Abstract

Dislocation dynamics at the atomic scale play a significant role in phase transformations and mechanical degradation of layered cathode materials in Na-ion batteries (NIBs), yet their fundamental behavior remains poorly understood. Here, we employ first-principle calculations to investigate dislocation-mediated processes in a range of O3- and O'3-type layered transition metal (TM) oxides, Na(TM)O₂, with TM = Ti, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, and Ni. Generalized stacking fault \(\gamma\)-surfaces are computed to quantify the influence of TM chemistry on stacking sequence energetics. These \(\gamma\)-surfaces, combined with elastic tensor data, inform a semi-discrete variational Peierls–Nabarro model to characterize dislocation core structures and Peierls stresses. Our results reveal narrow dislocation cores and partial splitting behaviors governed by the γ-surface topology and material elasticity. We further propose a dislocation-driven mechanism for the O3\(\leftrightarrow\)P3 phase transformation, wherein partial dislocation motion facilitates the broadening of stacking faults during desodiation. This work establishes a detailed first-principles computational framework for understanding dislocation-mediated degradation pathways in layered oxides, offering atomistic-scale insights for the design of more robust NIB cathode materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Understanding dislocation formation and structure is fundamental to advancing a broad range of structural and functional materials across multiple industries. In metallurgy, dislocations have been extensively studied for their critical role in controlling mechanical strength and deformation, making them central to virtually all engineering sectors1,2. These considerations also extend to energy materials, where dislocations influence key material properties. For example, in metallic alloys used for nuclear energy applications, dislocations govern microstructural evolution under irradiation, directly impacting material stability and lifetime3. Similarly, in thermal energy storage systems, dislocations affect corrosion of nickel superalloys, influencing their durability4. Dislocations also play a crucial role in non-metallic compounds such as crystalline silicon, where their presence is among the most significant factors limiting the conversion efficiency of solar cells5. In battery materials, dislocation activity has been directly linked to key degradation phenomena such as phase transitions, voltage fade, and mechanical failure modes6,7,8,9. Controlling dislocations through defect engineering has also been proposed as a strategy to optimize Li-ion battery (LIB) performance10,11,12. However, despite their critical role, the mechanistic and atomistic understanding of dislocation dynamics in these materials remains limited.

This knowledge gap is especially relevant for emerging battery technologies like Na-ion batteries (NIBs), that hold the potential to address growing concerns regarding supply chain security and sustainability13,14. This is due to the natural abundance of sodium, the use of cost-effective materials like aluminum as current collectors15,16, and to the one-to-one correspondence between the manufacturing process of NIBs and LIBs at industrial scale, which has facilitated a faster path to commercialization17, as evidenced by the emergence of the first generation of commercial NIBs18,19. This development has promoted a surge in experimental and modelling efforts to better understand their performance and degradation mechanisms20,21,22,23. However, the mechanistic atomic-level understanding of many of these degradation processes remains elusive.

At the materials level, NIB cathodes primarily fall into two structural families: polyanionic frameworks24 and layered oxides25. Amongst these, the latter ones are particularly attractive due to their high capacities and synthesis scalability. Their crystal structure is typically categorized as O\(n\) and P\(n\) phases26,27, where “O” or “P” refers to the coordination environment of sodium with oxygen (octahedral or prismatic, respectively), and \(n\) indicates the number of formula units per unit cell. Similar to LIBs, the active redox centers in NIBs are 3 d transition metals (TMs) arranged in edge-sharing octahedral layers. Optimizing the composition of these TM layers has been the subject of extensive research28,29. However, achieving long-term structural stability remains a major challenge, mainly due to the reversible O\(\leftrightarrow\)P phase transformations that occur during sodium (de-)intercalation. These transformations involve changes in stacking sequences within the TM-O layers, which can lead to structural collapse and capacity fade if not properly controlled.

Specific TM mixtures and dopants have been shown to stabilize reversible O3\(\leftrightarrow\)P3 transformations30 or even suppress them altogether31. Similarly, synthesizing low-strain, defect-free materials can delay the onset of structural degradation32. Still, repeated stacking sequence changes inevitably introduce internal strain, leading to electrochemical creep by lattice-invariant shears33. This, in turn, can produce irreversible phases and microcracks that degrade battery performance34,35. Thus, a deeper understanding and control of these stacking transformations are critical to ensure a stable cycling and enhance the performance of layered TM oxides36.

Crucially, these stacking sequence changes are not rigid atomic movements but are often mediated by dislocation nucleation and glide. Dislocations enable shearing at much lower stresses than required for rigid shifts, making them key actors in these structural changes. For example, Gabrisch et al.37 identified Schokley partial dislocations bounded by intrinsic stacking faults (ISF) in O3-LiCoO2 and proposed that their glide underpins O3\(\leftrightarrow\)H1-3\(\leftrightarrow\)O1 transformations, where H1-3 refers to O1/O3 intergrowth. Similar mechanisms have been observed in Ni-rich LIB cathodes, where repeated cycling resulted in roughened particles providing direct evidence for lattice-invariant shears38. Dislocations also play a role in driving other degradation modes unrelated to planar gliding. For example, dislocations with Burgers vector components perpendicular to the TM-O layers contribute to voltage fade6, oxygen release9, and intragranular cracking7 by the formation of extrinsic stacking faults (extra half-planes) parallel to the TM layers, which can also induce stacking ordering mixtures. Recently, Kumakura et al. 39 unlocked highly reversible cycling in corrugated TM-O layered \(\beta\)-NaMnO2 phase by suppressing stacking fault formation using Cu doping, which corresponds to the gliding of partial dislocations with Burger’s vectors perpendicular to the TM layers. They also observed TM-layer stacking sequence changes during the charge/discharge process.

Despite the clear significance of dislocations in determining the structural and electrochemical stability of battery cathodes, the field lacks comprehensive atomistic studies of their structure and behavior in layered TM oxides, with few works focusing on indirect measures for dislocation glide40,41 and a recent effort by Sadowski et al. 42 to atomistically describe a screw dislocation and its associated properties (e.g., structure, energetics, and vacancy interactions). To bridge this gap, the present work aims to provide an atomistic understanding of dislocation properties in O3-type layered Na(TM)O2 oxides using a combination of density functional theory (DFT) and a semi-discrete variational Peierls–Nabarro (SDVPN) framework. The study characterizes both edge and screw dislocations for a range of technologically relevant TMs including Ti, Cr, Fe, and Co (in the spacegroup \({\rm{R}}\bar{3}{\rm{m}}\)), as well as Jahn-Teller (JT) active Mn and Ni in their monoclinic O´3-type derivatives (spacegroup \({\rm{C}}2/{\rm{m}}\)), all focused on the (0 0 1) slip plane parallel to the TM-O layers. DFT-derived parameters such as generalized stacking surface (GSF) energies and elastic tensor coefficients are used to inform the SDVPN model43,44, allowing for detailed insights into the energetics and mechanics of dislocation motion. These findings offer a critical step toward a more complete understanding of dislocation-mediated degradation in materials relevant to next-generation NIBs. The complete description of the methodology can be found at the Methods section.

Results

Generalized Stacking Fault Surfaces

The study of GSF energy surfaces, \(\gamma ({\boldsymbol{r}})\), (see Methods section for more details) is fundamental to understanding plastic deformation in crystalline materials, yet their implications for mechanical damage and failure mechanisms in battery materials remain largely unexplored. In a previous study, we analyzed glide-driven P2\(\leftrightarrow\)O2 phase transformations in NaxVO2 (0 < x < 1) using the climbing-image nudged elastic band (CI-NEB) method41. We focused on the specific gliding vectors \({\boldsymbol{r}}\) connecting the atomic arrangements of the P2 and O2 phases. Concurrently, Kaufman et al. computed the complete GSF energy surfaces for O3-type LiCoO2 and NaCoO2, as well as O1-type delithiated CoO2. They identified an intrinsic P3-type stacking fault configuration in the Na-containing structure, suggesting the possibility of O3\(\leftrightarrow\)P3 and P3\(\leftrightarrow\)O1 transitions. In contrast, the P3 structure was found to be an unstable stacking fault in LiCoO240. Shorly after, Sadowski et al. used the CI-NEB method to calculate the energy barriers associated with specific gliding vectors r in LixCoO2 and LixNiO2 (0 < x < 1), as well as in NixO2 (x = 1, 1.02). Their work revealed how Li content and Ni substitution in the Li layer influence the relative stability and energy barriers for O3↔O1 phase transformations42.

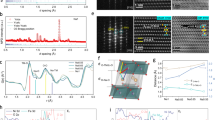

In this study, we extend the analysis to full γ-surfaces for O3-Na(TM)O2 layered structures containing Ti3+, Cr3+, Fe3+, and Co3+, as well as their monoclinic O‘3 type counterparts containing Mn3+ and Ni3+, as shown in Fig. 1. All investigated structures exhibit ISF \(({\gamma }_{{ISF}})\), corresponding to local minima in the GSF energy landscape (denoted by an asterisk in Fig. 1). Notably, \({\gamma }_{{ISF}}\) values show a general downward trend with increasing atomic number of the TM (Figure S1). This trend is not mirrored in the case of unstable stacking faults (\({\gamma }_{{USF}}\), depicted by starts in Fig. 1), nor in the energy difference between \({\gamma }_{{USF}}\) and \({\gamma }_{{ISF}}\). Co- and Ni-containing structures display significantly deep \({\gamma }_{{ISF}}\) minima, in contrast to the shallower minima observed for the rest of TM systems. The presence of ISF’s denotes the possibility of forming P3-type stacking faults in all studied layered oxides. However, deeper \({\gamma }_{{ISF}}\) values, in principle, favor these transitions.

GSFs are shown for all studied phases with TM = Ti (a), Cr (b), Fe (c), Co (d), Mn (e), and Ni (f). The generalized stacking fault energy along the paths denoted by arrows are shown for rhombohedral O3 (g) and monoclinic O´3 (h) structures. The dashed arrows in (e, f) denote a second glide energy barrier (h) for the glide vector r perpendicular to the [0 1 0] direction (along the projection vector between the long JT distorted bond and the glide plane). The local sodium coordination of the non-faulted configuration and the intrinsic stacking fault are shown in (i), corresponding to an O3 (red square) and a P3 (black asterisk) structure, respectively. The unstable stacking faults are additionally shown (pink star), with a distorted square pyramid coordination of the Na-ions, and (blue circle) with an O1 stacking structure.

The γ-surfaces of O3-type compounds show a characteristic three-fold symmetry associated with the O3↔P3 transformation. In contrast, the monoclinic O’3 analogs display a single low-energy transition path, oriented perpendicular to the projection of the JT distorted bond onto the glide plane. This symmetry reduction suggests that lattice-invariant shears provoked by cycling are likely to have a diminishing effect in monoclinic O’3 compounds33.

In general, the results of our calculations are in good agreement with those reported by Kaufman et al.40, though some discrepancies arise due to differences in the methodology used to obtain the γ-surfaces. Specifically, our values for \({\gamma }_{{ISF}}\) and \({\gamma }_{{USF}}\) are slightly lower than those in the literature. This is likely because, in our simulations, all atoms in the slab are allowed to relax fully in the direction perpendicular to the slip plane, which is a condition not applied in previous works. This relaxation likely reduces the internal stress generated by shearing the crystal halves, resulting in flatter γ-surfaces and lower energies. Additionally, our calculations do not show an ISF with an O1 structure. This absence is attributed to our constrain that Na atoms in the slip plane were only allowed to relax perpendicularly, without in-plane movement, preventing the formation of the O1 configuration45.

While we emphasize the utility of calculating complete γ-surfaces to characterize plastic deformation behavior and the propensity for stacking fault formation—which largely affects the degradation mechanisms in NIBs—we also highlight the challenges involved in rigorously evaluating \(\gamma\)-surfaces for compounds containing mobile ions. Our study focuses on fully sodiated structures without vacancies (Va) at the Na sites and thus does not account for the broad range of possible Na/Va orderings. However, it is well known that Nax(TM)O2 layered oxides tend to form a rich variety of Na/Va orderings46. Some of these, such as the zig-zag row ordering in P3-Na0.5CoO2, become so energetically favorable that the local structure retains the zig-zag motif even as stoichiometry changes, accommodating these variations through the formation of antiphase boundaries47,48,49. These Na/Va orderings have been shown to largely affect glide barriers, as they alter the local coordination environments that Na ions experience at the transition state41. This may offer an atomistic explanation for the charge/discharge hysteresis observed in NIBs, where transitions between O↔P phases occur at different sodiation levels during cycling32,50. Similar considerations may apply to TM orderings in various cathode compositions51. Thus, a comprehensive statistical mechanics framework that incorporates both temperature effects and the configurational complexity of these systems is still desirable to advance the atomistic understanding of phase transformations in Nax(TM)O2 layered oxides. Such a framework could ultimately inform rational design strategies for controlling these transformations. In this context, the recent work by Natarajan et al.52, who developed a cluster expansion approach to model stacking fault energies by accounting for configurational disorder in multicomponent alloys, provides a promising direction. Extending this formalism to account for the effects discussed above in Nax(TM)O2 systems offers a fertile playground for further research.

Structure and stability of edge and screw dislocations

The previous section focused on obtaining γ-surfaces for fully discharged Na(TM)O2 layered oxides and discussed their relevance in the context of battery electrode operation. These surfaces were shown to be useful for characterizing the tendency to form stacking faults and for providing insight into O↔P phase transformations. However, caution must be exercised when interpreting γ-surfaces in a direct physical sense. In these materials, stacking sequence changes and plastic deformation do not occur via the rigid shearing of two crystal halves—an idealized mechanism that would require unrealistically high shear stresses. Instead, such processes are driven by the nucleation and motion of dislocations, as has been observed in other intercalation compounds for LIBs6,9,37,53,54. In this section, we analyze the structure of dislocation cores by examining the disregistry function, \({\delta }_{l}(\xi )\), where the index \(l=\mathrm{1,2,3}\) corresponds to components along the m, n, and ξ directions, respectively.

Figure 2 presents the disregistry and disregistry density of pure edge and screw dislocations, calculated using the SDVPN model based on the γ-surfaces introduced in the previous section and elastic constants (available in the Supporting Information). Across all studied Na(TM)O2 systems, dislocation cores show narrow average spreads of \(\sim 14{||}{\boldsymbol{b}}{||}( \sim 4{nm})\) for edge dislocations and \(\sim 8{||}{\boldsymbol{b}}{||}( \sim 2{nm})\) for screw dislocations. These values confirm the validity of the choice of cutoff distances typically used to evaluate elastic energies in explicit DFT models for dislocation dipoles in similar cathode materials for LIBs42. Interestingly, both edge and screw dislocations exhibit qualitatively different core structures depending on the TMs, as shown in Fig. 2c–f. For dislocations initialized with pure edge character, the system minimizes its energy by splitting into two partial dislocations in all cases, evident from the formation of two peaks in the disregistry density \({\rho }_{l}(\xi )\). In contrast, for pure screw dislocations, partial dislocation splitting occurs only in Ni- and Co-containing structures.

Disregistry paths for dislocations with edge (a) and screw (d) character, overlaid on a representative \(\gamma\)-surface for visual reference. The background \(\gamma\)-surface illustrates the stacking fault configurations explored locally by the dislocation core. Disregistry profiles \({\delta }_{l}(\xi )\) as a function of the coordinate \({\boldsymbol{\xi }}\) along the dislocation line for edge (b) and screw (e) dislocations across all studied TMs. Corresponding disregistry density \({\rho }_{l}(\xi )\) for edge (c) and screw (f) dislocations. The presence of two distinct peaks in \({\rho }_{l}(\xi )\) indicates that the dislocation splits into two partial dislocations, separated by a region corresponding to an ISF. The spacing between these peaks reflects the width of the stacking fault region. g Total dislocation energies as for edge (solid bars) and screw (hashed bars) dislocations. The difference between edge and screw dislocation is depicted in blue.

This behavior can be understood as a balance between two competing effects in the SDVPN model: the system’s drive to follow the minimum energy path for gliding on the \(\gamma\)-surface and the elastic energy penalty associated with increasing the dislocation core width. Partial dislocation separation is closely linked to stacking fault formation in O3-type layered oxides37. A dissociated dislocation consists of two partials whose individual Burgers vectors sum to that of the original dislocation, with the region between them representing a stacking fault. The width of this fault is determined by the ISF energy. This relationship is illustrated in the disregistry paths shown in Fig. 2a–c. For Ni- and Co-containing structures, the paths penetrate deeper into the γ-surface, reaching configurations associated with the ISF points (see Fig. 1). In contrast, other TM structures exhibit ISF configurations as very shallow minima, offering no energetic benefit to extend the disregistry path toward them.

In summary, our calculations show that even in the fully sodiated (non-stressed) state, O3-Na(TM)O2 layered oxides inherently accommodate both edge and screw dislocations. The atomic configurations in the regions between two partials resemble narrow (\(\sim 1-2{nm})\) P3 type structures. This phenomenon is especially pronounced for edge dislocations and for screw dislocations in Ni- and Co-containing compounds. We stress that these conclusions are specific to completely sodiated structures. The \(\gamma\)-surfaces and elastic constants are highly sensitive to Na/Va configurations, which can vary significantly during electrochemical cylcling52. Therefore, caution is warranted when extending these results to dynamic charge/discharge scenarios involving non-stoichiometric compositions.

Building on the previous discussion of dislocation structures and their connection to stacking faults and γ-surfaces, the SDVPN method also allows us to estimate the energy cost associated with dislocations, as defined in the previous section. Figure 2g shows the total energies for edge and screw dislocations across all studied Na(TM)O₂ systems. The Supplementary Information further decomposes these total energies into their respective contributions: misfit energy, core elastic energy, and long-range elastic energy. Overall, we see a consistent trend: screw dislocations are typically ~1.4–1.6 eV/Å more stable than their edge counterparts, with the exception of the monoclinic O’3-NaMnO2 structure, where the stability difference increases to ~2.5 eV/Å. Notably, dislocation energies for both O’3-type monoclinic structures—NaMnO2 and NaNiO2—are significantly lower than those of their rhombohedral O3 analogues, especially for screw dislocations.

This trend is consistent with previous work by Sadowski et al.42, who observed similar differences in excess dislocation energies for TM layered oxides in LIBs. They argued that lower shear moduli correlate with lower dislocation energies, citing the contrast between O3-LiCoO2 (92.5 GPa) and O’3-LiNiO2 (70.3 GPa). Their structural analysis further revealed that in O’3-LiNiO2, the JT active NiO6 octahedra can align collinearly to accommodate strain, thereby reducing dislocation energy relative to the stiffer, JT-inactive O3-LiCoO2. A similar correlation is observed in our results for Na(TM)O2 compounds. The Voigt-Reuss-Hill averaged shear moduli for the different TMs—78.7 GPa (Ti), 82.4 GPa (Cr), 61.4 GPa (Mn), 70.0 GPa (Fe), 90.9 GPa (Co), and 67.2 GPa(Ni)—track well with the long-range elastic energies computed for screw dislocations. For edge dislocations, an additional dependence on Poisson’s ratio \((\propto 1/1-\upsilon )\) is observed, with values of 0.24 (Ti), 0.23 (Cr), 0.22 (Mn), 0.24 (Fe), 0.23 (Co), and 0.23 (Ni), again correlating well with their respective long-range elastic energy contributions. The complete set of elastic constants and moduli is provided in the Supplementary Information.

The misfit energy component, on the other hand, is more directly influenced by the γ-surface. As discussed in the previous section (see Fig. 1c–f), JT-active phases such as those containing Mn and Ni tend to show lower energy barriers, which result in lower misfit energies. Structurally, the JT-distorted TM-O bonds also facilitate reaching ISF configurations with shorter lateral displacements across the glide plane. For example, in the rhombohedral structures, the Burgers vector required to reach the ISF point lies along the [1 2 0] direction, which corresponds to a longer translation than the [0 1 0] direction used in the monoclinic structures. This means that the disregistry path is shorter in the monoclinic phase, further reducing the elastic energy. Nonetheless, it is important to note that the elastic energy associated with the dislocation core—represented by the first term in the elastic energy expression, \({U}_{{elastic}}\)—results from a more convoluted interaction between the γ-surface and elastic fields, and its interpretation is not straightforward.

Estimation of Peierls stress

In the previous section, we examined the qualitatively distinct core structures of edge and screw dislocations in O3- and O’3-Na(TM)O2 layered oxides, as well as their associated dislocation energies and their dependence on elastic properties and \(\gamma\)-surfaces under zero-stress conditions. We now shift focus to another important aspect of dislocations: their mobility under applied mechanical stress.

The intrinsic resistance of the crystal lattice to dislocation movement is the most fundamental property governing dislocation mobility. This resistance is quantified by the Peierls stress \(({\tau }_{c})\), defined as the minimum shear stress required to initiate dislocation glide in the presence of lattice resistance. Accurate estimation of \({\tau }_{c}\) is essential, as it is closely linked to the critical resolved shear stresses (CRSS)—an experimentally measurable quantity in pure crystals55—which is directly related to the macroscopic yield strength of a material56. Despite its importance, accurate prediction of \({\tau }_{c}\) has proven challenging, particularly for continuum Peierls-Nabarro (PN)57,58 models. Kamimura et al. benchmarked \({\tau }_{c}\) predictions using PN models parameterized with DFT-calculated \(\gamma\)-surfaces and elastic properties across a variety of compounds with different crystal structures. They found that experiments and calculations correlated within an order of magnitude except for very soft crystals45. Later, Edagawa et al. recalculated \({\tau }_{c}\) using a discretized PN model—a simplified form of the SDVPN model introduced by Bulatov and Kaxiras43—which significantly improved agreement with experimental values. However, discrepancies greater than an order of magnitude persisted for soft crystals59.

To date, the evaluation of \({\tau }_{c}\) in energy materials—particularly cathode materials for batteries— has received limited attention in the literature. To the best of our knowledge, this work represents the first attempt to quantify the Peierls stress in Na(TM)O2 systems. The results presented in this section offer new insights into dislocation mobility in O3- and O’3-type structures and help establish a mechanistic link between lattice resistance and degradation phenomena in NIB cathodes.

The methodology used for \({\tau }_{c}\) calculation is detailed in the Methods section. Briefly, \({\tau }_{c}\) is obtained within the SDVPN framework by introducing an additional stress-dependent term, \({U}_{{stress}}\), to the total energy functional. This term accounts for the work done by an external shear stress on the dislocation.

Figures 3a, c show the position of the dislocation core as a function of the applied shear stress. In all of the studied systems, a characteristic step-like response is observed: the dislocation center remains stationary until a certain stress threshold is reached, beyond which it abruptly moves across the glide plane toward the domain edge. Further increases in applied shear stresses only slightly shift the core position. The value of \({\tau }_{c}\) (shown in Fig. 3b, d) is defined as the minimum shear stress at which this abrupt displacement occurs.

Our results reveal that O’3-type Ni and Mn phases exhibit significantly higher lattice resistances compared to their O3 counterparts, especially for dislocations with screw character. This is correlated with the anisotropic low-energy paths associated with the \(\gamma\)-surfaces (see Fig. 1f–h), which dictate the preferred slip pathways. As described in the Methods section, screw dislocations in monoclinic (C2/m) structures move along the \({\boldsymbol{\xi }}=[010]\) direction, parallel to their Burgers vector \(b[010]\). For the specific case of O’3 Ni- and Mn-containing phases, the \(\gamma\)-surfaces along this direction feature notably higher energy barriers (Fig. 1f), resulting in higher \({\tau }_{c}\) values. In contrast, the O3-type phases (Ti, Cr, Fe, and Co) exhibit relatively similar and lower \({\tau }_{c}\) values for screw dislocations, indicating more isotropic or favorable slip paths in their \(\gamma\)-surfaces. For edge dislocations, the \({\tau }_{c}\) trends diverge. Co, Fe and Mn show \({\tau }_{c}\) values comparable to those of their screw dislocations, whereas Ti, Cr, and Ni display significantly higher resistance to edge dislocation motion.

Despite these variations, all calculated \({\tau }_{c}\) values fall within the range of intercalation-induced stresses typically observed in similar cathode materials60,61,62. This confirms that dislocation glide on the (0 0 1) plane is energetically accessible under realistic battery operating conditions. On the contrary, rigid shearing of the TM–O planes, which is related to the ideal shear strength of the material and approximately proportional to the shear modulus63, would require stresses on the order of the shear moduli we computed (60–90 GPa), i.e., two to three orders of magnitude larger than the electrochemically induced stresses. Consequently, dislocation slip is expected to be an active deformation mechanism in Na(TM)O₂ cathodes, potentially contributing to microstructural evolution and degradation over cycling. However, we emphasize the need for future work that extends this analysis to other Na contents and explicitly accounts for all thermodynamically stable phases across the Na-stoichiometry range, to further elucidate O3↔P3 phase transformations.

Discussion

The work presented herein represents an important first step toward a first-principles description of dislocations in materials for next-generation NIBs. We investigated the \(\gamma\)-surfaces of completely discharged O3- and O’3-type Na(TM)O2 layered oxides, with TM = Ti, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, and Ni. These surfaces generally show shallow \({\gamma }_{{ISF}}\) values, except for Co and Ni, which exhibit deeper minima in relation to the \({\gamma }_{{USF}}\). Therefore, while the formation of a metastable prismatic P3 coordination is allowed in all cases, it is facilitated for Co and Ni.

Importantly, no local minima are observed for the O1 configuration across these systems. The absence of such minima stems from the necessity of accommodating vertical atomic relaxations and Na-ion mobility during shearing between the crystal halves. Prior studies highlight that the formation of O1 phases is governed by the interplanar distances between O atoms within Na-O and TM-O octahedra. These O1 phases are considered detrimental compared to the more favorable, smooth, and highly reversible O3\(\leftrightarrow\)P3 transformations30.

Evaluating \(\gamma\)-surfaces thus provides a direct and valuable metric for predicting the tendency of layered materials to undergo stacking sequence transformations. However, a complete statistical mechanics framework—one that incorporates temperature effects and configurational Na/Va ordering—remains desirable52. This is especially relevant for intercalation-type layered oxides, where the extend of Na intercalation correlates strongly with the flatness of the \(\gamma\)-surface41,42. Furthermore, specific Na/Va orderings, such as the “zig-zag” motif47, have been shown to promote highly unstable stacking fault configurations41, which could give further insights into the hysteresis observed for these materials regarding stacking sequence changes, where barriers in the \(\gamma\)-surface for a O3\(\to\)P3 transformation could be different from the reversed P3\(\to\)O3 transformation given that a different Na/Va ordering is stabilized.

However, direct physical interpretation of \(\gamma\)-surfaces limited, as changes in stacking sequence arise not from rigid crystal shearing, but from dislocation nucleation and motion, which drive plastic deformation. In this work, the SDVPN model is used to describe the structure and stability of pure edge and screw dislocations by analyzing the disregistry function \({\boldsymbol{\delta }}(\xi )\) along the direction of dislocation motion. Our simulations reveal narrow dislocation core structures, consistent with the intrinsically hard nature of Na(TM)O2 layered oxides. Edge dislocations are observed to split into partial dislocations, where the disregistry path explores configurations close to the \({\gamma }_{{ISF}}\) points—corresponding to P3-type stacking. This behavior is especially pronounced in Co- and Ni-containing phases, where deeper ISF minima are present. In contrast, screw dislocations show more compact cores and do not split into partials, again with the exception of Co- and Ni-containing phases.

Overall, screw dislocations have lower energies than the edge dislocations, with the lowest energies observed in phases containing JT-active Ni and Mn species. Additionally, Peierls stress values (\({\tau }_{c}\)) are predicted by solving the SDVPN disregistry under applied shear stresses. \({\tau }_{c}\) values range from 4.8 to 20.9 MPa for edge dislocations and from 2.4 to 14.1 MPa for screw dislocations—well within the ion-intercalation-induced stress range predicted for similar cathode materials used in LIBs60,61,62.

Figure 4 illustrates the proposed dislocation-driven mechanism for the O3\(\to\)P3 phase transformation, by following the relative translation of O atoms across the glide plane for pure screw dislocations in O3-NaCoO2. To simulate the widening of stacking fault regions upon desodiation, we assume a linear dependence of the \({\gamma }_{{ISF}}\) on the intercalated Na concentration, while neglecting stress effects. Additionally, we prescribe the shape of the compositional gradients that form in the particles upon desodiation (the full details are found in the Supporting Information). While these assumptions may not strictly hold in real systems, they provide a physically sensible picture that helps build intuition regarding the atomic structure of the dislocation core and how the O3\(\to\)P3 phase transformation may proceed. At the beginning of charge, in the fully sodiated state, either pre-existing or newly nucleated dislocations can dissociate into partial dislocations, forming narrow regions with P3-type stacking. As charging progresses and Na is extracted, the local \(\gamma\)-surface evolves, further stabilizing the ISF configuration. This leads to the broadening of P3-staked regions along the dislocation line. With further desodiation, the P3 configuration transitions from a metastable state to a new global minimum, weakening the \({\gamma }_{{ISF}}\)-derived restoring force that previously kept the partial dislocations bound. As a result, partial dislocations move further apart41. The combination of the P3-like distorted lattice (gray areas in Fig. 4) and compositional gradients within the layer favor temperature activated Na-ion jumps from octahedral to prismatic configurations. These ions then diffuse further into the stabilized P3 regions, promoting the progression of the O3\(\to\)P3 phase boundary along the direction of dislocation motion. Upon further charging, the evolving \(\gamma\)-surface would develop deeper local minima associated with other stacking orderings (e.g., O1-type configurations). Once these configurations become thermodynamically more favorable than the P3 phase, a similar transformation mechanism ensues, with dislocations again serving as nucleation pathways and mediators of the phase transition.

Circles represent a top view of the oxygen atoms in the transition metal layer at both sides of the glide plane. Atoms at the near side of the glide plane are marked in purple to represent O3-type atomic arrangements, dark grey to indicate the distorted in-between configurations where the dislocation partials are located (solid lines for visual reference), and yellow to represent P3-type atomic arrangements. The smaller light-grey atoms depict the oxygen lattice at the back side of the glide plane. Dashed red line marks the position of the dislocation line.

Additionally, we have shown that the charging and discharging process likely induces chemical stresses above \({\tau }_{c}\)61, which further drive dislocation motion, including the movement of leading and trailing partial dislocations. In our SDVPN model, we limited the analysis to shear stresses parallel to the Burgers vector of a perfect, infinite dislocation. However, stress fields in polycrystalline cathode active materials may have different directional components64. Indeed, the Peach-Koehler forces acting on dislocations are governed by both Schmid and Escaig stresses—the former promoting dislocation glide, while the latter influences the separation of partial dislocations. This can lead to indefinite widening of the stacking fault under certain conditions65,66,67,68,69, and may promote the formation of other extended defects such as twins.

Atomistic modelling studies of dislocations in battery materials remain scarce in literature. Yet the nucleation, movement, and accumulation of dislocations at grain boundaries are directly linked to active material degradation mechanisms and, by extension, battery lifetime. For example, dislocation-mediated formation of extrinsic stacking faults has been identified as the main responsible for detrimental intragranular cracking in layered cathode materials7,34,70. The pilling up of dislocations emitted from the bulk to the active material grain boundaries can also lead to the accumulation of shear stresses that initiate microcracks71, which in turn accelerate fatigue and promote the irreversible formation of undesired new phases35. Native lattice strains leads to premature nucleation of dislocations and formation of stacking faults causing a cascade of phase transformations that compromise structural integrity through particle cracking and fragmentation32. Additionally, it has been shown that the relative ratio of interplanar distance between the oxygen sublattices in the Na and TM layers is a key structural parameter detrimental to cycling stability30. When this ratio is carefully engineered, the formation of the O1 phase at early charging stages phase is completely suppressed, and smooth, reversible O3\(\leftrightarrow\)P3 transformations are maintained, ensuring stable and long-term cycling performance. These findings evince the sensitivity of interlayer distances in determining the relative stability of O- and P-type phases in Na-based layered TM oxides72, which, in turn, directly influence the behavior of the dislocations and the \(\gamma\)-surfaces with which they interact.

Thus, we put forward that to advance atomistic understanding of dislocations in battery materials, future studies should integrate SDVPN models with statistical mechanical descriptions of \(\gamma\)-surfaces accounting for temperature and Na/Va configuration space. At present, our analysis is limited to fully sodiated structures in which the O3 phase is thermodynamically stable. We interpret dislocation structure, stability, and stress response using fixed \(\gamma\)-surfaces, and we can provide insights on the O3\(\to\)P3 phase transformation only during charge. The reverse transformation on discharge (P3\(\to\)O3) remains inaccessible because the relevant \(\gamma\)-surfaces—set by specific Na/Va orderings in P3—are not yet known. Additionally, advancing in the development of fully atomistic simulations is essential for capturing complex phenomena such as kink-pair nucleation and motion, which require very large simulation boxes42—currently beyond the capabilities of DFT methods. In this context, machine learned interatomic potentials for molecular dynamics simulations offer a promising path forward for exploring these mechanisms at realistic length and time scales73,74.

Methods

Density Functional Theory

Spin-polarized DFT calculations were performed with the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)75,76 using the projector augmented-wave (PAW) method77,78. We explicitly treated the Na (2p63s1), Ti (4s13d3), Cr (3p64s13d5), Mn (3p64s13d6), Fe (3p64s13d7), Co (3p64s13d8), Ni (3p64s13d9), and O (2s22p4) electrons as valence electrons. We used the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE)79 exchange correlation functional for all our simulations (see the Supporting Information for a discussion on the effect of the exchange-correlation functional). Spin polarization was fixed in a ferromagnetic configuration, and the magnetic moments of TM centers were initialized at high-spin for Ti3+, Cr3+, Fe3+, and Mn3+, while a low-spin configuration was used for Co3+ and Ni3+. The plane-wave energy cutoff was set to 620 eV, and a Γ-centered k-point mesh of 12 × 12 × 1 was employed. The electronic self-consistent calculations were performed with a energy converge criterion of 10−6 eV.

The GSF surface is a periodic two-dimensional function dependent on the glide vector \({\boldsymbol{r}}\) which is parallel to a slip plane that cuts two crystal halves. The energy per unit area associated to this translation is called the GSF energy \(\gamma ({\boldsymbol{r}})\). In this work, orthogonal and centrosymmetric slabs were built to calculate \(\gamma ({\boldsymbol{r}})\) 45,80,81,82 using the functionalities provided within Atomic Simulation Environment (ASE)83 and PYMATGEN84 libraries, which resulted in non-stochiometric slabs, preventing dipole moments from affecting the slip-plane. Additionally, at least three parallel TM layers were included at both sides of the (0 0 1) slip plane, which was located at the middle of the slab between the Na and O sublattices. This ensured that surface relaxation effects were minimized in the center of the slab. A vacuum separation of 20 \(\mathring{\rm A}\) in the direction perpendicular to the (0 0 1) slip plane was additionally introduced, to avoid interaction between periodic slab images. Figure 5 depicts the unit cells and slabs used in this study.

During structural relaxation, atomic positions were allowed to relax only along the direction perpendicular to the slab surface (c-axis), while movements along the in-plane a and b directions were constrained and the bottom-most O layer was completely fixed. The residual force threshold was set to 0.02 eV/\(\mathring{\rm A}\). A grid of 10× 10 glide vectors \(\{{\boldsymbol{r}}{\boldsymbol{\}}}\) was constructed spanning fractions of the a and b cell parameters, resulting in a hundred geometry optimizations per Na(TM)O2 oxide, leading to the computation of a total of 600 geometrical relaxations. The GSF energy for each glide vector was then calculated as:

where \(A\) is the surface area of the interface. This methodology slightly differs from that introduced by Kaufman et al.40, where a supercell is used instead of a slab, and all atomic positions are kept fixed during relaxation except for the mobile ions within the fault plane, which are fully relaxed.

Elastic constants were calculated using the energy-strain method as implemented in the VASPKIT package85. Due to the stricter convergence requirements for these calculations, the plane-wave energy cutoff was increased to 720 eV. The electronic self-consistent field convergence criterion was tightened to 10−9 eV, and the residual force threshold for geometry optimization was set to 10−4 eV/\(\mathring{\rm A}\). Γ-centered k-point grids of 12 × 12× 4 and 10 × 14 × 10 were employed for the rhombohedral (\({\rm{R}}\bar{3}{\rm{m}}\)) and monoclinic (\({\rm{C}}2/{\rm{m}}\)) systems, respectively. The PBE + U correction was applied to better capture electron localization in strongly correlated 3 d orbitals, which significantly affects the calculation of elastic constants. The applied U corrections were: 0.0 eV for Ti, 3.5 eV for Cr, 3.9 eV for Mn, 4.0 eV for Fe, 3.4 eV for Co, and 6.0 eV for Ni46,84.

Semi-Discrete Variational Peierls-Nabarro model

The SDVPN model43,44 was used to predict the core structure of dislocations based on the GSF energies and elastic constants, both of which can be readily obtain from DFT simulations, as described in the previous section. The approach expresses the dislocation energy as a functional of the disregistry \({\boldsymbol{\delta }}(\xi )\), and determines the dislocation structure by variationally minimizing this functional. Here, \(\xi\) represents the coordinate along the direction parallel to the slip plane \((001)\) and perpendicular to the dislocation line, while the disregistry \({\boldsymbol{\delta }}(\xi )\) is defined as the relative displacement between atoms on either side of the dislocation plane.

Compared to the continuum Peierls-Nabarro method57,58, the SDVPN model introduces a discretization parameter, \(\Delta \xi\), which defines the set of regularly spaced points \(\{{\xi }_{i}\}\) at which the disregistry contributions to the dislocation energy \({U}_{{disl}}\)[\({\boldsymbol{\delta }}({\xi }_{i})]\) are evaluated. The disregistry is assumed constant between any other point not included in \(\{{\xi }_{i}\}\). Typically, \(\Delta \xi\) is chosen to match the spacing of atomic columns along the \(\xi\)-direction, giving the model a level of discreteness that reflects the atomic structure of the crystal. The selection of \(\Delta \xi\) has a significant impact on the predicted values of dislocation-related properties, such as the critical shear stresses (Peierls stresses, \({\tau }_{c}\)) required to move dislocations from the crystal interior to grain-boundary edges86,87.

The dislocation system is represented by three vectors: Burgers vector \({\boldsymbol{b}}\), the slip-plane normal \({\boldsymbol{n}}\), and the dislocation line direction \({\boldsymbol{m}}\). These define a local orthogonal coordinate system with \({\boldsymbol{\xi }}={\boldsymbol{m}}\times {\boldsymbol{n}}\), the direction along which the disregistry \({\boldsymbol{\delta }}(\xi )\) is evaluated which is also the direction of dislocation motion. The components of the disregistry are expressed in this basis. The dislocation character (edge, screw, or mixed) is determined by the angle between b and m; edge dislocations have b ⊥ m, while screw dislocations have b \({\boldsymbol{||}}\) m.

In our simulations, the dislocation reference frames were defined as follows. For rhombohedral (\({\rm{R}}\bar{3}{\rm{m}}\)) structures, we used \({\boldsymbol{b}}=a[100]\) (along the cell axis a) and \({\boldsymbol{m}}=[\bar{1}\,\bar{2}\,0]\) for edge dislocation, and \({\boldsymbol{m}}=[100]\) for screw dislocations. For monoclinic (\({\rm{C}}2/{\rm{m}}\)) structures, we set \({\boldsymbol{b}}=b[010]\) (along cell axis b) and \({\boldsymbol{m}}=[100]\) for edge dislocation, and \({\boldsymbol{m}}=[010]\) for screw dislocations. In all systems studied, the slip plane normal is defined as \({\boldsymbol{n}}=(001)\). Given these vectors, \(\Delta \xi\) was selected as \({||}{\boldsymbol{b}}{||}/2\)(\({||}{\boldsymbol{b}}{||}/2\sqrt{3})\) for edge (screw) dislocations in rhombohedral structures. In monoclinic cases, \(\Delta \xi\) is properly defined as \({||}{\boldsymbol{b}}{||}/2\) for edge dislocations. However, \(\Delta \xi\) for screw dislocations has certain arbitrariness given that several options can be selected for the spacing between crystal sublattices along the \({\boldsymbol{\xi }}\) direction55 due to the long-axis distortions induced by the JT distortion, for which we set \(\Delta \xi =a/6\) as an approximation. Lastly, the dislocation energy functional we used in this work is separated into the following contributions:

where \({U}_{{elastic}}{\boldsymbol{[}}{\boldsymbol{\delta }}({\xi }_{i})]\) includes both short-range interactions related to disregistry and long-range contributions from the dislocation-induced strain field:

where \({\rho }_{l}({\xi }_{i})={(\delta }_{l}({\xi }_{i})-{\delta }_{l}({\xi }_{i-1}))/\varDelta \xi\), \({\chi }_{{ij}}=\frac{3}{2}{\varDelta \xi }^{2}+{\psi }_{i-1,j-1}+{\psi }_{{ij}}-{\psi }_{i,j-1}-{\psi }_{j,i-1}\), and \({\psi }_{{ij}}=\frac{1}{2}{(i-j)}^{2}{\varDelta \xi }^{2}\mathrm{ln}(\left|i-j\right|\varDelta \xi )\). Here, \({K}_{{lm}}\) is the anisotropic tensor, computed using the Stroh88 method to solve Eshelby’s elastic model for straight dislocations89. Additionally, \({U}_{{misfit}}{\boldsymbol{[}}{\boldsymbol{\delta }}({\xi }_{i})]\) is the misfit energy that accounts for the local atomic distortions across the dislocation, captured through the GSF energy \(\gamma\):

Lastly, this study includes the energy contributions due to externally applied stress, through the stress energy \({U}_{{stress}}{\boldsymbol{[}}{\boldsymbol{\delta }}({\xi }_{i})]\):

where \({\tau }_{l}\) is the stress that results in forces along direction \({\boldsymbol{\xi }}\). In these formulas the additional indices \(l\) and \(m\) denote the vector components of the disregistry for the dislocation coordinate system \({\boldsymbol{m}}\), \({\boldsymbol{n}}\), and \({\boldsymbol{\xi }}\), that also serve as tensor notation to denote the implicit summation over repeated indices.

The initial disregistry was chosen as an arc-tangent function, with its half-width varied during the energy minimization to ensure convergence. Boundary conditions were enforced such that \({\boldsymbol{\delta }}(0)={\boldsymbol{0}}\) and \({\boldsymbol{\delta }}({\xi }_{N})={\boldsymbol{b}}\), and these constraints were maintained throughout the minimization procedure.

All the abovementioned equations were solved using the built-in functionalities implemented in the atomman library (https://github.com/usnistgov/atomman). The zero stress solutions of the dislocation spread were obtained using Powell’s minimization method90. The stressed dislocation solutions were calculated by taking the non-stress solution as the initial guess and iteratively solving the SDVPN model by incrementally ramping the stress and using the previous converged solution as the initial guess for the next stress condition. The Broyden-Flecher-Goldfarb-Shanno (BFGS) optimization algorithm was used to resolve the stressed disregistry91. Lastly, all cases were simulated in a 400 \(\mathring{\rm A}\) domain ensuring that the fixed boundary points would not interact with the dislocation core.

Data availability

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

References

Kaplan, W. D. The mechanism of crystal deformation: Microscopy provides an atomistic view of how crystalline materials deform. Science (1979) 349, 1059–1060 (2015).

Hasebe, T. Field Theory of Multiscale Plasticity. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2024).

Xiong, Y. et al. Interactions between irradiation-induced defects and dislocations in concentrated solid solution alloys. J. Nucl. Mater. 597, 155144 (2024).

Wang, J. et al. Corrosion behavior of nickel-based superalloys in thermal storage medium of molten eutectic NaCl-MgCl2 in atmosphere. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 164, 146–155 (2017).

Wang, L. et al. Dislocations in Crystalline Silicon Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Sustainability Res. 5, 2300240 (2024).

Singer, A. et al. Nucleation of dislocations and their dynamics in layered oxide cathode materials during battery charging. Nat. Energy 3, 641–647 (2018).

Yan, P. et al. Intragranular cracking as a critical barrier for high-voltage usage of layer-structured cathode for lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 8, 1–9 (2017).

Nakayama, K., Ishikawa, R., Kobayashi, S., Shibata, N. & Ikuhara, Y. Dislocation and oxygen-release driven delithiation in Li2MnO3. Nat. Commun. 11, 4452 (2020).

Li, Q. et al. Dynamic imaging of crystalline defects in lithium-manganese oxide electrodes during electrochemical activation to high voltage. Nat. Commun. 10, 1–7 (2019).

Xu, Z. et al. Charging Reactions Promoted by Geometrically Necessary Dislocations in Battery Materials Revealed by In Situ Single-Particle Synchrotron Measurements. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003417 (2020).

Dhiman, P. & Huang, H. Y. S. Dislocation based stresses during electrochemical cycling and phase transformation in lithium-ion batteries. Comput Mater. Sci. 171, 109275 (2020).

Chen, H., Kim, S. & Huang, H. Y. S. Exploration of the dislocation-electrochemistry relation in LiFePO4 cathode materials. Acta Mater. 237, 118158 (2022).

Zeng, L. Techno-economic analysis for lithium-ion battery manufacturing and recycling. Nat. Rev. Clean. Technol. 1, 114 (2025).

Bruno, M. & Fiore, S. Review of lithium-ion batteries’ supply-chain in Europe: Material flow analysis and environmental assessment. J. Environ. Manag. 358, 120758 (2024).

Hwang, J.-Y., Myung, S.-T. & Sun, Y.-K. Sodium-ion batteries: present and future. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 3529–3614 (2017).

Yao, A., Benson, S. M. & Chueh, W. C. Critically assessing sodium-ion technology roadmaps and scenarios for techno-economic competitiveness against lithium-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 10, 404–416 (2025).

Duffner, F. et al. Post-lithium-ion battery cell production and its compatibility with lithium-ion cell production infrastructure. Nat. Energy 6, 123–134 (2021).

Marangon, V. et al. Cell design and chemistry of commercial sodium-ion battery cells. J. Power Sources 634, 236496 (2025).

Rehm, M. et al. Comparing the electrical performance of commercial sodium-ion and lithium-iron-phosphate batteries. J. Power Sources 633, 236290 (2025).

Nguyen, L. H. B. et al. First 18650-format Na-ion cells aging investigation: A degradation mechanism study. J. Power Sources 529, 231253 (2022).

Qian, Y. et al. Elucidating the self-discharge failure mechanism of 32140 cylindrical sodium-ion battery with O3-NaNi1/3Mn1/3Fe1/3O2 cathode. J. Power Sources 649, 237474 (2025).

Schütte, M. et al. First full cell parameterization of a commercial layered oxide/hard carbon sodium-ion 18650 battery cell for a physico-chemical model. J. Energy Storage 107, 114931 (2025).

Temprano, I. et al. Advanced methods for characterizing battery interfaces: Towards a comprehensive understanding of interfacial evolution in modern batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 73, 103794 (2024).

Park, S. et al. Obtaining V2(PO4)3 by sodium extraction from single-phase NaxV2(PO4)3 (1 < x < 3) positive electrode materials. Nat. Mater. 24, 234–242 (2024).

Zuo, W. et al. Layered Oxide Cathodes for Sodium-Ion Batteries: Storage Mechanism, Electrochemistry, and Techno-economics. Acc. Chem. Res 56, 284–296 (2023).

Delmas, C., Fouassier, C. & Hagenmuller, P. Structural classification and properties of the layered oxides. Phys. B+C. 99, 81–85 (1980).

Delmas, C. Sodium and Sodium-Ion Batteries: 50 Years of Research. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1703137 (2018).

Usiskin, R. et al. Fundamentals, status and promise of sodium-based batteries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 1020–1035 (2021).

Gonzalo, E., Zarrabeitia, M., Drewett, N. E., López del Amo, J. M. & Rojo, T. Sodium manganese-rich layered oxides: Potential candidates as positive electrode for Sodium-ion batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 34, 682–707 (2021).

Li, M. et al. Unravelling the structure-stability interplay of O3-type layered sodium cathode materials via precision spacing engineering. Nat. Commun. 16, 2010 (2025).

Yang, Y. et al. Suppressed O3–P3 phase transition of Cu/Fe/Mn-based layered oxides as cathode materials for high performance sodium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 616, 235082 (2024).

Xu, G. L. et al. Native lattice strain induced structural earthquake in sodium layered oxide cathodes. Nat. Commun. 13, 1–12 (2022).

Radin, M. D., Alvarado, J., Meng, Y. S. & Van der Ven, A. Role of Crystal Symmetry in the Reversibility of Stacking-Sequence Changes in Layered Intercalation Electrodes. Nano Lett. 17, 7789–7795 (2017).

Liang, X. et al. High-energy and long-life O3-type layered cathode material for sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 16, 1–15 (2025).

Liu, C., Roters, F. & Raabe, D. Role of grain-level chemo-mechanics in composite cathode degradation of solid-state lithium batteries. Nat. Commun. 15, 1–18 (2024).

Sun, Y., Guo, S. & Zhou, H. Adverse effects of interlayer-gliding in layered transition-metal oxides on electrochemical sodium-ion storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 825–840 (2019).

Gabrisch, H., Yazami, R. & Fultz, B. The Character of Dislocations in LiCoO2. Electrochem. Solid-State Lett. 5, A111 (2002).

Bi, Y. et al. Reversible planar gliding and microcracking in a single-crystalline Ni-rich cathode. Science (1979) 370, 1313–1317 (2020).

Kumakura, S. et al. Synthesis and Electrochemistry of Stacking Fault-Free β-NaMnO2. Adv. Mater. 37, 2507011 (2025).

Kaufman, J. L., Vinckevičiūtė, J., Krishna Kolli, S., Gabriel Goiri, J. & Van Der Ven, A. Understanding intercalation compounds for sodium-ion batteries and beyond. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 377, 20190020 (2019).

Arcelus, O. & Carrasco, J. Atomistic Insight into Glide-Driven Phase Transformations in Layered Oxides for Sodium-Ion Batteries: A Case Study on NaxVO2. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 11, 12562–12569 (2019).

Sadowski, M., Koch, L., Albe, K. & Sicolo, S. Planar Gliding and Vacancy Condensation: The Role of Dislocations in the Chemomechanical Degradation of Layered Transition-Metal Oxides. Chem. Mater. 35, 584–594 (2023).

Bulatov, V. V. & Kaxiras, E. Semidiscrete variational peierls framework for dislocation core properties. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 4221–4224 (1997).

Lu, G., Kioussis, N. & Bulatov, V. V. Generalized-stacking-fault energy surface and dislocation properties of aluminum. Phys. Rev. B 62, 3099–3108 (2000).

Kamimura, Y. et al. Peierls stresses estimated via the Peierls-Nabarro model using ab-initio γ-surface and their comparison with experiments. Acta Mater. 148, 355–362 (2018).

Toumar, A. J., Ong, S. P., Richards, W. D., Dacek, S. & Ceder, G. Vacancy Ordering in O3 -Type Layered Metal Oxide Sodium-Ion Battery Cathodes. Phys. Rev. Appl 4, 1–9 (2015).

Kaufman, J. L. & Van der Ven, A. NaxCoO2 phase stability and hierarchical orderings in the O3/P3 structure family. Phys. Rev. Mater. 3, 15402 (2019).

Kaufman, J. L. & Van der Ven, A. Cation Diffusion Facilitated by Antiphase Boundaries in Layered Intercalation Compounds. Chem. Mater. 34, 1889–1896 (2022).

Kaufman, J. L. & Van der Ven, A. Antiphase boundary migration as a diffusion mechanism in a P3 sodium layered oxide. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 55401 (2021).

Didier, C. et al. Thermally and Electrochemically Driven Topotactical Transformations in Sodium Layered Oxides NaxVO2. Chem. Mater. 28, 1462–1471 (2016).

Pfeiffer, L. F. et al. From structure to electrochemistry: the influence of transition metal ordering on Na+/vacancy orderings in P2-type NaxMO2 cathode materials for sodium-ion batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 13, 540–560 (2024).

Natarajan, A. R. & Van der Ven, A. Linking electronic structure calculations to generalized stacking fault energies in multicomponent alloys. NPJ Comput Mater. 6, 80 (2020).

Ulvestad, A. et al. Topological defect dynamics in operando battery nanoparticles. Science (1979) 348, 1344–1347 (2015).

Serban, D. et al. Imaging in-operando LiCoO2 nanocrystallites with Bragg coherent X-ray diffraction. Commun. Chem. 7, 243 (2024).

Kamimura, Y., Edagawa, K. & Takeuchi, S. Experimental evaluation of the Peierls stresses in a variety of crystals and their relation to the crystal structure. Acta Mater. 61, 294–309 (2013).

Siu, K. W. & Ngan, A. H. W. Relation Between Yield Stress and Peierls Stress. Phys. Status Solidi B 256, 1900107 (2019).

Peierls, R. The size of a dislocation. Proc. Phys. Soc. 52, 34–37 (1940).

Nabarro, F. R. N. Dislocations in a simple cubic lattice. Proc. Phys. Soc. 59, 256–272 (1947).

Edagawa, K., Kamimura, Y., Iskandarov, A. M., Umeno, Y. & Takeuchi, S. Peierls stresses estimated by a discretized Peierls–Nabarro model for a variety of crystals. Materialia (Oxf.) 5, 100218 (2019).

Clerici, D. Diffusion-induced stress amplification in phase-transition materials for electrodes of lithium-ion batteries. Int J. Mech. Sci. 281, 109541 (2024).

Pistorio, F., Clerici, D., Mocera, F. & Somà, A. Coupled electrochemical–mechanical model for fracture analysis in active materials of lithium ion batteries. J. Power Sources 580, 233378 (2023).

Ai, W., Kraft, L., Sturm, J., Jossen, A. & Wu, B. Electrochemical Thermal-Mechanical Modelling of Stress Inhomogeneity in Lithium-Ion Pouch Cells. J. Electrochem Soc. 167, 013512 (2020).

Phillips, R. Crystals, Defects and Microstructures: Modeling Across Scales. (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2001).

Parks, H. C. W. et al. Direct observations of electrochemically induced intergranular cracking in polycrystalline NMC811 particles. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 21322–21332 (2023).

Unocic, R. R. et al. Dislocation decorrelation and relationship to deformation microtwins during creep of a γ′ precipitate strengthened Ni-based superalloy. Acta Mater. 59, 7325–7339 (2011).

León-Cázares, F. D., Monni, F. & Rae, C. M. F. Stress orientation dependence for the propagation of stacking faults and superlattice stacking faults in nickel-based superalloys. Acta Mater. 199, 209–224 (2020).

León-Cázares, F. D. & Rae, C. M. F. A stress orientation analysis framework for dislocation glide in face-centred cubic metals. Cryst. (Basel) 10, 445 (2020).

McCabe, R. J., Beyerlein, I. J., Carpenter, J. S. & Mara, N. A. The critical role of grain orientation and applied stress in nanoscale twinning. Nat. Commun. 5, 1–7 (2014).

Byun, T. S. On the stress dependence of partial dislocation separation and deformation microstructure in austenitic stainless steels. Acta Mater. 51, 3063–3071 (2003).

Morzy, J. K. et al. Origins and Importance of Intragranular Cracking in Layered Lithium Transition Metal Oxide Cathodes. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 7, 3945–3956 (2024).

Sharifi-Asl, S. et al. Revealing Grain-Boundary-Induced Degradation Mechanisms in Li-Rich Cathode Materials. Nano Lett. 20, 1208–1217 (2020).

Katcho, N. A. et al. Origins of Bistability and Na Ion Mobility Difference in P2- and O3-Na2/3Fe2/3Mn1/3O2Cathode Polymorphs. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1–9 (2017).

Maresca, F., Dragoni, D., Csányi, G., Marzari, N. & Curtin, W. A. Screw dislocation structure and mobility in body centered cubic Fe predicted by a Gaussian Approximation Potential. NPJ Comput Mater. 4, 69 (2018).

Carrasco, J. A theoretical perspective on solid-state ionic interfaces. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 382, 20230313 (2024).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular-dynamics simulation of the liquid-metal–amorphous-semiconductor transition in germanium. Phys. Rev. B 49, 14251–14269 (1994).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Wu, X. Z., Wang, R., Wang, S. F. & Wei, Q. Y. Ab initio calculations of generalized-stacking-fault energy surfaces and surface energies for FCC metals. Appl Surf. Sci. 256, 6345–6349 (2010).

Yang, B. et al. Generalized stacking fault energies and ideal strengths of MC systems (M = Ti, Zr, Hf) doped with Si/Al using first principles calculations. J. Alloy. Compd. 739, 431–438 (2018).

Su, Y., Xu, S. & Beyerlein, I. J. Density functional theory calculations of generalized stacking fault energy surfaces for eight face-centered cubic transition metals. J. Appl Phys. 126, 105112 (2019).

Hjorth Larsen, A. et al. The atomic simulation environment—a Python library for working with atoms. J. Phys: Condens Matter 29, 273002 (2017).

Jain, A. et al. A high-throughput infrastructure for density functional theory calculations. Comput Mater. Sci. 50, 2295–2310 (2011).

Wang, V., Xu, N., Liu, J. C., Tang, G. & Geng, W. T. VASPKIT: A user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Comput Phys. Commun. 267, 108033 (2021).

Shen, Y. & Cheng, X. Dislocation movement over the Peierls barrier in the semi-discrete variational Peierls framework. Scr. Mater. 61, 457–460 (2009).

Zhang, X. C., Cao, S., Yang, R. & Hu, Q. M. Drastic oscillation of peierls stress from peierls-nabarro model calculation and its remedy. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 23, 5502–5519 (2023).

Stroh, A. N. Steady State Problems in Anisotropic Elasticity. J. Math. Phys. 41, 77–103 (1962).

Eshelby, J. D., Read, W. T. & Shockley, W. Anisotropic elasticity with applications to dislocation theory. Acta Metall. 1, 251–259 (1953).

Powell, M. J. D. An efficient method for finding the minimum of a function of several variables without calculating derivatives. Comput J. 7, 155–162 (1964).

Nocedal, J. & Wright, S. J. Numerical Optimization. in 529–562 (Springer New York, New York, NY, 2006).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the financial support received from ELKARTEK Program (grant KK-2024/00062) of the Basque Government and the IKUR Strategy under the collaboration agreement between Ikerbasque Foundation and CIC Energigune on behalf of the Department of Science, Universities and Innovation of the Basque Government. The authors also acknowledge the technical support provided by the Barcelona Supercomputing Center and the computer resources from CETACIEMAT (QHS-2024-2-0002 and QHS-2024-3-0001), SGI/IZO-SGIker UPV/EHU, and i2BASQUE academic network. The authors thank Dr. Lucas Hale, original author of the atomman library, for fruitful discussions and useful tips regarding the application of the SDVPN model.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.A. designed the research and performed the simulations. O.A. and J.C. discussed, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Arcelus, O., Carrasco, J. First-principles computation of dislocation structures and stress-driven phase transformations in layered oxides for Na-ion batteries. npj Comput Mater 12, 96 (2026). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-026-01965-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41524-026-01965-7