Abstract

Bayesian optimization (BO) helps in efficiently navigating complex and high-dimensional design spaces. Recently, it has been applied to materials science to discover novel materials with high performances. However, the application of BO to material design has been hindered by the challenges in handling discrete input variables, such as elements. This study introduces a novel element mapping strategy that encodes elemental identities into chemically meaningful continuous values, enabling the creation of easy-to-predict chemical spaces. This new framework is used to design high-capacity Na3V2(PO4)2F3 cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries, aiming to shift all working voltages into the desired operational voltage window (2.5–4.3 V). The proposed framework successfully suggested 16 optimal compositions within 50 iterations. The proposed approach can overcome the limitation of categorical input and broaden the applicability of BO to a wider range of material discoveries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

There is an increasing demand for novel high-performance materials. However, the traditional trial-and-error-based grid search experimental approaches employed to develop such materials are expensive and time consuming. To overcome these challenges, computational approaches such as density functional theory (DFT) calculations have been introduced1,2. In particular, high-throughput screening with DFT calculations has emerged as a method to rapidly explore large search spaces and identify promising candidate materials3. Recently, there have been remarkable advances in machine learning (ML), which enable direct prediction of material properties from their structural information, paving the way for a new era of data-driven material designs4,5,6,7.

Depending on the approach of feature extraction from structural data, many ML techniques have been developed. Among them, deep learning models based on graph neural networks (GNNs) have exhibited high accuracies. The GNN models represent atomic structures as graphs comprising nodes and edges, where nodes correspond to individual atoms and edges correspond to chemical bonds. By explicitly learning these atomic relationships from structural data, the GNN models effectively capture complex interactions between atoms, enabling accurate predictions of key material properties such as formation energy, binding energy, and electronic bandgap. Representative models, including CGCNN6 and M3GNet7, achieve state-of-the-art predictive performances by training on large datasets; these inherently rely on pre-existing datasets and require substantial computations for initial data acquisition.

Despite advances in property prediction, many studies still rely on grid search, which inevitably involves an exhaustive evaluation of the search space and carries fundamental inefficiencies. As design variables increase, the search space grows exponentially, making this approach increasingly prohibitive, particularly as many sampled points may be irrelevant to the target.

In contrast to grid search, Bayesian optimization (BO) offers a significantly improved efficiency in discovering optima by intelligently proposing evaluation points, and thereby reducing the number of required evaluations in high-dimensional search spaces8,9,10. BO utilizes a probabilistic ML model, often Gaussian processes (GPs)11, as a surrogate to predict the objective function and estimate the uncertainty within the observations. Based on the results of the surrogate model, the acquisition function proposes the next evaluation point.

Owing to these advantages, BO is an attractive method for materials research requiring an efficient optimization over complex and high-dimensional search spaces. For instance, BO has been successfully applied to optimize high-entropy alloy (HEA) compositions in electrocatalytic oxygen reduction reactions12 and multi-objective optimization of electrode manufacturing parameters for lithium-ion batteries13.

However, despite its efficiency, the direct application of BO to the design of new materials, including identification of novel combinations for doping elements, has remained largely unexplored. This limitation arises primarily because GPs—commonly employed surrogate models in BO—inherently assume continuous input variables, making it challenging to handle categorical or discontinuous variables such as elements. Although alternative surrogate models exist, they also struggle to handle high-dimensional categorical variables14,15.

To overcome this critical barrier, this study introduces a novel element mapping strategy that uniquely encodes elemental identities into chemically meaningful continuous values. Unlike conventional categorical encoding approaches such as one-hot encoding, ordinal encoding, or embedding-based encodings, our element mapping explicitly preserves the intrinsic chemical characteristics of elements. This enables BO to systematically and efficiently explore a previously inaccessible chemical space (search space) for materials discovery.

Further, this advanced material design strategy is applied to design cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries (SIBs)—an emerging alternative to lithium-ion batteries owing to their low cost and abundant sodium resources16,17,18. Among sodium superionic conductor (NASICON) structures19,20,21, Na3V2(PO4)2F3 (NVPF) has attracted a considerable attention owing to its high-rate capability and high working voltage22,23. However, the low capacity of NVPF remains a critical challenge.

One of the main reasons for low capacity (energy density) is that the sodium excess phase (Na4V2(PO4)2F3) formed by storing additional sodium-ions is thermodynamically unstable, despite the presence of spaces to store additional sodium-ions within the NVPF crystal structure. Consequently, the sodium excess phase cannot provide additional capacity because the working voltage is out of the general voltage window (2.5–4.3 V). In particular, deep sodiation below 2.5 V induces lattice distortion and phase transition from tetragonal to orthorhombic symmetry, accompanied by changes in vanadium oxidation states and weakened V–O/F bonding, leading to structural instability and capacity degradation24.

Here, we target the discovery of novel element combinations that replace vanadium in NVPF to obtain high capacity Na3M1(2.00–y)M2y(PO4)2F3 (NMPF). To this end, we aim to thermodynamically stabilize the sodium excess phase so that all working voltages are confined within the practical voltage window (2.5–4.3 V). By assigning chemically intuitive continuous values to elements, we construct a predictable and well-structured chemical space, significantly facilitating the efficient discovery of optimal element combinations with minimal evaluations. Our approach not only provides critical insights into the design of high-energy-density cathode materials but also highlights the broad applicability of our BO-guided framework for the efficient discovery of optimal element combinations, well beyond the limitations of conventional grid search or deep learning-based screening methods.

Results

Algorithm framework

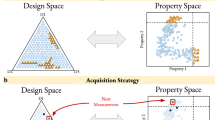

Figure 1 presents an overall schematic of the BO-based algorithm for discovery of optimal binary element combinations that stabilize the sodium-excess phase (Na4V2(PO4)2F3) of NVPF, repositioning all working voltages within the voltage window of 2.5–4.3 V. Although the lattice theoretically allows an additional sodium storage, forming a sodium-excess phase, the thermodynamic instability of this sodium-excess phase places its working voltage outside the operational voltage window (2.5–4.3 V), and thereby causes capacity loss. Stabilization of this sodium-excess phase by confining all redox reactions within the window of 2.5–4.3 V could significantly improve the energy density.

Discrete two-dimensional chemical space for exploring binary element combinations is transformed into continuous one through element mapping. Bayesian optimization is performed on the transformed chemical space. NMPF structures generated from the suggested element combination are evaluated based on the theoretical voltage profile. This process is iteratively repeated to discovery the optimal element combinations.

Generally, BO finds the optimal solution of an objective function by iteratively predicting with a surrogate model and suggesting the next guess with an acquisition function. GP are widely used as surrogate models in BO due to their ability to provide probabilistic predictions with uncertainty estimates. However, GP are designed for smooth and continuous functions25; therefore, it is challenging to identify optimal chemical components in discrete chemical spaces directly defined by elements. Furthermore, the method for construction of the chemical space is often unclear.

To address these issues, we introduce an element mapping technique. Element mapping involves assignment of each element to its continuous value, which transforms the discrete space directly created by the elements into a continuous space. The acquisition function in BO suggests specific values in the chemical space as its next guess. These values are then converted into an element combination with element mapping. Based on the proposed element combination, structures are created by considering all possible compositions rather than by optimization, as the number of possible cases is small. For example, from the eight sites for M1 and M2 in Na3M12.00-yM2y(PO4)2F3 (Fig. 2a), the possible chemical compositions replacing vanadium in NVPF are M11.75M20.25, M11.50M20.50, M11.25M20.75, M11.00M21.00, M10.75M21.25, M10.50M21.50, and M10.25M21.75. Single-point DFT calculations were performed for all ordering of M1 and M2 to define representative of them for each chemical composition, and the representative ordering of M1 and M2 were determined by comparing their relative energies. At this point, the sodium concentration of structure is fixed at Na3 because the NVPF after synthesis is basically Na3V2(PO4)2F3. The distribution of sodium and vacancies in the Na3M12.00-yM2y(PO4)2F3 structure was not considered but only the ordering of M1 and M2 was considered based on the basic structure shown in Fig. 1a. Based on the representative ordering of M1 and M2, the sodiation process is simulated through DFT calculations with structural relaxation to obtain theoretical voltage profiles based on Nernst equation26. In this work, to reduce computational load, a simplified sodiation process was simulated based on the structure shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 without considering the distribution of sodium and vacancies. These voltage profiles are then converted into single values using a scoring function (Fig. 2b, c). The highest score from various compositions and components represents the candidates of element combinations. The DFT calculation-based observation is added to the GP as training data, and the algorithm proposes the next guess as a potential element combination. The algorithm iterates this process to find the optimal element combinations within a given number of observations.

a Crystal structure of NVPF. b DFT calculation-based theoretical voltage profiles of pure NVPF and Ag- and Pt-substituted NVPF. Scoring function in c one dimension and d two dimensions. e Unary scores of the substituted NVPF with 9 example elements. f Regions defined with the median of the unary scores. g normalized unary score.

Preprocess of Bayesian optimization

Figure 2 shows details of the scoring function and element mapping. NVPF structures with different sodium concentrations (Na1V2(PO4)2F3, Na2V2(PO4)2F3, Na3V2(PO4)2F3, and Na4V2(PO4)2F3) are labeled as Na1, Na2, Na3, and Na4, respectively (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1). DFT calculations were performed for structures with different sodium concentrations, and theoretical voltage profiles were derived with the Nernst equation (Fig. 2b). In this study, a simplified sodiation process was performed, considering only integer Na stoichiometry to reduce computational load. The working voltages in the theoretical voltage profiles for the (Na1, Na2), (Na2, Na3), and (Na3, Na4) structures are specified as V12, V23, and V34, respectively. To create a criterion for the BO to evaluate voltage profiles from suggested element combinations, we define a scoring function (Fig. 2c). The scoring function gives a penalty when the working voltage deviates from the voltage window. When the working voltage is within the voltage window, the scoring function returns zero as the highest score. The total score of the voltage profile is defined as the sum of the scoring function values of V12, V23, and V34. Supplementary Fig. 2 shows the scoring function in two dimensions, constructed with V12 and V34 and the black dashed line box indicates the zero-score range area, where the total score equals zero. In the practical optimization process, a three-dimensional scoring function is formed through a scoring function with V12, V23, and V34. This scoring method aims to identify the optimal element combination that brings all working voltages of the structure within the zero-score range.

Definition of unary score

To successfully find the optimal element combinations with the minimum number of observations, the chemical space defined by the input and scoring function (output) should be easy to predict. This implies that there should be fewer regions with steep gradients within the chemical space. To create an easy-to-predict chemical space, the input and scoring function should be highly correlated to avoid abrupt gradient regions. Because the scoring function evaluates the position of working voltage, the scoring function is highly connected to the sodiation process. Therefore, the input should be correlated with the sodiation process.

Here, we introduce a unary score (S) as an appropriate input. The unary score represents the evaluation of a structure in which all vanadium atoms in NVPF are substituted with the candidate element. To explain the definition of the unary score, we present the following example. Figure 2d shows the theoretical voltage profiles of a fully substituted NMPF, where only a single transition metal (Na3M2(PO4)2F3) is substituted from 9 candidates (including vanadium). Each voltage profiles in Fig. 2d are converted to single values (score) by evaluation with defined scoring function. Because the substitution involves only one element, this value is referred to as the unary score. Consequently, each transition metal can be quantified by a specific unary score, which contains information about the sodiation behavior of NMPF when vanadium is replaced by the transition metal. In this way, it is possible to capture the properties of the sodiation process as a value when the element is within the framework of an NVPF.

Creation of chemical space with element mapping

To create continuous chemical space which can be adopted to GP in BO, we introduce element mapping technique which is assigning the continuous value to element. Figure 2e shows the unary scores obtained above arranged on a horizontal line with their corresponding elements. Based on the medians between the unary scores (black dashed vertical line in Fig. 2e), the range for each element is defined (Fig. 2f). Through this process, the elements are transformed into a continuous space, meaning can be adopted to GP. Now, if GP proposes a value corresponding to −3.5 as the next observation point, since −3.5 is in the range of Ti (and is closest to Ti), Ti is selected as the element for the next observation. Since the intervals of the range are different, rough regions in chemical space can be formed. Therefore, the ranges of each element are normalized (equally spaced) (Fig. 2g). In this study, each range was normalized with an interval of 1. In terms of providing input to the GP, the absolute value is not important, so the starting point was set to zero.

One of the distinctive features of element mapping is any value that can represent an element can be used mapping, even if it is not the unary score. One example is the electronegativity, which represents the tendency to attract electrons and is already used as an input in ML models27,28,29. Because the role of transition metals in NMPF is to store electrons during the sodiation process, the electronegativity can be useful for element mapping. However, the unary score has a higher correlation with the scoring function than the electronegativity. The unary score provides a direct assessment of the role for a transition metal within the NVPF environment, capturing aspects beyond those that can be revealed by the electronegativity alone. It also accounts for relaxation effect which represents the geometric contribution of structure that is reflected in its energy during the DFT calculations with structural relaxation, and alterations in the electronic structure.

To investigate how the correlation between the sodiation process and input facilitates the prediction of chemical space, we additionally introduce electronegativity (X) and atomic number (Z) as mapping features. Atomic number is used as an example to show less relevant factor in the sodiation process. With 35 candidate elements, the chemical spaces are created with normalized unary score (Snorm), normalized electronegativity (Xnorm), and normalized atomic number (Znorm), based on introduced element mapping technique (Supplementary Figs. 3–5).

Bayesian optimization for optimal binary element combination

Figure 3 shows the process and results of exploring the optimal binary element combinations in a two-dimensional continuous chemical space transformed with element mapping by normalized unary score (Snorm). The chemical space is formed with 35 elements. The total number of cases is 630 (35C1 + 35C2). To verify that the algorithm remains robust even under more difficult conditions, the Bayesian optimization was performed without any initial training data. At 10th, 30th, and 50th iterations, the mean (μ) and normalized standard deviation (σnorm) of the predictions from the GP (surrogate model) are visualized as the predicted chemical space (Fig. 3a) and the uncertainty of prediction (Fig. 3b). In the visualization process, the maximum and minimum values in the chemical space are set to 0 and −5, respectively. The uncertainty (σ) for each iteration was normalized between 0 and 1 to identify relative trend. In the predicted chemical space at the 10th iteration step, there is a preliminary tendency for low-Snorm regions to have low scores and high-Snorm regions to have high scores. As the iterations progress, the trend becomes clearer. There are more observations in the high-S region with high scores rather than in the low-S region. This implies that the exploitation to observe near the high-score observations progressed properly.

a Predicted chemical space at 10th, 30th, and 50th iterations. b Uncertainty (σnorm) at 10th, 30th, and 50th iterations. White circles and yellow stars indicate observations and optimal points, respectively. The predicted score and uncertainty are represented by colors. c Ground truth defined by the collected observation data. A white area indicates an empty point. d R2 of the predicted chemical space at each iteration.

As the iterations progress, the uncertainty within the chemical space is reduced. Specifically, at the 50th iteration, the uncertainty of the low-Snorm region is still high, and there are relatively few observations. This implies that the algorithm has primarily explored high-Snorm regions, which demonstrates the exploitation by focusing on areas with high scores. In addition, as there are observations in the 50th iteration in areas where the algorithm already judged the score to be low at the 30th iteration, it can be inferred that there has been progress in exploration as well as exploitation. In case of optimization with element mapping by Snorm, 16 optimal points are discovered, and 14 element combinations are discovered without overlapped element combinations (Os-Pb, Pd, Hf-Pd, Mo-Pd, Pd-V, Mn-V, Pd-Re, Mo-Pd, Ag-Ru, Pd-W, Co-Ir, Pb-Pd, Co-V, and Pd-Ta). A total of 24 compositions are included in element combinations. To validate the results, the voltage profiles of the 24 optimal compositions were recalculated using tight convergence criteria in the DFT calculations. Compared to the results obtained using loose convergence criteria during Bayesian optimization, the mean squared errors in voltage and score for the 24 compositions were 0.034 V and 0.013, respectively. Due to these shifts, 16 compositions were finally confirmed to have working voltages within the target voltage window (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6a).

To evaluate the accuracy of the surrogate model, the ground truth is defined with the obtained observation data (Fig. 3c). Unobserved data are considered as empty points. A qualitative comparison of the predicted chemical space at iteration 50 with the ground truth shows a similar trend of higher scores in the rightward direction. Additionally, by measuring R2 between the predicted chemical space and ground truth per iteration step, the quantitative accuracy was identified (Fig. 3d). R2 increases until around the 10th iteration, and then gradually decreases to the 35th iteration. As shown in the predicted chemical space at the 30th iteration in Fig. 3a, the low R2 value is attributed to the lack of observations in the low-Snorm region. This leads to a large difference in the low-Snorm region of the predicted chemical space and ground truth. However, after the exploratory observations in the low-Snorm region, R2 is suddenly increased and a high R2 is achieved (0.730 at the 50th iteration).

To understand the differences in constructing the chemical space with the different inputs, the two-dimensional chemical spaces were constructed with Xnorm and Znorm. Supplementary Figs. 7a, 8a show the predicted chemical spaces corresponding to each iteration step by the surrogate model, while Supplementary Figs. 7b, 8b show the uncertainties of their predictions. In chemical space created by Xnorm, Bayesian optimization results revealed 9 optimal points (Ag-Pt, Au-Mo, Au-Nb, Cr-Rh, Ir-Pb, Mn-Pb, Mo-Tl, Pb-Pt, and Pd-Re) without overlaps. In the optimal points, 12 compositions are included within these element combinations. In the case of Znorm, 7 optimal points are discovered (Au-Mo, Au-Ta, Hg-Ru, Mo-Tl, Os-Pb, Pd-Pd, and Pd-Re). Among these, 12 compositions are included. In both cases, 9 and 6 optimal compositions are confirmed by validation with the tight convergence criteria-based DFT calculations (Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6).

For each case, the comparison of the predicted chemical space at the 50th iteration with the ground truth (Supplementary Figs. 7c, 8c) shows a large number of differences. In particular, for Xnorm, despite the overall low uncertainty at the 50th iteration, there is a large difference with respect to the ground truth, indicating that the model misunderstands the trend of the chemical space (white dashed box in Supplementary Fig. 7a). In Supplementary Fig. 7d, R2 remains around -0.25 until the 20th iteration, after which it decreases sharply, becoming very low near the 30th iteration and increasing later. However, it still has a negative R2 at the 50th iteration. Likewise, in the case of Znorm, R2 remains around 0.15 and does not increase with the iterations (Supplementary Fig. 8d). This is also because regions significantly deviating from the ground truth were discovered within the predicted chemical space (black dashed box in Supplementary Fig. 8a). This implies that the surrogate model does not capture the trends of the chemical space correctly, which results in predictions that deviate significantly from the ground truth. However, despite very low prediction accuracy for Xnorm and Znorm (even negative R2), the algorithm was able to find some optimal points. The reason is that the GP successfully predicted certain local regions with high scores in each case. This enabled the algorithm to find optima within local regions. However, it failed to predict globally, thus missing optima distributed in other regions.

Furthermore, to examine the dependence of the optimization results on the initial observations with random state, Bayesian optimization was independently performed using three different mapping features (Snorm, Xnorm, and Znorm) with different random states, denoted as 0, 1, and 2 (Supplementary Figs. 9–14). Supplementary Fig. 15 shows the number of discovered optimal compositions with different mapping features and random states. The results revealed that the number of optima did not vary significantly with initial observations, confirming the consistency of the performance of proposed algorithm.

The difference in the number of discovered optimal points (16 for Snorm, 9 for Xnorm, and 7 for Znorm) and accuracy is mainly due to the difficulty of exploring chemical space. Because the GP is designed for smooth and continuous functions, it is hard to predict highly rough functions. Figure 4a, Supplementary Fig. 16a, c show the morphology of each chemical spaces. The empty points in the chemical space are filled with the average values of their neighbors. The morphology of the chemical space formed with Snorm (Fig. 4a) shows qualitatively a low complexity and high smoothness compared to the others (Supplementary Fig. 16a, c). In the chemical space constructed with Snorm, there are fewer sharp differences of score in neighboring areas. In addition, the high-score points (optimal points) are clustered. However, the chemical space formed with Xnorm and Znorm shows a large difference in scores in neighboring area, and their morphology is more complex. To analyze the difference quantitatively, we defined and visualized the RMSG with Eq. (1), which quantifies the gradient between the point and its neighbors in each chemical space (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Fig. 16b, d).

where \({M}_{i,{j}}\) refers to the value at the \((i,{j})\) position within the matrix (chemical space), while \(N\) is the number of neighbors. In Fig. 4b, there are fewer large gradients compared to the others (Supplementary Fig. 16b, d). In addition, in the case of S, the average and standard deviation of RMSG (0.25 and 0.16) are smallest compared to the others (0.48 and 0.39 for Xnorm and 0.34 and 0.26 for Znorm, respectively). This implies that the chemical space with Snorm is smoothest and easiest to predict. The difference in difficulty is caused by the correlation between the output of the chemical space, scoring function, and input. The scoring function is strongly related with the sodiation. Therefore, because the unary score is strongly related to the sodiation, it is possible to construct a chemical space with the certain tendency providing a smooth chemical space.

Effectiveness of the proposed algorithm

To confirm the effectiveness of applying BO in finding optimal element combinations, we compared our results with those of a deep learning-based screening study5. In a previous study, the deep learning model (MEGNet) predicted the DFT energy of NaxM12.00-yM2y(PO4)2F3 (NMPF) in a chemical space formed with 30 elements where the total number of cases is 465 (30C1 + 30C2) (Supplementary Fig. 17b). In previous work, working voltage was measured based on predicted energy and evaluated with the criterion (V12 – V34)/V34, where lower values indicate the optimal state, to identify promising element combinations.

In order to compare quantitatively with previous studies, the predicted energy-based voltage was evaluated using the scoring function (Fig. 2c). Because the candidate elements for constructing the chemical space are different, we only consider overlapping elements in the candidate elements of each study (Supplementary Fig. 17). For the previous study, a total of 27 predicted optimal points is found. However, after the validation process with DFT calculations with the tight convergence criteria, there are only four optimal binary compositions (Au1.25Mo0.75, Au1.50Fe0.50, Pd1.25Ru0.75, and Pd1.50Ru0.50) and three element combinations (Au-Mo, Au-Fe, and Pd-Ru in Fig. 5b). In contrast, the Bayesian approach discovered a total of 11 optimal binary compositions (Pd1.75Re0.25, Pd1.75W0.25, Mo0.50Pd1.50, Pd1.50Re0.50, Pd1.25V0.75, Hf0.50Pd1.50, Pd1.50Ta0.50, Co0.75Ir1.25, Co1.00Ir1.00, Co0.50V1.50, and Mn0.75V1.25) and 9 element combinations (Pd-Re, Pd-W, Mo-Pd, Pd-V, Hf-Pd, Pd-Ta, Co-Ir, Co-V, and Mn-V). This result shows that the proposed algorithm is more effective in terms of finding more optima (Fig. 5).

The difference in the number and kinds of discovered optimal points is caused by the different mechanisms for finding optima in each approach. The approach of the previous study observes all points in the grid with predictions from a ML model. This approach has the advantage of quickly exploring the entire chemical space. However, due to an error of the ML model-based prediction, the number of optimal points is reduced after validation at the DFT level. In contrast, BO finds the optima by suggesting the next guess based on previous DFT-level observations obtained through direct DFT calculations. This allows it to find as many optimal points as possible within a given number of observations. However, as it proceeds from a given number of observations (e.g., 50 iterations out of a total of 630 points), there is a limit in finding all optimal points in the chemical space. Also, each execution of BO may lead to different results depending on the initial starting points. These limitations are expected to be addressed by conducting several BOs.

To confirm the feasibility of application to higher dimensions (complex structures), a three-dimensional chemical space for the discovery of ternary optimal element combinations was constructed with Snorm. Specifically, a total of 100 data points is randomly selected from both unary and binary data (Supplementary Fig. 18a). GP model with same computational details is trained with the data. Mean (μ) and normalized standard deviation (σnorm) were used to assess the predicted chemical space and uncertainty. To visualize the three-dimensional space, cross-sections were plotted at regular intervals along the x-axis (Supplementary Fig. 18b, c). Similar to the case of two-dimensional chemical space, the region with lower Snorm exhibit lower scores, while those with larger Snorm show higher scores. Due to the lack of ternary data, it is difficult to conduct precise evaluation. Therefore, the accuracy for x = y plane where x and y values are equal (comparable to a two-dimensional space, Supplementary Fig. 18a) was evaluated with R2, which was found to be 0.68. Although the results may not be entirely precise since the three-dimensional chemical space was formed solely from binary and unary element combinations without considering synergies between ternary element combinations, a relatively high R2 was indirectly measured. These results suggest that, just as the GP successfully predicted the two-dimensional chemical space formed by Snorm and discovered many optimal points, it would also be capable of finding the optimal points in the three-dimensional space. Based on this result, it is believed that finding optimal ternary element combinations in three-dimensional chemical space is feasible.

Analysis with DFT calculations

To understand how the discovered optimal element combinations function in NVMF, their electronic properties were analyzed using DFT calculations. Considering the theoretical energy density, cost, and toxicity, Mn0.75V1.25 and Co0.50V1.50 are derived as suitable element combinations (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 19). To determine the degree of electron acceptance on the NMPF according to the sodium concentration, a Bader charge analysis30 is performed to investigate the degree of charge transfer. Figure 6b and Supplementary Fig. 20 show the total amount of charge transferred to the element combination for the discovered NMPF. In all cases, the total amount of charge transferred to the element combination in NMPF is higher than the transferred charge of the NVPF (V2.00). Put simply, the element combination in NMPF accepts more electrons than the vanadium center in NVPF. This implies that one of the conditions for working voltages to be within the voltage window is to accept more electrons than vanadium during sodiation. Figure 6c, d and Supplementary Fig. 21 show the atomic Bader charge analysis of the NMPF with element combinations containing vanadium (Mn0.75V1.25, Co0.50V1.50, and Pd1.25V0.75). The rhombus represents the charge transferred to each transition metal, while the black line represents the average value of the transferred charge of V in NVPF (V2.00). The amount of charge transferred to vanadium in the Na1, Na2, and Na3 phases is similar to the transferred charge of pure NVPF (V in V2.00), but there is a difference in the Na4 phase. This suggests that the formation of Na4 (sodium excess phase) is unstable due to a large amount of transferred charge to vanadium. However, the NMPF with the optimal element is energetically stable owing to the transfer of charge to a substituted transition metal that can more readily accept the charge rather than vanadium.

Discussion

In this study, we propose an algorithm to discover element combinations, which addresses the limitation of the GP in BO. By assigning elements to continuous values through element mapping, it is possible to construct a chemical space for BO application.

The main advantage of the proposed algorithm is its capability to effectively navigate low-dimensional chemical spaces with limited observations. Unlike deep learning-based grid search methods, our approach does not require initial training data and additional resources for training. Moreover, it is flexible and scalable to a wide range of material systems by appropriately defining the scoring function and input.

Through its application, we identified 16 optimal combinations of elements in just 50 iterations and designed high‑capacity NASICON‑type cathode materials for sodium‑ion batteries—Mn0.75V1.25 and Co0.50V1.50—which successfully stabilize the sodium‑excess phase of NVPF.

This new framework presents a robust, extensible, and flexible platform for data‑driven material design by combining BO and element mapping. It uses chemically intuitive unary scores—continuous descriptors derived from DFT—to bypass large training datasets and enable mechanistic interpretability. Consequently, it will drive a rapid convergence in discrete chemical spaces and accelerate the discovery across diverse material classes, opening new avenues for future data‑driven discovery.

Methods

DFT calculations

Using the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP)31 with the projector-augmented wave (PAW) scheme and spin polarization, calculations were conducted according to the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) formulation32. A plane-wave expansion of wave functions was set with a cutoff energy of 500 eV. The Monkhorst–Pack method33 employing a 1 × 1 × 1 k-point grid was utilized. The convergence criteria for electronic and ionic steps in DFT calculations during observations in BO were 1.0 × 10−4 eV and 1.0 × 10−3 eV, respectively. For the validation of the NMPF with discovered element combinations, the convergence criteria were set at 1.0 × 10−6 eV and -0.02 eV/Å. Hubbard U terms of 3.1, 3.5, 4.0, 4, 3.3, 6.4, 4.0, and 7.5 were applied to V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, and Zn, respectively34,35,36. The crystal structures were drawn with the software VESTA37.

Bayesian optimization

In the BO algorithm, GP25, which is a probabilistic ML model, was used as a surrogate model with the Matérn11 kernel (ν = 5/2) to consider step-like morphology of the chemical space. An upper confidence bound algorithm38 was employed for the acquisition function, which determines the maximum value of the upper bound on the uncertainty from GP regression. To balance exploration and exploitation, the kappa (κ) was set to 2.575, the default value in the Bayesian Optimization Python package39, which was used to build our algorithm.

The scoring function (Fig. 2c) is defined as follows:

where V is theoretical working voltage obtained by DFT calculations.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Code availability

The code for our Bayesian optimization with element mapping is available at https://github.com/mutsang73/BOEM.

References

Agrawal, A. & Choudhary, A. Perspective: materials informatics and big data: realization of the “fourth paradigm” of science in materials science. APL Mater. 4, 053208 (2016).

Urban, A., Seo, D.-H. & Ceder, G. Computational understanding of Li-ion batteries. npj Comput. Mater. 2, 16002 (2016).

Greeley, J. et al. Computational high-throughput screening of electrocatalytic materials for hydrogen evolution. Nat. Mater. 5, 909–913 (2006).

Chen, C. et al. Graph networks as a universal machine learning framework for molecules and crystals. Chem. Mater. 31, 3564–3572 (2019).

Shim, Y. et al. Data-driven design of NASICON-type electrodes using graph-based neural networks. Batter. Supercaps 7, e202400186 (2024).

Xie, T. & Grossman, J. C. Crystal graph convolutional neural networks for an accurate and interpretable prediction of material properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 145301 (2018).

Chen, C. & Ong, S. P. A universal graph deep learning interatomic potential for the periodic table. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 718–728 (2022).

Brochu, E., Cora, V. M., & Freitas, N.d. A tutorial on Bayesian optimization of expensive cost functions, with application to active user modeling and hierarchical reinforcement learning. arXiv:1012.2599, 2010.

Frazier, P. I., A tutorial on Bayesian optimization. arXiv:1807.02811, 2018.

Snoek, J., Larochelle, H., & Adams, R. P. Practical Bayesian optimization of machine learning algorithms. arXiv:1206.2944, 2012.

Rasmussen, C. E. & Williams, C. Gaussian Processes for Machine Learning (MIT Press, 2006).

Pedersen, J. K. et al. Bayesian optimization of high-entropy alloy compositions for electrocatalytic oxygen reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 60, 24144–24152 (2021).

Duquesnoy, M. et al. Machine learning-assisted multi-objective optimization of battery manufacturing from synthetic data generated by physics-based simulations. Energy Stor. Mater. 56, 50–61 (2023).

Mohammadi, H., P. Challenor, M. Goodfellow, and D. Williamson, Emulating computer models with step-discontinuous outputs using Gaussian processes. arXiv:1903.02071v4, 2020.

Luong, P. et al. Bayesian optimization with discrete variables, in AI 2019. Advances in Artificial Intelligence. (2019) p. 473–484.

Hwang, J. Y., Myung, S. T. & Sun, Y. K. Sodium-ion batteries: present and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 3529–3614 (2017).

Zhao, L. et al. Engineering of sodium-ion batteries: opportunities and challenges. Engineering 24, 172–183 (2023).

Xiang, X., Zhang, K. & Chen, J. Recent advances and prospects of cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Mater. 27, 5343–5364 (2015).

Xu, C. et al. A novel NASICON-typed Na4VMn0.5Fe0.5(PO4)3 cathode for high-performance Na-ion batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 11, 2100729 (2021).

Zhu, C. et al. A high power–high energy Na3V2(PO4)2F3 sodium cathode: investigation of transport parameters, rational design and realization. Chem. Mater. 29, 5207–5215 (2017).

Anantharamulu, N. et al. A wide-ranging review on Nasicon type materials. J. Mater. Sci. 46, 2821–2837 (2011).

Wang, M. et al. Synthesis and electrochemical performances of Na3V2(PO4)2F3/C composites as cathode materials for sodium ion batteries. RSC Adv. 9, 30628–30636 (2019).

Yan, G. et al. Higher energy and safer sodium ion batteries via an electrochemically made disordered Na3V2(PO4)2F3 material. Nat. Commun. 10, 585 (2019).

Mani Kanta, P. L. et al. Outstanding specific energy achieved via reversible cycling of V4+/V2+ redox couple in N-doped carbon coated Na3V2(PO4)2F3: An ex-situ XRD, XPS and XAS study. Mater. Today Energy 48, 101802 (2025).

Gramacy, R. B. Surrogates-Gaussian Process Modeling, Design, and Optimization for the Applied Sciences (CRC Press, 2020).

Bai, Q. et al. Computational studies of electrode materials in sodium-ion batteries. Adv. Energy. Mater. 8, 1702998 (2018).

Zhao, D. et al. Machine-learning-assisted modeling of alloy ordering phenomena at the electronic scale through electronegativity. Appl. Phys. Lett. 124, 111902 (2024).

Li, Z., Ma, X. & Xin, H. Feature engineering of machine-learning chemisorption models for catalyst design. Catal. Today 280, 232–238 (2017).

Noh, J. et al. Active learning with non-ab initio input features toward efficient CO2 reduction catalysts. Chem. Sci. 9, 5152–5159 (2018).

Tang, W., Sanville, E. & Henkelman, G. A grid-based Bader analysis algorithm without lattice bias. J. Phys. Condens. Matter. 21, 084204 (2009).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 169–186 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Monkhorst, H. J. & Pack, J. D. Special points for Brillouin-zone integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13, 5188–5192 (1976).

Dudarev, S. L. et al. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: an LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Wang, L., Maxisch, T. & Ceder, G. Oxidation energies of transition metal oxides within the GGA+U framework. Phys. Rev. B. 73, 195107 (2006).

Harun, K. et al. DFT + U calculations for electronic, structural, and optical properties of ZnO wurtzite structure: a review. Results Phys. 16, 102829 (2020).

Momma, K. & Izumi, F. VESTA: a three-dimensional visualization system for electronic and structural analysis. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 41, 653–658 (2008).

Agrawal, R. Sample mean based index policies with O(log n) regret for the multi-armed bandit problem. Adv. Appl. Probab. 27, 1054–1078 (1995).

Nogueira, F. Bayesian Optimization: Open source constrained global optimization tool for Python. GitHub repository, 2014. Available at: https://github.com/bayesian-optimization/BayesianOptimization.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Nano & Material Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (RS-2024-00449682) and Yangyoung Foundation in 2025.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.P., J.M.Y. and C.-W.L. designed research. S.P., Y.S. and D.J. conducted DFT calculations. S.P. and Y.S. analyzed the difference between Bayesian approach and deep learning-based approach. J.H. and S.J. analyzed the morphology of created chemical spaces. S.P., J.M.Y. and C.-W.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Park, S., Shim, Y., Hur, J. et al. Element mapping-based Bayesian optimization framework enabling direct materials design: a case study on NASICON-type cathode materials. npj Comput Mater 12, 92 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-026-01958-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-026-01958-6