite solar cells with open-circuit voltage over 800 mV. Preprint at https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2404.00291 (2024).

Yan, C. et al. Beyond 11% efficient sulfide kesterite Cu2Zn x Cd1–x SnS4 solar cell: effects of cadmium alloying. ACS Energy Lett. 2, 930 (2017).

Tseberlidis, G., Gobbo, C., Trifiletti, V., Di Palma, V. & Binetti, S. Cd-free kesterite solar cells: State-of-the-art and perspectives. Sustain. Mater. Technologies 41, e01003 (2024).

Platzer-Björkman, C. et al. Back and front contacts in kesterite solar cells: state-of-the-art and open questions. J. Phys. Energy 1, 044005 (2019).

Ahmad, N. et al. Cadmium-free kesterite thin-film solar cells with high efficiency approaching 12%. Adv. Sci. 10, 2302869 (2023).

Wang, Z., Wang, Y., Taghipour, N., Peng, L. & Konstantatos, G. Ag-refined kesterite in superstrate solar cell configuration with 9.7% power conversion efficiency. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2205948 (2022).

Lanzoni, E. M. et al. The impact of Kelvin probe force microscopy operation modes and environment on grain boundary band bending in perovskite and Cu (In, Ga) Se2 solar cells. Nano Energy 88, 106270 (2021).

Li, J. et al. Unveiling microscopic carrier loss mechanisms in 12% efficient Cu2ZnSnSe4 solar cells. Nat. Energy 7, 754 (2022).

Mendis, B. et al. Nanometre-scale optical property fluctuations in Cu2ZnSnS4 revealed by low temperature cathodoluminescence. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 174, 65 (2018).

Kirchartz, T., Márquez, J. A., Stolterfoht, M. & Unold, T. Photoluminescence-based characterization of halide perovskites for photovoltaics. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1904134 (2020).

Green, M. A. Radiative efficiency of state-of-the-art photovoltaic cells. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 20, 472 (2012).

Siebentritt, S. et al. How photoluminescence can predict the efficiency of solar cells. J. Phys. Mater. 4, 042010 (2021).

Green, M. A. & Ho-Baillie, A. W. Pushing to the limit: radiative efficiencies of recent mainstream and emerging solar cells. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 1639 (2019).

deQuilettes, D. W. et al. Maximizing the external radiative efficiency of hybrid perovskite solar cells. Pure Appl. Chem. 92, 697 (2020).

Stolterfoht, M. et al. Visualization and suppression of interfacial recombination for high-efficiency large-area pin perovskite solar cells. Nat. Energy 3, 847 (2018).

Li, J. et al. Emergence of flexible kesterite solar cells: Progress and perspectives. Npj Flex. Electron. 7, 16 (2023).

Jean, J.; Brown, P. R. Emerging Photovoltaic Technologies. (IOP Publishing, 2020).

Acknowledgements

L.H.W. would like to acknowledge Singapore Ministry of Education (MOE) Tier 1 grant (RG155/23) and the Indonesian Endowment Fund for Education (LPDP) on behalf of the Indonesian Ministry of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, managed under the INSPIRASI Program (Grant No PRJ-61/LPDP/2022 and 612/E1/KS.06.02/2022).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.S.H. and L.H.W. conceived and conceptualized the perspective, building upon discussions with Z. Su, Q.M., H.X., S.W., G.L., and Z. Shao. S.S.H. performed the analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Q.M., H.X., S.W., and Z. Shao provided the data. All authors discussed the analysis and concepts and contributed inputs and perspectives. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hadke, S.S., Su, Z., Meng, Q. et al. Understanding efficiency losses from radiative and nonradiative recombination in Cu2ZnSn(S,Se)4 solar cells. Nat Commun 16, 8240 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63345-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63345-x